B.Ye. Zakharov: Tell us, what kind of family were you born into, what values did this family have, about your childhood and your memories. Please.

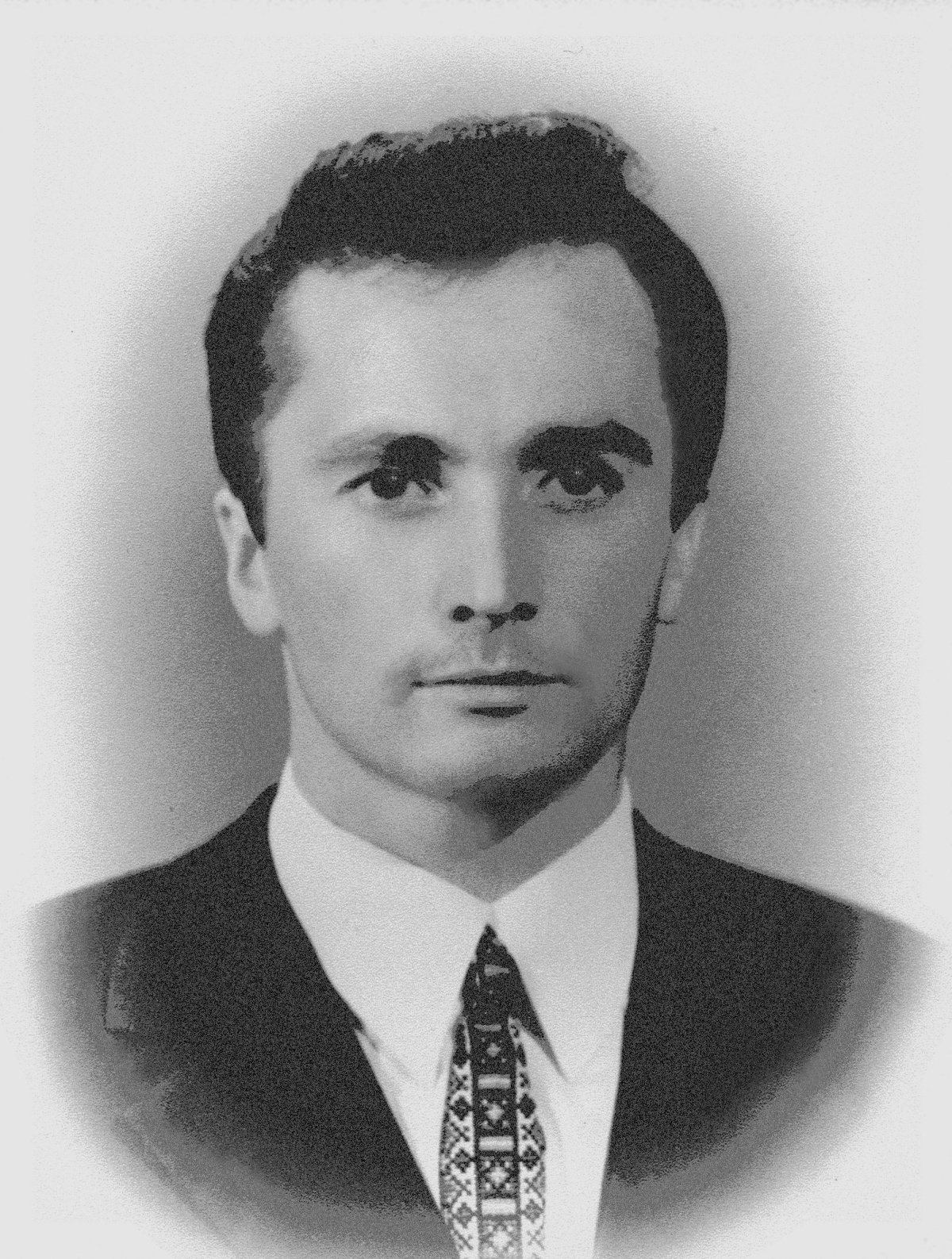

V.V. Ovsiyenko: I am Vasyl Ovsiyenko, my father’s name was also Vasyl, and my mother was Frosyna Fedorivna. They were simple peasants from the village of Stavky. Since 1924, that village has been called Lenino, and they just cant manage to change the name. They were born there, and they lived there. My father, who was born in 1904, died in 1976, and my mother, thank God, is still alive. So Frosyna Fedorivna, née Pidsukha, born in 1910, still lives in that same village of Stavky.

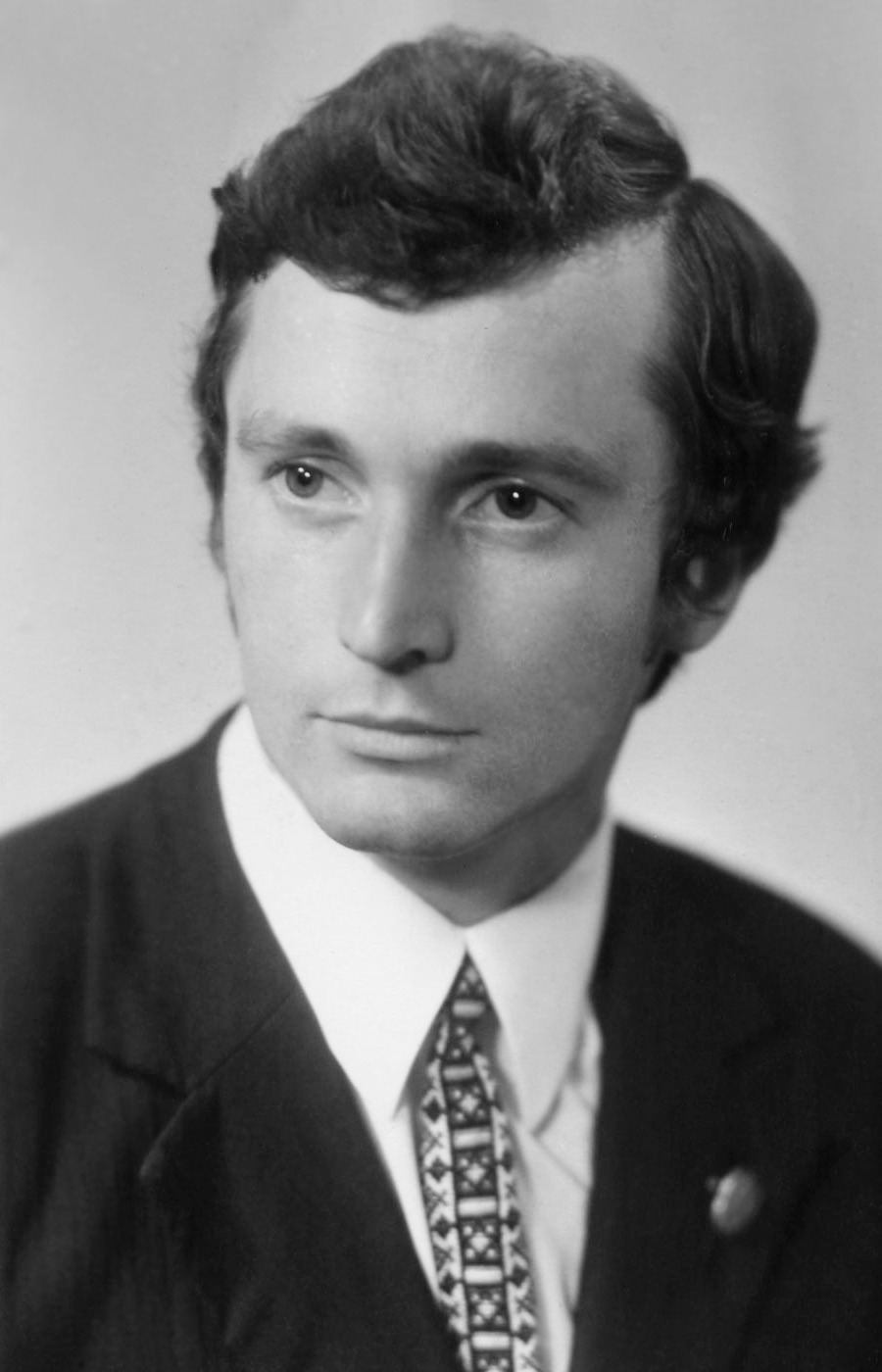

Our family was large. My parents had ten children, and I was the ninth; I was the youngest in the family. There are six of us still alive today. I attended secondary school in that same village of Stavky from 1956 to 1966. I did well in school, was sometimes a straight-A student, and graduated with a silver medal. From a young age, I was passionate about drawing, and then, from about age 13 or 14, I became interested in the written word. I tried to write poetry. I had an inclination for literary creation, and perhaps it was this realization that the Ukrainian word was in an abnormal state in Ukraine that pushed me toward the idea that something was very wrong with this society.

No one in school had any particular influence on me, because it was a village, and that was that. The teachers weren’t particularly significant individuals who could guide me, but starting around the ninth grade, I actively contributed to the district newspaper, where Vasyl Tymofiyovych Skurativskyi worked. Today, Skurativskyi is well known as an ethnographer, having published several very fine books on the subject. By the way, they have already been nominated for the Shevchenko Prize, and it’s a pity that Vasyl Skurativskyi has not yet been awarded this prize.

So, at that time he was working at the district newspaper *Zorya Polissia* (Star of Polissia) in Radomyshl, in the Zhytomyr region. I met him at a literary studio, and he told me a little about the dissident movement, which wasn’t called that at the time. In particular, I think it was from him that I first heard that Ivan Dziuba had written the book *Internationalism or Russification?* and that this book was very popular. I don’t know if he had read the book himself or not. So, I graduated from school in 1966 and tried to get into Kyiv University to study Ukrainian philology, but my attempt was unsuccessful. I worked on a kolkhoz for six months, doing various jobs. Then, at the end of 1966, I was invited to work at the editorial office of the newspaper *Zhovtnevi Zori* (October Stars) in the town of Narodychi, which is now in the infamous Chornobyl Zone. A new district was being opened there, and with it, a newspaper. The deputy editor of the district newspaper in Radomyshl, Dmytro Baranchuk, was appointed editor there. He knew me and took me with him. I walked all over that Narodychi district on foot, because the editorial office didn’t have a car, and I saw how people lived there.

