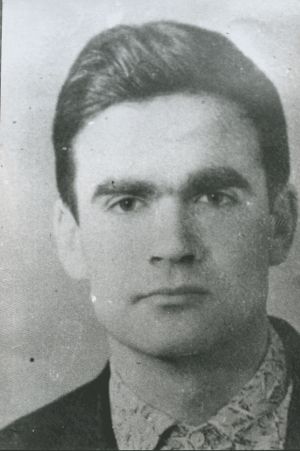

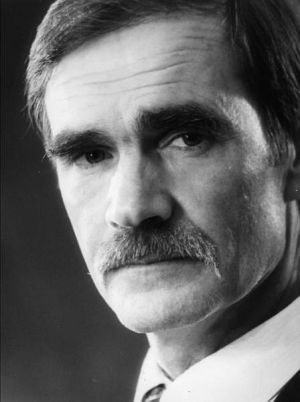

Vasyl LISOVYI

MEMOIRS

Note. Dear readers, I am presenting a corrected and expanded text of my Memoirs. The corrections and additions were especially significant in connection with the declassification by the Security Service of Ukraine of documents related to the “Block” case. I express my gratitude to Vasyl Ovsiyenko for his careful proofreading of the text. As for its content, full responsibility lies with me. August 8, 2010. – V. Lisovyi.

Contents

Chapter I. The Beginning of the Road.

1. The Land.

2. History.

Chapter II. The Ruin of Daily Life. Fragments of Tradition.

1. The Ruin. The Fate of My Brothers and Sisters.

2. Stories, Myths, Customs, Religiosity.

Chapter III. School.

1. Bezradychi School.

2. Velyka Dmytrivka School.

Chapter IV. The University.

1. The Start of My Studies. Daily Life. The “Buza.”

2. Teaching. Self-determination.

Chapter V. Ternopil Medical Institute.

Chapter VI. Postgraduate Studies. The Institute of Philosophy.

1. Postgraduate Studies.

2. Teaching at KSU. The Institute of Philosophy.

Chapter VII. The Spread of Samvydav. Coming out from the “Underground.”

1. The Reproduction and Dissemination of Samvydav.

2. The Arrests of ’72. Coming out from the “Underground.”

Chapter VIII. The Investigation.

1. The Investigation.

2. Ideology and Ethics. Repressive KGB Technologies.

Chapter IX. Camps and Exile.

1. Mordovian Camps.

2. Perm Camps.

3. Exile.

Chapter X. The Exhaustion of the Leviathan.

1. The Museum of the History of Kyiv.

2. Teaching.

3. The Ideology of “Perestroika.” Helsinki-90.

I dedicate this to the memory of my mother

Psychoanalysis has offered us a regressive movement toward the archaic; the phenomenology of spirit offers us a movement in accordance with which each figure finds its meaning not in what precedes it, but in what follows it: in this way, consciousness breaks free of itself and directs itself forward, toward a future meaning...

Paul Ricœur, The Conflict of Interpretations.

Chapter I. The Beginning of the Road

1. The Land

The place. South of Kyiv, the Dnipro River immediately recedes from its high, steep banks, forming a wide lowland. Scattered within it are villages, as if they had fallen from the bag of a wandering deacon on his way to Kyiv: Mryhy, Koncha-Zaspa, Kozyn, Pyatykhatky, Tsenky, Ukrainka. When you travel south on the “new” of the two asphalt roads toward Obukhiv, the steep banks of the Dnipro’s right bank disappear from the horizon near Novi Bezradychi: here, the lowlands form a branch—a wide channel for the now very narrow Stuhna River. The high, steep banks of the Dnipro turn sharply west in the village of Novi Bezradychi: this turn, high and steep, is a place from which the expanse of the Dnipro lowlands opens up. I admired this expanse in my youth, and after returning from exile, my wife and I climbed this height—this time, the high-voltage towers of the Trypillia Thermal Power Plant floated like a mirage in the sky. When I was first told that Yushchenko had built a dacha for himself in this place, I initially thought he had managed to perch it on the slope to have a view of the vast space. Seeing it below, at the foot of the slope, I was disappointed. Although how would you even place it on such a steep slope?

Below this high bend, on the side of the Novi Bezradychi road, was the homestead of my mother’s parents—my grandfather, Myron Tkachenko, and my grandmother, Paraska (in the village, they called her “Baba Pelehachka”). She had a loom and, for that time, a lot of land, not only a field but also a meadow near the homestead, beside the swamp. The homesteads of the Tkachenkos (my grandfather Myron’s brothers) were located nearby, right here on the corner at the foot of the hill.

I know that my grandmother Paraska was from the village of Pidirtsi: when I took a job as a teacher in 1987 at the Velyka Dmytrivka secondary school, from which I had once graduated, it turned out that the house my wife and I bought in Pidirtsi was right next to the yard where my grandmother had spent her youth.

Paraska and Myron had a large family: four daughters (Fedoryna, Vasylyna, Priska, and Olena) and two sons—Tymish and Petro. The sons were drafted into the army for the First World War, and both returned wounded. Tymish’s wife, Marusia, was pursued by misfortune (the memory of this was preserved in our family). As soon as the family went to bed, whistles and the cracking of a whip would begin in the house: something was driving Marusia out. They moved, but the whip’s crack followed Marusia to the new house. Such stories about the actions of mysterious forces, particularly *domovyks* (house spirits), were still a living part of rural ethnoculture in the postwar years. For a long time, they spurred the imagination and the idea that behind the visible, external reality, there lies another, invisible one.

Grandmother Paraska’s family was unlucky. Grandfather Myron and both of his sons died early, and the entire household rested solely on the hard work and energy of Baba Pelehachka. After her husband’s death, she not only managed to maintain it but to improve it. My mother, Yefrosyniia on her birth certificate (though she was called Priska), must have inherited from her mother the energy and persistence she showed in the struggle for her children’s survival.

My childhood and youth were spent in Tarasivka—a hamlet of the village of Stari Bezradychi. Not far from Tarasivka, towards the neighboring village of Neshcheriv, a small field rises gently to a summit called Bili Horby (White Hills). Today, both the field and the hills are covered with a pine forest, which we, schoolchildren of the postwar years, were just planting. In my childhood, there were no trees on the White Hills: we took white sand from them to decorate graves. These hills signify an important moment of self-determination in my life. In my last year at the university, it was on these hills that I made a decision that ended my vacillations: with it, I “affirmed” my choice between good and evil. Specifically, this meant for me the defense of Ukrainian cultural identity against its destruction. I needed this ritual of “affirmation” as a sign of certainty, as the finding of an important point of reference for thought and action. I think that with this romantic gesture, I was trying to assure myself that my choice was final. Later, I expressed it this way:

Змиритися з приниженням народу,

забути всі духовні заповіти,

це означає також дати згоду

на смерть твою, Вкраїно-дивоквіте.

Не знехтуй покликом сумління: як зумієш

втішатися і сонцем і землею,

коли байдужістю своєю дати смієш

із того квіту вирвати лілею.

I cannot say with certainty how much I then understood the simplicity of the ordinary opposition of good and evil and the difficulties associated with unmasking evil’s disguises. At least I understood the complexity involved in choosing the means to fight evil. And that among these means, the justification of “friendship” with evil for the sake of overcoming it is a great temptation. The plan to “outsmart” evil often makes a person a part of that evil. A broader view is also possible: how many good undertakings, good ideas, and slogans have been devalued or even turned into evil by those who joined the movement and interpreted the ideas and slogans. A great deal of blood has been shed in the name of God, including the Christian God, with his commandment “Thou shalt not kill.” Reflections in this direction led me to the conclusion that special attention must be paid to how individuals and groups of people in specific situations interpret and use inventions, ideas, slogans, and theories. I later called this approach “contextualism.”

