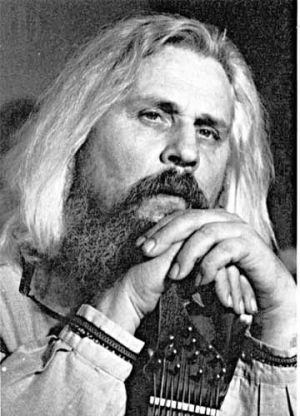

Vasyl Lytvyn. An Autobiographical Sketch

When a child becomes self-aware, they begin to define their belonging to a family, to a community, and later learn in which country they live and which people are their own.

We, the children of the post-war years, were shaped by school, because our parents toiled hard on the collective farm and had no time at all for our upbringing. Our mothers, barely sleeping through the short nights, would prepare food, sew and patch our clothes and shoes, and run back to work. But like most Ukrainians, both my father and mother sang while they worked. And so, starting with lullabies, the world of folk imagination—heroes, enemies, good and evil forces—subconsciously took shape in my soul, reinforced by the fairy tales that my parents, though rarely, told us. And then the school—categorically, irrefutably, and intrusively—molded us into Pioneers, Komsomol members, and, as the highest achievement, “party members.”

It was 1953, the year of preparations for a grandiose celebration: the reunification of Ukraine with Russia. Our teachers convinced us that if it weren’t for Russia and its fraternal help, Ukraine would have long ceased to exist. And the wisest of Ukrainians was Bohdan Khmelnytsky because he accomplished a great feat: he gave Ukraine over to the “hand” of Russia. Therefore, let us rejoice and praise him.

My father barely interfered in our upbringing, and only now do I realize why. Because he couldn’t, he was afraid: it turns out he thought differently than what we were told in school. One day I came home early. My father was sitting at the table, his head propped in his hands, and he was singing. When I listened to the words, I exclaimed in shock, “Dad! What are you singing?” My father flinched and looked at me—and such fear was reflected in his eyes that I froze. He was afraid of me, a Pioneer. A strong, healthy man was afraid of his own child! And a kaleidoscope of thoughts spun in my head: what if everything isn’t as they tell us in school? And this is what my father was singing:

“Ой Богдане, Богдане,

Занапастив неньку,

Неньку Україну!

Занапастив, ще й продав,

Бо в голові розуму

Та й не мав!”

I was 12 years old then. From that moment on, a rebellion against lies, injustice, and the violation of human consciousness began within me.

I was born on June 4, 1941, in the small village of Fedorivka in the Pishchanobridskyi district of the Kirovohrad region. My childhood was spent in poverty and hunger. A painful memory is etched in my mind. My mother is sick, lying in bed, and the brigade leader bursts in: “Why are you lying around like a lady? Who’s going to do your work for you? Get up, march to work!” Pale and exhausted, my mother overcomes her weakness and gets ready to go. We are crying, and the brigade leader cracks his whip menacingly. And a verse from a school textbook came to mind:

“У неділю пораненьку

Усі дзвони дзвонять:

Осавули, економи

На панщину гонять”

But isn’t what we have the same kind of serfdom?

Another snapshot from my childhood: my brother Mykola and I are gathering ears of grain into small sacks. And suddenly—a mounted watchman! We scatter in every direction, running headlong; because if he recognizes whose children we are, our parents face prison. This was 1947. We jump into a ravine where he can’t reach us with his horse. He shouts for us to come out. We are crying, pressed to the ground so he won’t recognize us. We got away with it: he was too lazy to get off his horse…

After finishing school, we escaped as if from hell. Kolkhoz workers were not given passports. We passed our exams and enrolled in the Krolevets Art and Technical School. They had to release us from the kolkhoz serfdom. In Krolevets, while singing in an amateur group, we encountered the bandura. Mykhailo Biloshapka taught us to play and guided us to the R. Glier Kyiv Music College. Fanatically believing that our lives were now forever bound to the bandura, my brother Mykola and I prepared for the entrance exams. Blood trickled from under our fingernails, but we played and played. Our incredible determination impressed the admissions committee, and… we were admitted to the college.

Here, in Kyiv, we met like-minded people and, without hesitation, plunged into a dangerous yet noble cause: fighting for the right of Ukrainians to be Ukrainians. We were all united by the inter-university student choir “Zhaivoronok” (Skylark). The boys and girls burned with a common desire: to revive and raise from oblivion our native song and language, to glorify the heroes of Ukraine, forgotten and dishonored. It is not surprising that all the choir members were under the surveillance of the KGB.

