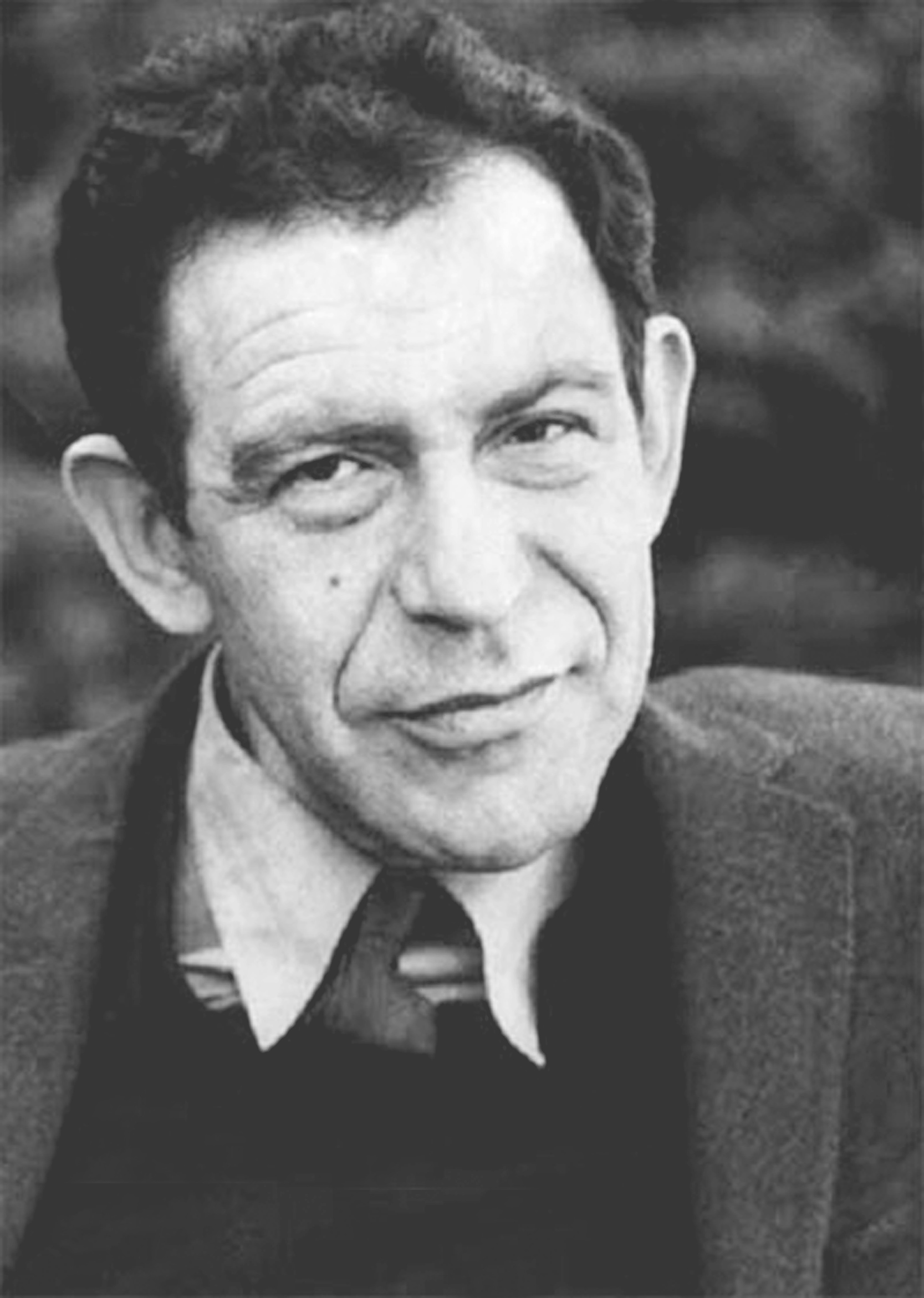

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Yuli Markovich Daniel, an outstanding translator, poet, prose writer, a defendant in the most high-profile political trial of the 1960s, and a political prisoner. Daniel’s life was closely linked to Ukraine. Here, he studied for a year in the philology department of Kharkiv University, found his wife, Larisa Bogoraz, translated Ukrainian poets, and had many friends, including his close friends Ivan and Leonida Svitlychnyi. To mark the 100th anniversary of Yuli Daniel's birth, we are publishing his biography, his final statement at his trial, and Marlena Rakhlina's remembrances of him.

