(Finalized on September 30, 2019, on the eve of the 60th anniversary of his arrest on 1.10.1959)

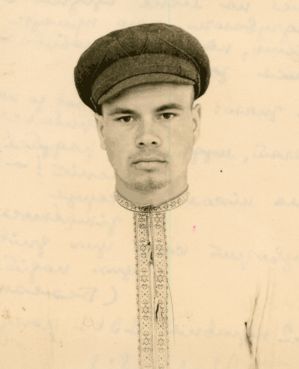

Oleksa Riznykiv (pseudonym—Oleksa Riznychenko) was a member of the “Sixtiers” generation (or rather, the “Fiftiers,” since he was arrested on October 1, 1959, for a leaflet from 1958), a member of the Writers' Union of Ukraine, and the author of two dozen books of poetry and prose—"Ozon" (Ozone), "Ternovyi Vohon" (Thorn Fire), "Naodyntsi z Bohom" (Alone with God), "Odnorymky. Slovnyk omonimiv" (Monorhymes. A Dictionary of Homonyms), 2002, "Skladivnytsia ukrainskoi movy. 9620 skladiv nashoi movy" (A Storeroom of the Ukrainian Language. 9620 Syllables of Our Language), 2003, "Illeiko, z Boha tureiko" (Illeiko, from God a tureiko), the mystery play "Bran" (Captivity), "Spadshchyna tysiacholit. Chym ukrainska mova bahatsha za inshi?" (The Heritage of Millennia. How is the Ukrainian Language Richer Than Others?) (5 editions), "Maiunella" (written in 1969, restored on February 20, 2014), "Slovohrona Dukhu. Novyi korenevyi slovnyk" (Word-Clusters of the Spirit. A New Root Dictionary), 2015, "UkraMars" and others.

He is a laureate of literary awards named after Pavlo Tychyna (1995), Konstantin Paustovsky, Taras Melnychuk, Stepan Oliynyk, Borys Hrinchenko, Yaroslav Doroshenko, Todos Osmachka, Leonid Cherevatenko, Yuriy Horlis-Horsky, and Yevhen Malaniuk (2019).

He was repressed twice in Odesa by the KGB—in 1959 and in 1971. He was sentenced to a year and a half the first time, and five and a half the second. Here is his story of the first repression, which occurred 60 years ago—on October 1, 1959.

Many, many people saw that the king was naked. And everyone understood that you couldn’t say it out loud—you would pay for it with your freedom or even your life. Only great lovers of truth or children, like the boy in Andersen’s fairy tale “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” dared to say it. Children, as a rule, are not yet aware of the danger they face, or if they are, the natural pull towards Truth in their souls outweighs any fear, and they manage to shout, before fear can take hold:

“But the emperor is naked!”

Then the commotion would begin.

Some would quickly avert their eyes, lest someone notice that they, too, see the king’s nakedness; others would look around, wondering if anyone else had noticed that they see it too...

The weavers, who had made a fool of the king and the entire nation by claiming that only intelligent people could see the New Fabric, were the most frightened. These illusionists, or more precisely, these “materialists,” knew perfectly well that the Fabric did not really exist, but they counted on the power of the Word: “call a man a pig a hundred times and he’ll start to oink,” “say halva a hundred times and your mouth will become sweet.”

And so these “materialists” use the same trick, they start shouting: “Catch the liar!” just as a thief, while running away, pretends to be the one chasing the thief, yelling, “Catch him!!”

Who will the people follow, whom will they hear? And the king? Will he be ashamed of his nakedness? Or will he have to continue pretending that he believes he is clothed?

61 years ago, I was one of those boys who cried out, “But the king is naked!” Although no, we didn’t cry out, but secretly wrote about it in a leaflet and distributed this news throughout Kirovohrad and Odesa at night, stealthily. Many more years would pass before we and others understood that this should not be done in secret, not stealthily, but spoken aloud, as academician Sakharov, Ivan Dziuba, also now an academician, Mykola Rudenko, Sviatoslav Karavansky, and Viacheslav Chornovil later did.

But back then, in the summer of 1958, raised by the school system, we both spoke in hushed tones and wrote that leaflet conspiratorially, so that no outsider would know or hear about it, about our intentions, even about our thoughts!

In the city of Pervomaisk, Mykolaiv Oblast, where my parents had moved from Donbas, from Yenakiieve, back in 1948 to escape the famine, there was a group of youths united by a passion for writing poetry. A literary studio had existed there since 1951, and we attended it while still in school—Mykola Vinhranovsky, Vitaliy Kolodiy, Stanislav Pavlovsky, Andriy Yarmulsky, Isaak Savransky, Stanislav Shvets, and my humble self. The local newspaper published my first poem on May 5, 1952. We performed in schools and on the radio, getting used to the word “poet.”

In 1958, I graduated from the Odesa State Theater, Art, and Technical College and was assigned to the Kirovohrad Ukrainian Music and Drama Theater named after Kropyvnytsky. I started working there in the spring as a lighting technician. I lived in a dormitory with two rooms. Every evening, and sometimes during the day, wonderful Ukrainian plays were staged, which I knew almost by heart from my practicum at the Odesa theaters. In the library, I read *An Introduction to Indian Philosophy* and *My Life* by Mahatma Gandhi, and wrote poems, mostly in Russian, though I was surprised that some actors spoke Russian in their private lives.

I often visited my parents on weekends. They lived in the third part of the city of Pervomaisk, in a unique place called Bohopil, a triangle between two merging rivers, the Boh and the Syniukha. My former literary studio colleagues had scattered—Mykola Vinhranovsky was taken to Moscow by Oleksandr Dovzhenko himself, to VGIK for the directing faculty; Andriy Yarmulsky and Vitaliy Kolodiy went to Odesa; Stanislav Pavlovsky to Kyiv. My God, none of them are left on this sinful Earth!!

