Many political prisoners and dissidents had dealings with an investigator named Mykola Ivanovych Kolchyk. It is not known whether he is still alive in Ukraine or beyond its borders, but his name is inscribed in the history of Ukraine in black letters.

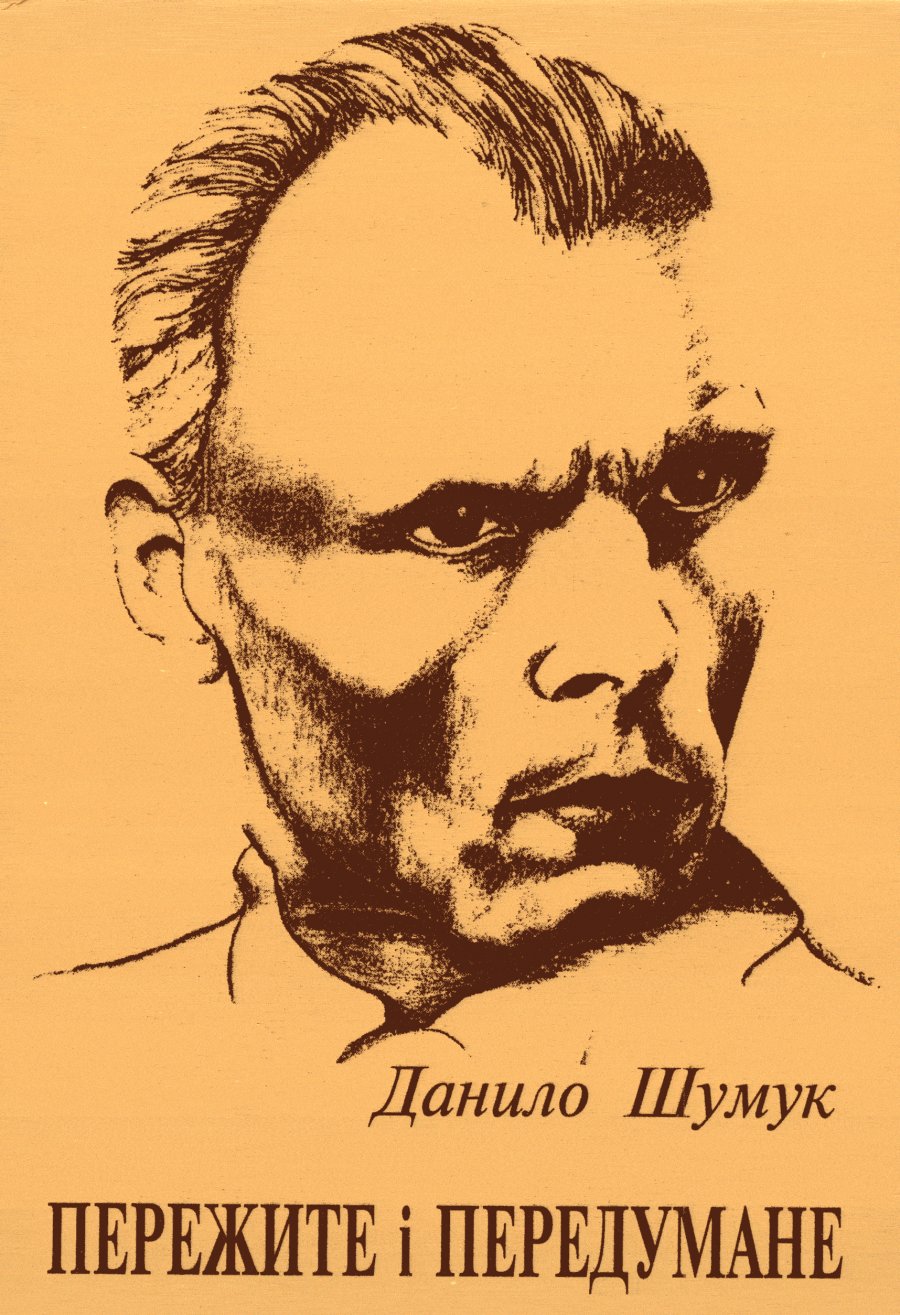

The earliest mention of Kolchyk known to me is in the book “Beyond the Eastern Horizon” by Danylo Shumuk. It concerns Shumuk’s arrest in 1957. By that time, as a member of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine, he had served 4.5 years in the Polish prison Bereza Kartuska, several months in a German concentration camp near Lokhvytsia, from which he escaped, and 10 years in Soviet concentration camps. The Soviets arrested him in December 1944 for his involvement in the insurgent movement, gave him a death sentence, which was commuted a few months later to 20 years of hard labor. He was released in 1956. He was not allowed to live in his native Volyn, so he had to settle in the Dnipropetrovsk region. On November 19, 1957, he was summoned to the KGB and offered to cooperate with the “organs.” He refused. The next day he was arrested. Initially, the case was handled in Dnipropetrovsk by Captain Moroz. Then it was transferred to Kyiv, and subsequently to Lutsk. There was no real case to speak of: just a few intercepted letters. But they gave him 10 years. And that’s not all. For the aforementioned memoir and for his communication with the *shestydesiatnyky* (Sixtiers), Shumuk received another 10 years of special (cell-based) regime in 1972, 5 years of exile, and was declared an especially dangerous recidivist. His total “service” was 42 years, 6 months, and 7 days. Amnesty International recognized him as the world’s longest-serving political prisoner.

Danylo Shumuk died in Krasnoarmiisk, Donetsk region, on May 21, 2004, in his 90th year.

Shumuk wrote about one of the interrogations in Lutsk in early 1958:

“I was called to the office. A captain sat in the room opposite the door, and a lieutenant sat at another desk to the left. The captain was about 35 years old, and the junior lieutenant was about 33. Both were well-built and not stupid. After examining me with the probing eyes of a Chekist, the captain said:

‘I will be your investigator, my name is Matviienko, and this is Junior Lieutenant Kolchyk, he will be our secretary.’”

Shumuk does not mention Kolchyk again, but it is clear that he participated in fabricating his case.

Second on our list are Valentyn Moroz and his wife Raisa, a Greek from the Azov Sea region, of the Levterov family.

