On the night of September 3–4, 1985, in a punishment cell of the VS-389/36 special-regime camp in the village of Kuchino, Chusovskoy District, Perm Oblast, the 47-year-old poet and human rights defender Vasyl Stus passed away. There are several versions as to why this happened. But I am certain...

At that time, I was in cell 20 of the same barrack, so I consider it my civic and human duty to testify again and again, before new people, about the circumstances and causes of his death.

Since 1995, the buildings of this camp have housed the now world-famous “Perm-36” Museum of the History of Political Repressions and Totalitarianism. The last time I visited was on July 30-31, 2011.

The barrack where Vasyl Stus spent his final years, as it appears today. The first window from the left is the punishment cell where the poet spent his last days. Photo by Vasyl Ovsienko

The history of this last GULAG reserve is short. From March 1, 1980, to December 8, 1987, only 56 prisoners passed through it. On average, about 30 of us were held here at any one time.

During these 7 years, 8 prisoners died here, including members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group Oleksa Tykhy (Jan. 27, 1927 – May 5, 1984), Yuriy Lytvyn (Nov. 26, 1934 – Sept. 5, 1984), Valeriy Marchenko (Sept. 16, 1947 – Oct. 7, 1984), and Vasyl Stus (Jan. 7, 1938 – Sept. 4, 1985). Actually, only Stus died directly in this barrack; the other three died in prison hospitals.

At various times and in various cells here, in addition to those already mentioned, the following UHG members were incarcerated: Danylo Shumuk, Bohdan Rebryk, Oles Berdnyk, Ivan Kandyba, Vitaliy Kalynychenko, Yuriy Lytvyn, Mykhailo Horyn, Valeriy Marchenko, Ivan Sokulsky, Petro Ruban, Mykola Horbal, and its foreign members, the Estonian Mart Niklus and the Lithuanian Viktoras Petkus, who joined the UHG in its darkest hour—in 1982.

I also spent 6 years of my life here.

The original sign of the last political zone of the USSR, which has miraculously survived. Photo by Vasyl Ovsienko

Nearby, on the strict-regime block, were the Head of the Group, Mykola Rudenko, and a founding member, Myroslav Marynovych. Never and nowhere have so many of us gathered, except perhaps at the ceremonial meetings for the 20th, 25th, and 30th anniversaries of the Group.

Also imprisoned here were Ukrainians Ivan Hel, Vasyl Kurylo, Semen Skalych (Pokutnyk), Hryhoriy Prykhodko, Mykola Yevgrafov, and Oleksiy Murzhenko. As in every political concentration camp, Ukrainians made up the majority of its “contingent.”

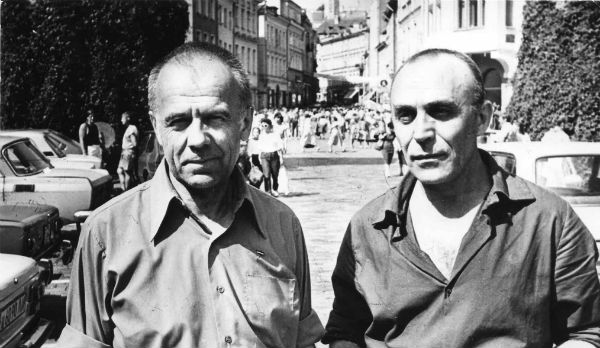

Fresh from Kuchino. Former political prisoners, Estonian Mart Niklus (left) and Hryhoriy Prykhodko, shortly after their release

In this veritable “international,” many years were spent by the Lithuanian Balys Gajauskas, the Estonians Enn Tarto and Mart Niklus, the Latvian Gunārs Astra, the Armenians Azat Arshakyan and Ashot Navasardyan, and the Russians Yury Fyodorov and Leonid Borodin. Most of these men were well-known human rights defenders and leaders of national liberation movements, and upon their release, they became politicians and public figures. But for the Soviet authorities, they were particularly dangerous recidivists.

