Among the global community, the 1956 Soviet military invasion of Hungary provoked a wide wave of protests. Photographs of tanks on the streets of Budapest appeared in almost all the major publications of the time, and dozens of international organizations condemned the act of aggression—the Hungarian Revolution, without exaggeration, shook the entire world. Even sports could not escape the political confrontation: a month after the revolutionary events in Sándor Petőfi’s homeland, a bloody brawl broke out between the USSR and Hungarian water polo teams in Melbourne, and the Olympic match was stopped.

Ukrainians did not stand aside from the events in the neighboring state. The diaspora press was filled with texts on Hungarian topics, one of the most significant of which was Dmytro Dontsov’s article “The Revolution in Hungary,” published on November 25 in the newspaper “Shliakh peremohy,” which called for assistance to the Hungarian insurgents.

Anti-Soviet sentiments began to spread with renewed force throughout the territory of the Ukrainian SSR. According to Danylo Shumuk, “in Volhynia, collective farmers, especially women, were so hostile to the leadership that brigade leaders and chairmen were afraid to approach them. The collective farmers warned the authorities: ‘You’ll see, soon what happened in Hungary will happen in Ukraine.’”

The head of the Drohobych KGB branch, Hrytsenko, reported to Kyiv: “If in 9 months 60 anti-Soviet statements were recorded, then in October-November alone, 97 were recorded. If in 9 months there were almost no open anti-Soviet speeches, in October and November there were 11.”

A similar dynamic is confirmed by the number of political arrests. If 24 people were arrested in 9 months, then in 2 months (October-November), 66 were. According to Yuriy Kyrychuk, unknown persons in the Carpathians even disabled several railway bridges used to transport Soviet troops to Hungary.

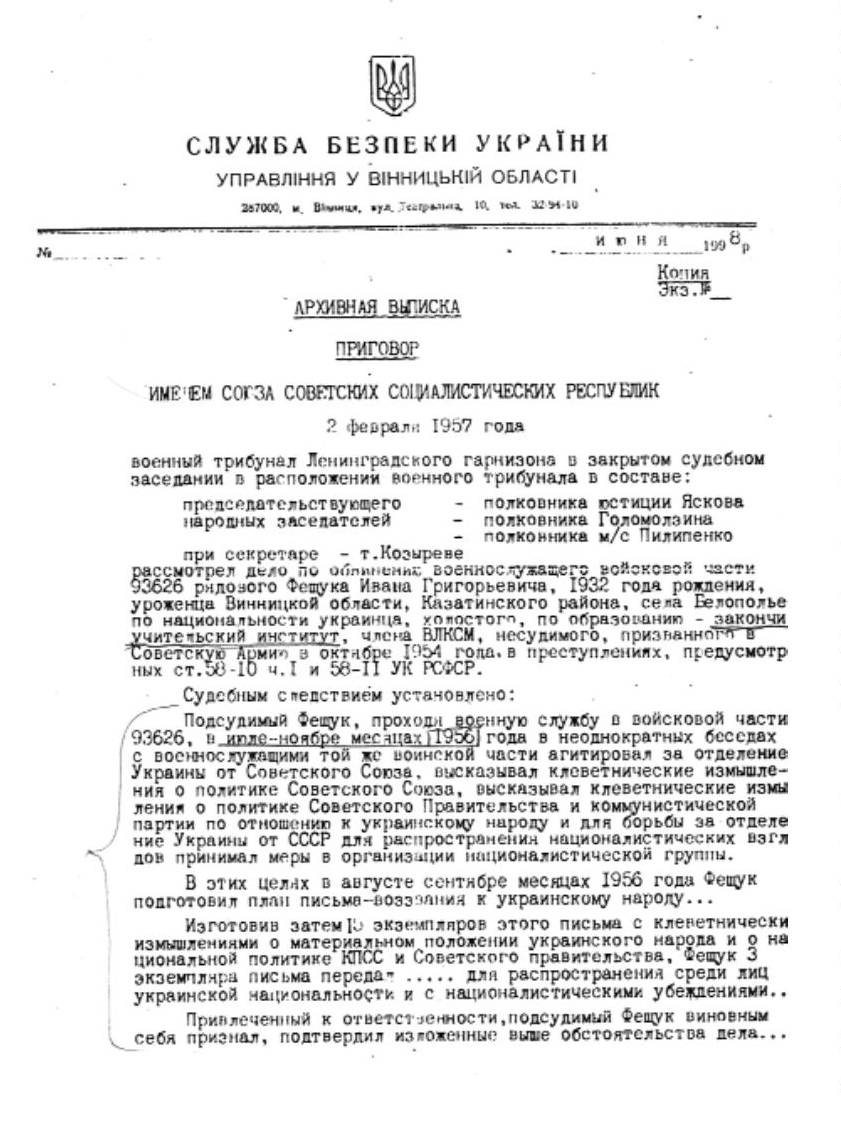

A separate chapter in the history of Ukrainian participation in the 1956 Hungarian events is the story of one Ukrainian—Ivan Hryhorovych Feshchuk.

