Dear Mr. President of Ukraine,

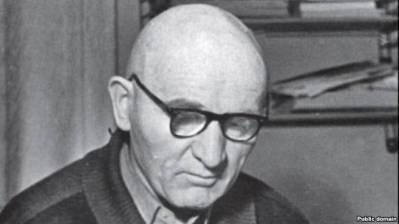

I, Vasyl Ovsienko, a prisoner of conscience with a 14-year record, am writing to you regarding the 110th anniversary of the birth of General Petro Grigorenko.

The democratic public of Ukraine anticipates a Presidential Decree on October 16 awarding Petro Grigorenko the title “Hero of Ukraine.”

Many people, myself included, believe that an independent Ukraine should have a completely new system of awards. The “Hero of Ukraine” title is a failed caricature of the Hero of the Soviet Union and Hero of Socialist Labor. This title has been awarded to all sorts of people, including many who are far from heroic, and some who are unworthy, even hostile to the idea of Ukrainian independence. It is no wonder that Lina Kostenko and Yevhen Sverstiuk refused to be ranked among them. But when the list of Heroes of Ukraine includes members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group such as Mykola Rudenko, Viacheslav Chornovil, Vasyl Stus, Levko Lukianenko, and Yuriy Shukhevych, as well as Oleksa Hirnyk, Stepan Khmara, Yevhen Proniuk, and Roman Shukhevych, then Petro Grigorenko should hold a prominent place among them. This title befits him more than most. Ukraine must ascend to a new level of its history with names like Hero of Ukraine Petro Grigorenko. These names are the honor of Ukraine. It is for people like them that the world respects us.

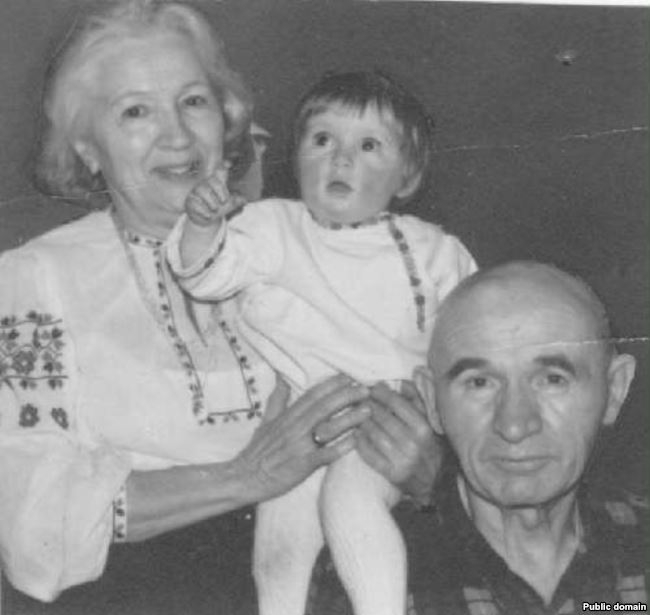

Mr. President, I hope you will resolve this matter before October 27, while Petro Grigorenko’s son, Andriy Grigorenko, president of the Petro Grigorenko Foundation (USA), is still in Ukraine, so that the award may be presented into his hands.

Respectfully,

Vasyl Vasylovych Ovsienko

October 10, 2017.

Here I will emphasize Petro Grigorenko’s most important services to Ukraine and to humanity. I have gathered these points from numerous publications, primarily from articles by Leonid Plyushch and Andriy Grigorenko.

Petro Grigorenko, like a significant part of Ukrainians, was tempted by the slogans of communism in his youth. However, he later found the strength not only to free himself from this delusion but also to rise up against it. Like Marshal Piłsudski, he “got off the red tram” when he realized it was heading into an abyss. And he set himself the task of helping other people shed their communist illusions. Grigorenko was not just a rebel. He was a strategist. Understanding the essence of the USSR as a totalitarian Evil Empire, he thoughtfully developed a strategy to overcome this evil.

