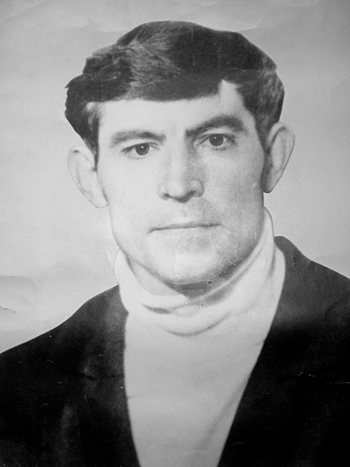

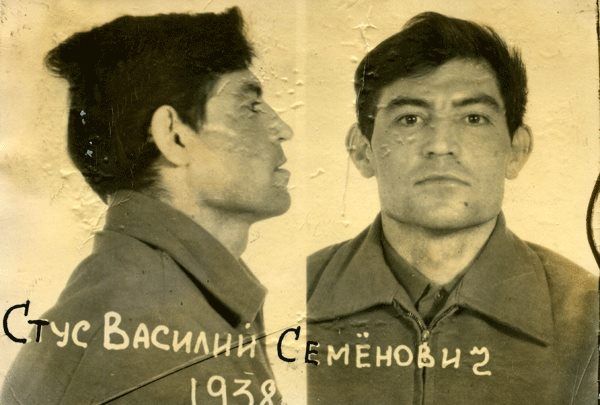

On the night of September 3–4, 1985, the poet and human rights activist Vasyl Stus died in a punishment cell of “Institution VS-389/36” in the village of Kuchino, Chusovskoy District, Perm Oblast.

At that time, I was in cell No. 20 of this “institution,” and I therefore consider it my civic and human duty to bear witness to the circumstances and causes of his death.

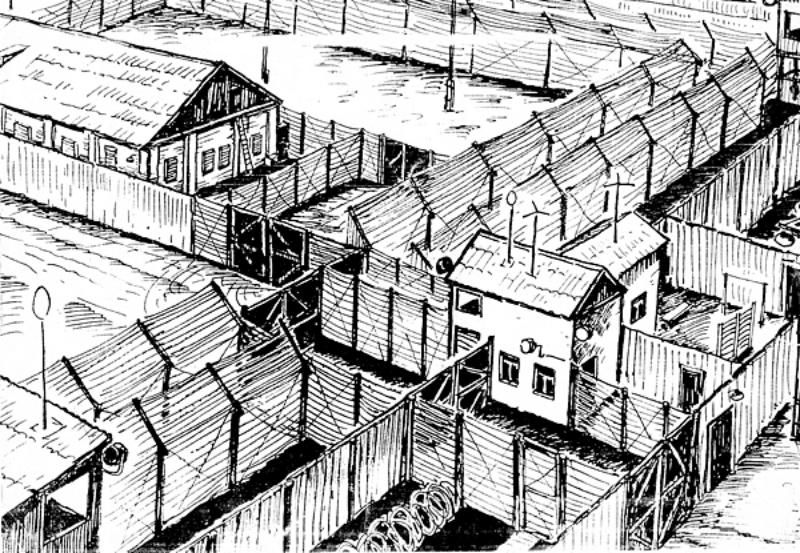

First of all, what is this bashful name—“Institution VS-389/36”?

The Soviet authorities were generally shy about certain terms; for example, they called their opponents not political prisoners but “enemies of the people,” “especially dangerous state criminals,” or “pathetic renegades.” In the prison life of my time, a “citizen convict” was required to address a guard as “citizen controller.”

The history of this last preserve of the Gulag is short. From March 1, 1980, to December 8, 1987, a total of only 56 prisoners passed through it. On average, up to 30 people were held here at any one time. This “institution” soon became known to the world as the “death camp” because eight of its prisoners died, including members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group: Olexa Tykhyi (Jan. 27, 1927–May 5, 1984), Yuriy Lytvyn (Nov. 26, 1934–Sept. 5, 1984), Valeriy Marchenko (Sept. 16, 1947–Oct. 7, 1984), and Vasyl Stus (Jan. 7, 1938–Sept. 4, 1985). Actually, only Stus died directly in Kuchino; the first three died in prison hospitals.

In the early 1970s, there were not so many prisoners in the camps, prisons, psychiatric hospitals, and exile—only a few thousand in total. The political camps were concentrated in the “Dubravlag” administration in Mordovia. However, too much information began to leak from these camps into the “big zone,” as the USSR was then called, and abroad. The KGB therefore decided to destroy its exit channels in a radical way: by moving the most active political prisoners farther away from the center. They chose the Skalninskoye camp administration in Perm Oblast, in the central Urals. There, camps were more common than villages.