In fact, this was not a camp, but a prison with an extremely harsh regime. While in criminal camps recidivists were taken to work in the workshops of the industrial zone, we worked in our cells, across the corridor.

We were allowed one hour of exercise per day in a courtyard measuring 2 by 3 meters, lined with sheet metal, covered with barbed wire from above, and with a guard on a platform. From our cells, we could only see a fence 5 meters from the window and a strip of sky. There were seven types of fences, including wires with live current. The perimeter of the forbidden zone was 21 meters.

A few dozen political prisoners were guarded better than thousands of criminals

Our food cost 24 - 25 rubles a month; the water was rusty and foul-smelling. We were shaven-headed, and all our clothes were made of striped fabric. We were entitled to one visit a year, one parcel of up to 5 kg a year after half the term had been served, and they tried to deprive us even of those. Some of us went for years without seeing anyone but our cellmates and the guards.

The work involved screwing a small part, into which a light bulb fits, onto the cord of an electric iron. The work was not heavy, but there was a lot of it: failure to meet the quota, like any other violation of the regime, was punished with the punishment cell, denial of visits, parcels, or access to the commissary (where we were allowed to buy an extra 4 - 6 rubles worth of products each month).

“Malicious violators of the regime” were punished with a year’s imprisonment in a one-man cell, or a transfer to prison for three years. Under Gendarme-in-Chief Andropov, in 1983, Article 183-3 was introduced into the Criminal Code, under which systematic violations of the regime were punished with an additional five years of imprisonment—this time in a criminal camp. So, the prospect of life imprisonment loomed, and especially—swift reprisal at the hands of criminals.

However, the most difficult thing to endure was the psychological pressure. If in Stalin’s time, when entire categories of the population deemed unfit for building communism were exterminated, the authorities were no longer interested in a person cast out to be ground into camp dust, in our time, a court sentence was not final.

In our time, it was rare for someone to end up in political camps for “nothing.” These were active people who, upon release, could rise up again. Therefore, the authorities closely monitored each one, determined the significance of the individual and their potential capabilities—and treated them accordingly. It was a kind of examination: they studied the tendency of development (or decline) of this or that individual and took preventive measures to ensure that they would not grow into a greater danger to the state.

From this point of view, the Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus indeed posed a particular danger to the Russian communist empire, which disguised itself as the USSR.

A monument to Vasyl Stus in the village of Rakhnivka in the Vinnytsia region, where he was born. Sculptor: Borys Dovhan. Photo by Vasyl Ovsienko

Stus, along with other human rights defenders, did indeed undermine the communist totalitarian regime, which hypocritically called itself Soviet power. And that empire did fall—having exhausted its economic capabilities, unable to withstand the military confrontation with the West, and having suffered an ideological collapse.

We fought on that front—the ideological one—and we won. I am not inclined to exaggerate our role in this fall: recently, Tomas Venclova, the leader of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group, visited Kyiv. He said that the dissidents were the mouse without which the grandfather, grandmother, granddaughter, the dog Zhuchka, and the cat Murka would not have been able to pull up the turnip...

Having served 5 years of imprisonment in Mordovia and 3 years of exile in the Magadan region, Vasyl Stus was arrested for a second time on May 14, 1980, during the “Olympic roundup”: Moscow and Kyiv, where part of the games were to be held, were being cleansed of undesirable elements, including the remaining dissidents who had gathered in the Helsinki Groups.

After his first imprisonment, Stus managed to stay in Kyiv for only 8 months. (The joke at the time was that there were three types of dissidents: pre-sidents, sidents, and ex-sidents—who were also pre-sidents again).

Stus repeatedly wrote from exile, starting in October 1977, about his readiness to join the Group, despite his somewhat critical attitude toward it. However, the Kyiv members cautiously refrained from putting his name on the Group’s documents. But when Stus returned to Kyiv in August 1979, no one could hold him back anymore: even the 75-year-old Oksana Yakivna Meshko, who had so far survived, looked up to his figure from below.