When I visited my parents, I met with my literary circle colleagues—Volodia Barsukivsky, Ivan Halyniak, Stanislav Shvets, Valentyna Kravchuk, and others.

Remember what time it was. Nikita Khrushchev had just exposed the terrible mechanism of the cult of personality, shedding light on the means and methods of destroying people; “allied,” meaning imperial, troops had recently been sent to Hungary. A new wine was fermenting and bubbling throughout the vast empire. We, drunk on its fumes, were somehow certain that groups like ours existed in every city and town. Just as we talked “about politics”—so did they. Just as we disliked the dictatorial “party”—so did they. Just as we wrote a leaflet—so did they. Yes, yes, we decided to fight the dictatorship of the Communist Party with the only means available to us—leaflets.

We wrote it on the banks of the Boh and Syniukha rivers so we could see from afar if anyone was approaching. We sewed the thin sheet of paper into the cuff of our trousers, and we invented and agreed on secret words to use in letters about our cause. And although in the end only Volodymyr Barsukivsky and I were left, we still signed the leaflet “SOBOZON,” which was meant to stand for “Soyuz Borby za Osvobozhdenie Naroda” (Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the People).

The two of us printed it in the office of the Pervomaisk food processing plant where Volodia Barsukivsky worked. We made stacks of 9-10 thin sheets of paper with carbon paper. So by the day of distribution, we had up to 30 leaflets. We decided to distribute them in Odesa, where Volodia was going to visit his mother for the so-called October holidays, and in Kirovohrad, where I worked.

We had to distribute the leaflet only on the approaching “October holidays” to make the blow against the communists, who had essentially become a new exploiting class, an exploiter of the people, more stinging. It was to them that I dedicated a poem at the time, written in the style of Mayakovsky, who was then my favorite poet.

ВАМ!

Вам, не знающим с жира делать что,

Тратящим тысячи на пустяки,

Как вам не стыдно отделываться мелочью,

Брошенной в ладонь народной руки!?

О ней толпы крика гуляют везде,

Лезут в глаза, в уши и в рот,

А шепотку о том, что вами народ раздет,

Не откроют даже ворот!

Excerpts from the “Resolution on the Re-Presentation of Charges” dated December 30, 1959, compiled by Senior Investigator Rozhko.

“On July 20 of the same year, 1958, Barsukovsky came to the accused Reznikov in the city of Kirovohrad to compose an anti-Soviet leaflet, bringing with him on a sheet of paper certain political expressions and words to be included in the text of the anti-Soviet leaflet. There, in the city of Kirovohrad, on July 21, 1958, Reznikov and Barsukovsky composed a draft of an anti-Soviet leaflet and rewrote it by hand in two copies, and also agreed to multiply it on Shvets's typewriter.

Before leaving Kirovohrad, for conspiratorial purposes, at Reznikov’s suggestion, Barsukovsky exchanged handwritten texts of the anti-Soviet leaflet with him and sewed it into the cuff of his trousers...

At the end of July or beginning of August 1958, Barsukovsky lost the anti-Soviet leaflet he had, and therefore decided to travel to Reznikov in Kirovohrad again to write another leaflet.

On August 10, 1958, the accused Barsukovsky came to Reznikov for a second time and brought with him a text of the lost leaflet that he had written by hand from memory. Reznikov, together with Barsukovsky, using the copy of the anti-Soviet leaflet kept by Reznikov, handwrote 2 copies of the leaflet, making some changes and additions to its text. At that time, they again discussed plans for acquiring printing type, and methods and places for distributing these leaflets...”

And here is another quote from the same Resolution on the Re-Presentation of Charges.

“While in the city of Kirovohrad, Reznikov, on the day of November 7, 1958, dropped one anti-Soviet leaflet into a mailbox on K. Marx St., building № 56, and on the evening of the same day, gave five such leaflets to V.V.K. for distribution, telling V. that if he distributed the leaflets, he would be considered a member of 'SOBOZON.' After that, on the same evening, Reznikov placed one anti-Soviet leaflet on the entrance gate of the construction technical school in Teatralny Lane, № 3, placed one on the iron fence of building № 4 on Dekabristov St., one behind the sign on the entrance door of Pharmacy № 4 on Volodarsky St., 56, one on the iron gate of building № 97/59 or № 93 on Hohol St., that is, he personally distributed five anti-Soviet leaflets throughout the city, about which he reported in a veiled form in a letter to Barsukovsky in December 1958.”

Such actions, such propaganda.

On November 9, 1958, I am drafted into the navy, taken to Sevastopol, and I study for a year at a radiometry school.

In the summer, at the behest of the KGB, which had already stumbled upon the trail of SOBOZON, I was sent to Odesa and placed at the 16th station of Velykyi Fontan, where the coastal post for signaling and monitoring the entrance to the port was located at the time, and I served there for several months, where they observed and signaled about me. That summer, Volodia Barsukivsky returned to Odesa after working for two years in Pervomaisk after his technical college. They brought us together to continue their surveillance. And on the first day of October 1959, they searched my “bunk,” Volodia’s place, my parents’ home in Pervomaisk, and Shvets’s place...

But it seems to me it’s time to get acquainted with that leaflet, which the investigative bodies constantly called anti-Soviet. As you read it, count how many times we spoke out against the SOVIETS, anti-SOVIETS:

APPEAL TO THE PEOPLE

DEAR FRIENDS AND COMRADES!

