Olexa MUSIENKO. The Sixtiers: Where Did They Come From?

(Literaturna Ukraina. – 1996. – November 21. – P. 6).

DURING THE FATEFUL ERA of the so-called “Khrushchev Thaw,” while the “Cold War” was raging across the planet, the distant West was stunned by news: in the USSR, isolated from the world by the “Iron Curtain,” a spiritual rebellion had erupted against post-Stalinist totalitarianism, later to be named the Sixtiers’ resistance movement. Yet not even the most renowned Sovietologists could comprehend what this social phenomenon was, who they were—these desperate young rebels—where they had come from, how real a threat they posed to the communist regime, and what forces lurked behind them. Unfortunately, even after the inglorious collapse of the socialist camp, the phenomenon of the Sixtiers has not been properly comprehended or inscribed into the context of modern history. Only through a meticulous and dispassionate study of the ideological and political formation of the most active participants in this mass movement can we provide an exhaustive answer to these numerous questions. From this perspective, the life story of one of the founders of the Sixtiers’ resistance movement in Ukraine, Borys Maryan, is of considerable interest; his talent as a brilliant poet and novelist, translator, and publicist was destroyed in the post-Beria Gulags.

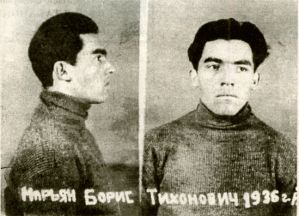

Borys Tykhonovych Maryan was born on September 27, 1936, in the village of Krasnohorka in the Tiraspol district of the former MASSR. As he wrote in his autobiography, “My parents are Moldovan by nationality. They worked on the collective farm from the time of its founding. In 1944, my father was killed in a bombing, while my brother, my mother, and I continued to work on the farm. In 1947, my older sister Anna graduated from the pedagogical institute in Tiraspol and was assigned to work as a teacher in the village of Tarakliya in the Cainari district. In 1948, after my older brother left to serve in the army, my elderly mother and I moved to Tarakliya to be with my sister, where I finished 10th grade...”

In this autobiography, Borys failed to mention that from an early age he had shown a remarkable inclination for literary work, regularly publishing his poetic attempts in the local periodicals, and had clearly defined his future life’s course: a career in the press. But where could he acquire the necessary knowledge, when at that time not a single Moldovan institution of higher learning had a journalism department? Fortunately, fate smiled kindly upon him.

In 1953, by order No. 1343 of the USSR Minister of Culture, dated July 30, following the example of Lomonosov Moscow State University, a Faculty of Journalism was opened at Taras Shevchenko Kyiv State University (KSU). It was based on the journalism departments that had functioned within the philology faculties of Kyiv and Kharkiv universities, with an approved first-year admission quota of 100 students. Having successfully passed the entrance exams at Chișinău University, B. Maryan sent a petition to Moscow to be transferred to study at KSU. In accordance with USSR Minister of Culture Order No. 623, he was admitted to the first year of the Faculty of Journalism at KSU, representing the Moldavian SSR without having to compete for a place, and was provided with a spot in the student dormitory.

Like students from other union republics, studying in Kyiv was incredibly difficult for Borys, as all subjects in the faculty (except for the geography of the USSR and, of course, the Russian language and literature) were taught in the language of the indigenous nation. However, with the help of his classmates, he successfully mastered Ukrainian, diligently studied the history and culture of the brotherly nation, and was generally known for his focus, curiosity, and diligence. He was not tempted by drink, card games, or romantic dalliances. Borys spent all his time outside of lectures in the university reading room with books and notes. It was therefore perfectly natural that after the very first semester, he became a straight-A student.

In everyday life, “Bob,” as his classmates affectionately called him, was very sociable, witty, and cheerful, and had many friends. Yet none of them had the slightest inkling that this seventeen-year-old emissary from sunny Moldova had brought a substantial body of creative work to the capital of Ukraine, that he was writing new poems and children's stories every day, and was working on completing the historical drama “Alexandru Lăpușneanu.” Moreover, he kept a diary, in whose pages he sought to make sense of events he learned about from foreign press brought by Romanian students.

Borys Maryan began to be spoken of in a loud voice not only in his faculty but throughout the entire university after the 20th Congress of the CPSU. More precisely, after that frosty March day in 1956 when students were pulled from their lectures and gathered in the KSU assembly hall, where representatives of the Stalin District Party Committee read the four-hour report delivered by the then First Secretary of the CC CPSU, Nikita Khrushchev, at a closed session of the Congress delegates on the night of February 24-25. From it emerged an image of the “continuer of Lenin’s cause,” the “father of all nations” Soso Dzhugashvili—Stalin—an image of a half-educated seminarian, a pathological misanthrope, a bloodthirsty monster who, with satanic cruelty, exterminated millions of his compatriots just to hold on to the helm of the party and state. For some of the aging university “pillars” who had reached the high echelons of an academic career under the sun of Stalin’s constitution, that March day of 1956 became blacker than the blackest night, while at the same time, hundreds of young student hearts beat with a poignant anticipation of a new era in the life of the shackled peoples of the red empire.