“In Kyiv, I learned that people close to the Helsinki Group were being repressed in the most brutal manner. This was, at least, how Ovsiienko, Horbal, and Lytvyn were tried, and how later they dealt with Chornovil and Rozumny. I did not want such a Kyiv. Seeing that the Group was in effect left to fend for itself, I joined it, because I simply could not do otherwise. When one’s life is taken—I have no need for crumbs...

Psychologically, I understood that the prison gate had already opened for me, that in a matter of days it would close behind me—and close for a long time. But what was I to do? Ukrainians are not allowed to go abroad, and I had little desire to go—to that foreign land: for who here, in Great Ukraine, would become the throat of outrage and protest? This is fate, and one does not choose one’s fate. So one accepts it—whatever it may be. And when one does not accept it, then it chooses us by force... (“From a Camp Notebook,” entry 6. // V. Stus. Tvoru v 6 t. 9 kn. [Works in 6 vols., 9 books]. - Vol. 4. - Lviv: Prosvita, 1994. - p. 493).

“But I was not going to bow my head, no matter what. Behind me stood Ukraine, my oppressed people, for whose honor I must stand until my demise.” (Ibid., entry 4, p. 491).

With his family shortly before his final imprisonment

With a standard sentence of 10 years in a special-regime camp, 5 years of exile, and the “honorable” title of “particularly dangerous recidivist,” Vasyl Stus arrived in Kuchino in November 1980. Here, he was watched with particular care. From the Urals, he managed to send only a few poems in letters to his wife.

In the special-regime block, one was allowed to write one letter a month. You would polish it and polish it—and still they would find “prohibited information,” “coded language in the text,” or simply—the letter was “suspicious in content.” And they would confiscate it. Or they would send the letter to Kyiv for translation, and then decide whether to send it on. They would suggest: “Write in Russian—it will get there faster.” But how can one write to one’s wife, mother, or child in a foreign language?

One could receive letters from anyone, but in reality, they only gave us some letters from relatives. In the final weeks of his life, Vasyl received a telegram from his wife about the birth of their grandson, Yaroslav (May 18, 1985). Major Snyadovsky summoned Stus to his office, congratulated him, and read a part of the telegram, but did not hand it over: prohibited information. This greatly angered Stus.

Searches. They were conducted two or three times a month, but there were periods when a prisoner could be searched several times a day—just to humiliate him. One was allowed to keep 5 books, brochures, and journals, combined, in the cell. The rest—out to the storage room.

And everyone subscribes to journals and newspapers, and tries to work on something, even if it’s just learning a foreign language. For that you already need a dictionary and a textbook. But the regime is relentless: excess books are thrown out into the corridor.

We would take slips of paper with foreign words to work to study them (Stus was fluent in German and English, read in all Slavic languages, and was studying French with the help of the Estonian Mart Niklus). The slips of paper were taken away.

Mykhailo Horyn in his “home” cell No. 17. Photo by Vasyl Ovsienko

When they took you out to work, they would lead you into their “duty room”—and make you strip naked. They would feel every seam, look into every fold of your body. I can still hear his pained voice: “They handle you like a chicken...” Such a remark was enough to get you thrown into the punishment cell.

They were especially vigilant when a visit was approaching. If the KGB decided not to grant a visit, depriving you of it was a technical matter: the guards were given the task of finding a violation of the regime. Talking through the small window with the neighboring cell. Failing to meet the production quota. Announcing an illegal hunger strike.

The head of the regime, Major Fyodorov, personally discovered dust on a shelf. The same Fyodorov once punished Balys Gajauskas because “in conversation he was not candid.” And if you had candidly said what you thought of him, you would have been an even bigger violator of the regime.

Stus had only one visit in Kuchino. When they were taking him to the second one, he could not stand the humiliating search procedure and returned to his cell.

They began to “press” Stus particularly hard from 1983 onwards. On his birthday, which is Christmas Day, they conducted a search. They took his manuscripts. Stus called for the duty officer, Major Galedin, to return the manuscripts or draw up a report on their confiscation.