B.Ye. Zakharov: What were your views then, and what was your attitude toward the authorities and what was happening around you?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Of course, I was a member of the Komsomol, and perhaps even a sincere one, from the age of 14. But when I saw how people lived, especially in that Polissia region, when I went into those houses, something crept into my mind, you know, some serious doubts that something was very wrong in this society. Especially when I managed to get into Kyiv University in 1967 to study Ukrainian philology, I met young people there, and some professors. And besides, Kyiv is a much larger sphere, and these conversations among students, and then visiting Ivan Honchar’s ethnographic museum, which is still there on Pechersk Hill, and then, I think, the first thing that fell into my hands was the diary of Vasyl Symonenko with his poems. This was the typescript that Ivan Svitlychnyi had put into circulation. It was a collection of poems and his diary.

Then someone gave me a typescript photocopy of Mykhailo Braichevskyi’s book *Reunification or Annexation?* It wasn’t a book, but a long article. After that, I got my hands on a photographic print of a foreign edition of *History of the Rus’,* by an unknown author from the late 18th century. That work also opened my eyes to a great extent. And the student atmosphere itself, attending various evening events—all of this prompted reflection. And in the spring of 1968, my English teacher, Feodosiy Markovych Sliusarenko, dared to give me a photocopy of Ivan Dziuba’s work *Internationalism or Russification?* He also gave me the film negative. He gave me two prints; I read these prints myself and gave them to my friends to read—of course, conducting such work with caution, as it was known that anyone who distributed samvydav wouldnt last long at the university. For example, I didnt go near the Shevchenko monument on May 22, because I knew that all the students who went there were candidates for expulsion. Since I had this opportunity to get samvydav, I decided right away that I should do it, but without attracting too much attention, to last as long as possible.

In the summer of 1968, using my old camera equipment, I made, I believe, six prints of Ivan Dziubas work. I had two film rolls. One was 126 pages long, and the other was 181. I dont remember now how many prints I made of each, but as you can understand, it was a considerable amount of work. I gave these prints to my acquaintances, and they were circulated. By the way, not a single one has survived from that time. So, by 1968, I was fully committed; I completely shared the views of Ivan Dziuba and that circle of the “sixtiers.”

It can certainly be said that this was a critical attitude toward the existing reality, but Ivan Dziuba’s work is structured as neocommunist. He criticizes the so-called Leninist nationality policy by using the very same doctrine. And it is quite rightly defined as a neocommunist work. Although I was absolutely sure that the circle of people around Dziuba, or more precisely, Ivan Svitlychnyis circle, held somewhat different, more critical views of the existing system. But, evidently, this tactic was chosen specifically.

Sometime in 1968-1969, I was a sophomore at the university, and I met Vasyl Lisovyi there. He was a graduate student in philosophy at the university at the time. I believe it was his first year lecturing at the university. Before that, he had worked for a short time in Ternopil, teaching at the medical institute. I spoke with him on several occasions. He took notice of me and began giving me samvydav quite regularly. As I later found out, he was close with Yevhen Proniuk. Yevhen Proniuk is now a Peoples Deputy and head of the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons. He was acquainted with Ivan Svitlychnyi, and again with Vasyl Stus, Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk, basically with that entire circle, with Yuriy Badzio. But he probably chose the right tactic in not introducing me to those people closely, because it would have risked expulsion.

This source of samvydav was constant. For instance, in 1969, virtually all issues of the *Ukrainian Herald* passed through my hands, starting from the first—one, two, three, four, and there was a fifth. As for the sixth, thats a separate story, what happened with issue number six. I didnt know then who published this journal; it only became known much later that it was edited by Viacheslav Chornovil. For example, Mykhailo Osadchy’s book *Cataract,* about his arrest and imprisonment—that was an extraordinary thing. Yevhen Sverstiuk’s article about Oles Honchar’s novel *The Cathedral,* called “Cathedral in Scaffolding,” was a profound analytical piece. Or smaller articles by Yevhen Sverstiuk, like “On Mother’s Day.” There was also a rather large typewritten article, I remember, called “Ivan Kotliarevsky is Laughing.”

Incidentally, Oksana Yakivna Meshko later told me how Sverstiuk wrote that piece.

The anniversary of Ivan Kotliarevsky was approaching in 1969, and Oksana Yakivna wanted to organize an evening in his honor. She needed a script for it. She turned to Sverstiuk. Sverstiuk wrote a long article. Oksana Yakivna looked at it, read it, and said: “It’s not quite what I wanted, but it’s exactly what’s needed.” And that article also circulated widely at the time.

There were other things. One piece was signed by Anton Koval—“A Voters Letter” by Anton Koval. It was about how our elections are conducted, about the so-called socialist democracy. I later learned that the author of this article was Vasyl Lisovyi. He says this now, but he didn’t say it back then. These were things like the text about the trial of Pohruzhalsky—that was also in my hands. Yes, *66 Answers to an Internationalist*—that was by Viacheslav Chornovil, or *What and How B. Stynchuk Argues For.* It is known that in response to Ivan Dziuba’s work *Internationalism or Russification?*, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine put together a piece titled *What and How Ivan Dziuba Defends*. But this response was so clumsy that they didnt even publish it in a large print run, instead sending it only through their Central Committee “comrades” to the directors of major institutions. It also fell into the hands of Viacheslav Chornovil, and he wrote his response. Also that well-known piece, *The Chornovil Papers*, about the 21 people arrested in 1965—I had that in my hands, too. I even remember the first copy with photographs glued in. Because it was all on a typewriter—there were no Xerox machines back then, so everything circulated in typescript.

I tried to read such things as quickly as possible and pass them on to my friends and acquaintances. I treated this matter very scrupulously, very responsibly, so as not to get myself, or Vasyl Lisovyi, or other people who gave me samvydav into trouble. There was a firm position here, on the level of self-awareness, that if you get caught, you dont say where you got it. Or at least you make up some story about finding it by chance. I was very serious about my friends and chose only those who behaved decently in everyday life, in small things—it was obvious that such a person would not betray you in something bigger. Apparently, I had a certain feeling for people, because no one turned me in over five years.

I basically started distributing samvydav with Vasyl Symonenkos diary, sometime near the end of 1967, and from 1968, it was at full capacity, starting with Ivan Dziubas work. I gave it to literally dozens of people. Of course, the vast majority of the students were Komsomol members, and some were even members of the Communist Party. Some were older people and teachers. I gave it to employees of the district newspaper in my hometown, and to relatives. Somehow, no one turned me in. And I managed to do all this for five years. I prioritized the distribution of samvydav. I had, of course, many obligations—I was a student and had to pass exams—but when it came to these matters, they always came first for me.

The beginning of 1972 arrived. Literally a day or two after those massive arrests, that big sweep, I heard that the arrests were happening, that Ivan Svitlychnyi, Nadiya Svitlychna, and a little later Ivan Dziuba, Oles Serhiyenko, Antoniuk, Vasyl Stus were already under arrest, as well as Chornovil, Shabatura, and the Kalynets family in Lviv, and Danylo Shumuk in Kyiv. In short, these names were very familiar to me; I had read their works in samvydav, and especially in the *Ukrainian Herald* these names were on everyones lips in our circle. So this hit me very hard.

You know, this situation is partially described in my book. Perhaps I can’t retell it now exactly as I wrote it, but there was this feeling that something had broken, that you were left all alone, that Kyiv had become empty. The only person left of my acquaintances was Vasyl Lisovyi, who walked around ashen-faced. And sometime around February, he told me that he was going to write an open letter in defense of those who had been arrested. He justified it by saying that it was unacceptable for everyone to remain silent. Someone has to declare themselves, someone has to say a word of protest. Let them not think that they have already purged Ukraine to the ground—its not so.

He started writing this letter, and he gave me the first draft to keep for a while. I kept it at my place and at my friend Petro Romkos, who lived in the village of Skybyn, Zhashkiv district, in the Cherkasy region. So Petro, without my permission, copied this letter by hand. He copied that first draft. And, by the way, that first draft has been preserved. I later returned the manuscript to Vasyl Lisovyi, and he finalized it. As I now know, Yuriy Badzio, who read it and made some comments, and Yevhen Proniuk also helped him. Vasyl Lisovyi took those comments into account. He also asked me to make some remarks, but my comments were very few.

I remember that sometime back in 1969, Vasyl Lisovyi told me something interesting: that as long as the national question is not resolved, this cause will draw all the best forces to itself. Look, he said, for example, you will become a philologist, study the phoneme in depth, describe it, while another specialist in radio engineering will a perfect listening device. And thus you will be working against yourself. Or, say, that Korolyov, a Ukrainian by birth, created a rocket. Who is it used against? Against us—against us, and for the benefit of the empire. So I, fully aware, went into it, knowing that we as a nation needed to achieve independence.

And I had a living example—Vasyl Lisovyi. He is a scholar, an academic, a man with a deeply analytical nature. And it would seem that it wasnt for him to take up political matters. But he does. He told me: “Of course, you and I could organize a demonstration together. It would last one or two minutes. Would that be effective? Who would see it? On November 6th or 4th, 1978, Vasyl Makukh immolated himself—almost no one knows about it. It’s clear that we need to distribute some texts that would have a certain influence on public opinion.”

So, he decided to write such an open letter, and he had a list he had gotten somewhere of prominent figures in literature, science, and culture, as well as in politics—people who held more or less loyal and democratic views. And we were supposed to distribute his letter after it was printed.

But let me touch upon the arrests of 1972 itself. That story is described in my little book, but I know some details that few people know about this case. As is known, just before the New Year of 1972, Yaroslav Dobosh came to Ukraine. He was a member of SNUM [ of Ukrainian Nationalist Youth], from Belgium, he was 25 years old, but he was traveling through Prague. And, I know that my classmate Anna Kotsur, who is a Lemko from Slovakia and studied with us in our department, went to Prague just before the New Year. She met with this Dobosh there, as I later learned. She gave him the phone numbers of Lviv’s—as we now say—“sixtiers” and Kyiv’s, including Ivan Svitlychnyi.

So, it was with these phone numbers that he called Svitlychnyi and someone else here in Kyiv, and later met with Svitlychnyi and other people. Thus, this Anna Kotsur provided the lead. I remember she was also detained, sometime around January, held under arrest for a few weeks, and then released. I remember how she came to the university, crying that she was being expelled. Then she was at the Czech consulate—and it’s strange, how could one hide in the Czech consulate in Kyiv. But she really did sit in the consulate for a few days. Eventually, they threw her out.