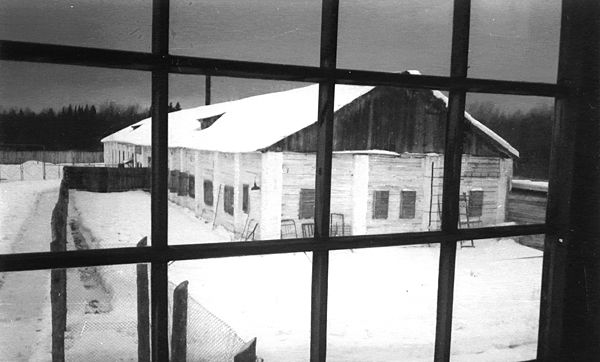

On July 13, 1972, under conditions of top secrecy (even the guards were dressed in tracksuits), the first echelon with several hundred Mordovian strict-regime prisoners arrived at Chusovskaya station. It was in transit for three days. It moved at night. During the day, the prisoners languished in the scorching “Stolypin” cars (that hot summer, forests and peat bogs were burning). They fainted. One prisoner serving a 25-year sentence, Hryhoriy Nykytyuk from Rivne Oblast, died in the car. Many could not stand on their feet when they were unloaded. They were placed in the zones of VS-389/35 (Vsekhsvyatskaya station, Centralny settlement), 36 (Kuchino village), and 37 (Polovynka village), which had been vacated of criminal prisoners.

Another large transport of strict-regime prisoners from Mordovia arrived in the Urals in the summer of 1976.

Finally, shortly before the Moscow Olympics, on March 1, 1980, 32 special-regime prisoners were transferred to Kuchino from Sosnovka in Mordovia. Again, one died en route. Among those transferred were members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group: Levko Lukyanenko, Olexa Tykhyi, Bohdan Rebryk, and Danylo Shumuk. A wooden building of a former sawmill, a few hundred meters from the strict-regime zone, was adapted for the new “special-regime institution VS-389/36-1.”

At various times and in various cells, in addition to those already mentioned, the following UHG members were punished here: Oles Berdnyk, Ivan Kandyba, Vitaliy Kalynychenko, Vasyl Ovsienko, Yuriy Lytvyn, Mykhailo Horyn, Valeriy Marchenko, Ivan Sokulsky, Petro Ruban, and Mykola Horbal, as well as its foreign members, Estonian Mart Niklus and Lithuanian Viktoras Petkus, who joined the UHG in its darkest hour—in 1982. I, too, spent six years of my life here. Nearby, in the strict-regime camp, sat the Head of the Group Mykola Rudenko, Myroslav Marynovych, and Mykola Matusevych. A total of 19 people. Never and nowhere did we gather in such numbers (albeit in different cells), except perhaps at ceremonial meetings for the 20th, 25th, and 30th anniversaries of the Group.

Also punished here were Ukrainians Ivan Hel, Vasyl Kurylo, Semen Skalych (Pokutnyk), Hryhoriy Prykhodko, and Mykola Yevhrafov. Thus, as in every political camp, Ukrainians constituted the majority of its “contingent.” In this true “international,” many years were spent by Lithuanians Balys Gajauskas and Viktoras Petkus, Estonians Enn Tarto and Mart Niklus, Latvian Gunārs Astra, Armenians Azat Arshakyan and Ashot Navasardyan, and Russians Yuri Fyodorov and Leonid Borodin. Most of these people were well-known human rights activists and leaders of national liberation movements, and upon their release, they became politicians and public figures. For the Soviet authorities, however, they were EDRs—“especially dangerous recidivists.” There were also several “especially dangerous criminals” whose death sentences had been commuted to 15 years of imprisonment (accused of collaborating with German occupiers, one of espionage).

