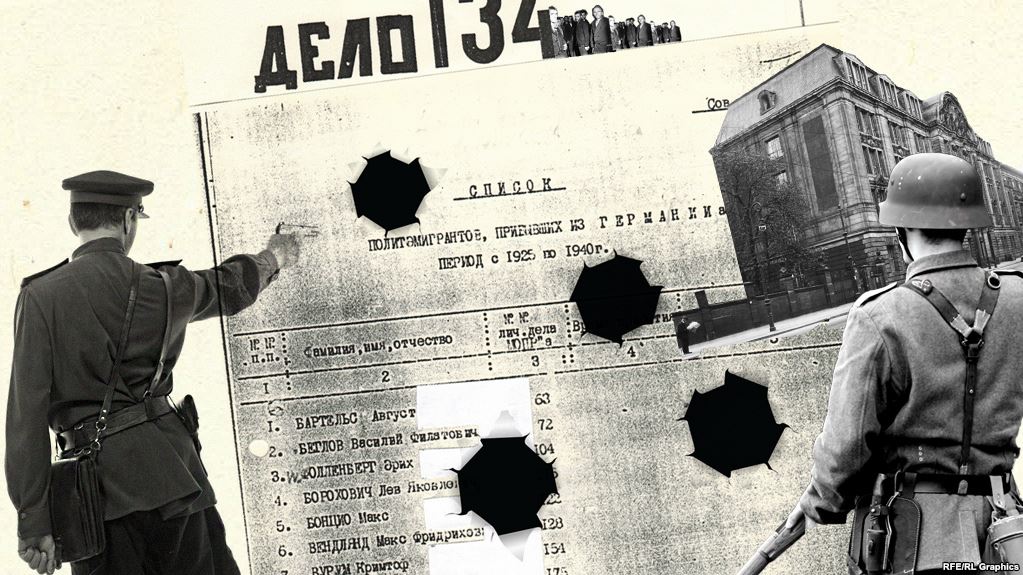

Cooperation between the Gestapo and the NKVD, a collage

Cooperation between the Gestapo and the NKVD, a collage

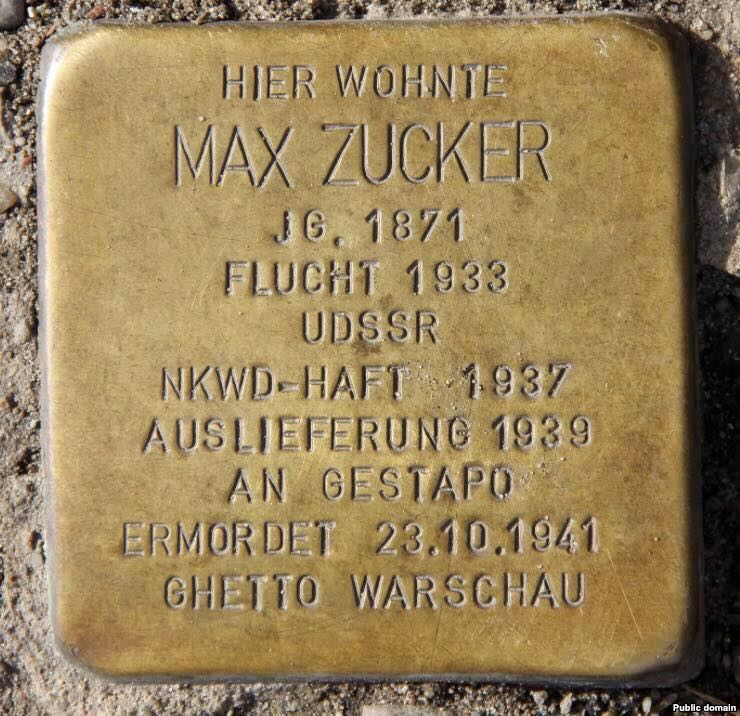

On Dernburgstrasse in Berlin, among other "stumbling stones" that remind passersby of the victims of Nazism, there is a brass plaque engraved with several dates. It is placed on the site where the house of businessman Max Zucker stood before the war. After Hitler came to power, he decided to emigrate from Germany and moved to be with his son, who lived in the USSR. The decision proved fatal. In 1937, Max Zucker was arrested by the NKVD on charges of espionage, and in 1939, after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, he was deported to Nazi Germany. Gestapo officers were waiting for him at the border. As a Jew and a native of Poland, Max Zucker was sent to the Warsaw Ghetto. On October 23, 1941, he was beaten to death by SS men on a ghetto street.

