We have already written about how Muscovite Georgy Shakhet tried to gain access to the criminal case file of his grandfather, Pavel Zabotin, who was executed by firing squad in 1933 under the decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of August 7, 1932, “On the Protection of the Property of State Enterprises, Kolkhozes, and Cooperatives and the Strengthening of Socialist Property”—the notorious “Law of Three Spikelets.” We now present the story of Marina Agaltsova, a lawyer with the Memorial Human Rights Center, who represented Shakhet’s interests in court.

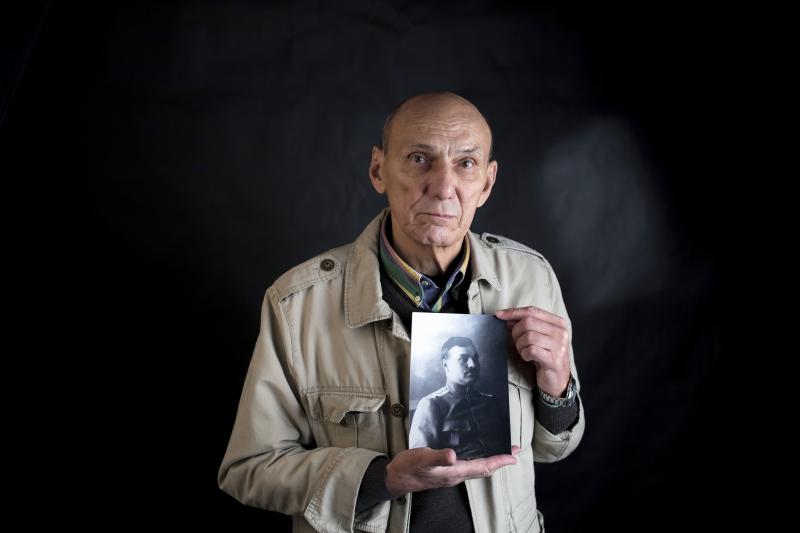

Georgy Shakhet

Episode 1: “Why?”

I’m not a fan of requests to “just go to court.” To have a normal dialogue with judges and not feel like an idiot, you need to understand the facts and the legal framework.

“But we can’t just let such a sweet old man go to an appeal by himself. Yes, we understand you didn’t work on the case in the court of first instance. But maybe you could help?” Irina from the historical “Memorial” asked cautiously in September 2018. The historical “Memorial” is engaged in researching Soviet repressions. Closed archives, and thus the impossibility of understanding what really happened, are a particular source of pain for “Memorial.”

As always, there was no time, but Shakhet’s case, concerning the denial of access to the files of a grandfather shot in 1933, stirred up some old thoughts.

August 2016, Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina). A chill was descending from the surrounding mountains. I wrapped myself in a blanket on the cafe balcony, but my feet were freezing in my light sandals. Lights flickered back and forth in the evening air.

To my right sat Charles from Rwanda. He looked like a typical Tutsi—nearly two meters tall and very thin.

Charles was the only one in his family who survived the genocide. In 1994, the Hutu—an ethnic group in Rwanda—systematically murdered another ethnic group, the Tutsi. In three months of slaughter, the Hutu killed about a million Tutsi. And they raped about 500,000 Tutsi women.

“Why didn’t they kill you?” I asked, surprised by the clumsiness of the question.

“They didn’t have time. After they had slaughtered my family, the leader of the local Hutu suddenly pointed at me and said: ‘Don’t touch him. He will be the last Tutsi we kill. Let our children remember what these traitors looked like.’ So I survived. Three months later, the Patriotic Front won the civil war and the genocide ended.”

Charles spoke deliberately and with almost no emotion. The French in which we conversed gave his words a melodic, airy quality. To an outside listener, our conversation might have seemed like polite chit-chat. But what I heard made me nauseous, a nasty lump formed in my throat, and a dull ache spread through my chest.

“In three months, the Hutu killed one-eleventh of the country... How could the Tutsi live side by side with their murderers and rapists after that?” I asked, swallowing the lump.

“The new government worked skillfully with the national memory. Before the genocide, the division into ethnic groups was everywhere: on passports, in schools, at work. After the genocide, the government abolished this division. The unification of the Rwandan people became a national idea and the main political narrative.”

The Rwandan people wanted the truth: how it was that a million innocent people were killed in a hundred days. They also wanted to find the bodies of their murdered relatives, and to find and prosecute the criminals (the “génocidaires,” those who committed genocide).

By 2000, 130,000 génocidaires awaited trial in Rwanda. The state courts would have needed about 200 years to “process” such a number of defendants. So, the country established 12,000 informal, “grassroots” courts, which heard the executioners’ cases. The essence of these courts was to get to the truth and restore peace. Since 2004, 850,000 people accused of genocide have passed through these courts.