YULI DANIEL'S FINAL STATEMENT

02.14.1966

I knew I would be granted a final statement. And I considered whether I should refuse it altogether (I have that right) or limit myself to a few standard phrases. But then I realized that this is not just my final statement at this trial, but perhaps the last words I will ever be able to say to people in my life. And there are people here—people are sitting in this hall, and there are people at the judges’ bench, too. And so I decided to speak.

In the final statement of my comrade Sinyavsky, there was a hopeless sense of the impossibility of breaking through a solid wall of misunderstanding and unwillingness to listen. I am not so pessimistic. I hope to recall the arguments of the prosecution and the arguments of the defense one more time and compare them.

I have asked myself throughout this trial: why are we being asked questions? The answer is obvious and simple: to hear an answer, to ask the next question; to conduct the case and ultimately arrive at the truth.

This did not happen.

I will not make unsubstantiated claims; I will recall once again how it all happened.

I will speak about my own works—I hope my friend Sinyavsky will forgive me, he spoke of himself and of me—it is just that I remember my own pieces better.

I was asked: why did I write the novella “Moscow Speaking”? I answered: because I felt a real threat of a revival of the cult of personality. They counter: what does the cult of personality have to do with it, if the novella was written in 1960–61? I say: those are the very years when a series of events led one to believe that the cult of personality was being restored. They do not refute me, they do not say, “You are lying, that never happened”—no, my words are simply ignored, as if they were never spoken. They tell me: you slandered the people, the country, the government with your monstrous invention of a Public Murder Day. I reply: such a thing could have happened, if one recalls the crimes of the cult of personality era—they are far more terrifying than anything Sinyavsky and I have written. That is all—they listen to me no more, they do not answer me, they ignore my words. This ignoring of everything we say, this deafness to all our explanations—is characteristic of this trial.

Regarding another of my works, it is the same: why did you write “Atonement”? I explain: because I believe that all members of society are responsible for what happens, each individually and all together. Perhaps I am mistaken, perhaps it is a false idea. But they tell me: “This is a slander against the Soviet people, against the Soviet intelligentsia.” They do not refute me, they simply disregard my words. “Slander” is a very convenient answer to any word from the accused, the defendant.

The public prosecutor, the writer Vasilyev, said that he accuses us on behalf of the living and on behalf of those who died in the war, whose names are inscribed in gold on marble in the House of Writers. I know these marble plaques, I know the names of the fallen; I knew some of them, I was acquainted with them, and I hold their memory sacred. But why, when prosecutor Vasilyev quoted the words from Sinyavsky's article—“…so that not a single drop of blood would be shed, we killed, and killed, and killed…”—why, when quoting these words, did writer Vasilyev not recall other names, or are they unknown to him? The names of Babel, Mandelstam, Bruno Jasieński, Ivan Katayev, Koltsov, Tretyakov, Kvitko, Markish, and many others. Perhaps writer Vasilyev has never read their works or heard these names? But then, perhaps the literary critic Kedrina knows the names Levidov and Nusinov? And finally, if such a stunning ignorance of literature is to be found, then perhaps Kedrina and Vasilyev have at least heard a whisper about Meyerhold? Or, if they are far removed from art in general, perhaps they know the names Postyshev, Tukhachevsky, Blücher, Kosior, Gamarnik, Yakir… These people, apparently, died of a cold in their beds—is that how one is to understand the assertion that “we did not kill”? So, what is it—did we kill or not kill? Did it happen or not? To pretend that it did not happen, that these people were not killed, is an insult; it is, forgive my harshness, spitting on the memory of the dead.

J u d g e : Defendant Daniel, I am stopping you. Your insulting expression is not relevant to the case.

D a n i e l : I apologize to the court for my harshness. I am very agitated, and it is difficult for me to choose my words, but I will control myself.

We are told: evaluate your works yourselves and admit that they are vicious, that they are slanderous. But we cannot say that; we wrote what corresponded to our understanding of what was happening. In return, we are not offered any other understanding: we are not told whether such crimes happened or not; we are not told that no, people are not responsible for each other and for their society; they are simply silent, they say nothing. All our explanations, like the works we wrote, are left hanging in the air, not taken into account.

