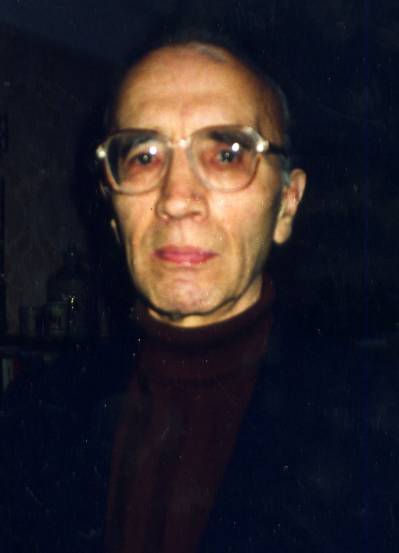

GURDZAN VV

I n t e r v i e w w i t h V. V. G u r d z a n

The audio recording was reviewed and the text was corrected on July 5, 2001.

V.O.: We are speaking with Vasyl Gurdzan in the hospitable home of Mrs. Yevheniya Kozak. What is the address here, Mrs. Yevheniya?

Y. Kozak: 12 Obolonskyi Prospekt, apartment 193, formerly Korniichuk Street. Thank God, it’s Obolonskyi now.

V.O.: This is taking place on November 8, 1998, on St. Demetrius Day. The recording is being made by Vasyl Ovsiyenko, and Vakhtang Kipiani is videotaping.

V.G.: I, Vasyl Gurdzan, was born in 1926 in the village of Liskovets, Mizhhirskyi Raion, Zakarpattia Oblast. This is one of the poorest raions in Zakarpattia, you could say, perhaps even the poorest. My parents were poor. My father spent twelve years as a migrant worker just to build a house—we didn’t have one, not my mother’s family, nor…

V.O.: Please state your date of birth, and your father’s name, mother’s, brothers’, and sisters’ names.

V.G.: January 23, 1926. There were two brothers and two sisters; I was in the middle. It so happened that when I was 14—I’m skipping ahead a bit—as you know, in 1939 we were occupied by Hungarian troops, and in 1940, I really didn’t like it. They were very harsh, even in the villages; there was always some military man, and he would come to the school… Well, I emigrated to Galicia at the age of 14. This was in 1940. And that’s where I ended up in a concentration camp. The Soviet troops had already arrived for the first time; it was the first occupation of Galicia. Then the war started in ’41, and they all fled because the German troops were advancing, so we had to make our way home.

I survived a concentration camp—it was a terrible concentration camp in Skole. Back then it was Drohobytska Oblast, but now it’s Lvivska Oblast, the city of Skole. It was a terrible camp. There were many people. After that, we were in prison for a short time—we were taken to a juvenile correctional facility.

V.O.: But why were you imprisoned in a concentration camp?

V.G.: Because I was fleeing from there, and they were suspicious of the older people.

V. Kipiani: How did you end up in the camp?

V.G.: Yes, I ended up in this concentration camp, like those who typically emigrated there, because the Soviets were already in power on the other side of the Carpathians, in Galicia. And they took those who emigrated there. They still treated us as minors, but they investigated the older people very thoroughly because the occupying authorities spread propaganda that we had sent spies there, and that’s why they investigated all the older people. Us too. But what could we do? During my first interrogation, they asked if someone had sent me, if someone had coached me, if there were any troops there. The border ran through my village. That’s what they asked. I couldn’t say anything like that, what I knew and what I didn’t. That’s how it was.

They didn’t keep us there for very long—about two weeks, I think, and then they sent us to a children's home. It was called “Novyi Rozdil.” I was there for about half a year, and I persuaded another boy to run away with me. We made it all the way to Lviv, where they caught us and sent us back. But they returned us not to prison, but to an FZO [Factory and Plant Apprenticeship School]. After the German troops passed through, we had to go home. But how? The FZO was close to a military supply depot, and if we were going to travel, we needed to get some provisions for the road. We pulled out a crate—we stole it. We thought we had gotten some canned goods, but it turned out to be cigarettes. We took a bunch of them to trade for food.

And so, as we were approaching the border, we ran into the security service, the Ukrainian police. They said: “We won’t let you pass like this because the area is mined. We’ll give you a man to guide you through.” And they handed us over to the gendarmes—the Hungarian field gendarmerie. They abused us thoroughly there—and then threw us into the Uzhhorod prison. We were in prison for two months. They really abused us there too. Well, they wanted to know—did our fathers, or neighbors, or some agitator force us to flee from Hungary, from Zakarpattia?

And they gave me a two-year suspended sentence, since I was a minor—I was already fifteen. But I had to report to the gendarme station, a twenty-kilometer walk from my village (there were no buses then), every other day.