* * *

The beginning of the road. The Stuhna is the river of my childhood: in spring and sometimes even late autumn, it would overflow its banks and spread wide; the word “flood” still echoes in my memory with the roar of its spring waters. It was beside this narrow, chronicle-mentioned river that Tarasivka was nestled. It had only two streets. They ran in the narrow space between the Stuhna, with its low, marshy bank, and the oak grove, located on stepped slopes that rose to the south, towards Obukhiv. And the village of Stari Bezradychi (like Novi) huddled against the steep slopes that, having turned west from the Dnipro, stretched along the Stuhna basin. Some houses were scattered below on the banks, others on the slopes and gentle hills. These clayey slopes and hills, overgrown with matrimony vine, with their chasms, attracted us schoolchildren: we imagined they concealed some secrets. This corner of the land on the right bank of the Dnipro near Kyiv does indeed have a long memory: Trypillia, Pidirtsi, Stuhna, and even Stari Bezradychi (with its ancient settlement) are known to every historian of Ukraine. This, of course, is not the only place in Ukraine with a long memory. In the world, many lands have a much longer one. But this land between the Stuhna and the Dnipro spoke to me from childhood: its word was the first.

This is the place that marks the beginning of the Road. The Road on which village girls and youths set out with a “rushnyk.” The rushnyk, celebrated in song by my fellow countryman and poet, not only symbolizes the road but above all the connection to cultural tradition—that most precious gift we can receive from previous generations. Childhood impressions are for us the “ring of youth,” the “white candle” that will burn “in the depth of nights.” They cannot be recreated in their original sense: they beckon us with their play, inviting us to unravel their hidden meanings. They are thrown into our souls as a theme for improvisations.

Ти мій забутий сон, моє видіння,

відкритим світом перше милування,

забутих мрій чарівне колисання,

пречистих луків золоте світіння.

A person’s life resembles a stream that leaves behind traces—impressions: they change the angle of vision and the color of the ray in whose light we see our former experiences. And this means a continuous rethinking in the flow of our experience. And yet, the play of meanings in what was previously experienced retains its charm for us. Moreover, their call inclines us to choose and makes life dynamic. This provides the key to understanding these memoirs: they are not confessional, “regressive” (to use Paul Ricœur’s term). They are not aimed at uncovering hidden desires behind flashes of insight, illuminations, or idealizations. As “true” reality. Rather, on the contrary, in our past impressions and experiences, we cherish hints of meaning that we can catch and articulate in a certain semantic perspective.

It is also worth mentioning the attitude toward the past from the viewpoint of its heterogeneity. Since in these memoirs the imperial and communist ideology and the corresponding political system are predominantly objects of negative assessment and condemnation, I would not want this to lead to an underestimation of those elements or practices that, even in our modern understanding, deserve a positive assessment. After all, this part of the experience can be used in modern cultural and state-building. Provided the corresponding will exists. How these elements coexisted or were connected with the ideology and political practice of that time is another question.

* * *

The lands of the forest-steppe are far from being as fertile as the black-earth steppes that widen ever further south of Obukhiv. The soils of the forest-steppe are diverse—sandy in places and, therefore, poor. In the vast Dnipro basin, these are mainly sandy deposits, often adjacent to marshy lowlands, sometimes covered with a layer of peat. Tarasivka is located on just such a sandy slope, which gradually rises from the banks along the Stuhna to the south, turning into a sandy field near Obukhiv. Thus, the vegetable gardens on the Upper Street were mostly sandy and poor. They required fertilizer and watering. On the lower street of Tarasivka, the lowland part of the gardens, which gradually transitioned into the swamp along the Stuhna, was called the “berehy” (banks). The soils at the end of the gardens, in the berehy, were more fertile. For me, berehy is not just lowland earth, but morning fogs and the sparkling of dew on the meadows, evening frog choruses, the breath of moist wind saturated with the smell of grass, cucumbers, and beet tops.

In spring, you couldn’t get from Tarasivka to the seven-year school in Stari Bezradychi by taking a shortcut across the footbridge: you had to go over the bridge—along that old, “upper” Kyiv road, which was paved only in the mid-90s. In the years of my childhood, this road was paved with gray stone only in small stretches. The image of the “beaten” path leading into the wide world is linked in my memory with this gray stone. A beaten path in my imagination (and in Ukrainian folklore as well) is a path into a world full of dangers.

On the hills and steep slopes where Novi and Stari Bezradychi were nestled, cemeteries had long been located. On our way to school, we passed a hill that held a former cemetery in Stari Bezradychi: part of it had collapsed; on a cliff hanging over the road, a skull gleamed white against the yellow clay. Like a sign that reminded of the generations that walked these paths. I thought I could hear their footsteps and voices: “put your ear to the ground—they are coming.” Further west, along the bed of the Stuhna in this ridge of hills, one stood out, separate from the others, with almost sheer slopes—the Bezradychi ancient settlement. The ancient settlement is a sign of resistance: standing on its “ramparts,” we “saw” Tatar horses rushing from the south, “heard” their neighing and the shouts of the settlement’s defenders.

* * *

Clay. The clayey hills and slopes attracted us, the schoolchildren, and some of us, including the author of these memoirs, instead of sitting in school on warm days at the end of spring, explored the yellow clay gullies and caves. The metaphor of clay, the symbol of clay, and all the fluidity of this symbol’s meanings were later superimposed on these my first impressions. The symbol of clay in the most diverse semantic shades—including in the sense of St. Augustine, who in his “Confessions” speaks of the “clay of my being”—is one of the important ones in the European cultural tradition. It also found its artistic interpretation in Ukrainian poetry (Tychyna, Drach). The feeling of the dampness and amorphousness of clay in myself and in my surroundings became the source of my appreciation for form: Berdyaev’s expression about the formedness of the Western person and the amorphousness of the Russian soul (as a result of the “boundless expanses”) reminded me of the sources of my early, still only subconscious, opposition to this uncertainty and amorphousness. The brokenness of people, their crippled state (physical, and especially spiritual), their lack of will—I began to think through the metaphor of clay.

This is a branching theme of the Mediterranean-European philosophical tradition, marked by pairs of oppositions: matter-form, potentiality-actuality. On the one hand, formless passive matter as nothing, as only a possibility of being, and on the other—active form. God as the source of all meanings-forms and human action as the source of meaning. In the theological version, the infinite and undefined spiritual substance, a particle of which we carry within us as a gift from our Creator, is still only the ability to “hear” the word of God as the source of meaning. The gift of God or the grace of God is twofold—as our capacity for a meaningful life and as the Word—the path to meaning. This Word is called the Law of God, as a prototype of any law created by people. Both components—the gift as an ability (as a possibility of spiritual life) and the gift as the Word or Law (without which the ability remains something undefined)—are equally important. This indicates that in the well-known distinction between grace and law, initiated in the Ukrainian intellectual tradition by Ilarion (despite possible different interpretations of this distinction), the main direction of my philosophical “style” lies in shifting the emphasis to the formation of personal and social life, to institutions, including the Law. Although the spirit (or Sophianism) must animate the law, without law, without embodiment in earthly forms of life, the spirit is inactive.

Culture as a set of institutions that form a person, and meaning-creating action and will as the source of all forms and re-formations—this is an emphasis more on action and creativity as opposed to mere potentiality. For grace is often understood as only an undefined spiritual substance in its infinite attributes. At least this shift of emphasis to action is safe until the threat of thoughtless activism appears. Or another threat: when the material being “formed” is thought of as mute, and reason as the form-creating factor, as the source of all meanings.

The theological version just outlined corresponds to a secular one. Man possesses a natural “gift,” the ability to acquire language (and, therefore, meaning), and more broadly—culture. On the other hand, man, in accordance with his nature (as an inferior “animal”), needs value—that is, a rule, a law. The “gift” of nature in this secular version remains only a capacity, a possibility of becoming human. This possibility is realized through the assimilation of another gift—cultural tradition as something passed down to us. However, any “matter” is not entirely passive: it has its sources of activity and its own “memory.” Therefore, any “forming” is only a “re-forming.” If instead of the word “forming” (as too mechanical) we speak of sense-making and re-interpretation, then the hint of memory points to an attentiveness to the meaning that tradition contains within itself. Without “hearing” what it says, we impoverish the resources of our creativity—including in the emergence of new meanings and values. In short, “clay,” as a symbol of matter, is not entirely mute.

