Source: “Tyzhden” Magazine, August 4, 2010, No. 32 (145)

Valeriy Shevchuk on Yevhen Kontsevych

“Tyzhden” Magazine, August 4, 2010, No. 32 (145), http://www.ut.net.ua/art/168/0/4207/

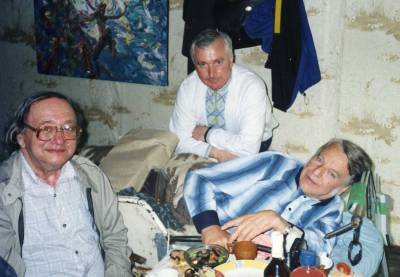

On July 21 (2010), Yevhen Kontsevych, a legend and symbol of the Sixtiers generation, passed into eternity.

He was one of the most amazing and brilliant personalities I had the good fortune to meet and with whom I maintained a long friendship. I met him in 1952 through the outstanding translator Borys Ten, also a Zhytomyr native, whom I had just met at the time; he informed me that there was an extraordinary young man in our city who, like me, was a novice writer but was forever confined to his bed—Borys Ten himself looked after him. And so, his son Vasylko led my brother and me to 2nd Shevchenkivskyi Lane, No. 12, where I saw a young man with a noble face, sitting in a wheelchair, who had absolutely nothing specifically invalid-like about him; moreover, he seemed to radiate, or exude, light from within himself. And it was with this light that he greeted us. This was his main characteristic as a person, for he belonged to the exclusively light-bearing personalities and constantly streamed with that light, which attracted many people to him who, perhaps, needed his light. And another peculiarity: he was always surrounded by domestic animals and birds, and most of all in that homestead were pigeons, which filled the yard, fluttering to their perches near the dovecote or flying back to the ground. He could not imagine his life without such an entourage. He often said that his childhood dream was to become a veterinarian, and that he became a writer by accident.

So, were it not for his confinement to one place, he would never have thought of taking up writing fiction. I did not argue with him on this point, except to tell him that in our literature there was one great poet who was also a veterinarian—Oleksandr Oles, who was still banned at the time. I myself believe that when a talent is awakened in a person, it is not the person who decides whether to develop it or not, but the talent itself, according to its power. But in general, he is not called “the writer from Borys Ten’s nest” for nothing—it is beyond doubt that the impetus for creativity was given to him by this, as I call him, great man of Zhytomyr. The fact is that Borys Ten was a priest in his youth, and then an educator—and he was a teacher by the grace of God. He surrounded himself with literary youth, and in his garden, one could always find some young man with a notebook of poems, and the old teacher, sitting opposite, would teach him the secrets of poetic creativity.

My brother and I somehow immediately became literary brothers-in-arms for Yevhen, and our friendship was founded on this, although people of different ages, genders, occupations, and levels of development came to him. And he could talk to everyone, and since he had an extraordinary mind, people listened to him with unflagging attention.

When we appeared at his place, he, at the urging of Borys Ten, was writing humorous sketches and had already published one of them in “Pershyi Snip,” an almanac that came into being thanks to the same tireless Borys Ten. I called the style of that writing “kovinkovy” (from the surname of the humorist Kovinka, which was based on clownish buffoonery), and being a boy who was a bit overly serious, the first thing I did, seeing that I was not dealing with a graphomaniac but a truly talented person, was to dissuade him from his desire for “buffoonery” and convince him that he absolutely needed to become a serious, that is, a real, writer. And my brother and I also lambasted him for the remnants of socialist realist poetics and eventually found a consensus. Today’s critics and literary historians call this moment the birth of the Zhytomyr School of Prose.

The Roar of Deafness

Yevhen Kontsevych became disabled due to an accident. He lived on the opposite side of Zhytomyr from my neighborhood. There was no river there, but one flowed next to my parents’ house. So Kontsevych came here to swim, but he didn’t take into account that the river was full of underwater rocks. With youthful bravado, he jumped into the water from a cliff and severely injured his spine, remaining confined to a bed forever. In general, he was a handsome man, nearly two meters tall—a rare sight at that time, as there were not many such tall people. The tragedy occurred when he was in the ninth grade at secondary school No. 23. I am generally inclined to fatalism, so I interpreted this case in my own way: he studied at school No. 23, and my brother and I at school No. 32—the same numbers, just rearranged; he was injured in the area where my brother and I lived; finally, when we met, I was working at a concrete plant not far from his house; so, fate seemed to be binding us together.

How did he manage to hold on? It cannot be told briefly—it was not a simple matter. But Yevhen was an amazing person who attracted people to himself, and those people, visiting him (and I too), never felt that he was a cripple; he looked more like a patrician who had reclined on a couch for conversation (as the Romans, at least, conducted their discussions). Not only did he never speak of his ailments and physical and psychological problems, but on the contrary, he seemed to spiritually heal others, the healthy ones, and he did this in an exclusively unobtrusive manner. So I repeat the definition I’ve already given—he was a true light-bearer.