Later, when I was arrested, I read the testimony of Yaroslav Dobosh, and I came to the conclusion that he was probably an accidental figure. I am not sure if he was genuinely recruited by the KGB, or if he was just naively curious, or if he had some mission from his superiors—God only knows. But the KGB used him quite skillfully. He told everything he knew and didnt know, appeared on television with a statement, and that statement was published in the press. He was released, and all this became a pretext for mass arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. I remember that around February 12, *Radianska Ukrayina* and *Pravda Ukrainy* published a brief report stating that “in connection with the Dobosh case, and also for conducting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda in Ukraine, Svitlychnyi, Sverstiuk, Chornovil (his name was spelled with an o) and others have been arrested.” So, no one was incriminated with espionage—that fell away on its own. Dobosh was released after a few months, but the anti-Soviet agitation charge against these three and the “others,” behind whom stood dozens of people, all of that remained.

So, it was in connection with this that Vasyl Lisovyi signed his letter. At the very end, he writes—this letter was published in the eighth issue of the journal *Zona* in 1984—there it is written in black and white: “I am not involved in the so-called Dobosh case, but this is a living matter, directed against the Ukrainian people. And I am involved in this matter, and therefore it is unbearably difficult for me to be here while they are there. I ask to be arrested and tried along with them.” So, I helped Vasyl Lisovyi in making this letter. But a little earlier, Vasyl Lisovyi and Yevhen Proniuk, who also worked at the Institute of Philosophy, decided to produce the sixth issue of the *Ukrainian Herald*. The *Ukrainian Herald* had stopped with the fifth issue—it was halted in mid-1971 because rumors started spreading that arrests were imminent, and Nikitchenko himself had a conversation with Ivan Svitlychnyi and said: “As long as you were not organized, we tolerated you. Now that you have a journal, we will not tolerate you.” The decision was made to stop publishing the *Ukrainian Herald*, but it was already too late.

So, when these people were arrested, they were certainly accused of publishing this journal—which to some extent is an organization. The sixtiers tried hard to avoid any form of organization; everything was done on a friendly basis. Later, during our trials, the prosecutor Makarenko would lament: “They were great leaders of a small movement!” And you know, he was right—the movement was indeed small, but the leaders were truly great. These people were capable of launching a great national liberation struggle. For that, a little more time was needed, a few more years. And from the KGB’s point of view, the blow was struck at just the right time. Yevhen Sverstiuk once said that it was neither an organization, nor a party, nor any underground, but when so many glorious people come together, something will come of it. Something significant was indeed bound to happen. The KGB understood this in time, and they struck that blow at just the right time. Well, they thought they would have peace from the Ukrainian movement for 10-15 years, but they were mistaken, because in 1976 the Ukrainian Helsinki Group appeared, completely unexpectedly for them.

So, Vasyl Lisovyi and Proniuk compiled texts about those arrested—short biographical notes. We also had a text by Borys Kovhar, who at the time worked at the Museum of Folk Architecture here in Pyrohove. Incidentally, the KGB had sent this Borys Kovhar as an informant into the sixtiers milieu. But when he saw the kind of people he was dealing with, he essentially switched sides. And they took harsh revenge on him—they summoned him several times, then threw him into a psychiatric hospital and injected him with haloperidol there until he died. So, we had a letter from Borys Kovhar, addressed to KGB Major Danilenko—a devastating letter! We included it in that issue of the *Ukrainian Herald*. I performed technical tasks there—taking paper to the typist, buying paper, picking up the finished work, collating the sheets. You know, I remember when I received all ten prints of the sixth issue of the *Ukrainian Herald*—it was in Shevchenko Park, there by the university, behind Shevchenkos back. And I felt so distinctly that what was in my hands right then was the most important thing in Ukraine. This was sometime around March 1972—my last year of study at the university.

And so, the business with the letter. I took the letter to a typist, Raia, in Nemishayeve—that’s a train station in the Teteriv direction. I took her the letter, paper, carbon paper, and the text. She was supposed to type it within some agreed-upon time. Meanwhile, I was finishing university, and I had to leave the dormitory—I had to be out by the second of July. So I say to Vasyl Lisovyi: “Maybe I should really go home, to my place in the Zhytomyr region? But on the sixth of July, I’ll come, pick up the text, collate it, put it in envelopes, address everything, bring it to Kyiv, and send it to the appropriate addresses.” But Vasyl Lisovyi told me not to, that I should go home, that I had done my part, and they would handle it themselves.

And as I later found out, this is what Vasyl did: on the fifth of July, he submitted the typescript that he had himself—he had typed a few copies himself—he submitted one copy to the correspondence office of the Central Committee of the CPU. That’s the building where our President now sits. And he submitted the second copy to the director of the Institute of Philosophy, where he worked. Why did he do this? He saw that he was already being followed and that he might not have time to submit the letter officially. And he really wanted to submit it.

However, this is where the mistake crept in. Yevhen Proniuk went to Nemishayeve to pick up the letter. And on the way, I think at the Sviatoshyno station, they arrested him with that stack of paper—there were seventy copies printed on thin paper. They took him to the “Lenin room” at the Bilshovyk factory, searched him, drew up a report, and arrested him.

And on the sixth, Vasyl was called in to work. He went, and then they returned home with him, conducted a search, and that was it. Vira Lisova, his wife, was pregnant at the time, literally in her last days. She gave birth to their son Oksen on July 22, and this arrest takes place on July 6. Imagine the situation.

Interestingly, I was summoned to Kyiv by the deans office, supposedly to submit documents for graduate school, even though I knew I wasnt eligible—they had given me a C in scientific communism. They probably suspected that something was amiss with me, and to prevent me from applying for graduate studies in Ukrainian language, they gave me a C, so I wasn’t eligible. And so they call me, clearly so I would go somewhere, to see someone, and they could see where I was going. I only went to one woman, who was somewhat removed from these matters. She told me everything and said I shouldnt go anywhere. For some reason, they also sent me to the place where I was supposed to work—in Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi—to see if they would object to me studying in graduate school. How could they object? Nevertheless, I went there, and the wife of the school director where I was supposed to work met me with tears: “Oh, the KGB is looking for you!” This was on July 7. Lisovyi had just been arrested yesterday. For some reason, they were looking for me there too. Strange information. Just in case, I thought: let me rest a little. And from Pereiaslav, I didn’t go home but to the Cherkasy region to visit relatives. I stayed there for two weeks. And the KGB really didnt know where I was. Then I returned home—nothing, no one was looking for me.

Well, August came, and I went to work in the Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi district, in the village of Tashan. I work there at the school and, you know, this period was quite difficult for me. The living conditions there were not very good for me, and besides that, there was this constant expectation of arrest. They werent touching me yet, but now and then, rumors would reach me that they were closing in on me.

I mentioned Petro Romko, who, on his own initiative and without my permission, copied Vasyl Lisovyi’s letter. I made several clean copies of that letter using carbon paper and gave them to a few acquaintances, simply to preserve it. As for distributing it—I no longer knew who I could give it to. I gave it to a few acquaintances so that it would at least be saved. But I didn’t stop my work there—even in the village, I took the risk of giving things to read even to schoolchildren. I had ninth-graders, but you know, I was already under surveillance there too. It later turned out that one boy, Ivanko, couldnt keep quiet and showed it to the school’s academic supervisor, who in turn reported it to the KGB, and so I was already on their hook. And a rumor reached me that the supervisor had said I wouldn’t be there for long.

Or take this. Just before the New Year, I started teaching my students Christmas carols and щедрівки [New Years songs]. The texts were even altered; it wasnt the Son of God who was born, but the New Year. However, even the principal forbade that. In addition, I created a large display about Skovoroda. It was his 250th anniversary at the time, and I depicted a little church with a small cross on it somewhere. A Bible on the table—also a cross. I brought it to school. A few days later, the principal accused me of promoting religion. And I had to take it home. It was a very harsh conversation. In short, I didnt sit idle, not even there.

There I set about writing an article, as best I could, titled “Dobosh and the Oprishky,” with an alternative title “The End of the Sixtiers.” I wanted to make sense of what had happened in our society. I finished this manuscript and hid it in the cellar where I was living. But they flushed me out. I received a notice to report for two months of military retraining, supposedly. This was evidently done to make me move. I indeed took this text, took it to my sister’s in Kyiv, and hid it in a desk there, with the idea that from there I would go to my own village and leave the text there.

No, it didn’t work out that way. I think it was Saturday, March 3, when I went to Kyiv. There was a very suspicious person on the bus who tried to help me buy a ticket. I took the last ticket, and then for some reason he ended up in the middle of the bus. I shook him off in Kyiv. I already knew how to lose a tail in the metro. I stand right at the metro doors, and when they announce that the doors are closing, I jump in, and he’s left behind. Or, for example, to get out the same way—I stand by the doors and at the last moment, I jump out of the car, and he remains inside the car. In this way, by the way, I shook off that tail on March 3.

