The new feature film by Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa, “Two Prosecutors,” included in the competition program of the 78th Cannes Film Festival, became a significant cultural event even at its announcement. As journalist Andrei Arkhangelsky notes, this film, shot in Russian and featuring Russian actors who have spoken out against the Kremlin’s policies, once again reminds the modern viewer of Soviet totalitarianism. However, what gives this event particular depth is the figure of the author of the literary source material—writer and physicist Georgy Demidov, whose own fate is a powerful statement about the nature of oblivion and resistance.

Plot

In a Bryansk prison in 1937, thousands of letters from prisoners who are victims of false accusations are burned. One letter escapes the fire and finds its way to the home of Alexander Kornev, a local prosecutor. Newly appointed to his post, the young lawyer tries desperately to contact the letter’s author. Kornev soon discovers that the prisoner is a victim of corrupt officers of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD). Witnessing these abuses, he travels to Moscow to appeal to the USSR Prosecutor General, Andrey Vyshinsky. However, Kornev’s unquenchable thirst for justice leads to his own demise.

Loznitsa’s goal is to challenge the “boredom of repression”—that cynical attitude cultivated for years by Putin’s propaganda, which presents the Stalinist era as a “great, albeit tragic, time.” The director seeks to restore to the words “Stalinist repressions” their true, chilling horror. To do this, he turns to the uncompromising and brutal prose of Demidov, who, according to critics, rightfully stands alongside Solzhenitsyn and Shalamov. “The time has come to look the Soviet monster directly in the eye. It must be understood in order to be defeated,” Loznitsa says of his film.

