One of the last prisoners of conscience in the USSR, convicted of “stealing” books from the synagogue in Podil, author of short stories who became known under the pseudonym Abrasha Lukyanovsky, Rabbi Natan (Noson) Vershubsky spoke at the invitation of the Chief Rabbi of Kyiv and Ukraine, Yaakov Dov Bleich, at the scene of the “crime”—the Main Synagogue of Kyiv. On observing Shabbat at a Soviet university, informants in yarmulkes and KGB officers, his arrest and investigation, the setup by his lawyer—Viktor Medvedchuk—and Margaret Thatcher's intervention in the prisoner's fate—in an exclusive interview for “Hadashot.”

— Rav Noson, how did a boy from a Moscow intellectual family (father—a journalist, mother—an engineer) become a “religious obscurantist”?

— My secular friends usually say of people like me: “He got into religion,” for some reason thinking that people come to faith only when looking for a way out of a difficult life situation. But I had a happy childhood—I simply wanted to correct a historical injustice, to restore the connection that had been broken by my fathers and grandfathers.

— And the “grandfathers”—in the broad sense of the word—did not appreciate your aspirations?

— There was a war in my family over it. Back in the day, my father went to the front as a volunteer, deceiving the military enlistment office by adding the four months he needed to turn 16. He ended up on the front lines and made it to Berlin, where—already 18 years old—he was drafted for compulsory military service. My grandmother wrote to Voroshilov—it didn't help, and he served another three years in Germany.

When he returned—his chest covered in medals—he could have enrolled anywhere; veterans were accepted without exams. He chose the philology department, dreaming of becoming a journalist—and he did indeed become one. But then he forbade us—his children—from pursuing a path in the humanities. I, however, always loved mathematics, studied at a physics and mathematics high school affiliated with Moscow State University, won physics and math olympiads, and was accepted into the Moscow Institute of Transport Engineers (MIIT).

We argued through the night. My father was an agnostic and a staunch communist, but he could do nothing about my conviction and was partly to blame for it himself—from a very young age, he taught me to be independent. I started taking public transport at a very early age, and my dad taught me everything—from rules for surviving winter in the forest to choosing friends. And now he couldn't win an argument with me when I chose this path myself.

|

|

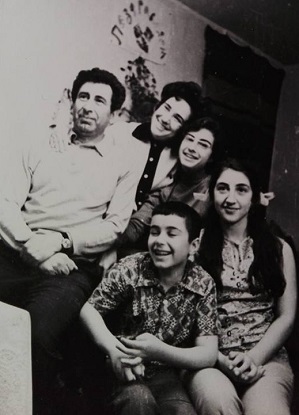

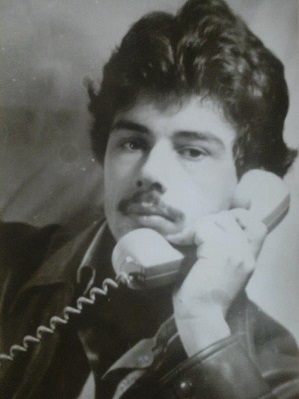

| With his family, early 1970s | At age 16 |

— Internal resistance is one thing—the synagogue on holidays, samizdat at night, and learning Hebrew from a self-study guide—but practical observance of the commandments is another. How did that align with studying at a Soviet university?

— It wasn't easy. Since I had to get a medical certificate from the MIIT clinic before every Sabbath, I developed my own method of faking a hypertensive crisis. Simple auto-suggestion.

— And always on Saturdays?

— Of course, I tried to vary it—sometimes I'd go in on a Thursday. That saved me when, in the early 1980s, the threat of expulsion from the institute loomed, and I made a preemptive move by taking a medical leave of absence.

— But what did they want to expel you for?

— For the sum of my transgressions. First, it was known that I went to the synagogue. Second, I was actively recruiting an audience for a friend, Ilyusha Kogan, who was preparing excellent lectures on Judaism for beginners. I brought him dozens of people—they would stand in the hallway, there weren't enough chairs, and they knew about that too.

There was another sin. I discovered a treasure trove of Jewish literature in the Moscow Historical Library, which only admitted historians and students from relevant departments. And thanks to a petition from the Social Sciences department, I became a regular there—for a bit of espionage, I would take half a dozen books, only one of which was on a Jewish theme. Then, through the same department, I gained access to the restricted-access collection, where they had the Jewish Encyclopedia, Graetz’s “History of the Jews,” and many pre-revolutionary publications. I didn't leave that place for six months, until the rector’s office received a letter from the library director with a list of all the Jewish books I had ordered—specifically the Jewish ones, not the ones I took as a decoy. It was a scandal. People were expelled for much less.

— How did your fellow students and professors react?

