BALYS GAJAUSKAS ON VASYL STUS

In October 2000, I once again traveled to Kuchino for an academic conference on totalitarianism. I was also there as a living exhibit of the Perm-36 Memorial Museum of the History of Political Repression and Totalitarianism, which has been operating since 1995 in our painfully familiar concentration camp. While still at the hotel in the town of Chusovoy, Perm Oblast, on October 2, I met with my former cellmate, the Lithuanian Balys Gajauskas, and his wife, Irena Gajauskienė.

A former partisan, Balys Gajauskas served 25 years of imprisonment (1948–1973). He was arrested a second time on April 20, 1977, and on April 12–14, 1978, he was sentenced to another 10 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile. While in captivity, he mastered many languages. He can read in practically all European languages, at the very least. He complained that he had started to forget Korean, Japanese, and Chinese, as he hadn't read anything or spoken with anyone in those languages for a long time. He was released from exile on November 7, 1988. He was elected a member of the Seimas and headed the commission investigating the activities of the KGB. And this was after 37 years of captivity!

I showed Balys and Irena a photocopy of a manuscript by Vasyl Stus. And Mrs. Irena said:

“Why, I’m the one who carried this out…”

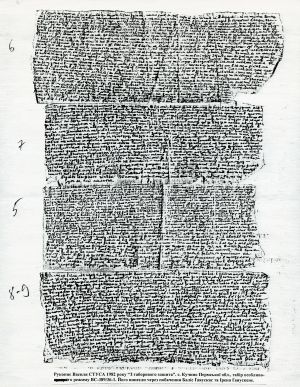

Balys Gajauskas explained: In the first half of 1983, Vasyl Stus and I were in cell 20. I had a visit coming up. I took these small sheets from him, rolled them up with my own papers, and hid them. I didn't know what was in them. I had no time or opportunity to look. I assumed they were poems. And along with my own texts, I passed them to my wife during the visit.

Irena Gajauskienė: The little packet was as thin as a knitting needle because the paper was very thin. I used to buy this kind of paper for Balys at a pharmacy in Kaunas.

This was in the summer of 1983—in June or July. After the visit, I went to Moscow and gave this packet to the Moscow dissidents. When I got home, I wrote a letter to Balys telling him that everything was all right. Because they could have searched me on the train. The Muscovite women who came for visits were searched both before and after. But for some reason, they didn't search me.

This, by the way, was our last visit in Kuchino. The next year, in response to my inquiry about when I could have a visit, I received a reply that Balys had been deprived of his next visit and parcel for a “violation of the regime.” At that time, Balys's mother fell ill and died a month later. And Balys was in the punishment cell then. For three years after that, Balys was not allowed any visits or parcels.

Balys Gajauskas: I always signed my articles with my name and indicated the date and place. My last article written in Kuchino was called “Occupied Lithuania”… No, the last one was “On the Situation of Workers in the Soviet Union.” It was very long: 50 of those small sheets. I wrote it over a long period because it was very difficult to write. Sometimes, for weeks, there was no opportunity to write anything down. They are always looking through the peephole. And I also had to hide it from some of my cellmates. I had the whole article in my head, down to the smallest detail. After that article, I thought, “That’s it, I’m not going to write anymore. I can’t take this kind of tension. The risk is too great.” Then, two KGB agents from Lithuania arrived and showed me that same article, printed in a foreign journal. “Do you know what this is?” “No, I don’t.” “Take a look.” “So what?” “You know very well that this means a new sentence.” I didn't renounce the article, but I didn't confirm my authorship either. I hardly spoke to them at all. But after that, I finally decided that I would not write again until the end of my term. But after the publication of this article, I was repeatedly put in the punishment cell, and in March 1986, with less than a year left in my sentence, they attempted to kill me. A cellmate, a former criminal and now a political prisoner named Boris Romashov, stabbed me several times in the heart area with a mechanical screwdriver. I fell under the table, and the wounds went in at an angle—the screwdriver didn't reach my heart… (At that time, Balys Gajauskas suggested that the KGB could have sent Romashov to kill Stus. He could have done it out of hatred for Stus, due to his chauvinistic beliefs, for selfish motives, or because of his psychological deviations).

If it’s just one piece of paper, I can swallow it if there's danger. But sometimes they would unexpectedly transfer me to another cell—and the papers would be left behind. I still remember where I hid them in the toilet when I was in the “cell-free” regime. I looked yesterday: those holes have been filled with concrete. They didn't find my papers; apparently, they just did some renovations there.