- And who took them?

- That new major, I don’t know his name. That Tatar.

A report was drawn up that Stus had insulted the national dignity of Major Gatin. Although he really was a distinctly Tatar-looking man, he had probably already signed up for the superior race—the “great Russian people.” Stus was thrown into the punishment cell. At the same time, the Estonian Mart Niklus was also thrown into the punishment cell:

- Stus, where are you?

- In some kind of gas chamber named after Lenin-Stalin! And Gatin-the-Tatar!

A loudspeaker was turned on in the corridor.

Later, while at work, vigorously tightening screws with a mechanical screwdriver, Vasyl improvised: “For Lenin, for Stalin! For Gatin-the-Tatar! For Yuri Andropov! For Vanka Davykhlopov! And very slowly for Kostya, for Chernenko. Because how can you fit him into a rhyme?”

I once heard Stus talking to KGB officer Vladimir Ivanovich Chentsov:

- You say you’ve put my manuscripts in a storage depot outside the zone. But I know that what you want is for nothing of me to remain when I die... I am no longer writing my own work, only translating. So at least give me the opportunity to finish something...

It was easier for those who could stop writing in captivity. An artist, as my cellmate Yuriy Lytvyn used to say, is like a woman: if he has a creative idea, he must give birth to a work. And just as it is hard for a mother to see her newborn child destroyed, so it is for an artist when his work is destroyed. And even more so when that child is torn from the womb prematurely and trampled by the dirty boots of the guards...

In February 1983, Stus was thrown into solitary confinement for a year. When he came out, he and I were put together in cell 18 for about a month and a half.

I read his handmade thick notebook in a blue cover (without a title) with several dozen poems written in free verse, and a graph-paper notebook with translations of 11 of Rilke’s elegies. At that time, I was in poor physical condition and did not manage to learn a single poem. And I didn’t expect that we would be separated so quickly.

In letters dated September 12 and December 1983, Stus calls that collection “Bird of the Soul” and writes that it contains about 40 poems (Vol. 6, bk. 1, pp. 444 and 449), and in a letter dated February 1, 1985, he writes about 100 poems. “And 50 more are maturing in draft form” (p. 483). And he also writes: “...a collection like ‘Passion for the Fatherland’ is burning in my soul” (p. 479, letter from November-December 1984).

“I translated Rilke’s ‘Elegies’—that’s about 900 lines of extremely difficult poetic text” (p. 444, letter of Sept. 12, 1983).

That “Bird” did not fly out from behind the bars. And let us not console ourselves with the sweet fairytale that manuscripts do not burn.

Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska wrote: “...the tree of Stus’s poetry—with its crown cut off near the top...” (Vol. 1, p. 28).

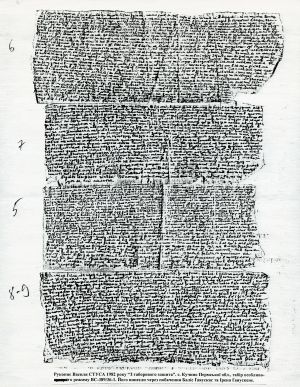

This is what the text written by Stus, which later became known as “From a Camp Notebook,” looked like.

This is another crime of Russian imperialism against Ukrainian culture. Of his five Kuchino years, what remains are 45 letters, a few poems, and a text that has been titled in publications “From a Camp Notebook.” Sometime in early 1983, his cellmate Balys Gajauskas passed these 16 scraps of finely written condenser paper to his wife, Irena Gajauskienė, during a visit, along with his own manuscripts. In book form, this amounts to 12 pages of text, but their explosive power was so great that it destroyed Vasyl himself.

I believe that one of the reasons for his destruction was the appearance of this text in the West.

The second reason was the petition to nominate his work for the 1986 Nobel Prize. Vasyl Stus’s poems were published in several languages. The world saw the level of talent of the Ukrainian poet not through the prism of dissidence, but as an artistic phenomenon.