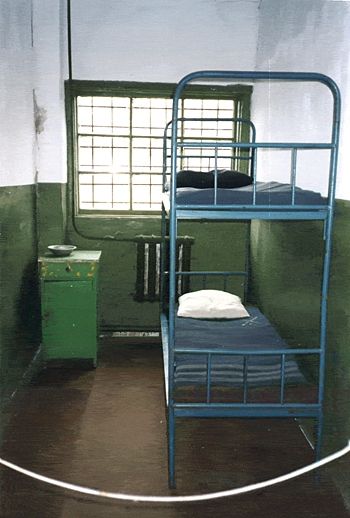

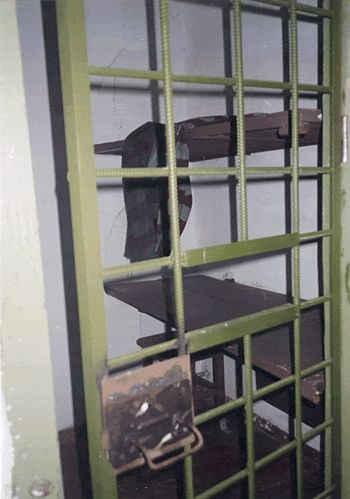

In fact, this was not a camp but a prison with an extremely cruel regime. While in criminal camps recidivists were taken to workshops in the industrial zone, we worked in cells across the corridor. We were given one hour of walking time per day in a courtyard measuring 2 by 3 meters, clad in sheet metal and covered from above with barbed wire, with a guard on a platform. From our cells, we could only see a fence 5 meters from the window and a narrow strip of sky. There were seven types of fences, including electrified wires. The perimeter’s exclusion zone was 21 meters wide. Our food cost 24–25 rubles a month; the water was rusty and smelly. Our heads were shaved like Egyptian slaves, and all our clothes were made of striped fabric. We were allowed one visit a year and one parcel up to 5 kg—also one a year, after serving half the term—and they tried to deprive us of even those. Some of us went for years without seeing anyone but our cellmates and guards. The work involved attaching a small panel, into which a light bulb is screwed, to the cord of an iron. The work wasn't hard, but there was a lot of it: failure to meet the quota, like any violation of the regime, was punished with the punishment cell, deprivation of visits, parcels, and the commissary (where we were allowed to buy an additional 4–6 rubles worth of food each month). “Malicious violators of the regime” were punished with a year of solitary confinement or a transfer to a prison for three years. Under General Gendarme Andropov, in 1983, Article 183-3 was added to the Criminal Code, under which systematic violations of the regime were punishable by an additional five years of imprisonment—this time in a criminal camp. This opened up the prospect of life imprisonment and, especially, a quick reprisal at the hands of criminals.

However, the psychological pressure was the hardest to endure. In Stalin’s time, when entire categories of the population unfit for building communism were exterminated, the authorities no longer cared about a person thrown into the camps to be turned to dust. In our time, the court’s verdict was not final. By our time, it was rare for someone to end up in a political camp “for nothing.” These were active people who, upon release, could rise up again. Therefore, the authorities closely watched everyone, determining the significance of the individual and their potential—and treated them accordingly. It was a kind of expert examination: they studied the trajectory of a person's development (or decline) and took preventive measures to ensure they would not grow into a greater danger to the state. From this point of view, the Ukrainian poet and human rights activist Vasyl Stus indeed posed a particular danger to the Russian empire, which masqueraded under the name of the USSR. Stus, along with other human rights activists, truly did undermine the Russian communist totalitarian regime, which hypocritically called itself Soviet power. And it did fall—having exhausted its economic potential, unable to withstand the military confrontation with the West, and having suffered an ideological collapse. We fought on this front—the ideological one. And we won. In 1991, the Russian empire collapsed.

Having served 5 years of imprisonment in Mordovia and 3 years of exile in Kolyma, Vasyl Stus was arrested for a second time on May 14, 1980, during the “Olympic roundup”: Moscow and Kyiv, where part of the games were to be held, were being cleansed of undesirable elements, including the remaining dissidents who had gathered in the Helsinki Groups. (A joke at the time was that dissidents came in three types: pre-sidents, sidents, and ex-sidents—who then became pre-sidents again.) After his first imprisonment, Stus managed to stay in Kyiv for only 8 months.

Stus repeatedly wrote from exile, starting in October 1977, about his readiness to join the Group, despite his somewhat critical attitude toward it. However, the activists in Kyiv cautiously refrained from putting his name on the Group’s documents. But when Stus returned to Kyiv in August 1979, no one could hold him back: even the 75-year-old Oksana Yakivna Meshko, who had so far survived, looked up at his majestic figure.

“In Kyiv, I learned that people close to the Helsinki Group were being repressed in the most brutal manner. This was how, at the very least, Ovsienko, Horbal, and Lytvyn were tried, and how they later dealt with Chornovil and Rozumnyi. This was not the Kyiv I wanted. Seeing that the Group had been virtually abandoned to its fate, I joined it, because I simply couldn't do otherwise. When my life has been taken—I have no need for crumbs... Psychologically, I understood that the prison gates had already opened for me, that in a few days they would close behind me—and close for a long time. But what was I to do? Ukrainians are not allowed to go abroad, and I had little desire to go—to that foreign land: for who here, in Great Ukraine, would become the throat of outrage and protest? This is fate, and one does not choose one's fate. So one accepts it—whatever it may be. And if one does not accept it, then it chooses us by force...” (“From the Camp Notebook,” entry 6 // V. Stus. Works in 6 vols., 9 books. – Vol. 4. – Lviv: Prosvita, 1994. – p. 493).

“But I was not going to bow my head, no matter what. Behind me stood Ukraine, my oppressed people, for whose honor I must stand until I perish.” (Ibid., entry 4, p. 491).

(It is strange now to hear from some seemingly serious people that Oksana Meshko “dragged” Stus into the UHG and that he died because of her. This, when Stus’s letters from the autumn of 1977 have already been published, in which he insists from his Kolyma exile that his name be put on the Group’s documents, that he is ready to “place his own head under the hefty club.” – Vol. 6, book one. – Lviv: Prosvita, 1997. – p. 295 et al.).

With the standard sentence of 10 years in a special-regime camp, 5 years of exile, and the “honorable” title of “especially dangerous recidivist,” Vasyl Stus arrived in Kuchino in November 1980. Here, he was watched with particular vigilance. Stus had somehow managed to send most of what he had written in the strict-regime camp in Mordovia to the outside world, including some in letters, at times writing poems as continuous prose and replacing words sensitive to the censors (тюрма [prison] – юрма [crowd], колючий дріт [barbed wire] – болючий світ [painful world], Україна [Ukraine] – батьківщина [fatherland]). From the Urals, however, he only managed to send 6 poems in letters to his wife. In the special-regime camp, we were allowed to write one letter a month. You would polish it so carefully—and still they would find “prohibited information,” “code in the text,” or simply declare the letter “suspicious in content.” And confiscate it. Or send the letter to Kyiv for translation, and only then decide whether to send it to the addressee. They would suggest: “Write in Russian—it will arrive faster.” But how can you write to your wife, your own mother or child in a foreign language?

