Thirty-nine years ago—on October 23, 1986—Academician Andrei Sakharov sent a letter to Mikhail Gorbachev in which, after listing his contributions to science, Andrei Dmitrievich asked Mikhail Sergeyevich to “end my deportation and my wife’s exile” so that he could continue his full-fledged scientific work. In doing so, he made an “obligation not to speak out on public issues, except in exceptional cases when I, in the words of L. Tolstoy, ‘cannot remain silent.’”

An excerpt from my article “The Liberation” about the release of Sakharov and Bonner from their Gorky exile:

This letter gave the General Secretary a powerful weapon in his fight against the hard-line majority for Sakharov’s release. Gorbachev began his artillery barrage before the decisive battle with the Kremlin orthodoxes. The long preparatory stage entered its final phase.

The Decision

This is how Andrei Grachev, a member of the Central Committee apparatus at the time, recalls this period in his book “Kremlin Chronicle.”

“A phone call summoned me to Yakovlev’s office. (…) After a meaningful glance at the ceiling, which served as a reminder that ‘the enemy is listening,’ Yakovlev began the conversation unexpectedly: ‘Everything said here must remain between us.’ Although this did not bode well, it nevertheless promised an interesting follow-up. ‘Mikhail Sergeyevich asks us to discuss what to do with Sakharov. We can’t leave things as they are any longer.’ (…)

“When preparing the paper for the members of the Politburo, we inevitably had to adapt to the ethics of ‘expediency,’ a legacy bequeathed by the Bolsheviks and the party’s founder, Lenin. (…) Therefore, we could not call a spade a spade—lawlessness lawlessness and vileness vileness—but were forced to argue the ‘inexpediency’ of keeping Sakharov in Gorky any longer. (…) Such were the rules of the ‘dance with the wolves’ from the KGB that Gorbachev initiated with our participation. He expected, by applying this simple verbal anesthesia without endangering himself, to pull the teeth from their sinister jaws one by one.”

And so, after Mikhail Gorbachev provided all the members of the Politburo with the relevant reports and documents, he raised the question of a final decision on the return of Sakharov and Bonner from exile at a meeting of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee on December 1, 1986. This time (unlike in August of ’85) no disputes arose, and after a brief squabble between Gorbachev and the head “wolf”—Chebrikov—the “resolution is adopted.” Thus, the final decision to release the Sakharovs was approved at the highest level.

So what, in the end, played the main role in the decision to release them from their Gorky exile? Who brought that long-awaited day closer?

Elena Bonner: Western scientists, Western political figures, and the desire of a certain part of our leadership (I would count at least three members of the Politburo among them—Gorbachev himself, Yakovlev, and Shevardnadze) to take a clearer, more civilized stance in the international arena. This helped them in their “under-the-carpet” struggle with opposing forces in the Politburo and the Central Committee. And they understood perfectly well (they are all smart people, after all) that this would not happen without Sakharov’s release.

Mikhail Gorbachev: Sakharov was freed for the very same reasons that I decided to lead our country from a lack of freedom to freedom. It was an important part of that process. After all, to think that we were moving toward democracy while political prisoners remained in the country and an outstanding man (a representative of the intelligentsia, a democrat) was in exile would have been sheer nonsense. That is why it was a fully considered decision. But of course, to do this, we had to go through a certain period, a certain stage. It wasn't so simple. Every step was difficult.

Alexander Yakovlev: The most decisive factor was the absurdity of the exile itself. And under certain conditions, in a certain environment, it was turning into an absurdity. It was a flagrant violation of everything and anything.

We had to cleanse ourselves of that. And this release marked the beginning of such a period of cleansing. For our policy, it also gave a sort of psychological green light for subsequent actions of a similar nature.

However, two main theories about the reasons for Sakharov’s return still circulate in public opinion: 1) pressure from the West, and 2) the death of Marchenko.

Here is what A.N. Yakovlev says about the first theory:

“I am very often asked about the influence of the West. I answer: on the contrary! The more pressure there was, the sharper our reaction. Oh, is that so! You want to force us? We’ll show you!—and everything was postponed. These were very clumsy interventions.”

And indeed, the more the West pressed, the worse Sakharov’s situation in exile became. After all, no protests from the world community prevented Sakharov’s dispatch to Gorky or Bonner’s exile. Nor did they become an obstacle to the conviction of dozens of other dissidents. By and large, all this “pressure” was perceived by the Soviet leadership exclusively as interference in its internal affairs.

And it was not for nothing that during the “Era of Stagnation,” it was fashionable to expel the most active dissidents to that very same West, where they could increase the pressure as much as they liked. Sakharov was not dealt with in the same way only because of his “classified” status. So, in reality, Western pressure provided more moral support to human rights defenders than it actually influenced the decisions made by the Party and the government.

Now for the second theory. Yes, the tragic death of Anatoly Marchenko during his hunger strike in Chistopol Prison shocked and horrified many. But he died on December 8, 1986. Yes, Sakharov was still in Gorky on that day, but by then, the decision on his release had already passed through all the preparatory stages. And the political decision in principle had been made at the Politburo meeting back on December 1.

Alexander Yakovlev: Marchenko’s name was not even mentioned in passing during the discussion of Sakharov’s return. You see, our human rights movement is very often stuffed with illusions. Well, you have to connect the dots somehow.

Andrei Dmitrievich and Elena Georgievna themselves finally clarified the situation on this matter back in ’87, answering a question from the magazine “Kontinent” (No. 52):

“A.S.: The West keeps hammering away at one idea, that Sakharov’s release is a consequence of Marchenko’s death. That is completely untrue.