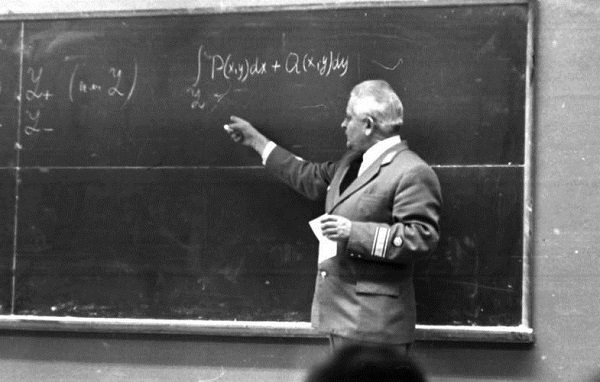

— Some were a pleasant surprise. I remember I had an upcoming exam in higher mathematics, which everyone feared like the plague. The professor was Grigory Ivanovich Makarenko—a Ukrainian from near Poltava, nicknamed “Beyond All Expectations.” I enter the classroom, and Makarenko looks up: “Lock the door, bud laska…. ” And he continues: “Pro-rector Nosarev summoned me yesterday. Are you acquainted with him? I see that you are… Well, he ordered me to give you a failing grade. I'm a decent man—I won't do that. Give me your grade book; I’m giving you a B. Call the next one in, bud laska…”

I knew Nosarev, the KGB man, perfectly well; he'd had it in for me ever since that Chekist, nicknamed Müller, saw me with a Star of David around my neck. But Makarenko turned out to be a one-in-a-million kind of person.

Professor Grigory Makarenko

I was also mistaken about our Komsomol organizer, Senya, whom I gave a wide berth. In a critical situation when they wanted to kick me out of the institute, this guy, with a classic Jewish appearance and surname, stood up and declared that the Komsomol organization knew Vershubsky only in a positive light and would not petition for his expulsion. I found this out many years later and was amazed…

— You are a native Muscovite, but you were jailed for “stealing books” from the synagogue in Podil. What brought you to Kyiv in February 1985?

— To begin with, both my grandfather, a shoemaker, and my grandmother were from Kyiv; they moved to Moscow in 1925. And I used to visit Ukraine quite often for Jewish matters. We in Moscow were lucky back then—we had people to learn from. First, there were still old-timers, and second, foreigners would come every two weeks. A whole system was set up—people from London or Manchester, New York or Baltimore would give lessons on Judaism, bring books, tefillin, and even kosher cheese. They rarely traveled beyond Moscow, so my friends and I felt we had to share this knowledge. Especially since, as a MIIT student, I was entitled to free travel. Some went to the Baltic states, others to St. Petersburg, but I chose the Ukrainian direction.

And I found my bride in Kyiv as well. A year after our wedding, Marina was nine months pregnant—and we decided to visit her parents, who lived in Syrets—it was our last chance before the birth. Besides, my wife's parents were also starting to observe, and they needed our help. So I used the comp days I'd earned working at a vegetable warehouse, and we came.

The first order of business was to perform a chuppah for my father-in-law and mother-in-law, who had been married for 25 years. For that, you need a minyan, and where could you gather ten observant Jews in Kyiv? The old folks wouldn't go to an underground chuppah—they were afraid. So, I had to go around to all the Zionists, refuseniks, and Hebrew teachers—that's what I was busy with.

— And where did they get you?

— Right at the synagogue gate. As soon as I walked out, two young men standing by a white Volga with KGB license plates grabbed me by the arms and took me to 33 Vladimirskaya Street. And then they spent the whole day trying to figure out what to pin on me. There were various ideas. They threatened to search my Moscow apartment and find anti-Soviet literature. I honestly admitted that I had long ago removed all anti-Soviet literature from my home. “We'll find some,” was the reply.

KGB building of the Ukrainian SSR at 33 Vladimirskaya Street

A series of arrests was underway at the time—every month, they would take one of the religious Jews. One—this was in Samarkand—was jailed for allegedly hitting the chairman of the religious community over the head with a teapot. In reality, he was teaching tradition to children—that, indeed, was serious. During a search of another's home, they found a Walther pistol and ammunition for it—they found it immediately, apparently they knew where to look, unlike the owner, who was seeing the pistol for the first time in his life. At a third one’s—the current Speaker of the Knesset, Yuli Edelstein—they came with a search warrant and, upon finding spices for Havdalah, arrested him for possession of narcotics. An elderly Jewish man from Kyiv was arrested for beating up six policemen in some provincial town—if I'm not mistaken, Novohrad-Volynskyi—where he had gone to visit his father-in-law's grave. So what did I have to complain about?

— Did you understand that it could end this way? Were you prepared to go to prison?