And so a teacher in our village took an interest in me and started preparing me for exams. The school system back then was eight years of village school, after which you could enter a so-called "burgher school" for four years. She prepared me, I passed three exams as an external student, and I went to take the fourth. Her husband had a lot of influence in Uzhhorod, and I was admitted to the pedagogical lyceum. I was arrested in my third year at the pedagogical lyceum. They didn't arrest me where I lived in the dormitory. On an assignment, I had joined an organization called ZUP—Transcarpathian-Ukrainian Insurgents. I went on a mission to a safe house, and they arrested me there along with another person—two of us went; we were preparing an operation. We had to prepare some documents, some lists. We were getting ready for it; our commander—a very heroic and intelligent man—and it was only about ten years after my arrest that I learned they had eventually caught him. They caught him and shot him in Inta—they shot eleven men there; a major uprising was being planned. The group was larger, but those eleven were the organizers. And he was shot there.

V.O.: Do you remember the date of your arrest?

V.G.: My arrest? The fall of ‘46. It was sometime in October, late October.

V.O.: And what was your commander’s name?

V.G.: He wasn’t caught then. He was also in that apartment, but he had left just three hours before.

V.O.: What was his last name?

V.G.: He had a double-barreled name. He went by Harskyi there. No, he was Lysenko, but he went by Pysanko there. Yes, Lysenko-Pysanko—so he must have been Lysenko. And who did I learn this from? Maybe you know of him—Panteleimon Vasylevskyi. He lives in Drohobych, and he’s the one who told me this. We were talking, and he said: “Lysenko? Why, that’s the one who was shot for the uprising in Inta.”

Well, okay. I left off where I was arrested. I was in the youth wing of the Transcarpathian-Ukrainian Insurgents. The older members were the combatants. Generally, we were tried separately—them separately, us separately. They arrested more than thirty of them then; it was quite a large organization.

V.O.: Where was this case tried?

V.G.: In Uzhhorod, and the sentence was handed down by the oblast court. In Uzhhorod, and it was a military tribunal of the Carpathian Military District. Yes, the arrest was in October, on October 18. The investigation lasted for about half a year, and the trial was sometime in May of the following year. So what? The trial took place, and they put all of us in one cell after the trial. We were happy, singing songs, making up our own melodies, because we had one student who had a knack for it, a composer's bent. So we wrote songs.

V.O.: You didn’t say what sentence you received.

V.G.: They gave everyone ten years each and five years of deprivation of rights. But the deprivation of rights—that was only for me and two others, the two who were caught with me.

V.O.: Do you remember the articles of the code from that time?

V.G.: Of course! The same old Article 54, Paragraph 1-‘a,’ and Paragraph 11. It was a common article.

V.O.: Something anti-Soviet?

V.G.: Yes, agitation and propaganda, and paragraph ‘11’ was for group activity. If a person did something alone, it was without the eleventh, but if it was a military person, it was 1-‘b,’ while 1-‘a’ was for civilians.

Well, we traveled east in a Pullman car for almost a month. Strangely enough, in the first camp I ended up in, one of the leaders—there were three "thieves-in-law" there, and I don't know how they made their way through the railcar. And there were five of us students, from Galicia and Zakarpattia. They ordered the five of us to be moved out to make three spots for themselves. It turned out I was the sixth, so I stayed put. I felt sorry, but the boys left, and I was next to them. Two days passed. But these weren't just any thieves; they were "zakonnyky" [thieves-in-law]. They came and said, “Vasyl, you have a beautiful embroidered Ukrainian shirt—give it to us! We’ll get you an extra ration.” And they had some kind of connection with the guards. I had two of them. Then, after a while, again, "give us another." And they liked that I didn’t hold back, that I gave them away. They said I wouldn’t need them in the camp. And so I get to this first concentration camp.

V.O.: And where was this?

V.G.: The first one was in Dzhezkazgan.

V. Kipiani: Steplag?

V.G.: Peschlag. And then he suddenly saw me and asked where I was. I said I was in such-and-such a brigade. There was a copper mine there. The work was such that if a healthy guy, first category, worked there for a month, he’d be disabled. That copper dust, you can't spit it out—the copper settles, and there was no ventilation, no irrigation. They crippled people terribly there. And when I saw this, I decided not to go. Once, a second time, and they drove me to the point where I could no longer walk… Well, but that was later. And then they transferred me to another camp, and I met that guy there, and he asked where I was. I told him which brigade and who my brigadier was. A short time later, the head of the KVCh (Cultural-Educational Department) calls me in and asks what I can do. I knew how to draw a little. “Ah! You’ll be in the KVCh.” But I wasn’t there for long.

I went through almost twenty camps. They never kept me in one place for long…

V.O.: What regions did you end up in?

V.G.: Dzhezkazgan, then Spassk (I was there twice—the first time and the second), then the twelfth concentration camp, Karabas—a terrible place, logging camps. Then I was in stone quarries. That was very hard labor. I was in a coal mine right after Dzhezkazgan. The second time I ended up in Spassk—that was absolutely terrible, the last stage of dystrophy. It was the last stage, and I couldn't eat or anything—it all just flowed through me.