“...I propose the following addition to Article 31 of the USSR Constitution in my own wording: ‘The Soviet Army has earned with its blood the noble reputation of the savior of the world from fascism, and no one has the right to push it to be used in punitive actions against either the Soviet people or other peoples. State officials who issue such unconstitutional orders must be brought to trial.’”

These lines from the speech of People’s Deputy of the USSR Yevgeny Yevtushenko were delivered from the rostrum of the Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR in Moscow in 1989. Twenty-three years earlier, Ivan Hryhorovych Feshchuk, during his compulsory military service in the Soviet Army, protested against that same “use in punitive actions” and paid for it with a camp term.

After graduating from the Berdychiv Pedagogical Institute, Ivan Hryhorovych worked as a teacher in the village of Perha, Zhytomyr Oblast. From there, he was drafted into the Soviet Army. He served in the airborne troops and was the Komsomol organizer of his company. As fate would have it, three men named Ivan, all graduates of the Berdychiv Pedagogical Institute—Feshchuk, Botsian, and Kasianchuk—ended up serving in unit No. 92626. In fact, almost the entire personnel consisted of Ukrainians whose homelands were the Zhytomyr, Vinnytsia, Rivne, and Zaporizhzhia oblasts.

In 1956, it became clear that their unit was being prepared for an airborne drop. Where exactly was probably no great secret to anyone in the country at the time. Ivan Hryhorovych himself describes the unfolding events: “Our airborne division was stationed in the city of Ostrov (Pskov Oblast). All personnel were urgently re-dressed in new field uniforms. The shoulder boards were sewn on, and sleeve insignia were removed. Leave and vacations were canceled. Exiting the permanent location was forbidden. The checkpoints were doubled. The personnel’s parachutes were re-checked and sealed. All correspondence from the soldiers was stopped.”

To Ivan Hryhorovych’s great surprise, none of the soldiers even considered what awaited them: “The mood among the soldiers was high. I tried to convince the soldiers of the 4th rifle company, where I was the Komsomol organizer, that the role of a gendarme was unbecoming of a guardsman-paratrooper. We are defenders of the Fatherland, as we declared in our oath, and the functions of punishers are not for us.”

However, the worldview of the personnel had been reliably zombified by the command’s ideological propaganda. The command, by the way, besides preserving the agitated Warsaw Pact Organization after the uprisings in Berlin, Poznań, and now Budapest, was probably not averse to receiving its share of awards. The situation was somewhat reminiscent of the mood on the Iberian Peninsula at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th centuries. Spanish grandees at first liberated their homeland from invaders in a patriotic fervor, but when the Reconquista was over, a generation raised on the exploits of its heroes sought similar glories and rewards. Military honors attracted many, and they eventually received them, though no longer by reconquering their own lands, but by seizing foreign ones—on the American continent.

Many, during drills for techniques like bayonet throwing, would say that they would show how it’s done, but in Budapest. “And what if they tell us to go to Western Ukraine? Are we to shoot our own brothers and sisters?”—such conversations were held not only by Ivan Hryhorovych but also by Botsian and Kasianchuk. The three of them combined their efforts, rightly deciding that alone their already slim chances of success would be practically nil.

There was no specific plan of action; indeed, there could not have been one. A fearless assessment of the government’s actions—essentially a critique—within a military unit that was supposed to implement the very decrees of that government made even the illusion of thorough work impossible. Therefore, their activity took the form of simple conversations with personnel, discussions within the group itself, and the production and distribution of leaflets.

Ivan Hryhorovych himself distributed 15 leaflets, which, along with the aforementioned conversation overheard by a captain from the regimental staff, drew attention to him. “That captain knew me well. He summoned me to the headquarters and asked me to rewrite one of the protocols. It later turned out: for handwriting analysis. The leaflets written in my hand were already in the Special Department of the military unit.”

