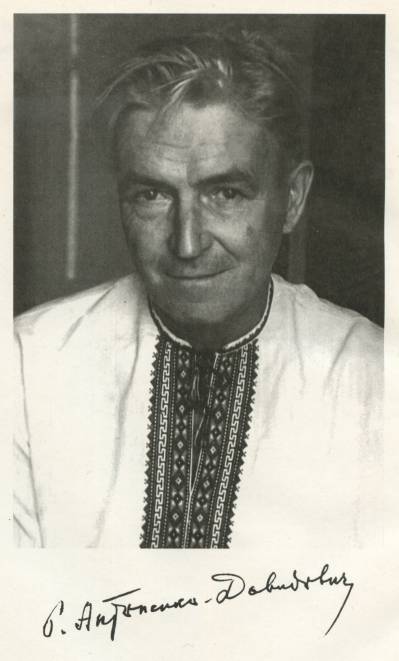

Yaroslav Homza. A Memoir of Borys Antonenko-Davydovych.

(From the book: Yaroslav Homza. Articles, Memoirs, Poems. Haidamaka Publishing House, Ocheretiane, 2002.)

IT WAS IN IRPIN

It was August 9, 1979, on his eightieth birthday. On this day, I visited Borys Antonenko-Davydovych in his Kyiv apartment. The welcoming host, as always, sat me at the table where “Symonenko used to like to sit,” and above which hung photographs of P. Kulish, M. Khvylovyi, M. Rylsky, and other figures of Ukrainian culture. About fifteen minutes later, the doorbell rang: new guests had arrived, the poet Volodymyr Sirenko and the engineer Borys Dovhaliuk, both from Dniprodzerzhynsk, whom I had not met before. After congratulating Borys Dmytrovych on his anniversary and chatting for about ten minutes, Sirenko suggested we drive to Irpin, where his acquaintance, the poetess Hanna Svitlychna from Pavlohrad, was vacationing at the House of Creativity.

On the way, Borys Dmytrovych told stories about various incidents from the life of V. Sosiura and about his good relationship with him. The pinnacle of their friendship was perhaps when, in the early 1960s, Sosiura brought him a poem with the dedication, “To the Cossack of the 2nd Zaporizhzhian from the Cossack of the 3rd Haidamak Regiment…” A few days later, during another KGB search, this poem was confiscated from Borys Dmytrovych, and its subsequent fate is unknown, as is even its title. Perhaps it was “Shot Immortality”?

Sirenko made arrangements with the director of the retreat, and we found ourselves with Svitlychna. I was struck by the poetess’s appearance. On the bed lay what at first glance seemed to be a normal woman, but when she extended her hand to Sirenko in greeting, I saw her arms were exceptionally thin, like little sticks.

Besides us, the children’s writer Larysa Pysmenna and L. Karpenko—a young woman from Dnipropetrovsk who was caring for Svitlychna—were there. Then the poet Ivan Hnatiuk from Boryslav arrived. And so, sitting at a table with a bottle of wine, we spent several hours in friendly conversation. The center of attention, besides our hostess, was, of course, Borys Dmytrovych. He recounted an episode from the first Decade of Ukrainian Literature in Moscow, in which he had directly participated.

The Ukrainian writers were to be received by Joseph Stalin himself, who had recently become the General Secretary of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). It must be said that after his work “Marxism and the National Question,” Ukrainian writers held a special respect for Stalin and hoped that he, as a representative of a national minority, would not allow the rampage of Great-Russian chauvinism.

At first, the “guardian” of the Ukrainian writers, Lazar Kaganovich, spoke with those present, shamelessly butchering the Ukrainian language.

Then came the time for the meeting with the little god. Stalin entered, looking around suspiciously.

He was asked:

“Joseph Vissarionovich, what is the difference between a nation and a nationality?”

“A nation is when a people lives in one territory, has one common history, a common language. A nationality is when a people lives in one territory, has one common history, but does not have a common language. Like you Ukrainians—one doesn’t understand the other.”

Everyone exchanged bewildered glances. Someone, I think it was Pylypenko, said:

“But the Ukrainian literary language was created by writers from both Eastern and Western Ukraine, such as Shashkevych, Fedkovych, and Franko.”

“And have these Shashko, Fedko, and Franko been translated into the Ukrainian language?”

Everyone felt uneasy—it was awkward to laugh and uncomfortable to remain silent.

After a short pause, Stalin repeated:

“I am asking: have these Shashko, Fedko, and Franko been translated into the Ukrainian language?”

Again, a tense silence. This began to irritate Stalin, and in a raised voice, he asked once more:

“I am asking: have these Shashko, Fedko, and Franko been translated into the Ukrainian language? Or do you not understand my question?”

Kulyk broke the tension:

“Yes, yes, Joseph Vissarionovich, they have been translated, translated.”

“So what’s the problem? Why bring this question up here?”

Thus, the little god fell from his pedestal…

Then Svitlychna asked Sirenko to read one of his poems. He read a verse:

У видавництво дід Гомер

Свої поезії припер,

Редактор так сказав Гомеру:

– Не піде, бо нема паперу.

Скипів, розсердився Гомер

І вірші за кордон відпер...