One could receive letters from anyone, but in reality, we were only given some letters from relatives. In the final weeks of his life, Vasyl received a telegram from his wife about the birth of his grandson, Yaroslav. Major Snyadovsky summoned Stus to his office, congratulated him, and read part of the telegram, but did not hand it over: prohibited information. This greatly outraged Stus.

Searches. They were conducted two or three times a month, but there were periods when a prisoner could be searched several times a day—just for harassment. One could keep 5 books, brochures, and magazines, combined, in the cell. The rest—out to the storage room. But everyone subscribes to magazines and newspapers, tries to work on something, even just learning a foreign language. That already requires a dictionary and a textbook. But the regime is relentless: excess books are thrown into the corridor.

We would take slips of paper with foreign words to work to study them (Stus was fluent in German and English and was learning French). They would be taken away. When taking you to work, they would lead you to their “guardhouse”—and you'd have to strip naked. They would feel every seam, look into every fold of your body. I can still hear Vasyl’s pained voice: “They paw you like a chicken...” Such a remark was enough to land you in the punishment cell.

They were especially vigilant as a visit approached. If the KGB decided not to grant you a visit, depriving you of it was a technical matter: the guards are tasked with finding a violation of the regime. He spoke through the small window with the neighboring cell. He failed to meet the production quota. He declared an illegal hunger strike. The head of the regime, Major Fyodorov, personally discovered dust on a hanger. The same Fyodorov once punished Balys Gajauskas for “not being candid in conversation.” And had he been candid and said what he thought of him—he would have been an even bigger violator of the regime. Stus had only one visit in Kuchino. When they were taking him to the second one, he could not endure the humiliating search procedure and returned to his cell.

They began to “press” Stus particularly hard starting in 1983. On his birthday, which is Christmas, they conducted a shakedown. They took his manuscripts. Stus calls for the officer on duty, Major Galedin, demanding they either return the manuscripts or draw up a report of their confiscation.

– And who took them?

– That new major, I don’t know his name. That Tatar.

A report was filed that Stus had insulted the national dignity of Major Gatin. Although he was indeed a pronounced Tatar, he had likely already registered himself as a member of the higher race—the “great Russian people.” Stus is thrown into the punishment cell. At the same time, they threw the Estonian Mart Niklus into a punishment cell:

– Vasyl, where are you?

– In some gas chamber named after Lenin-Stalin! And Gatin-the-Tatar!

A loudspeaker is turned on in the corridor.

Later, at work, energetically tightening screws with a mechanical screwdriver, Vasyl improvises: “For Lenin, for Stalin! For Gatin-the-Tatar! For Yuri Andropov! For Vanka Davyklopov! And just a tiny bit for Kostya, for Chernenko. How can you even fit him into a rhyme?”

One time I accidentally overheard Stus talking to KGB officer Vladimir Ivanovich Chentsov:

– You say you’ve put my manuscripts in a warehouse outside the zone. But I know what you want—for nothing of me to remain after I die… I no longer write my own things, I only translate. So give me a chance to finish something at least…

It was easier for those who could stop writing in captivity. An artist, my cellmate Yuriy Lytvyn used to say, is like a woman: if he has a creative idea, he must give birth to a work. And just as it is unbearable for a mother to see her newborn child being destroyed, so it is for an artist when his work is destroyed. Even more so when that child is torn from the womb prematurely and trampled by the dirty boots of the guards…

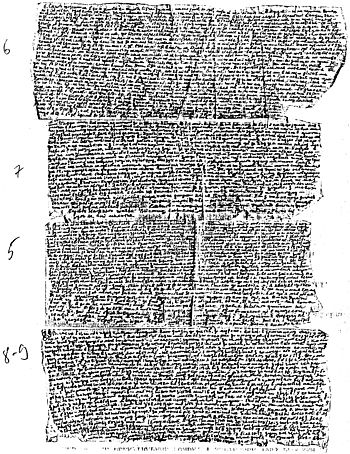

In February 1983, Stus was locked up in solitary confinement for a year. When he came out, we were put together in cell No. 18 for about a month and a half. I read his handmade thick notebook in a blue cover (without a title) with several dozen poems written in free verse, and a graph-paper notebook with translations of 11 of Rilke's elegies. I was in a poor physical state at the time (my heart was aching) and did not manage to memorize a single poem. And I didn't expect us to be separated so quickly. In letters from Sept. 12, 1983, and December 1983, Stus calls this collection “Bird of the Soul” and writes that it contains about 40 poems (Vol. 6, book 1, pp. 444 and 449), while in a letter from Feb. 1, 1985, he writes of 100 poems. “And 50 more are maturing in drafts” (p. 483). And he also writes: “...a collection burns in my soul called ‘Passion for the Fatherland’” (p. 479, letter from November-December 1984). “I translated Rilke’s ‘Elegies’—that's about 900 lines of poetically extremely difficult text” (p. 444, letter from Sept. 12, 1983).