And an interesting thing happened there. I recovered a little—well, there was a quarantine, and from Zakarpattia, maybe you've heard of Ivan Korshynskyi, who was recently a People's Deputy—he saved me. I was wasting away. This Korshynskyi, somehow we came together—me, him, some other guy from Zakarpattia, some boys from Galicia. And he said, "Eh, Vasyl!"—and he hugged me like this, "Come on, lift up your shirt!" And I had a belly full of fluid. He had been arrested in his second or third year of studies; he was a medic himself. And he was very capable at it and interested, and in that same Spassk, the Deputy Minister of Health of the USSR, Kolesnikov, took a liking to him. He was in charge of the hospitals—there were two hospitals there: one in the zone and one for the workers. So, he really liked him because he was a good-looking boy and very curious. And he took him under his wing. He was present at surgeries, autopsies, and back then Kolesnikov saved a lot of people. Transplants were being introduced then, and there were these terrible stomach diseases. And stomach operations are very difficult. And transplants. He knew how to do it; he knew how to do a lot. He was allowed not to have his head shaved; he walked around in his own civilian clothes, not camp attire. That's how much they respected him. Colonels would come to him for consultations.

So, this Korshynskyi immediately grabbed me, told me to come see him, and he got me a place in the hospital there. It wasn't that I didn't want it, but it wasn't easy to get into the hospital... There were two Hungarian doctors there. And he was with one of them near Kolesnikov. And they called me in, showed me how to fake my symptoms... There was a commission, so they showed me how to fake it, how to lift my leg, when to say it hurts, when it doesn't, so they would diagnose me with sciatica—and that's a terrible disease, they hospitalize you immediately for that. So I spent about two months in that hospital, and I recovered. And the other doctor would hide my file so I could stay there longer. I would draw all sorts of medical illustrations for him. And when I was released…

V. Kipiani: In what year—‘56?

V.G.: Yes, I served nine years. Because after Beria was shot, special commissions (they were called “Moscow commissions”) went through the camps, reviewed these files—who, what for, how—and they reduced sentences.

V.O.: So they reduced yours?

V.G.: Yes, I was in the same camp with someone from my case, and they released him, but not me. And we were from the same case, and I thought they would release me too. I was tormented, couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat—he was released, but I wasn’t! They say they wanted to give me a sentence where I couldn't go to Western Ukraine, but would have to stay there. Someone else said it was because they had requested my documents, which weren’t at the administration office. So I don’t know for sure, but I was tormented for almost a week, wondering what was going on and why they weren’t releasing me—we were from the same case. Yes, that was in 1955, from 1946 to 1955. I was released on April 5, 1955.

So, after my release in 1955, I was home on the second day of Easter. Well, I had to work somehow. People from our village were going to work in the logging camps. I signed up for that brigade and went. But I had no luck because the forest they offered was one where the previous brigade had already cut down all the good, larger trees. And people didn't agree—it wasn't profitable. So we went home. Then, my two sisters were going to school, and they found out there that I knew how to draw a little, and the school director asked me to design a wall newspaper. I did it, and that wall newspaper won first prize at an exhibition in the raion.

About a week passed, and the village council summons me and says that the raion committee said I should go there, to the third secretary. I said I wouldn’t come because there was no way to get there. So they told me that a collective farm truck would be going tomorrow, and I could get a ride.

I went. This third secretary, a Russian, Zubkov or Zubov, says: “We know everything, that you went to the logging camp, and we know you can draw—do you want to work at the House of Culture?” I say: “Why not?” “Then let’s go.” We went to the director of the raion House of Culture, and I stayed there. I worked there for about a year or more.

And suddenly, the newspaper *Mizhhirska Zirka* [Mizhhirya Star] published a libelous article about me, saying that the Soviet government gave me everything, but I—I had painted a holy icon for someone or something like that—and he, they said, paints holy icons. That made me angry, very angry. And what did I do? I asked the accountant at the House of Culture for a typewriter. He agreed, we went to his place after work, and I took it and typed up about thirty protest letters. They summoned me and even gave me some literature to read, and a book by our writer, Smolych has a book like that. It was about nationalism and all that, and I said directly that it had no effect on me whatsoever, because I know what it means to be a man and not to change your life for some cheap political manipulations. So I took those letters and distributed them to every school, every village in the raion, and to the village council. Oh, God! They started trying to catch them all, so people wouldn't read them, but the letters had already spread.

The prosecutor summons me. He says: “I know, I know, why did you do such a thing?” “And why did they write that I have no right to draw, and write such slander about me?” He says: “You know what—I’m going to show you a document I received. The document says that those released from camps should be the first to be found work they can do. Don't worry—what they wrote about you in that libelous article is nothing.”