— Absolutely not. My father warned me: “They'll put you away,” but I didn't believe him. I believed in two myths that shattered the moment I was arrested. The first myth was that they only jail the big fish, so to speak, and I was small fry—I didn't meet with foreign correspondents, didn't give press conferences, didn't sign petitions, just studied and taught the Torah. The second myth was that they intimidate people before they take them in—call them into the KGB, warn them about the consequences, etc. That happened sometimes, but not in my case.

— As I understand it, someone had to give false testimony against you, and they did…

— Exactly. Nowadays, when you enter the synagogue, you see marble plaques with the names of sponsors, but back then, there was one large inscription that stood out—OUR CHAIRMAN. The chairman in those years was Meishe Pikman. Back in Moscow, Lipa Meshorer—a former Kyiv resident himself, knowing I traveled to Kyiv—warned me: “Meishe has been an informant since before the war; he's got blood on his hands up to his elbows.”

However, I didn't interact with Pikman; I spoke with his deputy—Milman. And when the KGB decided to try me for stealing books from the synagogue, they simply brought these two gentlemen in and dictated the text of their statement in the next room with the doors open—I heard it. They wrote everything they were told: that I had asked if I could take books, they had said no, but I took them anyway. You have to understand that back then, in all the synagogues in the Soviet Union, the attics and basements were piled with old Jewish books, brought by the children and grandchildren of observant Jews—they were no longer needed at home, nobody remembered those letters anymore. In the Podil synagogue, they were just lying on benches, on the floor, on windowsills—rats were eating them and pigeons were pooping on them. Milman himself had asked me to take whatever I needed.

Synagogue in Podil. In the center is the community chairman, Pikman; on the right, his deputy, Milman.

But if they need to put you away, incense becomes narcotics, a Walther is found under a bookcase, and a Jewish pensioner, like Schwarzenegger, beats up six policemen. In my case, four books found in my bag turned out to be stolen from the Kyiv synagogue.

In court (I was already shaven, but before my arrest I had a beard), I ask Pikman: “Do you remember me? Was it me who approached you?”

— Yes!

— And was I with a beard or without?

— It's just as it is written in the report.

— But please, answer my question.

— I refuse to answer!

And the judge grants his refusal to answer. But we didn't even know each other; I had only spoken with Milman, who didn't show up in court due to illness...

— Have you forgiven these people?

— I don't even know if it's appropriate to talk about forgiveness… It was pitiful to look at these unfortunate old men—I didn't consider them enemies. They were just instruments; if it hadn't been for them, I would have been imprisoned anyway.

I was in that courthouse today—now it's the Podil District Court on Khoriva Street. Back then, after the trial, some *urka* cellmate, who knew more Yiddish words than I did, told me that Beilis was tried in this very courtroom… Although Wikipedia doesn't confirm this.

— Your lawyer in this case was a man now very famous in Ukraine—Viktor Medvedchuk. What kind of impression did he make?

— My relatives, of course, were looking for a lawyer. But everyone they approached, upon learning the case was under KGB control, flatly refused to defend me. My wife's grandmother—a former member of the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR—still had connections in those circles, but they turned her down too. My father found a good, brave lawyer in Moscow who was ready to take my case, but he honestly warned that he simply wouldn't be allowed to reach Kyiv—to the point where the train might even derail.

Until someone suggested that there was a lawyer in Kyiv—a KGB captain himself—who takes on such cases. As a result, they turned to Medvedchuk. He couldn't influence anything, of course, and he was a lousy lawyer besides. I myself, sitting in my cell, pored over the Criminal Code of the USSR—and I earned my keep that way—drafting petitions for *zeks*, complaints to the supervising prosecutor, requests for case reviews, etc., in exchange for a daily ration of sugar. In the same way, I prepared the questions for the experts in my own case, who appraised the “stolen” books at 700 rubles, although they couldn't even read what was written in them.

Khoriva Street, 1980s. Photo: starkiev.com

Medvedchuk didn't ask the experts a single question. However, every time he came to see me at Lukyanivska Prison, he would bring a kosher chocolate bar in his shirt pocket, a small package of kosher cheese, and a letter from my wife—though he wasn't obligated to do this; letters were forbidden in the pre-trial detention center. We didn't discuss anything during these meetings—he would wait for me to eat the chocolate bar so he could take the wrapper, and for me to write a letter back to my wife.

He did, however, commit one dirty trick. Despite all his persuasion, I refused to admit guilt. But he insisted—if you plead guilty, I'll file for a pardon. Later in court, while I was sitting in a defendant's cage in the basement during a recess, Medvedchuk told me that my father thought I should plead guilty. I had no contact with my father; he had barely managed to get into the courtroom. When the hall opened at 9 a.m., all the seats were already completely filled with law students. An open trial that, in reality, no one was allowed into. My dad showed his passport—my son is on trial. So they recalled one student, and my father took his place.