In my earlier publications, it was stated that Stus’s work was supposedly nominated for the Nobel Prize by Heinrich Böll, the 1972 laureate and president of International PEN (1971-76, he died on July 16, 1985). H. Böll did indeed speak out in defense of Stus at least twice. For example, on December 24, 1984, he, along with the German writers Siegfried Lenz and Hans Werner Richter, sent a telegram to the then-General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, Konstantin Chernenko, about the alarming state of V. Stus’s health. There was no reply.

On January 10, 1985, H. Böll gave an interview to German radio about V. Stus. It was reprinted in the press. But no document of nomination for the Nobel Prize exists; no mention of it has been found anywhere.

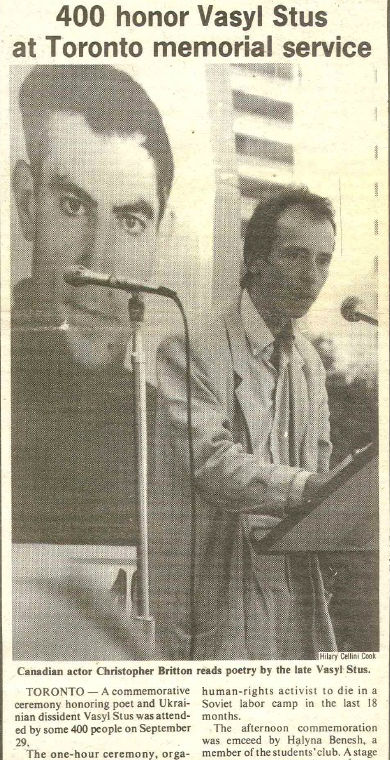

The historian and journalist Vakhtang Kipiani, in his publication “Stus and Nobel: Demystifying the Myth,” writes: “In the newspaper ‘Ameryka’ of December 17, 1985 (note—this is three months after Stus is no longer alive), we find information that at the end of ’84, an ‘International Committee for the Awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Vasyl Stus in 1986’ was created in Toronto.”

The Committee included prominent scholars and figures from the Ukrainian diaspora, and respected individuals from many countries around the world. The chairman of the committee was Dr. Yaroslav Rudnyckyj. The committee distributed over a hundred letters with requests to send letters of recommendation to the Nobel Committee and organized translations of Stus’s works, but it was counting on the year 1986.

Posthumous tribute to Vasyl Stus in Toronto. The attempt to make him a Nobel laureate was made too late and was unsuccessful.

At that time, the Kremlin had enough trouble with Nobel laureates Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1970), whom it had to throw out of the country (February 13, 1974), and Andrei Sakharov (1975), who was deported to Gorky at the beginning of the Afghan War (January 22, 1980) and held there under house arrest.

The Kremlin knew that the Nobel Prize, according to its statute, is awarded only to the living; it is not awarded posthumously. The Kremlin could not allow a Nobel laureate, and a Ukrainian one at that, to appear behind bars (as this would have raised the “Ukrainian cause” to an unprecedented height).

In 1936, Adolf Hitler found himself in a similar situation. The Nobel Prize was awarded to the German journalist Carl von Ossietzky. But he was in a concentration camp. Hitler ordered his release. But while the bureaucratic machine was turning, the laureate died in captivity.

Moscow, however, resolved the issue of the Ukrainian candidate for the Nobel Prize according to Stalin’s testament: “No man, no problem.”

Stus’s friends—Mykhailo Horyn, Paruyr Hayrikyan, and Vasyl Ovsienko—at his grave at the Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv.

And this happened during the time of Gorbachev, who took the Kremlin “throne” in April 1985.

Gorbachev’s defenders will say that he, most likely, had not even heard of Stus. But I am certain that our cases were considered and decided at the highest level. At that time, there were about as many particularly dangerous political recidivists as there were members of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee in the Kremlin.