This same Kolchyk interrogated V. Moroz’s co-defendant, the teacher Dmytro Ivashchenko, in 1965–66 and persuaded him to plead guilty. The former front-line soldier, with Kolchyk’s light touch, received a 2-year prison sentence for “propagandizing anti-Soviet literature”—he had read books by Ivan Koshelivets and Bohdan Kravtsiv, and also had samvydav poems by Symonenko, Vinhranovsky, Pavlychko, and Lina Kostenko.

When Valentyn Moroz’s famous “Report from the Beria Reserve” appeared in samvydav, the author was transported from Mordovia to Kyiv in the autumn of 1967 with the intention of opening a new case. He was held at 33 Volodymyrska Street for a year and a half. Investigator Kolchyk brought Moroz to a very grave physical state. But he allowed Raisa to see her husband several times. Across a table, of course, in the presence of guards.

“My relationship with Kolchyk is an entire epic in itself,” says Ms. Raisa. “‘Oh, a Greek woman! I’m also Greek on my grandmother’s side.’ And he treated me with a chummy familiarity, as if we were compatriots... It all started back in Lutsk.”

“Kolchyk granted me a visit on April 1, 1969, in Kyiv, on my birthday. He was playing the friend! This was almost the end of the investigation. He said they were closing the case for lack of evidence, there were no testimonies…”

“But at the same time, he drove me to the point of fainting. He knew how to do it: he’d play the part of a friend, joke around, mention his Greek grandmother, and then suddenly, out of the blue: ‘And now for a question, Raisa Vasylivna. Have you read the “Report”?’ I say: ‘No, I haven’t.’ To which he replies: ‘Aha, you haven’t?’ And he starts rummaging, as I can see, through my letters. I frantically think: ‘What could I have written there that he’s about to catch me red-handed…’ ‘I was at Slavko Chornovil’s a few days ago,’ he quotes from my letter, ‘he fed me some very tasty dishes.’ ‘And what kind of dishes were those?’ So, he had found and snatched the very phrase that related to the ‘Report.’ I say: ‘That was so long ago, I don’t remember what the dishes were.’ Then he starts joking again, saying something completely off-topic, and suddenly: ‘And now I have to tell you something very unpleasant…’ Again, something happens to my heart, it plummets. And he says: ‘We have to conduct a search of your place.’ I was immediately relieved because I had nothing in the house at the time. And he, obviously, sees this, as he was a good psychologist. He acted as if he wasn't looking for anything. But after that conversation and that search, my neighbor had to call an ambulance for me three times.”

