Ovsienko V.V. .: 10 July 1999. We are having a conversation with Mr. Valeriy Kravchenko. Ovsienko V.V. recording. The conversation is taking place outside Sagaydachnogo, 23 in Kiev.

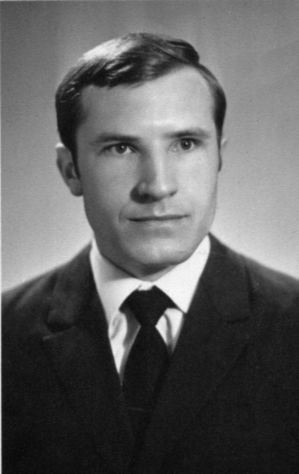

V.O.Kravchenko. : I was born on January 2, 1946. In Uzbekistan, in Tashkent region, in a small town of Behovat. My father served in the militia, retired senior lieutenant. He was an authorized operational, meaning he was a criminal investigator. My mother was a nurse. I graduated from high school No. 13 in the town of Chyrchyk of Tashkent region. Me father had constant transfers in his career, he worked in Tashkent and around Tashkent region. In the end, he finished his service in Chyrchyk and thats where I finished middle school, though I started studying in Tashkent school.

After high school, I tried to enter the Tashkent Polytechnic Institute, but failed. From there, from Tashkent, I was then recruited for military service. I served in Lviv region at frontier No. 9 named after Hero of the Soviet Lieutenant Lopatin of Lviv frontier.

I was a devoted member of the Komsomol, praised communist views and was convinced of their righteousness. I was part of the Komsomol back at school and then in the end, after military service, I worked at the Arsenal factory in Kiev as a turner after joining the Communist Party. I was a member of the Komsomol committee at school, then a member of the Komsomol bureau at the frontier, a secretary of the Komsomol organization at the frontier. I was also a member of the Sokal regional Komsomol committee. After military service I became a member of the Komsomol guild committee at the Arsenal, deputy secretary of the Komsomol organization department. In 1970 I applied for a membership in the Communist Party of the Soviet and joined it in 1971.

Ovsienko V.V.: Please tell of more of your parents. .

Kravchenko V.O.: Father - Kravchenko Olexiy Kuzmych, born in 1909. He is no longer alive. My mothers maiden name was Panchenko Anna Kononivna. From dispossessed. My fathers parents fled from dispossession, and my mothers parents did not have time to do the same. They lived in Siberia, Omsk region, and they were exiled to the Siberian swamps. And my father and mother were born in Western Siberia, father - in Kustanai region, mother - in Omsk region. My mother wasnt in exiled because she was still underaged, but her whole family got deported back then. My mother entered the labor faculty but was told upon by one of her friends and being daughter of a kulak family she was kicked out. After that she graduated from nursing courses and worked as a nurse for a living. Both my parents died in Chyrchyk - mother died in December 1998 and father died in December 1990.

Ovsienko V.V.: And how did their parents end up in Siberia?

Kravchenko V.O.: My father told little of hid parents, he had no interest of their lived...

Ovsienko V.V.: His family is from Ukraine, right?

Kravchenko V.O. .: Yes. I think my fathers grandparents were from here. My mothers parents were from Cherkasy region but they had left, because when the Stolypin reform took place, the authorities were giving out land in Siberia on preferential terms. They already had one child then, my aunt – Yaryna. They went to Siberia around 1908. Their family was among the richest in the village until 1927, so they were the first to be dispossessed when the time had come. Granddad had a mower, horses, oxen, many sheep and a grinding machine so after harvesting all those who had something to pay with came to him grandfather to use the grinding machine. They were lucky They were actually lucky to be first for dispossession because those who were first were then given something to take with them, they travelled to exile on their own oxen and cart, and with their herds. Those who faced dispossession later were left with nothing at all. Thats the background story...