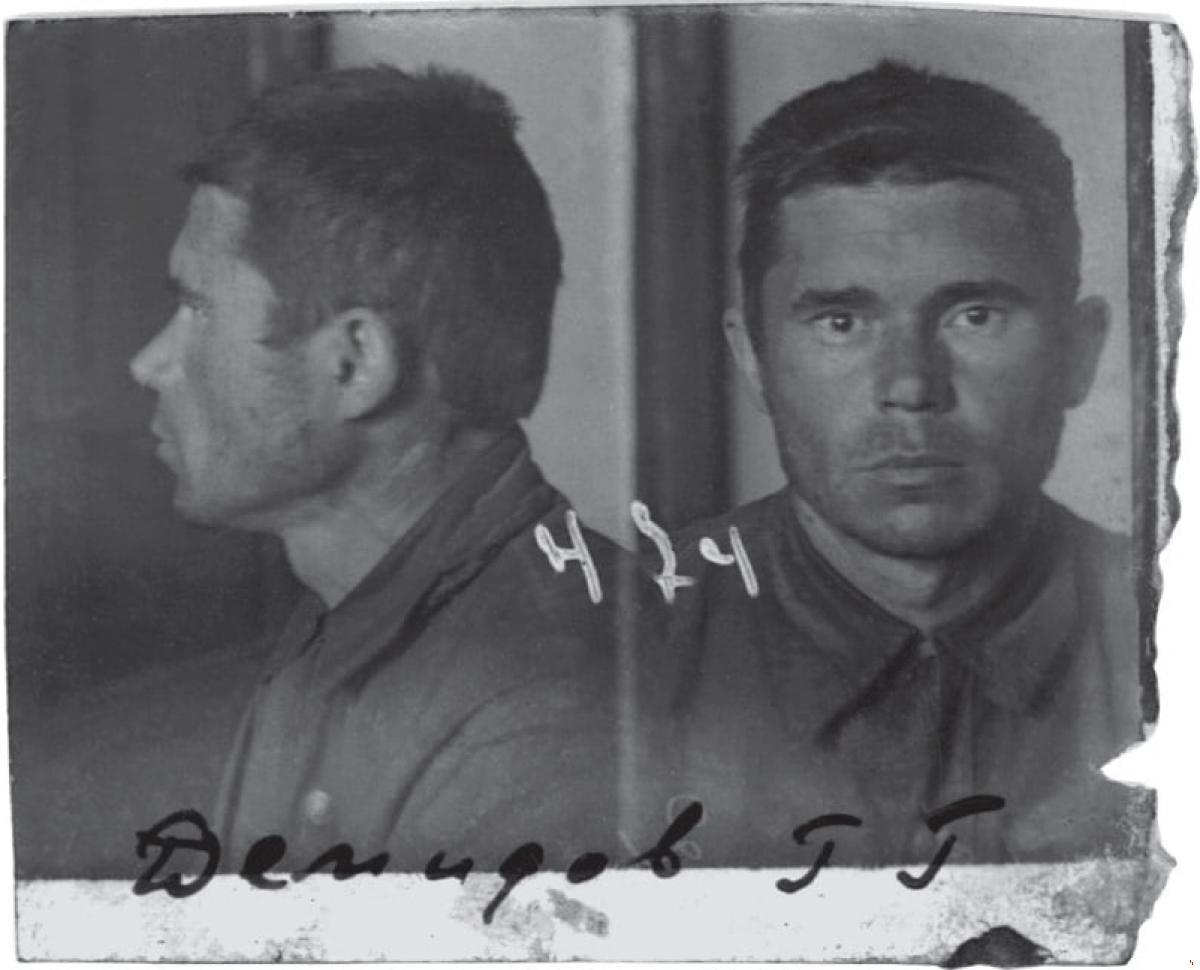

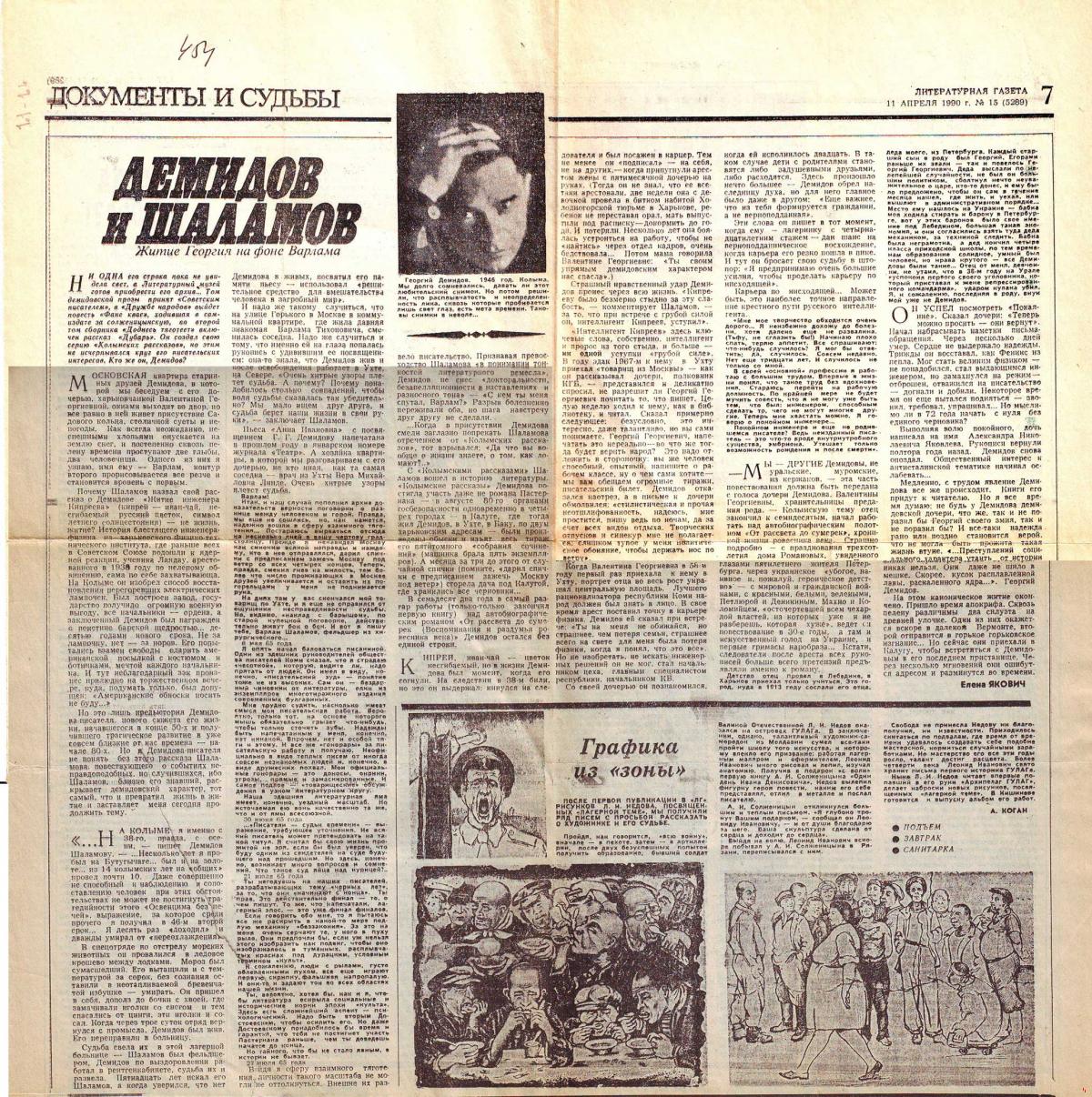

But who was Georgy Demidov? His name remained virtually unknown until the early 1990s. One of the first publications about him appeared in “Literaturnaya Gazeta” in April 1990. His fate, as the author of that essay recalls, was “captivating, as if written by a great artist.” Demidov was a brilliant experimental physicist, a student of Landau himself, who noticed him when he was just a third-year student at Kharkiv University. However, his scientific career was cut short by his arrest in 1938.

In Kolyma, where he was sent for 10 years, Demidov’s engineering genius manifested itself even in inhuman conditions: he established a production line for restoring burnt-out light bulbs for the entire Dallag. In 1946, he was arrested for a second time. In the camp, he nearly died after falling through the ice in the terrible cold. They pulled him out and, deeming him a lost cause, left him to die in an unheated hut with a body temperature of nearly forty degrees Celsius. He survived, crawled to a barrel of pine needles (used to treat scurvy), and sucked on them for three days until he was found and sent to the camp hospital.

It was there that fate brought him together with Varlam Shalamov, who worked as a paramedic. This meeting left a profound mark on both of their lives. Later, Shalamov would write: “The most intelligent and most worthy man I have ever met in my life was a certain Demidov, a physicist from Kharkiv.” Convinced that Demidov had died during a prisoner transport, Shalamov dedicated two short stories and a play to his memory, performing, as he himself put it, a “decisive means for human intervention in the afterlife.” And it “worked”: in 1965, he accidentally learned that Demidov was alive.

