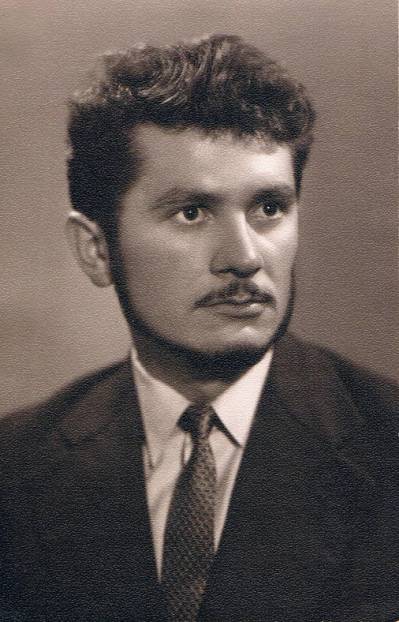

Ivan RUSYN

STAGES

A wise person once said: “Those who take the first blows in a great war rarely celebrate the victory. But the memory of them lives on for ages and resonates in the hearts of their descendants with a poignant ache and filial gratitude...”

At last, the mock trial was over, and the verdict was announced. So, the decision had been made. There was no appeal from us (Yivha Fedorivna Kuznetsova, Oleksandr Martynenko, and me, Ivan Rusyn). None of us knew where we would be taken for our “future places of residence.” They shaved our heads, cut our hair, and issued us our underwear and clothes, but they wouldn’t say when or where we were going.

The librarian, who was also the barber, did tell me that I would probably be held in this same KGB prison, as I had less than four months until my release date. But that’s not what happened, probably because they were forced to comply with the verdict, which specified my place of residence—a strict-regime camp. And so, one day, we heard a commotion in the corridor, and soon the “kormushka” (the food hatch in the door, through which they passed food and all sorts of instructions) opened, and the command rang out: “s veshchami” (with your things).

It was somewhat unexpected, as we had grown accustomed to the quiet routine of our confinement. We were no longer summoned for interrogations or court hearings—nowhere, really. They gave us food and even allowed a package from home. In short, people are people; they get used to anything and don’t want extra trouble or change. But what can you do? The master knows what he’s doing. If it must be done, it must be done; he knows better where we’ll be more comfortable and how we should live.

So I grabbed my bag, sat for a moment for the road, and looked around the cell to memorize the interior, so I could later tell the story of where my “primary education” began. I call it primary because my “universities” were, in fact, in the camp, in Yavas, Mordovia. They loaded us into the “voronok” (a prisoner transport van) one by one in the prison yard. They weren’t in much of a hurry, so I was able to get a good look at the rather spacious courtyard inside the KGB quarter. The so-called internal prison looked like a four-story brick box set in one of the corners of the yard—a typical Stalinist architectural structure.

They placed us (Yivha Fedorivna, Sashko, and me) in individual “boxes” and drove us to the train station. But they brought us somewhere far away, as the station building was not visible, and there was no one to be seen at all. Apparently, the place where they assembled and filled the so-called “vagon-zak” (prisoner transport car) was a specially designated railway track.

Escorted by vicious dogs and guards with automatic rifles, we were moved into the car. A “vagon-zak” is a special, compartment-style car for transporting “zaklyuchonnykh” (prisoners) in stages. That’s why it’s called a “zak.” The compartments in this car have transparent, barred doors with sturdy bolts. Guards, who from that moment on were in charge of us, constantly patrolled the corridor. They could see everything happening in the compartments and hear everything that was said. Sometimes, if they felt like it, they would give us a little water and take us to the latrine. But all this happened only after long pleas, demands, and a collective outcry, as everyone could hear these requests. It was a form of solidarity.

And all this communication was sheer profanity, or as some philologists say, in the “Turkic dialect.”

They put me and Oleksandr Martynenko in one compartment, the first one, I think. Yevheniya Fedorivna Kuznetsova was placed next to us, in the second compartment, alone. It was then we felt a certain advantage of being political prisoners—we were separated from the rest of the crowd. And that crowd was packed in tight. There were probably ten people, maybe more, in each compartment. A platform could be folded down from between the upper bunks over the aisle, which allowed five or six people to lie down on the second tier. Just try to imagine such travel conditions. Below, four or five people sat on each bench. There were cases when they were stuffed under the benches as well, where there was no space for luggage. And, as was later explained to me, those who squeezed in there were the so-called “pityukhy” (roosters). The things that happen in this sinful world.

As for food, the travel ration was well thought out: herring, mostly rotten, and half a loaf of bread. And water, as already mentioned, was hard to come by. It was part of the technology.

And all those compartments, both men's and women's, were completely crammed. But those passengers, apparently, didn't feel any particular discomfort, as they were probably used to such journeys. It was we who were shocked by what we saw and heard. Sashko and I were doing so-so, but poor Yivha huddled in the corner of her compartment and just prayed.

I hadn't known Yivha Fedorivna before our arrest, although they made us accomplices. It was only when I was reviewing the case files after the investigation that I got to know her in absentia as a person of high moral character. So for her, this was a real shock. She must have seen and heard even more of that filth during subsequent transports. I never saw her again.

I was later told that she was in an extremely depressed state in the camp, became seriously ill, and soon after returning to Ukraine, she passed into the other world, as if she had been released from the “big zone.” In her last days, she was cared for by her son, who buried her as God commands. Unfortunately, she has yet to be properly honored by the nationally conscious Ukrainian community. Perhaps because she was not a public figure. She worked as a lecturer in the chemistry department at Kyiv State University. As the repressive KGB authorities later classified it, she conducted “anti-Soviet nationalist propaganda and agitation” among students and teachers. She was tracked down and arrested. The henchmen of the penal system considered her underground activities the most serious crime, and in our joint case, she was the “parovoz” (the locomotive).

She was sentenced to 5 years, Sashko to 3, and I to one year in a strict-regime camp, even though the Code of Criminal Procedure did not provide for a strict regime for women and first-time prisoners. But what can you do? Such was the “most humane Soviet justice.”

This, of course, is a kind of lyrical digression. So please forgive the deviation from the topic of the transports. Similar lyrical asides may occur later on as well.

So, we sat in that “compartment” car for probably about six hours while they filled the entire northeast-bound train with “passengers.” They attached us to some mail train, and sometime in the evening, we set off. And that's when the dialogues I mentioned earlier began. You see, our “service staff” didn't want to dirty the tracks before the train started moving. But if only the wait hadn't been so long, and in the heat, too, as it was already May. True, in extreme situations, the guards would provide some containers (bags, bottles). But that came with a huge scandal.

The mail express clattered along slowly, with frequent stops. And yet, the journey was not dull; there were countless arguments, quarrels, and even fights. And all of it was accompanied by that mighty “dialect.” For us, it was a certain education, as we had never heard or seen anything like it before. A real cesspool. I think it’s hard to even imagine.

A little of what I saw. I recall these scenes. A guard is taking one or two zeks to the toilet. Passing the women's compartment, a zek asks: “Light up my soul!” But he's not allowed to stop; the guard shoves him along. But on their way back, they get the chance to behold a great variety of those “souls.” The women, probably also terribly bored, display all their charms with such enthusiasm that the souls of the onlookers rejoice at the “souls” on display. And everyone is satisfied; everyone is amused. Especially when they push each other away from the barred opening. The “salabony” (rookie) guards also enjoy it, even as they command them to “prekratit bezobraziye” (stop this outrage). This “merriment” went on for quite a long time. If it's just a human-like creature, what can you expect from it? Apparently, some people also become creatures in extreme situations. And so began my journey to that “university.”

After a while, the passengers gradually calmed down and settled. They somehow got situated and, apparently, dozed off. Our neighbor Yivha was silent the whole time, or maybe she was napping. To one of Sashko’s questions, she replied with a single phrase: “May the Lord protect you.” A rather lively conversation was going on between me and Sashko. It began with clarifying some circumstances of the investigation. There was a lot I wanted to clear up...