After that, the one who hired me transferred to another job—from Mizhhirya to Khust, where he headed the House of Culture. And he urged me to go there. I went there. And after that, I met—there was a group that came from Kyiv—those who were planning forest plantations, because the mines needed supports, and a terrible amount of forest was being cut from the Carpathians. And that commission was planning new plantings. And in that group, I met people who urged me to go to Kyiv, that there was a higher art school there, and a lower one—the ones that give an artistic education. They still exist today. They teach the culture of drawing...

V.O.: Some kind of college or what?

V.G.: No, no, it's an art school, attached to Houses of Culture, it’s somewhere around here near the planetarium.

V.O.: So you started studying there?

V.G.: Yes, but not for long.

V.O.: In what year did you go there?

V.G.: That was around 1962-63. Before that, I was in Kaniv.

V.O.: And that incident with the newspaper publication—when was that?

V.G.: That publication? That was around when I was released—around 1957.

V.O.: And in 1963 you ended up in Kyiv—is that right?

V.G.: Yes. In 1961 I ended up in Kaniv—and how? When I arrived, there were some acquaintances here, and they recommended me and spoke to him. It was the great-grandson of Kateryna, Filya Krasytskyi—the one who was the deputy director of the Shevchenko Museum, the great-grandson on Kateryna's side. They recommended me to him. I went to him, and he said he would give me two addresses in Kaniv where I could get a job. That's how I ended up in Kaniv. There, indeed, they found me a job based on his address and his recommendation. I spent two years there, and then they… This was the 1960s, and whenever there was an event, they would let me know, and I would come, flying on the “Raketa”—I think they still exist. By the way, I was at that evening dedicated to the playwright Mykola Kulish, and Les Taniuk, the current head of the Memorial Society, was speaking, and Uzhviy was wringing her hands and twisting her fingers in opposition to his speech, because he was young, spoke well, and since they didn't want to stage his plays, he was later forced to go to Moscow, as they wouldn’t give him work here.

So there were a lot of people at that event, and then, I somehow settled in here, and they set me up—Alla Horska. I would sleep over in her workshop—on Chorna Hora [Black Mountain]. And Semykina's workshop was nearby. Then I spent several nights at the artist’s… his painting is “Trembitari”... Well, there…

V.O.: You were in the circle of the Sixtiers, you attended these evenings…

V.G.: Halyna Zubchenko was there, she knows well the ones I mentioned, Semykina knows me well, Kutkin the artist.

V.O.: The arrests of 1965 didn’t affect you?

V.G.: I had several searches. I still have a few of those… somewhere.

V.O.: Did you have any samvydav?

V.G.: They took it!

V.O.: And what did you have?

V.G.: I had several copies of Dziuba's “Internationalism or Russification?”

V.O.: In what form—typescript or photocopies?

V.G.: Typescript, on very, very thin paper.

V.O.: So at that time you got away with just summonses?

V.G.: I got away with it because when they asked where I got it, I said I was sitting in a movie theater and some guy sitting next to me offered me something to read, but I didn't know him, had never seen him before, and I don't know where he got it. “And do you know what kind of article that is?” I say I don't know anything about any articles—I have the right to have what I want, and if I were distributing it, that would be another matter. But the fact that I had it—you're taking it, you took it, and that's that. I say, there's no law against... And what did I do? I wasn’t distributing it, was I? I just had it. No, if you were distributing it, then there’s an article, but for just keeping it, there’s no article, and if you’re going to say who gave it to you—well, then he’s the one in trouble.

V.O.: And what about “possession with intent to distribute”?

V.G.: Well, you know, prove my intent.

V.O.: They didn't have to prove it back then.

V.G.: Well, nothing happened to me for it, but they confiscated a lot. I had a lot of Khvylovyi, and Hrushevsky.

V.O.: Do you remember in what years those searches were?

V.G.: That was in the seventies, around 1972-73-74, like that. There were constant searches. And by then I was working as an artist at the Vatutin cinema—it's gone now, they sold the building. The Vatutin cinema was on Chervonoarmiyska Street. And the last time, when I went to work as an artist at the Chelyuskintsiv cinema, I was working at the "Zhovten," in Podil.

V.Kipiani: In the eighties, can you name any samvydav or any people you maintained contact with? After the arrests of 1972.

V.G.: I even wrote something like that myself. I can talk about it now. Do you know Yevhen Obertas? He did a lot [unintelligible], then gave it to me. There was something {of mine that I was distributing}, I did it through him.

V.O.: Did you know any members of the Helsinki Group? Was Oksana Yakivna Meshko perhaps known to you then?

V.G.: No, not then, but I got to know her very well later. I even tried writing something like that myself and gave it to her. I used to go to her home, she needed something there. Who else? I communicated with these artists—I might not remember them all right now. We used to meet at Yevhen Obertas's place, he had many acquaintances there.