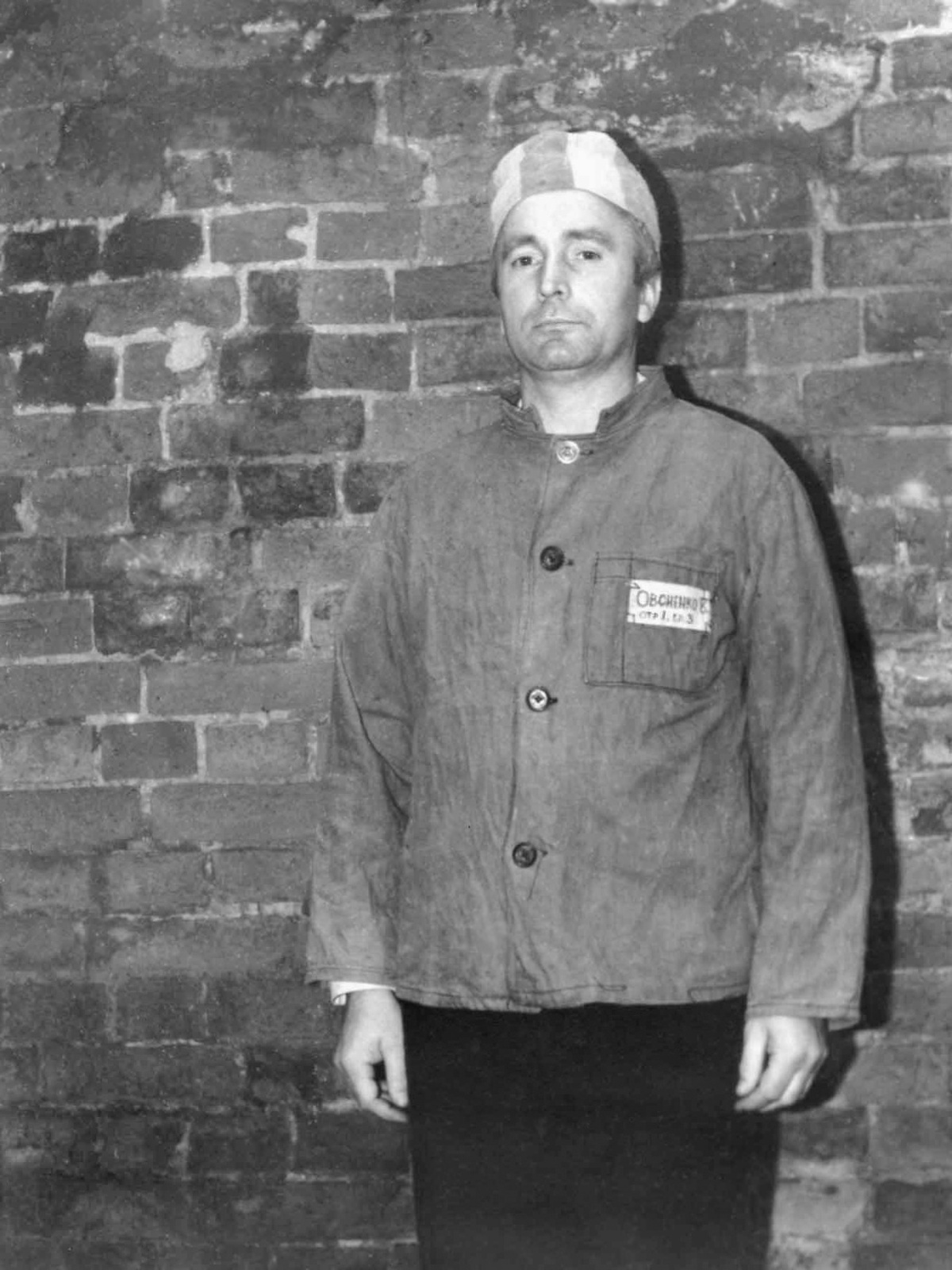

But I returned home on the evening of Sunday, March 4, got my papers from their hiding place, and wanted to work on them. I was too lazy to put them back in the hiding spot. And in the morning, they took me. As I was walking to work, a light snow had just fallen... By the way, it was a significant day—the twentieth anniversary of Stalin’s death, March 5. And a light snow had just fallen. Well, how much snow was there—a few centimeters. So, I’m walking across the common—this is in the village of Tashan in the Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi district—and suddenly two men: “Vasyl Vasylyovych!” — “What’s the matter?” — “A car is stuck, help us push it out!” Where could it be stuck—hordes of schoolchildren are walking there, and there isnt that much snow. Well, they approached me and suddenly—grabbed me by the arms: “We’re from the KGB.” I said: “I figured you were from the KGB.” I took it somehow calmly.

They took me to Pereiaslav, where there was an investigator… Ive already forgotten his name, he had a very Asian-sounding surname, and an Asian appearance. He suggested that I hand over everything anti-Soviet that I had. I said I had nothing of the sort. Then they put me in a car, took me back to the village, conducted a search, and found those manuscripts—they found them because they were lying out in the open! They brought me here to the KGB—not to the one at 33 Volodymyrska Street, but to the regional one on Rozy Luxemburg. They held me there until late in the evening, and in the evening they brought me to 33 Volodymyrska, to cell 51—I still remember it. And you know, I fell asleep there so soundly that they couldnt wake me in the morning—what a miracle!

But what I remember is that first search, how they searched me for the first time. They went through every seam, pulled the tips off the shoelaces from my boots and turned the laces inside out! I could never have imagined such a thing—how can you turn shoelaces inside out? Or a procedure like this: comb your hair, they look in your ear, in your mouth, tap your teeth with a pencil, then show your heels, then “spread your buttocks,” then show your glans. This makes a strong impression on a young person. At this, I remarked: “Oh! You’re like an ENT doctor.” — “Keep talking, just keep on talking!” the cop said. Things like that stay with you for a long time.

Well, during the investigation, I held out for a month and a half, giving no testimony. The case was handled by investigator Mykola Pavlovych Tsimokh. Not long ago, I found out that this Mykola Pavlovych Tsimokh now works in the administration of our illustrious Mr. President. After about a month and a half, he said a fateful phrase to me: “It is human nature to defend oneself, but you are not defending yourself. Some here doubt your mental competence.” I’ll tell you, I was genuinely scared. I knew what that meant—it meant they would throw you in a psychiatric hospital, pump you full of that haloperidol, and you would become a humanoid beast, not a person. At 23, that seemed terrifying to me, worse than death. And I started to give in little by little—it seemed they already knew some things. So I told them. It was no secret to them that it was Vasyl Lisovyi who had given me the samvydav to read, because they had that recorded back on November 3, 1972, that he had given me samvydav—they already had that.

Well, they still sent me for a psychiatric evaluation. The evaluation was conducted by a certain Natalka Vasylivna Vynarska. The entire criminal world knows her. It was the thirteenth ward of Pavlivka Hospital. I spent eighteen days there. But they no longer needed to declare me mentally ill, because I had already said something. And at the trial, I had to say that I admitted my guilt, that my activities, as they called them, had harmed the state and that I regretted it. Lisovyi held a firm position, and Proniuk an even firmer one—Proniuk made one statement at the beginning, and then all his answers were the same: “I understand the question, I refuse to answer on ethical grounds.” All of Proniuk’s protocols are like that. Well, Lisovyi gave some explanations. They didnt fully believe me, however, and gave me four years of imprisonment. And thank them for giving me those four years of imprisonment and not releasing me, because if they had released me, I would have felt broken, and probably the only thing left would have been to drink myself to death. That is the fate of such broken people. They sent me to be educated, and for that I thank them.

In the spring, on April 12, 1974, after a sixteen-day transport, they brought me to Mordovia, to labor camp number 19. This is the village of Lesnoye in the Zubova Polyana district. The camp held about 300-350 people. About half of them were Ukrainians. Many were convicted of so-called anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. Some of them shared a similar fate to mine, as they were inexperienced in such matters and had also lived through such a tragedy. In addition, there were about 10 members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army—people, you know, with exceptional biographies, very firm positions, and high morals. I say this very responsibly. For example, Ivan Syniak, who had a 20-year sentence, or Mykola Konchakivskyi, with 29 years, Roman Semeniuk—28 years. Then there was Volodymyr Kozlovskyi—25 years, Ivan Myron—25 years, Mykhailo Zhurakivskyi—25 years. These were men of legend. I became close with these people, as well as with our dissidents, and I recovered quickly. By the end of 1974, I was already taking part in the protest actions that were happening there, and in 1975 as well. The conditions of the regime are described in quite a bit of detail in my little book, *A World About People*—you can find information there. I had one short visit with my father there and another, longer one with my sister and mother.

From time to in time, people from the so-called Ukrainian public would come, led by KGB officers—academics or some tractor drivers. And they would have conversations with us. I remember that in one such conversation, I spoke with them very harshly. At that time, the female political prisoners who were in one of the Mordovian zones were on a long hunger strike. Iryna Kalynets was on a 100-day hunger strike, and the artist Stefania Shabatura as well. So when they, these representatives of the public, asked me what I wished for, I told them: “Return the materials that were taken from these women.” Their poems, embroideries, and drawings had been confiscated so they would end their hunger strike. —“Well, what if they like to starve?” At this I exploded and called them fascists, something like that. So on October 30, 1975, they took me out of that zone and transported me to another one in a village called Umor in Mordovian, or Ozyorny settlement. This was already in the Tenghushevo district—or maybe I’ve mixed up the districts? And October 30—that’s the Day of the Soviet Political Prisoner—on this day there’s a hunger strike, a statement of protest, things like that. I wrote a rather sharp statement then, which was later used in my next charge—that was the statement of October 30, 1975.

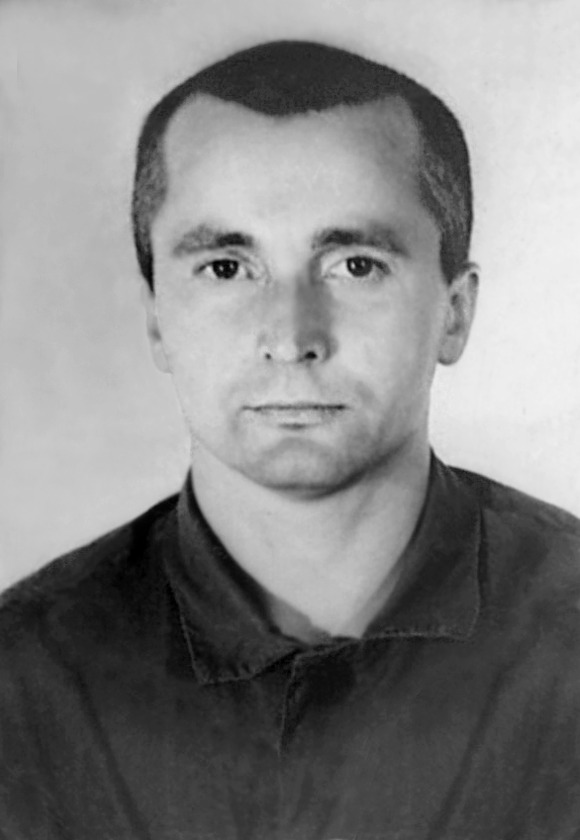

So, they brought me to this zone, and soon they sent me back to the punishment cell. Then, they brought Vasyl Stus to this zone. That was on February 6. On that very day, so that I wouldnt meet Stus, they snatched me out and took me to the hospital, and they kept me there until May 8, 1976. They performed an operation on me there for hemorrhoids—a common ailment for prisoners. So, it was only on May 8 that I returned to this zone number 17-A and met Vasyl Stus there. We spent several months together there. Actually, they took me to Kyiv again in the summer. I remember on June 9, 1976, they put me on a transport and took me to Kyiv for “brainwashing.” I spent two months on the road and then in the KGB prison at 33 Volodymyrska. They tried to have conversations with me, to set me on the right path, they arranged several visits, for example, they brought a university lecturer, and my relatives, but the result of all this was that on August 20, 1976, as I remember it now, I wrote a very categorical statement retracting my admission of guilt, writing that my confession had been the result of psychiatric blackmail, and that in reality, I did not consider myself a criminal in any way. Of course, they sent me back to Mordovia again, to the nineteenth camp.