However, the work continued for another day or two: “Soon, our entire organization of Ukrainians was assigned to the daily guard duty, and we were given all our personal documents (which never happened, especially considering the preparation for the drop) and two ammunition loads instead of one. It was a clear provocation, but at the same time, we understood there was a traitor among us... However, within 2-3 days, an ‘all-clear’ was announced throughout the division, and the combat readiness mode was lifted.” Thus, thanks to the three brave men, only one regiment from that division was sent to Hungary, and even that one was stationed far away in the Baltics, in the city of Valga, at the time.

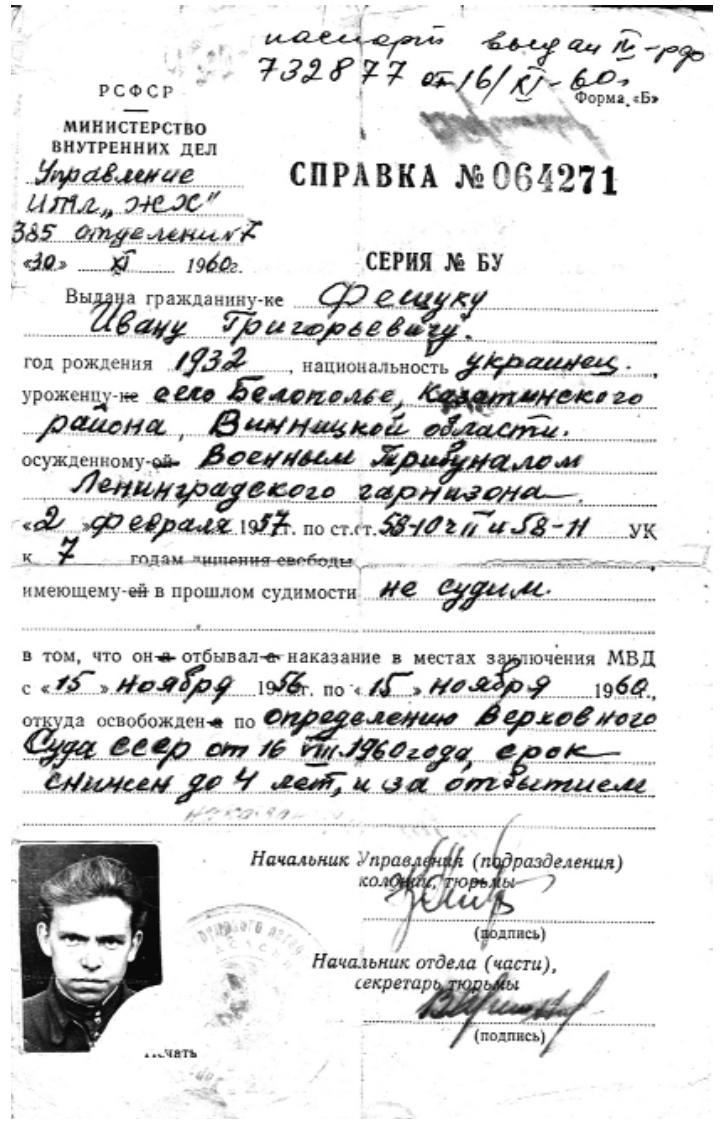

On November 15, 1956, private of military unit 93626 Ivan Feshchuk was arrested. He was charged under Article 58 of the RSFSR Criminal Code—“treason against the Fatherland.” The penalty was death by firing squad. The investigator insisted on “anti-Soviet agitation.” Ivan Hryhorovych admitted his “guilt.” It seemed the “incident” was resolved, but the Soviet justice system did not dare to engage in outright legal blasphemy.

Firstly, the words “Hungary,” “Vengriya,” or even the loan-translation “Madyarshchyna” did not appear in the leaflets, nor were they used in oral agitation. The organization opposed any unlawful aggression (if aggression can ever be lawful) and denied its expression in military invasion and the violation of another state’s sovereignty. As we can see, this depersonalization also served a conspiratorial role.

Secondly, the USSR had not formally declared war on Imre Nagy’s country. Even all the radios claimed that the socialist bloc countries were only providing international assistance to Hungary. Therefore, legally, there could be no state of war, either in the city of Ostrov or at any other point in the country. Consequently, the term “treason” could not be applied in the context of interpreting an illegal act in the armed forces during combat operations.