Gorbachev, you see, initiated “perestroika,” without releasing from captivity what would seem to be his closest allies—political prisoners, as is done everywhere. But he held us even in 1988, some even in 1989, and having become a Nobel Peace Prize laureate himself (1990), began a new roundup of political prisoners. He pardoned us, you see. That is, he considered us criminals to whom he showed mercy.

Rehabilitation came only in 1991...

I am certain that the administration of camp VS-389/36 received an order from the Kremlin to eliminate Vasyl Stus by any means necessary.

How did it happen? In prison, you see little, but you can determine what is happening by the sounds.

In the summer of 1985, Vasyl Stus only briefly came out of the punishment cells and was in cell No. 12 with Leonid Borodin (a Russian writer, now the chief editor of the journal “Moskva”). The cell is small; you can stretch out your arms and touch the walls. A double bunk, two stools, one nightstand for two, and a slop bucket. One is only allowed to be on the bunks for 8 hours—from lights-out to reveille. To sit on them at any other time is a violation of the regime.

One night, a soldier on the watchtower was singing loudly. Borodin got up, pressed the call button, summoned the guard, and asked him to call the soldier and tell him not to disturb their sleep.

The next day, it turned out that it was Stus who had woken up the whole prison—and he was thrown into the punishment cell for 15 days. Borodin went to argue with the camp chief, Major Zhuravkov—but he said that he trusted his subordinates. He already had another task: to destroy Stus.

A few days after the punishment cell, on August 27, a new misfortune. Stus took a book, placed it on the upper bunk, and read it, leaning on the bunk with his elbow. A guard, Warrant Officer Rudenko, looked through the peephole: “Stus, you are violating the bed-making regulations!” Stus assumed another, permitted, posture. But the duty officer, Senior Lieutenant Saburov, the guard Rudenko, and another guard drew up a report that Stus was lying on his bunk in his outer clothing during working hours and had entered into an argument with the controller when reprimanded. 15 days in the punishment cell.

As he was leaving the cell, Stus told Borodin that he was declaring a hunger strike. “What kind?” - “To the end.”

In 1983, there was a time when Stus went on a hunger strike for 18 days. He told me later: “How disgusting it is to come off a hunger strike, having achieved nothing at all. I will not do that again.” He was a man of his word.

The punishment cells are located in the northern part of the barrack, in a small transverse corridor. Stus was held in the 3rd punishment cell, which is on the corner, closest to the guardhouse. No sounds reached us from there.

The punishment cell where Vasyl Stus was held in his last days. Photo by Vasyl Ovsienko

On September 2, we could hear from our work cells that Stus was being taken to some superior. On his way back, he deliberately repeated loudly in the corridor: “I will punish you, I will punish you... Go on, destroy me, you Gestapo men!” This was his way of letting us know that he was being threatened with new punishment.

In the evening, the Estonian Enn Tarto would collect the finished products (cords for irons) from the cells and distribute work for the next day. On September 3, at about 5 p.m., he heard Stus ask for Validol. The guard replied that the doctor was not available. So Enn Tarto himself told Dr. Pchelnikov, and he gave Stus Validol. So, he was having heart trouble.

In the opposite end of that corridor, across the way, Levko Lukianenko worked during the day in work cell No. 7. When he couldn't hear the guard, Levko would call out: “Vasyl, hello!” Or: “Hey!” Vasyl would respond.

But on September 4, he did not respond. Instead, at about 10 or 11 o’clock, Levko heard the authorities enter the corridor through a back entrance. He recognized the voices of the camp chief, Major Zhuravkov, the head of the regime, Major Fyodorov, and KGB officers Afanasov and Vasilenkov. They were opening doors, murmuring something quietly. And then—an unusual silence.

“Even that heathen woman wasn't laughing,” Levko recalled. He was referring to the female workshop master.

That day, a bread ration was ordered from the kitchen, as if someone were being transferred. A ration for the road was never given in Kuchino: the journey to Perm or to the hospital took only a few hours, and a ration was issued there. But that ration was forgotten about.