Nine months after his release, on June 1, 1970, Valentyn Moroz was arrested for the second time and sentenced for “Report from the Beria Reserve” and the articles “Amidst the Snows,” “Chronicle of Resistance,” and “Moses and Dathan” to 6 years in prison, 3 years in special-regime camps, and 5 years of exile, being declared an especially dangerous recidivist. This was a grim warning to all dissidents. But in the 1970s, the 10+5 term became common.

As early as January 1974, during a visit, Valentyn told Raisa that on July 1, he would begin an indefinite hunger strike to demand a transfer from Vladimir Prison to a camp. She turned to Moscow human rights activists: what to do? The message came back: a press conference. It was terrifying: a defenseless woman from the provinces speaking out against the entire Evil Empire! But she dared. She only needed to know for certain if Valentyn was on a hunger strike. Raisa went to Vladimir. The main street there leads directly to the famous Central Prison. Along the way, she saw a movie poster: “No Way Back.” And the Lord guided her: upon meeting the prison warden, she immediately pounced on him: “My husband is on a hunger strike, he’s going to die, and you’re doing nothing!” And the warden confirmed: “Well, you see, we tell him the same thing: just stop the hunger strike!” That was all Raisa needed to hear. They convened a press conference for foreign journalists at a dissident’s apartment in Moscow. When she looked down from the 8th floor, the courtyard was full of black cars and KGB agents! But there was no turning back... With this heroic act, she saved Valentyn: an unprecedented campaign in defense of the Ukrainian political prisoner was launched worldwide.

But when Raisa was returning from Moscow to Ivano-Frankivsk, they gave her such a scare… You can read about it in her interview on the KHPG website. And Kolchyk gloated: “Well, we gave Raisa a good scare…”

After the interview, Raisa avoided conversations with Kolchyk. So he brought her terrified brother from the Donetsk region, who desperately shouted: “What are you doing? They’ll arrest you!”

The KGB agents say: “Raisa Vasylivna, you blame everything on us. If something happens to you, will you blame us then too?” I say: “Well, if something happens to me, I probably won’t be in a position to blame anyone.” I’m thinking: will they kill me, or what? And he says: “No, just a little something will happen to you.”

The next day, a stone hits her just below the eye.

Then they break the windows of her apartment and her neighbors’ and start a rumor: it’s because of their male visitors.

“I had no doubt it was the KGB, but on the other hand, I didn't catch them red-handed. I turned to the Muscovites. They said: it was them.”

“They summon me: ‘You know we’ll arrest you.’ My only argument was this: ‘So what, am I supposed to save my own skin when my husband is on a hunger strike? He’ll die! What am I supposed to do? I’m doing what any person would do.’ This argument worked. I wasn’t arrested. But Raya Rudenko was later arrested for almost the same thing.”

“In 1971, I started writing petitions in defense of Valentyn. In fact, my first petition was written by Slavko Chornovil, and I signed it. Then I started writing them myself. And then there was that first interview in 1974, when he was on a hunger strike for 5 months. It was very hard on me. The persecution began, immense pressure on me. It wasn’t just that they summoned me for interrogations. The worst was when they asked me: ‘And how old is your son?’ This was when my son was about 13 or 14. I had a premonition then that he didn't ask that for no reason, that KGB major, I don't remember his name. I left and thought that they would probably start putting pressure on me through my son.”

“And so it happened. They turned him into a delinquent, put him on police records. They planted a bicycle on him. Supposedly, some boy had stolen a bicycle from the police chief and was selling it to my son, and then claimed my son had stolen it. And my son said he had bought it for three rubles. Their scenario failed, because he really did buy the bicycle for three rubles. But he was put on police records and kept there almost until the tenth grade.”

“In the ninth grade, my son calls me from school and says: ‘Mom, they want to put me in a psychiatric hospital.’ ‘Why?’ ‘Because I’ve been on police records for several years.’ ‘What?!’ I immediately call Moscow and tell all my friends: ‘They’re taking my son to a psychiatric hospital. They kept him on police records for nothing, and now they’re taking a child to a psych hospital.’ They released him immediately, no psychiatric hospital, as soon as they heard I was going to raise a fuss.”

“Or some friend would give him three rubles and say: ‘Go buy some vodka.’ But he was a minor, and minors couldn’t buy vodka then. It was a good thing he was already savvy, he said: ‘No, you go buy it yourself.’”

Meanwhile, our Kolchyk was performing other heroic feats.

During the investigation of cases against leading *shestydesiatnyky*, the KGB agents desperately needed “penitents,” preferably with famous names. They set their sights on Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky’s grand-niece, Mykhailyna Khomivna, and Ivan Franko’s granddaughter, Zinaida Tarasivna.