Perhaps my youthful impression of uncertainty and amorphousness can be understood only by taking into account the spiritual situation of Ukrainian life at that time. I have in mind the fact that the fragments of tradition contained in the social environment were not included in a new meaning-creating action. In order to become the basis of those social values that would be able to withstand the onslaught of absurdity and chaos. Later, in B.-I. Antonych, I found a resonance with this impression: “A reverie—not quite a reverie, sadness—not quite sadness. On this land, it is a tragic papilloma.” Antonych here only picked up the theme, initiated by Shevchenko, of the sleep and future awakening of the robbed. Robbed primarily culturally and spiritually: having allowed themselves to be robbed in their enslavement, in their inability to defend themselves with action, the awakened manifest their awakening in anger and rebellion.

* * *

The oak grove. In the years of my childhood, Tarasivka had (and still has) two streets: one was called “Upper,” the other “Lower.” During my time in the camps, one of them was named “in honor of Taras Shevchenko,” the other—“in honor of Alexander Pushkin,” for the sake of strengthening the friendship of peoples. The streets with two rows of houses on either side, covered in the post-war years mostly with straw, mostly built with wattle and daub walls (perhaps only the vestibules here and there were log-built). The yards next to the houses were overgrown with knotgrass, plantain, and grass, enclosed by woven fences, lathes, and occasionally by board fences. In front of the house were flowers—“virhenii” (dahlias), cosmos, peonies, lovage. Around the houses were orchards—cherries, plums, pears, apples. Beyond the yards and orchards were vegetable gardens (after the war, every household that worked on the collective farm was entitled to 0.6 hectares).

The gardens of the Upper Street ended almost at the ditch that separated the oak grove from the gardens. A path from our house, running through the middle of the garden, led through the ditch into the oak grove. The oak grove—a community of oaks, pines, pears, birches, hazel, hawthorn, “baiborys”—was part of my worldview in the days of my youth. In early spring, there would be a day when a barely audible breeze of reviving branches would reach you, and your soul would respond with an awakening of hopes:

Дібровонько, знов чується твій поклик,

передвесняні шепоти-зітхання,

гілок до гілок перший дружній доторк,

забутих мрій таємне оживання.

Meanwhile, the harsh, even gloomy rustle of the trees in autumn brought thoughts and dreams down to earth: like all living things, one wanted to find shelter and warmth in some refuge. The pine forest evoked different moods: the forest between Novi Bezradychi (the hamlet of Pisky) and Kozyn was called a “bir”—it still stretches in a wide band towards Pidirtsi. I was captivated by the image of broken pines in a famous poem by Jānis Rainis (translated by Dmytro Pavlychko), but the motif that the pine forest instilled in me was not proud defiance, but the breath of eternity:

Твій шум, твій сум, стоїчний, споконвічний,

гук пралісу, віків незмірна велич,

в них приспіву звучить мотив трагічний

над гамором щоденним міст і селищ.

From my house, I would walk through the garden onto forest paths, along which, in my student years, I would set out on my solitary journeys of reflection (in winter—on skis). These journeys became one of the sources of the motif of solitude. Solitude is a salvation from the fatigue whose source is the human world. To this day, every Ukrainian intellectual who realized that the nation’s existence depends on his own choice has resisted and continues to resist that looming “not to be.” There is no escape from this: because “we are a handful. A tiny flock.” Now, admittedly, we are no longer just a handful, but a minority among the entire mass of the intelligentsia (which is still “undecided”). An intelligentsia that lacks a position and will. Often, the soul seeks salvation in turning away from this incessant resistance, from this confrontation. To turn away for a while, just to hear the rustle of trees and the breath of eternity. Solitude is a good medicine, but a temporary one.

* * *

For me, a village boy, the forest was also a place of work. For some time, we were allowed to graze cows there. It was not easy to watch over them among the trees, to prevent one from straying from the herd and wandering into someone’s garden. According to accepted custom, the herd was grazed in turns by two shepherds. After the war, there were two such herds in Tarasivka. In Tarasivka, as in other villages in the postwar years, communal lands (the banks along the Stuhna, pastures) where the herd could be grazed were still traditionally preserved for some time. Then (in the 60s), the policy was to take these pieces of land away from the people. This absurdity went so far that people would take their cows on a lead and walk them around on the field boundaries.

The forest was a place for getting firewood. The residents of Tarasivka, most often women, would take rakes and cloths and go to the forest to rake up pine “needles.” Or they would go with baskets and sacks to collect pine cones. Another method: they would take long lathes with metal hooks attached to the top (these lathes were called “kliuchky”), break off dry branches, tie them with rope, and carry them home. From my earliest childhood years until I finished high school, I witnessed a secret war between the forester, who for some reason forbade breaking branches and even raking needles, and the women, who stubbornly refused to sit in a cold house in winter. But the most serious crime, for which one had to pay a large fine, was cutting down trees—even dry ones. Men did this: sometimes they cut them even in daylight, but carried them in the evening or morning twilight, or even at night. The forester could conduct searches and, if he found the stolen wood, could impose fines.

Before the war, a tragic story occurred in Tarasivka during one of these searches at my uncle Anton’s. I don't know the details, as no one talked about it afterwards. In our family, they spoke about it reluctantly: apparently, the uncle, in some conversation with the forester, probably in response to some of his threats, said that if he dared to come to him with a search, he would not leave his yard. But he ignored this warning, and indeed he did not leave—he was carried out dead. Uncle Anton hid somewhere after that, later appeared “with a confession,” and was sentenced to many years in prison. No one in the village or our family justified Uncle Anton's act. But it is very likely that my uncle, who had a pronounced sense of his own dignity, wanted to feel like a master in his own home. Since, as I was told, he had warned the forester, this event has the features of a tragedy in my imagination: in my modern understanding, it has acquired symbolic meaning. It is the last and desperate attempt of a Master to protect the last island of his independence—his home. This later inclined me to sign my “Letter to the Deputies” with the pseudonym “Anton Koval.” But from Uncle Anton’s grandson, I heard a clarification of my story, after this chapter was published. From it, it follows that the forester, whom my uncle did not allow to conduct a search, hit him in the chest and he fell. In response and in anger at his humiliation, my uncle grabbed an ax and struck him. In this case, we have what is legally defined as exceeding the means of defense of oneself and one’s home from illegal entry. And this is indeed true: at that time, no legal grounds were presented for conducting a search in a village house and yard.

Like other children, I carried pine cones and needles from the forest. The last time, I brought enough needles to last the whole winter for my mother, who was left alone. This was after graduating from the university, when I was a philosophy lecturer at the Ternopil Medical Institute. But from the age of about twelve or thirteen, I was forced to get firewood by climbing high into the trees with a “nozhovka” (a small saw) in my belt and cutting off dry branches. Women and children had completely gathered all the dry branches that had fallen to the ground, and had also broken off what they could reach on the trees with long “kliuchky.” I had to climb high. It was risky: dry branches, rotten on the inside, were treacherous, as were pines with their slippery, mica-like bark.

Later, when I was involved in distributing samvydav and risking the loss of the opportunity to do intellectual and teaching work (and subjecting my sick mother to unbearable anxiety), I mentally returned to these high-altitude exercises of mine. This readiness for risk, common to a part of my generation (the “sixtiers”), was consonant with the image of the alpinist in the famous song by Vladimir Vysotsky. The height at which I held on by some miracle, at the cost of a superhuman effort, became a recurring dream for me during my postgraduate years (until my imprisonment). In this dream, I was holding onto the cornice of a high-rise building on Maidan Nezalezhnosti (for some reason located opposite the stairs leading to the October Palace): my legs were up, my head was between my hands with which I was holding onto the cornice, and from a height of a 10-15-story building, I saw the gray cobblestones below.

* * *

To the east of Tarasivka, slightly downstream of the Stuhna, there was a swamp called “Hoshchiv.” It remains in me as a picture of the life-giving fermentation of the earth's juices and herbs—a fermentation that “creates the pre-forms of life.” Mostly, on the eve of Trinity Sunday, children would pull “tatar's herb” from the silty bottom of Hoshchiv, knee-deep in water (that's what they called calamus in the villages near Kyiv—elsewhere, it is called “tsar-herb” in some steppe villages).

