We are publishing the transcript of a lecture by the human rights activist, publicist, religious scholar, and one of the founders of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, delivered on December 8, 2010, in Kyiv at the House of Scientists as part of the “Polit.ua Public Lectures” project. The “Polit.ua Public Lectures” is a subsidiary project of the “Polit.ru Public Lectures.” The project features talks by leading scholars, experts, and cultural figures from Russia, Ukraine, and other countries. The lecture is published in its Ukrainian original and a Russian translation.

Kadenko: Good evening, dear friends. We are beginning our Polit.ua lecture—as always, in this hall at the House of Scientists. I'd like to remind you that this season, our lectures are supported by Alfa-Bank Ukraine, and our speaker today is Myroslav Marynovych…

Dolgin: …a very well-known human rights activist, religious scholar, and vice-rector of the Ukrainian Catholic University.

Kadenko: Yes, thank you. And we are your hosts—Boris Dolgin (Polit.ru) and myself, Yulia Kadenko (Polit.ua). And the topic of today's lecture is “The Spiritual Training of the Gulag.” Please, Mr. Marynovych.

Lecture Content

Myroslav Marynovych: Thank you very much for the introduction, and greetings to all the participants of this meeting today. It's a pleasure to see faces I already know, but also a pleasure to see the faces of those I don't know—for that is the joy of meeting.

Today's lecture will be an attempt to present to you a tapestry of memories, but not for the sake of memories as such. This is not an evening of reminiscences about “the deeds of days long past”—these are memories for the sake of extracting some life wisdom, some moral lesson. These are part of the bricks from which I built my worldview, but also from which the people around me built theirs. This genre also gives me an opportunity to remember my friends from the camps and from outside. Time passes, and I see from my interactions with young people that, say, they still know the name Viacheslav Chornovil, sometimes responding, “Yes, we know, we’ve heard of him.” But the name, for example, of Nadiia Svitlychna is unknown to many. The era of the dissidents is receding into deep history, and one could joke: for the youth, if these people don't have avatars on Facebook, then there's nothing to be done about it; these people don't exist in the minds of young people either.

So today I want to show many photographs—these are pictures of people who are alive for me, from whom I learned a great deal. Because, in principle, we were teachers to one another. But although I learned a great deal from my camp friends, all of these, in the end, were lessons from the Lord. So, I want to say right at the beginning that I am a Christian, and I will be speaking about spiritual training from a Christian perspective. This, of course, does not mean that I disregard the religious experience of other people who were in the camp, people of other faiths. On the contrary, it would be very interesting someday to compare this diverse religious experience. And everyone did have it, because the camp was a place where a religious worldview naturally and закономірно took its place in people’s minds. It first came as an antithesis to the dominant atheistic worldview that prevailed in the Soviet Union at that time. In the camp, it was fashionable to be a believer—if only because the odious Soviet state was atheistic. But fashion passes quickly, and when your life is tied to various challenges and sufferings, this religious experience very quickly acquires the right and authentic overtones.

In prison, there are no intermediaries between God and man. This is a special feeling that cannot be recreated or simulated in freedom. Believe me, I often regret that I cannot have the same feeling now. In the camp, there is a kind of “short circuit” between the human soul and God. It's like cosmic rays. On Earth, there is an atmosphere, so cosmic rays don't reach us, because the atmosphere shields people from them. On the Moon, there is no atmosphere, and cosmic rays reach the planet's surface directly. It is much the same in the camp: nothing stands between God and man. This is especially noticeable when you spend a long time in solitary confinement. I had the feeling that, in contemplating the world, I saw the globe before me and all the processes taking place there. I was as if outside, somewhere to the side. In space, there is only the globe, God, and you. This is a special feeling that, I repeat, cannot be artificially recreated.

It is not by chance that I mention space, because the remoteness of the camp (at least the Kuchino camp in the Perm region, where I was) created special effects—the sky there was special. It was clear and unclouded, not separated from you by any industrial landscapes. I once lay down on a bench and gazed at that magnificent sky. And imagine—that sky simply falls upon you, and you become imbued with it, with those planets that are very close to you. For some reason, this effect of the sky's closeness is especially powerful in the Urals. And you feel as if you are the first Adam. One night, it even frightened me to think that the first Adam to appear on this Earth probably gazed at the sky just like this.

I deliberately wanted to begin with these emotional moments, which convey the inner state of a prisoner in the camp, before talking about my interactions with people. And now, allow me to return for a moment to the pre-Gulag period, during which I was forming as a dissident. Here, too, there were challenges, there was a certain spiritual training.

Everyone who wants to live a dignified life must overcome fear. Without this, you cannot preserve your dignity, because you will eventually make compromises that will harm your moral backbone. For me, a turning point was the KGB's attempts to recruit me as an informant. It all started with fear, great fear, because I was a young, inexperienced boy. Suddenly, you are faced with a dilemma: either you agree to become an informant, or they will kick you out of the institute in your third year. It is understandable that a person looks for compromises, on the one hand, to avoid expulsion, and on the other—not to cross the line of the permissible. Well, my conclusion is this: such a compromise is impossible. Sooner or later, it will turn into a great moral challenge, and so you will be forced to make a choice and choose your path.

For me, that moment was May 22, 1973, when I went to the Shevchenko monument in Kyiv with two friends. I'll remind you that laying flowers at his monument on this day meant signing a confession of one’s own nationalism, as the call to honor the Poet on the day of his reburial in his native land came from the Ukrainian diaspora. With me were Natalia Yakovenko, today one of Ukraine’s most brilliant historians, and Mykola Matusevych, then a future political prisoner and member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

So, as a trio, we approached the Shevchenko monument. There were no people yet, as we went in the morning. But the KGB officers were doing their duty diligently; they had been watching the monument since dawn, so they photographed us, and an hour later I was taken to the police at the Zhuliany airport, searched, and asked the sacramental question: “For what purpose did you go to the Shevchenko monument?”

When I returned from a business trip to Ivano-Frankivsk, where I was working at the time, I was immediately summoned by the head of the 1st Department of the KGB, who told me that I was engaged in explicit anti-Soviet activity and therefore had to choose: “He who is not with us is against us” (a reinterpretation of the famous words from the Gospel). And I, then a young man, replied: “Fine, I will be against you.” I don’t know where I found the courage to say that. It seems only youth can answer like that. Because today I would say, “Well, you know, on the one hand, I’m against you, but on the other hand, I’m for you”—and so on. I would look for some roundabout, academic formulas to define my position. But then I said those decisive words: “Fine, I will be against you”—and I freed myself from fear. What a magnificent feeling that is! It’s a wonderful lesson, and when a person goes through it, some unexplored spiritual forces are unlocked within them. You are capable of doing much more than before.

My life in Kyiv at that time was connected with many people. I do not aim to mention now all those people who surrounded me at that time. For instance, I couldn't find a photograph of, say, the Yashchenko choir, though at that time I was acquainted with many of its singers. I will mention first of all Atena Pashko, who is present here, and Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska.