A brief backstory. We met in Kyiv in 1964, although we had both studied at the same geological exploration faculty of the Lviv Polytechnic Institute. I graduated with a degree in geodesy in 1959, and Sashko Martynenko graduated in geophysics about two years later. We grew close during rehearsals for the “Zhaivoronok” (Lark) choir. We had interesting conversations on historical and patriotic topics. We talked a lot about literature and poetry. I recall he even wrote some poems. At that time, I was into the modern poetry of young poets. Later, we moved on to samizdat. We jokingly called it “kramola” (sedition). The KGB agents later enlightened us: with the help of expert scholars, they explained to us that these were anti-Soviet, and mostly nationalist, documents or materials. But reading or discussing, or as my grandmother used to say, “philosophizing,” doesn’t require much intelligence. It was time for us to do something ourselves.

So Sashko found a typewriter somewhere and brought it to my place, since he was living in a rented apartment. I made an arrangement with Lida Melnyk, who knew how to type because she worked in some editorial office. And so the work of retyping samizdat began. At first, it was poems by Vasyl Symonenko, some by Ivan Drach, Mykola Vinhranovskyi, and Lina Kostenko. Then we moved on to Vasyl Symonenko's “Diary.” And from there, we got to the real sedition, such as “Sviatoslav Karavanskyi's Lawsuit Against the Minister of Education Dadenkov” and “Regarding the Trial of Pohruzhal'skyi.” That was about the scoundrel who set fire to the archives of the National Academic Library by sprinkling the books with phosphorus. Later, we organized the photocopying and reproduction of works by Ivan Koshelivets and others.

It was still the time of the “Khrushchev Thaw,” and we, one might say, paid no attention to deep conspiracy. And we were later taught a lesson for such recklessness. But Sashko and I were not the only such uneducated neophytes. Even such “masters” of the Sixtiers as Ivan Svitlychnyi and his inner circle did not recommend playing at being an underground movement or conducting any literacy campaigns in the catacombs. One could talk a lot about those years, 1964-1965. Some things, of course, have been forgotten, and there’s nothing to be done about it.

What has a beginning must also have an end. And so the time of reckoning came for our “underground.” On August 28, 1965, a roundup was carried out, or as it was later called, “the first harvest.” And all of us, those primitive “underground activists,” were swept up without warning, suddenly. But the KGB had prepared thoroughly and carried out this action simultaneously in many cities across Ukraine. More than two dozen, maybe even more, members of the nationally conscious intelligentsia were arrested.

While in the camp, in a calm environment, we analyzed that repressive action. And the vast majority agreed that we had been very naive and inexperienced. Or, to generalize, one could confidently say that the neophytes in the catacombs were much more organized and experienced.

True, this may only apply to those who allowed themselves to be swept up by that KGB broom at the end of August 1965 in Kyiv, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Lutsk, Odesa, and other cities. Because I cannot believe that the resistance to the Communist-Bolshevik empire in Ukraine was upheld by just those twenty-something individuals who were later called the “Sixtiers.” I am sure that there were many, many times more of them. For such a great nation cannot remain in bondage for long. Revolutionary upsurges happen in waves. Each generation pushes its leaders to the forefront, and they become the engines of progress, perhaps even heroes. It often happens that they are repressed by the ruling regimes, even die for the idea. But all this has never been in vain. The struggle, blood, and suffering for freedom always, with God’s help, bring freedom to the people and independence to the state.

But that’s probably enough, for I’ve gotten too talkative and strayed too far from that vagon-zak, from that compartment for two “politicheskiye” (political prisoners) traveling in stages to places “not so remote.”

The “Khrushchev Thaw” was still continuing by inertia, and they weren’t sending people to the Urals and Siberia just yet. All the “anti-Soviets” at that time ended up in Mordovia. We were probably heading there too. So our mail train was slowly chugging along; the passengers must have dozed off, because everything fell silent. Oleksandr and I did manage to clarify some questions from the investigation period. Overall, there was no frank, sincere analysis of our testimonies. He somehow retreated into himself, remaining withdrawn even in the camp. Something was weighing him down. Maybe it was something family-related, or maybe a certain dissatisfaction with the investigation and the verdict. He once said something like: “It’s easy for you, you’re going back soon, your wife and child are waiting for you, but I only have my old mother, who might not live to see me return.” There’s no arguing with that. But still...

Our sentences, compared to the later repressive punishments in the 70s and 80s for the same “crimes,” were child’s play. That is, later they would hand out sentences of 5 to 10 years, plus 5 years of exile to the remote regions of the empire, all the way to Magadan.

They brought us to some station, or rather, to some dead-end track, early in the morning. And again, in the same way, with vicious shepherds at our sides, with shouts of “Begom, begom” (Run, run), they loaded us into black “voronoks” and brought us to a prison, which later turned out to be in the city of Ryazan. There, they processed us one by one, according to the number of “dela” (files), and then pushed us all together into some hall. It was there that Sashko and I finally saw and felt the delights of the criminal world. At first, they rushed to ask where everyone was from, looking for fellow countrymen, or more correctly, “huddling by zones.” Right then, while the guards were sorting out the accompanying files, they started brewing chifir. This was done in a half-liter aluminum mug by burning a rolled-up newspaper underneath it. There were three or four such brewing stations. The room filled with smoke. By the time the guards realized what was happening, the chifir-tea was already brewed and hidden away to steep. At the same time, the inspection of bags and sacks began. That is, a voluntary-compulsory “sharing” with one's neighbors. In this way, Sashko and I were relieved of our excess baggage, our “sidors” (knapsacks) with packages from home for the road and some items bought in the commissary of the pre-trial detention center. They also took or exchanged our clothes. They gave us nicknames (klichky), as they all communicate using those nicknames. Oleksandr became “muzhik” (man/peasant), and I became “ochki” (glasses). We intuitively understood that we shouldn't resist.

Their ritual of getting high began. They sat in circles, apparently by their home zones. We were also invited, but we declined. No one insisted, as it meant more for them. They sliced our Ukrainian salo with razor blades, set out the drinks, and began... The mug was passed around the circle. You had to take two sips, no more, or you could get a slap on the neck. It was strange and perhaps even upsetting for us, but all these impressions from what we saw somehow balanced our mood, because you don’t get an education for free. And especially such spectacles. After the chifir, the smoking of hand-rolled cigarettes began. Probably with some “durka” (dope) in them, because those cigarettes also went around in a circle. Afterward, everyone sort of half-reclined—and went into their own world. They called that state “gnat kino” (running a movie).

Sashko and I also lay down as best we could. But we weren’t allowed to doze off. The bolts clanged, and our Article 62 was shouted through the open door. And they pulled us out of that “honest company.” They placed us separately in boxes. We sat in those kennels (0.8 x 1.0 meters) for maybe an hour, and then they took us for the next stage of our transport. The transfer to the train took place according to the regulations of the guard service. The same dogs, the same red-epauletted guards with automatic rifles, and commands to move at a run.

There were already three men in the compartment. They were Jehovah’s Witnesses. At that time, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Pentecostals, and some other sects were also persecuted and sentenced under Article 62. They tried to start a conversation about their own things, as if to recruit us, but found no support and left us alone. The car was not overcrowded, so they took us for a walk to the toilet quite soon. There were no amusing situations like the previous evening. We had the same herring with bread for dinner, washed it down with water, and went to bed. We met the dawn in a large city, Penza. In the same way, with dogs, men with automatic rifles, and at a run, we were transferred to the prison.

When they were processing us and conducting the sanitary treatment (haircut, wash, and all clothing put in a delousing chamber), one of the receiving officers asked where we were from. Hearing the answer, he said meaningfully: “Oh, the khokhly are coming again.” They put the two of us in a strange cell, which was taller than it was long or wide. The walls were concrete, unpainted, and not smooth. Under the ceiling was a tiny barred window. There was a slightly raised platform for lying down, a toilet, and a water tap. Later, we were told that these were death row cells. They passed some kind of thin soup, a ration of bread, and boiling water through the “kormushka.” Sometime later, they even took us out for a walk. After moving around a bit, we started to look around. The prison was a very solid structure of red brick. Huge, two and three stories high. It seemed to me as if it were on a hill. And this prison, as we were told, was from “Catherine’s times.” The guys who were transported through Kharkiv said that the Kharkiv prison was of the same type. And also on a hill, on the so-called Cold Mountain. Such symbolic hilltop structures. In Soviet times, prisons and “zones” were built in lowlands, with high groundwater levels, to prevent digging tunnels. We spent six days there, in that citadel.

