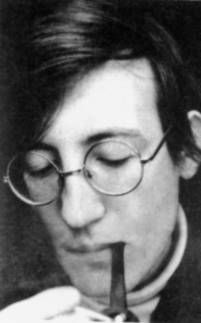

Serhiy Naboka is a living history of dissent. He was imprisoned for organizing the “Ukrainian Democratic Club.” From 1981-1984: three years in the zone, alongside murderers and rapists.

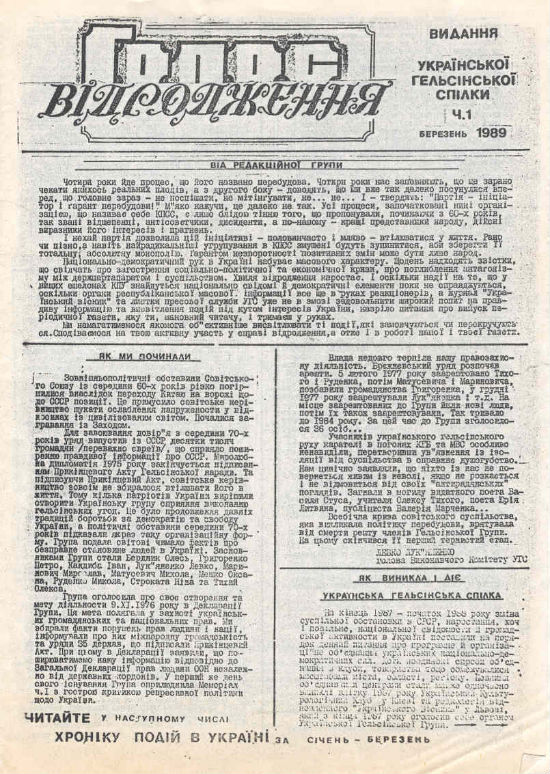

Serhiy Naboka is a living legend of Ukrainian journalism. In 1989, he created the first mass, uncensored newspaper in Kyiv—“Holos Vidrodzhennya” (The Voice of Revival). He always remained independent—in his newspaper columns, his radio broadcasts on “Radio Liberty,” and in live appearances on unfree TV.

***

He woke up famous twice.

In early 1981, immediately after his arrest, Western radio stations briefly reported on a foursome of Kyiv intellectuals—Serhiy, Inna Cherniavska, Larysa Lokhvytska, and Leonid Miliavsky, arrested for distributing some leaflets. But that was a popularity for the select few—those who had the time and inspiration to spend hours with an ear glued to radio receivers, tuned to the free voices:

“I was an editor at the ‘Mystetstvo’ publishing house and at the same time a correspondence student in the journalism faculty. And people with a certain worldview gathered around, different people, but everyone understood that Ukraine must be free. We drank, organized philosophical and religious seminars, discussed things. Well, we had to get organized somehow, so we came up with the ‘Kyiv Democratic Club.’

We were disconnected from the Ukrainian movement in Kyiv because most of them had been nabbed in 1972, and the rest were lying low and only communicating among themselves.

Of course, I respected and bowed down before the people who declared themselves members of the Helsinki Group, who acted openly and knew where they were headed. We also knew that sooner or later we would be imprisoned, but we wanted to get imprisoned a little later, after having managed to do at least something. At least something!”

From the autumn of 1987, from the very first scathing exposé in “Vechirniy Kyiv,” he became known in his native land as well.

For me personally, the name Serhiy Naboka began to be associated with the concept of “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism” long before the names of Viacheslav Chornovol, the Horyn brothers, and Levko Lukianenko.

The brutal campaign in the capital’s press sparked curiosity, reinforced by a desire to hear for myself what the “gentlemen from the UCC,” the “concerned citizens,” the “extremists from the Democratic Union” really wanted.

“...It was a certain impetus. I felt that I was doing something useful and necessary. I like it when there’s pressure on me. When there’s pressure, it means I’m alive. At that moment, I felt—oh, the scumbags are stirring, they’re lying, writing vile, disgusting, idiotic, KGB-style articles, but it was also pleasant—yes, we are doing everything right! We must, then, push forward, build up our strength, onward, guys!”

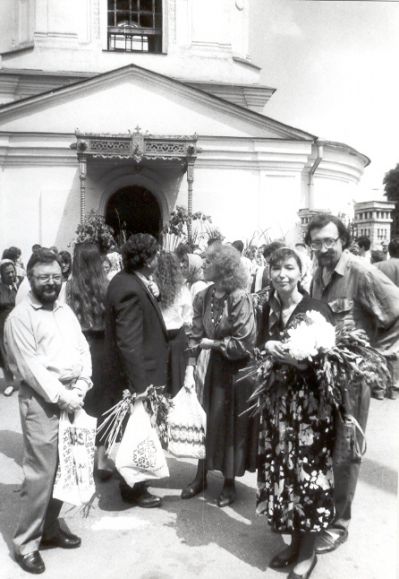

At Trinity in 1989: from left to right: Leonid Miliavsky, Larysa Lokhvytska, Inna Cherniavska, Serhiy Naboka

Unwilling to popularize the “especially dangerous state criminals” who had just returned from camps and exile, the authorities made a fatal mistake—they started writing about Naboka and other active “informals.”

“Serhiy Naboka, a native of the city of Tula, is not employed anywhere, having left his position as a loader at a grocery store. He was once sentenced by the Kyiv City Court to three years of imprisonment” (organ of the capital’s city committee of the CPU “Prapor Komunizmu,” March 5, 1989).

This is not a stylization of the sadly memorable Soviet party journalism. This is a real, albeit torn from its original (in fact, quite unoriginal!) text, fragment of one of hundreds of articles about those who “under the cover of demagogic slogans in support of perestroika….” And so on, and so on…

Naboka would have remained in the history of our independence even if he had done only one thing—founded the Ukrainian Culturological Club. Or, as was then fashionably and pointedly anti-Soviet to say, the “clyub.”

The semi-legal organization existed for about two years: if they managed to rent a café somewhere on the outskirts—good; if there was a private house and a small room—so be it.

The resonance from the UCC’s discussions was tremendous. The mere impressions from personal communication with Naboka, Oles Shevchenko, or Yevhen Sverstiuk at that time freed people from Soviet delusions better than any agitprop.

In other words, Naboka and the other UCC members managed to break the “information blockade” and even turned the situation to their advantage.

The club’s meetings were attended by hundreds of people. The diligent party press, which printed letters from veterans in every issue, provided the UCC with some great PR!

The word “culturological,” as Naboka himself admitted, was nothing more than a well-chosen cover.

“We were all perfectly aware that our organization was anti-Soviet, anti-communist, and nationalist. I was simply driven by the desire to do something. I didn’t know what to do, but I knew that something had to be done, even despite the conviction of some, perhaps somewhat tired, overly lethargic, or old ‘ex-prisoners,’ or some ‘smart alecks’ who were convinced that nothing needed to be done because nothing would come of it anyway.”

The communists did a thorough job of cleansing the human stock. They diligently and methodically culled the good “sheep” until only those who meekly went to the slaughter remained. If not for Gorbachev’s reforms, conscious Ukrainians would have disappeared before the start of the new millennium. They wouldn't even have needed to be killed; they would have died out on their own like mammoths or degenerated like Belarusian-speaking Belarusians.

As Serhiy Naboka later wrote, the prevailing opinion at the time was that “any initiative not sanctioned from above (even one that was completely innocent—like, say, collecting signatures to protect architectural monuments) was perceived in the society of the time as an enterprise doomed to failure from the start: there was a conviction that any spontaneous step would provoke a flood of repressions.”

Naboka and his friends were not the bravest. They simply realized more clearly than others that their own children would no longer have the opportunity to be Ukrainians.

A new historical community—the single Soviet people—was not a propaganda trick, but a historical inevitability. Hence the audacity, the cynicism, with which the UCC spat on prohibitions.

“Once, a KGB colonel called me for a talk in a park. I was always curious about what they wanted from me; I was already a member of the All-Ukrainian Coordinating Council of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union at that time. He said that we were number four or three on the list for imprisonment. And I ended up in some nice company with Khmara, Chornovol, and others. I really liked that…

He said—but you are not extremists in the culturological club, you don’t raise the issue of ‘Ukrainian independence.’ The next day, I convened the club and said: let’s not forget that our goal is an independent Ukraine.

That day was not so much a meeting as a ‘reminder’—let’s not forget whose children we are and what our goal is.”

As a nationalist, Naboka couldn’t help but have good contacts with nationalists of other enslaved peoples—primarily, the Baltic ones. From Vilnius, Riga, and Tallinn came packages with documents from the popular fronts, postcards in national colors, and samvizdat.

As a journalist, Naboka couldn’t help but become the editor of an independent newspaper. But before that, he turned down Chornovol’s offer to join the editorial board of the newly revived journal “Ukrayinskyi Visnyk”—saying that we and our like-minded people declare anti-communism, while your program has some unacceptable Marxist theses.

“Because—either you’re a Ukrainian, or you’re a communist! Either you’re, damn it, a democrat, or you’re a communist! Either you want to build an independent state, or you’re a communist! Tertium non datur, ever! Which is what we see. It’s been confirmed—you can’t build anything with communists. So the communists are building for themselves—these Kuchmas, Kravchuks…”.

In March 1989, Serhiy Naboka entered the annals of our national history as the one “responsible for the publication” of the newspaper “Holos Vidrodzhennya” (The Voice of Revival). A combination of modesty and a laid-back attitude prevented him from calling himself “editor-in-chief.”

“I started hammering the UHU leadership about the need to raise this issue at the coordinating council—we need it, guys, we need it! It’s time to publish a ‘combat leaflet.’

Everyone agreed, but no one budged. So my wife Inna and I sat down: I write the texts, she cuts, pastes, and we make a layout. I secretly take it, on the sly, by commuter trains with transfers through Minsk, to Vilnius. I give, I think, a hundred rubles—for a thousand copies of a trial run of ‘The Voice of Revival.’ We published several issues just the two of us at home.

I didn’t ask anyone’s permission and did it with my own money. I’m a journalist, editor, and publisher by nature, so to speak. I wanted to do it, it was interesting for me to do it.”

It was a bombshell! The little newspaper with its “blind” and, admittedly, rather clumsy text was snatched from people’s hands. A print run of ten thousand flew off the shelves in a few days, even though the price of this newspaper was dozens of times higher than any official publication of the time.

So, couriers from the ranks of UCC and UHU activists (what were they if not agents of Lenin’s “Iskra”?) took the layout again, their backpacks, and off to Lithuania they went. The authorities were going crazy from such audacity.

Serhiy never saw his first book of poems; it was published by his friends.

“Among the characteristic features of Naboka’s ‘editorial style’ should be included the crude profanity addressed to many of our fellow citizens. Thus, he calls the famous writer, people’s deputy of the USSR Valentin Rasputin a ‘hideous imperialist.’ ‘The Voice of Revival’ subjects other people’s deputies to similar insults—the worker from Zaporizhzhia, Kalish, the renowned healer-ascetic Kasyan, the internationalist-warrior Chervonopysky...” (organ of the Central Committee of the CPU “Pravda Ukrainy,” October 13, 1989).

Unlike most of his colleagues and like-minded people, Naboka did not go into politics. He clearly distanced himself from it in the spring of 1990, when the UHU transformed into the first pro-independence party—the URP.

Having no desire to become a party journalist, he set off on a freelance voyage—creating the first news agency in Ukraine, UNIAR, and helping many now-famous journalists realize their potential.

“I never liked to be in the front ranks. Sometimes you just have to. Back then [in the late 1980s] I had to, because I knew that if it wasn’t me, then that’s it—we’d be sitting in shit. I spoke at rallies until the moment normal politicians appeared who wanted to be involved in politics, or simply knew they needed it. As for me personally, I didn’t really need it.”