Documents recently discovered in the archives of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, opened to researchers after the 2014 revolution, show how the NKVD handed over refugees from Germany, who had hoped to find salvation from Hitler in the USSR, to the Gestapo.

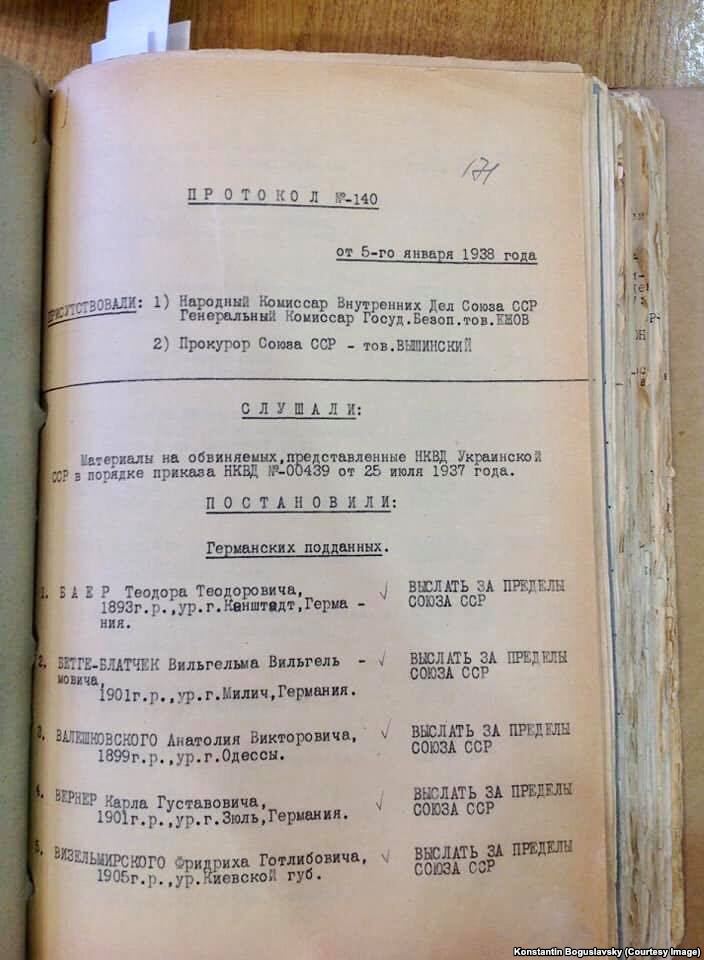

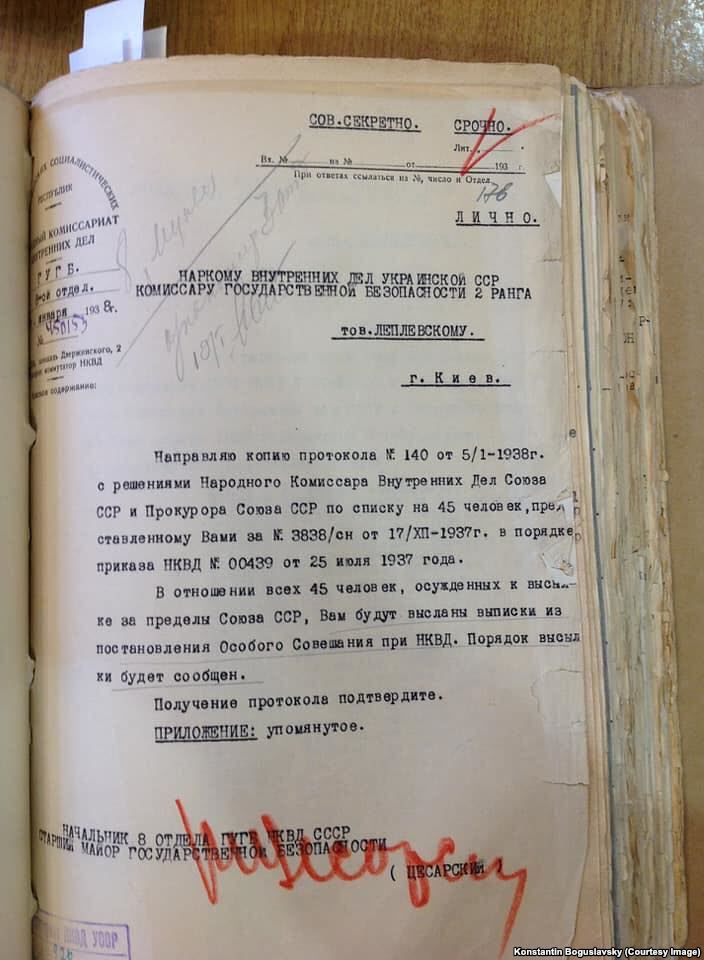

A protocol dated January 5, 1938, is signed by Narkom Yezhov and Prosecutor Vyshinsky. It lists the names of 45 citizens of Germany, Austria, and other countries sentenced to expulsion from the USSR. After Stalin and Hitler became allies in 1939, the extradition of refugees to the Nazis was put on a production line. Before the summer of 1941, the NKVD had transferred hundreds of people to Germany. Most were members of the German Communist Party, which Hitler had crushed. Stalin sent communists and Jews who sought salvation from Nazism in the USSR to Hitler.

Heinz Neumann, a member of the Politburo of the KPD and a Reichstag deputy, and his wife, Margarete, were expelled from Nazi Germany in 1935 and came to the USSR. In 1937, Neumann was arrested by the NKVD and executed. His wife, as a "socially dangerous element," was sentenced in 1938 to five years in the camps and sent to Karaganda. In 1940, she was deported to Germany. Margarete Buber-Neumann recounted this in her memoirs, “Under Two Dictators”:

...On the night of December 31, 1939, to January 1, 1940, the train departed. It carried away seventy broken people... We traveled on through devastated Poland towards Brest-Litovsk. On the bridge over the Bug River, officers of another European totalitarian