One day, towards evening, they took us for transport again. The procedure of moving from the prison to the train was the same as prescribed by the regulations. The placement in the car, the compartment, and all subsequent measures prescribed by the rules for transporting zeks, right up to “otkhoda ko snu” (retiring for the night), passed uninterestingly, with nothing memorable. We met the early dawn in Ryazhsk. It was still a bit dark, and the guards were very nervous, very afraid of something. Their anxiety was transmitted to the dogs, which started a frantic barking. For some reason, there were no vehicles, and they hustled us to the prison at a jog. It was a good thing it wasn't too far and we didn't have heavy bags. Otherwise, how we would have struggled with those “sidors.” Exhausted, we were received from the exhausted dog handlers through wide-open gates. And again, one by one, according to the number of folders, they counted us and herded us for sanitary processing. Then they led both of us into a huge hall with multi-row, two-tiered iron bunks, or maybe it was also a cell. We found some old man there. Later, they gave us something to eat, and after a while, they took us out for a walk. There was nowhere to look, as the exercise yards were enclosed by a high wall. And in general, it was a prison like any other, without any special features. Or maybe I had already grown accustomed to those peculiar conditions of confinement.

Somehow, we slowly got to talking. He asked us where we were from, under what articles we were sentenced, and where we were headed. And then he began to “enlighten” us, as he was a long-time prisoner. He told us a little about himself, that he was heading to Moscow, that he “resided” permanently in zone 385/11 in the settlement of Yavas in Mordovia, where we were obviously being transported. He also informed us that the prisoners in that camp were from the war and post-war years, mostly nationalists from Ukraine, the Baltics, and a few from other regions of the empire. Later, taking advantage of our willing ears, he got carried away with telling his “legend.” His last name was Ivanov. He was supposedly a colonel in Vlasov's army and made it to Paris by the end of the war. There was much talk about the beautiful life in France. And suddenly, in 1946, in a restaurant, a waiter hands him an invitation to a telephone call. In the phone booth, they grabbed him, gagged him, and with a pistol in his side, led him out, pushed him into a car, and took him to the embassy. And then to the Union—and to a tribunal. He was given the highest measure of punishment—execution by firing squad. But why, he himself didn't know. Then his treason was re-evaluated to 25 years. Such cases happened often. I remembered his legend because he said, with complete seriousness, that his brother, also named Ivanov, was a general and perhaps the head of the Moscow commandant's office. And that he had been taken to see him more than once, and they always wanted some statement or information from him. I didn't quite understand what kind of information, whether Vlasovite-staff related, because he presented himself as the deputy chief of staff. In the camp, I learned that he was one of the stool pigeons-informants. So, apparently, that’s where he went to give information. We stayed in Ryazhsk for about three days.

Next was Ruzaevka. A prison without adornments, gray, obviously a typical Soviet building like all the others. They kept us there for less than two days and again, with all honors, took us for the next stage of our transport journey.

And the last transit prison was at the Potma station. From here began a narrow-gauge railway branch, along which there was a penal camp at every kilometer. This was one of the former Stalinist archipelagos of camp-zones. There were at least twenty camps in that archipelago. Of them, at that time, about 6 or 7 were special—political. Of course, conditionally political, because what politics did those policemen or Vlasovites have? But that's by the way. More details about them will be in the section about that 385/11 zone.

They herded all of us together again, a mix of different people, into a rather large cell. Along the walls, there were wooden platforms raised slightly above the floor. People lay and slept there. The building itself was a one-story, barrack-type structure. And it was here that I first saw a classic “parasha.” It was a rather large metal tub, much bigger than a so-called “vyvarka” (laundry boiler). And it was obviously mass-produced. It had sturdy horizontal handles so that two people could grab it from each side, because in the morning and evening, this “parasha” had to be cleaned and disinfected. Forgive the detail, but many have heard this word, and few can imagine what it is.

Sashko and I were also taken aback by the medical service. Every day, after the so-called breakfast, there was a medical inspection. The “kormushka” would open, and they would ask if “bolniye yest” (are there any sick people). Almost everyone would shout that yes, there are, and would stick their hands through this little window. They would be given two or three white pills each. The same for everyone, because they didn't ask what anyone was sick with. There was one diagnosis for all—“bolniye” (the sick). After the window closed, these pills would be collected by two or three “sick” people, who, after carefully chewing them with water, would swallow the mush. Then they would lie down and wait for the “prikhod” (the high). Whether they got any “high” from that white substance, I don't know. Most likely, the “high”-stupor they got was from the ritual itself. They kept us there for about three days as well.

As always, without warning, the cell door opened, and on the command “s veshchami,” they began to separate us all according to the residence indicated in our “delo” (file). Then the convoy took us under their care, and loaded us into the small cars of the narrow-gauge railway. They fumbled for a long time with dividing us into the fenced sections of the cars. It was very hot, and they gave no water. And in general, they didn't listen to anyone, because all the guards were very nervous. Even the dogs.

Finally, the train set off on its long journey for many, many years. Of course, this is from lyric poetry; in life, everyone has their own road and their own years. At each camp, there was a stop and a disembarkation according to the same statutory rules and actions with dogs and automatic rifles. At the eleventh stop, they disembarked me, Sashko, and four other religious sectarians. Thus ended the transport journey to the zone that would become my university with an accelerated course of study. This travel narrative could be enriched or embellished with many more episodes from those transit prisons. People, especially in extreme conditions, and even more so zeks, need to talk. And everyone develops, creates their own legend.

ZONE ZHKh-385/11

The number 385 is the number of the Mordovian micro-archipelago from that great imperial, Soviet GULAG archipelago. And there were, across that vast evil empire, obviously many times more of them than the 385 of that Mordovian one. The criminal zones of the 385th archipelago were mainly populated by people from the Moscow region. The special, that is, political zones, were populated from all over the Union. Our eleventh camp held about 1,200 people from all the republics. The vast majority were Ukrainians, among whom the largest group was former UPA fighters and OUN members. There were several “esbisty” (members of the Banderite security service). They were the most organized and monitored the relationships between different political or national groups. That is, they maintained internal order. This is perhaps somewhat similar to the role of “pakhans” in the thief-gangster zones.

During my time in the zone, all the political prisoners, or dissidents, or as they were later called, dissidents, generally grouped together based on ideological grounds. Like the Banderites and Melnykites, social democrats and liberals. But only the Ukrainian nationalists had the luxury of dividing themselves, probably on the principle of “because there are many of us.”

The Belarusian nationalists adopted the name “Lytvyny,” and they called the citizens of modern Lithuania “Zhmudy.” Their leader was a highly educated former teacher. He had a fine collection of literature on history and geography, as well as a considerable body of research on his historical ethnicity. Here I want to note that this period of camp confinement was still quite liberal. It was the time of the Khrushchev Thaw. That is, it was not forbidden to have book collections, to write and draw, to form fraternities and hold debates.

Again, I want to warn the reader that my stories will not be in dark colors; perhaps even romantic at times, because I perceived everything I saw and heard as if I were a tourist in some unknown country. I did not have the pressure of years of servitude. I wanted to get a certain education and use it to at least somehow tell about what I saw and heard. But, as it later turned out, that country was not so unknown after all. It was the “small zone.” Almost the same as in the “big zone,” which was called the Soviet Union.

I was, in fact, lucky, because by the end of 1966, they began to “tighten the screws.” That is, subsequently, all privileges were revoked, and the regime of confinement became worse than even prescribed in the code. This was later told to me by those who were released after me. These were Mykhailo Osadchyi, Viktor Kuksa, Oleksandr Martynenko, and especially Opanas Zalyvakha, who was punished for 5 years. Punished indeed, because he was forbidden to draw. That is how the commie-fascists deprived Ukraine of almost five years of creative work by such an outstanding national artist.

