Andriy OKHRYMOVYCH

FROM THE COHORT OF THE SIXTIERS

“Suchasnist,” no. 12 (380), 1992. – December. – pp. 129–136.

On June 19, 1992, Veniamin Kushnir passed away. He was one of the most cultured artists in the broad sense of the word, a quintessential Sixtier—one of those who did not betray their conscience, did not conform, did not forsake their ideals. When the wave of repressions and terror of the 1970s stifled cultural and artistic life in Ukraine, he, like many other creative people, withdrew into solitude. This marked the beginning of the artist’s drama in the face of a cruel, deaf-mute era that, for him, despite all the perestroikas and slogans, lasted until the final day of his life. The Union of Artists, led by established opportunists, having lost hope of luring the artist to their camp, began to hound him with expertise. Here is a typical case. When Kushnir submitted his profound and plastically flawless canvas “Dovbush” to the artistic council in 1982, it was rejected with an utterly idiotic argument: “And who are they shooting at?” Whether due to circumstances or inertia, the situation has changed little even today.

The purpose of this publication is to remind the general public of an outstanding artist and citizen who could have said of himself with a clear conscience: “We just walked; we have not a grain of falsehood behind us.”

Kushnir was born on January 7, 1926, in the village of Rudka, Kamianets-Podilskyi Raion.

He began drawing in early childhood. At first, he would copy from books; later, during the war, he met a professional artist. The artist took him along to paint plein air, giving him paints and brushes. Some works from that time have survived. They testify to the young man’s considerable natural talent.

His path into art was rather convoluted. His father was a tailor, so he sent his son to be trained in a tailor's workshop. Perhaps this is the origin of the artist’s solidly crafted compositions. Whatever the case, Kushnir could always sew something for himself. He often joked, “If I had become a tailor, I would have been a great man.”

His tailoring career was cut short by a call-up to the Soviet army, where they tried to make a military paramedic out of him. After six months, having escaped the heroic ranks by hook or by crook, he tried his hand at the physics department of Kyiv State University, then enrolled in the polytechnic institute. He only truly found his footing at the Lviv Art Institute. He often recalled his classmates and the dormitory where twenty people lived in a single room.

From literature of various genres, we know about the difficult lives of artists. But it’s unlikely that Van Gogh, sitting in some Parisian café, had to think something like, “…hmm, Cézanne, I wonder if he’s a snitch…” Among the twenty residents of the dormitory room, there was bound to be one; there couldn’t not be. This fact alone constrained movement and hindered normal development. The generation was young, unfamiliar; after getting acquainted, they resorted to Aesopian language. Debates, in which truth should be born, rarely went beyond the permitted framework… But Lviv, despite everything, retained its prerogative as the spiritual Piedmont of Ukraine. This was all the more true since the bursts of insurgent machine guns could still be heard in the surrounding forests. Painting in the mountains could cost one dearly back then. Yet, despite everything, he and a highlander friend traveled through villages, painted a lot, and took part in Hutsul festivities. At one of them, he witnessed a fight: brutal, terrible, but interesting for its unexpected reconciliation and ritualistic arkan dance. It was here, in the Carpathians, that he sought and found the spiritual roots of the people. In their clothing, dialect, customs, architecture, icon painting… Like an archaeologist, he reconstructed a whole from shards, and in that whole, he observed the cultural body of Kyivan Rus and saw the continuity of the national existence, which, depending on circumstances, either subsides or manifests with new strength, but is never completely broken. The proud Hutsuls, whom a dark, terrible power had turned into collective farmers, suddenly feeling the call of their blood, tear off the masks of daily routine and, woven into a militant arkan, are frozen on the master’s canvas, becoming a metaphor, a captured essence, their very selves.

For a moment, it seemed to him that passing exams on the history of the Party was nothing but a nightmare, and reality was right here: the Rus of Danylo Halytskyi. But the dream passed, and he was once again wandering through a rainy Lviv, trying not to look at the bloody banners of communist slogans.

In Lviv, Kushnir was formed as an artist and a citizen. Despite the discomfort of the political realities, a national cultural environment was preserved there, the Ukrainian language dominated, and the very architecture of the old city awakened thought with its every curve, cultivating aesthetic sensibility. It was there that he felt the full weight of responsibility for the nation’s fate. The phrase “if not me, then who?” became his credo.

As an artist, he evolved within the framework of the Lviv realist school, whose adepts were Manastyrsky and Trush. The influence of the latter is palpable in Kushnir’s early works. Later he would develop his own unique style, but for now, with the collar of his old coat turned up, he attended exhibitions, often visited the opera, but more often the freight station, where, unloading railcars, he supplemented his meager student budget.

In 1953, after brilliantly completing his diploma work, “Bohdan Khmelnytsky with His Army,” Kushnir left Lviv. The reason: they wouldn't grant him a residence permit. At the invitation of a fellow student, he went to Dnipropetrovsk, where for two years he taught at an art school and actively participated in exhibitions. In 1954, he joined the Union of Artists. After moving to Kyiv, he wandered for a long time without an apartment, without a studio. He had just enough money for a pirozhok and some soda water with syrup. But, be that as it in may, youth, energy, and self-belief compensated for all hardships.