At that time, Viacheslav Chornovil, Atena Pashko’s husband, was already in prison. But the story of their tormented love was particularly moving for me. In fact, that was my Kyiv: either those dissidents who hadn't yet been imprisoned, or the families of those who had. It was in this circle of friends that I was formed.

I recall one lesson from Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska that was especially important to me. It had a backstory. So, I became a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, and how I wished that more and more people would sign its petitions! It was an irresistible desire. You have already set out on this path of struggle, and how you want more people to join you! (A similar desire can be seen in the eyes of the participants of the “entrepreneurs’” Maidan in Kyiv. They stand there, freezing, and dream that all of Kyiv would stand beside them. It's such a natural desire!). So, I would suggest to people that they sign our documents, somehow pushing away the thought of what it might mean for them, not thinking about whether they were ready for the sacrifice. I don’t remember who the person was then, but I remember well that I was somehow pushing them to sign our document. Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska called me and read me the riot act, as they say. She even came up with an aphoristic formula for me: “One must love not all of humanity, but specific people.” These true words instantly put me in my place. Think, my boy, not only of your own interests as a member of the Group—think about each living person, who has their own special “bouquet” of fears and courage.

The next lesson is from Oksana Meshko.

By that time I already knew this glorious woman; in particular, I knew of one wonderful moment from her life. Oksana Yakivna once told me how she was tried by a Stalinist troika. The judge told her (of course, he spoke in Russian, but I don't want to imitate it): “You are so young, beautiful, so alluring, but after prison you will be old, hunched, sick.” And Oksana Yakivna straightened up and said proudly: “I will never be hunched!” Time passed. One day she was walking the streets of Kyiv. “Indeed,” she says, “I’m walking, old, weak, stooped, it’s hard for me, and suddenly I see—coming towards me is the same judge who sentenced me. I instantly straightened my shoulders. No, I thought, you will not see me hunched!”

So, one day in the streets of Kyiv, Mykola Matusevych and I met Oksana Meshko. And she told us: “Boys, we are now organizing the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. We have people who are tied to one place, either due to their health or other matters. But you are young, mobile—would you not like to join us?” And she added: “If you decide ‘yes,’ then come tomorrow to Koncha-Zaspa to Mykola Danylovych Rudenko’s at this address.” And she ran off. And we walk on, understanding that we have to make a very important decision. If we say “yes,” then sooner or later it means arrest. There were no illusions about that. If we say “no,” it means we will feel self-contempt and pangs of conscience for the rest of our lives. So we decided “yes,” arrived the next day in Koncha-Zaspa, and everything started rolling from there.

What lesson did I learn from this? That day began for me just like any other weekday. Nothing promised anything extraordinary. But it turned out that on this day I made the most responsible decision of my life. So, one must live each day with the readiness that today you might make the most responsible decision of your life. There will be no additional signals, no hints; you must be ready always—perhaps even this very evening.

Here are the names of the founding members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, its first ten: Mykola Rudenko, Petro Hryhorenko, Oksana Meshko, Oles Berdnyk, Levko Lukianenko, Ivan Kandyba, Nina Strokata, Oleksa Tykhy, Mykola Matusevych, Myroslav Marynovych.

Now for the lesson from Levko Lukianenko… Due to our youth and mobility, Mykola Matusevych and I indeed became couriers. Mykola traveled to Moscow to see Yuri Orlov, the head of the Moscow Helsinki Group. I also went there to see General Hryhorenko, but right now I will tell you about my visit to Levko Lukianenko in Chernihiv.

This is a man who was legendary even at that time. For creating an underground group of lawyers who contemplated the possibilities of Ukraine’s secession from the USSR, he was sentenced to death (by firing squad), and then this sentence was commuted to 15 years of imprisonment, which he served in full, from bell to bell. And imagine: while still under surveillance, he was not afraid to become a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, that is, to risk arrest again. For me, this was an amazing testimony. So I came to him in Chernihiv, and at some point, the following conversation took place between us: “Do you understand that you will be arrested?” asks Lukianenko. I say, “Yes.”— “And are you ready for it?” — “Well, yes, of course, I am.” How often I later recalled those words in moments of weakness, fatigue, and despair! His question resounded within me constantly. And how important it is that we ask people such questions at a responsible moment in their lives! Even if the person answers them somewhat hastily or artfully—it is important that these questions will constantly echo in their soul.

Now for the lesson from General Hryhorenko.

In the winter of 1977, I went to see him in Moscow. As a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, I understood that the KGB was monitoring my movements. I am walking the streets of a vast, snow-covered Moscow and thinking to myself: “Well, what are you doing here, my boy? You are just a tiny insect (and you understand that in Moscow it is especially clear how enormous the power of the authorities is). Who are you going up against?...” But I arrive at General Hryhorenko’s apartment—and all that dreadful, snowy feeling recedes. Because you see a Man, or as Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska often says, an upright man—Homo erectus. This man knows how to stand straight, despite the fact that some force is trying to bend him.

Petro Hryhorenko taught me to be sensitive to the national feelings of every wronged nation. Yes, at his home I saw Crimean Tatars, who simply adored him. His appeal to the Crimean Tatars is well known: “Take back what belongs to you by right, but was illegally taken from you.” He likewise rushed to the defense of Ukrainian national feeling. I once sent him a telegram to Moscow, and it was delivered to him translated into Russian, although I had sent it in Ukrainian. And he did not let this pass—he wrote to the USSR Ministry of Communications, demanding the right for a telegram sent in Ukrainian to be delivered in that language within the Soviet Union.

To be in the company of such people is a wonderful thing. Then you feel like a human being, you feel brave…

And what happens when these prison gates slam shut behind you?

It has a strange effect. I immediately felt this change when I heard the specific sound of the cell door slamming: that’s it—you’ve been locked up, and you realize you are all alone, and there are no other people for whom you play certain social or political roles. You have no one to lean on. Before you is only the investigator and the KGB machine in all its power. And you have to get down to the business that is truly yours. These doors very clearly separate what is yours and what you are ready to fight for, from what is not yours, what is superficial. It was then that I had to first recall those words of Levko Lukianenko: “Are you ready?” Now you have to give a real answer to yourself, whether you are ready for the struggle. The court case began, but I have no time to tell about it, because I want to move on to another experience, when you learn to resist attempts to humiliate you. During the investigation there were similar attempts, but they were still very delicate, as this was Kyiv, the central KGB prison, you are addressed as “Vy” [the formal ‘you’]—all these are remnants of that previous world. But then I find myself in a so-called “stolypin”—a special railcar for transporting criminals.