There was also an incident where Borodin was told to hand over Stus’s spoon. This was an attempt to plant the idea that he had ended his hunger strike.

Over the next few days, we signed up for appointments with the authorities for various reasons. Dr. Pchelnikov was not available. KGB officer Vasilenkov was not available. Major Zhuravkov was not available. The duties of the chief were being performed by Major Dolmatov, the political officer. To questions about Stus, he would answer: “We are not obligated to answer you about other prisoners. It is not your business. He is not here.”

There was still a glimmer of hope that Stus had been taken to the hospital at the Vsekhsvyatskaya station. But at the end of September, I myself was taken there. I was held alone, but I still found out that Stus had not been there. Perhaps he had been taken somewhere further?

On October 5, two KGB officers summoned me—some local one (his name sounded like Zuev or Zubov) and Vasyl Ivanovych Ilkiv, who had come from Kyiv. In my conversation with them, I named all those who had died in Kuchino, including Stus.

- Well, Stus... His heart couldn't take it. It can happen to anyone.

And right there, my heart sank...

It is entirely possible that death was caused by a heart attack. But let us consider that Stus was on a hunger strike in a cold punishment cell, wearing only trousers, a jacket, underwear, a T-shirt, socks, and slippers. No bedding is issued. Perhaps his slippers for a pillow. The daytime temperature then was unlikely to have reached 15 degrees Celsius. The sun does not shine into that punishment cell.

In the morning, in our 20th cell, Balys Gajauskas and I would see ice on the windowpanes. And Stus had nothing to cover himself with. And no energy to get warm...

Lukianenko experienced similar situations and described them in his essay “Vasyl Stus: The Last Days” (Ne dam zahynut’ Ukraini! K.: Vyd. “Sofiia,” 1994. - pp. 327 - 343). It is a psychologically authentic essay, but I must caution that Lukianenko partly models Stus’s behavior and the events surrounding him. After all, he was not nearby.

The camp administration had to inform his widow, Valentyna Popeliukh, of her husband’s death. She ordered a zinc-lined coffin and set off on the journey with her sister Oleksandra and a friend, Ryta Dovhan. At the airport, KGB officers categorically advised them not to take the coffin, as the body would not be released to them.

One must know that the most humane Soviet law in the world did not permit the taking or reburial of the body of a deceased prisoner until his term of imprisonment was over. So the dead remained under arrest.

Their son Dmytro, who was serving in the army at the time, came from Moscow. They arrived on September 7, and Major Dolmatov told them: “Well then, let’s go to the cemetery.” And he brought them to a freshly covered grave in the village of Borisovo, about three kilometers from the zone.

At the first resting place in the cemetery of the village of Borisovo, Chusovskoy District, Perm Oblast. The poet’s son, Dmytro Stus; former political prisoners Viktor Pestov, Mart Niklus, and Vasyl Ovsienko. Photo by Vakhtang Kipiani

...On February 24, 1989, the 46-year-old Major Dolmatov was laid to rest next to Stus, just a few graves away. And Major Zhuravkov died about 10 days after Stus. The younger Zhuravkov, a lieutenant-investigator, drowned in the Chusovaya River in the summer of 1987. All this raises serious doubts as to whether Stus’s death was really the result of a heart attack.

Somewhere in one of the punishment cells (Balys Gajauskas says it was the 6th), Boris Romashov, a native of Gorky, was being held at the time. He was a murderer who had “taken a political platform.” He had been imprisoned for the umpteenth time for primitive anti-Soviet slogans with which he had defaced his passport and military ID and thrown them into the yard of the military enlistment office.

Although Romashov said he had a certificate for psychopathy, he was still given 9 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile. He had had a conflict with Stus: he had threatened him in the 13th work cell with a mechanical screwdriver. Stus also raised a screwdriver—and the other man did not dare to strike. Both were put in for 5 days. And a year before his release, Romashov tried to kill Balys Gajauskas, striking him several times in the head and chest with a mechanical screwdriver. Balys fell under a table, so the blade’s blow came at an angle, missing his heart. For this act, Romashov was punished only with the punishment cell, but a KGB officer would bring him tea there.

