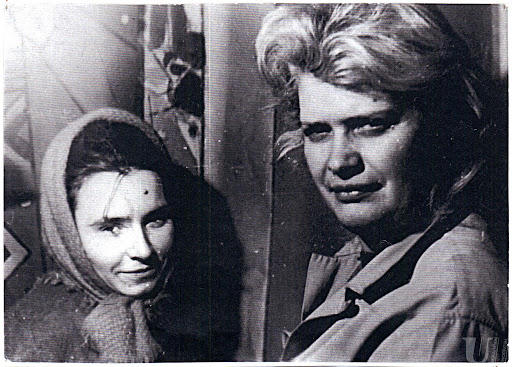

45 years ago, in September 1964, the leaders of the young Ukrainian movement, who would later be called the “Sixtiers,” celebrated a double birthday. Alla Horska and Ivan Svitlychnyi were celebrating their “70th birthday for two.” Today, it would be, believe it or not, their 160th… Of the two birthday honorees, Alla Horska was two days older: she was born on September 18, 1929.

Alla Horska is a symbolic figure in the Ukrainian Sixtiers movement. Her fate is both unusual and indicative of her time. She came from a Soviet-style “prosperous” family—yet she dared to confront the state system; she did not manage to experience arrest and prison-camp ordeals—yet she, the daughter of a rather high-ranking “nomenklatura” official, was twice expelled from the Union of Artists for the ideological incompatibility of her work with the “leading and guiding” role of the only party at that time; finally, her very death became a sinister sign of the times. The circumstances of Alla Horska’s death remain unexplained to this day. But although there is no direct evidence of the Soviet special services' involvement in this crime, it is obvious: this was a completely conscious, insidious blow to the Ukrainian revival, one of its first losses—incredibly tragic and painful.

Today, on the building on Tereshchenkivska Street (formerly Repina), where Alla Horska lived with her husband, also a prominent Sixtier artist, Viktor Zaretsky, there hangs a memorial plaque where there are always fresh flowers. But back then, 45 years ago, the state “honored” their home and their family only with constant surveillance, repressions, and provocations. For this was one of the centers of “disloyalty,” a meeting place for creative, concerned, free-spirited people. Literary critics Yevhen Sverstiuk, Ivan Dziuba, Ivan Svitlychnyi, poets Vasyl Stus, Mykola Vinhranovsky, Ivan Drach, artists Opanas Zalyvakha, Liudmyla Semykina, Veniamin Kushnir, and many others, whom the authorities of the time would have preferred to see together only behind the barbed wire of Siberian or Mordovian concentration camps, visited here.

And indeed, many visitors to this apartment would later face arrests and years of imprisonment and suffering. But the “builders of barracks” (a phrase by Y. Sverstiuk) probably hated Horska herself especially—because she dared to challenge not just their cannibalistic system, but also the very environment from which she herself came. That is why she became one of the first among the Sixtiers in the sad list of victims of the struggle for human freedom and dignity.

Before that, there was the brutal destruction of a large stained-glass window in the foyer of the Red Building of Kyiv University, where an angry Kobzar embraced a wronged Ukraine, and an inscription proclaimed: “Возвеличу / Малих отих рабів німих, / Я на сторожі коло їх / Поставлю Слово” (Horska worked on this stained-glass window together with Opanas Zalyvakha, Liudmyla Semykina, Halyna Sevruk, and Halyna Zubchenko), then—the already mentioned expulsion from the Union of Artists. Horska was reinstated in the Union, but soon she began to provide moral support to repressed members of the resistance movement. She signed letters of protest, attended trials, supporting the accused—and she was expelled a second time.

And on November 28, 1970, Alla Horska tragically died at the hands of a murderer in Vasylkiv. Her funeral gathered, in fact, the entire cream of the Ukrainian intelligentsia of that time—despite the fact that the “organs” had personally approached many “unreliables” with a warning: do not appear at the funeral ceremony. Yevhen Sverstiuk, Oles Serhiienko, and Ivan Hel gave farewell speeches. Vasyl Stus read a newly written poem in memory of Alla Horska:

Ярій, душе. Ярій, а не ридай.

У білій стужі сонце України –

а ти шукай червону тінь калини,

на чорних водах тінь її шукай.

A short time would pass, and many of those present at this funeral would be arrested and imprisoned. The Ukrainian resistance movement would continue its via crucis. And the name of Alla Horska would remain a symbol of indomitability, of creative and civic courage and honesty—and it is in this way that it has entered our times, the times of an independent Ukraine, where this courage and indomitability are so needed to preserve freedom from the encroachments of new janissaries and imperially-anxious “neighbors.”