According to experts’ estimates, from the early 1920s to the end of the 1980s, almost one and a half million people were arrested in Ukraine. On May 19, Ukraine commemorates the victims of political repression. We are publishing an interview with Kharkiv resident and human rights activist Ihor Lomov, who was sent to the Mordovian Dubravlag as the “ideologue of an anti-Soviet group.”

Ihor Hryhorovych Lomov was born in Kharkiv, studied at Lviv University, and worked as a history teacher. He was arrested in 1963 while he was a graduate student at the Moscow Institute of International Relations. This was the time of the so-called “Thaw,” the beginning of the human rights movement in the USSR, when mass arrests were not happening, but the repressive apparatus was working efficiently.

- Do you remember the day of your arrest?

- It was a Sunday, I had left the dormitory and was heading to the public transport stop. A figure appeared in front of me, walking with a waddle. I looked back, and another one was walking behind me. At first, I thought I was going to be robbed. It was winter, the snowdrifts were high… I thought they were about to throw me into the snow. But they said to me: “We need to go to the police station to check something.” A “Volga” was parked nearby. We got into the car and drove off. I saw we weren’t going the right way. I asked: “Which police station exactly?” And they answered: “Well, we need to stop by the administration office now to sort out some formalities.” And so we arrived at Lubyanka.

- Did you expect to be arrested?

- I had no reason to be afraid. But it turned out that a listening device had been installed in my room, and all conversations were being recorded. And my friends used to visit me. But I knew nothing about it...

- Do you have any idea why they started monitoring you?

- The thing is, there really were anti-government conversations. But the pretext for the arrests was the assassination of Kennedy… It was being actively discussed. They held a wake for Kennedy... And then people started saying that Nikita should get the same treatment. One person said it, another added that he would get rid of Nikita too. Well, and basically, I think that's when it all unraveled. At first, we were accused of creating a terrorist group. And when that didn't work out, the KGB just started investigating who said what, who had what notes.

- It was the Thaw. Did you imagine something like this could happen to you?

- The investigator also asked me if I wasn’t wary. But at the time, I thought the maximum punishment I faced was expulsion from the institute.

- Where did this dislike of Khrushchev and the jokes about his assassination come from?

- By the end of his career, Khrushchev was already arousing resentment, acting arbitrarily. It’s about what came to be called voluntarism. This caused irritation. He imposed his “vision of the beautiful” on the intelligentsia.

- How many people were arrested with you?

- The other two who had talked about Nikita. And a few were simply expelled from the university.

- And you were given five years of imprisonment? Did you also threaten Khrushchev?

- I didn't say anything like that, but they found my notes and convicted me under the article on agitation and propaganda. I ended up in Mordovia, in Dubravlag. There were several colonies there where people convicted of treason, policemen, Beria's men, those under the “Propaganda or Agitation” article, and Jehovah's Witnesses served their sentences. A colorful company. But there were no “common criminals.” There was an industrial zone, a woodworking plant. We made furniture, cases for radios. The production was well-organized: a sawmill, a drying shop, an assembly shop. They say that back during World War I, there was a camp for Austrian prisoners of war in Mordovia. Then enemies of the people, their wives, and their family members were imprisoned there. And after World War II, came the Banderites, Vlasovites, and Baltic nationalists.

- Was there communication between these groups?

- Mostly, people stuck together based on nationality. The Balts, for example... The Russians and Jews from Moscow and Leningrad—the “general democrats”—tried to establish contact with them. But the Balts showed no hostility, although they kept to themselves. The Galicians were the same. Later, people started being brought from Kyiv. And they didn't really contact us, the “general democrats,” either. Although I did talk with the Horyn brothers and Moroz. At the same time, Shukhevych's son, Yuriy, was serving his sentence in the camp. He mostly talked with old Banderites, those who might have known his father. Yuriy Shukhevych was quiet, I never heard his voice. Unfortunately, he later fell ill and went blind. But I did converse with some members of the Ukrainian underground. Especially since I had learned the Galician dialect when I was teaching in the Lviv region.