I listened in amazement to the one-and-a-half-hour lecture on the enormous work being done on the collective consciousness of the Rwandan people. And one question buzzed in my head like an annoying mosquito. Our people also survived the horror of the Stalinist repressions. According to official data from the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs alone, from 1921 to 1954, 3.8 million people were repressed for political reasons. About 700,000 of them were executed by firing squad. Neither in the nineties nor later was any work done on “living through” the tragedy. How do we stand with our historical memory of the terrible repressions? Has the collective gestalt been closed?

* * *

Two years later, when Irina from the historical “Memorial” asked me to take on Shakhet’s case in the appeal, I remembered the conversation in the Sarajevo cafe and realized: this was my chance. A chance, through a socio-legal experiment, to understand whether we as a people are ready to discover and accept the truth about the Stalinist repressions.

And this experiment began with a case about archives.

Episode 2. “The Courts”

“You want the Moscow City Court to order the prosecutor’s office to send Zabotin’s case to court for rehabilitation? But we can’t order it! That’s within its discretionary powers,” the chairman of the appellate panel of the Moscow City Court scowled.

Together with “Team 29,” we had been fighting for two years to help the actor Georgy Shakhet gain access to the case file of his grandfather, Pavel Zabotin, who was executed in 1933. Pavel was not rehabilitated, so access to the documents is possible only after his rehabilitation. We went to the prosecutor’s office to seek rehabilitation. But the prosecutor’s office doesn’t want to rehabilitate him. It believes he was executed correctly, without political motives.

Pavel Zabotin

“Look, there’s a law on the rehabilitation of victims of political repressions. It contains two mechanisms for rehabilitation. The first is through the prosecutor’s office. If the prosecutor’s office sees that the executed person was repressed for political reasons, it rehabilitates him itself. If the prosecutor’s office believes there are no grounds for rehabilitation, it sends the case to court. So that a court, in an adversarial process, can review the sentence and decide: should a person have been shot for stealing glass and bricks or not,” I explained that sending cases to court is mandatory for cases judged by “troikas,” i.e., extrajudicial bodies, as in our case. The person did not have a proper adversarial trial with a lawyer. What’s more! He could not even be present at the trial. And he could not appeal the verdict. In the fight against “enemies of the people,” they didn’t bother with such trifles. Therefore, in this category of cases, the prosecutor’s office does not have discretionary powers. It is obliged to send the case to court, even if it believes there are no grounds for rehabilitation.

“Your Honor,” I continued, “we applied for a review of the 1933 verdict to the Moscow City Court under the second mechanism of the rehabilitation law. Under this mechanism, one can appeal if there is no political motive in the criminal case, or if the person was convicted on a combination of political and non-political charges. And the Moscow City Court refused to hear our case. It said that this was clearly a case of political repression. And that it must go through the prosecutor’s office. And that a cassation appeal is not possible. It turns out that if you deny our appeal of the prosecutor’s decision, there is no way to review the verdict. A death sentence for stolen glass and bricks, handed down in secret, without a trial, without the accused, will then remain unreviewed. Therefore, we ask that our appeal be granted.”

But, apparently, my request was not persuasive enough. The decision was upheld. We will appeal further. And prepare a complaint to the Constitutional Court.

Episode 3. “In the Archives”

“You are not allowed to take your own photographs in the reading room. Only by contract. Please delete all the photos,” said the reading room employee politely, handing me two copies of a contract.

Damn it! It’s not that I mind paying 30 rubles to photograph a single page. But Russian archives have a dreadful bureaucracy. You have to count the pages, fill out the contract, and wait five days for it to be signed. Only then can you come back to take photos.

Every country has its own archival quirks. In America, for example, you can’t drink or eat while working. And you can’t touch documents without green gloves. But you can take pictures. In Russian archives, you can drink, eat, and go gloveless, but you can’t take pictures.

I was in the archive looking for documents related to the development of the law on the rehabilitation of victims of political repressions. In the Shakhet case, the courts are interpreting the law strangely. They are denying access to the criminal case file of Shakhet’s grandfather, executed in 1933, because he has not been rehabilitated.

The prosecutor’s office can rehabilitate someone as a victim of political repression. But in our case, it refuses. It says there was no political repression. An appeal against the refusal is impossible—the court does not interfere with the discretionary powers of the prosecutor’s office. It’s also impossible to review the verdict under the Code of Criminal Procedure. The Moscow City Court believes that Shakhet’s grandfather was executed for political reasons. Therefore, it refuses to accept appeals and sends us back to the prosecutor’s office.