That “Bird of the Soul” never flew out from behind bars. And let us not console ourselves with the sweet fairytale that manuscripts don’t burn. Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska says: “…the tree of Stus's poetry—its crown is chopped off near the top…” (Vol. 1, p. 28). This is yet another crime of Russian imperialism against Ukrainian culture. From his five years in Kuchino, what remains are 45 letters, 6 poems, and a text titled in published editions as “From the Camp Notebook.”

…In October 2000, I once again traveled to Kuchino for an academic conference on totalitarianism. I also went as a living exhibit of the Perm-36 Memorial Museum of the History of Political Repression and Totalitarianism, which operated from 1995 to 2014 in our painfully familiar concentration camp and the neighboring strict-regime camp. And there I met my former cellmate, the Lithuanian Balys Gajauskas, and his wife, Irena Gajauskienė.

I showed Balys and Irena a photocopy of Vasyl Stus's manuscript “From the Camp Notebook.” Mrs. Irena said:

– It was I who brought this out…

Balys added:

– It was easier in Mordovia. Many people brought information out from there. But they also moved us from Mordovia because there were channels there. In 1980, when we were being moved from Mordovia to the Urals, someone asked the camp chief Nekrasov where they were taking us. He replied: “You are being taken to a place where you will not write.”

So, Stus wrote even there, where writing itself was already a crime. Especially things like “From the Camp Notebook.” These 16 scraps of capacitor paper take up 12 pages in a book, but their explosive power was so great that it struck Vasyl himself. I believe that one of the reasons for his elimination was the appearance of this text in the West.

The second reason was the effort to nominate his work for the Nobel Prize. Vasyl Stus's poems had already been published in foreign languages. The world saw the level of the Ukrainian poet's talent not through the prism of dissidence, but as an outstanding artistic phenomenon.

In my publications from the 1990s, it is said that Stus’s work was supposedly nominated for the Nobel Prize by Heinrich Böll, the 1972 Nobel laureate and President of the International PEN Club (1971–1976; he died on July 16, 1985). H. Böll truly knew the value of Vasyl Stus's work, as his poems were also published in German. He spoke out in defense of Stus on at least two occasions. On December 24, 1984, he, along with German writers Siegfried Lenz and Hans Werner Richter, sent a telegram to the then General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, Konstantin Chernenko, about Stus's alarming state of health. There was no reply. On January 10, 1985, H. Böll gave an interview about V. Stus to a German radio station. It was reprinted in the press. But no document regarding a Nobel Prize nomination exists; no mention of it has been found anywhere.

The historian and journalist Vakhtang Kipiani, in his publication “Stus and Nobel. Demystifying the Myth” (dated July 22, 2006), also in Moloda Natsiya (almanac, No. 1 /38/, 2006. – pp. 355–369), writes: “In the newspaper ‘Ameryka’ dated December 17, 1985 (note—this is three months after Stus's death), we find information that at the end of '84 in Toronto, an ‘International Committee for the Conferment of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Vasyl Stus in 1986’ was established.”

The Committee included prominent scholars and figures of the Ukrainian diaspora, and respected individuals from many countries around the world. The chairman of the committee was Dr. Yaroslav Rudnyckyj. The committee distributed over a hundred letters with requests to send letters of recommendation to the Nobel Committee and organized translations of Stus’s works. But it was planning for 1986.

The Kremlin gang already had enough trouble with Nobel laureates Alexander Solzhenitsyn, whom they had to expel abroad, and Andrei Sakharov, whom they deported to Gorky at the beginning of the Afghan War and held under house arrest. The Kremlin knew that the Nobel Prize, according to its statutes, is awarded only to the living; it is not awarded posthumously. The Kremlin could not allow a Nobel laureate, and a Ukrainian one at that (which would have elevated the “Ukrainian cause” to an unprecedented height), to emerge from behind bars. In 1936, Adolf Hitler found himself in a similar situation. At that time, the Nobel Prize was awarded to the German publicist Carl von Ossietzky. But he was in a concentration camp. Hitler ordered his release. But while the bureaucratic machine churned, the laureate died in captivity.

Moscow dealt with the Ukrainian candidate for the Nobel Prize according to Stalin's maxim: “No person, no problem.” And this happened during Gorbachev's time. Gorbachev’s defenders will say that he most likely never even heard of Stus. But I am certain that our cases were considered and decided at the highest level. At that time, there were about as many especially dangerous political recidivists as there were members of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee in the Kremlin. You see, Gorbachev initiated “perestroika” without releasing his seemingly natural first allies—the political prisoners—from captivity, as is the custom everywhere. Moreover, he kept us imprisoned even in 1988, and some even in 1989, while he himself, having become a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, began a new round-up of political prisoners. You see, he pardoned us. Meaning he considered us criminals to whom he showed mercy. Our rehabilitation came only in 1991…

I am certain that the administration of camp VS-389/36 received an order from the Kremlin to eliminate Vasyl Stus by any means necessary before the Nobel Prize could be awarded to him.

How did it happen? In prison, you see little, but you can determine what is happening by the sounds.