The public prosecutor Kedrina, speaking here, read almost entirely from her article “The Heirs of Smerdyakov,” published in the *Literary Gazette* before the trial even began, with some lyrical digressions and additions. I will allow myself to dwell on this article, because it functions in this trial as a closing argument, and for one other reason, which I will state later. Here, Kedrina, beginning her “literary analysis” of the novella “Moscow Speaking,” writes of the novella's hero: “But he wants to kill. So when?…” The whole point is that my hero does not want to kill; this is clearly seen in the novella. And, by the way, this is not just my own opinion; the citizen presiding judge agrees with me. During the questioning of the witness Gorbuzenko, he asked: “As a Communist, what is your attitude toward the fact that the hero of the novella is ordered to kill, and he does not want to?” I am grateful to the presiding judge for this precise definition of the hero's position. No, I do not believe that the presiding judge's opinion should be binding on the literary critic Kedrina, she can have her own opinion about the work, but how is it substantiated? Here is what Kedrina writes: “the positive hero dreams of Studebakers—one, two, eight, forty of them—that will drive over corpses.” I return to this passage, it was quoted in the article and here, at the trial. And by the way, it is not written as it is quoted here; this passage was never quoted in full: “Well, and those ones, the sitting and enthroned… what about them? And what about ‘37, when the country was convulsed by a fit of repression? And the post-war madness? Are we really to forgive?” (I am quoting from memory, not exactly.) These two sentences are carefully omitted. And why? Because they contain the motives for hatred, and that is something one must argue about, explain somehow; it is much simpler to not notice them. Then comes what was quoted here: “No. Do you still remember how it's done? A fuze. Rip out the safety pin. Throw it. Get down. Get down! It blew. And now—forward. On the run—a spray from the hip. A burst. A burst. A burst…” Then, in the hero’s imagination, everything gets mixed up—“Russians, Germans, Georgians, Romanians, Jews, Hungarians, pea coats, posters, medics, shovels…”—I cite this passage, where there is indeed a bloody mess and everything else quite unappetizing: “And why is his face so thin? Why is he wearing a soldier’s shirt and a helmet with a star?… A Studebaker drove over the corpses, two Studebakers, forty Studebakers, and you will still lie there, sprawled out… All this has happened before!”

Is this called dreaming? Dreaming of Studebakers that will drive over corpses?! The hero’s horror at this picture, his revulsion—passed off as dreams! “Ordinary fascism”—that is exactly what she writes. But the claim that this is fascism has to be supported, and so Kedrina writes: “This program of ‘liberation’ from communism and from the Soviet system the ‘hero’ of the novella attempts to justify, on the one hand, with assurances that the idea of ‘public murders’ originates in the very essence of the doctrine of socialism,” and on the other, that enmity is in the nature of human society in general. Incidentally, there is not a single word in the novella about the Soviet system, about liberation from the Soviet system; the novella’s hero turns to the name of Lenin as his last resort (“This is not what he wanted—the one who was the first to lie within these marble walls”). So, who is it that is trying to “justify a program of liberation”—the hero of the novella or not the hero? When I read this in Kedrina's article, I thought, sinner that I am, that it was a misprint, a typographical error—that instead of “negative hero” or “another hero,” they simply printed “hero,” and it turned out as if it were about the same person all along, my positive hero. But no! These same words were spoken again here, in this courtroom. But what is really happening? Doesn't the hero say that “the idea of public murders lies in the very essence of the doctrine of socialism”? Well: the hero's friend, Volodya Margulis, an unintelligent and narrow-minded man, comes to see him. “He came to me and asked what I thought about all this” (“I” is the hero of the novella, speaking in the first person). And Volodya Margulis “began to argue that it all lies in the very essence of the doctrine of socialism.” So, is it the hero saying this or another character in the novella? Here is what the hero says: “We must stand up for the real Soviet power”; the hero says that our fathers made the revolution, and we dare not think ill of it. Is this the hero of the novella justifying a “program of liberation from communism and the Soviet system”? It is not true! And who says that “everyone is ready to drown each other in a spoonful of water”? That “soon beasts will be the only connecting link between people”? According to Kedrina, it is the same “positive hero.” Not true! This is said by a half-mad old misanthrope, and the hero argues with him. So what is the situation with the ideological justification of a pseudo-call for massacre, for terror, and for liberation from communism and the Soviet system? It is just as I say, not as Kedrina asserts. The novella was not read as it was written, but willfully, with prejudice; it is impossible to read it that way.