Here I begin to learn about a side of life I had never even suspected before, namely: how prisoners are treated. For the first time in my life, I saw how, during boarding of the “stolypin,” a group of prisoners was surrounded by dogs, how one had to obey commands like “get down,” “sit down,” and so on. And in this “stolypin” itself I experienced a real shock. (Please forgive me for the excessive naturalism, but I want you to fully feel this transition from the relatively normal life of a defendant to the life of a prisoner under guard). I was being transported from Kyiv to Kharkiv. They took us to the “latrine” only once during the entire trip—in the morning, just before Kharkiv. As an “especially dangerous state criminal,” I was held in a separate cage. When they announced that we should prepare for the latrine call, I took a small towel, draped it over my arm, took a toothbrush, toothpaste, and soap—and waited for them to open the cage. The soldier who opened it stared at me, dumbfounded, and began to cover me in a hundred-story-high string of curses. I couldn't figure out what I had violated, but I followed his gaze and realized that he was irritated by what I was holding in my hands. Well, okay, if it's not allowed, I'll put it aside. They lead me to the latrine area, and then it begins to dawn on me that no one had any intention of letting me wash. Washing is “not permitted,” and brushing your teeth, no less! You are no longer a person—you are a zek, someone who can be humiliated. And there were no doors at all in this toilet. “Sit down,” he pointed his machine gun at me, “do your business.” And that was precisely the moment when you have to understand: either you will be internally destroyed by this humiliation, or you will say to yourself what our political prisoners said: “No, they will not succeed in humiliating me.” And indeed, after that, it becomes easier for a person. This training of a political prisoner lasts for so long that even today it is very easy for me at any moment to switch to worse conditions. Of course, it is pleasant to be in a five-star hotel, but psychologically I am ready to find myself even in the worst living conditions. I can preserve my dignity anywhere.

As an example, I will tell you one more story about a seemingly sordid affair into which prisoners managed to bring a special spirituality (forgive me for breaking the chronological order of the narrative). Among us, the political prisoners, was a Russian poet, Viktor Nekipelov.

His birthday was approaching, and we were all in the punishment cell—we had been punished once again. And we thought: how to congratulate Viktor, what gift to give him? We are in the punishment cell, we have none of our belongings. But we have something more important: our minds, and a sincere and creative soul. And we decided: each of us would come up with a poem for him, or at least one stanza, and tomorrow we would read him these poems. But how to read them to him—he is in another cell? But every zek knows: the sewer, the latrine bucket, serves for communication. And the poet Mykola Rudenko, myself, and all of us in turn lean down to the latrine bucket and read our poems to Viktor Nekipelov. And on the other end, he is crying with emotion. Because it is a beautiful moment: none of us smells the odor, none of us sees anything, but is experiencing a great moment of spiritual uplift. This is what the human spirit can do.

But let's return to my transport to Kharkiv. There, in the transit prison on Kholodna Hora, a simple murderer taught me an important lesson.

They bring me, a young, inexperienced zek, into a cell where another prisoner is sitting. We started talking, I tell him about my criminal case, he tells me about his. I must say that a certain brotherhood develops in relations between prisoners, as another prisoner has the same status as you. So I listen to him very sympathetically, nodding my head at his every phrase, and he describes a situation where there was one scoundrel of a man who bothered everyone. And then he says: “And one day I couldn't take it anymore, I took a bottle, hit him on the head and killed him.” I froze with my nodding. I realized I was facing a murderer! And he says to me: “But evil must be destroyed, right?!”

Now, if anyone ever says that phrase to me: “evil must be destroyed”—the association with that murderer instantly comes to my mind.

And so I finally arrive at the 36th camp in the village of Kuchino in the Perm region. They put me in quarantine in this SHIZO building (punishment isolation cell), where I stayed for a week. Once a day they would take me out to the “exercise yard.”

One day I am walking there when a small window in one of the barrack's windows opens, and I see not a face, but lips: “I am Semyon Gluzman. And who are you?” I introduce myself: “Myroslav Marynovych.” “Did you know that all members of the Helsinki Groups have been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize?” I say: “No, I didn't know.” The walk ended, I return to my cell—and a very interesting period begins… When we get vaccinated, we inject a portion of bacteria into our bodies so that the body can find the strength to overcome the infection and develop immunity. In the same way, the Lord injected a small dose of the temptation of fame into me that day. Returning to my cell, I thought: “A Nobel laureate! But is my jacket big enough to pin that Nobel Prize medal on? And will they let us out for the ceremony?” In short, my head was full of nonsense. But how good it was that I went through this week of a kind of vaccination! Later, when they released me from quarantine into the camp, I entered its real atmosphere and finally said to myself: “Come on, man! That's enough—we’ve arrived.” And thank God that since then, having had many opportunities to be tempted by fame, I have proven to be resistant to it. And I am very grateful to God for this period of temptation, because it produced in me a kind of “antibody” to fame.

Now about something else—about bitterness. When I was about to be transported from the pre-trial detention center in Kyiv, the prosecutor asked me: “What is your goal for your future life?” I answered: “Not to become bitter.” Today it seems strange to me that even in Kyiv, under investigation, it was important for me not to become bitter. And in the camp, I saw very clearly two roles that every prisoner can choose for himself.

In the camp, there were bitter people and there were radiant people. This is especially clear in the case of two former UPA soldiers. In the end, I will name only the person with a positive outlook—Pavlo Strotsen. I will not name the bitter hero—is he solely to blame for his fate turning out as it did?! I immediately felt that I did not want to turn into a person who is constantly seething with hatred—I wanted to be completely different. So, seeing those roles personified was extremely important for me.

I will speak of the lessons from Yevhen Sverstiuk, who is present here. They were important for me because the camp turned out to be far from the ideal place I had imagined. For me, even while I was free, all those imprisoned there were already heroes—they were my ideals. And now, having been among them, I see real people, capable of conflicts, who sometimes reveal far from the best facets of their nature. One had to find ways to resolve such conflicts. I remember once, Mr. Yevhen and I were walking along our “Ho Chi Minh Trail” and talking, when a Crimean, Oleksiy Safronov, approached us and told us about another conflict. “It must be resolved somehow—but how?” Mr. Yevhen listened and then said: “Of course, on the basis of the Gospel.” I remembered these words for the rest of my life, because until that moment I had lived somehow divided: one layer of life—religious (it was somewhere out there, beyond reality), and the other layer, on the contrary—completely real, earthly. These layers somehow did not intersect, or at least I was not aware that they intersected. But here, in Mr. Yevhen's words, they intersected—and it turned out that to solve the problems of the lower layer, one can and must apply the norms of the upper layer! This was a real spiritual revolution for me. I thought a lot about those words and even experimented with their practical application.

Another story is connected with Yevhen Sverstiuk—how I became a Russian monarchist.

Once, Yevhen Sverstiuk and Yevhen Proniuk were taken from the zone and placed in quarantine in the same SHIZO building before being sent into exile.

