Refat Shakir-Aliev

Memories of my Teacher

After a forty-year hiatus, I once again encountered the unforgettable Fyodor Fyodorovich Detenhof (“Fefe,” as his colleagues called him amongst themselves), who was my first teacher of psychiatry. The unexpected encounter began when my friend from Philadelphia, Iosif Slobodskoy, with whom I worked side-by-side for a quarter of a century at the Tashkent Psychiatric Hospital, sent me a biographical article about Professor Detenhof, published in the “Independent Psychiatric Journal” for 2009.

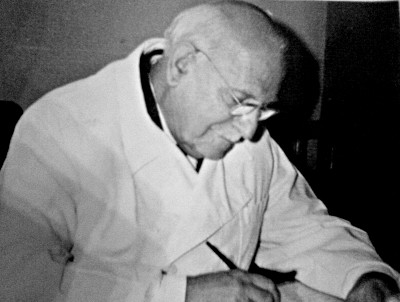

The intelligent and noble face of the man who once influenced my choice of specialty immediately caught my eye and stirred a wave of pleasantly aching nostalgia. I remembered how, as a student, I listened with rapt attention to his lectures on psychiatry, and I especially loved how the professor, with his handsome French accent, would pronounce the term “déjà vu.” The author of the article turned out to be Professor Sh. Magzumova, which is flattering for me, as she is a student of mine whose doctoral dissertation I had the honor of supervising.

The article was accompanied by an afterword by Yu. S. Savenko, the chief editor of that journal. It reported on an unprecedented event in Soviet psychiatry: in 1969, the Tashkent forensic psychiatric expert commission, responsible for the examination of the prominent human rights activist General Pyotr Grigorenko, refused to bow to the authorities and instead delivered a verdict dictated by medical duty and civic conscience. The commission was headed by Professor F. F. Detenhof.

F. F. Detenhof was descended from Russified Dutchmen. As he himself reported, his father was a famous perfumer in Moscow. With his noble appearance, refined manners, cultivated way of interacting with people, and broad erudition, which was evident in his lectures and speeches, he served as a model of a true (not ostentatious) professor of the old school.

My boss Sh. A. Murtalibov, then an associate professor in the psychiatry department, and I visited Fyodor Fyodorovich in the hospital before his death. He looked quite cheerful and told us the story of the suicide of the outstanding psychiatrist Artur Kronfeld, who had fled to the USSR when the Nazis came to power in Germany. Kronfeld had compelling reasons to do so. Firstly, because he was Jewish. But the main reason was that he had diagnosed none other than Hitler himself with psychopathy when Hitler, still a little-known politician, was undergoing a forensic psychiatric examination. Stalin allowed Kronfeld to remain in Moscow—he was too famous a figure in world science, and Stalin understood that—but his young colleague E. Sternberg, who had also previously fled from the Nazis to the USSR and later, as I learned, helped A. Kronfeld to emigrate, was repressed.

When the fascists approached Moscow, Hitler personally ordered Kronfeld to be brought to him, apparently to continue their discussion on the topics of psychiatric diagnosis. This was a time of panicked evacuation from Moscow (I know how it went from my mother, who was a student at the Moscow Medical Institute at the time). The elderly Kronfeld was entrusted to the care of a rather well-known Soviet psychiatrist named Shmaryan (I remembered the name and later learned it was not of Armenian origin), but the latter, apparently, had other things on his mind than Kronfeld. As did the rest of his colleagues. The unfortunate Kronfeld, left alone and perfectly aware of how his scientific discussion with his former patient would end, decided not to tempt fate and committed suicide.

From Fyodor Fyodorovich, I also first heard the story of the mysterious death of another outstanding psychoneurologist, Bekhterev, who had the carelessness to orally diagnose Joseph Stalin with “paranoia.” This story was later written about in the “Literaturnaya Gazeta” during the era of Gorbachev's perestroika.

Such are the amazing parallels found in the biographies of outstanding people! Incidentally, A. Kronfeld, along with E. Bleuler and E. Kretschmer, was one of the authors of the concept of the schizophrenic spectrum of disorders, a direct product of which was the diagnosis of “sluggish schizophrenia.” This diagnosis, by an irony of fate, was later widely used by Soviet psychiatrists for political purposes.