Nicholas Bethell: So you don’t think Marchenko’s death expedited your release?

A.S.: They are independent processes,

E.B.: Completely independent.”

What, then, influenced Sakharov’s release? It was probably, to a greater extent, the change in leadership and the rise to power of Gorbachev, who began the policy of perestroika. Perhaps Andrei Dmitrievich’s return was a kind of repentance on Gorbachev’s part for the injustice and crimes committed by his “august” predecessors. A desire to start a new policy with a clean slate...

...On December 15, a telephone was installed in Andrei Dmitrievich’s apartment. The next day, a conversation took place between Gorbachev and Sakharov, during which the General Secretary urged the chief dissident to “return to his patriotic activities.”

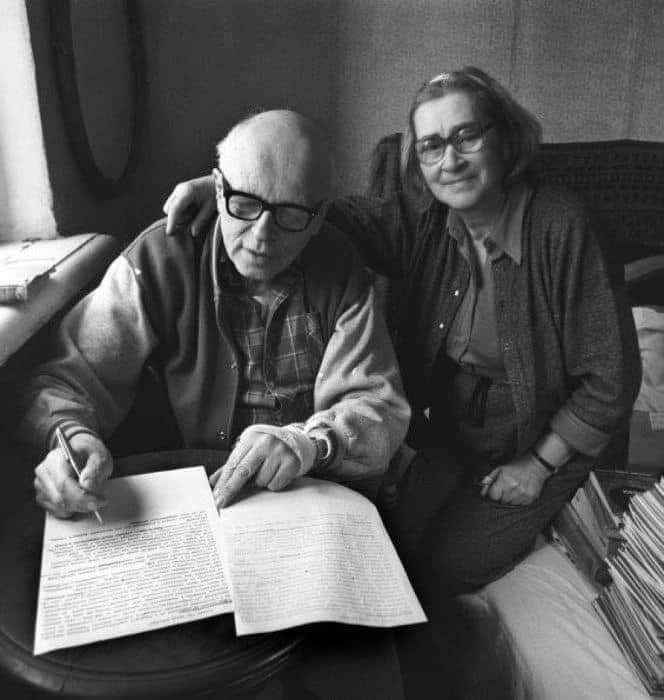

...On December 23, 1986, at 7:30 a.m., the Gorky-Moscow train arrived at Yaroslavsky station, and A.D. Sakharov and E.G. Bonner emerged onto the platform from the sleeping car. Academician Sakharov’s nearly seven-year exile and Elena Bonner’s two-year exile came to an end.

Read in full:

https://ed-glezin.livejournal.com/31297.html

https://ed-glezin.livejournal.com/31127.html

====================

Full Text of A.D. Sakharov’s Letter

To the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee

M.S. Gorbachev

Dear Mikhail Sergeyevich,

Almost seven years ago, I was forcibly deported to the city of Gorky. This deportation was carried out without a court decision, i.e., it is unlawful. I have never committed any violations of the law or of state secrets. I am being held in conditions of unprecedented isolation under continuous, overt surveillance. My correspondence is read and often delayed, and sometimes falsified. Since 1984, my wife has been in the same illegal isolation, sentenced to exile under terms which do not provide for such a degree of isolation. The verdict and the slanderous press shift the responsibility for my actions onto her.

I am deprived of the opportunity for normal contact with scientists and for attending scientific seminars, which in our time is a necessary condition for fruitful scientific work. The rare visits from my colleagues from the Lebedev Physical Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences do not remedy this intolerable situation; in essence, they are a fiction of scientific communication.

During my time in Gorky, my health has deteriorated. My wife is a Group II disabled veteran of the Great Patriotic War and has suffered multiple heart attacks since 1983. In the US, she underwent a major open-heart surgery with the installation of six bypass grafts, as well as an angioplasty on her thigh. She is now, in fact, severely disabled, requiring continuous medical supervision, care, and climatotherapy to stay alive. I am in need of the same. We are deprived of all this under the conditions of my deportation and her exile.

I repeat my pledge not to speak out on public issues, except in exceptional cases when I, in the words of L. Tolstoy, “cannot remain silent.”

Allow me to remind you of some of my past contributions.

I was one of those who played a decisive role in the development of Soviet thermonuclear weapons (1948–1968). On my initiative in 1963, the Soviet government proposed a treaty banning nuclear tests in three environments, which came to be known as the “Moscow Treaty.” You have repeatedly noted its significance. The cessation of atmospheric testing has saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

By virtue of my destiny, I have thought a great deal about the problems of war and peace. In my public activities, I have championed the principle of an open society and respect for the right to freedom of belief, information, and movement—as the most important foundation for international security and trust, social justice, and progress. In February 1986, I appealed to you for the release of prisoners of conscience—people repressed for their beliefs and nonviolent actions associated with those beliefs.

Together with the late Academician I.E. Tamm, I was an initiator and pioneer of work on controlled thermonuclear reactions (systems of the “Tokamak” type, laser compression, muon-catalyzed fusion). My proposed use of thermonuclear neutrons for the production of nuclear fuel would make it possible to eliminate the most dangerous and complex link in the future of nuclear energy—fast neutron breeder reactors—and to simplify, i.e., make safer, nuclear power reactors.

Upon the cessation of my isolation, I would like to participate in the discussion of these projects, particularly in the implementation of international cooperation programs aimed at creating peaceful thermonuclear energy.

I hope you will find it possible to end my deportation and my wife’s exile.

Respectfully yours,

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov,

Academician

October 22, 1986

603137, Gorky

Gagarina 214, Apt. 3