regime—the German Gestapo—were waiting for us. Three men refused to cross that bridge: a Hungarian Jew named Bloch, a communist worker who had been convicted by the Nazis, and a German teacher whose name I have forgotten. They were dragged to the bridge by force. The fury of the Nazis, the SS men, was immediately unleashed on the Jew. We were put on a train and taken to Lublin... In Lublin, we were handed over to the Gestapo. It was then that we were able to see for ourselves that we were not just handed over to the Gestapo, but that the NKVD had also passed on to the SS the files concerning us. Thus, for example, my file indicated that I was Neumann's wife, and Neumann was one of the Germans most hated by the Nazis...

Margarete Buber-Neumann was imprisoned in the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she miraculously survived.

Ernst Fabisch (1910–1943) was a member of the youth organization of the German Communist Party. After the National Socialists came to power, he became one of the leaders of the anti-fascist resistance. An arrest warrant was issued for him by the Gestapo, but he managed to escape in 1934 to Czechoslovakia and then to the USSR. He worked on the construction of power plants in Stalinsk (Novokuznetsk) and the Moscow region. In April 1937, Ernst Fabisch was arrested by the NKVD, spent six months in Soviet prisons, and in January 1938 was deported to the German Reich. At the border, he was arrested by the Gestapo. In prison, Ernst Fabisch contracted tuberculosis and, after five years of imprisonment, was killed in the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1943.