Political repressions are a difficult topic for society. And the figure of Stalin is complicated. He was the leader of the country that won the Second World War. Under him, the USSR became a global, industrial power. But the executions for a brick, the camps for a few ears of grain, the forced deportations of entire peoples—in my eyes, these cancel out all his achievements. But, it seems, I’m in the minority. According to a sociological poll, 70% of Russians view Stalin’s role positively. Which means that even while acknowledging the fact of senseless terror, the majority prefer not to notice it. It is, after all, more pleasant to remember the positive than the tragic.

Judges don’t come from a vacuum. They come from society. So I understood that the fight for access to documents and for the opportunity to review an unjust verdict would be a long one. I also understood that appealing to logic and reason would be pointless. I needed proof that when the law was passed, something else was intended. And that proof could be in the archives. That’s what I was looking for.

When it became clear I wouldn’t be able to take pictures, I pulled out my laptop and started taking notes. After five days, I was finally done with the first batch of folders. In the archive, you can’t check out more than a certain number of pages at once. So I split my archival appetite into two sittings.

On the fifth day, with a sense of relief, I returned the first stack and ordered the second. I came back three days later. But the folders hadn’t arrived.

“So when will they be available?” I asked the archive employee, disappointed.

“We cannot release the documents. They contain personal data: people’s addresses and phone numbers.”

“But the law on personal data states that it does not apply to archival documents.”

“Call the director.”

After a short and polite argument, the director gave a second reason for the refusal. Personal privacy.

“And what is there in terms of personal privacy?” I inquired of the director.

“Addresses and phone numbers.”

“But that information isn’t a personal secret. It’s personal data.”

Tired of arguing, the director said, “We cannot give you the documents. It’s written in our instructions.”

“But the folders I studied earlier contained people’s addresses and home phone numbers,” I almost blurted out. But I caught myself in time. Who knows, they might block access to those as well.

Alright, we’ll manage without those documents.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court had requested the case file on the denial of access to the criminal case from the Golovinsky District Court. Fingers crossed!

Episode 4. “On the Eve of the Supreme Court Hearing”

“Cowardice and judicial conformity—two reasons why I didn’t continue the two-year internship to become a judge. Judges are afraid to take risks and make decisions that, while they may believe them to be correct, are unusual or new. They are afraid ‘just in case’ such decisions won’t hold up in a higher court. So it’s easier to deny, in the hope that a higher court will summon the courage and make it right.”

Tall and thin, he had been the brightest student at the law faculty of the Central European University. He analyzed, compared, and generalized like a god. His academically sterile written works made you yawn, but at the same time, they impressed with their philosophical depth, provided you had first fueled up on a liter of coffee so as not to fall asleep on the first page.

If I hadn’t been talking to an Austrian, I would have thought I was talking to a fellow countryman.

But Russia and Austria have more in common than I thought. Many of “Memorial’s” cases shouldn’t even make it to court—they are so clear-cut. For example, when a person is abducted and then there is no proper investigation into their disappearance. It’s all so clear that when the case reaches the European Court, even the Russian government says that a lot of lawyers’ time shouldn’t have been spent working on the case. The case is factually and legally simple—the violations are obvious.

Or take, for instance, our Shakhet case concerning access to the archival documents of a non-rehabilitated person. The Law on Rehabilitation grants the right to access the documents of rehabilitated persons, bypassing the requirements of the Law on Archives. The Law on Archives prohibits the release of documents containing personal secrets for 75 years.

The Law on Rehabilitation provides a privilege for the relatives of rehabilitated persons in accessing archives. This makes sense: if the state has rehabilitated someone, it has admitted that it unlawfully repressed the person for political motives.

But our courts interpret this privilege as if it prohibits access to the files of non-rehabilitated persons. It turns out that the documents of non-rehabilitated persons are more secret than materials containing state secrets. While there is hope that the latter will one day be declassified, the dossiers of the non-rehabilitated are, in the opinion of the courts, under a permanent seal of secrecy. When I explained this to the judges, they seemed to understand the absurdity of the refusal and nodded in agreement. But they upheld1 the refusal.

For the entire year I’ve been handling this case, one question has bothered me: which court will have the judicial courage to finally allow access to 80-year-old archives?

We were preparing the case for the Constitutional Court. But unexpectedly, Judge O. V. Nikolaeva of the Supreme Court decided that “the arguments of G. O. Shakhet’s cassation appeal merit attention, in connection with which the cassation appeal and the case file are to be transferred for consideration in a court session of the cassation instance.”

Tomorrow, July 5, 2019, we will assess the courage of the Supreme Court. You are welcome to come as well.