Yevhen had all sorts of times: better and worse, but the worst came when the KGB took an interest in him. I have told the story of this relationship, which defined his life, in detail in a large chapter of my book “On the Shore of Time. My Zhytomyr. The World Before My Eyes. After School,” Lviv, 2009, which is titled “The Writer from Borys Ten’s Nest” on pages 363-444; those who are interested can read it. Here I will only say that those inhuman people subjected him to psychological torture. It was not so much about collaborating with that diabolical organization as it was about denouncing the people who gave him samvydav to read. And that was the most difficult period of his life: they wanted to expel Kontsevych from the Writers’ Union, deprive him of his meager disability pension, etc. It is clear that this had a negative impact on his creative work—he did not write anything for a long time. In general, doctors considered him doomed and could not understand why and how he was living. In such cases, he would joke that he was immortal, and against all logic, he lived to be 75. Soviet functionaries wanted to make him a kind of Pavka Korchagin, of course, on the condition that he would serve the communist regime as Mykola Ostrovsky had. However, he did not want to serve the evil empire. He wrote little, but what he wrote came from his own heart, not someone else’s. His little books under the title “Dvi Krynytsi” (“Two Wells”), which collected his novellas, were published several times, but he also wrote articles, speeches, and publicist works. He also corresponded with many people, particularly the Sixtiers, to whom he belonged (I presented my correspondence with him in the aforementioned “On the Shore of Time” on pages 420-443)—these letters still need to be collected, but in general, the people of Zhytomyr managed to collect his writings into a handsome volume of 640 pages and publish it for the writer’s 75th anniversary. It is called “Klekit Hlukhoty” (“The Roar of Deafness”) (PP Ruta, Zhytomyr, 2010). Why is it named so? Because towards the end of his life, after a stroke, he completely lost his hearing.

“Do you think deafness is silence?” he once said to me. “No, it’s a roar.”

Was Yevhen Kontsevych a well-known person? Of course, the official tabloid or some other conformist press did not promote his name; besides, I am sure that he did not need it. But he was well known in literary and artistic circles, and one can learn about the people who were drawn to him from his famous embroidered towel, on which those who visited him signed their names—there are about 500 of them, and this list is printed in the book “The Roar of Deafness.” In Zhytomyr, an idea even arose to make a monument to this towel; there were projects from sculptors. Yevhen himself told me that Viktor Yushchenko wanted to buy this towel from him, but Kontsevych did not want to sell it. So, to say that he is a little-known writer is impossible; he is known, and very well, but in a certain circle, in particular, most of the Sixtiers considered it an honor to visit him.

Ukrainian Neorealism

Yevhen Kontsevych’s writing style is simple: it can be called modernism in the form of neorealism. In our triad, which current critics call the founders of the Zhytomyr School of Prose, we did not try to erase each other’s individual faces, as the socialist realists did, but on the contrary, each went his own way, that is, remained a separate creative individuality, while adhering perhaps only to a common aesthetic method—in our case, this was neorealism, the roots of which were in post-war Italian cinema; it turned out that this method could be easily transplanted into Ukrainian soil—here it became indigenous. Of course, we did not speak of any “school,” and did not even have it in mind—this “school” was invented in the late 1980s, and we never objected to such a term, as the creative connection between us was indeed constant. So if that school formed on its own and is recognized in the literary world, then why shouldn’t it exist? Yevhen Kontsevych thought so too.

Ivan Dziuba was absolutely right when he said that Yevhen Kontsevych was a “legend and symbol of the Sixtiers generation.” Vyacheslav Chornovil called Yevhen a man of great attractive force. And Vasyl Stus also noted his light-bearing quality: “he frightened me with his nowhere-and-no-way-rooted optimism: a pure spirituality, freed from the flesh—the pure spirit of the eyes.” How wonderfully and accurately said: “The pure spirit of the eyes.”

That Yevhen Kontsevych belonged to a special group of people among the Sixtiers, no one doubted. After all, they were so different, those who are called by that name. There were among them the strong and the weak in spirit; the pure in thought and the compliant; those who burned their fire, and those who hid it; those who did not hesitate to sacrifice themselves for the resurrection of their native land and people, and those who hid in conformism. There were heroes and renegades among them, but in general, this was a daring generation, with missionary impulses, who, for the most part, did not seek benefits for themselves, although among them one can find those who strove for such. I call them the “youths from the fiery furnace” (I also have a novel with that title). They acted and were consumed in the evil empire in different ways, they departed from this world in different ways, perished in concentration camps, or returned from there with broken health, and sometimes spirit. They were not gathered into one organization or sect, but they grew and acted, and their goal was, despite everything, light-bearing, and they burned a fire that does not consume, but illuminates human souls.

Yevhen Kontsevych was perhaps the most special among them. Frail in body, like no other, but powerful in spirit; confined to one place, but with the ability to rise spiritually, like his beloved pigeons, into the sky. He was a teacher, but had no official diploma for it. His only weapon was the clarity of his soul and incredible endurance in the face of physical helplessness; thus, the example of his life can be recognized as unique.

A New Chain

“Why are there none like that now?” people sometimes ask today. But I am sure that they exist. They have already come and are coming. They are not on the show-maidans, not on television screens, not on the pages of the tabloid and colonial press that now dominate. But they are coming. And that is because they must come, if we want to believe that this world is life-giving and will not drown in its own garbage, which some see as real value. So I believe that they will come, if only more people say: “We are them. We are not of the world of mammon and banditry that has seized power; not of the world of the strong, but greedy; we are not of the world of the strong but impure in soul. And the only thing we need is not to bite each other like a pack of dogs, but to take each other by the hands and create a new chain.”

And when that happens, they will come, for they are already on their way. And may everyone with a pure spirit feel this in the depths of their soul. It doesn’t matter what we call those who are coming: dissidents or true patriots, what is important is that they and all of us learn to unite. Because the evil that has come to our land and once again wants to destroy our people as a world entity is not universal and immortal. It is cruel, harmful, shamelessly aggressive, deceitful, but it is temporary. And the more people there are who will not go with them, the sooner their inglorious end will come. The heroes of our past bear witness to this. They knock on our chests, like the “ashes of Claes,” and call on us not to be indifferent and not to fall asleep. I know: among those awakeners, Yevhen Kontsevych remains in his place, though he has already walked the paths of eternity—one of the light-bearers of the Sixtiers generation.