I remember arriving at the nineteenth camp on September 11—Mao Zedong had died the day before, so I remember that date well. Vasyl Stus was there, Kuzma Matviyuk was there. Earlier, in that zone, I had been with Zoryan Popadiuk, Liubomyr Starosolskyi, Ihor Kravtsiv was there—from among the Ukrainians—Kuzma Dasiv, Arsen (or Artem) Yuskevych, and I mentioned the insurgents earlier. From non-Ukrainians—Sergei Soldatov from Estonia, his associate was there, Kronid Lyubarsky was there in that zone—from the Russians. Aleksandr Bolonkin was also there; later Osipov was brought (I was with Osipov for a short time, but I was). There were Armenians—Ashot Navasardian, Azat Arshakyan, Razmik Markosian; a Latvian, Maigonis Āviņš—a young, very frail boy of nineteen. There were more Lithuanians. Liudas Simutis—a respectable person. I also knew Petras Paulaitis—the same Petras Paulaitis who was Lithuania’s ambassador to Spain, Portugal, and Italy before the war. Among the younger Lithuanians there was Vilčiauskas—a very handsome guy—Vidmantas Povilionis, Romas Smailys—these were some of the younger guys. This was our circle.

From the Russians... You know, the Russians kept to their own circle. For the most part, these were people who held monarchist views. This was the circle of people arrested, I think, in 1969 in Leningrad. Among them were Averochkin, someone else was there, I can’t recall now. In short, these were Russian monarchists...

B.Ye. Zakharov: Were there any disputes?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: You know, when we held actions like hunger strikes or protests, this Russian monarchist circle generally did not participate. But we still communicated with them. And so this... Ah! I also have very strong memories of Mykhailo Heifets—that was in the seventeenth zone—who wrote wonderful essays about us. I hold this man in very high esteem—among all the people I know, he is one of the very best. This was the circle...

I was with Vasyl Stus in the seventeenth camp, then in the nineteenth. Vasyl Stus was actually taken from there on January 11, 1977. We even organized a final evening for him, brewed a large cauldron of tea. And on the eleventh, he was taken away on a transport.

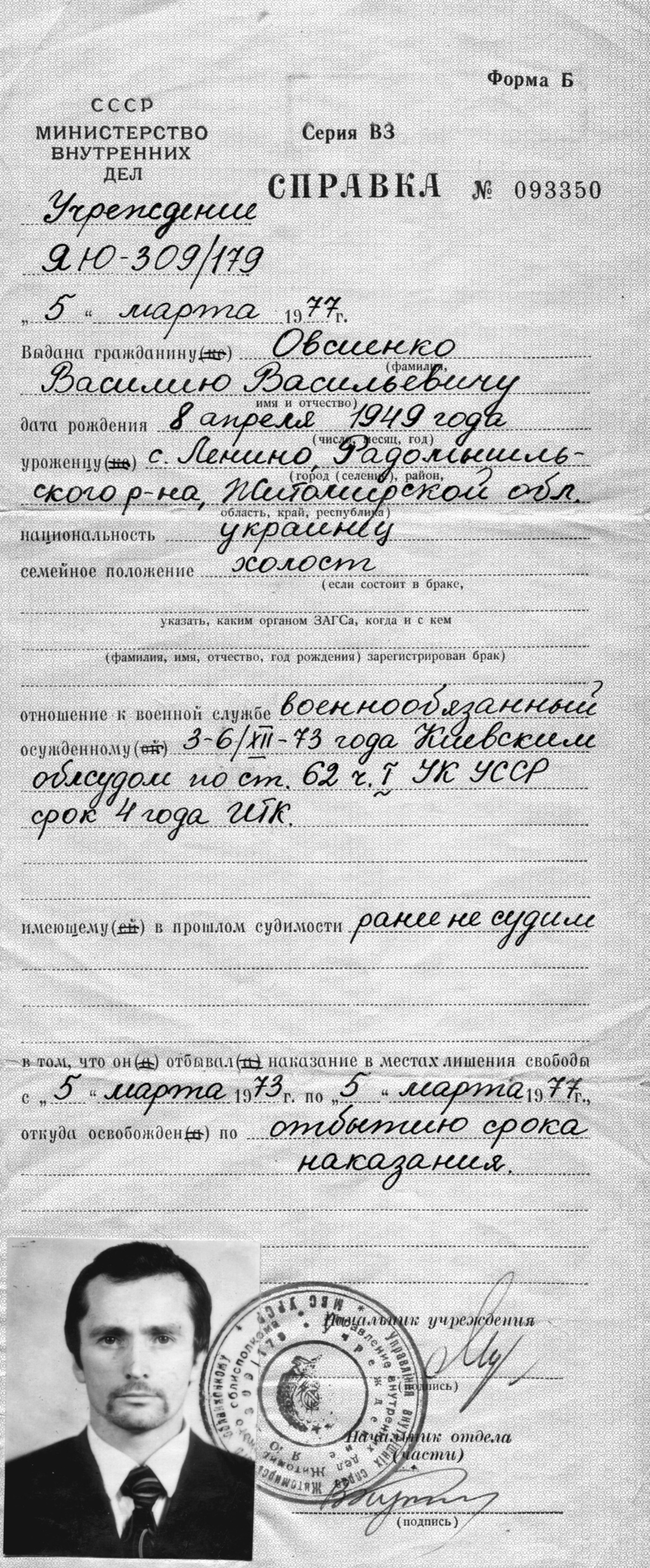

And I was taken from the Mordovian camp number nineteen on February 9. There was still almost a month left until my release. Why did they do this? They would transport you to your home region, release you there, and immediately place you under surveillance. Because a practice had emerged where a prisoner is released from Mordovia, Moscow is not far, he goes to Moscow, gives information about the latest events, and then the information spreads. So they started transporting us home—to be put under surveillance right away. They did the same to me. They held me there until the last day in the Zhytomyr prison and released me on the day of my release, March 5. They gave me strict orders. They bought me a bus ticket and told me to go straight to the police in Radomyshl, not home, and there they immediately presented me with a supervision order. That was it, I was on the hook—I couldn’t leave my house from ten at night until six in the morning, I was not allowed to travel outside the district, and I had to report to the police every two weeks. Thats what they set up.

So, under supervision, I had to get a job as a decorator-designer at the kolkhoz. Before that, I had tried to get permission to work in my profession—as a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature—but I received identical responses from the Ministry of Education, the district education department, and the regional education department, all saying that I had been dismissed for an immoral act—my conviction—and therefore could not be allowed to work in a school, and besides, there were no vacancies. Of course, that was a lie; there was a position—if not in this village, then in a neighboring one.

But I saw this matter through anyway. Of course, as soon as I was released, I informed Kyiv and Moscow that I was here and that information was available, which I had prepared in a manuscript. The first to arrive from Kyiv was Ilyin, I’ve forgotten his first name, perhaps Ilya. Ilyin, I think. At Osipovs suggestion, I passed on this information about the latest events in the camps, and this information, as I later learned, appeared in the *Chronicle of Current Events*, probably in issue 42 or 47, I never saw it myself. In addition, at the beginning of April, Mykola Matusevych—a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group—came to see me, along with his wife Olha Heiko-Matusevych, Oles Berdnyks daughter Myroslava, and Luba Kheina—she is now Myroslav Marynovychs wife. They also took the same text, I had made two copies, and they evidently used this text in the materials of the Helsinki Group.

In addition, I received a letter from Petro Hryhorenko, which was written... He wrote it in Ukrainian, with mistakes, admittedly: “It is good that you have declared your position at once.” And that is why you might find in some publications, particularly in that big book *The Ukrainian Helsinki Group*, that I was supposedly a member of the Helsinki Group from March 1977. We had no such agreement at that time that I would become a member of the group. But such information exists in some places, while I consider myself a member of the group a little later—from November 1978, when Oksana Yakivna Meshko came to see me.

So, Mykola Matusevych and Myroslav Marynovych were arrested on April 23, 1977, and of course, I began to be called in for questioning. I gave no testimony. They also questioned my niece Luda, who happened to have come from Kyiv that day and saw these people. She also gave no testimony. They intercepted my letter to this Luda, in which I instructed her not to answer their questions. Well, in short, they later interpreted this as pressure from me. But it was just advice on how to behave during an interrogation.

Sometime in September, I gave Olha Heiko a notebook with Vasyl Stuss poems. Her home was searched and this notebook was confiscated. In connection with this, I was summoned to the KGB in Radomyshl around September, and I thought they wouldn’t let me go. However, they issued me a warning that if I continued such work, I would be imprisoned. This was based on the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from December 25, 1971 or 1972—there is such a Decree. Thus I was already on the hook. However, information about me started appearing on Radio Liberty, and I heard it. I had a receiver and listened to Radio Liberty through all the jammers.

On January 7, 1978, I submitted an application to the OVIR [Visa and Registration Department] asking to be allowed to go abroad, because my only prospect here was imprisonment. It would be better to be in a foreign land and free than not in a foreign land and in captivity.

In addition, on November 18, 1978, Oksana Yakivna Meshko—a member of the Helsinki Group—came to visit me, along with Olha Heiko and Olha Babych-Orlova from Zhytomyr. She is the sister of political prisoner Serhiy Babych. Oksana Yakivna spoke with me about the fact that there was no one left to work in the Helsinki Group. I agreed to work in the Helsinki Group—we agreed that I would write a text about the situation of exiles, as I had such information from my extensive correspondence, and also about the situation of those under surveillance, like myself. I also corresponded extensively with them.

I indeed wrote such texts very quickly. But on that day, this happened. When we went out to the bus stop to send them off to Radomyshl and beyond, a GAZ-69 car drove past us. It drove about a hundred meters, then turned back, stopped next to us: “Who are you, and why are you here?” — “I am Oksana Yakivna Meshko, and who are you?” Oksana said to them, and Olha also took out her passport. They shoved us into the car without saying anything. “Get in, get in.” They took us to the village council, searched us there, separated us all into different rooms, and swore at us, of course. In particular, I refused to tell them anything—why were they treating me this way? Why, really? We hadn’t violated anything. Had we disturbed the public order, or what? In short, it was a very ugly incident. I refused to answer. Eventually, a policeman grabbed me by the collar and shoved me out the door. That was the event.

