BALYS GAJAUSKAS ON VASYL STUS

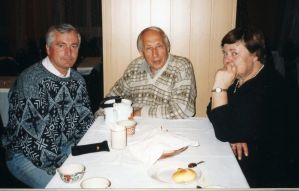

From October 3–6, 2000, the Perm “Memorial” organization invited me to participate in the conference “Museums and Exhibitions of ‘Memorial.’” At a hotel in the town of Chusovoy, Perm Oblast, I met my former cellmate, the Lithuanian Balys Gajauskas, and his wife, Irena Gajauskienė.

A partisan, Balys Gajauskas served 25 years of imprisonment (1948–1973). He was arrested for a second time on April 20, 1977, and on April 12–14, 1978, he was sentenced for so-called “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” to another 10 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile, having been declared an especially dangerous recidivist. In captivity, he mastered a great many languages. He could read practically all European languages. He lamented that he had grown rusty in Korean, Japanese, and Chinese, as he hadn’t read anything or spoken to anyone in those languages for a long time. He was released from exile on November 7, 1988. He was elected a deputy of the Seimas, headed the commission for investigating KGB activities, and served as Lithuania's Minister of Internal Affairs. This, after 37 years in captivity!

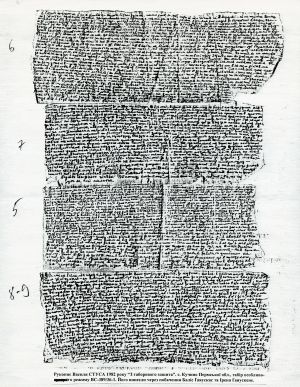

I showed Balys and Irena a photocopy of Vasyl Stus's manuscript, which is published in books under the title “From the Camp Notebook.” Irena said:

“Why, I’m the one who carried that out...”

Balys Gajauskas explained. “In the first half of 1983, Vasyl Stus and I were in cell 20. I was scheduled for a visit. I took these little sheets from him, rolled them up with my own papers, and hid them. I didn’t know what was on them. And there was no time or opportunity to look. I assumed they were poems. I passed them, along with my own texts, to my wife during the visit.”

Irena Gajauskienė: “The little package was as thin as a knitting needle because the paper was very fine. I used to buy that kind of paper for Balys at a pharmacy in Kaunas.”

“It was in the summer of 1983—in June or July. After the visit, I went to Moscow and gave the package to the Moscow dissidents. After arriving home, I wrote a letter to Balys to say that all was well with me, because they could have searched me on the train. The women from Moscow who went for visits were searched both before and after. But for some reason, they didn’t search me.”

“That, by the way, was our last visit in Kuchino. The following year, in response to my application asking when I could have a visit, I received a reply that for a violation of the camp regime, Balys was deprived of the right to his next visit and to a parcel. Then Balys’s mother fell ill and died a month later. And Balys was in a punishment cell. For three years after that, Balys was not allowed any visits or parcels.”

B. G.: “I always put my last name, the date, and the place under my articles. My last article, written in Kuchino, was called ‘Occupied Lithuania’... No, the last one was ‘On the Condition of Workers in the Soviet Union.’ It was very long: 50 of these little sheets. I wrote it over a very long period because it was very difficult to write. Sometimes weeks would go by without any opportunity to write anything down. They were constantly looking through the peephole. And you had to hide from some cellmates. I had the entire article in my head, down to the smallest details. After that article, I thought: ‘That’s it, I’m not going to write anymore. I can’t stand this tension anymore. The risk is too great.’ Then two KGB agents from Lithuania arrived and showed me that article, printed in a foreign journal. ‘Do you know what this is?’ they asked. ‘No, I don’t.’ ‘Take a look.’ ‘So what about it?’ ‘You know very well that this means a new sentence.’”

“I did not disown the article, but I did not confirm my authorship either. I barely spoke with them at all. But after that, I finally decided that I would not write again until the end of my term. After the publication of that article, I was repeatedly put in a punishment cell, and in March 1986, with less than a year of my sentence left, they attempted to kill me. At the time, my cellmate, a former common criminal and now a political prisoner named Borys Romashov, struck me several times on the head and in the heart area with a screwdriver. I fell under the table and the screwdriver went in at an angle—it didn’t reach my heart...” (Balys Gajauskas then expressed his hypothesis that the KGB might have sent Romashov to kill Stus. He could have done this out of hatred for Stus, from his own chauvinistic convictions, for selfish reasons, or due to his psychological issues).

“If it's just one slip of paper, I can swallow it in case of danger. But sometimes they would suddenly transfer me to another cell—and the papers were left behind. I still remember where I hid them in the toilet during the barrack-style confinement. I checked yesterday: those holes have already been filled with concrete. They obviously didn’t find my papers; they must have just been doing repairs.”