It was January 6, 1979, right on Christmas Eve. I see that the little window in their cell is open, so I think, let me go closer, as far as the barbed wire allows, and sing a Ukrainian carol—maybe they'll hear it. I start to sing, and when the guard heard it and came out, I stopped, so as not to make a demonstration out of a religious carol, and went on my way. The next day, the operations officer summons me and says: “I have a report here that you were violating the rules.” He reads: “…Sang monarchist songs.” We look at each other in surprise, and neither of us can understand a thing. According to my sentence, I was officially a “slanderer of the Soviet system,” but in reality, the authorities perceived me as a “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalist.” And now, suddenly, “monarchist songs”… When I realize what’s going on, I start laughing hysterically. The guard had come outside just as I was singing: “O you, King, King, Heavenly Ruler…” from the carol “A New Joy Has Come.” Well, if they're singing about a king, it’s all clear: “Marynovych sang monarchist songs.”

How to be firm in your principles? In the camp, this is very important—not only to assert yourself, but also to show others that you have firm principles. Here, Zinovii Krasivskyi taught me a great lesson; he shattered all my possible stereotypes.

He is a legendary figure. Firstly, his love for Ukraine stemmed precisely from love for her, not from hatred for her enemies. I never saw hatred in him. This was unexpected, because even today we can often see nationalists who have based their feelings on hatred for those they perceive as enemies. Secondly, I noticed with surprise that he spoke with the KGB agents calmly, even sometimes joking with them: “Ah, good day! Good day, Mr. Surovtsev!” (our camp KGB agent was from the Ternopil region, so it was possible to speak Ukrainian with him). I myself, like many others, had up to that point chosen a very principled, as I thought, position: “I do not speak with you, for you are my enemy.” But here comes a man to the camp, who is serving his third sentence and whom it is impossible to suspect of being an inexperienced zek. Finally, I ask him: “Mr. Zinovii, are you not afraid that your actions in the zone might be misinterpreted?” He looked at me with a little smile in his eyes and said: “And you, don't you trust yourself?” I was speechless: it turns out it’s that simple! One should not play roles for others, but be oneself, act as one’s conscience dictates. Such a simple formula, but for me, it was, again, revolutionary.

Now about the lessons from Valeriy Marchenko. Before his arrest, he was a Kyiv journalist, altogether a wonderful and free person who shaped himself daily throughout his short life.

Some very important moments of my time in the camp are also connected with him. One time we had planned to hold a protest hunger strike for some Soviet holiday. He knew about it because he was with us, but the day before they snatched him from the zone and transferred him to the hospital. Our situation changed, and we decided not to hold the hunger strike, but to resort to another form of protest. And so we did. After some time, Valeriy was returned to the zone, and he asked, “Well, how did the hunger strike go?” We explained: “Well, we replaced it.” “How did you replace it? We had an agreement, I was on a hunger strike in the hospital…” I don’t remember ever blushing in my life as I did then, when I looked into his eyes. We just hadn't thought about him, we were sure that he wouldn’t go on a hunger strike alone. Because he had kidney disease, a hunger strike for him was something incredibly difficult. And this inner aristocratism of his stunned me. There is a rule: the true aristocrat is not the one who eats with a knife and fork in public, but the one who changes for dinner and uses a fork and knife even when alone. Valeriy Marchenko, may his memory be a blessing, was precisely such an aristocrat of the spirit.

And another lesson from him. How many dramas Soviet people (not just Ukrainians) experienced when the KGB persecuted the husband, the family's breadwinner—and the family pressured him to stop the struggle, to compromise. And some indeed gave in, suffered various moral losses, and then suffered themselves. Valeriy Marchenko wrote a beautiful letter to his mother on this subject. Here is a small excerpt from it:

How can I preserve my respect and love for my mother, how can I not ruin myself in the name of our beautiful relationship? I do not want to join the many who, unable to withstand the trials and having strayed from the path of morality, resort to the saving argument “we are not the only ones.” You are my only one, and I do not want to listen to anyone or anything suggesting that for the sake of biological existence near my mother, I can spiritually cross myself out. I hope that you, after thoughtful consideration, will agree with me. Does a mother really need a moral cripple who, when asked “did you live the previous 30 years in delusion?” would have to borrow shamefaced eyes and… agree, muttering something about illness, about unbearableness? Is this the kind of life to wish for a son? I do not believe it!

And Valeriy performed a miracle: after his death, his mother was left practically alone, and you can still see how dignifiedly she carries herself. And though her son has long been in the next world, how he straightens her spiritual posture! Valeriy consciously made a sacrifice. But I would not want you to see in this any tendency to be a kamikaze or a desire for suicide. It is simply the ability and capacity to draw a demarcation line between good and evil, to say to evil: “I am ready to compromise, but only up to this point, only to this line. And beyond that, I will not compromise.” And though evil continues to press on you, pushing you towards new sufferings and even to death, you do not go beyond that demarcation line.

…Yes, I need to wrap this up, because I have clearly overstayed my time. How much longer can I speak? Five minutes at most?

Dolgin: As long as you need.

Marynovych: Oh no, because then you might not be able to stop me…

Well, alright, a few more words about the lessons of political prisoner Oles Shevchenko, later a People’s Deputy of Ukraine of the first democratic convocation.

There were, in fact, two lessons. One of them seems to echo the lesson of Valeriy Marchenko. Oles, who for a long time had not received letters from his wife, was once summoned to the camp’s KGB agent. The agent told him: “Your wife is gravely ill. She will surely die, and you have two small children—you must take care of them. So either you write a letter of repentance now, and you will be immediately released to your children, or we will send the children to an orphanage, and you will never be with them again.” It was hard to look at Oles during those few days they gave him to think. Yet he refused to write such a letter, trusting in God's will. And a month later it turned out that it was all a lie: his wife was healthy and the children were safe. It was just a vile KGB trick. How happy Oles was that he had made the right decision! Formally, he had seemingly sacrificed everything—the last visit with his wife, his children. But a compromise with his conscience would have been an even heavier catastrophe for him. This is how harshly evil worked on us.

And the second moment. It was through Oles Shevchenko, in fact, that I began to write. He once called us out to the yard, where he read his poem, which was based on a real story. While still in Kyiv, he had called an ambulance to get a doctor for his sick mother. He spoke, of course, in Ukrainian, and in response, they told him: “Speak a human language”—otherwise they would refuse to send a doctor. So Oles’s poem expressed great pain and great hatred—it was an accusation against Russia. On the one hand, I understood his emotions and agreed that he had a moral right to react that way. But I did not want then, and I do not want now, to build the future of my people on hatred. So, in response to his poem, I wrote my first camp piece, namely: “The Gospel According to the Holy Fool.” Why “Holy Fool”? Because I was in a camp where anger towards one's oppressors was supposedly a normal thing, but I was writing about love and forgiveness. It was in the camp that I formulated my position that hatred should not be our path.

Just a few more words about my closest ones. Only in the camp do you realize how dear your relatives are to you, what a huge support they are for you.