The lack of evidence, the silence of the soldiers (they either remained silent or denied the fact of agitation), the fruitless searches, and the inconclusive confrontations (as even the organization’s provocateur refused to speak at them) forced the prosecution to reclassify the capital charge. Soviet jurisprudence replaced it with Articles 58.10 and 58.11 (“bourgeois nationalism”), with a sentence of 7 years’ imprisonment.

Ivan Hryhorovych was first held in the Pskov prison, then in the internal prison of the city of Leningrad. The political prisoner recalls his time there: “I found out that Lenin had once been held in the cell next to mine, No. 193. At first, I tried to find out by tapping on the walls if anyone was there, but no one responded to my signals. Then I decided that when the guards were leading me down the corridor, I would peek through the peephole in the door of cell No. 193. Guards walked in front of and behind me, and I was ordered to keep my hands behind my head and look down. Having calculated the number of steps from my solitary cell to the leader’s cell, I moved my hand and rushed to the door. Through the opening, I saw an empty cell, a lowered bunk (during the day they were usually raised so prisoners couldn’t lie down), and a table covered with a red cloth. The guard walking behind me hit me with his rifle butt, and I lost consciousness. For this violation, I was punished with five days in the cooler, but what were those five days! At least I saw the leader’s cell—who else gets such an opportunity?”

After Leningrad came Krasnaya Presnya and the Mordovian camp No. 7 for political prisoners. At that time, there were 2,500 people in the camp. Ivan Hryhorovych recounts those years: “Yuriy Shukhevych spent 34 years in the camps on behalf of his father. I was with him in Mordovian camp No. 7 from 1957 to 1961. We were friends. I have his photograph with his personal signature. The world-famous composer Vasyl Barvinsky was also there at the time. His wife, Natalia, was serving her sentence in camp No. 3, also here in the Mordovian forests of Dubravlag. Cardinal Yosyp Slipyj was also at the camp. After me, Levko Lukianenko arrived.”

The prisoners made plywood casings. Among the episodes of that camp life, Ivan Hryhorovych recalls one that could have given one of the prisoners the most precious thing—freedom. A group of Estonian political prisoners wanted to arrange an escape for their fellow countryman Bromberg, who had undergone German sabotage training during the war with the aim of continuing the struggle in the Baltics. They decided to dig an underground tunnel from the drying room to outside the zone. The earth was carried to the agricultural plot assigned to us. The work took all autumn, and the tunnel was dug beyond the fence, with only about a hundred meters left to go, but in the spring, a guard discovered a thawed patch of ground, and the tunnel was exposed.

After his release, Ivan Hryhorovych returned to Bilopillia. Like all Soviet political prisoners, he faced problems finding a job due to the relentless “assistance” of the authorities. With his sister’s help, he barely managed to get a job as a teacher in the city of Stakhanov, Luhansk Oblast.

From that time on, despite a completely new circle of acquaintances, he became actively involved in public life and graduated from Luhansk Pedagogical University.

Starting in December 1989, he began publishing articles in newspapers. Ivan Feshchuk dedicated his first article to defending Ukrainian-language schools in the eastern Ukrainian town and protecting the rights of the Ukrainian language. His subsequent articles were no less topical: research on the Novocherkassk uprising; the restoration of the historical name of the city of Stakhanov (Kadiivka); and a critique of the Soviet-era electoral system.

In the summer of 1996, Ivan Hryhorovych received a letter from the Hungarian association of political prisoners. Out of the entire former USSR, Hungary presented only three people with a national award: the Order “For the Homeland,” on the fortieth anniversary of the 1956 revolution. Besides Ivan Hryhorovych Feshchuk, People’s Deputy of Ukraine Yevhen Proniuk and Ivan Botsian, a methodologist at a teacher training institute from Zhytomyr, were also chosen. The full translation of the citation for the Hungarian order reads: “The Association of Hungarian Political Prisoners awards Ivan Hryhorovych Feshchuk, a combat comrade, the Order ‘For the Homeland,’ paying tribute to his patriotic and selfless attitude in defending the Hungarian Homeland, for which he was subjected to persecution.”

The dissidents of the Soviet era had a difficult fate. Individuals who firmly believed in the highest ideals were not valued by the state in which they had to live. (Has much changed since then, and is it not the same today?—a rhetorical question). A state that threw them in prisons, breaking their lives and crippling their fates. They could only rely on one another and move forward, without bowing their heads. And continue to believe, no matter what.