V. O.: “You know, I found one of my papers. It’s not very important: it was Vasyl Stus’s translation of Kipling’s poem ‘If,’ which I had copied out by hand. I had copied the text from Ivan Polishchuk (he called himself Yevhen). On the morning of December 8, 1987 (I was already in barrack-style confinement), I saw a whole cloud of *menty* swarming into the zone from the guardhouse. And I had this poem with me, which I wanted to learn by heart. So it wouldn't be confiscated, I quickly went around the corner near the entrance to the bathhouse and slipped the paper under the roofing felt that covered the insulation for the heating pipes. It was an addition less than a meter high. That day, they conducted a ‘general shakedown’ in the zone, and 18 of us, the ‘especially dangerous recidivists,’ were taken away in *voronoks* to another zone 70 km away, at the Vsekhsvyatskaya station. Why? The name ‘Kuchino death camp’ had become too much of a fixture in the Western media. On that very day, Gorbachev was meeting with Reagan in Reykjavik, and he needed a half-truth, at least for one day: ‘But they are no longer in Kuchino.’”

“So, on August 31, 1989, as a free man, I visited that zone. We had come to take the mortal remains of Oleksa Tykhy, Yuriy Lytvyn, and Vasyl to rebury them in Kyiv. They did not allow the exhumation then, saying: ‘Unfavorable sanitary and epidemiological situation.’ But we did enter the zone. It was abandoned: the gates and doors were open, and the local population was carting away whatever they needed: floorboards, glass, slate roofing... I remembered my slip of paper, stuck my hand under the roofing felt, and pulled it out. The text had faded a bit, but it was still legible. I still have it.”

B. G.: “Yes, Stus translated Rilke. He threw away the drafts, of course.”

V. O.: “I was in the same cell (No. 18) with Stus for a month and a half, in February–March of 1984. He once told me: ‘I had two or three channels out of here.’ That is, he managed to send information out of Kuchino two or three times. Now I know that one of those times was through you. That little package made its way to Germany, to Volodymyr Malynkovych, a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, who was working at Radio Liberty at the time. He passed it on to Nadiya Svitlychna in New York. She later told me that she was able to read the text then even without a magnifying glass, although the handwriting was very small. Now I know who performed this service.”

I. G.: “In 1978, along with Balys’s documents, I smuggled a text by Ivan Hel out of the Sosnovka camp in Mordovia.”

V. O.: “He wrote the book *Hrani kultury* [Facets of Culture] there. Perhaps that was it.”

I. G.: “That was the first time. I brought Balys clean, thin paper then. And each time I would bring clean paper and take out papers with text on them.”

B. G.: “It was easier in Mordovia. Many people got information out from there. But that’s precisely why they moved us from Mordovia—because there were channels. In 1980, when we were being moved from Mordovia to the Urals, someone asked the camp chief, Nekrasov, where they were taking us. He replied: ‘We’re taking you to a place where you won’t be able to write.’”

…So, Stus wrote even where writing itself was a crime. Especially something like “From the Camp Notebook.” These 16 scraps of paper take up 16 pages in the book, but their explosive power was such that it also destroyed Vasyl himself. I believe that one of the reasons for his death was the appearance of this text in print in the West. (See: Vasyl Stus. *Vikna v pozaprostir* [Windows into Another Space]. Kyiv: Veselka, 1992, pp. 208–226; Vasyl Stus. *Tvory* [Works]. Volume 4. Lviv: Prosvita, 1994, pp. 485–502).

The second reason was the move to nominate his work for the Nobel Prize. The Kremlin gang knew that this prize, according to its statute, is awarded only to the living, so they dealt with the potential laureate beforehand in the traditional Russian manner: “*Net cheloveka – net problemy*” (“No person, no problem”)...

Vasyl Ovsienko. “The Death of Vasyl Stus.” *Dzerkalo Tyzhnia*, no. 34 (409), September 7, 2002, p. 12; Vasyl Ovsienko. *Svitlo Liudei: Memuary ta publitsystyka* [The Light of People: Memoirs and Essays]. In 2 vols. Vol. 1. Compiled by the author; cover design by B. Ye. Zakharov. Kharkiv: Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; Kyiv: Smoloskyp, 2005, pp. 291–294.

Former cellmates Vasyl Ovsienko and Balys Gajauskas with his wife Irena Gajauskienė met at a hotel in the town of Chusovoy, Perm Oblast. October 2, 2000.

The manuscript of Vasyl Stus’s “From the Camp Notebook,” which the Gajauskas family brought to freedom in 1983.