My mother and sister are no longer in this world, they have passed on, but they continue to be a spiritual support for me. My wife Liuba came to me in exile as a friend, and we married there, in Kazakhstan. She left Kyiv and essentially repeated the story of the Decembrists’ wives. I am very grateful to her for that.

I must skip the lesson of Mykola Danylovych Rudenko. It is an interesting story, but it is very long. I will not have time to tell it.

Instead, I will mention the story of the letter to the Pope of Rome.

One year, we decided to celebrate Easter in the camp—to mark the holy day with prayer over tea and simple sandwiches. Beforehand, the administration announced that we would be punished for it. Well, for Christians, to be punished for celebrating Easter is a normal thing. We were indeed punished—they threw everyone they considered organizers into the punishment cell. In response, we decided to write a letter to Christians all over the world, addressing it to Pope John Paul II. At that time in the West, the “Christians for Peace” movement was spreading, and the Soviet Union actively participated in it, supporting it both in the media and materially. We were struck by the duplicity of the Soviet authorities, for at the very same time that the Soviet Union was supporting Christians in the West, here in the camp, we were punished merely for having prayed on Easter. For some reason, I was entrusted with writing the draft of this letter, and I wrote it (it is, by the way, now on the Internet). Subsequently, Pope John Paul II did receive our letter and prayed for us during Mass. It was very beautiful.

I must finish now. I will just show the photographs of the women political prisoners who played an important role in my life. I still keep in touch with those who are alive.

Here is Oleksa Tykhy, whom I saw in the last days of my imprisonment. He was a wonderful man; he died almost immediately after our meeting—I was probably the last of our group to see him.

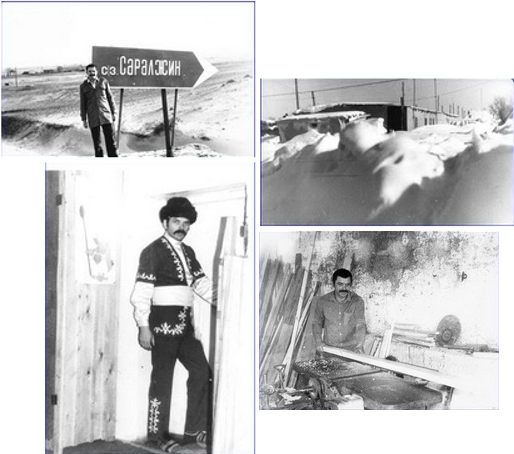

And here are a few of my photographs from exile.

I would like to end with a very beautiful poem by Viktor Nekipelov, whom I have already mentioned:

Говорили: тюрьма – это стон озлобления,

Утверждали: она – цитадель безнадежности.

Но тюрьма – это символ любви и смирения,

Это высшая школа надежды и нежности.

Is that really possible? Can a prison be such a place? Yes, it can, but on one condition: if you are innocent. If there is no sin or crime upon you, then it is indeed possible.

And one last thing. When I was finally released, I soon felt a certain restlessness. I began to miss something. At first, I didn't realize what it was, but then I understood: in the camp, or even in exile, my every day was justified. It was justified by the fact that I was serving an unjust punishment. But when I was released—all that suddenly disappeared. Now, I had to earn God’s approval every day, to do some good to earn my “supper.” And then I understood the meaning of those words from the Gospel, which we often consider an exaggeration:

Блаженні гнані за правду, бо їхнє Царство Небесне

(З Нагірної проповіді Христа, Мт. 5:10).

When you are persecuted for the truth, then God invisibly helps you and becomes your support. And you perceive this support as something absolutely natural and quickly get used to it. And when you return to freedom again, it doesn't mean, of course, that God abandons you, but He no longer props you up as He did when you were persecuted for the truth. And you feel this. Only when this feeling recedes do you realize how significant those words are for you and how important that spiritual support was, which God gave you…

Thank you very much for your attention. Please forgive me for making my speech too long.

Lecture Discussion

Dolgin: Thank you very much! Perhaps Mr. Yevhen Sverstiuk… No, not a question. Perhaps a few words from you?

Sverstiuk: I would like to thank Mr. Myroslav for systematizing the lessons of the zone through personalities. Indeed, these lessons remain for a lifetime because they were experienced in special conditions, in special trials. I wanted to say about the tempering that people who have principles and faith receive there; but the zone is not a tempering for everyone. For those who came there with faith or converted to faith there—undoubtedly, everything works for the good. But for those who ended up there not entirely consciously, against their will and inner motives—imprisonment is not beneficial and it corrupts them. The camp corrupts a person who is not formed and has no core within them.

I thought about Zinovii Krasivskyi and how he spoke quite riskily with the KGB agent. In the zone, this is not evaluated unambiguously, and you cannot explain your behavior to everyone, but how directly and somehow effortlessly he developed such a style of humane relations with everyone. I often thought about him. It was easier for me, as for Mr. Myroslav. I am a writer who wrote, according to his convictions, what, in principle, should have been published. Mr. Myroslav also wrote petitions that a normal government should have at least read. But Krasivskyi was an underground fighter, he published the underground journal “Volia i Batkivshchyna” (Will and Fatherland) and dealt with enmity—you know, “at bayonets’ point” with investigators. If he had called things by their proper names, there would have been a short circuit between them every time. And so, he converted them to humanity with his kind smile. The KGBists could have destroyed him during the 21 years he was in captivity. But this kindness and benevolence of his were his protection.

I think this is a very important lesson in our life, where there is so much evil and so many overt and covert enemies, both open and simply foolish ones—it is extremely important to have an organic Christianity.

By the way, I would like to add a cautionary note here about Christianity—or not Christianity, but religiosity. We were very solidary with people of other faiths. For instance, Zionists like Iosif Mendelevich or Arye Vudka were much closer to me than the liberal Makarenko, also a Jew. Because a man of faith is one of your own, there is a prior agreement with him regarding the main truths; a man can be trusted when he has true faith. And nothing has changed to this day. It is extremely important when a person’s nature is crystallized around such a core as faith….

Dolgin: A question regarding what Mr. Yevhen said. In your opinion, Mr. Myroslav, why did Varlam Shalamov believe that the camp brings nothing good, that one should not look there for what makes a person better? How does this correlate with your experience?

Marynovych: Thank you. I probably wouldn't agree with that, though I also understand that sometimes my stories about the camp can have a strange effect. Once in Drohobych, they listened and listened as I talked about it, and then they said: “Oh, so it means it was possible to live in the camp.” Of course, people died there; of course, they were punished there. I just don't escalate the atmosphere with those negative moments. But they certainly existed.

I personally had a moment when I thought I was about to die. They packed three prisoners, including me, into that cage in a Black Maria, a cage that could barely fit one person. And the little slits, which are meant for breathing through, couldn't provide enough oxygen. And we had to breathe like that not for a few minutes: we were driven on a transport route for several hours on the great Ural road—with pits and potholes. It was impossible for all three of us to stand: someone had to squat at the bottom, and someone had to stand on top of the others. And this mess of people was tossed from one side to the other as this “van” drove, in absolute suffocation… I thought these were my last moments. To my credit, I must admit, I didn't say to myself then: “You did this in vain.” I am very glad I didn’t have that feeling.