Here is what Ms. Mykhailyna recounted:

“One day, the KGB organized a face-to-face confrontation for me and Franko. It was perhaps my most difficult experience. They took me from work (my good fortune in my misfortune was that my boss, Neonila Kucheriavenko, was an exceptionally decent person; undoubtedly, these constant summonses were meant to be a signal for harassment at work, but thanks to her, these signals were not heard), brought me to the KGB, led me to a room I hadn’t been in before, and Zinovia Franko was already waiting for me there. She rushed toward me with open arms. I limited myself to some vague gesture. Investigator Mykola Kolchyk was present, the same one who had ‘worked on’ Dziuba, the most ‘intelligent’ of the KGB agents I had to meet (I knew him from our university days, he was my age, studied law, and our portraits on the board of honor always hung side by side). Kolchyk began: ‘On such and such a date, in your apartment, Zinovia Franko gave Andriy Kurymsky the “Ukrainian Herald,” etc.’ I replied: ‘You have asked me this dozens of times, and I have answered this question dozens of times, and I will answer it once more: I don't remember anything of the sort.’ To which Kolchyk said: ‘But Zinovia Tarasivna claims the opposite.’ Kolchyk spoke, while Franko remained silent, growing increasingly tense internally. For a moment, Kolchyk looked at her expectantly, and finally roared: ‘Well, Tarasivna!!!’ Franko started to say something quickly… The situation was horrifying and at the same time astonishing: they treated me, despite my thwarting all their plans, with complete respect, whereas her… This is how they broke people. When I walked out onto the street after that confrontation, my legs were buckling under me. I remember as if it were today that I immediately went to Dziuba’s at the ‘Dnipro’ publishing house, which was located not far from the KGB—I wanted to touch a human being…”

With a “penitential” statement squeezed out of her by Kolchyk, Zinovia Franko appeared on television in the spring of 1972, with her eyes cast down. She said, in particular, that she had tried to pass “one anti-Soviet document” abroad through Yaroslav Dobosh. Do you think it was a call to overthrow Soviet power? No, it was a microfilm of the “Dictionary of Rhymes in the Ukrainian Language.” The dictionary had already received recommendations for publication from several university departments. It was “anti-Soviet” only because it was compiled by the political prisoner Sviatoslav Karavansky. The dictionary was published in 2004 by the BaK publishing house in Lviv. Turn through all of its 1027 pages and try to find anything anti-Soviet there…

In 1972–73, Kolchyk successfully “worked on” Ivan Dziuba, which resulted in a penitential statement that brought great sorrow to Ukrainian society, especially to political prisoners. That statement was published on November 9, 1973, in the newspaper “Literaturna Ukraina.”

Historian Yuriy Shapoval writes that Kolchyk played the role of the “good investigator” in Dziuba’s case. But there was also a “bad one”—a senior investigator for especially important cases, Major Hryhoriy Petrovych Bidiovka, who was specially brought in from the Ternopil region. This Bidiovka, by the way, handled the case of Mykola Kots in 1967, Levko Horokhivsky in 1969, and Mykola Horbal in 1970. Horbal, already a People’s Deputy of Ukraine, once met Bidiovka and amicably suggested they write a book together. For the sake of national consolidation—why the Ukrainian Bidiovka saw an enemy in the Ukrainian Horbal. And who benefited from this. “I’m not a writer,” the KGB agent began to demur. “Don’t be disingenuous, Hryhoriy Petrovych, I have the search protocol you wrote—it’s brilliantly written. Write in that style, and I will write about what I endured in the basements of your KGB…” (See M. Horbal, “One of the Sixty.” Kyiv: ArtEk, 2001, pp. 129-132). Bidiovka did not take advantage of this good opportunity to confess. He went to hell without repentance.

THEY will not write. But THEY wrote volumes of black “case files,” from which no one will ever expunge them.

I will repeat what I said in my first article. Perhaps the descendants of the KGB agents mentioned and not mentioned here have grown up on good food to be respectable citizens, and it will be unpleasant for them if people nod their heads and point fingers at them. But they must know that the Judge of this world punishes the sins of the parents in the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren to the third and fourth generation. But He also shows mercy to the parents for the prayers and virtues of their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

The path to repentance is closed to no one.

In the photos: Danylo Shumuk, Raisa Moroz-Levterova, Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska.