On May 19, in the new conference hall of the International “Memorial” in Moscow, an evening was held in memory of Lev Zinovyevich Kopelev (1912–1997)—an outstanding writer, German philologist, war veteran, later a camp prisoner and dissident, and a public figure in the USSR and in emigration in Germany.

April 2012 will mark the 100th anniversary of Kopelev’s birth, and the event at Memorial launched a series of evenings, academic seminars, and public discussions dedicated to L. Z. Kopelev, which will take place in Russia, Germany, and Ukraine in the lead-up to the anniversary.

The evening was hosted by Irina Shcherbakova, head of the Center for Oral History and Biography at International “Memorial,” and Jens Siegert, director of the Moscow office of the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Vladimir Batsunov, a member of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, presented a new edition of three volumes of L. Z. Kopelev’s memoirs: “And He Created an Idol for Himself,” “To Be Preserved Forever,” and “Soothe My Sorrows” (Kharkiv: Prava Lyudyny, 2010, in 4 volumes), prepared by the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group and published with the support of the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

The evening began with a screening of a television interview with Kopelev, after which Maria Orlova, the daughter of Raisa Orlova, Lev Zinovyevich’s second wife, described his life path and his multifaceted creative and public activities, illustrating her story with numerous photographs from the family archive. “He managed to do everything,” Lev Kopelev said the day before he died, but we still do not know everything he accomplished, because much still lies in archives, Maria Orlova noted.

Wolfgang Eichwede, a historian and professor at the University of Bremen, who had received the Alexander Men Prize the day before, spoke about the significance of Lev Kopelev in changing German attitudes towards Russian culture and the Russian intelligentsia in the post-war period. Kopelev was the first to speak openly about the crimes of Soviet soldiers in East Germany in 1945, which he himself had witnessed—it was because of these statements that he ended up in the camps; in his later years, he collected testimonies about this—the archive contains 20,000 letters addressed to him when he lived in Cologne, many of them from women who were raped by Soviet soldiers.

Journalist Rainer Meyer explained why he intends to write a biography of Kopelev—while the events of the first part of his life were described by Kopelev himself in his autobiographical books, the second half of his life, the German period, remained undescribed and unstudied, although it too was of enormous importance. In particular, this period includes his dialogues with H. Böll and his polemic with Solzhenitsyn, his comrade from “the first circle.” The 10 voluminous tomes of the Wuppertal project, prepared by Kopelev and dedicated to Russian-German relations, are very important (so far, materials from only one volume have been translated into Russian).

Writer Yakov Drabkin, who met him on the Northwestern Front in the second month of the war, Sergei Kovalev, Lyudmila Alexeyeva, who was friends with his daughter Elena, Vladimir Lukin, who arranged a meeting for Kopelev with Boris Yeltsin in 1991 or 92, and Marlen Korallov shared their memories of communicating with Kopelev in different years.

The recollections of Pavel Litvinov, the husband of his eldest daughter Maya, were particularly detailed and insightful. “His main quality was kindness,” Litvinov noted. “He was once criticized and called an ‘abstract humanist.’ ‘I am not an abstract humanist, I am a concrete humanist,’ he would reply. Kopelev was a man of direct compassion. For example, he helped raise money for Bulat Okudzhava’s surgery in Germany in 1991. Many people are grateful to him, although there are also many ungrateful people in whom his active responsiveness caused irritation. He was intelligent, but he always spoke from the heart.”

Kopelev played a major role in the fate of Solzhenitsyn, a completely unknown author with no connections to Moscow’s literary circles, when Kopelev and Raisa Orlova brought the manuscript of “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” to Tvardovsky.

Pavel Litvinov told a remarkable story concerning the famous “demonstration of the seven” on August 25, 1968: “When we decided to organize a demonstration in Red Square, Maya, with whom I was not yet married, and I went to see Lyova and Raya, who, by coincidence, had just returned from Dubna. They were visiting Galich. There is a famous song by Yuliy Kim about how he ‘went to the Moscow suburb of Dubna to see the living Galich,’ and Lyova was there at that very moment. And that’s when Galich sang his song ‘Do you dare to go out to the square…’ for the first time, and Lyova remembered it. This was on August 23, two days after the invasion of Czechoslovakia and two days before our demonstration.

Maya and I came to visit them on Krasnoarmeyskaya Street near the airport, and he immediately started talking about his trip to Dubna, about Galich, and sang us that song. He may not have sung it badly, worse than Galich of course, but the song was wonderful, we liked it, and as Raya Orlova writes in her memoirs (though I don’t remember this), I said: ‘A very timely song.’”

The meeting was complicated, because Raya, Raisa Orlova, sensed with her woman’s intuition that I was about to do something. I was at the center of our dissident circle at the time, and then came the invasion of Czechoslovakia, and we came to see Kopelev. I told Maya beforehand that we would not talk about the demonstration, because I understood that if Lyova suddenly wanted to go, and with his temperament and the zero distance between thought and action, he very well could have gone. I would never forgive myself for that. Although he wasn't that old, he was no longer a young man, wounded at the front, had been through the camps, and we did not want to expose him to risk. So we said nothing.

We went for a walk, and he repeated the same words: now is not the time for writing letters, that won’t change anything, something must be done, we must appeal to the workers! I remember this phrase, such communist reflexes suddenly appeared. We parted without saying goodbye, and the next time they came to visit me was in exile, where Maya and I lived—they stayed with us for a week.”

In various sources, including Wikipedia, it is said that Alexander Galich’s “Petersburg Romance” (with the words “Can you go out to the square, / Do you dare to go out to the square / At that appointed hour?!”) was written in response to the “demonstration of the seven.” From Pavel Litvinov’s story, it is clear that the song actually anticipated this civic action, and Lev Kopelev and Raisa Orlova’s trip to Dubna symbolically linked the two events.

Jens Siegert, Irina Shcherbakova, Maria Orlova

Maria Orlova

Wolfgang Eichwede

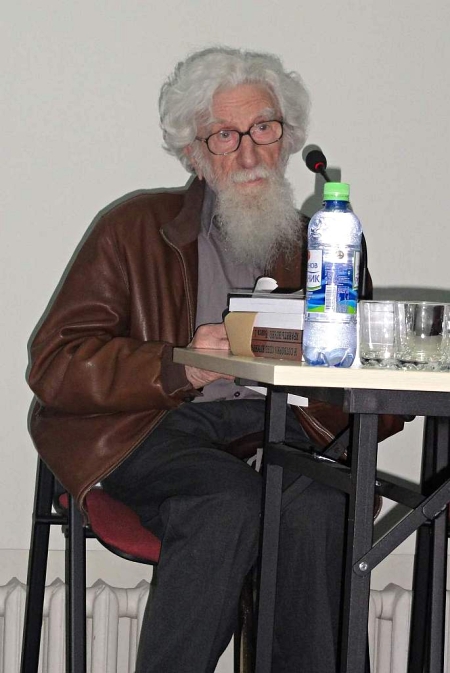

Yakov Drabkin

Rainer Meyer

Sergei Kovalyov, Irina Shcherbakova

Lyudmila Alexeyeva

Vladimir Lukin, Irina Shcherbakova, Maria Orlova

Pavel Litvinov

Marlen Korallov

Vladimir Batsunov

Photo by the author