People who have found in themselves the strength and courage to oppose the hateful dictatorial policy of the party and the current rulers are appealing to your minds and hearts.

FRIENDS!

Look at the world with clear eyes, cast off the veil of deceitful words with which the handful of communists who have seized power entangle you with the help of newspapers and radio.

Do you not smile ironically when reading newspapers or listening to the radio, are you not outraged by the vile lies and duplicity that permeate every phrase, every speech?

They shout about freedom and democracy, but this is freedom in a cage, and the power of the people has been stifled and replaced by the power of the party’s elite.

They shout about the wealth of the people, about the rise in their well-being, but the people, meanwhile, are poorer than before the revolution.

A worker cannot feed himself on his meager salary, let alone a family.

And how does a peasant live? The land, watered by the sweat of their grandfathers and fathers, was taken from him. Driven into a kolkhoz, having no interest, no attachment to the land, he goes to the city to escape the rural misery.

But what will he find there?

The same lack of rights, poverty, and a downtrodden existence. A shortage of food, footwear, and clothing, high prices and meager earnings—these are all the achievements of over forty years, during which the people have seen nothing but wars, ruin, famine, tyranny, and deceit.

The foolish and dictatorial policy of the Communist Party, both within and outside the state, leads the world to a schism, to an unbridled arms race with the expenditure of countless national resources, and brings confusion and fear for their future into the hearts of people.

FRIENDS AND COMRADES!

We want brotherhood, true brotherhood, not enmity between the peoples of all countries of the world!

Enough of splitting the world into two so-called “camps”!

Down with the fascist dictatorship of the party!

We need genuine freedom of opinion, speech, and press!

We stand for the recognition of religion and the church by the state!

Down with atheistic propaganda!

Long live the genuine freedom of the people!

Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the People (SOBOZON)

Well? How many times did we mention the Soviets? Not once?

That’s the point: the leaflet is entirely anti-party, not anti-Soviet. And this is not surprising—we knew even then that the real power belonged to the party, and the Soviets were just for show, to create the appearance of popular rule. And on the other hand, there were Soviets in Kyivan Rus, among the Cossacks, and there was the Central Rada during the years of the liberation struggle. Therefore, the KGB investigative bodies deliberately distorted the facts, of course, with the knowledge of that very same party, which had appropriated, brutally usurped power from the Soviets, but stubbornly called that power Soviet. As Mayakovsky wrote, “we say one thing, but mean another...”

EXCERPT FROM THE INTERROGATION PROTOCOL OF OCTOBER 1, 1959

Interrogated by Lieutenant Colonel MENUSHKIN, head of the special department of the KGB, military unit 42860.

QUESTION: Among the documents and notes seized from You during the search today, there is a poem entitled “TO YOU.” Tell us what motives prompted You to write this poem and what You wanted to express with it?

ANSWER: Indeed, among the various notes seized from me today during the search, there is a poem I typed in 1957 titled “TO YOU.” The latter is an attempt to imitate Mayakovsky, who in the recent past was one of my favorite poets, and I was fond of his early works. As can be seen from the text of this poem, I tried to express in it the idea of the social inequality that exists in the Soviet Union, or more precisely, the wealth inequality between different segments of the population.

QUESTION: What segments of the population did You have in mind in this poem, in particular, who did you mean by the “stripped-bare people” and the people “shouting about happiness, while secretly drinking their lifeblood?”

ANSWER: By the expressions used in my poem “TO YOU”: “...that the people are stripped bare by you,” “...how can you, who shout about happiness, while secretly drinking their lifeblood...” I meant people receiving a low salary of up to 400 rubles, and, on the other hand, the population receiving a salary of 2000-3000 rubles and more.

QUESTION: Your answer is incomprehensible and illogical, considering that salaries of 2000-3000 rubles are received by qualified workers and a significant number of people engaged in mental and physical labor for the benefit of the Soviet people?

ANSWER; I believe that people with low salaries also need to be clothed and fed. In addition, to the second category of people who strip the people bare, shout about their happiness, while secretly drinking their lifeblood, I include speculators and bribe-takers.

QUESTION: In the notes seized from you during the search, one of the notebooks contains a story dated 16.7.58 and entitled “But It’s Good Nevertheless! (a letter to the newspaper).” Who does it belong to and who wrote it?

ANSWER: The aforementioned story “But It’s Good Nevertheless! (a letter to the newspaper)” was written by me and belongs to me.

QUESTION: What prompted you to write this story?

ANSWER: I was prompted to write this story by everything that is written there. It seemed to me that everything stated in this parodic “letter” corresponded to reality.

QUESTION: Don't you find that your, if I may say so, “work” is of a libelous nature, namely: in your story “But It’s Good Nevertheless!” you try to elevate individual moments to a degree, to generalize them, and thus to discredit the economic situation of the Soviet people and the measures being taken by the party and our government to raise their standard of living?

ANSWER: No, I don't. With my story “But It’s Good Nevertheless!” I wanted to say that one should see not only the good, but also the bad, and shout about it in order to eradicate this bad more quickly...

Note the calm tone of the conversation, that capital “Y” in addressing me: You; my light humor: “I was prompted... by everything that is written there...”

Well, this is the first day of the arrest. The first interrogation. The first clash with the cold, soulless machine of the Empire.

Here they are interrogating my fellow student from the radiometry school, Volodia Moklyak.

“Reznikov stated that there is injustice in our life (i.e., in the USSR), as there are large differences in salary sizes. He said that in America, workers are allegedly better off than in the Soviet Union. In support of this, he stated that in America there is one car for every three workers, while here cars are few and expensive. This conversation between us took place in May 1959 in the academic building during a break. From this conversation, I concluded that Reznikov shows dissatisfaction with the structure of life in the USSR...”