As one of the ideological leaders of the Sixtiers, Ivan Svitlychny, would later rightly note, “immediately after the 20th Congress, many of us had a great deal of naive, rosy-cheeked optimism, a calf-like enthusiasm, many illusions built on sand; it seemed to many that all the problems of the people’s lives would be solved in one fell swoop, and all that was left for us was to march triumphantly toward communism with banners held high.”

But the realities of life very quickly cooled the hot heads of these trusting romantics. Despite the dosed-out persecution along the party vertical of certain provisions of Khrushchev’s report and the resolution of the CC CPSU plenum “On Overcoming the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences,” in the USSR, practically everything remained as it was. As before, the sarcophagus with the embalmed Joseph Vissarionovich was guarded by a guard of honor in the Lenin Mausoleum on Red Square; as before, the Kremlin seats of the Communist Party Areopagus were comfortably warmed by the odious Stalinist henchmen Molotov, Malenkov, Kaganovich, Voroshilov, and Mikoyan, on whose consciences lay the blood of millions of innocent victims. Yet not a single open, show trial of the Yezhov-Beria executioners, of the members of the various “dvoikas” and “troikas” that rubber-stamped death sentences from lists, was held in any of the Soviet republics. Naturally, honest people began to ask: why?

Other paradoxes of Khrushchev’s “Thaw” were also surprising. Even before the 20th Congress of the CPSU, a special commission had begun its work to review the judicial-investigative cases of Stalin’s travesty of justice, and from the concentration camps and remote settlement zones, the few surviving martyrs of the Bolshevik repressions began to return to the “mainland.” But while they had been sent to the polar bears with an armed escort, they made their way home, so to speak, privately. No government officials met them, no one publicly apologized for their ruined lives; the former “zeks” were quietly given some semblance of shelter, provided with meager pensions, and… forgotten. And there was not a single case where someone who had been rehabilitated was returned, even for show, even for a week or two, to the position he had held before his arrest. And again, that accursed question arose: why?

t>The conscious citizens of Ukraine could not find answers to dozens upon dozens of such “whys.” It was obvious even to the most apolitical among them that, aside from verbal froth, no real de-Stalinization was happening in the republic. Just as in the era of the cult of personality, the pages of periodicals and various public forums slung ideological mud not only at such prominent historical figures as M. Hrushevsky, V. Vynnychenko, and O. Shumsky, but also at the cultural figures of the “Executed Renaissance.” In December 1953, the newspapers published a terse report about the execution, along with the “agent of foreign capitalism” Beria, of the Minister of Internal Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR, Colonel General Meshik, and his first deputy, Lieutenant General Milshtein. However, there was no news of hundreds of their subordinates in the Cain-like trade receiving their just punishment. The vast majority of Stalin’s executioners merely swapped their office chairs, thus hiding from the people’s wrath...

Meanwhile, the socialist camp, stirred by M. Khrushchev’s devastating critique of the Stalin cult of personality, entered a period of powerful social storms. As has happened many times in history, the younger generation, which resolutely refused to live in the “paradise” brought on the bayonets of Stalin’s “liberators” of Europe, stood at the vanguard of the fight against Bolshevik totalitarianism.

The first to attempt to break out of the socialist cage without bars was Poland, in the summer of 1956. The mass movement against Soviet occupation, led by the recently persecuted leader of the Polish communists, Gomułka, was on the verge of escalating into a nationwide armed campaign. Only through deceitful promises and major concessions did the Kremlin leaders manage to avert a revolutionary explosion by the Poles, which could have triggered a chain reaction in other countries of the “socialist commonwealth.”

Then, in October, an armed uprising erupted in Hungary. Fulfilling the will of its people, the government of Imre Nagy announced political pluralism in the country and Hungary’s withdrawal from the pen of the militaristic Warsaw Pact. To keep the Hungarians in their “fraternal” embrace, the Kremlin potentates resorted to the Stalinist method of subduing “traitors to socialism.” By order of Nikita Khrushchev, the rebel stronghold of Budapest was stormed by regular Soviet troops using heavy artillery, aviation, and motorized divisions. The Hungarian people’s aspiration for freedom and national independence was mercilessly crushed by the treads of the world's best T-34 tanks.

