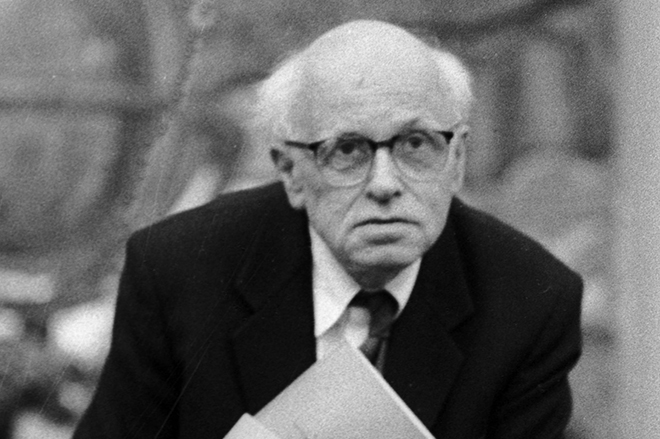

Thirty years ago, on December 14, 1989, Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov died. The historical distance that separates us from this date allows us to say without reservation: it was a different era. A different spirit of the time—the air was thick with the feeling of a historical turning point, of inevitable change. The wind of change had gripped not only the USSR, but the entire world.

Anxiety and Hope

Sakharov’s worldview can be described in two words from the title of one of his publicist articles: “anxiety and hope.” In 1986, the time came for his hopes to be realized. The USSR and the US were negotiating arms reductions, the Berlin Wall—a symbol of a divided world and the Iron Curtain—had fallen, and over three years, almost all political prisoners in the Soviet Union were released. The first to be released from his Gorky exile was Sakharov himself.

Freedom, creative energy, and the absence of impenetrable borders were for Sakharov a natural state, a reflection of the fundamental properties of the universe in human civilization. Disunity, violence, and oppression are, on the contrary, unnatural: they lead humanity, which possesses nuclear weapons, to ruin.

Twentieth-century science, which Sakharov the scientist embodied, united the physics of the infinite universe and the physics of elementary particles. Sakharov as a social thinker extrapolated this vision to world politics, linking international security (the survival of all humanity) with the protection of human rights, with the fate of each individual prisoner of conscience.

Sakharov's Nobel lecture begins with the words: “Peace, progress, human rights—these three goals are inextricably linked; one cannot be achieved by neglecting the others.” And it ends with a list of the names of 112 Soviet political prisoners.

The ability to combine a global vision with meticulous practical attention to detail is a remarkable quality of Sakharov's, rare among people and even rarer among politicians who make decisions that can determine the fate of the world and of peace. In those years, it seemed that the unity of the micro- and macro-political had taken root in the world.

Alone on the Battlefield

However, Sakharov’s life ended on a tragic note. In the last months, and especially in the last days of his life, Sakharov was not understood and not heard in his own country. “Tomorrow there will be a battle,” Sakharov told Elena Bonner just before his death. And in this political battle, he was practically alone.

The year 1989 was not only the last year of Sakharov's life, but also the first year of real (albeit limitedly free) political life in the USSR. And it is very important, when remembering the day of his death, to remember Sakharov the politician.

The canonical image of Sakharov, which began to form immediately after his death (“He was a true prophet. A prophet in the ancient, primordial sense of the word…”—D. S. Likhachev), places Sakharov above politics (he appealed to conscience and preached ideals), but thereby makes him seem as if he were not of this world, far from the “dirty” political struggle.

However, in the last six months of his life, it was Sakharov who showed what Russian politics should and could have been.

The motivation for Sakharov’s political participation was personal and public responsibility. Sakharov not only set a high moral bar but also sharply raised the status of political action. “The voters, the people, elected us and sent us to this Congress so that we would take responsibility for the fate of the country,” he addressed the deputies in the first hours of the First Congress of People's Deputies. For Gorbachev, the Congress was a tool for implementing reforms, a means to support his policies. Sakharov endowed the assembly of deputies with a higher order of political subjectivity.

Sakharov championed the basic principles of democratic culture, without which political action loses its legitimacy. At the opening of the Congress, Gorbachev, following his political logic, wanted to immediately consolidate his political positions and held a vote on the composition of the Congress presidium, with himself at its head. “There is always a procedure: first discussion, first the presentation of platforms by the candidates, and then the elections. We will disgrace ourselves before our entire people—this is my deep conviction—if we do otherwise,” Sakharov objected.

He tried to call the Congress to a fundamental political reform. Proposing a “Decree on Power”—to affirm the Congress’s right to appoint candidates for top state positions, to repeal Article 6 of the Constitution on the leading role of the CPSU, and to begin drafting a new constitution.

While the majority of “democratic” deputies, even when sharply criticizing the authorities, stayed within the framework set by Gorbachev (they limited themselves to exposing abuses, openly discussing pressing problems and reform plans), Sakharov put forward political demands that seized the political initiative and the political agenda from the authorities. At the same time, he sincerely offered Gorbachev not confrontation, but a union in implementing his political agenda.

It would seem, why cast pearls before an “aggressively obedient majority” that drowned out his speeches and subjected him to obstruction. But the Congress was broadcast live, and Sakharov appealed to society for support: “I appeal to the citizens of the USSR to support the Decree individually and collectively.” In the summer, striking miners included the repeal of Article 6 in their list of demands.

A Lost Chance

The second and, perhaps, main motivation for these actions was that Sakharov saw the impending crisis. Here, the fundamental scientist, the physicist in him spoke, registering that the resultant of social, economic, and political aspirations and processes was leading the state system to ruin.

He criticized Gorbachev for his inaction and appealed directly to society. On December 1, he published an appeal for a two-hour warning strike in support of his demands. Even among the members of the Inter-Regional Deputies' Group, only 5 people supported the appeal. However, strikes took place in many cities of the USSR. On December 14, at a meeting of the Group, he was sharply criticized for his call. That evening, Sakharov died of a heart attack.

The answer to the question of whether Sakharov could have changed the course of history is impossible to know. And yet, in 1991, more than half of the residents of the USSR stated that they shared Sakharov's social and political views.

Sakharov clearly demonstrated the signs of a great politician. He was able to see the political process holistically, combining a global goal with specific solutions, he recognized real threats that surpassed short-term political confrontation, he understood the fundamental importance of political institutions, and he was able to go beyond his usual support group (the scientific and technical intelligentsia) to seize the political initiative.

The fate of Sakharov, his historically premature death, is an answer to the longing for a “Russian Havel” that continues to this day. Sakharov not only could have become, but was, a Russian Havel. But one who was not heard and not recognized as such. First and foremost, not even by society, but by the elite. And not only its conservative part, but its “democratic” part as well.

A chance, including a historical one, comes only once. We will not have another “Havel.” New turning points in history will look different. The main thing is to see them and make the right choice.

P. S. Sakharov’s last speech, written but not delivered, was about legal reform: access of lawyers to their clients and the length of pre-trial detention. Familiar problems, aren’t they?

Sergei Lukashevsky is the director of the Sakharov Center.

The original article can be read here.