The cooperation between the NKVD and the Gestapo began even before the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and at first, it was about deporting German citizens to their homeland: these were formal contacts to clarify the time of arrival and the number of deportees. In 1939–1940, after the signing of the pact, several so-called "conferences" between NKVD and Gestapo officers took place in Poland, which had been divided between the two allied powers. They were primarily dedicated to methods of suppressing the Polish resistance. Historian Robert Conquest indicates that four such conferences were held. Documents about these negotiations are still classified in the Soviet archives.

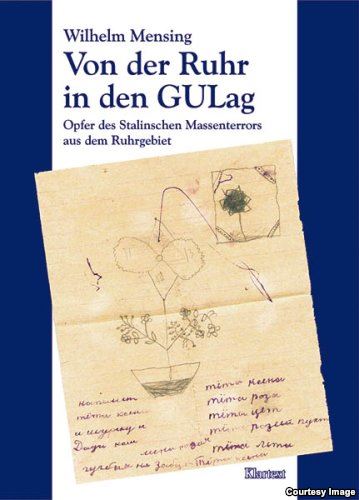

German historian Wilhelm Mensing created the website "NKVD and Gestapo," dedicated to the fates of Germans who fled Hitler and were arrested in the USSR, sent to the Gulag, executed, or handed over to the Nazis.

In his book “From the Ruhr to the Gulag,” he tells the story of German workers who fell victim to Stalin. In the early 1930s, newspapers in the Ruhr coal basin published advertisements inviting workers to the Soviet trust "Soyuzugol," promising miners fabulous wages. In 1931, miner Fritz Baltes signed a contract at the Soviet trade mission in Berlin and went to the Kalinin mine in Kizel, where he rose to the rank of foreman. On October 15, 1937, he was arrested. NKVD investigator Bliznyak immediately began to beat him. The Chekists needed to invent a conspiracy, and miner Franz Winter, who had signed the same contract at the Soviet trade mission, was chosen for the role of another German saboteur-spy. "During my interrogations, I was subjected to the most brutal torture. In the process, eight of my teeth were knocked out. Due to blows to my left ear, my eardrum ruptured, so that today I can no longer hear with that ear," he later recounted.

On January 7, 1938, a resolution of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), "On the Organization of a Show Trial in Kizel," authorized the Sverdlovsk UNKVD to hold an open show trial of "saboteurs operating in the Kizel coal basin." Baltes and Winter were sentenced to be shot, but the death penalty was later commuted to 25 years in corrective labor camps. They were sent to the Kotlas distribution camp, from where they wrote letters asking for help to the German embassy. On May 2, 1940, they were brought to Brest-Litovsk, where German border guards took them across the border into Germany. Now Winter and Baltes were in the hands of the Gestapo and were placed in Lublin prison. This is just one of the many stories told in the book “From the Ruhr to the Gulag.”

Wilhelm Mensing answered questions from Radio Liberty:

—When did you start your research? Is it connected to your family history?

—I can say exactly how it all started: it happened when I read the collection "In the Clutches of the NKVD," which first told the story of hundreds of emigrants from Germany to the USSR, especially members of the German Communist Party. In this book, I found the names of unemployed people who went to the Soviet Union in the early 1930s in the hope of finding a place for themselves and helping to build socialism. Many of them disappeared in the USSR, while others were arrested and returned to their homeland. This has no connection to my family history. I have never been a member of a socialist or communist party and did not personally know any victims of Stalin's terror. I was guided by considerations of humanity (to remember the victims, not to forget the criminals) and a desire to know the truth. But there is another reason. For a long time, I researched communist politics in Germany. In 1983, I published a study on the influence of the Communist Party on journalism, literature, and art, and in 1989, a two-volume work on the revival of the German Communist Party was released. So I was well acquainted with communist history and worldview.