The party-Soviet press did not so much inform as misinform its people about these tragic events. Nevertheless, the truth about the bloody massacres in Hungary seeped through the Carpathian passes into Ukraine. The students of Kyiv University, where dozens of Polish, Czech, Bulgarian, Romanian, and Hungarian young men and women were studying at the time, proved to be particularly well-informed. The bloody events in Budapest had a truly depressing effect on them, forcing them to reflect more deeply on Khrushchev’s “Thaw.” Unorganized, often not even personally acquainted, the young dissident thinkers reached a single conclusion: the USSR would forever remain a bastion of Stalinism until the foundations of its totalitarian system of governing rightless and terror-intimidated citizens were radically changed. Sincerely concerned about the future of their homeland, free-thinking students in dormitories, dining halls, and university corridors openly discussed various options for the social restructuring of the USSR. Borys Maryan, a fourth-year journalism student, most fully articulated a package of overdue reforms in his handwritten “Minimum Program.” Here are its main points:

1. Eliminate the caste system and privileges of CPSU members.

2. Declare bureaucracy a criminal offense and wage a merciless fight against it.

3. Reorganize the Komsomol, giving it state functions.

4. Strengthen and expand the sovereignty of the republics.

5. Grant peasants land, from one to three hectares.

6. At factories and plants, transfer management to elected workers’ committees.

7. Reduce taxes by half for peasants and by a quarter for workers and the intelligentsia.

8. Permit mass rallies, demonstrations, assemblies, and other forms of civic expression, except for armed rebellions.

9. Reduce the army to a reasonable size.

10. Limit the powers of the prosecutor’s office.

11. Create councils of assessors in courts and grant them broad powers.

12. Publicize the materials of classified and publicly incomprehensible court cases from the Stalinist era.

13. Abolish censorship.

14. Grant the periodical press the right to publish different points of view on problems of economic and state improvement.

15. Do not persecute for the propagation of different philosophical, aesthetic, and legal views, except for openly nationalist and fascist ones.

16. Permit the distribution and sale of foreign books, newspapers, and magazines.

17. In international affairs, continue the struggle for peace and cooperation with all countries of the world.

18. Introduce the practice of broad transparency for all government negotiations and agreements.

19. Permit free exit from and entry into the country for all citizens who wish it.

20. Grant complete autonomy to universities.

21. Provide students with a scholarship that would guarantee a medium standard of living.

Being a self-critical person, Maryan understood the imperfection and limitations of this series of measures for renewing the USSR. Therefore, during an evening lecture in mid-December 1956, he gave a few classmates his draft to read and offer critical remarks, wishes, and suggestions. Only five of Maryan’s benchmates hastily read the manuscript of the “Minimum Program,” but this was enough for Borys to be urgently summoned to the university party committee the next morning.

Of course, if a year earlier he had shown such a product of his imagination to even two “friends,” he would have been hauled off in a “black raven” to a KGB investigative detention center that very night. But in December 1956, the echo of Khrushchev’s revelation at the 20th Party Congress had not yet died down in the world, and the “competent organs” no longer dared to resort to the repressive methods of the Stalinist era at the first opportunity. That is why they entrusted the university party committee to deal with the free-thinking fourth-year journalism student. There, Maryan was asked to show the “secret document” he was circulating among his fellow students. Without any fear, the future poet-prose writer-playwright took the draft of the “Program” from his student briefcase and placed it on the party committee’s table, stating that he was submitting not some “secret document” for the respected body’s consideration, but a preliminary draft of a letter to the CC CPSU, “written personally by me with the aim of helping the party and Nikita Sergeyevich personally to democratize and improve our society, and to raise the standard of living of the Soviet people to international standards...”

News of the “Minimum Program” spilled out from the university walls and, thanks to the diligence of the official informers, reached the office of the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (CC CPU), O.I. Kyrychenko. According to contemporaries, Oleksiy Ilarionovych was a typical despot of the Stalinist mold and resolved all problems instantly, “with his fist and foul language.” Back in the summer of 1956, when a report from “overzealous” officials landed on his desk stating that too many bourgeois nationalists had proliferated at the capital's university and that their main breeding grounds were the history, philosophy, economics, and journalism faculties, Kyrychenko, in a fit of rage, demanded that the KSU Academic Council “immediately shut down the vilest faculties.” It took several respected party-affiliated scholars to cool the CC CPU First Secretary’s anger with a word of caution: the unexpected and legally unjustified liquidation of even one KSU faculty would be a tacit admission that the CC CPU had allowed anti-Soviets to build a “hostile nest” right under its nose. This, they warned, would certainly be exploited by imperialist propaganda and by the hidden enemies of the CC CPU leadership... But when, in mid-December 1956, industrious aides slid Maryan’s “Minimum Program” before Oleksiy Ilarionovych’s eyes, he literally went berserk: were the university wiseguys seeking a repeat of the Hungarian events?! And a secret operational report was slashed diagonally with a red-penciled resolution: “Investigate to the very roots!” And that meant the floodgates were opened for the repressive organs...