Of course, there are many harsh moments in the camp. And as Mr. Yevhen said, there is a very strong spiritual field there; a person cannot be just between good and evil, they must choose: either to go towards good, or towards evil. There is no middle ground. I think that for some, including Shalamov, the experience of being in the camp was different—perhaps they saw more of man’s fall. But I saw so much that was good, that was radiant. I saw so many people rise to the heights of their spirit that I understand Viktor Nekipelov and can repeat his words.

University Medical Professor: Dear Mr. Myroslav, I read your latest article in the press and was captivated. In this article, the nation’s intellect speaks to us today. I have a question for you. You talked about how people were reforged in the camps, in what was actually a terrible misfortune. I have been teaching at the medical university for 44 years, and I see that young people are now in despair. I am already departing from this life, my age is the last century. Our youth is the new century. How can we make it so that for the youth, Ukraine is at the pinnacle of their love for her? How can we pass on that experience of yours? I believe that what you are saying now, you should be heard in the opera house, and students not only from your university, but from my university, and many others should be sitting there. But how can we do it—not with hatred, I understand, but with what force, the force of good? How?

Marynovych: Thank you. You know, it will come. I have no doubt that today's youth will find themselves, find their own answer to these problems. The current state of society is quite interesting; it intrigues me myself. Today’s youth is convinced that making a sacrifice is a formula of past eras. Why make a sacrifice? Well, how long can one go on making sacrifices? One man in Kyiv told me at our meeting: “Mr. Myroslav, our answer to your problems is this—you need to properly fill out a grant application, get the money, and do what needs to be done. This is the formula of our time, of our generation. We don’t need sacrifices.”

Dolgin: Excuse me, who needs it? Do what needs to be done for whom?

Marynovych: A modern young person believes that one should not make a sacrifice, but simply make proper use of available resources and opportunities. I am not against it. I am for a society where everything could be settled by a proper distribution of resources. It seems this is the ideal world, which lives according to God's laws and in which there are no crises. But we live in the real world, where sin churns and multiplies, and if it is not removed from society, it will be like the toxins that remain in our body and contaminate it. And how to remove these toxins if they are not removed on their own? Only through sacrifice. This is a formula that determined even God Himself. For God, to change humanity, sent His Son to be sacrificed (according to the Christian view). So, this is at the foundation of the world, and we must understand that if we do not want to make a small sacrifice today (meaning that someone might be fired from their job, someone’s salary might be reduced, someone might have to move to another city, etc.), then we or our descendants will be forced to pay with a very large sacrifice. In general, events are now developing so rapidly that, most likely, we will also be paying. So, the choice is ours. I hope that young people will poke around here and there, looking for paths, will try to get by without sacrifice, and then they will understand that it won't work that way.

It seems to me that there is still more optimism than pessimism in our society right now. I was a great pessimist in the summer of 2004, but the “Orange” Maidan changed everything. And this current Maidan, the “entrepreneurs’” one, did a very important thing—it removed fear from society. Anything can still happen, but there is no longer that fear of the 1937 model, which had appeared in many during the first months after the new government came to power. Thank you.

Kadenko: Mr. Myroslav, do you think there is anything in Ukraine today similar to the dissident movement in terms of spiritual level?

Marynovych: Ukraine needs moral authorities. It needs people who can model and illustrate certain moral truths in their behavior. But for now, there is only talk, and there are no such people at the national level. Almost everyone talks about the decline of spirituality, from presidents down to our neighbors and ourselves, but how difficult it is for us to manifest this spirituality in real life! As a result, we have what Golovakha, the Kyiv sociologist, called an “amoral majority,” for whom to act according to moral principles means to be a “loser.” So, in such a world, where an amoral majority reigns, the emergence of people who are capable of demonstrating a different model of behavior has enormous weight. Especially when a critical mass of such people gathers, enough to change the situation.

Kadenko: So far, there are no such people?

Marynovych: I consciously do not call the current protest movements dissidence, because for me, dissidence means that a totalitarian regime exists in the country. There is no totalitarian regime in present-day Ukraine, so there cannot be the kind of dissidence that existed in Soviet times. But there can and should be various forms of protest against the duplicity or lawlessness of the authorities. The more of them there are, the sooner we will have a civil society, the more order there will be in our state, the fewer mistakes the government will be able to make.

Leonid Shvets, “Gazeta po-kievski”: Mr. Myroslav, I have a question about two correlations. The first correlation: I recently spoke with Semyon Gluzman, who served seven years in the camps and three in exile. He says that Ukrainians made up about 40 percent of the Gulag prisoners (this refers to the time when he himself was “serving”). He says he did not see a single Belarusian there, except, perhaps, for policemen from the war times. There were no Azerbaijanis either, and so on. He explains this phenomenon for himself by saying that Ukrainians have such a ferment of resistance. This is a rather irrational answer. Do you have a rational answer?

And the second correlation: both you and Mr. Yevhen spoke about people of high spiritual quality, and at the same time Mr. Yevhen said that there were also those who went there and faced their own despair. What was the approximate ratio of the steadfast to the despairing? The ratio of those who only grew stronger there to those who lost faith?

Marynovych: Thank you. Both questions are quite difficult to answer rationally. Regarding the first question—that observation is fair. I also have the feeling that Ukrainians were the majority in the camps. I never felt homesick for Ukraine in the camp. Firstly, there were many with whom I spoke Ukrainian. Secondly, the outlines of the Ural Mountains are very similar to the outlines of the Carpathian Mountains… I can even say that communicating with those people was a spiritual luxury. They were my second university, a university of life. And so I even wanted to go there, to have the opportunity to communicate with those people and be a part of their lives.

Why were there so many Ukrainians there?... Let’s compare the levels of persecution. There used to be such a comparison… I probably won’t reproduce it exactly; maybe Mr. Yevhen will help.

Voice from the audience: “In Moscow, they’d snip your fingers; in Kyiv, they’d chop off your hands.”

Marynovych: Something like that. Or: “What in Moscow is a disturbance, in Kyiv is a revolution.” The longest and harshest sentences were handed down in Ukraine. Our Ukrainian KGB tried so hard. Perhaps this generated a corresponding reaction. I don't know, I can't explain it rationally (perhaps sociologists would find some explanations), but I think that Ukrainians had a very keen sense of national grievance. And social grievance too, for that matter, because, say, in eastern Ukraine, in the Donbas, people also rose up for workers' rights.

Secondly—regarding the ratio of steadfast to despairing prisoners. I never asked myself such a question. I can only say that in my circle of acquaintances, there were more people for whom imprisonment was a formation of character, an overcoming of some fear, a different perception of suffering than before. Their suffering built them up. Although I agree that in many cases, suffering can destroy a person, and completely at that.