A terrible crime, Mr. Menushkin!

On December 13, 1959, he is interrogated again, and the first question is:

“At the interrogation on October 22, 1959, you testified that Reznikov made politically harmful statements in your presence. Specify how those present reacted to such statements by Reznikov.”

ANSWER: On October 22, 1959, I basically told everything. In addition, I remembered that Reznikov, among his colleagues at the radio technical school, expressed dissatisfaction with the removal of Marshal Zhukov from his post; in particular, he stated that Zhukov had great merits and was removed from his post while he was in Yugoslavia. Reznikov considered this treachery and said that Zhukov was allegedly feared, which is why he was treated that way.

Well, this is even more horrifying!!

And here is the testimony of Valentin Vendelovsky, at the time of the interrogation, the head of the secret (!!?—know our own!) department:

QUESTION: On what specific issues and in what way did his opinions on political issues prove to be incorrect (??—O.R.)?

ANSWER: Around May 27, 1959, the question of concluding a peace treaty with Germany and turning West Berlin into a free city was very widely discussed in our press. In connection with this, Reznikov, at about the same time, approached me, in the company of other people, with the question: ‘Why does the Soviet Union object to holding ‘free’ elections in Germany?’

I gave him an explanation corresponding to the position of our Soviet government. Disagreeing with me, Reznikov stated that this was not democratic. Reznikov did not express his opinions on this matter more sharply in conversations with me, although Reznikov approached me with such a question several times and told me that I was not expressing my own opinions, but the opinions of the Soviet press. From this, I conclude that Reznikov had different opinions on this matter...

Reznikov was wrong in his assessment of Mayakovsky’s work, the poetry of which, criticizing the shortcomings of our movement in the first years of the Soviet state, Reznikov automatically transferred to a later and even contemporary period of our development, although Reznikov admired Mayakovsky’s work...

How do you like that convolutedness?! “the poetry of which... he transferred to a later period...”? My God, my God, what a period we lived through! Think about these questions and answers, immerse yourself in that primitive, idiotic atmosphere that surrounded us, which we breathed, beyond which we could not, had no right to escape! “Do not dare to have your own opinion!” Let alone—to express it! And how much freer, more uninhibited, bolder, and wiser we are now!...

Here is page 62 of the first volume of the case. Anatoliy Zaichenko, my classmate from the radiometry school, is responding, being interrogated, of course, during the days of my arrest.

“Reznikov, for example, expressed that, allegedly, here in the USSR it is very difficult to acquire a necessary item, while in capitalist countries it is easy to do so. Reznikov especially argued about the purchase of passenger cars and consumer goods. On this issue, many argued with Reznikov and proved to him the incorrectness of his views.”

Huh? How about that? *“Read and envy—I am a citizen of the Soviet Union!”* said Mayakovsky. But let’s read on, let’s read on!

“Sailor Volodymyr Moklyak very often criticized Reznikov, who, regarding the opinions expressed by Reznikov, directly told him: ‘You’re a Komsomol member, yet you talk nonsense.’”

Reznikov tried to prove among the personnel that here in the USSR, allegedly, there is very low pay for labor in the kolkhozes. Even I personally tried to refute Reznikov's incorrect opinions on this issue.”

In the summer of 1958, while working at the theater, I lived in a small room that served as the theater's dormitory—there were three of us. Here, Volodymyr Kubyshkin, a novice actor, a choir member, tall and a bit clumsy, is being interrogated:

“I didn’t like these poems, as their content was decadent, pessimistic, and one could feel an admiration for Yesenin... I remember a fact. Soon after Reznikov started working, I was reading the book ‘The Blue Arrow.’ Reznikov asked me what I found good in it. I said: that it’s about the deployment of spies. Reznikov, having heard this, stated that it was nonsense, why was I interested in it, they weren’t bothering me. I again objected to Reznikov, that it’s not about personal matters and personal interests, but about undermining our economy and the might of the social order. We argued a lot in this debate, but Reznikov stuck to his opinions. From that time on, Reznikov never started conversations with me concerning our Soviet reality, and we even stopped walking to work together.”

Yes, yes, he told the truth. It just became uninteresting for me to talk to him. And they called him a “blockhead” at the theater anyway.

They are interrogating the theater artist Viktor Sochenko.

QUESTION: How can you characterize Reznikov in political terms?

ANSWER: It's difficult for me to do so—I hardly knew him. I read his poems. One story about some beggar or a blind man. I don't remember the content, the impression was not good, as everything in the story is described in dark colors. I told Reznikov that one could only write like that about the life of old tsarist Russia. He was fond of Yesenin's poems, some he recited by heart... Reznikov was not well-off financially, and this often manifested in his decadent moods. He told me that it was hard for him to make ends meet, and in this respect, he was dissatisfied with his situation.

I remember that Reznikov was fond of abstract art, loved to look at illustrations by abstract artists in the magazine "Poland," admired them, and argued that this painting needed to be understood.

QUESTION: Under what circumstances and in connection with what did Reznikov, while talking with you, slander Soviet reality, the policy conducted by the Communist Party and the Soviet government?

ANSWER: I did not hear any openly anti-Soviet statements from Reznikov. I cannot recall him consciously slandering our reality, the Communist Party, or the Soviet government...

Compare the question and the answer. The question itself hammers into the witness’s consciousness the idea: Riznykiv is an “anti-Soviet.” But Sochenko was, apparently, a tough nut to crack.. Unfortunately, I barely knew him...