Like the vast majority of his classmates, Maryan had already been under the surveillance of KGB informants, but after “Comrade” Kyrychenko himself took an interest in his person, he found himself under a true siege: a secret search in his student dormitory, meticulous perusal of his correspondence… However, the decisive role in exposing B. Maryan’s “anti-Soviet core” was to be played by a denunciation. For the KGB, which had a whole staff of informants in the Faculty of Journalism, producing one was no problem: on December 19, a “statement” of the following content arrived at 33 Volodymyrska Street:

“I consider it my duty to report to you that, as a result of observations of the 4th-year student of the Faculty of Journalism, Borys Maryan, I have established the following:

1. In 1955, in auditorium No. 367, I found a notebook of B. Maryan’s poems in which he in every way denigrates the poetry of our prominent poets K. Simonov, S. Shchipachev, and others. Almost the entire notebook is imbued with a spirit of disbelief in the strength of our system, in the truthfulness of our literature. His poems are reminiscent of the ideologically empty, hostile poems and stories of Akhmatova and Zoshchenko, which were duly appraised by our party.

2. I and many students have noticed that during lectures, Maryan B. interprets what the instructor says in his own way. He disagrees, refutes what is said...

3. Working on the editorial board of ‘Linotype,’ ‘Negative,’ and ‘Butterfly Net with a Net,’ B. Maryan repeatedly put forth slogans: ‘A newspaper—without communists!,’ ‘Long live the freedom of the wall newspaper!’

4. During a trip to the Virgin Lands (summer 1956), Maryan and Damaskin wrote a letter to N.S. Khrushchev about the incorrect system of educating our journalism students. Maryan believes that the party organization and the dean's office pursue a policy of intimidation, not allowing students to develop.

However, neither the Komsomol nor the party organizations of the faculty have taken any measures regarding Maryan to date.

As a communist, I consider it my duty to report this to you.”

Beneath this “document” was not the pseudonym of some scruffy anonymous writer, but the real signature of the course party organizer, Mykhailo Chornyi. It is worth noting that M. Chornyi was ten years older than B. Maryan, had already served six and a half years in the army, and had enrolled at KSU as a member of the CPSU. He did not distinguish himself with any particular academic success but gained a reputation in the faculty as a master of staging public reprimands of his classmates at party meetings. For this reason, the student body openly disliked him, though they also feared him, considering him a secret informer.

M. Chornyi’s “statement” was fabricated in the style of the Stalinist era; in the recent past, it could have served as grounds for a “dvoika” or “troika” to hand B. Maryan, if not a death sentence, then at least a long-term imprisonment in concentration camps. However, by the end of 1956, the situation in the country that proudly called itself the “bastion of socialism” had changed. Since September 1953, the Supreme Court, in accordance with a Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, had been reviewing, upon the protest of the Prosecutor General, the illegal decisions of the OGPU collegiums, “special conferences,” and military tribunals of the MVS troops; from mid-1954, central and local commissions were constantly at work, created to study the cases of citizens convicted on political charges during the years of mass repressions; hundreds of half-murdered “enemies of the people” were returning from the camps. Thus, under the new conditions, M. Chornyi’s denunciation could serve as a basis for initiating criminal proceedings against B. Maryan, but it could not be regarded as convincing proof that the student had committed illegal acts. More substantial arguments were needed for the rebellious student’s arrest and prosecution.

And the KGB analysts very quickly found such “arguments.” In fact, they didn’t even look for them but used the tried-and-true model of the so-called “Sormovo workers’ initiative,” which the Kremlin leaders ruthlessly exploited when implementing unpopular state measures, such as issuing another government bond, raising or introducing new taxes, extending the work week, and so on. The most monstrous discriminatory actions were carried out precisely at the “demand of the working masses.” In the repressive scenario where Borys Maryan was to be the main character, the KGB analysts assigned the role of the “working masses” to the author of the “Minimum Program’s” own classmates.

To express the will of these “working masses,” a pre-scripted Komsomol-party meeting of the fourth-year students was convened on January 7, 1957. To it, senior officials from the CC CPU, the Ministry of Higher Education, and the city party committee “coincidentally” dropped by; also in attendance were the university rector, Academician Shvets, half the members of the party committee, and the entire faculty leadership, along with, of course, the “tough” guys from the junior years. A single issue was on the meeting’s agenda: the civic and political conduct of student B.T. Maryan. Admittedly, in their frantic haste, the organizers of this mass spectacle made a significant legal error in the agenda.