V.O.: And when the members of the Helsinki Group were being arrested—did that not affect you? In 1977 and onward.

V.G.: Seventy-seven? No, they just sent some people to have talks with me—you know, that was a common practice. But other than that, no. But when events like that happened, they always summoned me to the militsiya and forced me to sit there until three, until four, we'd sit there from ten o’clock—for nothing, just to sit.

V.O.: And what events?

V.G.: For example, by the Shevchenko monument on May 22, or other similar events, they watched to make sure people didn’t gather in groups or anything like that. It was a practice at the militsiya in the Moskovskyi district—they always summoned me: “Wait, sit for a bit, the chief isn’t here,” or something like that, and I would sit there for five or six hours.

V.Kipiani: I know Obertas was summoned in Berdnyk's case, and they confiscated documents from him—were you not affected by that at all?

V.G.: No, no.

V.Kipiani: And in the eighties, did you retire?

V.G.: In the eighties, in ‘89, our All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners was organized, and I was immediately elected deputy head.

V.O.: But before that you were in the Ukrainian Culturological Club? By the way, today is St. Demetrius Day, and people are gathering at Dmytro Fedoriv's place, at 10 Olehivska Street. Are you going?

V.G.: When?

V.O.: They're already gathering around this time. At Dmytro Fedoriv’s, 10 Olehivska Street.

V.G.: I know.

V.O.: How did you find out about that culturological club? That’s interesting.

V.G.: The first person who signed me up was Oles Shevchenko. He was the first person to put me on the list. And it wasn’t in a building; we just used to gather like that.

V.O.: In Frunze Park or somewhere else?

V.G.: The first meeting wasn’t in Frunze Park—the first was in Obolon, there’s a café there—I don’t remember what it was called—where Mr. Sverstiuk first spoke and talked about Dovzhenko. That was the second one, not the first; I wasn't at the first. And then we started meeting in other places, and then regularly at Fedoriv's.

V.Kipiani: And how did you meet Shevchenko?

V.G.: It was simple, when they asked who wanted to join the Ukrainian Culturological Club, I went up with someone else, and he wrote my name down. And from that time on, I regularly attended those meetings.

V.O.: And then you were in the Ukrainian Helsinki Union?

V.G.: Yes, I basically moved there automatically from the Culturological Club.

V.O.: Well, the entire UCC joined the UHU. And what about the founding meeting of the Society of the Repressed on June 3, 1989?

V.G.: Yes, what happened was that an arrangement had been made with the House of Artists, they had agreed to give us a space. Well, that was it—we gathered, at nine or ten o'clock, I don't remember exactly, and they refused us. They refused, and so we went across the street, where that rotunda is, and we held it there in the open air… Still, they came to chase us away. Everything was quiet, there were no scandals. That was the first founding meeting.

V.O.: And you were elected there...

V.G.: Yes, elected deputy head, and the head was Yevhen Proniuk.

V.O.: Tell us a little about the Society’s activities—you work there professionally, don’t you?

V.G.: Yes, I worked in it for nine years, until this year, as deputy head.

V.O.: And a member of the editorial board of the journal "Zona"?

V.G.: That came later… although not much later, that same year. For the upcoming year, 1999, “Zona” will come out with a new cover, and I'm working on that right now. The tenth anniversary, 1989-99. But it will be a small issue, though the name will be the same. But it will still count as an issue of “Zona” for the tenth anniversary. I worked on it. Well, you know, you can see how primitive the first cover was—primitive, but it was the best I could do.

V.O.: That's your cover, right?

V.G.: Yes, yes. It became more complex over time. And there were some articles in it.

V.O.: Do you have publications?

V.G.: Yes, in this one too… About seven or ei... V.O.: We need to compile your bibliography.

[ E n d o f t r a c k]

V.G.: …There are people who are very interested now. These were, one might say, very close, although they were in different parties. This was Konovalets and a man named Marchak, Mykhailo Marchak. I knew Mykhailo Marchak, but he was an older man then. And how did I know him? Well, we just talked; he was a very nice, pleasant man.

V.O.: And which organizations were these people from?

V.G.: Well, you know Konovalets, and he was, it seems to me, from the beginnings of Bahrianyi’s—the RSDP. They were just… but Marchak was a very good person, intelligent and calm, and Konovalets was the same. They had a great deal of sympathy for each other, even though they were in different parties.

V.O.: And what party was Konovalets from?

V.G.: He was from the UVO}, but it was later restructured…

V.O.: So you’re talking about Yevhen Konovalets? You knew him?

V.G.: Yevhen, Yevhen. I didn’t know Konovalets, but I knew Marchak, who was close with him. Now, there's another person from the sixteen members of the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council; only one is left. Some were shot, some emigrated, but this was Stepaniak, Mykhailo Dmytrovych. He himself is from Bohorodchany, near Ivano-Frankivsk, from Bohorodchany. I can tell you some very interesting facts about him.