Petro Grigorenko was the first representative of the Soviet ruling class who, back in 1961, spoke out against the partocracy: “We must speak out. We cannot remain silent.” On September 7, 1961, at a party conference in the Leninsky district of Moscow, he called for “strengthening the democratization of elections and broad turnover, accountability to the electorate. To remove all conditions that give rise to violations of Leninist principles and norms, in particular, high salaries and the irremovability of officials.” In other words, he spoke out against a new cult—the cult of Khrushchev. He consciously rebelled, understanding that he would lose his general’s rank, the leadership of the military cybernetics department he had created, all associated benefits, and even his pension. Moreover, he was incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital.

In late 1968, Petro Grigorenko wrote a work titled “On Special Psychiatric Hospitals (Mad-houses),” in which he was the first to raise the issue: “We must fight for a fundamental change in the system of examination and detention of patients in special psychiatric hospitals, for providing the public with a genuine opportunity to monitor the conditions of detention and treatment of patients in these facilities.” Subsequently, the USSR, cornered by evidence from Grigorenko and other human rights defenders, was forced to withdraw from the World Psychiatric Association; otherwise, it would have been expelled for using psychiatry for political purposes. With the collapse of the USSR, this monstrous evil—punitive psychiatry—was overcome, largely thanks to P. Grigorenko. Incidentally, Russia is again beginning to use punitive psychiatry for political ends. We must be wary that this political virus does not spread to Ukraine.

In 1967, General Grigorenko wrote a historical-political pamphlet, “The Concealment of Historical Truth Is a Crime Against the People!” (A response to Alexander Nekrich’s book “1941, June 22”). He was the first historian to point out that the colossal defeats of the USSR in the initial period of the Soviet-German conflict during World War II were caused not only by the total extermination of military personnel before the war but mainly by the fact that the USSR was preparing for a war of aggression while neglecting its defense.

Petro Grigorenko, like no one else, raised the issue of national oppression in the USSR. His defense of Jews, Meskhetians, Armenians, Volga Germans, Chechens, and many others, his uncompromising struggle for the right of the indigenous people of Crimea to live in their native land made him not only a hero of the freedom-loving Crimean Tatar people but also transformed Petro Grigorenko into a symbol of the fight for true equality among nations. Grigorenko is an example of genuine internationalism. Petro Grigorenko’s son Andriy wrote: “The late general was and remains a symbol of tolerance, a symbol of a true patriot who not only does not forget the pain of his own people but also responds just as selflessly to the pain of other peoples. It is precisely such a model that is so desperately needed today, not only by the Ukrainian people but by the whole world, a world being swamped by a poisonous wave of religious and national intolerance.” Ukraine now clearly lacks such champions of tolerance and inter-ethnic peace. Therefore, it is Grigorenko’s name that Ukraine must elevate to its proper height before all humanity, and right now.

During the “Prague Spring,” Grigorenko supported the democratic transformations in Czechoslovakia and was one of the authors of the open letter “To the members of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, to the entire Czechoslovak people,” which welcomed the changes taking place in that country. He also wrote a letter to Alexander Dubček with advice on the possible defense of the country in the event of a Soviet invasion and delivered it to the Czechoslovak embassy in Moscow. He spoke out in defense of the participants of the “demonstration of the seven” in Red Square against the occupation of Czechoslovakia, calling on Soviet citizens to demand the withdrawal of troops from Czechoslovakia.

To Grigorenko belongs the honor of organizing and holding the first open public opposition rally. Before the eyes of bewildered KGB officers, he delivered a speech that “entered the moral and social history of the country” (Andrei Sakharov). At a commemoration for the writer Aleksei Kosterin in 1968, he addressed the Crimean Tatars: “Stop begging! Take back what is yours by right, but has been illegally taken from you.” At Kosterin’s funeral, he said: “There will be freedom! There will be democracy! Your ashes will be in Crimea!”

He knew that only the Truth could destroy the Evil Empire. Several of Grigorenko’s works circulated in samizdat, in addition to those mentioned: “Thoughts of a Madman,” “Our Daily Lives,” “The Discrimination of the Crimean Tatars Continues,” a prison diary. He also compiled the samizdat collection “In Memory of A. E. Kosterin,” and wrote a commentary aimed at exposing the falsification by Soviet investigative bodies of data on the losses of the Crimean Tatar people after the deportation, and prepared the speech “Who, then, are the criminals?”. Samizdat became an invincible information network that destroyed the disinformation system used to manipulate the masses.