The fact is that on December 28, 1956, when the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR initiated a criminal case against B.T. Maryan, the leadership of the Faculty of Journalism—without waiting for even the preliminary conclusions of the investigation and without properly assessing the “Minimum Program”—sent a memorandum to the rector of KSU, in which it asserted: “Recently, there have been repeated politically harmful statements on the part of the 4th-year student B.T. Maryan, aimed at undermining trust in the policy of the Communist Party and the Soviet government, as well as separate hostile attacks that not only discredit the title of a student of a party faculty, which the Faculty of Journalism is, but are generally incompatible with the high principles and morals of a Soviet young person. Maryan's unworthy behavior was unanimously condemned by the faculty community. The Dean’s Office of the Faculty of Journalism considers the further presence of B.T. Maryan at the university impossible and asks the rector's office to expel him from the student body of the faculty as a person who is ideologically immature and unprepared to fulfill the honorable duty of a Soviet journalist.”

After reading such a supplication, Academician Shvets, with his order No. 2 of January 4, 1957, granted the “request of the Dean’s Office of the Faculty of Journalism,” expelling B.T. Maryan from the university with the justification: “as one who has disgraced the high title of a Soviet student.” Thus, at the time of the Komsomol-party meeting, that is, on January 7, Borys Maryan was, for his former classmates, effectively a man off the street, meaning they simply had no right to discuss his behavior, let alone pass any resolutions. Yet for some reason, they were not informed of rector’s order No. 2, and the meeting began at the precisely scheduled time.

The tone of the discussion, as was to be expected, was set by the secretary of the faculty party bureau, Associate Professor V.A. Ruban. An experienced former party functionary who in the post-war five-year period (1948-1953) had managed to climb the rungs of the Central Committee apparatus from head of the literature and art department to the super-influential position of assistant to the First Secretary of the CC CPU, he outlined with just a few phrases the channel in which the denouncing passions were to boil. “Maryan and his like-minded followers have fallen for the bait of our enemies,” immortalized the words of Volodymyr Andriiovych in the protocol of that unique tribunal. “There is no place for such anti-socialist, counter-revolutionary elements in the university. And especially not in the Komsomol.”

Ruban’s baton was picked up by the course party organizer, M. Chornyi: “Maryan ‘showed his colors’ back in his first year. And his ‘Program’ is by no means an accidental mistake, but a deliberate counter-revolutionary attack,” he declared. “Damaskin fully supports Maryan, so we must also talk about him. To allow such rot in our collective is a crime. We must expel Maryan from the Komsomol and kick him out of the university. And Damaskin along with him!…”

And so it went, one after another. Yesterday’s classmates rushed to brand their comrade with political labels—the one who dared to put down on paper what many of those present were secretly thinking. Borys tried to defend himself, proposed that they listen to his “Minimum Program,” but it was no use—he was simply denied the floor. Seventeen people took the podium, and the refrain of every speech was Gorky’s sinister aphorism: Maryan is an enemy, and enemies are destroyed! One after another, the regular, trained-in-pogrom-and-denunciation Komsomol activists jumped up to the lectern and, as if from a template, mercilessly branded their classmate, not mincing words, calling down the most terrible punishments upon his head, as if it had already been irrefutably proven that he had committed the gravest crime. And the rank-and-file students sat in cowed silence, their gloomy gazes fixed on the floor…

Maryan tried to refute the absurd fabrications and insinuations, to at least briefly acquaint those present with his package of proposals to the CC CPSU on reforming and improving Soviet society, but Chornyi and Co., seated in the presidium (the names could be deciphered, as both the protocol itself and the people who wrote it have survived—but to hell with them!), immediately deprived him of the floor. Above all, the organizers of this “meeting” feared that the content of Maryan's “Minimum Program” would become known to the students. After all, the vast majority of them were from the lower strata of society, who had found themselves within the walls of the capital's temple of science only by an unforeseen coincidence—Stalin's death and the opening of the Faculty of Journalism at KSU. They knew the charms of Stalin's “paradise” from their own bitter experience and, according to intelligence reports, openly desired the destruction of the totalitarian system. So where was the guarantee that at least half of those present, upon hearing the main points of Maryan's “Program,” would not want to add their signatures to it? And it was absolutely necessary to portray Maryan to the public as some kind of eccentric, a social outcast who had no support in the student environment...

