YEVHEN SVERSTIUK on Ivan POKROVSKY

(From an interview with I. Pokrovsky, July 25, 2002).

I was always interested in the phenomenon of Pokrovsky. After all, there were many people who were imprisoned with him and were serving out the same sentences, and it would hardly have occurred to me to travel to see them or meet with them. They are their own people, and each has their own fate. But Ivan’s fate is somehow close to the hearts of many and always has been, which is very interesting. He is an unassuming man, a taciturn man, tremendously patient and modest. But he gets noticed—the authorities notice him, never forgetting about him; the zeks notice him, and he is present in all the important moments of camp life because he carries within him this spark of resistance, a spark that is never extinguished. And although I knew him for only a couple of years, from the summer of 1973 to 1974—not even a couple of years—he remains in my memory as someone strong, stocky, guileless, genuine, and faithful to the end. A man you can rely on, a man who will do well whatever he takes on. And it became a little clearer to me who he was when he said that he came from a line of priests on both his father’s and his mother’s side. That clarified things for me. Then, when he said that he had finished, or almost finished, gymnasium. That, of course, mattered a great deal. And the fact that he never found anything in his case worth telling, but simply carried with him the fate of his motherland—it was repressed, and he was repressed with it. It lived an unremarkable and unpretentious life—and he lived an unremarkable and unpretentious life. He never needed anything for himself and never asked anyone for anything. This is the man who can give what he can give, but he does not ask. I would say that there is no point in speaking of pride and such things in relation to Ivan Pokrovsky—he is very far from all that, but dignity is always with him. And if you were to ask the people who were with him, they’d say, “Oh, Pokrovsky!” And perhaps they would add nothing more to that. “Oh, Pokrovsky—he’s a real man!”

The case of Pokrovsky's release after six months in a PKT (punishment cell) and solitary confinement is not an ordinary one. As a rule, before releasing a person who was emaciated, they would give them some respite in the infirmary for a week or so, or put them on the diet known in the camp as “5B.” But to subject a man who has, I don’t know if it’s a latent or not entirely latent, form of tuberculosis—and this is known, and it is in his file—to half a year in a PKT and then to add solitary confinement, this is an entirely conscious policy, a policy of a resolute directive from the administration regarding this person, and a brazen policy at that. I have already forgotten how it was, but I remember when the entire zone was writing petitions, and the entire zone was worried and very anxious about how he would emerge from that PKT and how he would manage to hobble anywhere after his release. This is a fact that needs to be comprehended; it has various dimensions, this fact. I think it wasn't by chance that we were so worried—it was about his fate, his personality, and the fact that this man was capable of such recklessness without any visible necessity. After all, it wasn't about some decisive battle where one could risk one's life, but simply about solidarity with other zeks. And any one of them could go on a hunger strike or be sent to a punishment cell, for they still had the strength and were younger. But when this man does it, he is an unusual man; people begin to think about this man—he is different from the others: either his instinct for self-preservation is weakened, or he is simply a man of great faith, confident in the belief that he who seeks to save himself will lose himself, and he who gives of himself will save himself. Those who were approaching the end of their term, especially after 25 years, were completely passive in their last six months: “I'm no longer in the zone. Don’t count me in, boys, I’m not taking part in anything anymore.”

July 25, 2002.

Prepared by Vasyl Ovsienko on December 22, 2008.

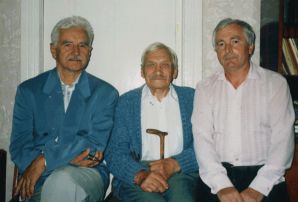

PokrovskyjSvOvs –2098, k.35A, July 25, 2002. In the town of Horodnia in the Chernihiv region, the 25-year prisoner Ivan Pokrovsky was visited by Yevhen Sverstiuk and Vasyl Ovsienko. Photographed by Oleksandr Suhonialo. Image by V. Ovsienko.