V.O.: Please do.

V.G.: I was very close to him, although he was older than me. But somehow it so happened that I ended up in the same camp where he was. So, he was released. But he was released later. I have his letters. I gave a letter he wrote to me to Kuk. He never returned it—well, let it be. Vasyl Kuk knew him well.

So, he was released. He got married in a neighboring village. She's a doctor. I'm talking about Stepaniak. And so he fell ill but didn't want to go to the hospital—he knew it was dangerous. He had some kind of stomach illness. And in Ivano-Frankivsk, there was a man who knew him from the camp, but he was a dubious character. And he talked him into it: "Go to the hospital, and I'll look after you." He was a doctor from Ivano-Frankivsk himself. So Stepaniak went to the hospital, and he came out paralyzed on one side, unable to speak. He lay like that for a while. I went there and talked with his sister, I was at his grave. And that's how it was, it's certain that this man... He really didn't want to go, but this guy guaranteed his safety. And he came back from there—he suffered greatly, he was already paralyzed. One side was paralyzed, then the other—and that was it.

Now, I was also acquainted with a very interesting person—with Marchak. This man, you could say, never finished any school, a peasant. You see, when Zakarpattia was part of Czechoslovakia, Marchak was elected all the way to the Soim [Diet].

V.O.: And how did you meet him?

V.G.: His son was also a people’s deputy, Klympush. He was a minister for a short time. His father’s name was Vasyl. And he told me the whole story of 1917. My God, you know, history is such an interesting thing! Hutsuls ride on horseback and proclaim a republic—the Hutsul Republic. The Czech writer Olbracht described this event. He wrote a whole novel about it. And so, this Vasyl Klympush could speak so beautifully, constructing his phrases with such culture—simple, but so intricate, nothing superfluous. And it was very interesting to be with such a person…

V.Kipiani: What was he convicted for?

V.G.: Because they, the Klympushes, all of them—his son, Dmytro Klympush, was the head of the Carpathian Sich when there was a Carpathian Ukraine. He was the head of the Carpathian Sich, but his father didn't sit on his hands either—he was also a very active person. And even just for that son—the other sons were less involved, but Dmytro was very zealous, he was the head of the Carpathian Sich. What is there to say? They were, I believe, engineers, his sons, but I can't say for sure. It seems so, because if he was the Minister of Transportation...

And there was another person—I saw him, people pointed their fingers at him and said: “Lenin’s secretary.” Lenin’s own, an old man, with a beard…

V.O.: And his last name?

V.G.: I don’t know.

V.O.: And what about Ukrainian figures?

V.G.: Well, Stepaniak was one of them. Now, a very interesting person—Yaroslav Dashkevych. We were in the camps together. I was being released when he was in Spassk, and it was my last time there, we said our goodbyes. He was still left behind. A very good man, and there were some other matters there, that…

V.Kipiani: Was there any self-help, any kind of organization in the camp?

V.G.: We were always organized.

V.Kipiani: Or was there any ongoing work?

V.G.: Well, what kind of help, from where? There was absolutely none. If a parcel came from relatives at home—that’s a different story, but help of any other kind... In the 1960s, there was some help from abroad or from charitable organizations. But back then, no one even knew we existed. To be honest, parliaments knew about the Sixtiers, presidents abroad knew, but about us—it was all quiet, nobody knew anything. And even correspondence was limited—twice a year, and that was it.

V.O.: Can you recount any episodes about the uprisings in the early 1950s?

V.G.: Yes. I remember when I arrived at one camp, the *vory* [thieves] were robbing it. They were called *suki* [bitches], because there are *vory*, and there are *suki*. They are different, because the former have their laws. A *vor* has some kind of code; he won’t rob a poor man, but will say: “Listen, give it here. Don’t be stingy.” He’ll ask you to give it. But the other kind will just grab it, rip it off—those are the *suki*, they have no code. But the *vor* has some kind of ambition—he robs banks. And so I arrived, and they were running wild—robbing the mess hall, not working, abusing people... Each one takes a small sack, cuts two holes for the eyes in it, puts it on, turns his padded jacket inside out so the numbers aren't visible, and at a certain moment, when it's late, dark, when the lights are out and it’s time to sleep, they deliberately turn off the lights (the guys there were electricians, they knew how to do it). And in groups of three or five—the threes were the stronger ones—they go in, they already know who is lying on which bunk, and they gave them a good beating there. They didn't kill anyone, but they beat them well. The victims screamed, ran to the guardhouse, and soon the military surrounded the place.