I have dwelled in detail on the content of what Fyodor Fyodorovich told us not only because it was my last “living” conversation with him and for that reason is etched in my memory, but also because this episode also characterizes the professor as an open and independent man. To recount these stories—though not criminal, they were far from harmless from the perspective of the relevant authorities—in the KGB-haunted 1970s, and to a greenhorn like me at that, is something a banal and cautious philistine would never have allowed himself to do.

As for A. Kronfeld's student, Erich Yakovlevich Sternberg, he was rehabilitated after Stalin's death, returned to Moscow, defended his master's and doctoral dissertations within a year, and worked for many years at the Institute of Psychiatry of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences. He was, undoubtedly, the most erudite of Soviet psychiatrists, regularly publishing reviews on scientific problems in the leading journals.

There is information that it was E. Sternberg whom the lawyer S. V. Kalistratova—about whom P. Grigorenko writes in his book “You Only Meet Rats in the Underground”—demanded be included in the forensic psychiatric commission to examine the disgraced general. This fact attests that E. Sternberg had a reputation as a highly qualified specialist and, more importantly, a decent man. Although I had never heard of E. Sternberg having any connection to forensic psychiatry. Then again, there was much I didn't know. I am personally proud that Erich Yakovlevich was the official reviewer for my dissertation and gave it a positive review. I was fortunate enough to interact with this exceptionally intelligent man.

Let us, however, return to Professor Detenhof. His personality cannot be painted with a single brush. It was quite complex and contradictory, like the very era that fell to his lot. I by no means take on the role of his biographer and base my account only on my subjective impressions, drawn from personal interaction with Fyodor Fyodorovich.

First of all, about his worldview or, as it was then called, his ideological orientation. Once, while still a student, I asked Fyodor Fyodorovich to look at a manuscript containing a philosophical essay on the problem of intuition by my friend Sasha Tyan and some quotes from Nietzsche with my own commentaries. The latter were youthfully enthusiastic and romantic, and I can reproduce little of them now. And I never did understand Nietzsche's teachings, but his style of expression made a strong impression on me at the time.

The professor, returning my notebook, said that he had written his opinion in it, and to a curious associate professor from the department, he replied, “Paralogic!” With that, he raised his index finger meaningfully. I did not sense any mockery. Burning with curiosity, I opened the treasured notebook. There, under my comments on Nietzsche, was written in a neat hand: “This is what ideological immaturity leads to!” What followed was a lengthy exhortation to study dialectical materialism. You can imagine the look on my face.

In another episode, he again demonstrated his ideological prowess. After my report on the then-sensational experiments of the Spanish neurophysiologist Delgado, the professor commented on them with sarcasm and delivered a whole lecture on the harm of subjective idealism, on which, in his opinion, Delgado's research was based. He also seemed to mention Pavlov's teachings, as he did on more than one occasion. I understood little of his admonitions at the time, but a certain feeling remained. And my impression of the professor formed as that of an ardent materialist of the Soviet school.

Soon after Detenhof's death, by a twist of fate, I ended up in his home and became acquainted with his manuscripts. His vast library (like the rest of his quite considerable inheritance) had by this time been thoroughly plundered by unknown people, but his manuscripts and watercolors—he was a decent painter—were left behind, apparently deemed to be of no value. And it was in these manuscripts that the real Detenhof was suddenly revealed to me.

I have no basis to claim he was a secret Freudian. But, as I understood it, the sexual sphere was at the center of his scientific interests. And this was a time when Freud's teachings, like everything from the West, were declared ideologically alien, if not outright banned. And here, in the notebooks of the mentor I revered, written in that now-familiar hand, were excerpts from the works of Western psychologists, analyses of his own clinical observations taking into account the patients' state of sexual development, and more in the same vein. And not a word about Pavlov's teachings, nor about dialectical materialism. All of this was in stark contrast to the psychiatry that was delivered to us in the periphery by the S. S. Korsakov Journal.

I remembered that when consulting patients, the professor, as a rule, paid attention to the sexual sphere, although he did not touch upon it in his conclusions. One episode is seared into my memory: after manually examining the genitals of a boy-patient, the professor pronounced, “Not ample, but sufficient.” But I cannot recall an instance where the results of such examinations significantly influenced the course of a patient's treatment. I do not rule out that the professor made some therapeutic adjustments, but he did not draw his colleagues' attention to them.