Oleksiy Panasiuk, “Spadshchyna” Ukrainian Studies Club of the Kyiv House of Scientists: Mr. Myroslav, do you know anything about the American commission of 1929 that investigated signs of violence against people, that is, the conducting of terrible physiological experiments on people and the construction of secret roads toward the Finnish border? Have you seen the report of this commission? I have the impression that the American side concealed the results of this commission's research.

Marynovych: Thank you. No, unfortunately, I am not a historian and I am hearing about the existence of this commission for the first time, but I think that the American side either concealed or overlooked many things in the history of the Soviet Union. For us in the camp, for example, it was laughable to recall Eleanor Roosevelt’s visit to the USSR, which was permitted by the Soviet authorities. She knew that people were being punished and tortured in the camps here, and, as an American, she wanted these people to at least have a Bible. Knowing this, the NKVD organized her visit to one prison, where Bibles and Korans were lying in the cells. Mrs. Roosevelt saw this and was absolutely naively delighted that religious rights were being provided for in the Soviet Union. But as soon as she left, those books were immediately taken away again… In our time in the camp, it was strictly forbidden to have any religious literature. When, at my request, Ihor Kalynets in exile rewrote the Sermon on the Mount for me and sent it in a letter, after some time our camp KGB agent met me and said: “A-ha, Marynovych! I’ve figured out your plan! I know this is the Sermon on the Mount, and this letter will be confiscated from you.” And that was that.

Sverstiuk: I would like to say a few words in defense of the Belarusians. There were Belarusians in the zone, and I remember two of them. One was imprisoned for participation in the UPA, but that was also a Belarusian movement, a solidary one. A very decent man. And I remember a second one: also a very decent and very fine man, who was fighting off red partisans to save his cow. They were driving her into the forest, and he grabbed his rifle and fought the cow back. For which he got 15 years. I must also say that among Belarusians, though not to the same extent as among Ukrainians, there was resistance. Obviously, there was some persecution there, but Masherov pursued a policy of appeasement, and it is clear that there was not such sharp resistance there. I am familiar with Belarusians from the PEN Club, I often traveled there; there are very distinct personalities and distinct moods there.

And I wanted to add one more lesson. Do you remember, Mr. Myroslav, Mykola Bondar was imprisoned with us? Or was he not with you? No? He was a postgraduate student who, during a demonstration at the celebration of the Great October Socialist Revolution on Khreshchatyk in 1968, held up a sign that said “Shame on the CPSU!” Alone! Clearly, that’s character. He was, of course, knocked off his feet, taken to an ambulance, and immediately given seven years.

I remember a conversation with him. He was a very pure man, but not a principled fighter by nature—his sense of justice prompted him to fight. Once he had just come out of the punishment cell; 15 days is always very hard, and here the boys were up to something (there is this zek-ish, political or organizational stubbornness). He was supposed to sign something there, so that he would get another 15 days. They often did this, especially those who were about to be released from the camp, because they would be released anyway; and in general, they needed a wider range of experiences, well, and some kind of biography. I approached Mykola, pulled him away from the boys who were egging him on to further resistance, offered him something, and he said a phrase to me that still resonates within me: “I understand when a man is offered bread, but I don't understand when a man is offered a hunger strike.” This is a formula, a whole formula.

Dolgin: Thank you. I’ll add how quickly the Belarusians remembered their white-red-white flag when the new Belarusian state emerged; so, there is a nationally conscious intelligentsia there.

Representative of “Russkaya Mysl” in Paris: A small question about your time in Kazakhstan. I had a meeting with some elderly people, I remembered one elderly Kazakh. I met him recently, and he said that his brightest memory is how they would see the zeks off to work and back and throw what seemed like stones at them. But they weren't stones, they were hard Kazakh sheep's cheese…

Marynovych: Thank you for this question, because it gave me an opportunity to say a little about the period of exile. I really like Mr. Yevhen Sverstiuk’s definition that Kazakhs are very close to nature and very far from politics. They are a special people in that they accept you if you respect their customs. They accepted me literally in the first few days, although in the minds of many I was just a criminal: they gave me food, because I was dropped off there with just a backpack. True, one official, in response to my question, “And where will I live?”—answered: “Look at you, such a criminal, and you still want to sleep somewhere!” (I will add right away that later, after my release, he came to visit me in Drohobych). Overall, the people treated me very kindly: they brought food, they helped. A few months later they asked the local policeman: “Can we invite him to a wedding?” He answered: “Has he done anything bad to you?”— “No.”— “Well then, why not invite him?”

I will give one interesting example of the Kazakhs’ attitude towards me. In the village where I was—Saralzhyn—there is a contest for the best song, the best performance, at the New Year celebration. I took part in this contest, I sang a Kazakh song (you saw me in the photo in Kazakh clothes), and they gave me third prize. And I thought to myself: “Would this have been possible in Ukraine?” Would it be possible that in Soviet times, in some average Ukrainian village (with the exception, perhaps, of a village in the Carpathians), some Kazakh political prisoner would be so accepted as to be given a prize for performing, say, a Ukrainian song?... The Kazakh people have a certain dignity. They have a very patriarchal way of life, there is great respect for elders. So for me it was a very interesting period of my life and a very good one in terms of relations with the local population.

Question: I have re-evaluated a lot in my life after meeting you. I read your and Semyon Gluzman's book of memoirs, there was a third author there. Do you know which book I mean?

Marynovych: The third author is Zinovii Antoniuk. The book is called “Letters from Freedom.”

Question: It made a very big impression on me, and I am grateful to you… But it reminds me of a tired old Soviet joke: “Lenin was revived, brought from the mausoleum to the politburo. He asked for a file of the newspaper ‘Pravda.’ He read it. A short time later, they looked into the room, and he was gone. On the table was a note: ‘Gone to Switzerland to start all over again.’”

Two days ago, I spoke with representatives of the Helsinki Group here in Kyiv. Well-fed, content, living by the principle: “every cricket knows its place.” What is this?

Voice from the audience: The Helsinki Group or the Union?

Question: We have nothing to defend in terms of human rights. Whose money do they live on, what kind of people are they?

Marynovych: Most of my camp brethren are now infirm and old people. When we met in Kyiv for the 30th anniversary of the Helsinki Group, it was simply painful to look at many of them—they have changed so much; and my conscience would not allow me to demand any civic or political activity from them.

Voice from the audience: ….no desire to help…

Marynovych: Ah, I just misunderstood you. Because I would rather call myself well-fed. The young human rights defenders have their own duties and their own challenges. Without a doubt, among them are those who are disingenuous, who use the idea of human rights defense to get grants and simply travel to seminars and amuse themselves. I know such human rights defenders from my own experience, and this phenomenon pained me greatly. But at the same time, I know young people, human rights defenders, who stand quite firmly on these positions. I think that perhaps it’s just the circumstances now, there is no totalitarian regime and none of the circumstances that strike sparks. I don't want to turn into a person who says that everything was fine in the past, and now everything is bad. There is something good, and something bad.