Ill return to my life now. That two-faced nature of society ... Though I was convinced of the correctness of Marxism-Leninism, but those kitchen debates, the talks mother and father had, words that people spoke – that was one thing, whereas officialdom – was something far different. I remember I had no questions about what was what. Why had I no protest at first – because I saw the difference between that officialdom and reality? This life view was something which was in me from birth: I saw people living their tough lives, being in need and having to do hard work on one hand and radio with newspapers writing something totally different on the the other hand. In result, people quarrel between themselves talking bad things about life but in public they still praise the party and the government. They grow up and live in that lie. Having seen all that, I held those lies as if they were normal. The dilemma is in the fact ideas of communism are great, and they are easy to believe in – they praise equality, fraternity, absence of exploitation of man by other people. I believed in bright future of mankind. But then I grew up and saw everything as it was, started feeling all the injustice of labor distribution. I saw that one does nothing, the other works hard but theyre still seen equal and theres no escape from that equality, and I felt all the injustice of equality on myself. For example, we had freedom and brotherhood on one hand, but if one tried to say anything against the authorities - they immediately implemented measures of administration. Lets not take me personally, but I felt that I was in the same condition and if I just tried to stand against – I wouldve found myself in the same situation. But then again – I grew up in these circumstances – I felt that was the way it should be. However, protest began slowly rising inside me..

My failures to enter university definitely effected this. I applied to Shevchenko University for the distant learning department of the Philosophy Faculty – wanted to be a Komsomol party worker, and therefore wanted to join that department. In the end I passed all the entering exams. The first attempts after the army were quite unsuccessful though – I had low marks, and the first time I even failed the exams. But then I prepared well and passed and passed the exams with high marks. My literature works had the highest marks, though they were so demanding that not every writer would have passed. But in the end all my efforts were in vain. And it certainly affected my attitude and my ideological reorientation. I clearly saw the difference between officialdom and reality.

But one can not call my failures the only reason. There was this situation once. I still remember it. There was a newspaper Trud No. 27 dated 1971. A worker of our factory, currently deceased, Rezvinov Mykhailo Yiakovych spoke out with his article Time to stop corruption. This article caused very decisive action of the administration towards that man. However, a commission even came from Moscow. Rezvinov proved that everything stated in this article, all the flaws – were true. But as soon as the revision group left, he was immediately cut wages (he was close to retirement age). The organization of labor was such back then, that if you had been working well and did not cause anger of the administration, they gave you a bit more money, so you had, you know, more or less adequate pension. And Rezvinov faced the opposite side rather than increasing his pension they cut his wages – he began earning 70 UAH or 90 UAH.

Ovsienko V.V.: No. RUR were still around back then.

Kravchenko V.O. .: Yes. This hit him badly. And I, for once, saw what was this labor freedom of the workers – workers who criticize get lower payments. Neither the trade unions nor the Communist Party organization and Komsomol – no one was going to help him in his trouble. So where was the labor solidarity then? This influenced me a lot. I said that the article was in the 27th issue of the newspaper Trud (around February) dated 1971.

That same year I made another attempt to enter university, I passed the exam but I was still denied into the university. I looked around and thought: why do I have to lie to myself and why should I bend to the system? I must protest, we must confront this system, we have to show this system an example. I wrote to the Brezhnev in Moscow to condemn the internal politics of the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Do you remember the date of writing this letter?

Kravchenko V.O. .: I dont remember. Somewhere in the end of 1971.

Ovsienko V.V. .: And what did you write there? Was it a big letter or a small one?

Kravchenko V.O. .: It was a lengthy letter. I wrote that I believed in communist ideas, and I continued to believe that they were correct, but the implementation of these ideas, the policy pursued by the Communist Party, is not perfect, that human rights in the Soviet were not respected, thus Khrushchevs policy deficiencies could only be corrected by Khrushcheva dismissal from his current position. And your mistakes, comrade Brezhnev (or Leonid Ilyich - I do not remember what exactly I wrote), are also obvious, and they will be eventually seen negative by our descendants. Finally, I stated that I was leaving the Party as part of my protest against this policy.

It was, so to say, my first step towards dissident-ship. The letter, of course, was returned to Kyiv. Initially my personal case went through a hearing in the guild party bureau. I was dodging around, understanding who I was talking to in the guild bureau I did not have anyone to support me or to sympathize for me there. Therefore I chose one way of behavior in the bureau. And at the bureau gatherings – where there were many workers – there I stood up and said everything as I felt it. I was standing on my own, I spoke about the flaws at the factory which I saw. I kept being interrupted. But my resolute behavior helped me look positive. I remember this was at the Shapiros factory manufactory, he took his word, started saying something against me, but, you know, as they say among the people, he was just mumbling, eyes to the floor. I interrupted him and said: What are you talking about? What are you looking for down there among the chairs? You look me in the eyes. People in the room even laughed.

Ovsienko V.V. .: That meeting had only members of the party organization or, perhaps, other representatives?