Sinyavsky and I are blamed for everything—in particular, for the fact that we have no positive hero. Of course, it is easier with a positive hero; there is someone to oppose to the negative one. And our reference to other writers who have no positive hero is perceived, first, as an attempt to compare ourselves to those great writers, and second, the response is very simple: when it comes to Shchedrin—a positive hero is present in his works, it is the people. Obviously, invisibly present, since the people depicted in *The History of a Town* evoke pity, not admiration. And in *The Golovlyov Family*, are the people the positive hero? And the reference to the tale of how one peasant fed two generals—it is simply shameful to hear. Kedrina evidently believes that this peasant, who made snares out of his own hair to get game for the generals, this peasant who voluntarily goes into slavery—is a positive image of the Russian people? Mikhail Evgrafovich Shchedrin would not agree!

I would not refer to Kedrina’s article if the entire system of the prosecution’s argumentation did not lie in the same plane. Well, how can one prove the anti-Soviet essence of Sinyavsky and Daniel? Several methods were used. The simplest, head-on method is to attribute the thoughts of a character to the author; one can go far with that. Sinyavsky is mistaken in thinking that only he has been declared an anti-Semite—I, Daniel, Yuli Markovich, a Jew, am also an anti-Semite. All by means of this simple trick: in one of my works, that same old waiter says something about Jews, and now there is this review in the case file: “Nikolai Arzhak is a consummate, convinced anti-Semite.” Perhaps this is written by some unsophisticated reviewer? No, it is written in a review by Academician Yudin… There is also this method: isolating a passage from the text. One need only pull out a few phrases, make some cuts—and one can prove anything one likes. The most convincing example of this method is how “Moscow Speaking” was turned into a call for terror. They keep referring to the émigré Filippov: he is the one who correctly evaluated your works (he, it turns out, is the supreme criterion of truth for the state prosecutor). But even Filippov was unable to exploit such an opportunity. It would seem there could be nothing better; if there were a call to terror there, Filippov would have certainly said: see how underground Soviet writers are calling for murder, for massacre. But even Filippov could not say this.

Another method: substituting the accusation of a character with a fictitious accusation of the Soviet government—that is, the author says some words, exposing a character—and the prosecution believes it is said about the Soviet government. Here is an example. The indictment is largely based on a review by Glavlit, and in that Glavlit review it literally says: “The author considers it possible to hold a Pederast Day in our country.” But in fact, it is about an opportunist, a cynic, the artist Chuprov, about how he would even paint posters for a Pederast Day just to make money; this is what the main hero says about him. Who is he condemning here—the Soviet government or perhaps another character?

In the indictment, in the Glavlit review, in the speeches of the prosecutors, the same quotations from the novella “Atonement” were repeated. And what are these quotations? “The prisons are inside us”—this is shouted by the novella's hero, Volsky. Yes, this is a powerful accusation against all people. And I was by no means trying, as Vasilyev said here, to present things as if I were engaged in fine literature; I am not trying to escape the political content of my works. There is political content in Volsky's words—but what follows these shouts? Who is shouting this? A madman is shouting it; he has lost his mind. He soon finds himself in a psychiatric hospital.

One more method, also very simple, but very powerful, for proving anti-Soviet essence: to invent an idea on behalf of the author and to say that a work contains anti-Soviet attacks when there are none. Take the story “Hands.” My defense counsel, Kiseshinsky, argued convincingly that there is no anti-Soviet idea in this story, no matter how one interprets it. In her rebuttal, Kedrina said: “Just look with what expressiveness and vividness, quite uncharacteristic of him, Daniel depicted the execution scene.” Please, I implore you, think about what you have said: vividness and expressiveness of description serve as proof of anti-Soviet essence. That was the response to the defense attorney's speech concerning the story “Hands”—and not another word. As for this story, I ask you all. When this court session ends today, and you all go home. Go to your bookshelves, take a book, open it and read about how a Red commander was assigned to a firing squad. He grew dark and gaunt on this job; he returns home, staggering as if drunk. And he is executing not priests, but grain farmers; there is even this detail, I remember it well: he recalls the hand of an executed man, calloused like a horse's hoof. He feels very ill, it is very difficult and very frightening, he even proves to be impotent as a man when he is alone with the woman he loves. Well, does this passage fit the wording of the indictment—that the class policy of repression against the Soviet people morally and physically maims people…

J u d g e : What nonsense! What class policy of repression?