In the yard near our house grew two large, spreading wild pear trees. The trees, bushes, and flowers cradled our house in their green palms, like a bird's nest. My years before finishing secondary school were spent in this green luxury.

My “little motherland,” speaking of nature, is not so much the Kyiv region (as its borders are rather formal) as the forest-steppe: its diversity—hills, ravines, gullies, banks, meadows, swamps, sand deposits, fields, oak groves, pine forests. It seems to me (or rather, I would like it to be so) that nature is somehow connected to my way of thinking, which I began to favor in my last years at the university. I mean my sympathy for analytical philosophy: an appreciation for distinctions, clarifications, semantic nuances, contexts—as opposed to the general, the general idea or metaphor.

The main part of my attempts (more attempts than achievements) was aimed at erecting a structure that was well-anchored to the earth. To move upwards, building step by step, rather than with an instant ascent to the summit. In reality, the metaphorical and analytical styles in philosophy rather complement each other. Sometimes through competition and mutual criticism. It is about the relationship between truths that can only be discovered by reason and those accessible only to feeling, to the “heart” (Blaise Pascal). The first ancient philosophers wrote their treatises in a poetic style. It is true that these styles are not easy to combine in one text, because then a “mixing of styles” occurs, in the words of Yevhen Sverstiuk. In the steppes, where my wife Vira is so drawn (she is from Kaharlyk—also the Kyiv region), poets, followers of Platonic idealism, or theologians are meant to be born. There the sky is too close, it absorbs you: one more moment—and you are flying.

The years of my childhood—the childhood of the generation that went into the “wide world” from the village—had their happy advantages: nature, freedom, noisy children's games on the common, swimming in the Stuhna (where I once almost drowned, saved by one of the village boys), the still-living customs of the people with the charm of myths and legends. But through this profusion of green, through the diversity of the forest-steppe and the poetry of customs, time made its way—the history of the Ukrainian people.

2. History

When one moves from describing nature to the intention of pulling back the curtain on the pictures of history, the hand hesitates. The contrast is too stark, known not only from Shevchenko's poems. It has become like a curse—the age-old suffering of a people amidst the luxury of nature, on this fertile land. For everyone who has tried or is trying to understand Ukrainian history, this is a painful theme. It is bitter to realize that for centuries the people have been unable to take advantage of their own advantage—an advantage that would seem to require so little: to become master in their own house. But for that, the people must acquire an understanding of themselves as a subject of history, develop (through their cultural elite) a basis for their unity, and grasp that their lifeworld (cultural identity) is not just a whim of poets, but the basis of their ability to be themselves. And today, the vast majority has still not grasped these simple truths—truths that other European nations assimilated in the 18th–19th centuries.

For the Ukrainian people, history is something that burst into people's lives like a natural disaster, like a strange and alien force. One can, of course, point to periods of history-making, of erecting a structure that signified a cultural space: when people were capable of both building and defending their “house of being.” It is enough to mention Petro Mohyla and his academy or the cultural renaissance of the first quarter of the 20th century. But for the most part, and over the last few centuries, Ukrainian history has been the onslaught of foreign events and forces that have severed all inheritances, all construction. No space could emerge that was defined by values, where the word “value” (*vartist*), contrary to its immediate etymology, should be understood as related to “guard” (*varta*)—with those symbols that signify cultural identity, with the talismans that protect a people from erosion, from disappearance. Without such talismans, a people becomes clay, kneaded by history, which sculpts monsters and phantoms. On the winds that drive people into obscurity, dazed, homeless, and faceless. And only violence and curses are heard.

Still, in this respect, the history of the Ukrainian people is not an exception. The list of tragedies of other ethnic groups would be too long. But complaining about history and blaming an outside force does not signify a new perspective—an escape from the vicious circle. Neither cutting off a history that “cannot be read without bromine” (because forgetting is not a cure), nor constantly returning to the pain as a final stop, is of any help. Only finding a new life perspective in accepting and honoring spiritual values that would become a component of national self-awareness makes the past a source of modern meaning. Though it in no way justifies the horrors of the past.

As long as a people does not feel the power to make historical choices that depend on itself, as long as it has not filled its present existence with meaning, it will return to the past as something self-sufficient in its hopelessness. Because this past lives in the present. Even today, the existence of some small ethnic groups, even those well-united on the basis of a common culture, may be threatened by mortal danger from stronger foreigners (the Chechens are only the first, but not the only example). But Ukrainians are not a small people who could not defend themselves. Moreover, like other nations that have suffered physical genocide and cultural assimilation in the past, they could become an influential force in international relations in the defense of threatened ethnic groups. And this ethical perspective would give some meaning to the tragedies experienced in the past. It could, if the question of preserving cultural identity (and to some extent, even physical survival) were not still facing Ukrainians today. Even today they are still at a crossroads: should they revive and preserve their cultural identity, or, perhaps, is it better to disappear, if history has so ordained it.

* * *

Collectivization. “Collectivization” (the state's seizure of land from the peasants) led to the best field lands being taken away from people. According to accounts, in 1924, the Lisovyi family—my grandfather Petro and his four sons (the youngest of whom was my father, Semen, and his brothers Musiy, Savka, and Anton)—settled in the hamlet of Tarasivka. So, the Lisovyi family had not lived by the forest before (perhaps they once lived in or near a forest, but no memory of it has been preserved). They moved to Tarasivka from Stari Bezradychi. My father and his three brothers, my uncles, had a certain number of hectares of field lands before collectivization. The forest-steppe, as its very name suggests, besides swamps, forests, hills, and ravines (with cliffs or gullies), also consists of fields that are dotted in larger or smaller patches throughout its varied relief. The brothers probably expected that they would continue to own these field lands—in addition to the poor, sandy lands in Tarasivka where they had moved. After all, it was a good place to live: dry, open, with a view of sunrise and sunset, near the forest... Like many other people, I enjoy feeling that solemn moment—meeting the sunrise and bidding it farewell. A sun-worshipper lives in many of us.

After moving to Tarasivka, my father and his brothers built their houses in a row on the lower street, but before the war (in 1932), our house burned down. The fire occurred when my grandfather Petro was left at home with the children, while my father and mother were at work. Mother was working at the “posadky” (weeding young trees “in the forestry”), and from there she saw the fire. Mother—terrified that the children were left in the house (grandfather Petro was supposed to take the cows to pasture)—ran as fast as she could, probably about two kilometers; not quite reaching the burning house by about two hundred meters, she fell unconscious.

The house where I was born, my parents bought from my aunt Vasylyna (my mother’s sister), whose husband, uncle Hryhoriy, worked in Kyiv when they were building it. My uncle got building materials in Kyiv. And so our house, for that time, looked somewhat better in comparison with others: it was roofed with tin, had decorative architraves on the windows and doors, the windows were double-casement and could be opened, and the doors between the rooms were also double-leaf and decorative. The floor in the house, however, was earthen. But my mother was not satisfied with our new house: it was not built as solidly, it was much colder—in part because it was roofed not with straw, but with metal. Later, we children, with our sick mother, had to suffer in this house from the cold and a leaking roof. It even got to the point where there was nowhere to hide from the water dripping from the ceiling. But this was when my father was gone.

* * *

My relatives. In its fullest composition (with everyone who was alive at the end of 1942), our family numbered eight: my mother, registered on her certificate as Yefrosyniia (born 1904), my father, Lisovyi Semen Petrovych (b. 1904), four sons, and two daughters. The brothers: Petro (b. 1923), Pavlo (b. 1926), Fedir (b. 1933); the sisters: Halia (probably b. 1939, died 1944), Liuba (b. 1942). My mother had two sisters—the elder Fedoryna and the younger Vasylyna. Vasylyna—with my uncle Hryhoriy and their children (son Ivan and daughter Olia)—moved to Kyiv in 1932. My aunt Vasylyna lived with her children (uncle Hryhoriy died in 1936) during my student and postgraduate years in Pechersk, on Nemyrovycha-Danchenka Street (formerly Maloshyianivska). Today, the Kyiv National University of Technologies and Design (formerly the Institute of Light Industry) stands on this site. I will mention this apartment later in connection with the spread of samvydav. I do not remember my paternal grandmother—grandfather Petro’s wife. I have listed our whole family here because I will be mentioning my relatives in various episodes that follow.