But even after silencing Borys, the instigators of this “act” failed to achieve their goal. Amidst the clamor of vilification, for example, the thoughtful words of the aspiring Russian-language poet Ivan Pashkov were heard: “I have long known Maryan as a gifted person. Coddling him, of course, is not necessary; he needs to be persuaded. He has told me more than once that he would be glad if someone could argumentatively dispel his doubts about our surrounding reality. In my opinion, expulsion from the university and the Komsomol is too harsh a punishment for him. He needs to be given time to think things through…” Even more radical was the proposal of a former locksmith from the Kharkiv Tractor Plant, Volodymyr Damaskin: “If, in the opinion of the authorities, Maryan deserves to be expelled from the university for his proposals to the CC CPSU, then this should be done to 90% of all KSU students.”

To prevent passions from flaring, Academician Shvets hurried to the lectern. “I declare before the face of our Party's Central Committee that our youth is reliable,” the rector of the capital's university clearly addressed his words to the representatives of the “high authorities” who were alarmed by the speeches of Pashkov and Damaskin. “I have seen many enemies. When they were taken by the throat, they cried and repented. Enemies are pitiful people. They have no homeland. This rot must be resolutely liquidated!”

And yet, despite the rector's own explicit call for a crackdown, the specific proposals so hoped for by the organizers of this “Sormovo” spectacle were not made at the fourth-year students' Komsomol-party meeting. As if in a cruel twist of fate, at that very moment, they were being voiced in the office of KGB special investigator Zhylenkov by the then dean of the faculty and were recorded verbatim: “I consider it necessary to state that Maryan must be immediately isolated, as his presence at the university has a corrupting influence on the students.”

Nevertheless, the “working masses” had done their dirty work, and all that was left for the KGB was to hear their “legitimate” demands and draw practical conclusions. While the vilified Maryan was returning books to the library, de-registering from military service, and canceling his temporary registration in Kyiv, preparing to leave as soon as possible for the Virgin Lands development in Kazakhstan, the state security specialists were writing the “Resolution on the Choice of a Measure of Precaution” for the seditious student and securing a sanction for his arrest from the Deputy Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR, Ardyrikhin. And on January 12, 1957, at 11:45 p.m., they arrived in a “black raven” at the university dormitory on Solomianka and, accompanied by the commandant S.I. Ivanov, burst into room No. 28, where six future journalists lived. Having confirmed which of the young men was B.T. Maryan, they presented a search warrant and methodically began to inspect his belongings. Although what belongings could a poor student have, when he wore all his property on his person… However, the nocturnal visitors were not interested in Borys's things, but in his papers. As noted in the official protocol, during the search, the security service operatives seized eleven separate manuscripts from B.T. Maryan. Namely: the novel “Green Dniester,” the children's novella “Where the Stars Go Out,” a general notebook with the inscription on the red cover “Poems,” the scholarly work “The Shchors Zhytomyr Partisan Division,” an interlude in six scenes “My Children, Oh, My Children,” the folk tale “Natka the Partridge and Her Little Brother Vitka,” the historical tragedy “Alexandru Lăpușneanu,” the short story “The Letter Arrived Late,” a thick notebook with diary entries, prose sketches without titles, and a notebook with various drafts for future works...

In the KGB investigative detention center, where B. Maryan was brought by convoy at dawn on January 13, no one beat him, no one even threatened him. Following standard procedure, they conducted a personal search, opened an investigative case file No. 49, placed him in a solitary cell, and very correctly proposed that he write a detailed autobiography. It was in that unnatural-for-a-prison-cell correctness that he intuitively sensed a prepared trap, so he wrote everything he knew about his father, Tykhon Fedorovych:

“I know that in 1919 he was the chief of staff of a partisan organization in Moldavia that fought against the communists. After that rebel detachment was crushed by Kotovsky's troops, my father fled the village of Malaeshty to avoid punishment. Nevertheless, in 1930 or 1931, he was arrested. Upon his return from exile, he spoke out against collectivization. My brother Alexander has been a Komsomol member since 1933 and took an active part in implementing collectivization. On this ground, he had quarrels and disagreements with our father… He reported him to the GPU authorities, for which my father was exiled from Moldavia to the Arkhangelsk region. After his return, Alexander left the family and broke with his father forever. He now works as a collective farm chairman.”

The romantic-reformer did not know what a “deep plowing” of his family history the Kyiv investigators were conducting. Even before his arrest, official information from the Moldovan KGB was already filed in his case folder, stating:

“In 1944, Maryan, Tykhon Fedorovych was sentenced by a division's military tribunal to 10 years in a Corrective Labor Camp for the fact that, while in temporarily occupied territory from March 1942 to March 1943, he was in the service of the Romanian authorities as the chief of gendarmes in the village of Krasnohorka… And also conducted anti-Soviet agitation among the population.”