Kravchenko V.O. .: Bureau deputy Dovbilov was present.

Ovsienko V.V. .: And from the KGB?

Kravchenko V.O. .: I think not. I have not seen such faces, although I wasnt looking for them back then. But it is quite possible for Arsenal was a military factory, and Deputy Director of the regime and personnel – was the militia, and OBKhSS and KGB – all in one. Thus, it is possible that some of the factory workers were performing these functions.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Its a must. I want to ask whether you had been influenced by, for example, such extraneous factors as radio Freedom, Voice of America? Or did you come to the mentioned conclusions all by yourself?

Kravchenko V.O. .: I sometimes, of course, I listening to Voice of America. I lived in a hostel with my roommate, he listened to the Voice of America, but it wasnt that ever paid too much attention. Although, of course, the examples of Sakharov, Solzhenitsyn were there for me, I knew everything about them, but Solzhenitsyn described the Stalinist repressions, which had already been criticized, and it wasnt news or a taboo subject for me. After a few years, when Solzhenitsyn was deported, I spoke out with a protest, and even spent a few days on huger strike out of protest against the persecution of Sakharov and Solzhenitsyns expulsion.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Did you make any statements?

Kravchenko V.O. .: Yes.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Where did you apply?

Kravchenko V.O. .: I sent a letter, but I dont remember where.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Since your first letter to Brezhnev was sent in 1971, these meetings had already taken place when the arrests of Ukrainian intelligentsia took place in early 1972, right? Did you know about this Ukrainian movement or were you away from it?

Kravchenko V.O. .: In early 1972 I knew nothing about the Ukrainian resistance movement.

Ovsienko V.V. .: You were out of this movement, right?

Kravchenko V.O. .: Away from it completely.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Allow me to ask this: were you a Russian speaker at the time or you apoke Ukrainian?

Kravchenko V.O. .: I spoke in Russian. I understood Ukrainian, read books in Ukrainian, though. I also know a bit of Uzbek – I know how to say hello, how to say goodbye, to apologize, I know that Arba is a cart and God is the road, this is probably everything I know. I did not know Ukrainian language, but felt myself Ukrainian. My father had been accidentally recorded as Russian in his passport, and my mother was recorded as Ukrainian. Despite this, I recorded myself as Ukrainian in my passport, because that was what I felt. I remember, being a child, during these Christmas Carnivals in school - they were not like now - I prepared a Ukrainian national costume. I remember that I had a very strong impression after studying Taras Bulba. I remember Ostaps drawing before execution. I sympathized a lot to Ostaps character and was proud that he was Ukrainian, and moreover – I wanted to be Ukrainian, as Ostap. In addition, even though I lived in Uzbekistan, our Ukrainian songs like Marichka, say winding like a snake is the restless river ... made me fall in love with Marichka and the image of the song.I was very fond Tarapunka and Shtepsel, knew their dialogues by heart, knew all Ukrainian words Tarapunka used.

Ovsienko V.V. .: You mentioned protesting against the deportation of Solzhenitsyn, Sakharovs letters in defense – we stopped at that point. Please continue ...

Kravchenko V.O. .: So, I spoke in their defense. But that was then. When I wrote a letter to Brezhnev, manufactory gathering decided to expel me from the party. After the meeting I was invited to the party committee of the factory, where they also looked through my case and had to be approved at the guild meeting. That was according to the requirements of the statute. And I must say that there had been softer and more objective decisions, they used phrases like consider retired. This is different to “expelled”, although, as much as I know the Statute of that time, this case was out of the Statute. According to the Statute, there was no such formulation as retired, you could only be expelled from the party. But the record said retired (I think that was the error of the party). After a conversation with the factory committee, I was invited to have a conversation at the town Party Committee, where I talked to Kalyakina (instructor of the Municipal Party Committee). She urged me to reconsider my view. We had a very long conversation. She told me that I would spoil my life if I left the Party, Im a good guy she said, I should try myself again to get into university, she said. She hinted to me: “Call me when you go for our exams. To this I asked asked: If I submit an appeal and stay in the party - then call you? - No - he said - if you will try and enter university, message me. Thus, she hinted that she will help me. But I was well aware that she wouldnt have helped me if I didnt stay in the Party. And if I do not stay, joining university will have no value because there will be no joining. And who would have accepted me anyway? I am well aware of all this. I refused to appeal, and it all ended, I left the Party.

Ovsienko V.V. .: So you got expelled, right?