Episode 5 and Final. “The Supreme Court and After”

“My colleagues misinterpreted the law. Therefore, we support the arguments of the cassation appeal. We ask the court to grant the appeal and send the case back for a new trial,” the cultured voice of the representative from the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) rang out like a thunderclap. This surprise was so unexpected that I nudged my partner at the table, lawyer Anna Fomina from “Team 29,” as if to say, “Look at what’s happening.”

An interesting turn of events, I thought. Even our opponent—the MVD—agrees that we are right. Yet for a year and a half, the Moscow courts had insisted that we were wrong.

For a year and a half, we have been fighting for access to the case file of Pavel Zabotin, the grandfather of actor Georgy Shakhet, who was executed by firing squad during the Stalinist repressions. The MVD, and following it, courts at three levels, had denied our requests. They said that grandfather Zabotin was not rehabilitated, and therefore, access to the documents was closed forever. The courts based their reasoning on a reference to the Tripartite Provision2. However, back in 2016, the Supreme Court had ruled that the Tripartite Provision does not apply to issues of access to the files of non-rehabilitated persons.

Georgy Shakhet

When, at the hearing on July 5, 2019, even the MVD supported the appeal, we knew that the court would rule in our favor. The court went even further than we expected—not only did it overturn the decisions of the lower courts, but it also decided not to send the case back for a new trial. It ordered the MVD to grant access to the materials.

In its decision of August 5, the Supreme Court stated that the issue of access to the files of non-rehabilitated persons is governed only by the Law on Archives, not the Tripartite Provision. The Law on Archives allows access to materials containing personal and family secrets after 75 years. The presence of a personal secret, by the way, is always presumed by archives in practice.

The court made another important remark. It indicated that the secrecy of investigation and judicial proceedings does not extend to the requested documents:

“The reference by the court of first instance to paragraph 2 of the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation ‘On the Approval of the List of Information of a Confidential Nature,’ which establishes that information constituting the secret of investigation and judicial proceedings is classified as confidential information, is unfounded, taking into account the circumstances set forth above, as well as the age of the documents (more than 75 years) with which the administrative plaintiff requested to familiarize himself, and the absence of information that the materials of this criminal case constitute a state secret.”

The court, however, did not develop this logic further and did not explain when investigative and judicial documents lose their “secrecy” and become archival. About five years ago, I tried to access documents from a court archive—only parties to the proceedings are allowed to see them. In doing so, they cite the Civil Procedure Code. That is, the Law on Archives apparently does not yet apply to these documents.

Yesterday, we went to the archive to finally examine the long-awaited case file. The nice lady from the MVD archive even thanked us for winning the case. She said it had pained her to deny access, but internal instructions and the Tripartite Provision had obliged her to. Now she plans to raise the issue of granting access with her superiors.

Two dilapidated volumes from the distant years of 1932–1933, concerning the accusation of 23 people. For Shakhet’s grandfather, there are:

• a personal confession;

• testimony from other people involved in the case;

• a warrant for a search and arrest at his apartment (there is no search protocol);

• protocols of face-to-face confrontations;

• a personal file with not a single page in it;

• a 14-page indictment.

But there is no verdict. The “troikas” did not issue verdicts with a detailed analysis of arguments and evidence. They simply “approved” the indictments, sometimes rubber-stamping up to 500 verdicts a day. Therefore, the case file contains only an extract from the protocol of the meeting of the OGPU (United State Political Directorate) “troika”: “Execute Pavel Fyodorovich Zabotin by firing squad. Confiscate his property.”

No personal belongings of Shakhet’s grandfather were found in the file. Nor is there a list of confiscated property, although everything was confiscated, down to the children’s things.

“It suddenly felt empty,” my client said. “We fought for this case file for a year and a half, and somehow the charges against Zabotin haven’t become much clearer.”

The charges didn’t become any clearer to me either—the indictment does not list evidence but merely states the investigators’ version. The rest will still have to be sorted out. But the main thing is that we broke through the veil of secrecy and gained access to the files of a non-rehabilitated person. And that nice lady from the archive said that we were the first to succeed.

I hope our victory helps not only us.

Marina Agaltsova (photo: 7x7-journal.ru)

Published in the original language on the website of the Memorial HRC on 06.9.2019

Photo © Vlad Dokshin, “Novaya Gazeta”

Previous publications:

• “Enemy of the People,” Executed on the Basis of a Secret Instruction

• An Immovable Object Meets a Cassation Appeal

1 To cause a resolution, decision, ruling, law, etc., to enter into force (professional jargon of lawyers). — Translator’s note.

2 The Tripartite Provision of the FSB, the Ministry of Culture, and the MVD is a by-law to the “Law on Archives,” according to which only biographical data on non-rehabilitated persons began to be released, but access to the case files themselves was not granted. — Translator’s note.