Vasyl Stus was out of the punishment cell for only short periods. In the summer of 1985, he was in cell No. 12 with Leonid Borodin (a Russian writer, later chief editor of the journal “Moskva,” died Nov. 24, 2011). The cell was tiny; you could stretch out your arms and touch the walls. A double bunk, two stools, one nightstand for both, and a slop bucket. One was allowed on the bunks for only 8 hours a day. Sitting on them at any other time was a violation of the regime.

One night, a soldier in the watchtower was singing loudly. Borodin got up, pressed the call button, summoned the guard, and asked him to call the soldier and tell him not to disturb their sleep. The next day, it turned out that it was Stus who had awakened the whole prison—and he was thrown into the punishment cell for 15 days. Borodin went to argue with the camp chief, Major Zhuravkov, but he said he trusted his subordinates. He already had another task: to destroy Stus.

A few days after the punishment cell, specifically on August 27, 1985, another affliction. Stus took a book, placed it on his top bunk, and read it while leaning his elbow on the bunk. Warrant Officer Rudenko looked through the peephole: “Stus, you are violating the bed-making regulations!” Stus assumed another, permitted, posture. But the duty officer, Senior Lieutenant Saburov, Guard Rudenko, and another guard filed a report stating that Stus was lying on his bunk in his outer clothes during work hours and had argued with the citizen controller when reprimanded. Fifteen days in the punishment cell. As he left the cell, Stus told Borodin that he was declaring a hunger strike. “What kind?” “To the end.”

Previously, Stus had once been on a hunger strike for 18 days. He told me afterwards: “It's so disgusting to come out of a hunger strike having achieved nothing. I will never do that again.”

He was a man of his word.

The punishment cells are located in the northern part of the barracks, in a small transverse corridor. Stus was held in the 3rd cell, at the corner, the one closest to the guard post. No sounds reached us from there. On September 2, we could hear from our work cells that Stus was being led down the corridor to some official. Returning from there, he deliberately said loudly in the corridor: “I’ll punish you, I’ll punish you... Go ahead and destroy me, you Gestapo!” This was how he informed us that he was being threatened with new punishment.

The Estonian Enn Tarto would collect the finished products (cords for irons) from the work cells in the evening and distribute the next day's work. On September 3, around 5 p.m., he heard Stus ask for Validol. The guard replied that the doctor was not available. Then Enn Tarto himself told the doctor, Pchelnikov, who gave Stus the Validol. This means he was having heart trouble.

At the opposite end of that corridor, across from the punishment cells, Levko Lukyanenko worked during the day in work cell No. 7. When he couldn’t hear the guard, Levko would call out: “Vasyl, hello!” Or: “Achy!” Vasyl would respond. But on September 4, he did not respond. Instead, around 10–11 a.m., Levko heard the authorities enter the corridor through a side entrance. He recognized the voices of the camp chief, Major Zhuravkov; the head of the regime, Major Fyodorov; and KGB officers Afanasov and Vasylenkov. They were opening the punishment cell door, murmuring something quietly. And then—an unusual silence. “Even that heathen woman wasn't laughing,” Levko recalled. This was the work supervisor.

That day, a food ration was ordered from the kitchen, as if someone were being transported. In Kuchino, they never gave out a travel ration: the trip to Perm or the hospital took only a few hours; we received it in Perm. But they forgot about that ration.

There was also an incident where Borodin was told to hand over Stus’s spoon. This was an attempt to plant the idea that he had ended his hunger strike.

Over the next few days, we signed up to see the officials for various reasons. Doctor Pchelnikov was not available. KGB officer Vasylenkov was not available. Major Zhuravkov was not available. Major Dolmatov, the political officer, was acting chief. To questions about Stus, he would answer: “We are not obligated to answer you about other prisoners. It is not your business. He is not here.”

There was still a glimmer of hope that Stus had been taken to the hospital at Vsekhsvyatskaya station. But at the end of September, I myself was taken there. I was kept alone, but I still found out that Stus had not been there. Maybe he was taken somewhere further? On October 5, two KGB agents summon me—some local one (sounded like Zuyev or Zubov) and Vasyl Ivanovych Ilkiv, who had come from Kyiv. In our conversation, I name the deceased prisoners of Kuchino: Andriy Turyk, Mykhailo Kurka, Olexa Tykhyi, Ivan Mamchych, Yuriy Lytvyn, Valeriy Marchenko, Akper Kerimov, Ishkhan Mkrtchyan, Vasyl Stus…

– Well, Stus… His heart couldn’t take it. It can happen to anyone.

And at that moment, my heart sank… He had confirmed my doubt.

Так, ми відходимо, як тіні, і мов колосся з-під коси,

в однім єднаєм голосінні свої самотні голоси.

Не розвиднялося й не дніло, а тільки в пору половінь

завирувало, задудніло, як грім волання і велінь.

Та вилягаючи в покосах під ясним небом горілиць,

ми будимо многоголосся барвистих світових зірниць.

Народжень дибиться громаддя, громаддя вікових страстей,

а Бог не одведе очей від українського свічаддя.

То не одне уже світання, тисячоліття не одне,

як ув оазі безталання нас душить, підминає, гне…

Як тавра нам віки, як рана, прости ж, мій Боженьку, прости,

коли завзяття безталанне не винести, не донести.