Kravchenko V.O. .: Yes.

Ovsienko V.V.: And formualtion? ..

Kravchenko V.O. .: Consider retired.

Ovsienko V.V. .: And at the meeting they formulated your leave as?

Kravchenko V.O. .: Expelled.

Ovsienko V.V. .: For? ..

Kravchenko V.O. .: For violation of the Statute ... I do not really remember that formulation, the only thing I remember clearly is that they “expelled me.

Ovsienko V.V. .: For ideological faults and errors ...

Kravchenko V.O. .: I can not say because I do not remember - it was too long ago, and I especially did not attach importance to.

After I left all the holiday leaves became at my own expense, even if necessary - holidays in the summer months were now forbidden for me. I didnt have any vacations in summer. Thus, all means that were in the arsenal of the authorities had been applied to me. This led to protests on my part which caused new measures applied by the administration. All this went on for a long time.

I got married in 1975, when I was almost 30 years old. I got married in November and in May 1976 we had our first child. Once married, I left the hostel and moved to an apartment. It had terrible conditions. You should understand that finding an apartment for a family with a child was difficult. There was a serious lack of sanitation. My wife got ill because of lack of sanitation, including female illnesses, our child once had worms. Having worked at the factory for many years, I asked to get me at least some temporary apartment for living. But who was going to give me that home? Factory administration felt that I was in a difficult situation, and they I never failed to remind me that I did something that was unacceptable to them.

Having found myself in such a situation, my soul only gained further protest. This made me even more determined and woke up my inherited adventurism. I wrote a letter to Brezhnev, which described the measures applied against me and that they infringed my human rights. In that letter I stated everything as it was although I was aware that letters never got to him. So I decided to do something else.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Im sorry, when was this letter sent?

Kravchenko V.O. .: Im not sure I could even name the year correctly, but I think it was around 1977. It can be calculated as that was the year when Cyrus Vance, the Secretary of the United States, arrived in the Soviet and had conversations with Brezhnev concerning SALT. I wrote this letter, but knowing that letters dont reach Brezhnev I decided to contact the American embassy and went to Moscow. I was not sure whether this would have worked. I did not know whether the American ambassador could pass on my letter to Brezhnev, but I decided that it could be possible. So I decided to give my letter to the US Ambassador Michael Tun. So I wrote the letter to Brezhnev, sealed it in one envelope with his address, but placed it inside another envelope with a letter to Michael Tun. I wrote to the ambassador asking to pass it on to Brezhnev and stated everything written in that letter to Brezhnev. I wrote that I ask to pass on this message personally, unless it is forbidden by the international standards.

I came to Moscow. I did not know where the embassy was. I didnt check the address at the address bureau because I knew that if I had I would have never got to the embassy. If I asked passers-by the consequences were likely to be the same. So the question was, how to find out the embassy location. I came up with one option: arriving at the Kyivskiy station, I walked a bit around Moscow, looked a little further from the station, remembered the name of one street and returned to the station. Took a taxi and told the taxi driver that I had a bit of time and I was about to go to the movies, and that I knew the US embassy was on the street I remembered. I said I knew there was an embassy there and that I wanted to take a look, at it. Which embassy is on that street?” - the taxi driver knew for sure where the embassy was located so he told me the street. Well, lucky me then, please take me there so I can take a look.

He drove me to the embassy, and then after we started off from there, I asked him to stop at the first cinema we saw because I wanted to go to this cinema for a movie. I paid the taxi driver and left, knowing where the embassy was.

I began looking for opportunities to pass my message. Our militiamen were standing before the entrance of course – so entering like that was out of question. There were cars at the entrance and all of them had number plates starting with D and the first number was 25. I understood that those were the American series. I walked away from the embassy and waited at the crossing for a car with “D 25” number plates to stop at the red lights. I waited for a long time and then an opportunity came: I approached the car, opened the door and said: Sorry, please, you speak Russian?, there was a woman there all scared: No, no! I closed the door quietly stepped back to the sidewalk, stood a bit longer and walked away as if nothing had happened because I realized that this was my first attempt, and that there many “our people” in front of the embassy dressed in civilian clothes. I walked away from there. Trying to pass the message with people in cars at the crossing did not give any results.

There was a house near the embassy, where Shaliapin lived. I stood away from the embassy, as if I was overlooking Shaliapins bas-relief, but I was watching out if someone would be leaving the embassy and approaching cars with D 25 number plates, and if that person looked American I would talk to him and hand the letter to Michael Tun.