That day, Medvedchuk relayed my father's supposed request. So when the session resumed, I declared a partial admission of guilt. After my release, when my father heard this story, his eyes widened: “I never even spoke to your Medvedchuk. And I would never have told you what to admit and what not to.” I never forgave my lawyer for that dirty trick. Otherwise, he was just a postman, bringing me chocolate bars and letters from my wife—during the investigation, I ate two chocolate bars and two slices of cheese.

— At first, the prosecutor demanded eight years in prison, which is quite an overreach for the theft of four books, even very valuable ones. And then suddenly, at the next session, he asked for only two years with the same conviction. What happened?

— From the very beginning, the KGB tried to recruit me. When they first brought me to Vladimirskaya Street, they offered to let me go without even a report in exchange for my agreement to snitch. After the case was sent to court, they promised two years (and release after one year) for signing a cooperation agreement. If you refuse—you get your eight years and come out disabled… And my son had been born while I was under investigation. Nevertheless, I refused.

Everything is in the hands of the Almighty. Two years later, the people who had offered me a deal to inform were no longer alive; they—two agents and their boss—died in the sinking of the steamship “Admiral Nakhimov.” And five years after that, the country whose security they had so zealously defended from me was gone too.

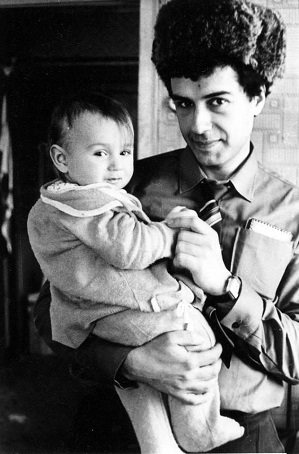

|

|

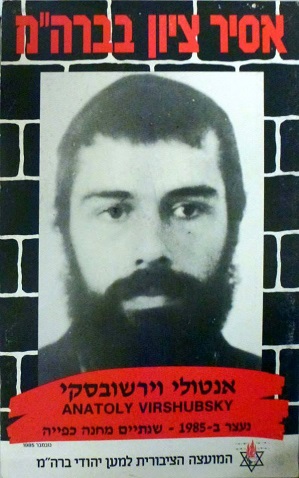

| Holding his firstborn | A poster demanding the release of the Prisoner of Zion Vershubsky, mid-1980s |

There were two ways to fight for the release of political prisoners. The loud way: demonstrations, petitions, pickets, appeals—I asked them to do without all that. And there was the path of quiet diplomacy. That's what worked, though the chain of events was quite long. A certain American Jewish businessman, flying through Moscow on a transit flight, learned about my case from friends. He called his rabbi in Baltimore, who pulled some strings with someone else—as a result, the rabbi of Manchester met with the Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, Lord Jakobovits, who, at a reception with the Queen, gave Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher a list of eight religious Jews recently arrested in the USSR. I was number seven on the list.

Some time later, Thatcher handed this list to Gorbachev at a meeting. No one was released, but the fate of all was significantly eased. Many years later, looking through my case file, I found a letter from the Prosecutor General of the USSR, Rekunkov, to Kyiv with instructions to demand a sentence of two years, not eight, in the Vershubsky case. Accordingly, the next morning, the prosecutor announced the new order, and in political trials, the judge would grant the prosecutor's request exactly. How were criminals tried? If the article of the code specified a sentence from one to three years, and it was a first offense—they would give two years. That didn't work with political prisoners. Neither my references (and surprisingly, I had a good reference from my workplace) nor my newborn son had any influence, although Medvedchuk tried to emphasize these points.

— What was it like in prison?

— I was a sweet, naive boy from an intellectual family, and then suddenly—bam. *Urkas*, *blatnye*—after all, the charge was criminal. Case files were marked back then—a red stripe in one direction meant “prone to escape” (a so-called *sklonnik*), a stripe in the other direction meant the case was under KGB control. They tried not to keep such people in the same cell; they were constantly transferred. The operations unit feared their corrupting influence on other *zeks*. Therefore, although by the rules I should have been with first-timers, in the pre-trial prison I was cellmates with all sorts—even *vory v zakone* and, for one day, a man on death row.

— Did you manage to preserve your integrity?

— I saw many broken people—it’s hard to understand for those who haven't been in prison. And I came to the conclusion that those two years in prison helped me not to break after my release. A seditious thought sometimes crosses my mind—if those KGB men had sent me in 1985 not to Lukyanivska Prison but to an Israeli yeshiva to study the Talmud, it wouldn't have been such a good school. The prison experience tempered me powerfully. In my book, I write about two things that allowed me not to break. First, letters from the outside world. People who received many letters broke less often. The same goes for religious people. Those who were connected with their people and connected with Him. When a person feels that he is here for a reason, that the Almighty is guiding him. In the most difficult moments, I thought that I was here by the will of the Almighty, and He knew how much I could endure. And so it turned out to be…

Interview by Mikhail Gold