Apparently, most of the intelligentsia lived a similar double life back then: one life—the official one, the other—for the soul. There were few individuals like Pyotr Grigorenko, who openly expressed their protest against the machine of spiritual violence. But even they had to break through a cocoon of their own false convictions, instilled by the state ideology. On the other side of the barricades, however, as at all times, stood the serried ranks of figures who had accepted the rules of the game proposed by the state and, to the best of their abilities, used them for their own ends. To what extent they were sincere in their belief that they were doing the “right” thing, I cannot judge. More likely, many of them simply didn't think about it, leaving the luxury of thinking to the state and relying completely on its rightness.

And even they, those playing on the side of the authorities, were very different. Take, for example, two pillars of Soviet psychiatry at the time, A. Snezhnevsky and G. Morozov. Two academicians, two heads of the largest research institutions in the Soviet Union, two figures lavished with favor by the authorities, who unquestioningly carried out state orders... The similarities end there.

Snezhnevsky was an intellectual, the creator of his own clinical concept of the forms of schizophrenia's progression. Thanks to his authority, colossal scientific resources were involved in the development of this concept for many years. However, a great deal of intellectual and financial resources was spent in vain. As I became convinced while working as a psychiatrist in Australia, where different, higher-quality medications are used to treat psychoses, and where the course of schizophrenia is therefore noticeably different from what was observed in the USSR, Snezhnevsky's classification does not work.

But be that as it may, Snezhnevsky was a scholar of major caliber, and in this he was fundamentally different from G. Morozov, whose tongue-tied speeches at scientific congresses and symposia, where he was forced to speak as the invariable chairman of the presidiums, were legendary. I remember how one of my colleagues, who completed his dissertation at the Serbsky Institute headed by G. Morozov and was familiar with the scientific kitchen there, loved to repeat, “I want to be like Georgy Vasilyevich. He never wrote a single article himself and became an academician.” V. Morozov, known among psychiatrists for his sharp tongue, would praise his academician namesake: “Gosha is smart. He knows his place. Another man might not understand psychiatry, but he’ll jump into an argument. But Gosha doesn’t understand, and he doesn’t jump in.” Or another witticism from V. Morozov: “Georgy has a big enterprise, and he manages it well. He should be the director of a state farm, but he latched onto a scientific institute.”

But many people capable of sober thought, one of whom was Professor Detenhof, did not wish to take any side on the barricades and kept, as much as possible, out of ideological battles. And I understand these people well. They secretly sympathized with the minority that openly expressed its protest, but also tried not to expose themselves to ideological labels—the favorite weapon of the “all-powerful” majority—which could become a “wolf’s ticket” for their professional careers, at a minimum.

But life is life, and from time to time it confronted these people with a choice: conscience or well-being, medical duty or the “duty” of a Soviet citizen. It was precisely such a situation that F. F. Detenhof found himself in when conducting the examination of P. Grigorenko. I would very much like to know what the professor felt and experienced during the examination, and what motives influenced his conclusion, which became a symbol of medical conscience. But alas... one can only speculate.

Perhaps one motive, if not the main one, then at least an important and general one, for rejecting the previous diagnosis made by Snezhnevsky and Lunts, could be that Detenhof had an organic aversion to the psychiatry that was being created by Snezhnevsky and his circle. This was evident, if only from the fact that he sometimes allowed himself to poke fun at the concept of the forms of schizophrenia, Snezhnevsky's brainchild, and held fast to the old Kraepelinian classification to the very end. His young colleagues, myself included, attributed this to the conservatism of an aging professor. But, as time has shown, he was right.

And it wasn't just about the new classification of schizophrenia. Comparing the scientific publications of the 1920s and 1930s (when, by the way, Detenhof was formed as a scholar) with the later works of Soviet psychiatrists in the 1960s-80s, I myself felt that Soviet psychiatry had become somehow sterile and formulaic. An ideological schema dominated it, and the immediacy of observation and living thought—that which gives psychiatry its appealing romanticism—had vanished. What remained was a dead structure, but the patient himself was no longer there. For that matter, it was not only psychiatry that had become like this; the ideology itself was depersonalized and dehumanized.

Of course, Detenhof’s rejection of the Soviet psychiatry of his time was more of a backdrop than the decisive motive for his decision. In such situations, the main factor was and remains conscience. The conscience of a doctor and a human being. And civil courage. In F. F. Detenhof, these were at their height. While in no way diminishing the importance of the absentee examinations conducted later by S. Gluzman and the American psychiatrists A. Stone and W. Reich, which also found P. Grigorenko to be mentally sound, I must nevertheless say that the conclusion of the Tashkent commission, headed by Professor F. F. Detenhof, produces a much stronger impression and has, I am not afraid to say, historical significance.