The life stories of my relatives, taken together, largely illuminate the dramatic history of the Ukrainian peasantry in the 20th century. They provided me with real types that made it easier to see the cultural structure of rural, and at the same time, Ukrainian existence. My mother, Aunt Fedoryna, and my great-aunt Maryna signify for me a Ukraine unreachable by either the former Russian or the new authorities—a Ukraine self-sufficient in its spirituality, harmony, and customs. This self-sufficiency was apolitical, and therefore limited. But potentially, it contained a force capable, under favorable circumstances, of becoming the basis of a political movement—as it turned out in the years 1917–20. Immersion in ethnoculture and folk Christianity—and hence ethical independence and intransigence, reliance on oneself in the struggle for survival—are the most important features of this world. Indeed, this world was disappearing, the people who carried it within themselves were passing away. In the Brezhnev era, a new type of person began to prevail in society. A person who, for the sake of material benefits, was willing to renounce any ethical principles—just to push closer to the authorities, to the “miserable tidbit.” This was despite the fact that the standard of living had risen. We are witnesses that this process not only continued in independent Ukraine but, to some extent, has even deepened. The word “corruption” has become popular.

* * *

Like other peasants—after the distribution of landlords’ lands and the legalization of this land redistribution—my uncles rushed to farming. Being capable, they acquired machinery: even after the war, I would find its remnants near the house. But my memory has also preserved the striking sight of this machinery, brought to the collective farmyard in Tarasivka (in the valley behind the Tarasivka cemetery). On the hill above this valley stood a windmill; we sometimes played near it. Below, our eyes were met with the sight of this machinery, left to rust under the rain: a graveyard of human hopes.

Rereading and editing this text of mine, I note in retrospect that the sandy hill on which the windmill stood has completely disappeared today. It was dismantled by new builders, mostly “dacha owners,” for their “cottages.” It is known that they mostly enclose themselves with high concrete walls and are not inclined to communicate with local peasants. This is especially noticeable in the villages near Kyiv. And the children of the old-timers mostly tried to move to Kyiv or other cities after the war. The intensity of these relocations was growing: the depopulation of villages in Ukraine is a visible phenomenon. The political system did not give peasants the opportunity to become prosperous farmers on their own land.

And yet, probably until the end of the 1940s, uncle Savka’s “drive mechanism”—a device that allowed horses to be harnessed to turn the axle of a winnower or some other machine—remained in private use. I used to watch the horses walk in a circle in front of the barn, while inside, people were pouring in and collecting the winnowed grain. I don’t recall anyone explaining why this mechanism had not been confiscated. Uncle Anton had an oil press: a huge log with a press for crushing grain. It was located right in the house—in the front room, while a stove for roasting the grain stood in the kitchen. For children, the pressing of oil was an interesting event: if the grain was sunflower seeds (and not false flax or rapeseed), custom allowed the children, unnoticed by the adults, to grab roasted seeds from the stove.

Uncle Anton also kept his smithy. It remained with him until the end of his working life. Sometimes I managed to see him at work—how he manually fanned the forge with bellows. In my younger school years, I also engaged in smithing: in our yard under a pear tree, I would forge toy knives, pokers, sickles, and fire-irons for the girls (my little sister and the neighbor girl)... The war left behind metal. The body of the war appeared in my imagination as a giant green monster, resembling a lizard: it destroyed everything in its path, leaving behind metal, its excrement.

One of the mechanisms that uncle Anton owned was a hand-mill. I don't know what the designs of other hand-mills were (I think they were roughly the same), but it was very difficult to turn the crank to grind even two scoops of grain. On it, as a teenager, with my sick mother, I came to know the price of a piece of bread. In the early 50s, windmills still stood on the hills: one in Tarasivka and probably three were visible to the north, on the horizons, when looking from the low-lying bed of the Stuhna. The movement of their sails beckoned one to fly beyond the horizons. Like some of my spiritually close fellow villagers, I sadly perceived the disappearance of the windmills on the horizons: they were dismantled for firewood. With the same sadness, people perceived the horizons from which the domes of the Novi Bezradychi church had suddenly disappeared (in the 30s) (it had been blown up).

People went to the windmills when they needed to grind a sack or at least half a sack; for this, they had to pay the miller a “mirchuk” (a scoop or two of flour). To grind a small amount of grain (and often there was not much grain), the hand-mill was a lifesaver. The hand-mill belongs to the common experiences of my generation. This was best expressed by Symonenko (as well as some other common experiences and feelings of the rural youth of the post-war generation).

As I recall from stories, there was a threat of “dekulakization” for my father and his brothers. Some person came to their rescue by suggesting the idea that these four Lisovyi brothers, by farming together, had started the first village cooperative. It is quite likely that someone might have actually used this half-truth as an example of the working peasantry's gravitation toward socialist methods of farming. Still, as I can judge from my mother's stories, my father (unlike my mother) initially took a favorable view of the idea of collective farms. And when a temporary “retreat” in forced collectivization was announced (this was connected with the publication of Stalin's article “Dizzy with Success” in “Pravda”), it was my mother who dragged the wagon from the collective farm, and then brought the horse.

Only later did I learn (from literature) about the cooperative movement—the thing that scared the Bolsheviks. Such socialism was a real alternative to the Bolshevik one. Lenin felt the threat from the cooperative movement, and the Bolsheviks rushed to destroy the cooperatives that had begun to print Ukrainian books, establish mutual aid funds, etc. But deceiving the people with socialist phraseology became the main ideological weapon. Yet, at first, this demagoguery did not achieve the desired result: the resistance to collectivization is proof of that.

Perhaps my father really was influenced by that post-revolutionary communitarian socialism? Perhaps so, but of our parents' aspirations and struggles, only echoes reached us, the youth of the post-war generation. It became dangerous to talk about the struggle for an independent Ukraine, the struggle against War Communism, and the resistance to collectivization and dekulakization. The times had changed. The recent past was cut off, it became unreal.

* * *

I never had the opportunity to find out how many people were “dekulakized” in the village of Stari Bezradychi. More interesting to me were the peasants' reactions to this event. Most pitied the “dekulakized” for their hard work and good attitude toward people. Those who in the literature of “socialist realism” personified the type of “kulak” were exceptions. I mean the greedy ones who sought to ruthlessly exploit others (“hired hands”). But the image of the dekulakized—these products of “historical necessity” who were to be punished for the course of history—kept appearing in my imagination:

Корчуваті дуби, згорблені понад шляхом.

Земляки – ви куди? Етап за етапом.

Хіба не було чути свободи дзвону,

Щоб знову від Славути аж до Сибіру гноєм?

Many tragic stories are associated with “dekulakization.” One of them was told to me by my niece Halia Lisova, the daughter of my brother Petro. Halia worked as a nurse in the Zhovtneva Hospital her whole life: she and I have much in common in our way of feeling and understanding the world. She now often lives for long periods in Bezradychi, in her parents' house. She helped me to clarify or add some details to these memoirs.

Here is that story. Yovkhym Zhuk, Halia’s grandfather on her mother's side, owned a windmill and a field on Hora, a locality in Stari Bezradychi. When Yovkhym was told that he had been “dekulakized,” he got up in the night and set fire to the windmill. In the morning, his wife Khymka went outside and saw that their windmill was on fire:

— Yovkhyme, our mill is on fire.

— Let it burn, Khymka, let it burn, – she heard in reply.

Perhaps on the same day, or maybe a few days later, Yovkhym, still in the same state of despair, went to water the horse and at the same time bring water to the house (the well was in Chotyrkiv—the name of the locality). The horse returned, neighing, but Yovkhym was not there. They went to the well and saw him drowned. Only the past knows the truth—whether it was a suicide or an accident.