The next day, even though they had seen that I hadn’t gone anywhere, I was sitting on my bunk and wasn’t involved—they still took us, eight men, called us to the guardhouse and took us to that same Spassk. And in Spassk, there were three more camps, surrounded by internal walls, an internal prison. We declared a hunger strike there for six days. For three days we were without anything, and on the third day, we took water. We took water, but we didn’t eat for six days—demanding the oblast prosecutor. And the prosecutor did come. They tried to persuade us, to intimidate us, but on the sixth day, he finally came. Then, after the hunger strike, they gradually gave us food so we wouldn't get a twisted bowel. That's one moment I could tell you about.

V.Kipiani: Say this now, because my tape is running out: "I am Vasyl Gurdzan, today is November 8, in the presence of Vasyl Ovsiyenko…" Okay? Just so we can note at the end when it was, who it was.

V.G.: I am Vasyl Gurdzan. Today is November 8, in the presence of Mr. Vasyl Ovsiyenko, and also Vakhtang Kipiani, the year is 1989.

V.O.: Why 1989? It's 1998!

V.G.: Yes, the other way around.

V.Kipiani: Okay, thank you.

V.O.: I wanted to ask you a few more things. You mentioned your father. What was your father's name? Vasyl, right?

V.G.: My father? That's an interesting question. You know, it was a very, very poor family. And when my father was little, he used to tell people that the family was so poor that his mother and father hired him out to another village to herd cows. He was very small, and they always reproached my grandfather: “Why did you give him away? You sold your son!” And so he was registered, and he went by that name, because back then the birth records were with the priest somewhere in another village—they wrote down Vasyl Prodanovych, and that’s what his documents said: Gurdzan Vasyl Prodanovych.

V.O.: What years did your father live?

V.G.: He was born in 1886 and died the year before my release—that would be in 1954.

V.O.: And your mother—what was her name and maiden name?

V.G.: Her maiden name was the same—we had a lot of Gurdzans. Even now they confuse me with the head of the KUN [Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists] in Zakarpattia Oblast—he’s also Vasyl Gurdzan.

V.O.: And what was your mother’s name?

V.G.: Mariya Mykhailivna.

V.O.: And what years did she live?

V.G.: She was five years younger than my father, born in 1893, and she died when she was 80[?], she outlived my father. She died in 1983.

V.Kipiani: Do you have brothers and sisters?

V.O.: You said you had two brothers and two sisters. Name them in order.

V.G.: The first was Ivan—he died two years ago. Another brother—Fedir, the second one. He’s in Prague now. He was in the military. His story is complicated. He was in prison in Budapest. And when the army was advancing, they were bombing Budapest, and he was buried under the rubble. And they dug him out. When they dug him out, they wanted to draft him into the army, but he didn’t want to go. He joined the Czech Legion, which was commanded, as you know, by General Svoboda, who organized it here. And almost all of them were from Zakarpattia, because Zakarpattia Oblast was under Czechoslovakia until 1939. And in Siberia there were very many of those who had been in prisons, who were exiled—so there were a lot of people from Zakarpattia. And General Svoboda said that they were his subjects, of Czechoslovakia. And he organized them, and Fedir joined this Svoboda's army. He rose to the rank of captain. And when he reached that rank, there were many like him, so they were given options: either stay in the army and get the next rank or whatever, or return home and we’ll pay you some money, or go to the Sudeten farms, from where the Germans had been expelled—go and take a whole farm for yourself, there’s a house, and cows, and horses. But not many wanted to go there, because the Germans were killing people there at night. So my brother chose to stay in the army. And so he served there in that army. He got married there, and has a family there. He was born in 1924. And my brother Ivan was from 1912.

Now the sisters. They have already passed away.

V.O.: Younger?

V.G.: Younger.

V.O.: What were their names?

V.G.: Mariya and Kalyna. Not Kylyna, but Kalyna.

V.O.: And the years of their lives?

V.G.: Their years? Well—farm work, at home. They weren’t rich, you know… There was always a cow and a calf. School too—village school, five or six grades and that's it. Mariya was from 1930, and Kalyna from 1933.

V.O.: And when did they die?

V.G.: Mariya died ten years ago, and Kalyna died last year.

V.O.: And one more detail I want to ask, because one must know this about a person. You were swept up at fourteen years old—and you went out into the world. But how did your family life turn out? Do you have a wife? Do you have any children, descendants?

V.G.: When I had my last search, I was working as an artist at the Vatutin cinema. And when they conducted this search, they told me to be gone within a week.

V.O.: What year was that?

V.G.: Eighty-one. And so they told me that was it. But how? The district police officer came and said, "Come see me tomorrow with your passport." I went, brought my passport. He looked and looked at something, and then he says I need to change my passport, that he will call the passport office, and I should go and get it tomorrow. I handed over my passport, he wrote me a slip.

V.O.: They evicted you from your registered address?

