We have previously written about how, since 2017, the Russian citizen Georgy Shakhet has been trying to access the criminal case files of his grandfather, who was executed under the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK) decree of August 7, 1932, “On the Protection of the Property of State Enterprises, Kolkhozes and Cooperatives and the Consolidation of Socialist Property”—the infamous “Law of Three Spikelets.” Shakhet, whose interests are represented in court by lawyers from the Memorial Human Rights Center together with Team 29 (an informal human rights association of lawyers and journalists), is appealing the verdict handed down by an OGPU “troika.” This article, published on the Memorial Human Rights Center website, covers the current state of the case. The following is an English translation of that material.

In December 1932, Pavel Zabotin, a 45-year-old construction engineer, was arrested and, two months later, in February 1933, executed by order of a “troika.” He has still not been rehabilitated, even though individuals executed by order of the “troikas” have long since been rehabilitated en masse as victims of political repression. For two years, Zabotin’s grandson, Georgy Shakhet, with the support of the Memorial Human Rights Center and Team 29, has been trying to gain access to the archive where his grandfather’s case file is stored. However, courts at various levels have denied Shakhet access, citing the fact that Zabotin has not been rehabilitated and, therefore, access to his case is prohibited by law. On March 12, a court hearing was held at the Moscow City Court, where it suddenly became clear: if the prosecutor’s office says there are no grounds for rehabilitation, then the court sees no grounds for it either. This means that today there is no possibility of reviewing the mistakes of the past—the verdicts handed down by the “troikas.”

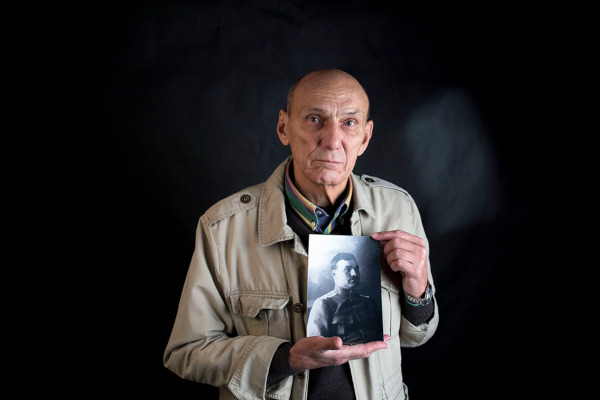

Georgy Shakhet (Photo: Vlad Dokshin, “Novaya Gazeta”)

Zabotin, who worked as the head of the construction sector for the Leningrad Food Supply Administration, was accused of submitting fictitious invoices for over 11,000 rubles (approximately 11,000 hryvnias – PL), and of stealing, along with others, 20,000 bricks and 20 crates of glass with a total value of 22,400 rubles.

The Memorial Human Rights Center, which Shakhet approached for help, had only two options for appealing the 1933 verdict against Zabotin: appeal to the prosecutor’s office or file a cassation appeal with the Moscow City Court. Through the prosecutor’s office, a person can be rehabilitated if they were a victim of political repression. A cassation appeal is used to challenge a verdict if there was no political repression or if the person was tried for a combination of crimes (for example, one politically motivated, the other not).

• In October 2018, the prosecutor’s office reviewed a petition from Memorial HRC lawyer Marina Agaltsova for Zabotin’s rehabilitation and denied it. The prosecutor’s office stated that the theft of glass and bricks was a common crime.

• On December 10, the lawyer appealed the prosecutor’s refusal in the Tagansky Court. Agaltsova insisted that there were all the signs of a politically motivated execution—the man was shot for GLASS! However, the Tagansky Court said it could not interfere with the prosecutor’s decision and that the defense must appeal the verdict through a cassation procedure.

• The lawyer then appealed Zabotin’s verdict to the Moscow City Court through a cassation appeal. The court confirmed that there were all the signs of political repression. On these grounds, the court stated that it would not consider the case further—the lawyer needed to go to the prosecutor’s office.

• On March 12, at the Moscow City Court, Marina Agaltsova appealed the Tagansky Court’s decision of December 10. She told the Moscow City Court: the prosecutor’s office refuses to rehabilitate, saying there is no political repression here and that the lawyers must appeal Zabotin’s verdict in cassation. We went to you—the Moscow City Court—in cassation, and you told us that there are all the signs of political repression here, so it’s impossible to appeal in cassation; we must go to the prosecutor’s office… As a result, the Moscow City Court upheld the Tagansky Court’s decision. It said it had no right to interfere with the discretionary powers of the prosecutor’s office. Thus, the Tagansky Court’s decision came into force. It will be appealed.

It turns out that in 1933, a man was convicted in secret—without a trial or investigation, without the ability to review documents, without participating in the hearing, without a lawyer, and even without the right to appeal the verdict. In theory, the law on the rehabilitation of victims of political repression provides two avenues for a court to issue a just decision today—to publicly review what was decided in secret and to correct, or not correct, the historical mistake made back then. But in practice, this law does not work. At least, not in our case.

The lawyers from Memorial and Team 29 intend to take Zabotin’s case to the Constitutional Court.