Well, as a gentleman, because women had been insulted in my presence, on December 1, 1978, I wrote a statement to the prosecutor’s office that several articles of the Criminal Code had been violated against us. The result came rather quickly. On December 8, when I next came to the police station to check in, my supervisor, Viktor Slavynskyi, who, by the way, was present when we were detained in the village, informed me with great joy that I was expected at the prosecutors office. I went to the prosecutors office, and there they announced that a criminal case was being opened against me for resisting police officers with the use of violence—meaning up to five years. I wrote my testimony by hand so that there would be no distortions. However, they let me go home that day.

I returned late, and that evening I finished writing about Mordovia—I had written a text of about 46 small pages. It was mostly about Vasyl Stus. I finished it that evening and hid the text. Well, of course, on that day I had been made to sign a pledge not to leave, and it was clear that I would not escape from these claws. I informed Oksana Yakivna Meshko and Olha Heiko about the trouble I was in.

The investigation didnt last long, just two or three interrogations. They blackmailed several of my fellow villagers to give testimony, and some of them signed something, which they later retracted in court. But it was enough for them that the policeman testified. Although the expert examination of the raincoat from which I had supposedly torn the buttons was done 29 days later, when they took the coat for inspection.

It was a comedy. The trial was on February 7 and 8, 1979. I had a good defender—Serhiy Makarovych Martysh, recommended by Oksana Yakivna Meshko. And in court, he proposed that the case against me be dismissed due to the absence of a crime and of the event itself, and that a case be opened against the so-called victim—that police captain, Slavynskyi. There was quite a large audience, and to great surprise, the trial was open. At the trial was Ihor Kravtsiv, who had come to see me from Kharkiv; he had just recently been released from surveillance and dared to come, which I value very highly. Lina Borysivna Tumanova came from Moscow. She was from Sakharov’s circle. She had a tape recorder and recorded the entire trial. She was later arrested, held for several months, diagnosed with leukemia, released, and died a month later. I received one letter from her while I was already in the Urals. So, this trial received wide publicity, and my last word was recorded and distributed in samvydav. It was quite sharp. But they gave me three years of criminal camp, and I was arrested in the courtroom on February 8, the second day of the trial.

They sent me to Zhytomyr, then from Zhytomyr to Vilniansk in the Zaporizhzhia region. It was a difficult ordeal. They held me with criminals, and on the way, those criminals stripped me bare, taking whatever clothes I had, even some of my notes. I had a Criminal Code—they even took that, which was a great pity. Well, in Vilniansk in the Zaporizhzhia region, it was very difficult for me at first to find any more or less normal people to communicate with among the criminals. But in the first few months, I received many letters, and then in the summer, it was as if they were cut off. That was it. Only from relatives and only from relatives.

I was held there only until September 5, 1981. Already in the spring of 1980, I was summoned for questioning in connection with the case of Vasyl Stus. I refused to say anything. The prosecutor of that Vilniansk district, Bykov, shouted at me: “Nationalists like you and Stus should be shot!” There was an investigator, Kraichynskyi, who interrogated me, and then this Chaikovskyi came from Zhytomyr and also questioned me in the case of Dmytro Mazur. Dmytro Mazur from the village of Huta Luhynska, Malyn district, in the Zhytomyr region—he was the Dmytro who had visited me several times. He had previously served a year, supposedly for parasitism. Of course, it was for political reasons, thats clear—he was a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature. He was the one who brought Lina Borysivna to the trial, he helped me a lot—so, of course, they imprisoned him too, and he got six years and five of exile, “like all normal people.”

So, when he was arrested, they tried to interrogate me as a witness in his case. I categorically refused—no testimony. Then, on September 5, 1980, they took me to Kyiv, moved me from there, and on the way in Kyiv, I met Yuriy Lytvyn—right here, in Lukianivka prison. And we spent ten days in the same cell. There was some kind of quarantine imposed, someone had gotten food poisoning—so it was only for the better, because we had such a good talk. Lytvyn really lifted my spirits, and I arrived in Zhytomyr in high spirits. I gave no testimony, but I submitted a statement in defense of the arrested Dmytro Mazur. Investigator Radchenko said: “You’ll stay in prison.”

And so that I wouldnt be too far away, they sent me not to Vilniansk, but to Korosten in the Zhytomyr region. I stayed there for several months, and then on June 9, 1981, a KGB investigator from Zhytomyr, Leonid Ivanovych Chaikovskyi, a major at the time, came and told me right there, while I was still in the camp: “It has been decided to open a new case against you.” Not because I had committed a crime, but simply because it had been decided! Why was it decided? Because I had been declared a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. This was done by Oksana Yakivna Meshko according to our agreement of November 18, 1978—from the day we met. And a member of the Helsinki Group was not allowed to be free: if his term was ending, they would start a new case against him. They did this to Mykola Horbal on the last day of his release. The same with Olha Heiko—she took two or three steps into so-called freedom. They release her, and theres a Black Maria waiting, she goes straight from the watchtower into the van—and they take her to the prosecutors office to start a new case. Such was the fate of these members of the Helsinki Group.

A few days later, in Zhytomyr, Chaikovskyi had a serious talk with me and suggested I write a repentant statement for the regional newspaper, and then they would release me even before the end of this criminal term. I thought it over and chose 10 years of imprisonment and 5 of exile. Following Yevhen Proniuks example, I gave no more testimony—I made a statement at the beginning and another at the end. At the trial, I gave some explanations. The investigation was short. Chaikovskyi said: “We’ll gather enough.” “Enough” turned out to be my statement from October 30, 1975, written in Mordovia. It was addressed to the UN but dropped into the box “for complaints and statements,” meaning it was handed over to the administration. The second statement was in defense of Dmytro Mazur, handed to a KGB agent across a desk. And only one text of my last word was found in Dmytro Mazur’s possession, and no one else had read it. Nevertheless, all of this was called “the production, possession, and dissemination of anti-Soviet literature.” This means there was no actual dissemination.

B.Ye. Zakharov: Was that Article 57?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Oh no, no! Article 62, part two. Well, and of course, they brought in many prisoners who testified partly to things I had said, and partly to things I had never said at all. They had a poor understanding of my worldview. Well, accusations like, for example, “called Sakharov a great man of our time” (a great crime), had spoken somewhere about the occupation of Afghanistan, about the famine of 1933—that was also a “slanderous fabrication.” Things of that nature. Well, they didnt mince words this time—10 years of special-regime camp, 5 years of exile, and the title of a particularly dangerous recidivist.

The trial was on August 26, 1981—it lasted three days, ending on August 26. They transported me for 36 days from Zhytomyr to the Urals, via Kharkiv, Sverdlovsk, Chelyabinsk for some reason, and then Perm, and then they brought me to Kuchino. I arrived in Kuchino, Perm Oblast, Chusovoy district, on December 2, 1981. There, as I found out a few days later when they moved me to cell 17, were already Vasyl Stus, Levko Lukianenko, Ivan Kandyba, Oles Berdnyk, Oleksa Tykhyi. Then they brought Yuriy Lytvyn, Mykhailo Horyn, Valeriy Marchenko. Vasyl Kurylo was already there, Semen Skalych; Ivan Sokulskyi was brought later. These were the Ukrainians. From the Russians, there was Leonid Borodin, Yuriy Fyodorov from the “hijackers,” Oleksiy Murzhenko from Kyiv was there, also one of the “hijackers.” From the Lithuanians, there was Viktoras Petkus, Balys Gajauskas. There was a Latvian, Gunārs Astra. Later they brought Ashot Navasardyan and Azat Arshakyan—they were Armenians. Prykhodko was brought from prison later.

Overall, the contingent there… it was mostly Ukrainians, for the most part. There were a few people sentenced for war crimes—policemen, also mostly Ukrainians. There were a few politicized criminals who made our lives difficult, because they were used as provocateurs.

The regime there was very harsh, a cell-based system, one hour of walking in a yard three by three meters, lined with iron and with barbed wire on top. The searches were exhausting—sometimes you would be searched several times a day. You werent allowed to keep more than five books in your cell—books, magazines, and pamphlets combined. The food, of course, was bad. The work—we had to screw these small panels onto cords for an iron. I still have these parts. They kept us in cells with several men. I went through several cells there—the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth, twentieth. In particular, I had the chance to be with Vasyl Stus for a month and a half in February-March 1984. I saw his notebook, sewn together from several school notebooks—“The Bird of the Soul.” This was the bird that never flew out of there. And I am the only one who read those poems, including Vasyl Stuss translations of Rilke, eleven elegies—they too were probably destroyed. I could talk about this in great detail.