- What were the living conditions like in the camp?

- It was a strict regime. Sections for about forty people, bunk beds… The food: borscht and kasha—that was our meal. Sometimes they gave us khamsa [a type of anchovy] to prevent scurvy. I remember when one of the Jehovah's Witnesses was offered a job in the kitchen, they would set a condition: either the entire shift would consist of Jehovah's Witnesses, or none of them would work in the kitchen. Because things were stolen in the kitchen, and the Jehovah's Witnesses didn't want their reputation to be tarnished. They are very honest people.

- Was a lot stolen?

- I had a friend, a Kazakh from the philosophy department, a very principled man. He told me that one evening he was walking past the mess hall. Suddenly, a worker runs out, shoves a package into his hands, and disappears. My friend unwraps the package, and there's meat inside. Meaning, the mess hall worker had mistaken him for someone else. People stole on the outside, and they stole there too. Everyone got by as they could. There were those who took the “pridurochni” [cushy] jobs.

- “Pridurochni”?

- Well, in slang, those are the ones who didn't work in production but in the residential zone, in the mess hall, as orderlies. And there were those who rummaged through the trash bins. The picture of social stratification was the same as on the outside.

- Did you make any friends in the camp?

- Besides the Kazakh I mentioned, there was a guy from Minsk. He was arrested because he and his friends were planning to blow up a jammer tower. But there was an informer among them, who urged them to do it as quickly as possible. And he had already turned the whole group over to the KGB.

- How did your sentence affect your future life?

- I no longer had the right to be a teacher, a historian. I graduated from a patent institute by correspondence. I worked as a patent specialist. My head of personnel was summoned to the district party committee and told: “No career growth.”

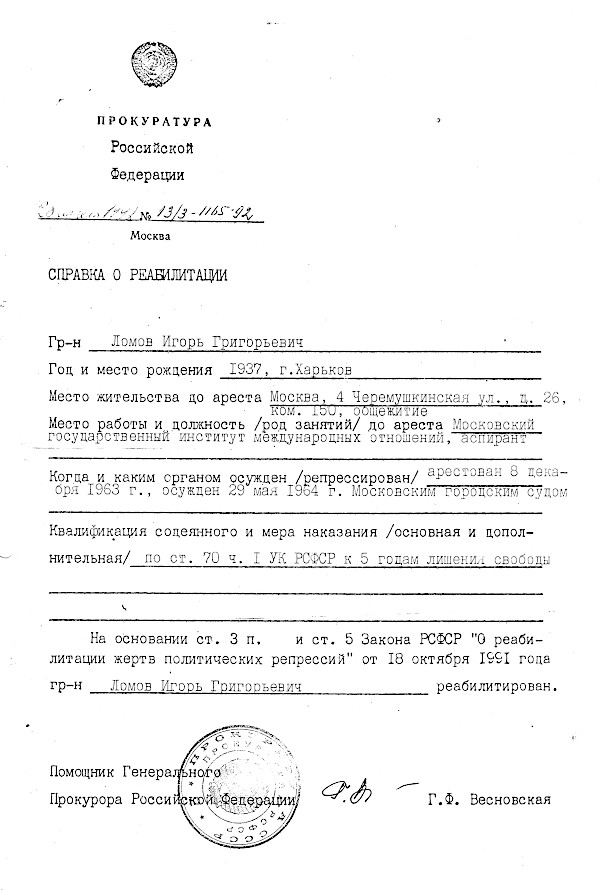

Ihor Hryhorovych Lomov was rehabilitated on April 28, 1992. In the late 1980s, he participated in organizing the Kharkiv branches of the “Memorial” society and the All-Ukrainian Society of Political Prisoners and Repressed Persons. From 1991, he was a member of the Commission for the Restoration of the Rights of the Rehabilitated under the Kharkiv City Council.

05/19/2019