Volodia Barsukovsky’s noosphere was investigated in the same way, his “decadent and pessimistic poems.” Volodia analyzed the reasons for the emergence of such moods and intentions in us very accurately:

“... We read our poems to each other (I and Reznikov), found much in common in what was expressed. At work, I saw and came into contact with life, so to speak, up close, I saw duplicity, bureaucracy, and this struck my consciousness, accustomed to seeing something romantic and sublime in everything; in books, moreover, for some reason I only saw the good, while in life, on the contrary, I saw only a lot of negative. I struggled with myself, searched agonizingly for a way out and could not find one.

Several times I touched upon our life with Reznikov, and for some reason, we found that it was arranged poorly. How to arrange it better?—we, romantically inclined, dreamed and asked ourselves.”

Huh? What a wonderful analysis, what an insight into our youthful psychology!

But here I come to the main thing that happened to me in the cell. On October 16, in the newspaper *Pravda*, which they pushed through the “feeder” slot every day, I read that Stepan Bandera had died in Munich on 15.10.1959, that is, the day before. Two or three hours later, the investigator, looking piercingly into my eyes, told me the same thing. I, intuitively sensing some insidious trap, believe I asked him who that was? Although I knew something about the struggle of the UPA, because there was a demobilized guy in the college who had been serving in the Soviet-occupied territory of Western Ukraine and would tell stories over a drink…

This—deliberately simple-minded—reaction of mine to this news, plus my writings in Russian, and my letters to my parents in Russian (“Hello, dear Papa and Mama... Your son Alexei”), led to the investigators no longer speaking with me on Ukrainian topics.

And I—suddenly—in my cell!—on my own—come to the truth!!

It happened like this. I am lying on my bunk and reading Ilya Ehrenburg’s little book *Years, People, Life*. And I come across a story about how the author is crossing the border from France to Belgium. And he casually mentions that the language in Belgium is French. This strikes some chord in me. I reread it again. The thought logically follows—then why does Belgium exist independently from France?? If the language is the same, there should be one state!!

And then my thought jumps to our country. Why are we in the same state with Russia? We have different languages!! In school, I studied Ukrainian and Russian! Two languages! Different ones!! That means we should be separate states!!

Can you imagine what suddenly began in my soul? I am still amazed by the emotional intensity with which I made my discovery. I was running around the cell, tearing my hair out!! My heart was pounding! How could it be that I was so ignorant!? I am 20 years old, and I don't know that Ukraine is in bondage! But it must be a sovereign, independent state!! Why do I know the first two volumes of Mayakovsky by heart, but not Taras Shevchenko, not Lesya Ukrainka, not Ivan Franko!? They are my poets! I am a Ukrainian!!! Why did I write Your son Alexei?? I am a Ukrainian, so I am Oleksa!! Why am I *Reznikov*? I should be Riznykiv, or Riznychenko!! And in general—how could I have forgotten about my people?

And this raged in my soul for several days. I made a promise to myself to apply to study Ukrainian philology, if they didn't shoot me or give me 10-15 years.

Later, in the mystery play “BRAN,” I described this with these words:

Я в еміграції духовній

у юності перебував.

Був яничаром майже повним,

і власну мову забував!

Якраз тоді душа Степана,

осиротівши в чужині,

шукала душу безталанну,

щоб знак життя черкнуть на ній.

І я цей знак прийняв, як хлосту!

Він душу юну роз’ятрив –

і яничарство, мов короста,

опало з мене – я прозрів!

Побачив раптом Україну,

дітьми́ забуту, в кайданáх!

До неї,

ставши на коліна,

заговорив словами сина,

благав: прости мене, страдна!...

Meanwhile, the investigation continued its course. To this day, I am grateful to God that I had the sense not to tell anyone about my discovery! Not even that plant who was in the cell! And that saved me. Because if the investigators had found out about my sudden Ukrainophilia, I would have gotten 7 years! I learned about this possible outcome already in the camp, where captive UPA soldiers explained our short sentence—a year and a half each—to Volodia and me.

Volodymyr and I, almost sincerely, told almost everything, repented, trying not to involve others. We were tried by a military tribunal of the Odesa Military District, as I was a navy sailor.

By the day of the trial, both I and Volodia, with whom we were brought together on January 1, 1960, had found a common language regarding Ukraine, because he, although an Odesan, spoke Ukrainian with his mother, just as I did with my parents.

We became nationally conscious people, understood that, in the words of V. Vysotsky, “everything the poet wrote was nonsense.” And we renounced the past “nonsense,” we decided to dedicate ourselves to Ukraine, to its liberation from colonial dependence. And so, when on February 19, Judge Gorbachev offered me to give a final statement, I firmly promised to create, to build a second life, reciting a poem written on the night before the final day of the court proceedings (the trial lasted from February 15 to 19, 1960).

Я долго думал.

Дни и ночи.

И как машину в мастерской,

своєю собственной рукой

я жизнь свою не между прочим,

а специально разобрал,

и каждый день, как винтик малый,

и каждый месяц, словно вал,

я со вниманьем небывалым

пересмотрел и перебрал.

О сколько грязи, сколько пыли…

Когда, откуда, почему

детали эти запылились —

я не пойму!

Нет, не пойму.

Я все прочистил, все я смазал

суда, раскаянья слезой,

пересмотрел душевным глазом —

и вот они передо мной:

из тех же мускулов и кожи,

из тех же глаз,

из тех же рук —

другую жизнь собрать я должен

и я клянусь,

что соберу!

Judge Gorbachev practically applauded me and gave us a year and a half each in a strict-regime camp, even though the prosecutor had asked for four for me, and three for Volodia. The prosecutor even filed an appeal, but the Supreme Court upheld our sentence of one and a half years each.