The “dissidents” were not an organization; they had no leaders, because each of them was an INDIVIDUAL. Grigorenko was not a “commander” or an undisputed authority. For Grigorenko, as a cyberneticist and a scientist, it was self-evident that samizdat was a personalistic, self-organizing system. He emphasized not hierarchy, but individuality. He was merely one of the most brilliant Individuals in this network. His own traits reflected the best within it.

Even his antipode—General Gendarme Andropov—noted that Grigorenko’s energy activated and radicalized the feeble liberal intelligentsia. And his strategic thinking found ever new forms of resistance to the re-Stalinization of the country.

Back in 1968, Petro Grigorenko initiated a discussion on the need to give the emerging dissident movement an organizational form, proposing the idea of a legalistic, that is, open, human rights organization. By the way, this idea was not accepted by Yakir and Krasin. They argued that by declaring ourselves an organization, we would be giving the KGB a list of names for arrests and a pretext for a high-profile trial of an “anti-Soviet organization.” But it was precisely openness, glasnost, that created immense moral authority for the human rights movement in society and throughout the world. And the Soviet leadership, not wanting analogies with the high-profile group trials of the 1920s–30s, did not dare to try human rights organizations as a whole: each of its members was tried separately. It was after P. Grigorenko’s second arrest that the “Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR” emerged. Later, in 1976, the Helsinki Groups were formed. It was in conversations between Petro Grigorenko and Mykola Rudenko that the idea to create the Ukrainian Helsinki Group (11/09/1976) arose, followed by the Lithuanian, Armenian, and Georgian groups. Grigorenko emphasized that the UHG, unlike the Moscow Helsinki Group, defended not only human rights, but also the rights of the nation.

Having recently been released from his second, five-year confinement in a psychiatric hospital, on Constitution Day, December 5, 1976, Grigorenko had the courage to participate in the traditional silent human rights demonstration in Moscow’s Pushkin Square, where he delivered a brief speech: “Thank you to all who came here to honor the memory of millions of innocently destroyed people! Thank you to all of you also for expressing solidarity with prisoners of conscience by your presence here!”

The general, together with his countrymen in the diaspora, laid the foundation for the revival of an independent and democratic Ukraine. Finding himself in exile, he created and headed the Foreign Representation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, which effectively became the unofficial embassy of independent Ukraine long before its appearance on the world’s political map. Largely thanks to the FR UHG, and to Grigorenko personally, the Ukrainian human rights movement entered the international arena. After 1917–1920, the world had forgotten about Ukraine. Thanks to the human rights movement, thanks to Grigorenko, the world learned about a Ukraine that exists and that is fighting for human rights and for its independence. It was a brilliant insight: to place the Ukrainian national interest on an international legal footing, in the context of the confrontation between the democratic West and the totalitarian East. This path proved to be the right one: in just a decade and a half, Ukraine became free—without a war of national liberation, without violence.

Grigorenko was a conductor of Yuri Orlov’s brilliant idea to transform the West’s capitulationist “détente” into a fulcrum for the human rights movement. As Orlov himself emphasizes, “the central figure for us was Major General Petro Grigorenko.” The doors to the offices of US presidents and European leaders opened for Grigorenko. Reagan’s famous phrase about the “Evil Empire” did not arise without the influence of Grigorenko’s letters and statements. The Soviet occupation of Afghanistan finally forced the US to stop its Munich policy of “détentism,” to expose Moscow as an international gendarme, and effectively to disrupt the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow.

Grigorenko traveled to almost every country in Europe. One of his goals was to create Helsinki Groups there. They became a public resistance to the capitulationist policies of their governments, pressing both their own governments and the government of the USSR to comply with the Helsinki Accords. It was largely thanks to Grigorenko’s strategic political mind and his personal popularity in the world that the Helsinki movement became international.

In 1980, already gravely ill, Grigorenko traveled across Europe, preparing the ground for the Madrid CSCE follow-up conference. He was sustained only by his spirit and sense of duty. His position was radical: the West must demand that the USSR respect human rights. If people continue to be persecuted for their participation in the Helsinki movement, the West must terminate the Helsinki Accords. Of course, he was speaking of monitoring compliance with the Helsinki Accords, of an ultimatum-like stance from the West, which US President Ronald Reagan would later adopt.