After 14 years in the camps and being cut off from major science—which he considered his greatest tragedy—Demidov began a “third life” as a writer. He wrote about the GULAG as he saw it—without halftones or compromises. His prose seems prophetic today: what is grotesque in the works of contemporary authors like Sorokin is harsh realism in Demidov’s. However, not a single line of his was published during his lifetime.

The end of his life was tragic. In 1980, the KGB conducted searches and seized the entire typewritten edition of his five-volume collected works. And shortly before that, his dacha, along with all his rough drafts, mysteriously burned down. At the age of 72, the writer was left without a single line he had written. He died in February 1987, just three years before the first publication about him, believing that his entire legacy had been destroyed. It was not until a year and a half after his death that the manuscripts were returned to the writer’s daughter, thanks to Alexander Yakovlev.

Thus, Loznitsa’s film is more than just a screen adaptation. It is an act of restoring historical justice and a reminder of where the conversation about the past should have begun—with repentance. And in the context of today’s war, cultural resistance, which journalist Arkhangelsky believes is a marathon and not a sprint, becomes especially important. The restoration of Georgy Demidov’s name and texts is part of this long struggle for memory and truth.

Sources:

- Elena Yakovich with Igal Margulis. https://www.facebook.com/elena.yakovich.2025

- The Inconvenient Laureate. How the Nomination of Sergei Loznitsa’s Film at the Cannes Festival Can Help the Anti-War Resistance. https://theins.ru/opinions/andrej-arhangelskij/280748

- Two Prosecutors. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%94%D0%B2%D0%B0_%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BA%D1%83%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0