D a n i e l : I am quoting the indictment, it says right here (reads): “…the alleged class policy of repression against the Soviet people.” That is what is written in the indictment. As you have probably guessed, I have just recounted a small chapter from *And Quiet Flows the Don*. The characters are the Red commander Bunchuk and Anna. How else are we accused? Criticism of a specific period is passed off as criticism of the entire epoch, criticism of five years—as criticism of fifty years; even if it concerns just two or three years, they say it is about the whole time.

The prosecutors try not to notice that Sinyavsky’s entire article is directed at the past, that all the verbs there are even in the past tense: “we killed”—not “we are killing,” but—“we killed.” And in my works, except for the story “Hands,” the subject is the 1950s, a time when the threat of the restoration of the cult of personality was real. I have spoken about this all along, it is evident from the works—they do not hear.

And, finally, one more method—substituting the object of criticism: disagreement with particular phenomena is passed off as disagreement with the entire system.

These, in brief, are the methods and techniques of “proving” our guilt. Perhaps they would not have been so terrible for us if we had been listened to. But Sinyavsky was right when he asked—where did we come from, we ghouls, we bloodsuckers? We did not fall from the sky. And here the prosecution moves on to telling what scum we are. Strange methods are brought into play: prosecutor Vasilyev says that we sold ourselves for thirty pieces of silver, diapers, and nylon shirts, that I abandoned the honest labor of a teacher and went with outstretched hand through editorial offices, begging for translation work. I could ask my wife, and she would bring a pile of letters from poets asking me to translate their poems. It was not for the easy money of a translator that I left a well-paid teaching job, but because I had dreamed of poetic work since childhood. I did my first translation when I was 12 years old. Any translator knows what kind of easy money it is. I left a secure life and exchanged it for an insecure one. I treated it as my life's work; I never did a hack job. Among my translations there may have been bad ones, and mediocre ones, but that was from lack of skill, not carelessness.

It is strange that in an area where a lawyer must be impeccable, the state prosecutor does not acknowledge facts. At first, I thought he misspoke when he said that we were aware of the nature of our works: in 1962 there was a radio broadcast, and after that, we sent “Moscow Speaking” and “Lyubimov” abroad. Forgive me, but what was broadcast? It was precisely “Moscow Speaking” that was broadcast on the radio—so did I send that novella a second time, then? I thought it was a slip of the tongue. But then it happens again: referring to Rurikov's article, the state prosecutor says—they were warned, they knew the assessment—and they sent “Lyubimov” and “Man from MINAP.” When was Rurikov's article published? In 1962. When were the manuscripts sent? In 1961. Slips of the tongue? No. The state prosecutor is adding a detail to my persona, a malevolent, anti-Soviet one. Any statement of ours, no matter how innocent, the kind any one of you sitting here might make, is twisted: in “Moscow Speaking” there is a reference to a front-page editorial in *Izvestia*—“Ah-ha, you are mocking the newspaper *Izvestia*?” Not the newspaper, but the newspaper clichés, the wooden language; they tell me gloatingly: “At last, you are speaking in your own voice!” Is talking about newspaper clichés, about wooden newspaper language, really anti-Soviet? I do not understand it. Although no, on the whole, I understand everything...

Nothing here is taken into consideration, not the reviews of literary critics, not the testimony of witnesses. They say Sinyavsky is an anti-Semite; but no one asked, how then does he have such friends? Daniel—well, although Daniel himself is an anti-Semite; but my wife, Brukhman, the witness Golomshtok, or that witness with a charming speech impediment who was here yesterday and said what a “good person Andrei is”…

The simplest thing is not to hear.

All that I have said does not mean that I consider myself and Sinyavsky to be bright and sinless angels and that we should be released from custody immediately after the trial and sent home in a taxi at the court's expense. We are guilty—not of what we wrote, but of sending our works abroad. Our books contain much political tactlessness, excess, and offense. But are 12 years of Sinyavsky's life and 9 years of Daniel's life not too high a price to pay for thoughtlessness, for carelessness, for a miscalculation?

As we both said during the preliminary investigation and here, we deeply regret that our works were used for harmful purposes by reactionary forces, and that by doing so we have caused harm, inflicted damage on our country. This was not our intention. We had no malicious intent, and I ask the court to take this into account.

I want to ask for forgiveness from all our loved ones and friends to whom we have caused grief.

I also want to say that no criminal statutes, no accusations will prevent us—Sinyavsky and me—from feeling that we are people who love our country and our people.

That is all.

I am ready to hear the verdict.