On the way to Mordovia, we sang Ukrainian songs, intensively mastered our spoken, half-forgotten native language, and wrote poems and letters home already—in Ukrainian. And I also composed a poem in the Stolypin car, filled with apologies to Ukraine:

Жевріють на обрії зорі,

і місяць, самотній юнак,

когось вигляда на просторі,

але не знаходить ніяк.

Мовчать тополеві алеї,

схилилися верби сумні,

верхів’ям своїм над землею

вклоняючись низько мені.

Прости, дорога Україно,

я вперше лишаю тебе.

незвідана доля закине

мене за Уральський хребет.

Чарівнії ночі духм’яні,

як довго не бачити вас?

Як довго в важкому чеканні

Вбирати в багаття прикрас?

Як довго надією душу,

жалем і тугою палить?!

Я вірність тобі не порушу.

та серце щось дуже щемить…

Про тебе там хто нагадає,

чарівна веснянко моя?

Лиш місяць, що зараз сіяє,

і там буду бачити я.

In the Mordovian camp, they placed us in overcrowded barracks, all the way up on the third tier.

So we met the Green Holidays amidst the festive greenery with which the UPA soldiers had decorated the barracks. And I wrote this poem:

Лапате листя клена

схилилося до мене.

Я кленом цим зеленим

вквітчав свою постіль.

В цей тихий вечір синій

я знов до тебе лину,

далека Україно,

і знов молю: "Прости!

Прости, моя кохана,

страднице безталанна,

навіки нездоланна,

дорожча за життя,

що я не знав про тебе,

що я не чув про тебе,

не бачив те, що треба,

за купою сміття.

Тепер я бачу, ненько,

твої хати біленькі,

твої річки бистренькі,

степи твої й поля,

козацькії жупани,

сміливі отамани,

твої відкриті рани,

страдалице моя...

А я співав про квіти,

про сум душі своєї

і мову, рідну мову

вже починав втрачать,

Дозволь же над тобою,

Над долею твоєю

оновленому серцю,

коханая, ридать".

But should one really weep? Or is something else necessary?

Such questions, laughing and somewhat mocking me, my new comrades in captivity—former soldiers of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, of whom there were over a thousand in the camp—began to ask me! Healthy, strong, handsome men, taken prisoner while wounded, they did not lose heart, even though they had the maximum sentences—25 years!

In the camp, 80-90 percent of the population were Ukrainians. It seemed that the main enemy of the empire was us. The UPA soldiers were predominant; they had sentences of 10-15-25 years. All of them had been taken prisoner while wounded, treated, sometimes for a very long time! And then they were tried and... given the death penalty. After several terrifying months of waiting for execution, their sentence was changed to 25 years of hard labor...

It's horrifying, but many thousands were shot, but these men I met in the camps of Mordovia had already served 8-10-13-15 years. They rejoiced at the Khrushchev Thaw, which seemed like paradise after the terrible years of Stalin's torture. Moreover, that summer, a people's court was in session in the camp, and it retried cases daily, because by then a new Criminal Code had been issued, where the longest sentence was 15 years instead of the former 25. So the court released 25-30 people every day, with the wording "for time served." By September, we had already moved down to the first tier of bunks.

Somehow, these men took us young ones under their wing, giving us the right books to read, telling us about their "criminal cases," teaching us the language, the history of Ukraine, especially the history of the liberation struggles, and patriotic songs. And, of course, the Ukrainian anthem—"Shche ne vmerla Ukraina" (Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished). From them, I learned about the trident, the blue-and-yellow flag, the extraordinary history of "Prosvita," about the "Sich" societies that existed in every village, about Symon Petliura and Yevhen Konovalets…

I understood that their companies, platoons, and squads were a direct continuation of the Cossack sotnias and armies... Yes, this was truly our army, which clearly knew that it was fighting for Ukraine!

They often told stories about battles with the fascists and KGB agents. But more often about how they were persecuted and exterminated by the fascists. The boys convinced me that they did not collaborate with the occupiers, because Soviet propaganda vilely and insidiously, constantly accused them of this. And I myself understood the truth when I saw the contempt, disdain, and disgust with which the UPA members treated the few former policemen, who even here, in the camp, subserviently collaborated with the administration, which was considered shameful for all of us.

That is why, even back then, I recognized the UPA as a belligerent side in the Second World War and perceived them as heroes of a just war of liberation, equal to the Cossacks of Khmelnytsky and Mazepa.

In the camp, I became friends with Sashko Hryhorenko, also a former military man, like me. He served as far as Azerbaijan, wrote several poems where he mentioned and praised the Hungarians (I recall the words: “Imre Nagy raises the flag!”), and read them in the barracks. The next day he was arrested, tried, and given a full 6 years. So the UPA soldiers explained to us that if we had demanded freedom for the Ukrainian people in our leaflet, and not some abstract people, we would have gotten a sentence like Sashko’s.

But back then, in 1960, the Khrushchev Thaw was still ongoing, and sometime in September 1960, at his mother's request, Sashko's sentence was reduced by three years, which we celebrated boisterously with a cup of tea...

Sashko dedicated this poem to me:

ОЛЕКСІ РІЗНИКОВУ

В краю чужім звела нас доля,

Мабуть, для того, щоби ми

Сказали людям правди голі

Й самі зосталися людьми.

І ми йдемо шляхом чесноти,

Йдемо без гімнів і без од,

Щоб нам не міг очей колоти

За лицемірство наш народ.

У світ письменства, світ строкатий

Ми переступимо поріг

І мусим те удвох сказати,

Чого до нас ніхто не зміг.

