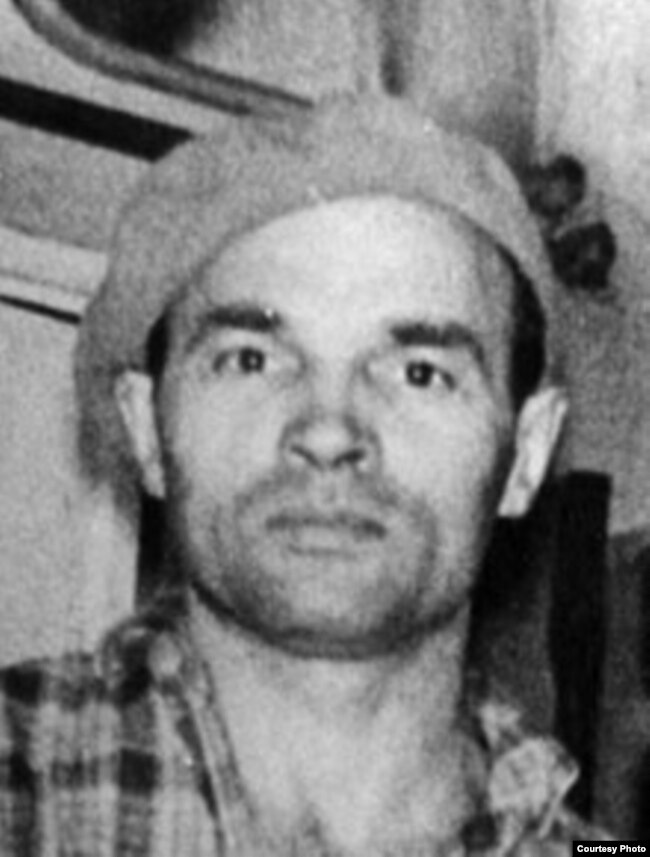

On this day in 1986, Anatoly Marchenko passed away. He was a worker by trade, a writer and human rights activist by vocation.

In September 1981, Anatoliy Marchenko was convicted for the sixth time under the article ‘anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.’ The sentence was exceptionally harsh — 10 years in a strict regime camp and 5 years of exile. While in prison, Marchenko went on hunger strike on 4 August 1986, demanding amnesty for all political prisoners, and kept it up for 117 days. Someone came from Moscow and promised him release and departure from the USSR. The official version: his heart gave out. He was only 48 years old. Marchenko's death was a shock to the human rights movement, his friends, and everyone who knew him.

In her book Postscript, Elena Bonner recalled:

“In October, we heard on the radio just once that Tolya Marchenko had been on a hunger strike since August 4. We didn't succeed in hearing anything else. We waited tensely for news the whole time, worrying. I tormented the receiver endlessly, but there was almost nothing on the radio—did that mean there was no news in Moscow either? Then, at the end of November, we heard that Larisa had been summoned to the KGB and offered the chance to leave the country—we understood this to mean together with Tolya. And here a euphoria came over us—over me especially—as if he had already been released, as if they were already leaving. I sent Larisa a postcard—a joyful one, with greetings. And every evening, twisting the dial of the receiver, I waited for reports of their departure. But on December 9 at 11:45 PM, we heard on Radio France: dead. Tolya Marchenko has died. And Larisa, with the children, went there, to Chistopol.

“It was impossible to believe. Impossible to listen. Impossible to tear oneself away from the receiver. Impossible to say anything. And one wants to scream—no, no, no. And we were silent and wept. And for some reason, in those hours and days, I kept remembering Tolya—only cheerful, only happy. How he came to us late in the evening, almost at night, at a hotel in Sukhumi—we were vacationing there, and they had just arrived from Chuna. His exile was over. Larisa stayed behind to put the children to bed, and Tolya came to us. We were eating a watermelon of some incredible size. And Andrei was proving to Tolya that he needed to leave, while Tolya insisted that it wasn't for him. Andrei, usually capable like no one else of listening to an opponent’s arguments, was irrepressible this time, almost aggressive, but arguing with Tolya was already a futile endeavor. And even though the argument was serious, everything was so cheerful, as happens, perhaps, only when a person has been set free.

“And even earlier! A cheerful, young Tolya—a happy dad with an infant in his arms—arrived from Karabanovo and disappeared with Andrei somewhere into a room. Tanya, who was in her final weeks before giving birth, lay in the kitchen on a small sofa, while Pashka crawled on her belly and smiled with a toothless mouth. Why do such things creep into one’s head—clear, carefree things? And now this news. It is hard for me to write the word ‘death.’ Every evening we listened to the radio, catching everything that was said about Tolya, and did not believe that it had happened.

“Two or three days later, a play by Radzinsky, Lunin, or the Death of Jacques, was on television during the day, on the educational channel. I cannot judge the play objectively. We were shaken by the parallels at that time. Especially the place where it is said: ‘The master thinks the slave will run, but he [meaning Lunin] is not a slave and does not run.’ I am not quoting verbatim; I ought to read the play with my own eyes now, but back then, I perceived the performance as a program about Tolya.”