After classifying the background from which B. Maryan came, the investigators' interest in him immediately waned, although for two months they persistently tried to find out when Borys conceived the idea of the need for the social restructuring of the USSR, who his ideological inspirer was, and with which KSU students or teachers he discussed and compiled the “Minimum Program.” To the arrested man's credit, both during exhausting interrogations (there were 16 of them!) and in face-to-face confrontations with his classmates, he invariably asserted: always and everywhere I observed a cascade of flagrant outrages in daily life, and it was precisely to eliminate those shortcomings that I prepared a package of proposals to be sent to the CC CPSU. I wrote my proposals independently, without inspirers or co-authors...

The investigators had no choice but to wait for the conclusions of the expert commission on the political and ideological substance of the “Minimum Program” manuscript. However, the experts—Candidate of Philological Sciences V.Y. Shubravsky and Candidate of Historical Sciences F.K. Stoyan—did not live up to the KGB's expectations.

“The manuscript consists of 27 points containing recommendations for the partial restructuring of the socio-political order in our country,” they wrote in their “Conclusion.” “The title word ‘minimum’ gives reason to think that this is a rough draft of only minimal demands, dictated by the author's dissatisfaction with certain aspects of our life and the desire to indicate what should be undertaken to improve matters. The overwhelming majority of the points testify that their author belongs to the number of politically immature and naive people who easily succumb to all sorts of provocations. All of this has been indiscriminately borrowed from the arsenal of hostile foreign propaganda and provocative rumors.”

The experts seriously criticized and debunked B. Maryan's quixotism, but they did not qualify his act as a malicious action of an enemy of the people. On the contrary, they courageously made the following “CONCLUSIONS”:

“1. The ‘Minimum’ manuscript does not contain direct attacks against the Communist Party, the Soviet government, and our people. But objectively, in its content, in its ideological and political orientation, some of its points express an ideology alien to the Soviet system, unlawfully demanding the restructuring of certain aspects of the socio-political life of our country.

2. The author of the manuscript does not have a definite, clearly expressed program. His work represents a mixture of various rumors about the ‘world abroad,’ known to him only by hearsay, and the slanderous fabrications of the reactionary press and radio about the USSR.”

With such conclusions from respected experts in hand, even an investigator of the lowest qualification would have considered it a matter of professional honor to close Maryan's case for lack of corpus delicti. But before the inner eye of the Ukrainian KGB leaders loomed Kyrychenko’s menacing red-penciled resolution “Investigate to the very roots!” and they ordered their subordinates to search for those “roots” in the literary work of the disgraced student.

To anatomize Borys Maryan’s handwritten works, a reviewer was appointed: Yu. Skrypnychenko, head of the literature and art department of the newspaper “Kyivska Pravda.” But even he could not fail to note that the “pieces submitted to him for political analysis are evidence of Maryan's literary abilities. Certain passages are not devoid of a certain artistry. But on the whole, his works are still very imperfect in both form and content. The author clearly lacks a firm, coherent worldview… B. Maryan's poems turn out better. They contain fresh images, their language is rich, their rhythm light and musical. The author also succeeds in satirical verse. And yet, B. Maryan is as if constrained by something. What prevents him from singing with a full voice?” And the reviewer finds an unappealable diagnosis: “He has given himself over to anti-Soviet, counter-revolutionary fabrications, usually spread by the agents of international imperialism.” As an irrefutable argument, he quotes a line from a poem: “Oh, my black-eyed Moldavia! Where are you? You are a small and honest girl, raped by pot-bellied bureaucrats, by legitimized Arakcheyevs and Unter-Prishibeyevs…”

But what truly enrages Yu. Skrypnychenko is the young poet's hope for a better future for his native people: “I know: the Savior of the beautiful will come to this Gomorrah (note: Gomorrah - a land of debauchery). Await the advent, stupefied people!” In a pogromist style borrowed from the Stebunivs and Sanovs, the reviewer writes about Maryan’s notes under the heading “New Political Jokes”: “He writes down all sorts of filth, vomit here. If he portrays Stalin in a most disgusting light, he also turns the great Lenin into a character of an anti-Soviet joke.” Based on his own rejection of the fledgling writer's ideological principles, the KGB-hired reviewer reached the following conclusion: “It's not about the facts, but about the tendency. And that, unfortunately, for this young man, is counter-revolutionary from beginning to end.”

It was precisely this legally untenable assertion that formed the foundation of the indictment, which, after being approved by prosecutor Ardyrikhin, became the “bill of indictment” and, along with the criminal case, was sent to the Kyiv Regional Court for consideration.