Щоб наше серце променисте

До читача могло дійти,

То мушу я творити змісти,

Творити форми мусиш ти.

Слова незвичні, дивні теми,

Не чута досі гострота –

Хай все це з віршу, із поеми

У душі людські заліта.

І як би деякі не злились,

Нам будуть слати і хвали,

Бо, друже, так уже судилось,

Щоб ми поетами були.

Та не забудь, що в дні похмурі

Звела нас доля, щоби ми

Були в своїй літературі,

Крім всього, чесними людьми.

21.VII.61 р.

These words from Sashko were my guidance and command for all these 60 years. Everything I wrote and created was consecrated by his words.

Oleksandr Hryhorenko was a wonderful poet, somewhat resembling Mykola Vinhranovsky in both appearance and talent. In 1962, after his release, he died mysteriously and tragically. But he has not been forgotten: a year ago in the Sicheslav region, his compatriots (with my participation and cooperation) published a wonderful book of his poems and memoirs about him for his anniversary (he was born in 1938)—“Zalizna viddanist vrainskomu narodu” (Iron Devotion to the Ukrainian People) (Dnipro, Zhurfond, 2018, 305 pages).

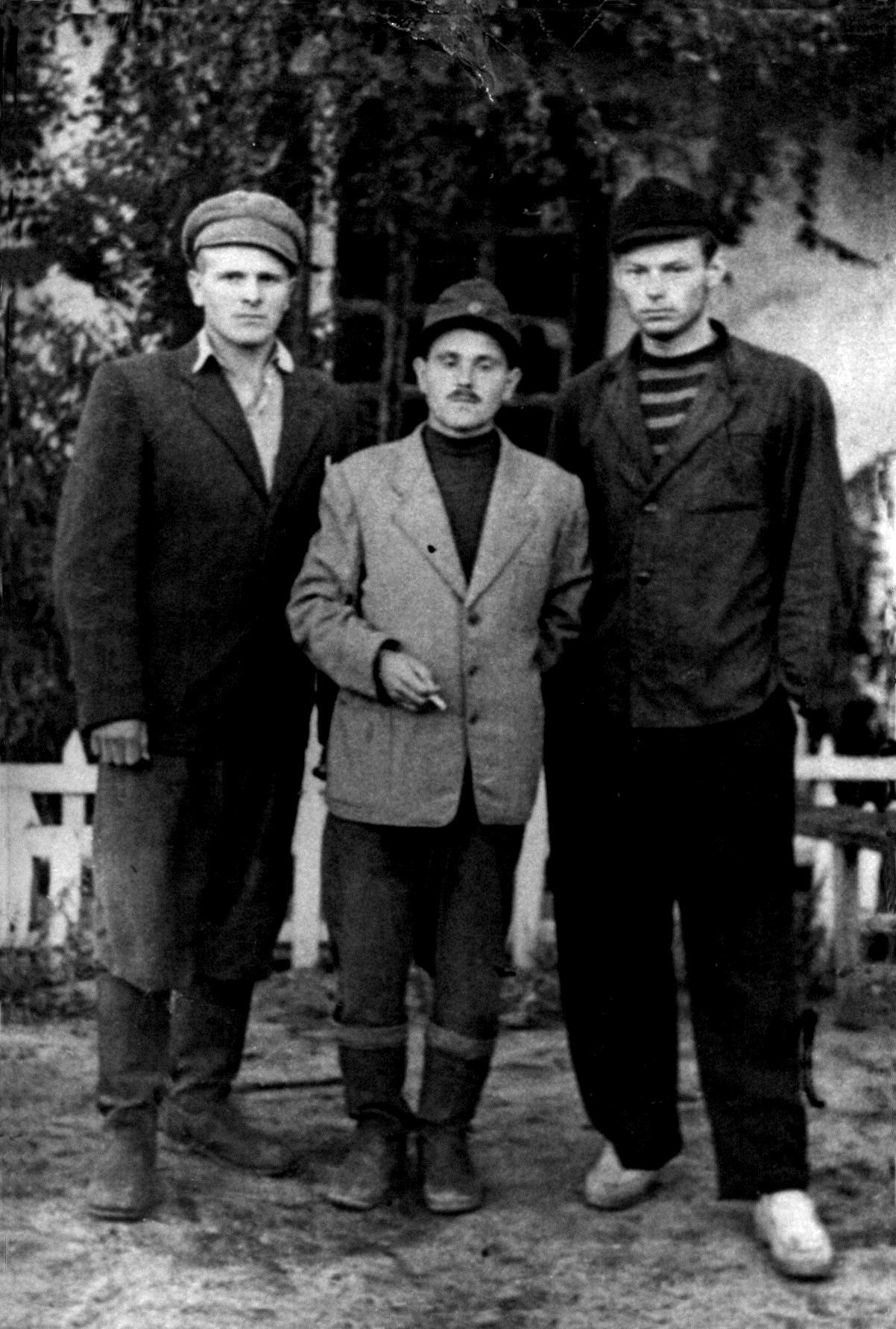

Interestingly, the Khrushchev Thaw extended to the point where a photographer would even come into the zone, take our pictures, and we would pay with cash we had in our pockets!!

Unforgettable for me are those gigantic sing-alongs in the middle of the camp, when 200-300-400 men would sing our folk songs! And the guards would run around shouting “Stop singing nationalistic songs!!” No one paid any attention to them, because the whole community, selflessly, with tears in their eyes, would belt out the words of Shevchenko, these wonderful words of the Cossack captives:

Ой заграй, заграй, буйнесеньке море,

Та й попід тими байдаками,

де пливуть козаки,

тільки мріють шапки

та й по цей бік, та й за нами.