Grigorenko convinced the Ukrainian diaspora that at that time, legalism, glasnost, and samizdat literature had become the main tools in the fight against the totalitarian Soviet regime. He supported the activities of the Washington Helsinki Guarantees Committee for Ukraine. Together with Nadiya Svitlychna, he established the publication of the “Herald of Repression in Ukraine,” which was published in Ukrainian and English. Its materials were broadcast into Ukraine by Radio Liberty. It was a powerful pickaxe that, along with other factors, brought down the Soviet empire.

On behalf of the UHG, the WCFU, and the Lithuanian, Latvian, and Belarusian World Congresses, Grigorenko presented a Decolonization of the USSR Act to the UN. By doing so, he took an important trump card from the Kremlin’s hands—its hypocritical support for the struggle of colonial peoples for their independence (while the USSR itself contained 100 colonial peoples!). The decolonization of the USSR seemed incredible in 1980. Let us recall: even in 1989–90, US President Bush Sr. and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher spoke out against Ukrainian independence. But decolonization became a reality a decade later. Because world political thought had already been prepared by the statements of dissidents from various republics, including Grigorenko.

P. Grigorenko constantly sought to unite the struggle of all the nations of the USSR against the empire. In particular, he consistently emphasized that without the support of Russians, the decolonization of the USSR was impossible. Such a position drew constant attacks against Grigorenko. Ukrainians abroad were shocked by Grigorenko’s assertion that Russians themselves were slaves of the empire, and in this sense, the USSR was not a Russian empire, but an empire of the partocracy: “This empire is a threat to the whole world. Therefore, the fight for its decolonization cannot be the cause of a single nation. This is the task of the entire world.” Most political parties in the diaspora accepted this line, referring to the writings of L. Poltava, that is, to the position of the OUN in the 1940s. Even today, without the support of Russian democrats, effective resistance to Putin’s fifth column is impossible. It is a pity that the Russian intelligentsia in Ukraine, let alone in Russia itself (with the exception of a few individuals, such as Valeriya Novodvorskaya), does not rise to this supremely important idea. It is a pity that not all Ukrainians understand that any Russophobia helps the fifth column.

Even in his death, Grigorenko managed to unite people of different views. At his funeral in Bound Brook, there were Ukrainians and Russians, Armenians and Jews, Crimean Tatars and Native Americans, Christians of various denominations, Jews, and Muslims.

His struggle for universal human rights not only did not contradict healthy national patriotism but, on the contrary, promoted it and added respect in the world. For one can belong to humanity only through a particular nation, a particular culture. Once, as a teenager, having realized he was Ukrainian, he never forgot it, even when he considered himself a communist. Like Taras Shevchenko, he left Ukraine as a teenager but did not succumb to Russification. He carried Ukraine in his heart throughout his life. This is an excellent example for denationalized Ukrainians outside Ukraine, and even within Ukraine itself.

Grigorenko opened and showed other people the way to goodness. The main idea of Grigorenko’s memoirs, “In the Underground, You Can Only Meet Rats…” (published in several languages), is this: good cannot be born from crime; a person has the right to sacrifice only themselves, and no one else; there is not and cannot be an idea in the world that would justify a single innocent tear. These memoirs are his confession. He found the strength to repent for his participation in the Communist Party. Such a confession requires considerable courage. He returned to the faith of his childhood—and this too is a good path for others.

In the 1970s and 80s, Petro Grigorenko was the most popular Ukrainian in the world. He represented Ukraine in the best possible light, for he himself was a man of the highest moral virtues and selfless civic service. His fearlessness and sense of dignity inspired other people.

Petro Grigorenko is an individual of planetary scale. He raises the prestige of Ukraine to an international level. Only those who are interested in keeping Ukraine at a provincial level fail to understand or refuse to accept this. Conscious Ukrainians, however, are proud that there was such a Great Ukrainian—General Petro Grigorenko. And let young people know that to belong to the nation of Petro Grigorenko is prestigious, it is an honor. The younger generation of Ukrainian citizens should be educated on the example of this truly heroic figure.