Yuriy Protsenko: Mr. Myroslav, you spoke all about heroism, valor, but I want to talk about betrayal. One of the founders of the Helsinki Group was Oles Berdnyk. And he repented. I am not really a historian and do not know the history of the dissident movement well, but I like to “sit” on the Internet. I read some materials there by Berdnyk’s daughter—Myroslava. What she writes is pathologically anti-Ukrainian. After the daughter, I got to the father. And I found out that Oles Berdnyk was imprisoned twice. Once under Stalin, the second time—already with you all. So, the first time he was not imprisoned for nationalism, but one could even say for internationalism… His letter of repentance, which was once published in “Literaturna Ukraina,” is not on the Internet. I would like it if you could tell a little about this.

Marynovych: Alright, thank you. In principle, this is a very interesting story. It has many facets. I met Oles Berdnyk when he was being persecuted, when he was a rebel. He was a very significant figure. He was tall, with long gray hair, he spoke very expressively, with dignity. I admired him. And after the arrest of Mykola Rudenko, Berdnyk was the de facto head of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. He testified at my trial. He spoke wonderfully. His first phrase, said in a thundering voice, was: “What are you trying him for?” The judges were furious that he had acted as the judge, not them. But then, in the camp, he broke. And I explain this by his psychological characteristics. Oles Berdnyk was a tribune-like person, a preacher who needed an audience. He could not live without an audience. Here he is arrested and put in a camp, and as a recidivist at that. And in the cell with him were not listeners; there sat those who were themselves leaders. Those who were thinking about the future Ukrainian government and “distributing portfolios” in a future Cabinet of Ministers. Therefore, his statement of repentance was psychologically motivated for me, I understood him. Although, of course, it was very unpleasant when our camp KGB agent ran around the camp with that newspaper, urging us: “Here, read this, do the same, and you will be released just like him”... I was already in exile when I saw on television how Oles Berdnyk was speaking on the slopes of the Dnipro, the wind blowing his hair, and next to him a bandurist was playing and singing. For a Ukrainian heart—a very touching picture. The bandurist sings, and Berdnyk talks about how he fell for the provocations of the Americans and the West and how he now regrets it… But I want to end the story about him with this. Look how strangely the Lord dealt with Oles Berdnyk, and compare his last days with the last days of Mykola Rudenko. In his final years, Berdnyk had a serious illness. He could not speak. He, a brilliant preacher, was struck dumb; he could only write on a slate and communicate with people that way. Mykola Rudenko, who did not betray, had very poor eyesight, he was almost blind. But he himself writes that the best sight is spiritual sight. Rudenko’s spiritual sight was opened. In the end, in his last year, his eye, which had been injured since childhood and had never seen anything, even it began to see a little bit. And in the persons of these two people, I see God’s action very clearly. So, you chose betrayal, right? And you were struck dumb. But you did not choose betrayal, and spiritual vision was opened to you. This is very telling for me.

Oleh Shynkarenko: Tell me, Mr. Myroslav, what do you think about the founder of the WikiLeaks site, Julian Assange? Today he is the most famous dissident of global scale and, perhaps, a political prisoner. He was arrested for rape, although in reality we know that governments all over the world were displeased that he publishes secret information on his site. Do you believe he is a prisoner of conscience? Or are those right who believe he was doing business on a scandal?

Marynovych: Thank you. I do not think that the Western system of justice has become so “Sovietized” as to resort to the same methods that the Soviet Union once used. I think that the figure of Assange is quite complex and he, perhaps, is not without some psychological quirks. But I dare not say anything substantive about whether his sentence is just. I simply have no information. But I can comment on this situation with a proverb… I forgot who it is that shouldn’t drowse—the carp or who?

Voices from the audience: “The pike is needed so the carp doesn’t drowse.”

Marynovych: Thank you. So, such people and such sites are needed so that governments do not drowse. And so that they, so to speak, watch what they say when they think no one is listening. Although, in principle, I agree with the Moscow journalist Latynina, who said that the American government, in fact, has nothing much to be ashamed of. Because in their dispatches, they did not say anything radically different from what they say publicly. They might have spoken in a different language. Just as we, say, speak among ourselves with certain words, but when speaking publicly, we choose our words more carefully. It’s a different matter for authoritarian governments, which say one thing publicly but in reality mean something completely different.

Yevhen Hvozdetskyi, physics student: I would like to ask how you feel about contemporary Ukrainian nationalism—for example, the “Svoboda” association? Is it, in your opinion, a nationalism of love, or a nationalism of hatred and enmity?

Marynovych: Thank you, also a very interesting and important question, it seems to me. I think that in “Svoboda” there are many young people with restless, not indifferent hearts, who are looking for answers and do not want to accept complicated and multi-layered explanations. Their youthful hearts demand a clear and short answer. I must tell you that when I was young, I also did not want those complex explanations. I wanted a very clear answer… Is their nationalism based on love, or on hatred? I think that the situation is different in different regions of Ukraine. In Lviv, I witnessed how steeply the politics of the local “Svoboda” members are mixed with xenophobia and antisemitism. I myself went with representatives of our local Jewish community to the prosecutor when they were dragged to court on a claim from “Svoboda.” But, say, in Kharkiv, the local “Svoboda” is completely different. There are completely different people there, a different political situation. In Lviv, they, to some extent, let’s say, get brazen, sometimes allowing themselves unacceptable reactions. In other places, members of the same party may have different motives. I would not want to generalize, but I believe that the “Svoboda” party has a big problem in how to get rid of its simplistic formulas.

Member of the Serhiy Podolynsky Society: Please tell us about the events that took place at your university for the anniversary of Mykola Rudenko.

Marynovych: Thank you for this question. Actually, they are still ongoing. We have already had three Rudenko Readings: “The Life Monad of Mykola Rudenko,” “The Physiocratic Monad of Mykola Rudenko,” and “The Poetic Monad of Mykola Rudenko.” Tomorrow at our university, the Ukrainian Catholic University, there will be a concluding, solemn academy in memory of Mykola Rudenko with the participation of Mrs. Raisa Rudenko. Anyone who will be in Lviv, please come.

Dolgin: Thank you. The dissident movement is a heroic page in our Ukrainian social history, the history of Eastern Europe, the history of the former Soviet Union. And now it seems to me that the knowledge of this history, the training from this history, can help us in the present and in the future. Thank you.

Marynovych: Thank you all.

(Applause)

Marynovych: Thank you very much.

Dolgin: We remind you that we gather here every Wednesday. Next time we will have Yevhenia Karpilovska, a computational linguist.

Kadenko: The topic of her lecture is: “Ukrainian Computational Linguistics Today.” Mrs. Karpilovska is a Doctor of Philological Sciences, a professor. Please come, and thank you for being with us.