Ой Боже наш Боже, хоч і не за нами,

Неси ти їх з України,

Почуємо славу, козацькую славу,

Почуємо, та й загинем!

It was then that I understood that for them, as for the Cossacks, the main thing was not money, not food, but glory! Glory, Ukraine, and Freedom! They would often, when surrounded by enemies, blow themselves up with the final cry: “Glory to Ukraine!”

I had never encountered such love for Ukraine in the free world, I had never seen such patriots. This worked in unison with my new moods, and my romantic love for Ukraine took on a more real, prosaic meaning, although the romanticism and mysticism, deep piety, and sentimentalism have not faded to this day.

I was released on April 1, 1961. Sashko wrote from the camp that a “frost” was setting in, that they were “tightening the screws.” And the reason for this was the strengthening of the struggle for Ukrainian independence. And for the party, this was “like death.” Here is just one example:

On November 7, 1960, the first organizational meeting of like-minded dissidents took place in Lviv. And on January 21, 1961, Ivan Kandyba, Stepan Virun, Vasyl Lutskiv, Oleksandr Libovych, and Levko Lukianenko were arrested, and later Ivan Kipysh and Yosyp Borovnytsky.

Here the party began to act with all of Stalin’s cruelty: in May 1961, the Lviv Regional Court sentenced Lukianenko to death under Art. 56 Part 1 and 64 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR. The accusation was based on the first draft of the URSS (?) program. He was accused of “harboring the idea of separating the Ukrainian SSR from the USSR since 1957, undermining the authority of the CPSU, and slandering the theory of Marxism-Leninism.” After 72 days, the Supreme Court commuted the death sentence to 15 years of imprisonment. The others received sentences of 10 to 15 years of imprisonment. This was despite the fact that Articles 17 and 125 of the Soviet constitution respectively proclaimed the right of each union republic to secede from the USSR and freedom of speech for every citizen.

I would have the good fortune to meet Levko Lukianenko in concentration camp No. 36 after my second arrest, which occurred again in October, but on the 11th, in 1971, three months before the major arrests of 1972.

But that is another story, which I will tell another time.

Odesa.

Oleksa Riznykiv, writer,

twice repressed by the Soviet Union.

Finalized in September 2019.

Later, I wrote this poem about the journey to the concentration camp:

ДАЛЕКИЙ РІК 60-Й

Мою персону нон грата,

тоді запальну й палку,

трактовано, як гранату,

з якої зірвеш чеку –

і стиснуто межи грати

в чекістському кулаку.

У страсі, у струсі, в стресі

невидимих орд бійці

везли мене із Одеси,

розряджування митці,

в столипінському експресі

на íмперські манівці.

В тайгу, де ще лєший бродить,

де вихолощена мордва,

щоб там розрядить, знешкодить,

а може й – експлодувать.

О, як старались чекісти,

сплітаючи сіть тонку,

у душу, у мозок влізти,

щоб знову вправить чеку,

щоб нашу правду пречисту

ми мали не за таку.

О, як намагався ворог

до нас підібрать ключі,

щоб наш самостійний порох

зволожити, підмочить,

щоб наш ще не Рух, лиш порух

до свóїх команд привчить.

Але не могли ми, вперті,

прийнять від ЧК чеку:

хай ліпше на мить від смерті,

хай в їхньому кулаку –

зате у собі відверті!

Зате не на мотузку!!!

Але як ріки зимові,

убравшись іззовні в лід,

ми крили двигтіння крові

і вільної думки літ,

молились Волі і Слову.

Плекали Свободи плід.

And here is a very charming poem in our language. I was proud of it and still am, because look at when it was written! And it was at the request of Mykola Vinhranovsky. He often reproached me for not writing in our language…

ЖОРЖИНИ

Жоржини, жоржини, жоржини,

Червоні жоржини, мов кров…

Чи знову зустрінемось, сину,

Мій рідний, побачимось знов?

Схилилася бідная мати

На груди синочка свого,

Прим’яла рука кострубатий

Новенький солдатський погон.

Навколо колишеться море

голів і букетів, і сліз…

Який може бути в цім сором,

як біль лише в душу заліз?

Жоржини, жоржини, жоржини,

Червоні букети, мов кров…

Вертайся, вертайся, мій сину,

Вертайся живий і здоров…

І знов зацвітали жоржини,

і знов облітав їхній цвіт…

Вже син підійшов до Берліна,

синок дев’ятнадцяти літ.

І місяць за місяцем тане,

Вже й літо щасливе мина,

А мати неначе в тумані,

Всі ночі проводить без сна.

Нарешті вона, телеграма!

Так значить, - живий і здоров…

І станція знову та сама,

Жоржини, жоржини, мов кров.

Які ж ви червоні, жоржини,

В те літо блідіші були.

Нарешті синочка стежини

Додому, до нас привели…

Колишеться море навколо

Голів і букетів, і сліз.

А хтось не приїде ніколи,

навіки хтось з поїзда зліз.

Жоржини, жоржини, жоржини,

Ви тяжчими стали нараз:

Хтось дуже подібний до сина

З вагону на нас позира.

Невже закінчились хвилини

І сліз, і чекання, і мук?!

…Простягнені сину жоржини

упали під ноги йому.

Стара захиталась, та збоку

чужий хтось підтримав її:

синочок її кароокий

без рук нерухомо стоїть…

ой сину мій, сину мій, сину!

Хоч погляд на рідную кинь!

Жоржини, жоржини, жоржини,

Чому ви червоні такі??!

3.10.1958 р.

Written one month before the leaflet was distributed!!