She was one of the founders and active members of the Clubs of Creative Youth and had a colossal influence on them.

The Horska family moved to Moscow and Leningrad but eventually settled in Kyiv. Alla studied at the art institute, where she met her future husband, Viktor Zaretskyi—a native of Donbas, a Ukrainian who understood very well what it meant to reach for one's own traditions and roots in art.

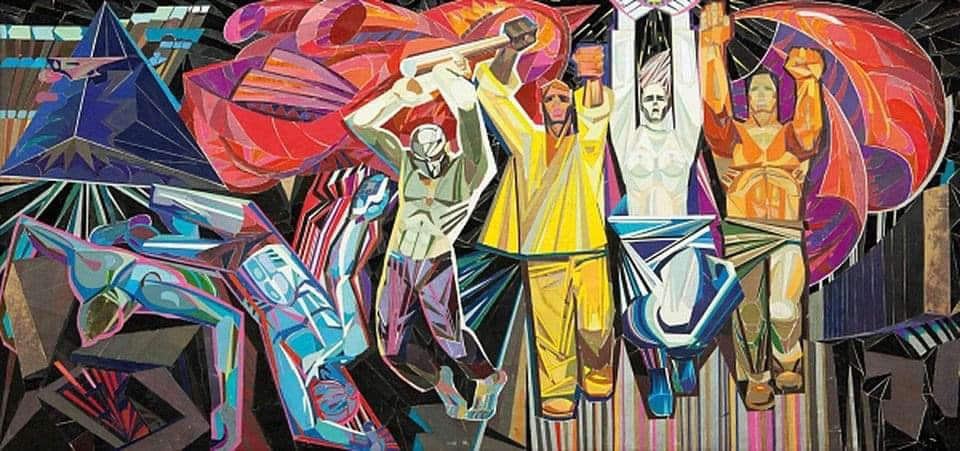

The Donetsk region inspired monumental art. Viktor significantly influenced his beloved's worldview.

In 1961, a life-changing event occurred. With her friend, the Ukrainian philologist Nadiia Svitlychna (sister of Ivan Svitlychnyi and a native of the Luhansk region), she visited the Ivan Honchar ethnographic museum. It was like a concussion, as Alla herself recalled, a return to her roots (as during her studies, Alla had even been exempted from learning the Ukrainian language). There, she saw not only exhibits but also realized Ukraine's purpose, its distinctness as a nation. She realized that she knew neither the history nor the language of her ancestors—all that was materialized in the Ivan Honchar museum—and zealously began to study the language, persistently and consistently reclaiming her own nature.

Another landmark event occurred when Alla Horska, together with Vasyl Symonenko and Les Taniuk, visited Bykivnia, where they suddenly saw children playing soccer with a child's skull that had a bullet hole and was stuffed with hay… They played casually, without a thought. It was then that Symonenko uttered his famous words: “We are all in the cemetery of executed illusions…” Local residents knew the true history of this gruesome place, as they had once seen trucks full of corpses arriving here every night. Moreover—a special tram ran here, transporting the bodies of tortured Ukrainians to the open burial trenches. The shocked young artists wrote a memorandum and appealed to the Kyiv City Council to establish the historical truth and conduct an investigation.

It was during this period that Alla became fascinated with monumental art, which she felt, like her husband, Viktor Zaretskyi, could reflect a national consciousness. And it was precisely this kind of work that the couple created, especially in the Donetsk region.

A legacy, now mostly lost...

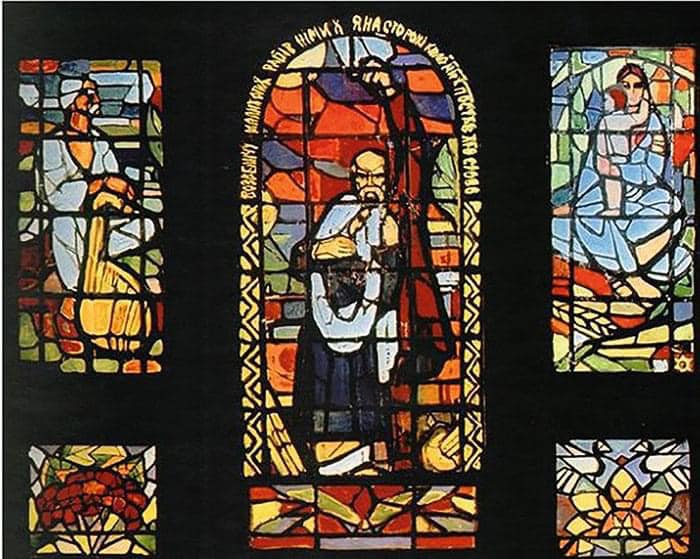

However, the pivotal event in Alla Horska's life, not only as an artist but as a public figure, was not her work in Donbas, but in Kyiv. For the 150th anniversary of Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko, Kyiv University commissioned the Union of Artists to create a stained-glass window with his image. Alla Horska was one of the authors, along with her close associate Opanas Zalyvakha, who suggested adding Shevchenko's quote, “Возвеличу малих отих рабов німих! Я на сторожі коло їх. Поставлю слово. (I will exalt these little dumb servants! I will keep watch over them. I will put in a word.) ” And the Word is knowledge and consciousness—the very thing the Soviet regime feared most. Immediately after a commission's visit to the university, the stained-glass window was destroyed.

A wave of arrests began, targeting those who resolutely declared that the authorities of the time did not allow people to live freely. It was then that Alla Horska became a human rights activist. The trial of Valentyn Moroz, a Ukrainian historian and a unique figure of that era, became a key moment. She attended all the court proceedings in Kyiv and Lviv, and appealed with open letters to the court, the government, and other institutions, demanding, at a minimum, that the trials be conducted according to the law. But the authorities remained deaf.

The decisive moment in her life was the Letter of 139, addressed to Brezhnev, Kosygin, and Podgorny, aimed at defending Ukrainian culture and protesting the terrible repressions that had swept the country. Alla Horska maintained very close contact with exiles and political prisoners. In one of her letters to Opanas Zalyvakha, who was sent into exile after the incident with the stained-glass window, she wrote that it was better to be killed than to endure everything that was happening in the country.

She was heard… On November 29, 1970 (she had disappeared the day before, having not returned home), Alla Horska was found dead with numerous injuries in her father-in-law's cellar in Vasylkiv, and the father-in-law himself was found dead the next day on the railroad tracks. Alla was buried in a closed casket. Her friends present at the funeral—Yevhen Sverstiuk, Vasyl Stus, Ivan Hel, and Oles Serhienko—were arrested shortly thereafter.

It was then that Vasyl Stus dedicated this to her...

"Ярій, душе! Ярій, а не ридай.

У білій стужі серце України.

А ти шукай – червону тінь калини,

На чорних водах – тінь її шукай.

Бо – мало нас. Малесенька щопта.

Лише для молитов і сподівання.

Усім нам смерть судилася зарання,

Бо калинова кров – така густа,

Така крута, як кров у наших жилах.

У сивій завірюсі голосінь

Ці грона болю, що падуть в глибінь,

На нас своїм безсмертям окошились."