“He was back then,” recalls Halyna Petrivna Kushnir, the artist’s wife, “energetic, cheerful, handsome. He had many friends. He loved music, especially classical. He often attended the philharmonic, open-air concerts. And he always painted to music.”

From 1959, Kushnir worked in a collective studio in the refectory of the Lavra. It was then that he painted “Trembita,” “Raftsmen,” “Lumberjacks,” and “Red Poppies.” The language of these canvases is symbolic, with deep subtext; they can be seen both as a manifestation of an archetype and as a conscious immersion into the depths of tradition. Analyzing Kushnir’s works from this perspective, let us recall that, according to Jung, creativity consists in reproducing impressions repressed in the archaic epoch and is essentially reduced to reproductive activity. A collective (nation), through an individual creative personality, reproduces its aesthetic, moral, and religious experience, but now on the level of symbol and metaphor. We see something similar in “Raftsmen,” which reproduces one of the most ancient Hutsul occupations. There is not a single detail that would tie the action to a specific time. The river, on which the raftsmen float logs, is time itself. The painting, in addition to the multi-layered semantics of its imagery, has a high degree of plastic self-sufficiency. Thanks to its internal expression and tightly-knit composition, it is perceived, despite its traditional execution, as a thoroughly modern piece.

But Kushnir’s crowning achievement of this period was “Trembita.” The perspective, the diagonals of the trembitas, the anxious, expressively painted sky, the color palette, and the three-figure composition (a deeply symbolic number the artist uses very often) achieve perfect harmony here. The canvas evokes direct associations with Shevchenko’s “…and sharpen the axe well, and then set about to awaken…” It is strange, but despite the seditious content, it was reproduced and circulated on officially published postcards.

Besides a shared hatred, he is akin to Shevchenko in his tender attitude toward women, the cult of the Madonna. Hence, perhaps, the soft lyricism of “Red Poppies.” This piece suggests a lost paradise of soulful human relationships and harmonious coexistence with nature. Kushnir perceived life as a very delicate and tender substance. “It is a celebration in the Universe,” he often repeated.

Overall, the 1960s were rich in impressions, friendships, and proposals. Official artists tried to lure him into their camp, suggesting he paint on so-called contemporary themes. “Then you would quickly rise to the top,” they cajoled. But other peaks rose before him, on which the figures of Gogol, Shevchenko, and Michelangelo loomed… The high bar he set excluded any self-indulgence. He painted a lot, read, and discovered new literary names (thankfully, the political winds had warmed, and some things were being published). His desk books were the Bible, the Kobzar, and Skovoroda. His circle of friends included Symonenko, Sverstiuk, Zalyvakha, Svitlychny, Horska, Taniuk… Debates, conversations, at the center of which were the past, present, and future of Ukraine.

In 1962, Kushnir became one of the most active members of the Club of Creative Youth. At brilliantly organized events, he, along with others, promoted Ukrainian art, forgotten names, and the classics. Well-read, with a philosophical mind, he had original and profound judgments on everything. These years also brought his greatest material prosperity. First, he received a studio on Filatov Street, and later a one-room “Khrushchevka” on Dashavska Street. There was always someone in his studio, always a debate in which, along with truth, a new person was often born. He won over many for Ukrainian art by awakening their national gene. Kushnir played a significant role in the spiritual evolution of the outstanding Ukrainian artist Opanas Zalyvakha, who was initially in the orbit of Russian culture. A deep mind, talent, and innate aristocratism made Kushnir one of the most influential ideologists of the Sixtier movement.

On December 14, 1963, Symonenko died. At the funeral was the entire cream of the national movement. And the KGB agents were there too, taking photographs, recording speeches. The first signs of surveillance appeared. In their studio and apartment, the Kushnirs found unfamiliar cigarette butts, and unexpected friends with ultra-radical talk began to hang around. Meanwhile, the Kremlin leader, having descended into senility, banged his shoe on the UN podium, cursed at writers, planted corn, and his bushy-eyebrowed successor jailed “nationalists,” thus creating his own version of the Internationale behind barbed wire.

“The first arrests took place in September of '65,” recalls Halyna Petrivna. “We were in the Carpathians then. On the way, we stopped to see Zalyvakha. We were guests together at the artist Mykhailo Figol’s house, where, as it later turned out, a KGB agent photographed us through the window. We returned from the Carpathians via Ivano-Frankivsk. We went to Zalyvakha’s—the door was sealed. We asked the neighbors—no one wanted to say anything. We went to the building administration—‘contact the police,’ and only Figol told us that Opanas had been arrested. That was when they also arrested the Horyns and Osadchy. All of this somehow broke Veniamin. ‘Why was Opanas arrested, and not me,’ he worried.”

The “humanism” of the masters of life, clearly underpinned by refined sadism, hit its mark. Kushnir found himself in an ambiguous position. He, who considered himself the most guilty before the authorities, was “free,” while his friends were—there. This was enough for him to seriously consider suicide.