* * *

The War. To bring some order to this narrative, I will turn to the images beyond which my memory does not reach. No matter how I tried to extract any impressions from before the start of the war from the depths of my memory, only some shadows remained, indistinct, like dreams. More than once I tried to figure out for myself whether the picture in which I (as a small boy, it seems) am walking in the dark and see the glow of a fire on the horizon is a memory or just a dream. And why did this sight surface from the depths of my memory (or why did I dream it) again and again? Meanwhile, the pictures of the war, beginning with the entry of German troops into the village, appear clearly and distinctly in my memory.

I see myself in a small line of boys on the side of the street, along which a column of German troops is moving. I remember saying the word “Fritzes” and immediately hearing a warning from one of the wiser ones among us. From the entry of the German troops into the village (and they, for known reasons, entered without a fight), a picture of the solemn arrival of motorcyclists has remained in my memory. It was precisely these advance units of the German army that demonstrated the greatest contempt for the “natives.” This impression later contrasted with my acquaintance with German culture—German philosophy, poetry, and language (which even today attracts me with its rich root base, and in this is similar to Ukrainian). In reality, this contrast only testifies to what a malignant ideology can do to people.

The attitude of my parents, like most peasants, to the “occupiers” was alienated and cold. Only a few of the peasants entered into any kind of relationship with them, to get, say, some “canned food” or sugar from them. And it could not have been otherwise: they were perceived as foreigners, and their arrogance only increased the alienation. In contrast, the soldiers of the “Soviet” army were perceived as “our own”: and they treated the peasants in the liberated territories as their own. This contrasts with the attitude toward the “liberators” which, in the light of the experience of 1939, the population of Western Ukraine displayed. Of course, the attitude of the ruling elite (including a part of the Soviet army command) towards those who had been in the occupied territory was different. On the other hand, the peasants’ attitude towards “our boys” can in no way be identified with their attitude towards the “Soviet” authorities. For this government from the very beginning waged a continuous war against that Ukraine which, for lack of a better word, I call “underground.”

I call it the underground Ukraine, the one that, despite atheist propaganda, kept icons in the houses, embroidered shirts in its chests, and portraits of Shevchenko on the walls of its homes. It was the basis of the national movement in 1917–1920, it resisted collectivization, it was the object of revenge—for stubbornly existing. For not accepting the proposed substitute, the official Ukraine, one of whose purposes was for the Ukrainian Ukraine to disappear. Later I witnessed how this Ukraine dwindled, as village children, tempted by an easier city life, forgot its history, its legends, myths, customs, and language. Of course, they were helped to forget. Very influential forces are helping to do this even today, updating their technologies and ideologies. And today every thinking Ukrainian faces the choice of whether Ukraine should be or not. I will later recall how I made this choice myself.

The relations of the underground Ukraine with the authorities were external and alienated. I think it could not have been otherwise: if only because of the forced collectivization and the famine of ’33. The peasants could not consider such a government their own. Of course, the German occupation authorities were also perceived as alien. The contempt and rudeness of the Germans were an important reason that pushed people to participate in the partisan movement. One form of violence, the fascist regime replaced with another. What I've said explains the attitude towards the Germans on the part of the peasants in a broader context—in the context of the attitude towards any government that is not their own. Whether such institutions as school, the system of education and propaganda, removed this alienation between the people and the authorities, I will discuss later.

And yet, we children, despite all the horrors, found something new, and therefore interesting, in the war. We got toys—cartridge cases, foil, beautifully designed boxes, tin cans. Some of these toys turned into disability and death for children. Once I also started to unscrew a light-blue “lemonka” grenade. My brother Fedir was nearby and ran to me with all his might and managed to take my “toy” away. These “toys” killed and maimed children for many years after the war. A group of teenagers (among whom was my cousin Mykola, Aunt Fedoryna’s son), while grazing cows in the pine forest, began to do something, probably with an aerial bomb: its explosion was heard in the village, the children were killed.

In 1942, our family grew—a baby girl was born. She was named Liuba. When Liuba was only a few months old, the Germans decided to set up some kind of headquarters in our house. They occupied two rooms—the front room and the bedroom, and all of us had to live in the kitchen. The proximity of the headquarters turned into an unexpected disaster for us. One of the German officers, as soon as little Liuba began to cry, would grab the infant, run out of the house with her, and throw her on the ground. My mother, with a cry of despair, would run out into the yard and pick up my sister from the ground. The repetition of this forced my mother to seek some salvation. She was told that some higher-ranking German official lived with our neighbors; she dared to go and complain about the officer. The reaction was unexpected—the public punishment of this officer, which the neighbors could see. A strange punishment: the officer had to crawl back and forth on all fours for some distance on the road. But even stranger was that he did not seek revenge on us for this humiliation. On the contrary, from time to-time he would give the girl some sweets. Perhaps some words from the senior officer awakened something human in a soul brutalized by fascist ideology.

Some youths and girls who were threatened with deportation to Germany tried to hide. My brothers Petro and Pavlo also hid, as I recall, in caves somewhere near the hamlet of Berezove (a hamlet of the village of Stari Bezradychi). My memory has clearly preserved the picture of a policeman coming to our house. He was cracking a whip against the door and rudely, with a quarrel, demanded that my parents hand over one of the two brothers to Germany. The occupation authorities forced families with youths and girls of the appropriate age to choose one, or even two, for deportation to Germany. Hiding did not help—the policemen knew the composition of every family. My eldest brother Petro was fated to this. In addition, two of my cousins—Natalka (uncle Anton’s daughter) and Maria (my aunt Fedoryna’s daughter)—were also taken to Germany. It is known that those who ended up with German farmers had it easier. It was much worse for those who worked in factories, and later on the construction of defense structures, digging trenches, etc. Petro and Natalka were not destined to end up with farmers.

After Petro returned home, I had the opportunity to get acquainted with the postcards that Natalka had sent to Petro in Germany. Touching these postcards and reading them is one of the special impressions of my youth, impressions both painful and inexpressible. The poetic epistles of this Marusia Churai—with their nostalgic lyricism, illuminated by tragedy—are an image or a shadow that will be with me to the end of my days. Natalka died in Germany, and a premonition of this was present in her postcards. One stanza from her poem-songs has sounded in my memory all my life:

Прощай, любов, прощай, розлука,

прощайте, очі голубі,

прощай, те все, що вже минуло,

щоб не боліло на душі.

It is now impossible to collect the letters of those young men and women, to make public this tragic page from the life of youth torn away from Ukraine. I learned an interesting fact, perhaps unknown to our historians, from my cousin Maria, daughter of Aunt Fedoryna. Some of the youths and girls taken to Germany, after the occupation of East Germany, were not allowed to return home for a long time by the Soviet regime, forcing them to serve the occupation authorities (and strictly forbidding them to tell anyone about this fact). Maria and her husband were not allowed to go home for seven years. Only in the 90s did she dare to talk about this fact.

During the retreat of the German troops in 1943, I witnessed the consequences of our childish, thoughtless actions—mine and the neighbor girl Olia’s (the daughter of Aunt Yivha, whose house was next to ours). Olia would steal some trifles from the Germans, pieces of soap, for example. She would give these small things to me, and I would hide them. My memory preserves a picture of a German with a submachine gun pointed at the girl and Aunt Yivha on her knees, sobbing and begging. I also remembered another event. When the headquarters had already left our house and all things had been taken from the house, some German ran in, tore a portrait of Hitler from the wall, and said something like this: “Stalin-Hitler—duts-duts,” tapping himself on the forehead. I wonder if this person, forced to become a cog in the senseless machinery of war, survived.

* * *

I remember quite well the entry of the Soviet troops into the village. They entered with a fight. We (my mother with us children) hid in Uncle Musiy's cellar during the battle. Only Grandfather Petro was not with us. He must have been grazing the cow in the forest so the Germans wouldn't take it during their retreat. Grandfather Petro—a tall, sturdy, strong man—had a strange habit of ignoring warnings. During some shellings or bombings, when we hid at least in the space under the stove, he could lie peacefully on top of the stove. One got the impression that the whizzing of bullets meant no more to him than the buzzing of flies. I don't remember my father being with us in the cellar—I think he might have been at his water mill, which he, along with a few other peasants, had built on the Stuhna before the war. To do this, they dug a canal from the Stuhna towards Tarasivka: this created a small branch on which the water mill stood. Later, in the second half of the 40s, we children used to climb in the tarred compartments of this by-then abandoned and neglected mill.