I spent a lot of time there and, as I thought, became familiar. I decided it was time to leave that place, but then saw a man who looked like someone I could address if he approached the needed car. The man turned and started walking my direction. He passed me, and my intuition, together with his appearance, suggested: he was not local! I let him pass and thought that he was the guy I should follow.

I went after him, checked for tails, but didnt see anything suspicious. I caught up on the man and said: Sorry, please, you speak Russian? - Yes, I do. - And you are an employee of the American embassy? - No, Im not, Im the Consul General of the USA in Leningrad. Even better – I thought! I told him who I was, told my idea and asked him if he could pass on my message. I said that I didnt care if someone saw that I was passing the letter to him now and then I would gt arrested – it didnt bother me. “But will you take this letter?” - “And where is this letter? I bought a little child book and inserted the letter into the book not to keep in my hand. I told him of where it was and he offered me to give him the letter together with the book. There you go then. I gave him my letter.

The fate of that letter is something I dont know. I could not find out anything back then. The only thing I knew was the upcoming arrival of Cyrus Vance. This visit was to take place in just a week.

Back at the factory I met the head of production, dressed in working clothes as it was the first working day of the week, and told him that I was in Moscow and in the United States ambassador handed a letter to Leonid Brezhnev and I said that informed him of the fact that there was to be a meeting because of my letter to Brezhnev and that he shouldnt be surprised, because I wished no harm to the Soviet diplomacy in negotiations on limiting strategic offensive arms. This of course caused a storm at the factory.

Ovsienko V.V. .: So you told this news to other people, not only the director?

Kravchenko V.O. .: You see, the thing is that as soon as I said it to him, he led me to his office and summoned all his deputies. It was like this: he sat at his desk, I stood before him at the side of the table perpendicular to his desk, and all the deputies sat at the wall. And well, the plant manager was literally enraged. He was officially a Hero of Socialist Labour, deputy of Verkhovna Rada Sergei Gusovskiy. The street near the Arsenal bears his name if I remember correct where supermarket Pecherskiy is situated. So he growled: How is this possible? At our revolutionary factory, such a man, here such a good team.... I answered him: Oh! So you even remembered the good team! And then, completely without fear, because I was ready, I said:You must have forgotten about recent deaths! Has it been long after it happened?

There was an accident recently at the factory: steam was pressuring out of the tubes eroding the pavement, and people walking past that place to the cafeteria, fell in that hole and got terrible burns, two died. So you forgot about the good team back then, but now you think about the team and now you remember about the revolutionary factory? The deputies sat so quietly that we could hear the flies in the room! The head of the factory was growling at me and I growled back. He saw that he couldnt do anything and said: Go! Get to work!

I went away and all the rest remained. Measures against me had then become even tougher after that situation... I was working in the tool department and the specificity was that the production was all artificial, every detail had to be made only once or twice. The technologists, however, wrote the technology anyhow, they were not very professional and mostly consulted with workers because the workers were universal. This is very different from a production batch when a person makes the same items in large quantities.

Every detail requires the workers to think the technology through thoroughly.

With artificial production there was always this way of stimulating labor called recoil. The person had his price – almost the size of his salary, but the salary was flexible: if the head saw that a worker was cunning or doing bad work, he could have had his salary cut down by 10 or twenty RUR. All the work had its planning, but the worker could change certain prices. So the head could actually manipulate the amount of money his workers got. This made it possible for Rezvinov, of whom I told, to cut salaries. Thats what was used against me.

According to the principle of recoil I was getting around 200-220 Soviet rubles, and in the first month after the event I was cut down to 100 rubles. The next month, because I had to hurry and I tried working more, I ruined some expensive parts and my earnings were none at all. Out of protest I simply refused to receive the salary I had earned. After the third month of this persecution I have not been removed from the factory, and again my salary was very small. I had no money to pay the rent, I was in a terrible situation. Factually I had to make a choice whether to live or not to live.

What to do? I had almost lost the will to live when something happened. I put myself together and told myself that I shall stand or die. I started taking jobs for drawings, preparing all the tools that I needed to make the next day. So I upon coming to work, I was psychologically prepared to do the job. Apart from that I really felt this winged statement on myself: A great purpose creates great power. Where did it all come from? I did not understand how could I manage all this. I began earning at the rates of the drawings. Setters, however, intentionally lowered the prices so the workers could not earn more than set by the administration. Workers were getting dutiesaccording to these prices, after that the master brought the job prices to his level – thats why this procedure was actually called recoil. And I was given nothing, so I had to make money on those under-priced orders, for which the workers earned half or one-third less than what their order list said at the end of the month. Its very difficult to understand for a person unfamiliar with the working scheme, but it was true, and it was known by those who had been working according to the recoil scheme.