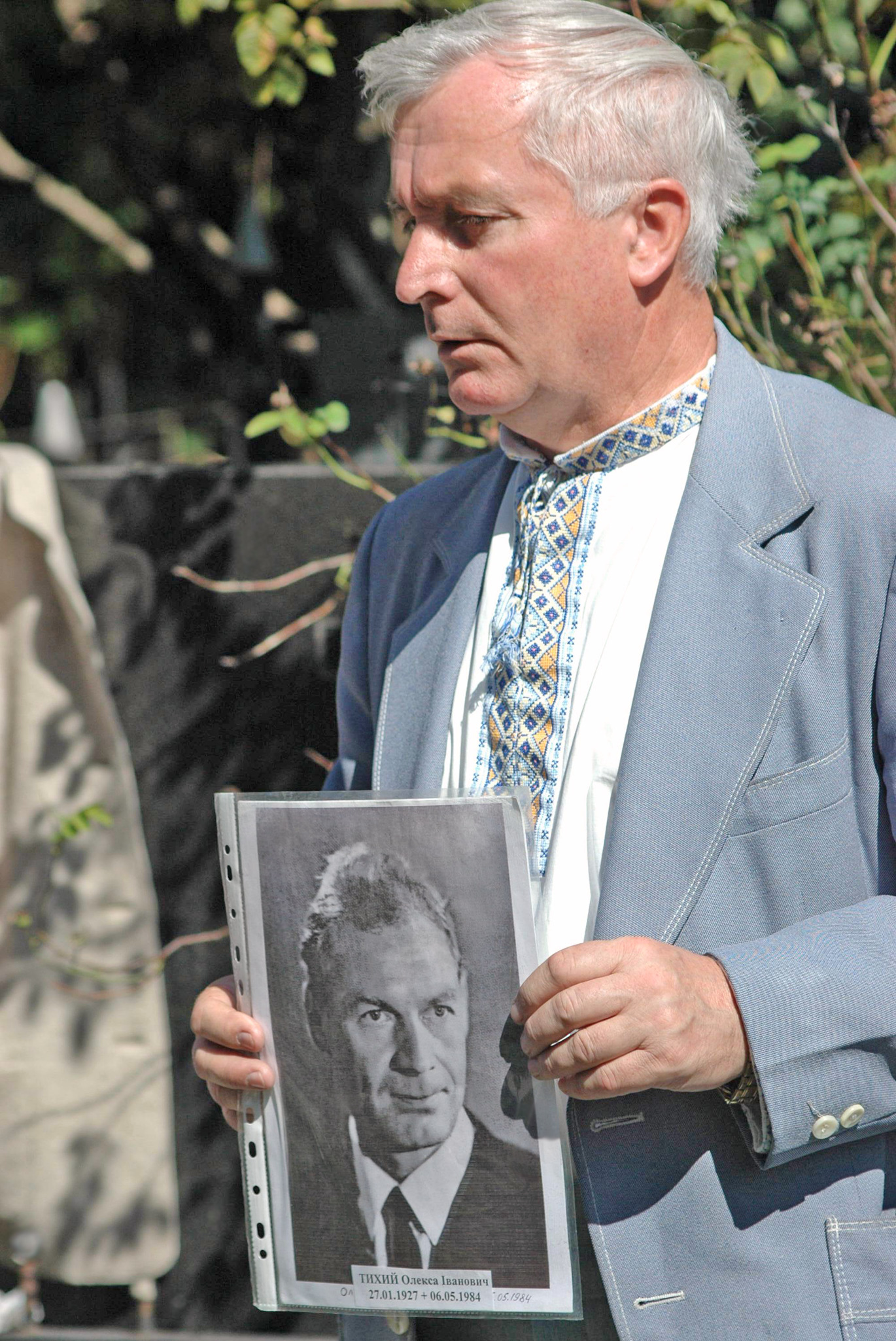

The regime there was so unbearable that people were dying one after another. In 1983, Mykhailo Kurka died. This man was older, already almost seventy. In 1984, Ivan Mamchych from Myrhorod, sentenced for collaboration with the Germans, died right in the camp, in the kitchen. On that same day, as we later found out, Oleksa Tykhyi, who had been taken from our camp in March, died in Perm in his fifty-eighth year of life; that was May 5. In 1984, they brought Valeriy Marchenko to us, thirty-seven years old, who had previously served six years, and now he had nephritis. He spent only about two months in the camp before they took him away on a transport. We later learned that he died in the camp, or rather in the Leningrad hospital “Gazy,” as the prisoners call it, on October 7, 1984.

Yuriy Lytvyn. He had already undergone two stomach operations and one operation for varicose veins. And here he had another stomach ulcer, they filed his teeth, removed the enamel and did nothing. He lived his last nine months without enamel. So, he probably couldn’t take it anymore, and on August 23, 1984, he was found in his cell with his stomach slit open. Although I cannot assert that it was a suicide—there are some grounds to believe that they may have arranged something for him. He was found by the prisoners. They came for lunch, Yuriy Fyodorov removed the blanket and saw that his stomach was cut open. And he was delirious: “Did they bring the teeth?” Well, they took him away, took him to the hospital. The operation they performed was poor, his stomach began to swell, so they did a second operation, and he died on the fourth or fifth of September, in his fiftieth year of life.

And so everyone began to wonder whose turn was next. There was an Azerbaijani man there, Akper Kerimov—such a gentle and good-natured man, also accused of collaboration with the Germans. He suffered terribly from his kidneys. They took him to a hospital in Vsesvyatsky, and he died there on January 19, 1985. So everyone was thinking, whose turn is next.

Well, it turned out to be Vasyl Stus’s turn—perhaps because he was the only one who managed to send his notes, which were called “From the Camp Notebook,” out into the free world. Nadiya Svitlychna published them. He had also been nominated for the 1985 Nobel Prize. Heinrich Böll, a Nobel laureate, had nominated him. As is known, this prize is awarded only to the living, not posthumously to the deceased. Once, when Adolf Hitler found out that Carl von Ossietzky, his prisoner, had been awarded this prize in 1936—he ordered his release. But Gorbachev did not want a Nobel Prize laureate in his cell, and he certainly did not want to release one. And so, a series of punishment cells, and specifically on August 28, he was accused of lying on his bunk in his outer clothes and “engaging in an argument with the citizen guard” when reprimanded—punishment cell. So Vasyl declared a hunger strike and never came out of it—he died in the night between the third and fourth of September in punishment cell number three in that very same barrack.

The regime did not soften after that. Consider that this was already perestroika, Gorbachev was already on the throne. But from 1986, it began to soften a little. Then in 1987, they transferred us from Kuchino—that was on December 8, I remember the date because on that day Levko Lukianenko was sent into exile, his term was ending, and besides, Gorbachev was meeting with Ronald Reagan in Reykjavík. And Gorbachev said there that we were no longer in Kuchino.

Indeed, they moved us from Kuchino to Vsesvyatskaya, but the regime there was already much lighter. KGB officers from Moscow began to court us—“write something, just anything—that I was mistaken, that I won’t do it anymore, that I’m at least sick, or let my relatives write.” We in the special-regime section dug in our heels, we wouldn’t write anything. Youre in a bind? You need to have a human face? Well, then have one: release us, take us as your allies, because we too are for perestroika. No, nothing of the sort! They started releasing us in 1988—one by one, two by two, they transport us to our home regions and announce our release there.

When they took me, Mykola Horbal, and Ivan Kandyba on a transport on August 12, 1988, only two remained after us—the Estonian Enn Tarto and Mikhail Alekseyev, a Russian who had been arrested in the Zhytomyr region. So, they took us to Perm. And on the night of August 21, they took me on a transport, the first of the three, on a plane, with a special convoy, a soldier here, a soldier there, and an officer here, handcuffs at the ready, but they didnt put them on this time. They had transported me twice before, and then they had put on handcuffs before boarding the plane. This time, we did without.

They brought me to Kyiv. We were chasing the sun—the sun was constantly rising as we flew to Kyiv, to Boryspil. And they held me there for several hours in some hole, while they themselves were trying to phone—because it was a Sunday—phone the KGB to send a Black Maria. They didnt send a van. Finally, they did, they brought me to Lukianivka—Lukianivka wouldn’t take me: “Take him to the KGB.” They took me to the KGB—the KGB accepted me. But these young soldiers didnt want to linger here; they needed to deliver me to Zhytomyr. So they managed to get a van, and they drove me to Zhytomyr in a van. We got there around one o’clock in the afternoon, in Zhytomyr.

And so they released me. You know what thats like? In a miraculous way, in a single day, you suddenly find yourself free! They even bought me a bus ticket, and I arrived in Radomyshl around eight in the evening. A taxi—a KGB agent gave me a ten-ruble note, I initially refused, but then took it—I gave that ten to a taxi driver, he drove me home, and by about half-past eight in the evening, I was home. Just the night before, I was, as Taras Shevchenko said, “from darkness, from stench, from captivity”—and in less than a day, I was free. It was truly a kind of miracle.

But look at what was written there. I asked to see the basis for my release, and it said: “Pardoned for good behavior and work.” As if I were a hooligan or some kind of idler. Pardoned! They were pardoning us, you see!

B.Ye. Zakharov: What was your activity after the camps, during the time of independence? What is your attitude toward the new Ukraine and your predictions for the future?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Right away, on August 23, I went to Kyiv and was already at a meeting of the Ukrainian Culturological Club, there at 10 Olehivska Street, at Dmytro Fedorivs place—that’s where the club used to meet. And on September 3, I believe, I gave my first truly free public speech, in that very same club. It was the eve of the anniversaries of the deaths of Yuriy Lytvyn and Vasyl Stus—they died on the same day, basically, just a year apart, one in eighty-four and the other in eighty-five. So, I read poems there, spoke about these people.

Then, in the Zhytomyr region, there wasn’t a single member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, which had resumed its activities at the end of 1987. Its programmatic and statutory principles were published on July 7, 1988. So I was authorized to be the Helsinki ’s representative in the Zhytomyr region. We managed to gather a few people over those several months. And on July 16, 1989, we held the founding meeting of the Zhytomyr branch of the Ukrainian Helsinki in Zhytomyr. I was elected chairman there. I had to go to work at the kolkhoz, working again as an artist, but every Saturday and Sunday I would travel somewhere—either to Kyiv or to Zhytomyr. It was, of course, burdensome, but I couldnt move anywhere, because my mother was alone.

So it was a period of turbulent activity. In particular, I had to go to Estonia in April 1989 with Levko Lukianenko and Yevhen Proniuk for the Conference of Democratic and National-Liberation Movements of the Soviet . I was at that conference, and I also went to Armenia, but the conference there didn’t happen—Ivan Sokulskyi and I went there—the conference didnt take place because the situation there was so tense.

I was a member of the Coordinating Council of the Ukrainian Helsinki , and when it came to creating a political party on its basis, I had no choice—Levko Lukianenko insisted that I move to Kyiv and become one of the secretaries of the Ukrainian Republican Party. The founding congress took place on April 29-30, 1990. It was the first political party in Ukraine. I was elected secretary there, and I was secretary of the Ukrainian Republican Party until October 14, 1996—six and a half years.

This is a very big job. I had to manage publishing for the URP, and many brochures were published through my efforts. We published an information bulletin, the newspaper *Samostiyna Ukrayina* (Independent Ukraine), in which I took an active part, and an almost weekly secretariat circular—that was also the fruit of my hands, so to speak, of my labor.

In addition, since 1990, I have been the co-chairman of the Ukrainian Committee “Helsinki-90.” The fact is that after the creation of the party on the basis of the Helsinki , there was no longer a Helsinki-style human rights organization in Ukraine. So, Oksana Yakivna Meshko, thank God for her, decided that such an organization should exist—because others would take its place. And the founding meeting took place on June 19, 1990—hence “Helsinki-90.” At first, Vasyl Lisovyi was the chairman, and then we elected three co-chairmen—me, Lisovyi, and Yuriy Murashov. So I am also involved in these matters.