I have two reasons for this assertion. Firstly, a precedent was set in Tashkent: for the first time in the history of forensic psychiatry, a challenge was thrown down to the authorities who use psychiatry for their political ends. This is also noted in Yu. S. Savenko's afterword. Secondly, there is a difference between a conclusion reached in absentia by a participant in the human rights movement or, even more so, by foreign specialists with predetermined attitudes and objectives, and one reached by doctors who are not swayed by any other considerations than the pursuit of truth—that is, delivering a verdict that corresponds to reality. And I consider it a failing on the part of the authors of the Wikipedia article on P. Grigorenko that, while naming S. Gluzman and the American doctors, they for some reason did not include the names of the doctors of the Tashkent commission, who performed a medical and civic feat.

Speaking of civil courage, which P. Grigorenko writes about when mentioning the writer A. Kosterin, I do not know if the doctors A. M. Slavgorodskaya and I. L. Smirnova, whom I knew personally for many years, were fully aware of the possible unpleasant consequences for them, but I have no doubt that Fyodor Fyodorovich clearly understood what he was getting into by changing the diagnosis of the capital's luminaries. What role was played in the decision by E. B. Kogan, a doctor invited from the military hospital next door—presumably because the subject held the rank of general—I also do not know. I was not acquainted with Dr. Kogan, but the very fact of his participation in this examination speaks to his profound decency.

In his memoirs, P. Grigorenko assigns a leading role in this examination to E. B. Kogan. However, knowing Fyodor Fyodorovich's independent and even stubborn character when it came to defending his professional opinion—I witnessed such episodes during professor's consultations—I will allow myself to doubt this. Moreover, in a situation where the responsibility for the nature of the conclusion lies entirely with the chairman of the commission, and not with the ordinary and, even less so, invited members, it seems unlikely to me that Professor Detenhof could have been influenced by someone else's opinion and handed the initiative to others. It is more likely that Pyotr Grigorenko was later given a less than objective account of the commission's decision-making process, which, like all such procedures, took place behind closed doors. My assumption can be supported by the fact, mentioned by Yu. S. Savenko, that the authorities' subsequent pressure was directed specifically at Fyodor Fyodorovich, and not at the ordinary members of that famous commission.

Incidentally, anecdotes about Fyodor Fyodorovich's independent character circulated around the hospital. Doctors, it's no secret, love to gossip. And for psychiatrists, digging into others' personal lives is practically a professional trait. None of us could escape the fate of being a subject of colleagues' discussions. Especially such a vivid personality as Professor Detenhof. I could recount several dozen cheerful, harmless, and not-so-benevolent stories about him, which have become part of the more than century-long history of the Tashkent Psychiatric Hospital.

But I will limit myself to one episode where the professor revealed himself to be a person who recognized no authorities. A meeting was underway at the Ministry of Health of Uzbekistan, in which Professor Detenhof was participating. During the Minister of Health's speech, Fyodor Fyodorovich, sitting opposite him, suddenly pulls a plastic food container from his briefcase, opens it, and begins his meal. Anyone who has lived in Central Asia knows how much attention is paid there to so-called subordination, expressed, in particular, by the fact that subordinates are supposed to hang on their superior's every word. But here, the opposite was happening. The dumbfounded minister asked, “Fyodor Fyodorovich, what are you doing?” “Excuse me,” Detenhof replied imperturbably, “the meeting has dragged on too long, and according to my schedule, it is now lunchtime.”

I won't hide the fact that the information provided by Yu. S. Savenko was new to me, both the fact of the examination itself—such things were not publicized in the 60s and 70s—and Fyodor Fyodorovich's personal courage, a quality of his that was somewhat unexpected for me and of which I had previously been unaware.

But with all due respect to Yuri Sergeyevich Savenko, about whom I first heard in the early 90s before my departure to Australia, I am compelled to note a couple of inaccuracies which, though not of principal importance, are still... Firstly, during the period of the events described, Detenhof was not an 80-year-old elder, but almost ten years younger. Fyodor Fyodorovich did not live to be eighty, passing away in October 1973, just over a month after his 75th birthday.