So as I got down, in three months my salary was so low that I did not earn even half the money I had to, but after the fourth month I earned a little more than I earned at recoil prices. When it happened and I saw that it is possible i got inspired. Therefore, having gained experience of such work in the first month, I earned even more in the next month. My master did not know what to do with me, because he had to make my salary decrease and it was only growing. And he couldnt lower the prices even more because he did not know which projects will I get. And the prices, moreover, were not set by the master, but by the setter. The drawing came prepared, thus, lowering the prices would have been too obvious. He began talking to me a little more frankly: Valera, dont work too fast because the prices might be decreased again. And ironically tapped him on the shoulder and said: Tymofeevych, if they decrease my prices again, I would be interested to see how you pay off to those people you recoil. Dont scare me, just wait a bit and youll see me take away your last! (This meant that after they applied measures to me, they will the same to him). The master had a budget for his people, thus, the overall salary amount all workers had to be no more than a certain amount and if such excess took place, the master could have been reduced his so-called bonus.

Seeing that I dont depend on the administration anymore and that I earn despite all the persecution, I felt even stronger and even started taunting the administration. And that was something the administration could not stand. Why? Because all the workers personally saw where my protest has lead me. To end this they put me on recoil basis again but transferred to a different department, where the work was the hardest and most unwelcome. It was quite humiliating, overlooking the fact that I had the 5th rank but had to work as someone with no profession.

Ovsienko V.V.: You had the 5th rank?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. But at least they stopped lowering my earnings. My new head of department, Razbytskiy, was a nice guy. Every time the administration told him to turn me down, he passed the information on to me.

So anyway, I started working in this dirty low-grade department, but I just accepted reality, kept working and protesting. I remember that during the elections I wrote to my boss that I will not come because those elections were all falsified anyway.

Ovsienko V.V.: What year were those elections? I remember some elections in February or March 1979. I was sentenced recently before them.

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes, those were the elections Im talking about. But they were to Verkhovna Rada of USSR. And soon after that I started thinking that I was not good as a father, because I couldnt provide my family with everything needed. Later I made my next move.

Ovsienko V.V.: When was your child born?

Kravchenko V.O.: 1976. In May.

Ovsienko V.V.: And the name?

Kravchenko V.O.: Oleksiy. So, I made this next move of mine... In March 1979 I committed my first “hooliganism” crime.

Ovsienko V.V.: On the 20th of March 1979.

Kravchenko V.O.: I made a poster and wrote “NO to Breznhev cult! Stop the despotism!” on it. My sentenced, however, only stated that the information on the poster was of “provocative and insulting character”. I came to the department of the Central Committee of the communist Party in Ukraine and intentionally chose such time when there was no one around. My sentence, however, stated that the street “was full of people”, which was a lie.

Why did I choose the time with no people around? Because dissidents were often accused of using there ideas in mass media to be heard by many people. The only person around was a lonely militiaman.

As soon as I unravelled my poster, the militiaman arrested me, lead to his interrogation room and started the interrogation. After some time another man came, a very intelligent man with good manners, and continued my interrogation. As soon as he showed up I understood that he was from the KGB. I explained my actions as the result of offensive actions against me back at the factory. We had a long talk, but surprisingly, they gave me a warning that next time I will be arrested and let me go.

The KGB agent even asked two of his men, dressed in civil clothes, to walk me home because it was late. During the walk I asked them of the reason they were walking together me. They said that it was for my own safety.

It is important to mention here that I was linked to foreign representatives through the Consul of the USA in Kyiv Robert Howard Mills. We met in Hotel “Moscow”.

I should explain myself a bit here. There have been inequalities at the factory, connected to the fact of lowering prices for finished products by the master or the administration. Sometimes the administration had defected drawings and, as a result, defected products. In this case, the product thad to go back for remaking and it happened so that the price for such a product was somehow higher than it used to be. This was wrong and when I had the chance prepared photographic proof of such injustice and passed it over to the Consul.

Ovsienko V.V.: How did you enter the building, did they just let you in?