So let’s return to that narrow-gauge train, to that last stop of my adventurous journey. They unloaded us from the car as usual. A “voronok” took us to the gates, or as they said, to the vachta (guardhouse). There they stuffed us into “boxes”—and again, the agony in the heat without water. Then, through the “shlyuzy” (gates), they handed us over to the camp guards. They counted us, checked our faces against the “delami” (files), opened a pen with a turnstile, and let us into Zone No. 11.

It was a strange feeling. No need to keep your hands behind your back, no commands of “step left” or “step right”... Well, it was like some kind of freedom, because you don't immediately notice the barbed wire fence; instead, you see space, trees, an unbarred sky. And a little in the distance, buildings and people. So the zone is indeed a certain freedom. Firstly, you can walk throughout the territory, although it is limited by three rows of barbed wire fences. Secondly, you can communicate with whomever you want. This is especially felt after an almost month-long transport journey. In those extreme conditions, the general relativity of things is very clearly realized. Imagine such a “box,” 0.7x1.0 meters, in a voronok during transport from prison to train or vice versa. Or the long wait for a transport, or a transfer to court, or elsewhere. And the same train compartments, where they cram 10–15 people, and they suffer there for 10–15 hours of the train's journey. And suddenly, a completely different reality. You can stretch your arms, run, see birds and blooming flowers. And it seems no one forbids anything. Such is relativity. Of course, this was a momentary emotional outburst. Soon everything became reality.

The first to greet us on that island of the GULAG archipelago were Yaroslav Hevrych, Ivan Hel, and Mykhailo Ozernyi. All of them were from our “draft” of the previous August. The old-timers, there were several of them, watched our joyful, embracing reunion. Afterward, they led us to a two-story building. They took us into a small room, which was the “workshop” of the so-called camp artist, Roman Duzhynskyi. He wrote or drew various camp announcements there, posters like “To freedom with a clear conscience,” and so on. Sometimes he practiced portraiture. He liked to make copies of significant works by great artists. I found him working on a reproduction of Repin's “Zaporozhian Cossacks.” In general, by that time, he had created several quite successful works. In particular, a portrait of the long-term prisoner Sviatoslav Karavanskyi, which, by the way, they managed to take out of the camp and all the way to America, where Sviatoslav himself and his wife Nina Strokata later ended up by force of circumstance. Sometime in the early 90s, Roman Duzhynskyi managed to travel to the USA and present some of his camp and post-camp works in several American cities. He obviously sold a few. In 1995, in Detroit, I had the opportunity to see some of his works. They were exhibited, and perhaps are still on display, at the Art Gallery of the Ukrainian Cultural Center, which is managed by the Kolodchyk family.

But please forgive me, as I get carried away from time to time, and one can lose the integrity or sequence of the plot. So, in that workshop, which in zek-speak was called the “shursha,” we celebrated our meeting with a “vypivon” (a drink), which they called chifir-drinking. Present there were Viktor Solodkyi, Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi, Stepan Soroka, Roman Duzhynskyi as the host, and Yurko Shukhevych. These were the peculiar activists of the Ukrainian diaspora in this Mordovian “reserve.” Once, such reserves bore the names of Beria or Yezhov, and also the leader himself, because they housed the children of all the peoples of the Soviet motherland, and he, as was propagandized, loved children very much.

And then—it was like in that fable where three people gathered and, almost without a word, instantly organized half a liter. Duzhynskyi, as the host or chairman, exclaimed: “Well, so what...” And Yurko Shukhevych, with full understanding, rushed to find a small pot, because an aluminum mug was clearly not enough. While we talked, told stories of our journey, how long it took, through which “transit prisons,” the brewed tea, or as they called it, “harbatka,” was already ready. Yurko Shukhevych was an unsurpassed master of the “kayf” (high-seeking) business. There was a whole school of masters there, some for tea, some for coffee. They even founded the Ukrainian Chifir-Balm Society. By the way, I later also went through that school, and when I was released, they even gave me a diploma with a number and a wet seal. The chairman of the society was Yu. Shukhevych. The secretary was V. Savchenko. So everything was proper, by the book, as in the good old days.

We arrived, apparently, on a Sunday, otherwise they wouldn't have been able to arrange such a solemn meeting in the middle of the day, with our reception into the fraternity. After the festivities, they took us to the barracks, according to the orders indicated in our referrals. They introduced me to the senior “dnyuvalnyi” (orderly), who was a Georgian general; unfortunately, I don’t remember his name. But I remember his life story, which he told me before my release. He was already quite old, completely gray, and stooped. He had already served more than ten years of his fifteen. He didn’t make it to freedom; he died in the camp. A tragic fate befell him in March 1956. He was the commandant of the Tbilisi garrison, a Georgian one, because until then almost all Georgians served in Georgia.

When Khrushchev began his anti-Stalin campaign and they started tearing down the idol's sculptures and removing all mentions of the “father of nations,” the Georgians, and especially the Tbilisi student body, began to protest. The protests began on the day of Stalin's death. On March 9, the protest escalated into uncontrolled demonstrations with slogans of independence. And so Moscow ordered a stop to the disorder. But the general did not order the suppression of the uprising. He knew that the Georgian soldiers would not beat their brothers and sisters. He was arrested, the garrison was disarmed and disbanded. A division was airlifted from Tashkent. He said that it was commanded by Ukrainian officers. This demonstration was literally shot up; there were many casualties. This whole story could have been his legend. But...

In 1958, I was on a pre-diploma internship in the Caucasus, in Svaneti. There were two Georgian technicians in our geodetic team. One of them, Jumber Kalandadze, was a student at the Tbilisi Topographic Technical School at that time. He was a participant, a witness to those events. He showed me the trace of a deep wound from a shot through the shoulder. At that time, I didn't really believe his stories and marks. In that totalitarian society, few knew about the events in Novocherkassk, where peaceful demonstrations were also brutally suppressed with weapons. The same thing was repeated in Tbilisi in 1989. Clearly, the Georgians are atoning for the actions of their fellow countryman, that bloody executioner of the “friendly family of nations.”

When the old general told me about those atrocities, I recalled the story of the participant and victim of military punitive violence and believed them. Such was that “Khrushchev Thaw,” such was democracy with a Khrushchevite face. Or in 1989 with a Gorbachevian one. Apparently, that communist-Bolshevik state system could not have been otherwise. For empires have always been held together only by violence. And the Soviet empire was held together only by fear, by the huge militaristic regime of the NKVD and KGB. It was only necessary to weaken the regime a little for this rotten mega-structure on a clay foundation to crumble. And there is no future for that successor of the Union empire, for it too is held together by military force. It will fall, and the numerous small nations, persistent in their struggle for independence, will achieve true freedom.

Dear reader, please do not frown. I did warn you that there would be “lyrical digressions.” And I remind you once again that my time in the camp was a period of the end of the “Khrushchev Thaw.” In the camp, one could write and draw, spend leisure time as one saw fit. There was an area planted with viburnum, where friends or like-minded people would gather for celebrations, where they would debate. And, most importantly, openly—no one interfered. It was like a strict camp with a human face. One could receive packages or parcels with salo, tea, coffee. Nadiia Svitlychna even sent us collections of V. Symonenko, M. Vinhranovskyi. Censorship was very weak. As I already mentioned, one could take out one's own, and not only one's own, notes and portraits. For instance, I was allowed to take out my portrait by Opanas Zalyvakha and Roman Duzhynskyi. Knuts Skujenieks, a Latvian poet and translator, also took out his portrait by P. Zalyvakha. Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi somehow managed to pass his to freedom. Many other works by Zalyvakha also saw the light of day then. By the way, I also managed to transport a letter—an open appeal to Ivan Drach condemning his then-collaboration with the leadership of the Communist Party. He and Dmytro Pavlychko had been sent to represent Ukraine at the UN, where they boasted about how wonderful and free life was in the Land of the Soviets. I also had messages for Ivan Dziuba and Lina Kostenko, where support and pride for their creative-patriotic work and organization of human rights actions were expressed. All this information is provided for a general understanding of that contradictory short “thaw.”