Uncle Musiy's cellar was relatively large and dry, and many people had gathered in it—our neighbors from the Upper and Lower streets. Uncle Musiy, a lively and restless man of average height (only uncle Anton took after Grandfather Petro—tall and stately), would run out of the cellar from time to time to see “how things were going.” I turned out to be the most restless of everyone in the cellar. The whistle of a shell caused me a painful anticipation of an explosion; the rising sound of this whistle merged with my scream. This was repeated every time. No matter how much they tried to calm me, I could not stop screaming.

During the battle, Germans would jump into the cellar and inspect us. We sat in the cellar for probably about a day. The battle raged at night. Still in the dark, before dawn, the Germans were driven out of the village. Someone announced: “Ours are here.” We left the cellar and entered Uncle Musiy’s house. Soldiers ran into the house and asked for something to eat. Something was found for them, but then several more soldiers, three it seems, asked for the same. There was nothing to give them. My mother suggested they go to our house, where some food was left. So we set off for our house. But just then, from the west, some large flaming balls flew across the sky above us. The soldiers shouted for us to run after them, but we ran in the other direction, towards Uncle Anton’s house. Thus we and the soldiers ran in different directions. And to the west, on the Lower Street, just a few houses away from us, a house was on fire.

From then on, our house became overcrowded with soldiers. At night they lay tightly packed on the sleeping platform and on the earthen floor. When I needed to go out, I could barely squeeze my legs between their bodies. The soldiers lying on the sleeping platform would rock the cradle with Liuba, which hung above them. They joked. I remember an officer pinning a diamond-shaped badge to my shirt, saying: “Istrebitel” (Fighter), and added: “Moloka” (Milk).

Then the wave of Soviet troops rolled on. But during the departure of the last units, an incident occurred with my brother Fedir (who was 10 at the time). A group of “rear echelon troops” trailed at the tail end of “our” army. They discovered that a multi-colored flashlight was missing and suspected that my brother had taken it. Some threats began, the content of which I do not remember. My visual memory has preserved only the very same picture that I had already seen in our neighbor Yivha’s house. This time it was my mother on her knees, pleading. As I recall, those pleas lasted a long time. At least in my memory they remained long and painful. The pleas had no effect: the rear echelon troops decided to take the teenager with them. They dragged him onto a truck, but they allowed my mother to go with him after all. Only somewhere near Kaharlyk were they released.

Men of older and younger ages began to be drafted into the army from the village. The age limits had been expanded. They took my father and my brother Pavlo. We were lucky to meet Pavlo again. He was stationed near anti-aircraft guns in or around Kyiv. He had to stand in cold water and caught a cold in his legs. Consequently, he was allowed to stay home for a few days: he warmed his legs on the stove; this was our last meeting with him until his return from the army.

* * *

Those who were drafted from the villages during the offensive were treated in a special way—after all, they had been in occupied territory (they had not been evacuated or joined the partisans). I am convinced that even if the Soviet troops had not been encircled near Kyiv, and even if people had been helped to evacuate, the majority of peasants would not have agreed to leave their homes. Only a tiny minority, closely connected with the authorities, would have taken advantage of this. Among them, only a few would have done so out of conviction, others—out of fear for their lives. I don't think the reason for this should be seen in the peasant's attachment to his “homestead.” The main reason was the fresh scars of the violence they had endured, especially the recently experienced Holodomor. After an organized famine, only a cynic could call on peasants to be patriots. Even a perpetrator would not have believed the sincerity of someone who said that he did not remember this or had forgiven it.

In any case, those drafted in the newly “liberated” villages faced another act of revenge. They, untrained, often not even dressed in military uniforms, were thrown at machine guns. This is a known fact today. It was said that they were given a drink “for courage” beforehand. Now, it is probably difficult to calculate the number of those deliberately sent to their deaths among those long lists of those “who died a hero’s death,” whose names we read on the columns above the mass graves in the “liberated” villages. However, is it even worth counting, considering the disregard for “our” lives by “our own” in this war.

Indeed, this is a Russian state tradition: ordinary people are just material. If the need arises to sacrifice them for “higher goals,” then such a sacrifice is justified. To think about how necessary the sacrifice is, or to make efforts to reduce the number of victims, means to show a sentimentality unacceptable for a politician, a lack of firmness. Lenin was not the first to introduce this political “ethic”: it was formed along with the formation of the Russian state. One can easily trace the inheritance of such a “political culture” through all periods of the Russian empire. The continuation of this tradition, in an updated form, is the involvement of a significant part of the modern Ukrainian political elite in the plunder of their own people. Without understanding this tradition and renouncing its criminal component (and such a renunciation presupposes the formation of a political elite with a fundamentally different political culture), all of today’s talk about overcoming corruption will remain just talk. Just like the talk about the “fight” against poverty.

So, my father died “a hero’s death,” not far from his native home in the steppes of the Kyiv region—in the village of Kruti Horby. Although my father, as one can judge from the story of a man from a neighboring village (Sloboda), did indeed show courage. When this man was wounded, my father pulled him away from the machine gun (thus saving him) and replaced him at the gun. I remember, I was sitting on the stove when the door opened, and we, the children, heard not sobbing, but the scream of a mortally wounded person—our mother. I also began to cry loudly, probably not yet understanding what had happened. My mother’s words “who did he leave you to” became the accompaniment to our lives. As it did for the lives of many other women and children, regardless of whether it was the Nazis or the Bolsheviks who doomed mothers to struggle single-handedly for the survival of their children.

I returned to thinking about the war again and again. Some new facts or assessments were superimposed on my childhood impressions. It was important to comprehend this war not only in the context of the world war, but primarily in the context of Ukrainian history. It is morally unjustifiable to look at historical events as something completely independent of the people—especially a large nation. If the Ukrainians, like the Poles, had defended their independence in the 1920s, the appearance of another strong, democratic, independent state in Eastern Europe could have changed the course of history. Perhaps the fate of Russia as well. There is a grain of truth in the statement “there can be no democratic Russia without an independent, democratic Ukraine” (to paraphrase Lenin's famous saying). In any case, the attempt to keep non-Russian peoples in one state by force will always be a source of anti-democratic tendencies in Russia. But during the First World War, the West did not understand the importance of establishing an independent, democratic Ukraine: it was then far from a well-thought-out geopolitical strategy for the long term.

Psychologically, the death of my father, whom two totalitarian systems killed with their combined efforts, gave my aversion to totalitarianism a personal motive. Hence the sharp rejection of the rhetoric of praise, which became a traditional ritual associated with the “liberation” and victory (a tradition that is maintained even in independent Ukraine). Not a comprehension of the war and the nature of totalitarianism, but the sound of victorious fanfares. Of course, the people who went through the crucible of war, looking death in the face, deserve respect. But my respect and sympathy for these people were combined with the bitter recognition that, having gone through the war, they were still unable to make sense of their experience (with rare exceptions—Hryhorenko, Rudenko, for example!).

My late cousin, uncle Musiy’s son (also Vasyl), who flew a “kukkurudzianyk” [Po-2 biplane] throughout the war, described my concerns for the fate of Ukraine and its unique culture as “nationalism”—understandably, in the negative sense of the word. And today, unfortunately, a large part of the former participants of the war remain ideological supporters of that “internationalism” which is only a guise hiding the stereotypes of Russian chauvinism. It is difficult to combine in the imagination and mind their experience with this powerlessness in comprehending what they lived through. And I, like other sixtiers, was haunted by a sense of duty to comprehend this experience of standing face to face with death in that war for them. I recall when, in the camp, I was thrown into the “shizo” (punitive isolation cell) once again, Major Fedorov “visited” me for a “talk.” Given his officer rank, I addressed him with a tirade something like this: “How can you, an officer, participate in this torture of political prisoners, obediently carrying out the orders of your superiors? Has it completely faded from your memory how many soldiers and officers recently in the Great Patriotic War stood face to face with death and how many of them died? Where is your officer's honor and courage? I am the son of one of those who died in that war. Do you really think that for the sake of saving my life, or out of fear of a mighty totalitarian state, I should forget my father’s death and flee the battlefield?” Thus I tried to awaken in him a feeling called “honor.” Later, something about this rhetoric of mine bothered me: first, the demagogic use of my status as “son of a hero who died a hero’s death” (and what to say to the sons and daughters of those who died in the ranks of the UPA?), and second, to whom was this tirade of mine addressed (in the camp, the major was considered a “total goner”).