Та віщуни знакують долю – ще розчахнеться суходіл,

і хоч у прірву, хоч на волю – об обрій кулаки оббий.

Ти ще побачиш Україну в тяжкій короні багряній.

На тихі води і на ясні зорі

паде лебідка білими грудьми.

Вдар, блискавко, і, громе, прогрими,

аби вже не простерти крил – у горі.

Зелені села, білі городи, і синь-ріка, і голуба долина,

і золота, як мрія, Україна кудись пішла, лишаючи сліди.

Отут спинюся на самотині – там, де копита ко́ня вороного

розбризкують геть ярі іскри יдного днів.

…Враз ослонилася дорога, що при самій урвалася меті.

It is entirely possible that death resulted from a heart attack. Let's consider that Stus was on a hunger strike in a cold punishment cell, wearing only pants, a jacket, underwear, a T-shirt, socks, and slippers. Bedding is not provided. You only have slippers to put under your head. The temperature during the day then hardly reached 15 degrees Celsius. The sun does not shine into that punishment cell. In the morning in our 20th cell, Balys Gajauskas and I would see ice on the windowpanes. And Stus had nothing to cover himself with. And no energy to get warm… Lukyanenko experienced similar situations and described them in his essay “Vasyl Stus: The Final Days” (Не дам загинуть Україні! Kyiv: Sofia Publishing House, 1994. – pp. 327–343). It is a psychologically authentic essay.

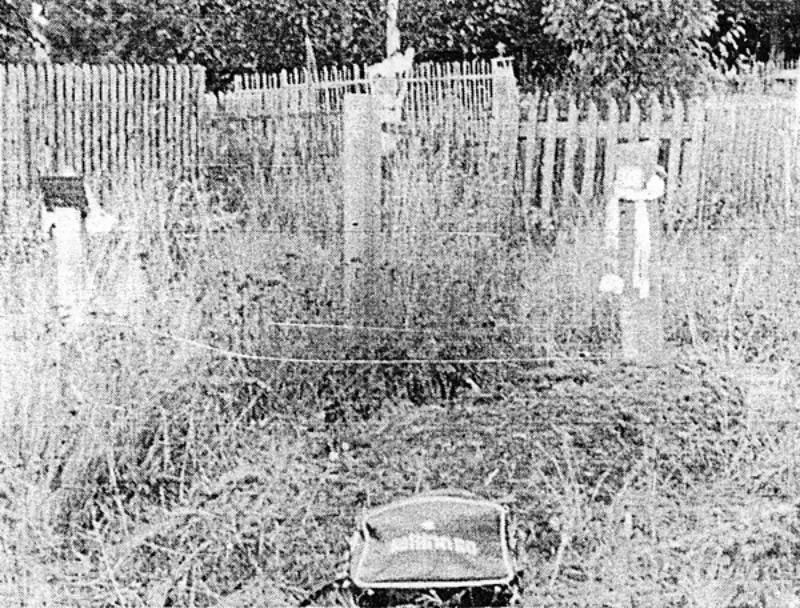

The camp administration had to inform his widow, Valentyna Popelyukh, of her husband's death. Valentyna ordered a zinc coffin and set off on the road with her sister, Oleksandra Loveyko, and friend, Rita Dovhan. At Boryspil Airport, KGB agents categorically advised them not to take the coffin, as the body would not be released to them. (It should be known that the most humane Soviet law in the world did not permit the removal or reburial of a deceased prisoner's body until his term of imprisonment had expired. So the dead remained under arrest.) In Moscow, their son Dmytro, who was serving in the army at the time, joined his mother. They arrived in Kuchino on September 7, and Major Dolmatov told them: “Well then, let’s go to the cemetery.” And he brought them to a freshly covered grave in the village of Borysovo, about three kilometers from the zone.

…On February 24, 1989, the 46-year-old Major Dolmatov was laid to rest next to Stus, just a few meters away. And Major Zhuravkov died about 10 days after Stus. Zhuravkov Jr., a lieutenant and operative, drowned in the Chusovaya River in the summer of 1987. All of this raises serious doubts as to whether Stus's death was truly the result of a heart attack.

Somewhere there in one of the punishment cells (Balys Gajauskas says it was in the 6th), sat Boris Romashov, a native of Gorky. He was a murderer who had “taken a political stance.” He was imprisoned once again for primitive anti-Soviet slogans with which he had defaced his passport and military ID and thrown them into the yard of the military enlistment office. Although he claimed to have a certificate of psychopathy, he was still given 9 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile. He had a conflict with Stus: he had threatened him in the work cell with a mechanical screwdriver. Stus took a defensive posture—and the man did not dare to attack. Both were put in the punishment cells for 5 days for a “mutual brawl.” A year before his release, Romashov tried to kill Balys Gajauskas by striking him several times on the head and in the chest with a mechanical screwdriver. Balys fell under the table, so the blade struck at an angle, missing his heart. For this act, Romashov was punished only with the punishment cell, but a KGB agent would bring him tea there.

At our meeting in Kuchino in October 2000, Gajauskas suggested that Romashov could have been sent to kill Stus…

But in October 1985, Enn Tarto said that Romashov had supposedly heard Stus moan on the evening of September 3, during “lights out”: “They killed me, the bastards...” A few months later, I had the opportunity to ask Romashov if he confirmed hearing Vasyl's moan. – “I don’t want to talk about it.”