Already by the end of 1966, and then increasingly tighter, they began to tighten the screws of the regime. And not just the regime of confinement and food. All conditional privileges were eliminated. The “kumy,” or as they were also called, “zemliachky,” these operatives of the Ukrainian KGB, almost permanently resided in Yavas. Constant “shmony” (searches) were conducted with the confiscation of all notes. Opanas Zalyvakha and other creative individuals were forbidden to “pisat i malyevat” (write and draw). I remember how exhausted Mykhailo Osadchyi looked. He was released a year after me; he had served two years. And everyone who came after returned tormented and exhausted. And Opanas Zalyvakha, who suffered for 5 years, was hard to recognize. Completely gray, gaunt, stooped. He took the moral violence, that prohibition to write and draw, very hard…

I have strayed too far again; I must return to the storyline.

So let's return to the first days, or what happened next. The weather was beautiful and summery, although it was still May. It was a Monday. After breakfast, everyone was lined up on the parade ground for the morning roll call and work assignment. Viktor Solodkyi, one of those who had greeted us yesterday, informed us what we were to do and where. He was apparently the assistant to the “nariadchyk” (work assigner), or maybe just one of the “pakhans” I mentioned earlier. But the meaning of that word was completely different from in the criminal zones. Eventually, I was assigned to a construction brigade. Oleksandr Martynenko was sent to the work zone, to the woodworking shop, where they made boxes for radios. Ivan Hel was already set up there as some kind of mechanic. Yaroslav Hevrych was placed as a medical assistant in the infirmary. Those who worked “v bolnichke” (in the little hospital), in the library, or like the aforementioned camp artist—they were called “pridurki,” because it was easy, foolish work.

I found this out later, ten years later, when in 1976 I was sentenced to seven years and sent to the harshest-regime criminal zone No. 93, in the Novo-Danilovsky quarry in Mykolaiv oblast. There, such positions were given to the “kum's” workers. In our 385/11th zone, the “kumy” did not yet have a monopoly on this. A year later, everything became as it was supposed to be. Hevrych was kicked out into the work zone, Hel was deprived of his position as a maintenance mechanic. That is, everyone who was not going to repent was forced to “pakhat” (toil). In the 93rd zone, in a similar situation concerning me, the Kyiv KGB chiefs shouted at the camp kum: “V karyer ego, v kanavu, gnoit ego, suku” (Into the quarry with him, into the ditch, let him rot, the son of a bitch). And they did remove me from construction and sent me to “rot.” But that’s just an example of how relative everything is.

Since I didn’t have much time left “to pull my term,” the old-timers advised me not to try too hard, just to serve my time quietly, without problems. And not to take part in repairing the fence, because that was considered “zapadlo” (against the code). This suited me perfectly; I tried not to “stick my neck out” and “filonil” (shirked) to the fullest extent. The guards occasionally chased me back to the group. I initially had a bit of a conflict with the brigadier. He was a former policeman, some Pylypchuk from Volyn, who was finishing his sentence and trying to earn as much money as possible. In the zones then, and later too, those who wanted to work conscientiously and leave for freedom with a clear conscience had the opportunity to earn some money. One could send that money to relatives or receive it upon release. My conscience didn't bother me, so there was no need or desire to conscientiously repair barbed wire fences or level the sandy strips between the barbed wire rows with a rake. So I told the brigadier just as it was, that I didn't need the money and to leave me alone. He, with his policeman's soul, took this aggressively and tried to “turn me in.” But our senior guardians intervened, and he quieted down, stopped noticing me. And so I “reformed myself” during working hours, “atoning for my guilt” until the end of August.

But that was still a long way off. All in good time. Life, just as in the “big zone,” so too in the “small barbed-wire zone,” passes differently for everyone. Each person settles in as they can. I remember how in that 93rd zone I often heard the phrase: “He who lived well under the Germans will live well here too.” I never quite grasped the meaning of that sentence. But there must be something to it, and everyone obviously understands its meaning in their own way.

Everyone followed the daily routine as much as possible. Reveille, breakfast, then a head count in each detachment and dispatch to the work zone. To and from the residential zone, they were passed through a gate-lock with a strict count. Those who were in the work zone had lunch there. Everyone had dinner in the mess hall. There was enough food at that time; bread was in unlimited quantities. Then there were almost two hours of free time. Mostly, it was spent in conversation, strolling on that parade ground-stadium where the morning and evening roll calls were held. At 10 o'clock, it was “lights out,” everyone to their barracks and bunks. There were also night inspection raids to see if all the bunks were occupied.

And so a week passed, and then a second. I listened and watched everything, began to make some acquaintances. And I started to gain knowledge on an accelerated program. Time flew quickly for me. And then reinforcements arrived. They brought Mykhailo Osadchyi, the brothers Mykhailo and Bohdan Horyn, and Opanas Zalyvakha. The meetings were very warm, perhaps even joyful, if one can use such epithets for such circumstances. Yaroslav Hevrych and Mykhailo Ozernyi, as our old-timers now, instructed them on what to do and how. They were settled according to the same scheme as us. And again, celebrations on the occasion of their arrival, again a special collective ritual of chifir-drinking from the masterful hands of Yurko Shukhevych. And a real appetizer from their home supplies. I got the impression that only Sashko and I had been robbed in the transit prison by those cell-dwelling “hop-stopniks” (muggers).

A little later, we recovered, calmed down, and began to settle into the environment. One of the clever old-timers calculated that I was due a food parcel and a package, as half of my “term” had long since passed. That is, I needed to request permission, which was done. Soon, I received a package from my wife with smoked salo and a small bag of coffee beans. A little later, a parcel with tea from my brother. So it was “let the good times roll.”

A month, or maybe more, passed under “festive banners.” And the rest of my term didn't weigh on me. There was no time to look back at myself. The barrier of suspicion and alienation was overcome. My fellow countrymen-old-timers were convinced that I had not been sent on a special three-and-a-half-month assignment. Especially after Mykhailo Osadchyi arrived with a two-year sentence, and then someone else with one and a half years. They initially told me that I must have told Khrushchev to go to hell. They also joked that with such a term, one could “sit it out on the parasha.” In general, everyone was amazed at the KGB's stupidity, sending someone for such a short term to such a zone, where half the prisoners were sentenced to death. And such camp “masters,” or aksakals, as the Caucasians called their gray-haired Georgian general, like Mykhailo Mykhailovych Soroka and Sviatoslav Yosypovych Karavanskyi, said that I was very lucky to be admitted to this University. They said that I could learn a lot of good and valuable things, albeit on a shortened program.

So I tried to learn and understand everything. Most of those teachers or professors, knowing that I would soon be returning to the “big zone,” tried to lay out their cherished Ukrainian ideas or plans for gaining independence, dreamed up over the years. In other words, they took advantage of the availability of willing ears. Because as I later understood, they no longer listened to each other. Apparently, they already knew everything about everyone, or who was “running” what. For example, there was an interesting man named Mykhailo Lutsyk. I don't know what his education was or who he used to be in that other world. But the fact that he had learned many different things, and apparently perfected his knowledge in those camp universities, is a fact, because he too was serving out his 25 years, or maybe he had even more. In the camps, it's not customary to ask who is serving how long and for what. So I didn't ask. So, that Mykhailo had this idea, maybe it was an idée fixe. Having learned that I was involved in construction, he decided to entrust me with a mission of paramount importance, truly legendary. According to his plan, the following had to be organized. During the demolition of some old building in the center of Kyiv, while destroying the foundations, a vessel had to be found containing a letter or something from Lenin to Skrypnyk. This letter, or perhaps a charter or a treaty, would affirm the guarantee of Ukraine's independence. Just imagine! And this whole event had to be witnessed by journalists with film or television cameras! The presence of foreign witnesses was desirable or necessary. What an idea, what a fantasy! And all this was said with complete seriousness.