Secondly, Yu. S. Savenko writes that the stress caused by the pressure exerted on him in Moscow hastened Fyodor Fyodorovich’s death. Yes, indeed, it was a time of trials for him. As my colleague and countryman I. Slobodskoy, who worked at the Tashkent Psychiatric Hospital at the time, wrote to me, F. F. Detenhof flew to Moscow for one day and returned from there in a distraught state.

But between these events and the professor's death, there was a rather long interval of 3–4 years, during which—as I was a direct witness—Fyodor Fyodorovich led an active teaching and scientific life. Psychiatrists know that the links between psychogenic factors and their psychosomatic consequences are very indirect, and mechanically linking stress and death is not always justified. This is especially true given that Fyodor Fyodorovich's death was immediately preceded by another, and perhaps more sensitive, blow for him: he, a specialist still perfectly capable of working and possessing a clear mind, was forced into retirement. In old age, stress in a familiar environment is endured much more easily than stress caused by a disruption of one's familiar routine.

It is unlikely that this administrative decision to dismiss the professor was prompted by the 1969 commission's conclusion. It was simply that in 1973, a man from the Rashidov clan came to power at the Tashkent Medical Institute (if my memory serves me correctly, his name was Uktam Aripov), who began his rectoral activities with a personnel purge. This “reformer” on an institutional scale sent into retirement (soon followed by their final rest) the professoriate that had once come from the center to develop medicine in the republic, and replaced them with the local national cadres who had by then ripened. As a student at TashMI in the 60s, I managed to witness the atmosphere, which later vanished, of not only high intellect but, perhaps more importantly, of intelligence, created by Professors Kampantsev, Volynsky, Terekhov, Gordon, A. Akovbyan, Rumi, Pavlova, Kogan, and others. F. F. Detenhof belonged to this cohort, with which he shared the sad fate of disgrace, known as a “well-deserved rest.”

In conclusion, I would like to thank my colleagues Sh. Magzumova, Yu. S. Savenko, and I. A. Slobodskoy, thanks to whom I had the opportunity to take this excursion into the distant past.

About the author. Refat Shakir-Aliev was born in 1945 in the Astrakhan region and spent his childhood and youth near Tashkent. After graduating from the Tashkent Medical Institute, he worked for many years as a psychiatrist, was the chief specialist for the Ministry of Health of Uzbekistan, deputy chairman of the Republican Society of Neuropathologists and Psychiatrists, and headed a department at the medical institute. He is the author of several dozen articles, brochures, and a monograph on clinical psychiatry. He moved to Australia in 1996. At first, he did heavy physical labor, and later worked as a doctor until his retirement. In Australia, Refat Shakir-Aliev took up literature. His stories and essays have been published in Australia, Russia, the USA, Germany, and Ukraine. He has won several literary contests. He lives in the city of Perth (Western Australia). (Source)

Prof. Sh. Sh. Magzumova,

(Department of Psychiatry and Narcology of the Tashkent Medical Academy)

Fyodor Fyodorovich Detenhof

The founding on January 1, 1920, of the Department of Psychiatry at the medical faculty of the Central Asian State University was, in essence, the beginning of the history of psychiatric science not only in Uzbekistan, but in all of Central Asia. The heads of the department, Professor Yu. V. Kannabikh, Associate Professor S. A. Preobrazhensky, Associate Professor L. V. Antsiferov, and later Professor F. F. Detenhof, trained a pleiad of highly qualified scientific and pedagogical personnel, practicing psychiatrists, and organizers of the psychiatric service. In this large and multifaceted activity, a significant place belongs to Professor F. F. Detenhof.

After graduating from the medical faculty of the 1st Moscow State University in 1920, F. F. Detenhof completed a clinical residency at the Korsakov Psychiatric Clinic, and an externship at the neurology clinic under the supervision of G. I. Rossolimo, while also working as a district narcologist. From 1925 to 1927, he worked as a resident physician at a sanatorium for patients with nervous disorders, later at the children's psychoneurological clinic in Moscow, the 1st city psychiatric hospital (now V. A. Gilyarovsky Psychiatric Hospital No. 3), as a research associate at the Gannushkin Research Institute, and as an assistant at the pediatric faculty department of the 2nd Moscow Medical Institute. In 1938, Fyodor Fyodorovich defended his doctoral dissertation on the clinical picture and course of mental disorders in chronic epidemic encephalitis. In 1940, he voluntarily came to Uzbekistan, to the Tashkent Medical Institute, where, having been elected head of the department, he led it for 30 years. As one of the founders of psychiatry in Uzbekistan, Professor F. F. Detenhof from the very first days took an active position in training scientific, pedagogical, and practical cadres of psychiatrists, developing both theoretical and practical aspects of psychiatry.