We performed our native songs in schools, workers’ dormitories, and on open-air stages in parks. Wherever young people gathered. And in the summer, during the holidays, we would journey through Shevchenko’s places, from village to village, giving concerts in each one. How warmly and sincerely people greeted us, how much gratitude was in their words to us!

But daily life was tightening around my throat like a noose. There was pressure, invisible to the outside eye: clashes with law enforcement on May 22 at the Taras Shevchenko monument, performance bans, and even threats from unknown individuals. My brother Mykola, at the invitation of friends, transferred to the Ternopil Music College. And I, having stayed in Kyiv, could not continue my studies. Even my teacher, Andriy Fedorovych Omelchenko, left the college: the atmosphere was not right! As he said goodbye, he warned me: “Don’t forget the times we live in. Know that they now make shit out of gold. And they try to make gold out of shit.” I understood what he meant much later. At the college, without his guiding presence, his guidance and advice, I felt like an orphan. I decided to leave, as it was also terribly difficult to survive financially; I had no financial support from anywhere, my scholarship was small, and there was no way to earn money anywhere.

I went to the Chernihiv Philharmonic and was accepted into the bandurist ensemble. After the very first concerts, I was horrified: the ensemble was filled with “artists” who had neither a musical ear nor a voice and had never played the bandura; they just moved their hands, pretending to play, without even touching the strings. It was then that I understood my teacher: they were making shit out of Ukrainian songs and the bandura—pure gold—and trying to present inept “artists” as gold. Our performances provoked disgust and a reluctance to see or hear us. Once, after a concert, people even wanted to beat us up as hacks. The administration paid no attention to my remarks. A soloist who could more or less sing left the ensemble. To shut me up, they put me in his place. But this didn’t change the situation, though I tried as best I could.

By that time, my brother Mykola had graduated from the Ternopil Music College. I called him to join me, and we were allowed to perform as a duet. But the ensemble still had singers who shouldn’t have been allowed anywhere near a bandura, let alone a stage. My soul could not bear it: I told the artistic director, Leonid Pashan, everything I thought: “You are using state money to do a treacherous thing for Ukraine: you are disgracing the Ukrainian song, the bandura. How do you select your artists? Based on what qualities? They can neither play nor sing. The banduras have ropes instead of strings. Your pop ensembles are provided with everything: talented artists and instruments. No, I no longer want to take part in this farce. Whose will you are carrying out, I don’t know, but I know for a fact that you are doing a dark deed for Ukraine and the prestige of its culture!”

We quit and went with my brother to our parents. We prepared a repertoire and, as a duet, went to the Kyiv Philharmonic to be heard, intending to get a job there. We were greeted warmly; they said they knew our duet, but the director would be in tomorrow, so we should come for an audition. But the circle was already tightening around nationally conscious Ukrainians. When we came back “tomorrow,” no one paid us any mind; they pretended not to know us and not to want to know us.

A day later, my brother was arrested, right on the street. For his participation in a nationalist circle in Ternopil. I was told that he was being held as a witness. For two long months, I went every day and demanded that they either release my brother or take me too, because I thought and felt the same way he did.

When my brother returned, he told me that they had tried to pressure him into becoming an informer and ordered him not to tell even his own brother about it. He refused. Then they told him: “From now on, the ground will burn under your and your brother’s feet; everything will fall from your hands. You won’t find work anywhere!”

Wherever we turned, they would first make promises and tell us to come back tomorrow. And then they would turn us away. We went to Ternopil, where we had previously been invited, but the administrator, while talking to us, kept dialing a number, saying a few words, listening, and then throwing up his hands and telling us to come back in a few days. I peeked at the number he was dialing and called it from a pay phone. When they answered, I identified myself and said: “If I smash a store window right now or do something else of the sort, will they take us to the police and feed us there? Because my brother and I can’t honestly earn money for food because of you.”

They offered to meet with me. The substance of the conversation is clear without explanation. But as we parted, I was told: “Go and work. But know that you will be watched at all times: think about where and what you sing.” We were hired by the Ternopil Philharmonic. We sang without thinking about the surveillance, choosing songs that spoke to the heart and even composing our own to words that moved our souls. We worked there for only three months. And then the military enlistment office summoned me for a medical commission. I already had my military ID, which stated that I was unfit for army service due to my health. The new medical commission delivered its verdict: “Fit for combat duty.” They responded to my brother’s petition: “Let him be thankful we’re not sending him to the far north, but that he will serve in Ukraine.”