He also carried on about school geography, where the future territories of Ukraine were delineated. In the east—including the Don River. In the northeast—Voronezh, Kursk, Oryol, and, it seems, all the way to Smolensk. He left Minsk to the Belarusians, but the Brest and Gomel regions—those are ours. He agreed on the border with Poland along the Vistula River. As for the southwestern borders, they were along the Danube. What a State that would be! I didn't have much time to “project” with him, but I didn't argue and shook his hand firmly, with admiration. Let him be happy. These were the dreams of his conscious life. This episode of acquaintance with fantastic projects seemed to be exhausted. But no. At the dawn of independence, when the first presidential elections were to be held, Mr. Mykhailo Lutsyk found me in Kyiv. He wanted to be president. And I joined in to help him collect supporting signatures. I couldn't refuse him. I also helped him with money for a trip to the Donetsk region. For some reason, he expected great support there. He didn't contact me again after that. They said he did collect a rather large number of signatures, but not enough for registration.

Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi deserves special mention. He was a classic “esbist.” He was a true fighter against the communist hydra, fanatically believing in the independence of Ukraine. He dedicated his entire conscious life to the struggle for Ukraine's freedom. He always remained a believing optimist. I don't know what his basic education was, but in conversations or debates, he conducted dialogues skillfully, with deep knowledge of the subject. When asked how many years of hard labor he had left, he would answer: “Until the end of Soviet power.” That power kept adding years to his sentence. And they caught him insidiously somewhere in the late 40s in the Donetsk region. He was the leader of a group sent to establish underground work there. When he entered a safe house at night, they threw a net over him from the attic in the hallway, tied him up, and literally a few days later a tribunal sentenced him to the highest measure of punishment. It was later commuted to 25 years. During the camp uprisings, they added another ten. And only thanks to the collapse of the evil empire did he return to Ukraine. He lived in Lviv. Until his death, he was not duly honored in the state of his dreams. This government, supposedly no longer pro-communist, still cannot or will not honor true national heroes.

The exception, perhaps, is the heroization of Levko Lukianenko or the son and father Shukhevych. Or the heroization of the last UPA commander, Vasyl Kuk, although many questions remain that have not been clearly clarified. Maybe someday the Ukrainian SBU will open its archives, and we will be able to find out how he became the successor to Roman Shukhevych, how he allowed himself to be caught, and how he received an apartment and a creative job in Kyiv.

And a little more about Yurko Shukhevych. As already mentioned, Yurko was a universally recognized, and probably the best, chifir-brewer. Perhaps it was for these merits that he became the head of the UChBT (Ukrainian Chifir-Balm Society). I had no substantive conversation with him about anything past or present. And that’s understandable. In fact, he had nothing to share or boast about in terms of his accomplishments and actions. Except perhaps being the son of the UPA commander, who was caught at the age of 13 and imprisoned for many years for nothing. How he fared all those twenty years, for some reason, there were no stories. However, others said that he was under the care of the Banderite prisoners as an orphan and the son of General Chuprynka. He was released after serving 25 years of hard labor. He was not allowed into Ukraine. He settled in Nalchik thanks to Nina Strokata, who exchanged her apartment in Odesa for an apartment in Nalchik and gave it to him. After the collapse of the empire, he moved to Lviv with his family. There he joined UNA-UNSO and even became the leader of some branch of that organization. He wavered and often made quite contradictory statements. Such wavering regarding support for this or that prominent Ukrainian political figure. When he noticeably and at the right time leaned towards President Yushchenko, then, as the Muscovite says, he “skhlopotal” (snagged it) and received the title of Hero of Ukraine. Yushchenko handed out a great many of those heroic titles, where they were needed and where they were not. But that’s their business. History will judge.

A very colorful figure in the camp was Sviatoslav Yosypovych Karavanskyi. I knew him in absentia. The famous poet and translator Dmytro Khomovych Palamarchuk told me a lot about him in Irpin, in that glorious writers' oasis where he lived. They had graduated from Odesa University together. They seemed to have known each other from the Stalinist camps. And what also significantly helped our acquaintance was my reading of his seditious works. Perhaps the most significant points in my indictment for reproducing and distributing anti-Soviet materials were his “Lawsuit Against the Minister of Education Dadenkov...” and “Regarding the Trial of Pohruzhal'skyi.” So we met like old acquaintances. He knew about my arrest from Dmytro Palamarchuk, because he was arrested later. But he was brought to the camp sooner because there was no lengthy investigation with him. Immediately after his arrest, he was sent to serve out the remainder of his 25-year sentence. That is, a little over nine years.

They released him, reducing his term, somewhere right after the tyrant's death, hoping that he had reformed. The NKVD and KGB practiced such releases then and all the time later. But one had to write a “prosheniye” (petition) with certain repentance, condemnation of one's actions, and, figuratively speaking, sing “kak kharasho v strane sovetskoy zhit” (how good it is to live in the Soviet country). He wrote something too.

He managed to complete his philological education, but was not allowed to work as a teacher. Nevertheless, he carried out national-enlightenment work in Odesa, right up to creating and distributing samizdat. The KGB camarilla tracked him down and arrested him. He refused to speak with the KGB agents at all. And they, on the grounds that he had not reformed, sent him to serve out the term once sentenced to him.

He was a man of a powerful Cossack build. He had robust health. He often held protest hunger strikes. By nature, he was not open, did not show a need for communication. Maybe that's my personal impression. But, apparently, the most significant reason for his state and relationships was his former statement and a KGB certificate about him, posted on the начальницький (supervisory) notice board, stating that he had been an employee of the Romanian “Siguranța,” for which he had received the highest measure of punishment, commuted to 25 years. Those materials hung there for a long time, and some, of course, reacted.

I didn't pay attention to this and sincerely communicated with him in a friendly manner. We recalled our recent freedom, talked a lot about poetry, translations. He was also involved in dictionaries. He was a very hardworking person in the field of Ukrainian linguistics, and still is. His “Dictionary of Rhymes of the Ukrainian Language,” “Russian-Ukrainian Dictionary of Complex Vocabulary” have been published, and his “Dictionary of Synonyms” has been published twice with additions. Many works on linguistics and literary studies have been published. A collection of poems and translations, in particular, sonnets, was published.

He befriended Mykhailo Osadchyi as a poet and communicated closely with him. We considered him one of our own, a Sixtier. One time he declared a protest hunger strike. In political camps, and in prisons too, this is perhaps the only effective form of protest. There are individual or collective hunger strikes with support. When Osadchyi and I learned about this, we decided to organize collective support. We gathered all our people on that “clearing of free speech,” which was mentioned somewhere above. There is a rule: you need to discuss and make a joint decision on collective support for a hunger strike. Democracy. So Sashko Martynenko informed everyone of the fact and the reason and proposed that everyone support it. Mykhailo Osadchyi and I also asked for general support. But the Horyn brothers, Ivan Hel, and Mykhailo Ozernyi began to object. They said he should have coordinated with all of us. Someone else said that he often goes on hunger strikes, and for not very important issues, that these hunger strikes devalue the most radical protest action of the imprisoned. In short, they talked and talked, but did not support the hunger strike. The majority adopted an appeal to Sviatoslav Karavanskyi to stop the hunger strike. He did achieve the resolution of his demand and, of course, stopped the hunger strike, regardless of our appeal.

From that episode, I remember the process of discussion and voting. Believe it or not, but even in captivity, the division of Ukrainians into Galicians and Dnipro Ukrainians manifests itself. This is a very sad precedent. Such things happened in the past and are still repeated today. But this is by the way. I hope that this Galician “beau monde” trait has remained in the past, because the “beau monde,” apparently, has already all moved to Kyiv, on the Dnipro.

The second such classic “master” of that camp aristocracy in my memory was Mykhailo Mykhailovych Soroka. He did not have a significant, showy stature. Medium height, athletic build. He systematically engaged in gymnastics, especially “yoga.” For some reason, at our first meeting, it seemed to me that he looked very much like Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky. People spoke of him as an absolute authority. Throughout all his endless camp or prison trials, he never once faltered, never betrayed anyone. And most importantly, apparently, he never once wavered or doubted the coming victory of his life's dream. He believed in Independence. But he did not live to see it. He died in the camp. His remains were reburied in the Lychakiv Cemetery in Lviv next to his wife, Kateryna Zarytska, who also for many years, almost her entire conscious life, was punished in the inhuman conditions of the totalitarian communist-Bolshevik empire. (M. Soroka died on June 16, 1971, in camp ZhKh-385-17A, Ozerne settlement, Mordovia. Kateryna Zarytska, having served 25 years of imprisonment, died on August 29, 1986, in Volochysk, Khmelnytskyi oblast. Their solemn reburial took place on September 28, 1992. – Ed.). Their married life together in freedom was very short, a little over a year. (Only 4 months: both were arrested on March 22, 1940. – Ed.)