V. Ovsiienko: You know, I found one of my papers. It's not a very important one: it's a translation of Kipling's poem “If,” handwritten by me from Vasyl Stus's version. On the morning of December 8, 1987 (by then I had already been transferred to the cell-free regime), I saw a whole cloud of guards moving from the guardhouse into the zone. And I had this poem with me, which I wanted to learn by heart. To prevent them from confiscating it, I quickly went around a corner and stuck the piece of paper under the roofing felt that covered the insulation of a heating pipe. It was a structure less than a meter high. That day, a “general shakedown” was conducted in the zone, and the 18 of us who remained—the “especially dangerous recidivists”—were taken away in Black Marias to another zone, 70 km away, at Vsekhsvyatskaya station. Why? The name “Kuchino death camp” had become all too common in the Western media. On that very day, Gorbachev was meeting with Reagan in Reykjavik, and he needed a half-lie, at least for one day: “But they are no longer in Kuchino.”

So, on August 31, 1989, as a free man, I visited that zone again. We came to retrieve the mortal remains of Oleksa Tykhyi, Yuriy Lytvyn, and Vasyl Stus to rebury them in Kyiv. At that time, they did not permit the exhumation, saying: “Unfavorable sanitary-epidemiological conditions.” But we did enter the zone. It had been abandoned: the gates and doors were open, and local residents were carrying off whatever they needed: floorboards, glass, slate… I remembered my piece of paper, stuck my hand under the roofing felt, and pulled it out. The text had faded a little, but it was still legible. I still have it.

Balys Gajauskas: Yes, Stus translated Rilke. He threw out the drafts, of course.

V. Ovsiienko: Stus and I were in the same cell (No. 18) for a month and a half, in February–March 1984. He once told me: “I had two or three ways out of here.” Meaning, he had managed to send information out of Kuchino two or three times. Now I know that one of those times was through you. That little packet reached Germany, getting to Volodymyr Malenkovych, a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group who was then working for Radio Svoboda. He passed it on to Nadiya Svitlychna in New York. She later told me that she had been able to read the text even without a magnifying glass, although the writing was very tiny. Now I know who was instrumental in this matter.

Irena Gajauskienė: In 1978, along with Balys’s documents, I brought out a text by Ivan Hel from the Sosnovka zone in Mordovia.

V. Ovsiienko: He wrote a book there called *Grani kultury* (Facets of Culture). Perhaps that was it.

Irena Gajauskienė: That was the first time. I brought Balys clean, thin paper then. And each time, I would bring clean paper in and take out papers with texts on them.

Balys Gajauskas: It was easier in Mordovia. Many people got information out from there. But that's precisely why they moved us out of Mordovia—because there were channels. In 1980, when we were being moved from Mordovia to the Urals, someone asked the camp chief, Nekrasov, where they were taking us. He replied: “You are being taken to a place where you will not write.”

So, Stus wrote even where writing was already a crime. Especially things like “From the Camp Notebook.” These 16 small sheets take up 12 pages in the book, but their explosive power was such that it destroyed Vasyl himself. I believe that one of the reasons for his destruction was the appearance of this text in print in the West.

The second reason was the nomination of his work for the 1986 Nobel Prize. Vasyl Stus's poems were published in several languages. The world saw the caliber of the Ukrainian poet's talent not through the prism of dissidence, but as an artistic phenomenon. A nomination committee was formed, and the prize would have been awarded. But Moscow thought otherwise, even though perestroika had already begun and the reformer Mikhail Gorbachev was in the Kremlin…

In 1936, Adolf Hitler found himself in a similar situation. That year, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Carl von Ossietzky. But he was in a concentration camp. Hitler ordered his release, but while the bureaucratic machine was getting into gear, he died…

Moscow, however, acted preemptively and dealt with the Ukrainian candidate in the traditional Russian way: “No person, no problem.”

After all, the Nobel Prize is only awarded to the living…

Vasyl Ovsiienko. “Gibel Vasylia Stusa” [The Death of Vasyl Stus] // *Zerkalo nedeli*, no. 34 (409), September 7, 2002, p. 12; Vasyl Ovsiienko. *Svitlo liudey: Memuary ta publitsystyka* [The Light of People: Memoirs and Journalism]. In 2 vols. Vol. I / Compiled by the author; Art and design by B.Ye. Zakharov. – Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2005, pp. 291-294. (Translation by the author of the book).

Vasyl Ovsiienko, Irena Gajauskienė, Balys Gajauskas. Chusovoy, Perm Oblast, October 2, 2000.

A portion of Vasyl Stus's manuscript “From the Camp Notebook,” brought to freedom by the Gajauskas family in 1983.