And today, the official commemoration of “victories” has not grown any wiser. The official rhetoric stubbornly clings to cheap populism, sweetened with sentimentality and the pathos of thoughtless romantic heroics. And the desire to fuel the stereotypes of Russian chauvinism with that emphasis on the unity of the “Soviet” peoples as a guarantee of victory. In order to continue to destroy those peoples, their national identity, in the name of unity. Instead of becoming an occasion for reflection on the nature of totalitarianism and Russian chauvinism. And to prevent their return in new modifications—even in softened and hidden forms. Of course, the question arises here, who is interested in people being able to think? Obviously, not someone who would like to have a people that is easier to deceive and rob. And not a Russian chauvinist and imperialist, who considers the disappearance of cultural differences between “fraternal peoples,” the so-called “yedinobrazie” [uniformity], to be the most important guarantee of unity. Ivan Svitlychny's phrase comes to mind here, which can be conveyed almost verbatim: you think that they up there are “thinking,” but they are not thinking. To express my attitude to thoughtless pathos, I resorted to a publicistic style of speech:

Так легко напрошується зваба самовтіхи:

ми довели правоту і силу.

Стій! — відкинемо знову завісу,

щоб залишити правду сину.

Правду, омиту слізьми і кров’ю,

не ховаймось від її сяйва в гроти:

фашизм – це віра в свою ідею

і нищення всіх, хто проти.

…………………………………..

Чом би вам у світлі аналогій

на Отечество не глянуть свіжим зором.

Тож воно крізь галас демагогів

вам кричить насильством і терором.

Нехай істина і совість живить слово,

не патетика бездумна й тупіт ніг,

бо ж тоді той диктатури голос

перемогу вашу переміг.

When people today speak of the romance (or even heroism) of the dissident movement, they do not always take into account the hidden sources from which it grew. For, in addition to purely cultural and intellectual sources, every young man and woman who possessed moral imagination inevitably had to comprehend this standing face-to-face with death of our grandfathers and fathers. It did not matter whether they were martyrs in the torture chambers of the Cheka-GPU-NKVD-MGB, or UPA fighters, or soldiers of the “Great Patriotic” war, or all of these combined. In particular, the resistance movement and the associated philosophy of existentialism are one of the sources of existential motifs in the work of the sixtiers. The generation of people spiritually close to me in the 60s considered it their duty to comprehend the bloody experience and to be honest in their conclusions. Honesty in conclusions meant a strict dependence of one’s own behavior on the meaning that was revealed to us. This is called the existential understanding of truth and value.

Chapter II. The Ruin of Daily Life, Fragments of Tradition

1. The Ruin of Daily Life. The Fate of My Brothers and Sisters

Mother. So, in 1944, three of us children were left with our mother: Liuba, me, and the oldest of us, Fedir, who was 11. Our mother's struggle for our survival began. A few brushstrokes for my mother's portrait. The first is energy, an unwillingness in any situation, even a hopeless one, to retreat, to fall into despair. She stubbornly fought for our lives. But not by any means necessary. She had a natural aversion to making even the slightest gesture of fawning to the village authorities (for example, the brigade leader) in order to get something for us. This was still characteristic of many peasants of the generation to which she belonged. It is surprising how this breed of people could have survived, having endured all the humiliations aimed at eradicating “character”—the sense of independence and dignity of a farmer. I have mentioned here a side of my mother's soul that has remained an unattainable ideal for me. And yet, for me, inclined to take into account the “dialectics of life” (and this expression contains not only positive connotations), this example of her proud independence was important.

Her second profile contrasts with this first one. She had delicate, intelligent facial features, a poetic soul, a distinct aesthetic element in her attitude toward the world. But what charmed me most about her, preserved in spite of everything, was her faith in the good foundation of the world. Not even the circumstances of life, nor her exhausting efforts to ensure our survival, nor twenty years of severe physical suffering (which she affectionately called “my little torment”) killed this faith. Neither life circumstances nor physical suffering managed to break this most important axis of her spirituality. She had, like many rural people of her generation, a faith in the goodness of the first people she met. This is a well-known (and perhaps now forgotten) trait of a rural person, the most vivid manifestation of which was the attempt to strike up conversations with passengers on public transport. To confide in them as if they were good acquaintances. A strange contrast of different worlds. In the structure of traditional rural culture, a person saw in every passerby a conversationalist, an advisor, and a helper. Someone to whom one could complain, find understanding and support. This openness sometimes exposed my mother to bitter disappointments. I would explain to my mother that she had just met a bad person. Of course, one can understand a city dweller who has reasons to be wary of very undesirable acquaintances in a city crowd. But this sentence of mine explains far from everything. Something else, more important, remains beyond it.

Mother, as I can judge from stories, was physically strong, but in 1932 or 1933 she suffered from typhus, which she contracted while caring for her niece Oleksandra (Sasha). I want to note in passing that my mother's younger sister's (Olena's) husband, Rozhovets Ilarion, died of typhus in 1933. He worked at the “Arsenal” factory (Kyiv), and in the autumn of 1933, they were sent to one of the villages in the Kyiv region to gather the harvest; he contracted typhus and died. Famine, typhus, war, the death of her husband, the post-war efforts to save us—all undermined my mother's health. And so in my imagination, I see her thin, sunlit figure, nimble, used to relying on herself, trying, until the last day of her life, to take care of herself, to be neat, so as not to bother others. And a look in which, freed from the captivity of suffering and the shadows of the past, the light of goodness and trust in the world and people radiates.

* * *

After the War. And yet, mother did not manage to save everyone. In the winter of 1944, our Halia fell ill—probably with the flu, which led to complications: from then on, I remembered the word “meningitis.” But it is very likely that Halia’s death was the result of my own action. It happened like this. Mother had placed the children—me and my little sisters—in the bedroom. Between the bedroom and the main room was a large stove that heated the bedroom. The door to the kitchen, where the main cookstove stood, was closed: there was not enough firewood to heat the whole house. One morning, when Halia’s fever had passed and she regained consciousness, I, in my joy, grabbed her and opened the kitchen door to show her to my mother. I stood with her in the open doorway for only a moment: my mother, with a cry of despair, snatched the child from my hands and closed the door. It could be that the deterioration of my sister's condition and her death were the result of my thoughtless act.

The years 1943–1947 were especially hard for my mother, who was left with three small children. The year 1945 brought no change to her situation. Unfortunately, our older brothers, who could have helped, did not return home for several more years. Brother Petro was liberated by the Americans, clothed, fed, and offered a choice: you can return home, or you can stay in the West. Most of the young people chose to return home. Petro did too. But he, like many others, was punished for his stay in Germany. He was sent to the polymetallic mines of Karaganda, where he was forced to work for two years. Pavlo, despite his two years on the front, had to serve, I think, two years in the army.

The main means of salvation was the garden (0.6 hectares of sandy soil) and the cow. Mother made extraordinary efforts to get hay. It was not easy. It had to be bought. She collected milk and made ryazhenka. Once a week, she would go out to the Kyiv road, where so-called “kalymshchyky” (drivers of trucks—mostly “polutorkas” and “ZISs”) made extra money by transporting people to Kyiv. They would seat them on wooden benches in the truck beds, and often on the floor of the bed. The roads then were not paved, let alone asphalted, and no one leveled the potholes. When Fedir enrolled in the FZU (factory-vocational school), I had to carry baskets on a yoke to the road in the predawn darkness (around 3-4 a.m.).