Left in the larger “zone,” Kushnir was doomed to crippled communication with others like himself, who were under surveillance. Those who had broken would cross to the other side of the street upon meeting him. The extreme situation put everything in its place. It threw the talkative pseudo-heroes into a pit of shame and self-recrimination, packed the real heroes behind bars, and confined Kushnir to the enclosed space of his studio, under whose windows spies regularly kept watch.

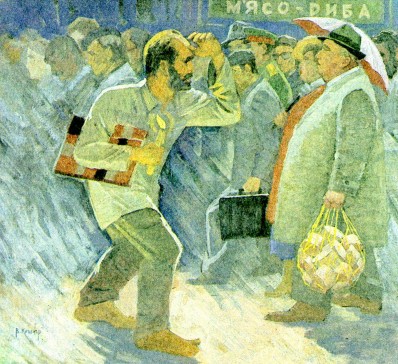

Around him scurried marionettes, characters from Vynnychuk’s “Shchurohrad,” with their shopping bags in hand and sausage-themed topics on their tongues. “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” Goya inscribed on his “Caprichos.” Kushnir, for his part, painted “Violated Ukraine.” He transferred the greedy and lustful mob to canvas, this time in a more abstract form. Interlopers and turncoats of all ages, in a rectangular, aggressive mass, descend upon a defenseless, volumetrically rendered woman—Ukraine. The dominance of black, the expressiveness of broken lines, and the brutal avalanche of faces leave almost no hope and give an exhaustive picture of the artist's state of mind during that difficult time. An sketch for a self-portrait from the same period is consonant with this canvas. The artist depicts himself against a backdrop of a human stream laden with food and toilet paper. In fact, these are no longer people, but walking stomachs. Barefoot, with his shirt untucked, he shields the delicate flame of a candle with his left palm. A parallel with Diogenes, who searched for a man in broad daylight in Athens with a lantern in his hand. “Kobza” also appeared at that time, one of Kushnir’s best works. The tightly sculpted figure of the kobzar in the foreground and the almost ghostly specter of the Cossack cavalry, flattened in a gust and painted in red, create a sense of the action’s irreality, a mystical effect. It brings to mind the horses in Serhiy Paradzhanov’s “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors”—perhaps they appeared not without Kushnir’s influence, as the film director used to visit his studio.

A natural thinker, Kushnir could not bypass the image of Skovoroda. For almost a decade, he worked on variants of the painting. When the final version was found and transferred to canvas, an incurable illness struck the master down. We are left only with the composition on canvas and the first underpainting. Kushnir approaches the theme of Shevchenko, who is always relevant, always on the cutting edge, in an original way. Dressed in the white toga of a patrician, he warns “The dead, and the living, and the yet unborn…” against plebeianism. A people without an aristocracy of spirit is nothing more than a common crowd.

While working intensively on his canvases, Kushnir did not forget his friends. He corresponded with them, sent books, and thought about how he could see them. Finally, having wrangled a business trip to Moscow from the Union, he disregarded his own safety and went to a Mordovian camp, just to exchange a few words with the boys through the barbed wire. He was detained there, searched, and released with a “tail.” In Moscow, “archangels” pursued the artist: “Citizen in the cap, stop!” Shaking off his pursuers, he safely returned to Kyiv. His luck, however, was relative. The screw, already tight, was given a final turn. He was barred from exhibitions, thereby cornering him financially. The Union, if it bought his paintings at all, tried to stuff them as far away from public view as possible. Thus, three canvases—“Mothers,” “The Bride,” and “Holiday”—ended up: the first in the Zolotonosha vocational school, where it was used to cover windows during repairs and later tossed into the attic; the second in the Onufriivka district party committee office, under the convoy of numerous, clumsily daubed leaders; the third in a village club in the Kamianets-Podilskyi region. All of them are in need of restoration. Unfortunately, the paintings were only recovered after the artist’s death.

The obstruction, despite perestroika, continued as long as the Lopukhovs and Shatalins held sway in the Union. And this had its own, so to speak, logic; the artist was internally prepared for it, whereas contacts with the idealized Western world remained uncharted territory. And so, two years ago, a certain respectable man visited the studio—an exhibition organizer, a diversified businessman or, as the cheated artists call him, a multi-profile swindler, a Ukrainian from Chicago. After talking with Kushnir and leaving a receipt, he took with him nine first-class canvases. Neither the promised money, nor the businessman, nor the paintings have been seen since. Every family, as they say, has its black sheep.

Unfortunately, the artist had no solo exhibitions during his lifetime.

And without the artist’s best works collected together, at least in a well-published album, one can hardly hope for a definitive understanding of this extraordinary figure in Ukrainian art.

One wants to believe that, in time, a state program for the revival and protection of Ukrainian culture will be implemented. Or, at the very least, that cultured people with means will appear, Ukrainian Tretyakovs of our own, with whose help—if our little calf, God willing, ever manages to eat the wolf—something like a national gallery will grow up among us, where Arkhypenko, and Malevich, who was pilfered by our “elder brother,” and the Sixtier artists, among whom Kushnir is a star of no small magnitude, would find their rightful place.