It could have happened like this. During “lights out,” the guard tells the person in the punishment cell: “Hold the bunk.” Because they are held up by a pin. The guard, from the corridor, pulls out the pin through a hole in the wall—and the bunk falls down; the prisoner has to lower it gently. A stool is chained to the floor under the bunk, the only place one could sit. The guard could have suddenly pulled out the pin—and the bunk would have struck Stus on the head…

In hindsight, we, the prisoners, recalled and compared all the details. We remembered that on the night of September 4–5, the boarish roar of Guard Novitsky echoed in the corridor: “Give me the knife!” This was them already launching the version that Stus had hanged himself in the work cell with a cord. This version was fed to me in 1996 in Kuchino by a former guard, Ivan Kukushkin. But Kukushkin was no longer working with us at the time of Stus's death. In a conversation with Kukushkin in 2001, Lukyanenko refuted that version. He had carefully noted that no one worked the second shift in his 7th work cell, where Stus was supposedly taken to work. He paid attention to how he left parts on the table. Nothing had been disturbed.

One evening, perhaps September 2, I heard Stus ask for his boots for the work cell. This means he was working the second shift in the 8th cell, which is in the main corridor. From the 7th cell, which is around the corner, I would not have heard his voice.

They tried to spread the version of suicide in punishment cell No. 3 with a sharpened awl through the criminal Vyacheslav Ostrohlyad. But neither a cord nor an awl could have possibly gotten into the punishment cell: Stus was searched very thoroughly.

During the exhumation on November 17, 1989, we did not notice any disfigurement of his face, as is common with hanging victims. Only the nasal cartilage (the tip of the nose) had collapsed. The organizer of the reburial, Volodymyr Shovkoshytnyi, writes: “While the cameramen were filming the body, I drew Chernilievskyi’s [Stanislav, director of the film ‘A Black Candle for a Bright Road’ – V. O.] attention to the fact that above Stus's temple there was a clearly visible skin lesion, very similar to one that could have been left by the bunk if it were suddenly dropped (the guard had such an opportunity).” – See: Vasyl STUS: Poet and Citizen. A Book of Memoirs and Reflections / Compiled by V. Ovsienko. – Kyiv: Klio Publishing House LLC, – 2013. – p. 640.

But, in fact, this exhumation procedure took place under such physical and psychological strain that we were in no state to conduct a proper examination. And we had no expert.

I do not favor either of the two versions. The perpetrators know the mystery of Vasyl Stus’s death. Some of them died soon after, and not by chance. The ones who ordered it know, and some of them are still alive. But they will not confess to the crime.

Of one thing I am certain—it was an order from the Kremlin: do not allow a Ukrainian to become a Nobel Prize laureate. And especially not in a prison cell.

…At the beginning of this article, I mentioned that from 1995, the Museum of the History of Political Repression and Totalitarianism in the USSR, “Perm-36,” operated in our native zone VS-389/36. I considered it the conscience of Russia. Because it is one thing to create a museum to the glory of one’s Fatherland, and quite another to create a museum to its shame, in order to cleanse Russia of the communist filth. Such people appeared at the right time and in the right place. They did a great thing. The museum under the direction of Viktor Shmyrov became on par with related museums like Buchenwald, Auschwitz, and Sachsenhausen. Tens of thousands of people passed through “Perm-36.” But in 2014, under pressure from former KGB agents and guards, the museum was closed. Now its antipode operates there: the “Museum of Camp History and GULAG Workers.” That is, the museum of political prisoners became a museum of our executioners. The main argument: “The Russian state should not maintain a museum to launder the reputations of former Banderites and other fascists.” People like Stus.

Readers know this poem as “The Laments of N. G. Chernyshevsky” with the first line “O my people, when will you be forgiven...” and the fifth “O State of half-sun, of half-darkness...” But at the beginning of 1984, Vasyl wrote it down for me like this:

О вороже, коли тобі проститься

Гик передсмертний і тяжка сльоза

розстріляних, замучених, забитих

по соловках, сибірах, магаданах?

Державо тьми і тьми, і тьми, і тьми!

Ти крутишся у гадину, відколи

тобою неспокутний трусить гріх

і докори сумління дух потворять.

Казися над проваллям, балансуй,

усі стежки до себе захаращуй,

а добре знаєш – грішник усесвітній

світ за очі од себе не втече.

Це божевілля пориву, ця рвань

всеперелетів – з пекла і до раю,

це надвисання в смерть, оця жага

розтлінного весь білий світ розтлити

і все товкти, товкти зболілу жертву,

щоб вирвати прощення за свої

жахливі окрутенства – то занадто

позначене по душах і хребтах.

Тота сльоза тебе іспопелить

і лютий зойк завруниться стожало

ланами й луками. І ти збагнеш

обнавіснілу всенищівність роду.

Володарю своєї смерти, доля –

всепам’ятка, всечула, всевидюща –

нічого не забуде, не простить.

This prophetic verdict of Stus on the Russian Empire is being fulfilled in our time.