Service in a mortar battery was hard. The physical strain caused a stomach ulcer to open up. My superiors diligently carried out their task: to humiliate me, to break me, to beat the unnecessary “thoughts” out of my head. They wanted me to beg and whimper, to repent and make promises. But I found the strength to remain myself until I was discharged and sent home for family reasons.

I worked back in my native Kirovohrad region, in a locomotive depot. My friends from Kyiv did not forget me. With the help of Alla Horska, my family and I went to work in the village of Ivankiv and at the Boryspil House of Culture.

In 1968, the Music and Choral Society initiated the creation of an orchestra of Ukrainian folk instruments. I was invited for an audition and offered a job. They also invited my brother Mykola to the orchestra. In 1969, the Society organized a large kobzar concert at the Opera Theater. It was a major event for Ukraine, as there had been no kobzar performances since 1939. The echo of that concert resounded throughout Ukraine. Interestingly, when the concert program was being approved by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, some clerk, upon reaching my name, read: “Oy polety, halko” (Oh, Fly, Jackdaw), “Oy, ne puhay, puhachenku” (Oh, Don’t Frighten, Little Owl) and said with a laugh, “About birdies? Let him sing!” This conversation was relayed to me by the secretary of the Music and Choral Society, who had taken the repertoire for approval. And at the theater, when I sang “Oy, polety, halko,” there was a storm of applause, with shouts of “Slava!” (Glory!). The next song was met with the same reception. These songs were composed during the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich; no one sang them, but Ukraine’s pain for its defenders resonates in them to this day.

While working in the orchestra, my brother and I revived our duet. The public received us warmly. At one concert, after we performed the song “Tam, u stepu” (There, in the Steppe), with lyrics by Vasyl Symonenko and music we composed ourselves, the hall erupted in applause and shouts of “Slava!” The same happened at the Philharmonic after we performed the song “Marsh Bohdana Khmelnytskoho” (Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s March), with music we composed to lyrics by Stepan Rudansky. The orchestra’s performances were met with thunderous applause both in Ukraine and abroad. But the seventies were also a difficult time for Ukraine. Censorship touched the orchestra’s repertoire. Our duet was almost never allowed on stage, except for rare occasions. And then the orchestra’s director, Yuriy Voloshyn, suggested to me: “Submit your resignation of your own accord. Otherwise, we’ll fire you for cause, and you won’t be able to get a job anywhere.” My wife had already been “asked” to leave the Molod publishing house, so at that time our family was living in the village of Hrebeni in the Kaharlyk district, where my wife’s relatives lived. We live here to this day.

It was very difficult to find a job. We were bluntly told: “You are nationalists.” People didn’t understand what that meant, but they were terrified. We worked wherever we could: my wife and I went to the fields to pick beets, we mowed hay, we worked on silage. Eventually, we found a place in the village house of culture. We were under constant supervision from the village council, with checks, audits, nit-picking, and pressure at every turn, like: “How much longer will we have that bandura that everyone is sick of, and those Ukrainian folk songs in concerts? Sing something a human can understand!” But the people themselves thanked us for our songs, for the bandura, for our plays (we staged almost all of the Ukrainian classics on the village stage).

We composed songs, wrote poetry. Friends from Kyiv, Lviv, and Ternopil visited us—everyone whom fate had brought into our lives and who had not forgotten whose sons and daughters we were, and of which parents.

In 1989, the idea of creating a kobzar school matured. With the support of Borys Oliynyk, and with the consent and active efforts of H. M. Ivanova and her husband, a kobzar school was founded in the village of Stritivka.

So many nets and obstacles were torn through to have the school recognized as an educational institution that would train knights of folk song, champions of the kobzar revival. The shackles placed on our native language and song for centuries have not been broken even to this day. The beauty and power of the folk song must constantly be revealed to the world. And so, the kobzar school has already prepared 153 graduates. The boys have gone out across Ukraine with banduras in their hands and songs in their souls and on their lips. Today, I have concert and lecture programs on patriotic themes, with which I perform, by invitation, in various cities and villages, mainly in educational institutions.

Prepared by V. Ovsienko.