Both during the investigation and at the trial, which took place on April 25, 1957, the accused, Borys Maryan, conducted himself with dignity and fearlessness. He did not repent for anything and did not grovel before the judges, begging for mercy, but responded with dignity to the falsified accusations: “I admit that some points of the so-called ‘Minimum’ that I composed contain an ideology alien to the Soviet system and are partially aimed at restructuring the socio-political life of our country, but by this I wanted to improve our society, democratize it, and better the welfare of the people. In the ‘Minimum’ I set forth my opinion and my proposals, but I did not engage in their dissemination. The fact that I gave my ‘program’ to friends and some other students, including communists, to read—I do not consider that propaganda, as I gave it to them to read so that they would give me their assessment and help me to sort out these issues...”

The Kyiv Regional Court, presided over by Yevtiukhov, following the usual script, rubber-stamped the sentence dictated from the higher echelons of power: to imprison B.T. Maryan for a term of 5 (five) years in corrective labor camps, without deprivation of civil rights.

The defendant’s lawyer, L.I. Izarov, immediately appealed to the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR with a cassation complaint, in which he irrefutably argued: “If we consider that he (Maryan) gave this ‘program’ to the secretary of the KSU party organization, then one must conclude that in this case, Maryan lacked counter-revolutionary intent. Some points of this document (the struggle for peace, etc.) could not have caused objections, which is why the expert analysis notes that only some points express an ideology alien to us. Thus, we are dealing with ideological errors, not a crime.”

However, the judicial collegium for criminal cases of the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR, which was predominantly composed of disguised Stalinists, upheld the measure of punishment chosen by the Kyiv Regional Court for the politically conscious citizen B.T. Maryan...

Having dealt with the naive reformer of the totalitarian system, student Borys Maryan, using a method established back in the days of Stalinist terror, the Kremlin leaders (for it was by their secret order that the “taming of unruly troublemakers” was carried out behind closed doors in the USSR!) hoped to uproot freethinking in Ukraine. They did not want to, or rather—could not believe that many of his university classmates harbored views far more radical than Maryan’s, and that the most talented among them—Vasyl Symonenko, Vasyl Zakharchenko, Vadym Kryshchenko, and others—already had in their modest creative portfolios works that echoed the wrathful word of Taras Shevchenko.

Due to their ideological blindness, they ignored the fact that the young generation, still in the mother’s womb, had genetically inherited the Ukrainian people’s age-old striving for freedom and independence; that from the cradle, it was imbued with the nationwide sorrow at the memories of the bloody whirlwind of the civil war, the mass deportations of the best farmers to the land of “polar bears,” the Holodomor of '33, and the total Stalinist terror; that this generation had, in its childhood, endured the Hitlerite invasion, post-war hardships, and brutal repressions for a potato or a corncob taken from a collective farm field; that this generation was entering conscious life already rejecting the charms of the Stalinist “paradise.” But consumed by internal squabbles, the inspirers of Khrushchev's “Thaw” failed to notice how, on the historical stage, there appeared not eccentric Maryans, but ideological comrades-in-arms like Levko Lukianenko and Lina Kostenko, Ivan Koval with Bohdan Hrytsyna (both shot during Khrushchev’s “cold snaps”), with Ivan Drach and Mykola Vinhranovsky, Ivan Svitlychny and Panas Zalyvakha, Ivan Dziuba and Yevhen Sverstiuk, Alla Horska and hundreds of other conscious patriots already on their way...

...The forerunner of the Sixtiers had to serve his undeserved punishment in the sinister Mordovian concentration camps. It was in the “universities” there that he finally shed his boyish illusions that the existing totalitarian-anti-human system in the USSR could be somehow patched up, democratized, given a human face. To reassure himself of his conclusions, he sent a letter to Khrushchev's CC CPSU: “The 20th Congress melted the ice of fear and silence spawned by the cult of personality. Everyone began to speak at once—friends and enemies, the embittered and the indifferent. They spoke about everything, no one thought they would be punished for it. The leniency from above led to the tragedy of Hungary. Hungary horrified me, I became more restrained, but... For ‘criminals’ like me, all the prisons in the country would not have been enough...” No answer, of course, ever came.

After toiling for 5 years in the Mordovian taiga, Borys Maryan emerged from the camp zone gravely ill, but with the scales fallen from his eyes. Deprived of the right to reside in the capitals of the union republics, he settled in his native village. Under the close watch, of course, of the KGB's agent network. He survived on odd jobs, dedicating all his free time to literary work, with no hope of seeing his words published. Only with the collapse of the USSR did the invisible walls of his spiritual prison crumble. He became the editor-in-chief of a leading Moldovan newspaper and, in his final years, published several of his own books. But the main book of his life, about the origins of the Sixtiers’ resistance movement, we believe, is still awaiting its time.

Scanned and proofread by Vasyl Ovsienko on October 2, 2007. Photo from “Literaturna Ukraina,” 1996, November 21.