V.G.: They evicted me and told me to be gone within a week, to avoid a scandal. And at that time, I already knew Yevhen Obertas. I went to them and told them what happened. He was thinking about what to do, and suddenly I... When I was working as an artist at the Vatutin cinema, a woman worked there as a cashier. And somehow I ran into her and said that I would be leaving soon, that I was getting ready. “Why? Let's get married.” Before doing that, I went to Yevhen and said, here's the situation. And he says: "Don't be a fool! This way you'll show them that you're staying. Do it, and if things go bad or she’s not right—you'll get a divorce. But you'll have your registration." We talked about this two or three times—I really didn't want to. Well, okay, I thought. And so I got married.

V.O.: Please state her name and address, so it’s recorded.

V.G.: Her name is Yelyzaveta Danylivna, her last name from her husband (she was married before) is Kosyakova. Address: Kyiv-212, 2 Bohatyrska Street, apartment 349.

V.O.: And you even have a phone number?

V.G.: The phone number is: 413-88-29.

V.O.: Let this all be documented. I thank you. Perhaps some other questions will arise. [Dictaphone turns off].

V.G.: ...I had given him a few copies. And then, when I read it, I was so surprised. Either I've matured a bit—it was naively done, the language, and the mistakes in it… Now, maybe, I write a little differently.

V.O.: Have you considered writing some memoirs about yourself or publishing them?

V.G.: I’ve never written anything about myself.

V.O.: Never written. I saw a few of your articles.

V.G.: I’ve never written about myself. I feel that it’s… And even now, this—that I’m alongside such…

V.O.: You see, the history of a people is made up of the life stories of specific individuals. And you are in that history, and the more that is recorded on paper, the more reliably that history will be true, not some corrected version. We will definitely transcribe this, give it to you, and you will correct it, add to it, and it will be preserved. Let it be.

V.G.: I’m not used to situations like this. I was very anxious these past few days—that’s why I was putting it off, why I didn’t want to.

V.O.: I know that you are not a well man now—what can be done. [Dictaphone turns off].

V.Kipiani: And they beat you?

V.G.: That was last year, it was already September. I was at someone's house. I couldn't and didn't want to say who afterwards. I was at someone’s house, and was leaving from there. I was walking from the Minska metro station. I waited and waited—no bus, so I started walking. I immediately sensed that someone was there. I turned around once—yes, five men are walking. Well, let them walk, I’ll keep going my way. And somewhere in the middle of the road they catch up to me: “Got a smoke?” I say, yes, and I pull out my “Pryma.” “We don’t smoke that kind.” And they said something to me about my language, I don’t remember what now. I said something a little sharp back. And then the one behind me hit me, just like that! And the one in front hit me here, and after that I don’t remember—another blow to the head… This was around eleven o’clock. I looked up—I was no longer on the road; it had been on the asphalt, on the road. Now I was on some grass, I look—they had dragged me off. I lay there for about four hours, unconscious. How do I know how long I lay there? Because when I finally dragged myself home, I couldn't get my bearings at all. It was very close to home, but I just couldn't figure out where I was.

Well, of course, my glasses flew off, they were gone. This ID card I have was thrown aside. And I came home bloody, my head had a very large wound here. It was busted open, everything hurt, bruises here. I came home, and my wife immediately got the neighbor… I said I don’t want any militsiya, no ambulance. I didn’t want anything. But the neighbor went and called for an ambulance. The ambulance arrived—to clean, to apply compresses. And then the militsiya. The ambulance itself had called the militsiya. Well, a report and all that... I said, I don't need anything, I don't want to deal with you. I knew that no one would ever find them or even try. Then they called me in again, and then again.

But I didn't say the most important part. The last words I heard, because one of them stood to the side and said to them: “Vot tebe za samostiynist!” [“This is what you get for independence!”]. I heard those words, and after that I didn’t hear anything. That's how it was.

V.O.: And it wasn't investigated—there was a statement from the Society of the Repressed, but it all just vanished...

V.G.: Yes. Chornukha wrote an article, it was in the newspaper.

V.O.: We also published something in “Narodna Hazeta” at the time. Well, they don't look for people like that. If it were something anti-Russian, they would have found them.

Well, alright. We thank you for these stories. We have been recording Vasyl Vasyliovych Gurdzan, on November 8, 1998, in the home of Mrs. Yevheniya Kozak.

[ E n d o f r e c o r d i n g]

Vasyl Gurdzan died on June 19, 2001. A farewell ceremony was held at the premises of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and the Repressed on June 23. On the same day, a cremation took place at the Baikove Cemetery. The deceased did not review this text, but I, Vasyl Ovsiyenko, reviewed the audio recording and corrected the text on July 5, 2001. On the same day, I did a literary edit to publish it by the fortieth day after his passing.

Published in the journal “Zona” under the title: In Loving Memory of Vasyl Gurdzan (23.01.1926 – 19.06.2001) / Zona, No. 16. – 2002. – pp. 343–353.