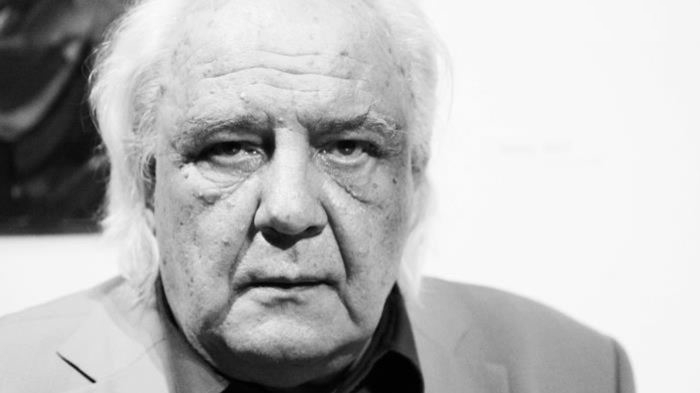

On October 27, 2019, Vladimir Bukovsky—human rights activist, publicist, political and public figure, a dissident of the Soviet era, and author of sensational exposés related to psychiatric repression against dissenters in the Soviet Union—died in Great Britain.

Vladimir Bukovsky was born on December 30, 1942, during the evacuation in the city of Belebey (Bashkir ASSR) to the family of a writer and journalist. He studied in Moscow, where the family returned after the evacuation. From the age of fourteen, he felt himself an opponent of communist ideology. In 1959, Bukovsky was expelled from school for participating in the publication of a handwritten journal and continued his studies in an evening school.

In 1960, along with Yury Galanskov, Eduard Kuznetsov, and others, he was one of the organizers of regular youth gatherings near the Mayakovsky monument in the center of Moscow (“Mayakovka”). In the spring of 1961, the KGB conducted a “prophylactic chat” with Bukovsky, and in the autumn of the same year, the homes of the “Mayakovka” activists were searched. During one of these searches, a text by Bukovsky was seized, which contained reflections on the need to democratize the Komsomol (later classified by the investigator as “theses on the collapse of the Komsomol”).

In 1961, Bukovsky was expelled from Moscow State University, where he had been studying at the Faculty of Biology and Soil Science.

In the first half of the 1960s, seeking his own way to resist the Soviet regime, Bukovsky considered various methods of struggle, including conspiratorial ones, but ultimately preferred open forms of resistance.

In May 1963, Bukovsky produced several photocopies of Milovan Đilas’s book “The New Class.” These copies were seized during a home search, and Bukovsky himself was arrested and sent to the Leningrad Special Psychiatric Hospital with a diagnosis of “paranoid personality disorder.” In the hospital, Bukovsky met Petro Hryhorenko. He was released in February 1965, and at the end of that year, he was again forcibly hospitalized for participating in the preparation of the “glasnost rally” in defense of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel. He was released in July 1966 at the request of Amnesty International, whose delegation was in Moscow at the time.

Bukovsky was one of the organizers of the demonstration on January 22, 1967, on Pushkin Square. Four days later, he was arrested and sentenced to three years in the camps. He did not plead guilty. Bukovsky’s final statement at the trial was circulated in samizdat.

Upon his return to Moscow in January 1970, Bukovsky gave several interviews to Western correspondents in which he spoke about political prisoners subjected to psychiatric repression. Bukovsky was summoned to the prosecutor's office, where he was warned that if he did not stop transmitting information to the West about human rights violations in the USSR, he would be prosecuted. He was placed under overt surveillance. However, Bukovsky continued to collect and publish materials in the West about the use of psychiatry in the fight against dissent in the Soviet Union.

In 1971, Bukovsky compiled a collection of documents dedicated to Soviet punitive psychiatry, which included materials on people declared mentally incompetent. The collection was published abroad, where it received widespread attention.

In March 1971, Bukovsky was arrested for the fourth time. The arrest was preceded by an article titled “The Poverty of Anti-Communism” in the newspaper “Pravda.” In the publication, Bukovsky was called a malicious hooligan engaged in anti-Soviet activities. The trial took place in January 1972. Bukovsky was charged with disseminating anti-Soviet materials, transmitting them abroad, and making slanderous allegations that healthy people in the USSR were being placed in prison-like psychiatric hospitals. Bukovsky was sentenced to 7 years of imprisonment (serving the first two years in prison) and 5 years of exile.

While imprisoned, he co-authored with his fellow inmate, psychiatrist Semyon Gluzman, “A Manual on Psychiatry for Dissenters”—a kind of textbook for those whom the authorities tried to declare insane.

On December 18, 1976, Bukovsky was escorted under guard and in handcuffs to Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport and exiled to Switzerland. This was the result of a diplomatic maneuver in which, simultaneously with Bukovsky’s release, the leader of the Chilean Communist Party, Luis Corvalán, who had been arrested after Pinochet came to power, was released from prison and exiled from Chile.

Bukovsky settled in Great Britain and graduated from Cambridge University with a degree in neurophysiology. He wrote a book of memoirs. He was a member of the editorial board of the journal “Kontinent.”

Bukovsky took an active part in various campaigns for the defense of human rights. In particular, he was one of the organizers of the campaign to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics. From 1983 to 1988, he made great efforts to secure the release of Soviet soldiers captured in Afghanistan.

“He always did more than anyone else, as the intensity of his practical activity was immense… He functioned with colossal strain, continuously, and was a true professional,” said Anatoly Yakobson about Bukovsky.