At our meeting in Kuchino in October 2000, Gajauskas suggested that Romashov might have been sent to kill Stus...

But in October 1985, Enn Tarto said that Romashov had supposedly heard Stus groan on the evening of September 3, during “lights-out”: “They’ve killed me, the bastards...”

A few months later, I had the opportunity to ask Romashov if he confirmed hearing Vasyl’s groan. - “I don’t want to talk about it.”

Or it could have been like this. During “lights-out,” the guard tells the man in the punishment cell: “Hold the bunk.” Because they are held up by a pin. From the corridor, through a hole in the wall, the guard removes the pin—and the bunk falls down; the prisoner is supposed to lower it. Under the bunk, a stool is chained to the floor, the only place to sit. The guard could have suddenly removed the pin—and the bunk struck Stus on the head...

With hindsight, we, the prisoners, recalled and compared all the details.

We remembered that on the night of September 4-5, the boar-like roar of the guard Novitsky echoed in the corridor: “Give me the knife!” This was them already launching the story that Stus had hanged himself with a cord in the work cell.

A former guard, Ivan Kukushkin, peddled this version to me in Kuchino in 1996. But Kukushkin was no longer working with us at the time of Stus’s death. In a conversation with Kukushkin in 2001, Lukianenko refuted this version. He had clearly noted that no one had worked the second shift in his 7th work cell, where Stus was supposedly taken to work. He noticed how he left parts on the table. Nothing had been disturbed.

If Stus was on the second shift in a work cell, it was in the 8th, which is in the main corridor. For I, too, heard on the evening of the 3rd that he was demanding his boots for the work cell (in the punishment cell they keep you in slippers). I would not have heard his voice from the 7th cell, as it is around the corner, in the transverse corridor.

Through the criminal Vyacheslav Ostroglyad, they tried to launch the version of suicide in punishment cell No. 3 with a sharpened awl. But neither a cord nor an awl could have possibly gotten into the punishment cell: Stus was searched very thoroughly.

During the exhumation on November 17, 1989, we did not notice any damage to the head or neck. His face was not contorted, as is the case with someone who has been hanged. Only the nasal cartilage (the tip of his nose) had collapsed. But, in truth, the procedure took place under such tension that we were not in a state to conduct a proper examination.

Kyiv, November 19, 1989: the reburial of Vasyl Stus and his friends Yuriy Lytvyn and Oleksa Tykhy.

I do not give preference to either of my two versions: heart attack or a blow to the head from the bunk bed. The perpetrators know the secret of Vasyl Stus’s death. Some of them died soon after, and not by chance. The ones who ordered it know, and some of them are still alive. But they will not confess to the crime.

Here is the final version of a famous poem by Stus, which I have preserved in my memory. It is a death sentence for the Russian empire.

Oh, enemy, when will you be forgiven

for the death rattle and the heavy tear

of those shot, tortured, slain

in the Solovkis, the Sibirias, the Magadans?

A state of darkness, and darkness, and darkness, and darkness!

You have writhed like a serpent, ever since

unexpiated sin has shaken you

and the pangs of conscience have disfigured your spirit.

Rage on the edge of the abyss, keep your balance,

barricade all paths to yourself,

for you know well—o sinner of the universe—

one cannot flee oneself to the ends of the earth.

This madness of impulse, this torn

flight through everything—from hell to heaven,

this hanging over death, this thirst

of the corrupt to corrupt the entire white world

and to keep bludgeoning, bludgeoning the tormented victim

to wring forgiveness for your own

horrific cruelties—it is all too much,

etched on souls and on spines.

That tear will incinerate you,

and a fierce cry will sprout a hundredfold

across fields and meadows. And you will grasp

the maddened, all-destroying nature of your kind.

O ruler of your own death, fate is

all-remembering, all-hearing, all-seeing—

it will forget nothing, nor forgive.