Professor F. F. Detenhof was a versatile researcher with a wide range of scientific interests. He made a great contribution to the development of such important problems in psychiatry as mental disorders in epidemic encephalitis, the peculiarities of post-influenza psychoses, and other infectious and postpartum psychoses that present with a schizoform picture. Professor F. F. Detenhof devoted much attention to the study of the somatic basis of psychoses and the treatment of the mentally ill, as well as to issues of regional pathology—mental disorders in malaria, local forms of encephalitis, intoxications, and brucellosis. During the Great Patriotic War, the attention of the department's staff was turned to mental disorders of wartime—of a traumatic and situational nature. Methods for treating traumatic epilepsy and traumatic mutism were developed and introduced into practice.

Professor F. F. Detenhof is the author of more than 100 scientific works, including 3 monographs. His monographs “A Guide to the Treatment of the Mentally Ill,” “The Treatment of Neuroses and Psychoses,” and “Psychoses and Mental Changes in Epidemic Encephalitis” received wide recognition and high praise from the scientific medical community. He wrote the first “Textbook of Psychiatry” for students in the republic. His research and works, distinguished by their depth of theoretical analysis, methodological precision, and special clinical mastery, always had a practical focus, serving the interests of the patient.

Fyodor Fyodorovich combined his multifaceted scientific and practical activities with extensive public work. For many years he was the chief psychiatrist of the republic, chairman of the Uzbek Society of Neuropathologists and Psychiatrists, and was a member of the editorial board of the S. S. Korsakov Journal and the Medical Journal of Uzbekistan.

The merits of Professor F. F. Detenhof were highly appreciated by the government—he was awarded three Orders of the Red Banner of Labor and many medals.

Professor F. F. Detenhof trained a large number of scientific workers; under his guidance, more than 10 master's and doctoral dissertations were completed.

F. F. Detenhof was a talented and erudite educator; his bright, informative, and emotional lectures and clinical analyses attracted a wide circle of students and specialists. Professor F. F. Detenhof was a broadly educated person: he knew world classical literature, music, and the fine arts—painting, and he himself loved to play music and to paint, especially landscapes of Central Asian nature.

Fyodor Fyodorovich is remembered as a person who was demanding of himself and his staff, a principled and highly intelligent leader, and a modest and kind man. His erudition, passion for scientific and practical activity, the generosity with which he shared his knowledge and experience, his simplicity and warmth in communication, his constant readiness to help, and his subtle sense of humor earned him the deep respect and well-deserved authority of the department staff, the institute, and the entire medical community of Uzbekistan.

From the Editor. Professor Fyodor Fyodorovich Detenhof is the man who saved the honor of Soviet psychiatry during the years of the large-scale use of psychiatry for political purposes. In the most high-profile and most documented case of General Pyotr Grigorenko, which lasted 17 years (1964–1974–1991), he and his entire forensic psychiatric expert commission (E. B. Kogan, A. M. Slavgorodskaya, I. L. Smirnova) in 1969 decisively rejected the 1964 inpatient forensic psychiatric examination report, headed by A. V. Snezhnevsky and D. R. Lunts (“paranoid (delusional) personality development with concurrent phenomena of initial cerebral atherosclerosis. Not culpable by reason of insanity. To a special psychiatric hospital for compulsory treatment”), and wrote: “Shows no signs of mental illness at present, nor did he show them during the period of the crimes with which he is charged. Culpable by reason of sanity. Does not require inpatient evaluation.” But 3 months later, the general was sent for another inpatient forensic psychiatric examination, which (G. V. Morozov, V. M. Morozov, D. R. Lunts, Z. G. Turova, M. M. Maltseva) duplicated the conclusion of the Snezhnevsky examination. And on the eve of this, F. F. Detenhof was summoned to Moscow, where G. V. Morozov and D. R. Lunts exerted criminally crude pressure on the 80-year-old man, demanding that he retract his conclusion, thereby hastening his death.