Там хтось знайшов рулон паперу

І видав книжечку Гомеру.

............................................

Щоб був папер, старий Гомер

В тайзі рубає ліс тепер.

The poem was quite topical and everyone liked it.

In the further conversation, Borys Dmytrovych reproached L. Pysmenna that not a single Ukrainian writer had even wished him a happy birthday, even though he was a member of the Writers’ Union.

“It’s just that nobody knows, Borys Dmytrovych,” she replied.

Soon we returned to Kyiv. I stayed with Borys Dmytrovych for another half hour, but the conversation somehow didn’t flow.

I spent that night at the home of Varvara Hubenko-Masliuchenko, the wife of Ostap Vyshnia. She treated Borys Dmytrovych with deep respect, but a friendly relationship never developed between them because Borys Dmytrovych was quite critical of her husband’s work, especially for his use of surzhyk, which is so shameful for us.

Over tea, the conversation touched on a little of everything, mainly on literary and cultural topics. And early in the morning, I left by bus for Romny.

The meeting in Irpin did not go unnoticed by the “sleepless” eye of the KGB. They summoned Larysa Pysmenna, who was terribly frightened and made all sorts of things up. And Hanna Svitlychna wrote that Borys Antonenko-Davydovych was an old man who had lost his mind, and that I, supposedly, had been drinking heavily! But Sirenko’s poem began to circulate around Kyiv and became quite popular.

Here, by the way, I want to mention another Svitlychna—Leonida, or Liolia, as she was affectionately called, whom I met a few years before the aforementioned meeting at Borys Dmytrovych’s apartment, right before her departure to Siberia to join her husband, Ivan Svitlychnyi, whom I knew only by correspondence. Eternal glory to you, my friends!

(Published in the newspaper “Skhidnyi Chasopys,” Donetsk, 1992, No. 12, and in the collection “Zona,” Kyiv, 1993, No. 4, pp. 154-156)

A MEMOIR OF A DEAR PERSON

I first heard of Borys Antonenko-Davydovych around 1942, thanks to his collection “Zemleiu ukrainskoiu” (Across the Ukrainian Land). After reading it, I even attempted to write a poem that spoke of how

“...Antonenko-Davydovych

Led us across the Ukrainian land.”

I got to know Borys Dmytrovych better after the publication of his article “The Letter They Long For” (about the letter Ґ) in “Literaturna Ukraina” (in 1968). I wrote the author a letter supporting his position. Our correspondence became quite active after the release of his book “Zdaleka y zblyz’ka” (From Afar and Up Close).

I want to tell you about my unforgettable meetings with this wise and modest man. Starting in the mid-1970s, I visited Borys Dmytrovych in his Kyiv apartment several times when returning from the Carpathians during my summer vacation. Once there, I met Leonida (Liolia) Svitlychna, with whose husband, Ivan, I had corresponded a little before. Another time, a former editor (in essence, a censor) of Borys Dmytrovych’s works came to see him. She exclaimed in surprise, in Russian:

“You always have new people here! Are they all nationalists?”

The evenings usually passed in friendly, interesting conversation about the state of the Ukrainian people, their culture, language, and history. We discussed the same issues in our active correspondence, which continued almost until his departure into eternal life. A part of the correspondence that accidentally survived a KGB search was published in the journal “Zona,” issue 11, 1996. [This publication is not included here. We are skipping the repetition. – V.O.].

Borys Dmytrovych recalled how he was sentenced to be shot. (He was repressed in 1935 and rehabilitated in 1956). He was saved by a coincidence. The case investigator was from Kuban, and the arrested writer knew the history of the region well. This intrigued the investigator, who, during the interrogation, asked Antonenko-Davydovych to tell him about his native Kuban. The investigation was already over, but the accused had not yet finished his story about Kuban. Then the investigator said: “We’ll have time to shoot you later, and since we’re having a conversation, the execution can be postponed.” Later, a telegram arrived ordering the cancellation of all executions.

Borys Dmytrovych was a very interesting storyteller. Before we knew it, we were at Svitlychna’s… [Skipping a repetition. – V.O.].

The last time I visited Borys Dmytrovych was in the summer of 1983, almost a year before the end of his earthly journey. Approaching the entrance of his building, I saw two “working men” standing nearby with “tormozoks” [lunch bags] in their hands. At that time, the ailing Antonenko-Davydovych was being cared for by Mrs. Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska. When I arrived, she was just about to go out into the city for a short while and so gladly asked me to take Borys Dmytrovych for a short walk down the street. We all went out together. The two “working men” with the “tormozoks” were still lingering near the entrance. When we turned from the street onto the alley, I looked back and saw them on the street. They were following us. They had a “job”—to watch the “enemy of the people.” They feared him even when he was frail and old.

I pointed this out to Borys Dmytrovych. He said simply: “You know how many of them walk around here? And every day. I’m used to it.” Borys Dmytrovych died on a sunny spring day, May 9, 1984. When I learned of this, I didn’t leave my house all day; I was overwhelmed with grief because I had lost a dear person.

(Published in “Ukrainska Hazeta,” Kyiv, 1999, No. 14)