After our acquaintance, our conversation was on general topics. He didn't try to find anything out from me or impose his own views. I had the impression that he knew everything about that “big zone.” This impression was later confirmed by his stories. He was often taken to Ukraine and around Ukraine. They wanted to convince him of the great progress of Ukraine during the years of his absence. They dressed him up as a gentleman with a tie. They took him to theaters and exhibitions, drove him to advanced collective farms and successful factories. Even to sanatoriums and hospitals. Apparently, to Feofaniia. And all this was so that he would renounce his ideas, condemn nationalism, and, of course, praise the Soviet leaders.

Later, somewhere in 1977-78, a Kyiv KGB agent “in plain clothes” named Hanchuk and a Mykolaiv colonel named Bryk in uniform brought me several newspapers to zone No. 93. There were already highlighted statements of repentance, and they all ended with praise for life in socialist Ukraine under the leadership of the Communist Party, that is, the KGB. I remember the confession of the writer Vasyl Zakharchenko, after which he was released and supposedly later even given the Shevchenko Prize. And the Martynenko brothers. I don't know why they were pressed so hard. Sashko at that time, in the seventies, was working somewhere in the North in a geophysical expedition. And his brother Leonid, a former political prisoner released after the death of the dictator Stalin, lived and worked somewhere in a village near Hadiach. I read them. All of the same type and almost similar.

After some time, both KGB agents come again and also demand a “bamaga” (paper). Such “friendly” meetings happened several times. I defended myself by saying that I had “broken with the shameful past” ten years ago. And don't touch me, because I am under the jurisdiction of another department and will complain. They became very angry and, with curses, ordered the camp authorities to “zagnat yego v transheyu, v karyer; gnoit yego, suku” (drive him into the trench, into the quarry; let him rot, the son of a bitch). But that's by the way. Perhaps someday I will manage to tell about the adventures in that 93rd zone over seven years.

So, the highly respected Mr. Mykhailo gave them no hope, and they eventually gave him relative, and then absolute, peace.

I heard from many about his very long stay behind bars and barbed wire. How long—no one said specifically. And I didn't inquire, because I already knew that it's not good to ask. And yet, somehow later, I dared to ask him himself. So I ask: “Mykhailo Mykhailovych, forgive my curiosity, how long have you been in prison?” After a pause, he asks: “Ivasyu, how old are you?” I say that I was born in 1937. He softened, became generous, and began to tell. The Polish police (defensywa) imprisoned him in 1937. He was in the “Bereza Kartuzka” concentration camp until the autumn of 1939. “Ours” released him after the defeat and partition of Poland. Somewhere around that time, he immediately married Katrusia (as he always called her) Zarytska, the daughter of a renowned family of mathematicians. But everyone has their own fate. And so he was imprisoned again by the police, only this time it was the communist-Bolshevik, “liberating” police. And this was already “until the end of Soviet power.” For him, it turned out to be until the end of his life. At that time, in 1940, their son was born. The grandson was raised by his grandparents, the Zarytskys. His mother worked in the underground during the Soviet and German occupations. She was in charge of contacts with the world's “Red Cross” in the UPA. In the late 40s, she was tracked down and sentenced to many years. (K. Zarytska gave birth to her son Bohdan in prison in September 1940. At the age of 8 months, she gave him to her parents to raise. In June 1941, she escaped from the bombed prison. She became the leader of the women's OUN, and later, until her arrest on September 21, 1947, she was the head of the Ukrainian Red Cross of the UPA, a liaison for the Commander-in-Chief of the UPA, General Roman Shukhevych-Chuprynka. She was imprisoned for 25 years, which she served in full, almost the entire term in prison. – Ed.). He said that in Mordovia, in the hospital, which was in a common fenced zone with the women's camp, he talked, that is, shouted back and forth with Katrusia. Such things happen. And only the grave in their native land united them forever. May the earth be a feather for them, and may their souls be forever in Heaven. May they ask God to help Ukraine become the model of their dream. And eternal memory to them on earth.

The Soviet government allowed the grandfather and grandmother to raise the de facto orphan, although they could have taken him and placed him in a “detdom” (orphanage). How they managed that, I will not say. The grandson of the academicians Zarytsky received a higher art education and is now a well-known graphic artist in Ukraine. Mr. Mykhailo told with sorrow how they brought his son to the camp for a visit. It seems twice. When he was a Pioneer, and then later a Komsomol member. The son even tried to re-educate his father. He probably had to. When he spoke about this, his eyes were in tears. Such heavy chains that stoic man bore on his shoulders.

During those long conversations, he advised me to be careful. Not to speak at the “seminars,” but only to listen to the “lectures.” Because the times were uncertain, they could add to your “term” for some trifle. And that happened very often in those zones. He didn't ask me to pass on or tell anything. Apparently, he realistically understood that he had already been forgotten and there was no one left there, and the rest who might still remember him were far away. He didn't talk about his participation in the OUN either. He said, if I have such a need to know, then let the “historians” tell me, and there were enough of them in the camp. He even made some ironic remarks about that.

I had less and less time left. There was no shortage of lecturers, including “historians.” And each tried to share their creative work. Some of my closest old-timer friends, like Vasyl Pidhorodetskyi and Roman Duzhynskyi, began to warn me against unauthoritative “professors,” because one shouldn't waste precious time. It was like that “shagreen skin.” For the uninitiated, it's hard to imagine, but it was really so. There was such an explosion of ideas and thoughts, such a period of camp liberalism “with a human face.” And I really didn't have enough time to listen to everyone who wanted to be heard. Opanas Zalyvakha often later recalled a precedent of relativity, that there was a man in the camp who sincerely considered his sentenced “term” too short. He said he wouldn't have time to cover the educational program. Listeners considered this a certain eccentricity. It might seem so after reading the memoirs of Vasyl Ovsiienko. Or even Mykhailo Kheyfets. But that's how it was then. But the “music didn't play for long.” And the camp regime with a somewhat human-like face didn't last long. In the 70s and 80s, a cooling began, right down to the regime of Siberian permafrost.

Concluding the stories about my meetings with M. M. Soroka, I want to emphasize once again that he stood firm and steady on his feet throughout all the long years in prison and camp. He was never once tempted by the illusory freedom in the “big zone,” never wrote any statements, and carried his cross without falling or stumbling, until his death.

One could write at length about others as well. But that would probably be too much. If you want to read more of the same, just say so. And I will add it in a reprint. That's a joke.

It seems that everyone has their own destiny, but the paths of those who were to be imprisoned until the end of Soviet power are generally similar. Arrests, torture, tribunals of three, torturous suffering in the Siberian GULAG archipelago, a brief breath of oxygen during the short thaw. And again, in the 70s and 80s, the Ural concentration camps, where many could no longer withstand the tortures of the regime and passed into the other world. This is a philosophy of life and struggle. As in the “big zone,” so in prisons or “small zones,” the irreconcilable always come into conflict with the authorities or the regime. And then it’s as God looks after each one.

So I will focus only on a few strokes to the portraits of some individuals.

Stepan Soroka was captured in the late 40s as a young man. He was a liaison. He had a weapon at the time of his arrest. He was given 25 years. He was obviously a clever lad. Through self-education, he acquired great knowledge of history, literature, and especially philosophy. Our conversations were very interesting. He was pleased to have an attentive listener, because no one there listened to him anymore. Over all those long years, each of those intellectuals had built his own concept and carried it around. It was in the 93rd zone that I learned that this state is called “gonit” (to run). That is, each one “runs” his own “movie” in his own way. I saw him at the second congress of the Rukh movement. He looked a bit lost. Apparently, he realized that his theoretical concepts were outdated. And then he disappeared. (Died in 1999. – Ed.).