—Why did you decide to write the book “From the Ruhr to the Gulag”?

—When I read the collection “In the Clutches of the NKVD,” I began to ask historians from the Ruhr whether they were willing to research the fate of emigrants from the Ruhr who went to Stalin's USSR and then returned to Hitler's Germany. All of them, without exception, replied that they were so busy with the history of the Nazi era that they had no time for it. And so I decided that I must do it myself. I cannot allow these people to be forgotten.

—Is it known for certain how many Germans were arrested in the USSR during the Great Terror and how many were deported to Germany? And by what principle were they repressed?

—I see no logic in Stalin’s repressions and I doubt that anyone understands it. The exact number is also unknown, but one can roughly establish how many people were expelled after the signing of the pact between Stalin and Hitler. On my website, 325 people are listed. I believe there were no more than 350. At the same time, about 80 citizens of Germany and Austria received permission to leave the USSR without being deported.

—What happened to the deportees?

—Most avoided arrest. The youngest were sent to serve in the Wehrmacht. Some (former) members of the Communist Party were sent to concentration camps; a few managed to survive. Almost all the Jews became victims of the Holocaust; only a few were able to leave for Great Britain, the USA, and other countries.

—Why did you decide to create a website dedicated to the collaboration between the NKVD and the Gestapo, and do you receive feedback?

—I decided to create this site after publishing “From the Ruhr to the Gulag.” It was impossible to include all the materials I had in the book, otherwise it would have become too expensive, so I decided to collect them on a special website. Later, as I began to study other aspects of Stalin’s terror, especially emigration and re-emigration, I realized that publishing names on the internet is the best way to attract the attention of everyone interested in the topic. The feedback from historians and descendants of the people I write about shows that I chose the right format.

—Are there any interesting documents on this topic in the Stasi archives? Did you try to find anything in the KGB archives?

—There are very few documents on this topic in the Stasi archives. Stalin’s repressions were a taboo subject for the SED. When re-emigrants who had suffered in the USSR were rehabilitated in the GDR in the late 1950s, it was strictly forbidden to talk about both the repressions and the rehabilitation. I have seen many documents from the RGASPI archive, service records, lists of emigrants, lists of people expelled from the party or arrested. However, many documents (particularly the Comintern papers) remain classified.

Wilhelm Mensing focuses on several tragic fates in his book. Journalist Willi Harzheim became a member of the Communist Party in 1923. In 1929, after moving from Gelsenkirchen to Berlin, he got a job at the Union of Proletarian Writers. In 1930, as part of a German delegation, he participated in the International Conference of Proletarian and Revolutionary Writers in Kharkiv. After the Nazis came to power, he emigrated to the USSR and, as a "cultural worker," was sent to Siberia. In Prokopyevsk, he worked for the newspaper "Krasny Shakhter" (Red Miner). On November 20, 1937, Willi Harzheim was arrested and shot on December 17 for "counter-revolutionary activities."

Communist Arnold Klein emigrated to the USSR in 1934. Under the party pseudonym Hans Bloch, he worked for publications of the German Communist Party, then got a job at a car factory in Nizhny Novgorod. On March 8, 1938, he was arrested by the NKVD and accused of Trotskyism. On February 5, 1940, the Soviet authorities handed him over to the Gestapo. He was accused of high treason and sent to Lublin prison, then transferred to a prison in Düsseldorf, where he died on January 25, 1942.

To the question, "What do the activities of the NKVD and the Gestapo have in common?" Wilhelm Mensing responds:

—That, as our great writer Theodor Fontane said 150 years ago, is "a vast field." What they have in common are the specific qualities of a secret police force. The Gestapo participated in the extermination of the Jewish population of the occupied countries—that is a unique feature. The number of victims of the NKVD is apparently greater. The numbers are different, but the mercilessness is the same. Both the Gestapo and the NKVD were tools in the hands of criminal rulers, of despotic tyrants.

We thank Konstantin Boguslavsky for his assistance in preparing this article.