In the Society of the Repressed, I don’t hold any official positions, but I have to do a lot there as well. Now, about the recent events in the Ukrainian Republican Party, which actually began back in 1995 when the leadership was changed at the insistence of Levko Lukianenko—I saw that things were not right in this party and from time to time I criticized not so much the activities but the inaction of the new leadership. And they didn’t like that. In particular, at a meeting on October 13, 1996, I delivered a rather sharp criticism of the new URP leadership headed by Yaroshynskyi, calling it inactive and one that repeatedly violates the statute and departs from the program—so, of course, these conversations spread, there was a discussion in the organization. And of course, after the congress, which took place on December 14-15, I was no longer proposed for any positions. And since I continued my criticism, on February 19, they expelled me from the URP—just like that. And on March 15, Mykhailo Horyn, Mykola Horbal, Mykola Porovskyi, Bohdan Horyn, and Oles Shevchenko were also expelled from the URP. Levko Horokhivskyi had suspended his membership even earlier. Thus, of the founding members, only Levko Lukianenko and Yevhen Proniuk remained. Well, Proniuk wasnt at those meetings, but it’s strange to me how Levko Lukianenko could raise his hand to vote for the expulsions. Well, that’s that.

Now, as of February 1, 1997, I have been working at “Memorial.” I havent been assigned a specific position there yet, but obviously, I should be a member of the executive committee of “Memorial,” which is headed by Les Taniuk, and this “Memorial” is named after Vasyl Stus. This is a great responsibility. I see that I need to concentrate on this work, because there is much to write, much to publish. Several books are already being prepared there, these books are being edited. And obviously, I say this, I dont regret that I was dismissed from those positions, because I am not really a politician—I am a philologist, and even in politics, I worked as a philologist, meaning I was involved in publishing.

So, the KGB...

...There was once a historical necessity to be involved in politics. The KGB drew me into politics at a young age, and I conscientiously engaged in politics until now. But the main thing I needed was freedom of speech. I say this categorically: freedom of speech exists, let no one complain that there is no freedom of speech. No one is grabbing anyone for their words. You don’t have the opportunity to get published, to publish a book? That’s your problem—you don’t have money, but you do have freedom of speech. Go stand at an intersection and say what you want, write what you want by hand, type what you want on a typewriter. So I have things to say, things to write, things to publish—I need to do this, I need to take advantage of this. Let other people engage in politics.

I’ll also recall another aspect. Soon after I was released, a movement began in Ukraine to bring the mortal remains of Vasyl Stus, Yuriy Lytvyn, and Oleksa Tykhyi back to their homeland. I took a very active part in that. In particular, during the first expedition, we were in the village of Kuchino on August 31, 1989, and on September 1, we filmed the cemetery where Vasyl and Yuriy were buried. I believe it was a good thing that was done, but they didn’t allow us to transport them—we were warned that the sanitary-epidemiological situation was unfavorable. That wasnt true, of course, but we did this reconnaissance, we filmed it, and this material was used in Stanislav Cherniilevskyis film *A Black Candle on a Bright Road*—he’s an old university friend of mine. What’s interesting is that after our departure, that KGB gang swooped in there with bulldozers and destroyed all the restricted zone markers, tore out the windows, the locks, ripped out the bars. And now our footage is very valuable, because starting in 1993, the Perm Memorial began to rebuild it all and a memorial there to the victims of political repression. This is intended to be a site of world significance. They are truly dedicated people, and its fortunate that in this particular area, people were found who understood the value of this site—it’s the last political labor camp. So they preserved it, they are rebuilding it, and they are creating a museum there.

So I am also doing a lot in this matter, we cooperate with these people. I have been there twice already. They hold a scholarly conference there every year. They have already opened this museum. I believe this is a noble cause. And if they used to talk about the “hand of Moscow” in Ukraine, then I believe this is our hand in Russia, because we need to educate Russians to be human beings too. To have a good, normal neighbor, we need to work for two hundred years—and then we will have normal neighbors, and we will live peacefully with them.

B.Ye. Zakharov: If you could briefly define the terms “the Sixtiers movement,” and “dissident” separately?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Yes, the Sixtiers movement, dissidence… The people actually started calling themselves “Sixtiers” around the late sixties, but half-jokingly. The term became firmly established much later, clearly associated with that generation. At first, it was written in quotation marks. There’s a well-known analogy with the “men of the sixties” of the last century in Russia. Well, I believe this period covers the time from about 1956, starting with the 20th Congress of the CPSU, when the cult of personality of Stalin was criticized.

In Ukraine, it first manifested in literature, of course—in poetry. Some also count Dovzhenko’s last works as part of the Sixtiers movement, to some extent, but he died in fifty-six. It also includes the first little books by Lina Kostenko, Mykola Vinhranovskyi, Ivan Dziuba, the first articles by Ivan Svitlychnyi, Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk—this was the late fifties—the poems of Vasyl Symonenko from the late fifties and early sixties. Vinhranovskyi—this generation clearly emerged in the early sixties. The year sixty-two—that was literary dissidence, so to speak, but there was also dissidence of a distinctly political nature. Most likely, it started in Lviv—with Mykhailo Horyn, who actively distributed samvydav literature of a political nature starting in 1962. For instance, *The Derivation of Ukraine’s Rights*—a book published abroad, and here it was photocopied. Or even Ivan Franko’s work critiquing Marxism, *What is Progress?*. Then came works of an economic and cultural nature—most of this was done under the leadership of Mykhailo Horyn—from Lviv, from there. It was in 1962 that Ivan Svitlychnyi, Ivan Dziuba, and Ivan Drach came to Lviv and met with the Horyn brothers and others. So that’s where it began.

Well, and a term like “dissidence”—that term was imposed by the West. No one called themselves a dissident in this society, because practically everyone you talked to was dissatisfied with the state of affairs. In fact, those who shared the official views were in the minority, and everyone else was a dissident. But this term was imposed—dissent, so to speak. It was imposed from the West, and it has stuck to some extent.

Yes, one can identify certain milestone moments. There was August 25-26, 1965—the arrest of 21 Sixtier-dissidents: the two Horyn brothers, Hel, Svitlychnyi was also arrested then, Zvarychevska, Anatoliy Shevchuk in Zhytomyr, Sviatoslav Karavanskyi in Odesa, Valentyn Moroz—well, you know these names.

The second wave was the arrests of 1972. That was essentially the end of the Sixtiers movement. The next wave was the Ukrainian Helsinki Group—that was 1976 and the following years. This was a distinct phenomenon in our society. Well, then one must count, if we are already in perestroika, the Ukrainian Culturological Club began its activities in Kyiv in 1987. In Lviv, around the same time, I believe there was the “Lviv Community”—or what was it called? Something like that, in Kyiv and in Lviv. Then, at the end of eighty-seven, on December 30, the resumption of the Ukrainian Helsinki Groups activities was announced. In March 1988—a more distinct statement, and the list of members was announced. On July 7, 1988, the Declaration of Principles of the Ukrainian Helsinki was announced, as well as its statutory principles. It then grew very actively—by the time of the Founding Congress, there were 2,300 people in the Helsinki , and it became a political party. That was the beginning of political pluralism in Ukraine; it was the first political party. It was registered later, on November 5, 1990, but it had been operating for six months when the CPU existed, which was not registered. We had the first registration number in the URP. That’s how it is, if we are to speak about the stages.

Of course, many other political organizations arose, and they also played a prominent role, particularly the Rukh [Popular Movement of Ukraine]. It was we, the Helsinki members, who actually created the Rukh—we were, so to speak, the right wing of the Rukh—the Ukrainian Helsinki . By the way, it was the Helsinki that sent Mykhailo Horyn to the Rukh, and he was the head of the secretariat there; he played a decisive role.

B.Ye. Zakharov: How would you define the role of samvydav in the changes in Soviet society?

V.V. Ovsiyenko: Well, the circle of people who read samvydav was not that wide. But these people spread the word that was in it. It seems to me that its role was absolutely exceptional in that society, and the exceptional significance was that these people acted openly—openly, without hiding their names. At least, on the surface, there were names that were not hidden, while underneath there was a bit of an underground, so to speak, a reserve—where and who produced the samvydav, that was hidden. And you know, this dissidence had an immense moral advantage over the regime—it fought with its visor up, these were not underground fighters. Because if they had been underground fighters, they would have been exposed, secretly tried, and this would have had no impact on society. I always emphasize this moral advantage of the movement.

Finally, Ill give an example. The same Levko Lukianenko was brought here to Kyiv in 1969 for “brainwashing,” and he had a conversation with General Gladush—the deputy head of the KGB. The first thing he did was express regret that Lukianenko hadn’t been shot in 1961, then he said: “What is there of you, you nationalists—how many of you are there? Some fifty people in all of Ukraine!” “Yes,” said Levko, “maybe there really are fifty people in Ukraine. But if even I alone remain a conscious Ukrainian, then Ukraine still exists.” And from that handful, as Vasyl Stus so beautifully said, *“There are few of us, a tiny pinch, only enough for prayers and constant waiting,”*—so, from that pinch grew a great Movement. It truly grew from just a few people in, say, 1957... or 1987! It began with literally just a few people.

And now, thank God, a whole generation has grown up under the yellow-and-blue flag, and you can’t just push it aside. So our cause, as you see, is winning. I am not such a pessimist, you know, like some people who would like very rapid changes. I know this: we were brutally destroyed, and the best part of us was annihilated. This satanic selection continued from 1918 until recent times. The best part of our population was destroyed, and in its place all sorts of alien, foul-mouthed riff-raff was brought in. And now try to educate a people, to form a nation from this mass of people! It will take decades, dozens of years are needed! And the fact that it is happening so slowly is completely understandable to me.

If you take the 1920s, what a powerful national revival there was! Because that was a Christian people, not annihilated, alive, healthy—just poorly literate. They were given an education—and it erupted in such a renaissance. Such an explosion happened in the twenties, and it was all destroyed.

And now—what is there to revive from? There is nothing! We have been annihilated, and therefore this new generation must be educated. It will grow, slowly. There is that idea about forty years in the Holy Scripture—we need those forty years, no less.

There is another example. In Galicia, before the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and the OUN could be formed, the “Prosvita” society worked for seventy years. We also need to work for that long. So there will be enough work for our lifetime. And I am trying to work in this direction.

B.Ye. Zakharov: Thank you very much.

Photo from the archive of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group.