There was a certain Belov from Leningrad. I don't remember what he was imprisoned for, whether as a dissident, or maybe he was from the group of plane “hijackers.” But he had a considerable term. He had a degree from Leningrad University. I think he was even a candidate of sciences. In short, a great erudite in poetry, literature, and the history of religion. It was interesting to listen to his lectures, and he was glad to have caught a listener with willing ears. But after two or three lectures during a walk around the stadium, one of the “well-wishers” calls me aside and says: “What are you talking to him for, he's a homosexual.” What a thing! A homosexual or a “pityukh” in the zone is like a black person in former America; you don't communicate with them in public.

I will also be brief about Yuliy Daniel. They brought him with a five-year sentence sometime in July 1966. He was arrested along with Sinyavsky for a book of pamphlets “This is Moscow Speaking...,” which they published abroad. He behaved independently, even proudly. Every Sunday, friends and his wife Larisa Bogoraz would come to the zone. He would climb onto the roof of a two-story barrack, and from a hill behind the fence, they would tell (shout) him all the news. Before my release, I had a couple of confidential conversations with him. He asked me to pass something to his wife. I stopped by and spent the night there. I even managed to read that seditious book. It was very interestingly written, I remember it well. I still tell the content of those stories. Here is a short one, “Hands.” Somewhere in a sanatorium in the south, a young man and an older, respectable man, whose hands are constantly trembling, are living in the same room. On one occasion, the young man asks him if he has been sick for a long time. And he hears a story about how, maybe forty years ago, in the twenties, he served in the OGPU and worked as an executioner. A job like any other, he had to shoot up to ten people per shift. One day he stood “at the barrier” and waited to see who they would bring out. A large, gray-haired old man with a long beard appears. He crosses himself, prays, and sends curses upon them. The executioner shoots, but he doesn't fall. He shoots again, and the man, with his hands raised, walks towards him. He fired about three more times and, out of fear, falls, losing consciousness. They treated him for a long time, and they seemed to have cured him, but God punished his hands. As it turned out, his friends had played a joke on him. They had given him a rifle with blank cartridges.

And “This is Moscow Speaking...” is a multi-plot, voluminous novella. One Sunday, the famous voice of the announcer Levitan broadcast a decree that a certain day in September was designated as a day of open murders. That is, anyone who wished could kill whomever they wanted without responsibility. It was late summer, with good weather. People were at their dachas, and not everyone could hear the announcement, as there were few portable radios back then. But rumors spread quickly. And everyone is waiting for confirmation of the announcement in “Pravda.” The authors present many variants of how different people are preparing for it, while still not having official confirmation... But you have to read it, because there are so many of those plots about individual fears, desires, and possibilities. Everyone is thinking about how to protect themselves or take advantage of such a decision by their dear party.

I have already written about Roman Duzhynskyi. I will now focus on two “strokes.” So Roman, or Veniamin, as he was also called in the camp, set about painting my portrait. He struggled for three days, but it just wasn't working out. We were both tired. So he calls Opanas Zalyvakha to help. Opanas didn't need to be asked twice and immediately got to work. To start, he says, let's take off the glasses and remove all the grayness. He only left a similar composition. And in about three hours, while reciting lines from Vasyl Symonenko's poetry, he finished the portrait. And it was a Sunday, and there were many “fans” watching. When Opanas allowed them to look, most were very surprised. Duzhynskyi and Pidhorodetskyi almost indignantly declared that he had “disfigured the man.” But the art critic Bohdan Horyn praised Opanas Zalyvakha's work as one of his best. This was Zalyvakha picking up a brush after an almost year-long forced break. He finished the background of the canvas, reciting: *“Хай палають хмари бурякові...”* And he put his signature. Duzhynskyi also did not delay in immortalizing his own signature. That portrait was exhibited in Lina Kostenko's home for a long time at her request.

So, Roman Duzhynskyi was released sometime in early October of that same year, 1966. He was given a fine welcome. He immediately wanted to visit Kaniv. And Lina Kostenko offered to accompany him by steamship. She was an ardent admirer of the prisoners of that time. So there was a certain piety towards him, also as an artist. After the trip, at lunch (because he had stopped at our place), Roman says: “Ivan, I'm getting married.” It's like in that joke. A man comes to a friend and says he wants to get married. The friend says: “So what's the problem, who's stopping you?” And he replies that no one is. So I ask, what's the matter, but why so suddenly, who is the bride? And he says that he declared his love for Lina. My wife and I were very taken aback by this. And somehow, little by little, we brought him back down to earth. Such things happen with creative people. And Lina Kostenko was a real beauty back then. Apparently, many men would have declared their love for her if they weren't afraid. Because she was unattainable, as if on a pedestal. We had such Amazons then, like Alla Horska and Lina Kostenko.

Here, speaking of which, I'll give one little episode. This is about the present-day Oksana Pakhlovska. She was a girl then, maybe in the sixth grade. She comes home from school one day with scratches and bruises. Her mother and grandmother are in despair: what happened? And Oksana proudly replied: “Nothing. I was fighting with my classmates because they were calling mom and me nationalists. So I taught them a lesson.” And she was a tall, strong girl. And she even says: “I want to be like you, mom.” That's how it is with genes.

And one more stroke to Lina's portrait, because where else will I have such an opportunity to tell it? She lived then, in 1966-67, with her mother and daughter near the Pecherskyi bridge. They lived, in fact, on her grandmother's pension. Ivan Svitlychnyi, who was her close friend, introduced us. And so one time, I secretly placed a sum of money, an average monthly salary, under a book for her. This was normal then—to help those whom the authorities did not allow to earn a living by their creativity. Later, many things changed in her life. She married the director of the Dovzhenko Film Studio. They said that her husband, Tsvirkunov, shielded her from her former friends. She stopped going out “among people.” And then the years of brutal KGB terror began. Almost all her friends were imprisoned for long years. And so somewhere in the late 90s, we accidentally met in the metro. More than 30 years had passed. We got off together at the “Universytet” station. She came up, greeted me, and began to look for something in her purse. She takes out some money and gives it to me, saying that she owes me a debt. I was bewildered and couldn't understand what she was talking about. She carefully reminded me of that incident, and with a logical explanation: “Only one of you Ivans could have left the money. And since Svitlychnyi had no money, because he himself was supported by his wife Lyolya, only Rusyn could have put the money there.” Such is female logic. After some of my refusals and after her threat to leave the money there somewhere, I had to take it. Such a detail of human memory.

Again, I've strayed too far from the camp meetings. Forgive me and read on.

Knuts Skujenieks. A Latvian poet and translator. He served eight years. He was released a little earlier than me and invited me to visit. He also took out his portrait by P. Zalyvakha. In the camp, he learned Ukrainian and translated Lesya Ukrainka. When I visited him in 1968, he gave me a collection of his translations of Lesya Ukrainka's lyrics, published in Riga in 1967. He showed me an almost ready-for-publication collection of translations of Vasyl Symonenko. He lived in his own house in the town of Salaspils. No one bothered him. Apparently, by that time in the Baltics, the “Russified foreigners” had all died out. It's in Ukraine that they are resilient and prolific.

Of the Muscovites, I only remember the Jews. They called themselves social democrats. Among them was an interesting fellow named Ilya Bromberg. Or a similar name. But he was a great “umnik” (know-it-all) on all topics. He knew everything and had his own opinion about everything. He often came to our clearing and listened attentively to our conversations. By the way, he learned Ukrainian in the camp. He was serving out his term. He was given 5 years for some speech near the Pushkin monument. He said that back then, that was a seditious place for them, where freethinkers gathered and where they were beaten and dispersed. He called that ruling gang salamanders. It would have been all fine, but he was a cripple, twisted and small in stature. They must have really gotten to him... And that was under Khrushchev. He was released a little earlier than me and asked me to visit him.

So, after visiting the Daniels and spending the night with them, I went to look for Ilya. I found the street and the house. A nice building and a clean entrance. But no one answered my rings. When I started knocking, a neighbor opened her door. She was an old woman, and also Jewish. She informed me that they were all at the dacha. She was apparently a friendly neighbor because she talked a lot about their affairs. She felt sorry for Ilya and said they had taken him “to recover.” And she finished by saying that we all told him and asked him “not to be too clever and not to stick out.”