Kravchenko V.O.: Two times I entered without problem, but after the council was moved to Horkoho street I wasnt let in. However, by that time I knew the telephone number of Kevin Closs, the chief of “Washington Post” in Moscow so I called him when I needed to.

Our secret services knew of my connections with him of course, and that, I guess, was why the KGB agents walked me home that night.

Different people addressed me in different manner. Some of them persecuted me out of personal initiative, others, like Nitchenko, the head executive and a KGB informer – because they had to according to their duties. Nitchenko, for example, didnt feel anything negative against me, and I had no hard feelings against him. After I was released we even greeted each other.

But the most important thing was that they kept me without an apartment. And that made me feel awful. I understood that all I was doing gave no results. I felt that the right thing to do was to start a conspiracy campaign and that was what I tried to do. I even acquired a contact of a guy from the town of Ivanovo, but I felt that he was an infiltrator from the authorities so I decided not to keep up this relationship.

And then my wifes brother, Mykhailo Gudzovskiy, told me of his acquaintance at the construction company. There was a man named Kozliuk Leonid Makarovych, who was writing letters of protest and what was important was his signature under those letters: “Kozliuk Leon, Makarov son”. I became interested and decided to find out more about him.

After some time I went to meet him, aiming to offer him my conspiracy campaign without telling my name details.

We talked and agreed to meet later in another place.

We met for the second time in Hydropark in Kyiv. It was summer but I dont remember the year. I offered him my plan and stressed attention on the fact that he should not know who I was and who other people in the campaign were, and that they shouldnt know who he was either. The idea was to offer them our conspiracy plan without telling them who we were.

I paid attention to the fact that he had one finger less on his hand and in addition to that he was openly protesting, so he want good for a long term cooperation with me for the reason of his visibility, but I had no choice. Later, however, he didnt turn up for a meeting we organized and when I visited his place to check on him I felt that there was someone behind the door but didnt open. I came again after a few days but couldnt get in. After that I had to stop cooperating with him of course.

Returning to the question of being given an apartment – I was still given nothing by that time. I tried solving this issue but all was in vain. The pressure against me was getting stronger so I was forced to make my second “hooligan” move.

Ovsienko V.V.: It says “5th of December 1980”.

Kravchenko V.O.: Thats right. However, I didnt plan any connections with the Constitution Day, that was just a coincidence. I came to Moscow having prepared a poster of “provocative and offensive character” (as it said in the sentence). The poster had the next text in it: “ L.I. Brezhnev! Do you want my blood? Come and get it then, you bloodsucker!” Of course, the text had been thought of ahead. I prepared a blade, especially for this occasion and the idea was to cut my hand so there would be a lot of blood and then unravel the poster so everybody would see it.

Having prepared all that I came to the Red Square next to the Cathedral of Saint Vasyliy. I chose a moment when the only person around was a KGB agent. I waited until he was also gone and then did my part.

I cut my arm but it didnt want to start bleeding at first because the cold was too strong so I cut it for the second time. My arm started bleeding then, so I unravelled the poster and raised it high above my head with my arm bleeding heavily. It wasnt long before two militiamen ran towards me from their post blowing their whistles and waving their hands at me. They approached me and retrieved my poster.

I didnt ty to evade them of course but when they tried to get my hands behind my back I politely said I will not do that, because it will make my coat dirty of blood. Then they took me to their post, looked at the poster again, and one of them addressed me: “Youll get into jail for this!” Well, if I must...

I was first taken to a militia department at Petrovka 38...

Ovsienko V.V.: You were arrested at 16:10. Thats what it says in the journal.

Kravchenko V.O.: They didnt even apply any bandage to me to stop the bleeding. Pre-trial interrogation, reasoning, etc. The next checkpoint was the psychiatric war for expertise.

Ovsienko V.V.: Serbskiy institute?

Kravchenko V.O.: I dont know. They kept me there for a long time beside people who were clearly mentally ill.

Ovsienko V.V.: How long did they keep you there?

Kravchenko V.O.: I dont know. Time is something I didnt think too much about. Then a doctor came and started talking to me.

Ovsienko V.V.: Did they treat your wound?

Kravchenko V.O.: No. The wound was still open and about 3-4cm wide. I cut it in a way not to hurt the muscles so I could see them clearly when the wound went wider with time.

So the psychiatrist came and started talking to me. I kept my tone and tact, like a diplomat, even though the doctors questions were sometimes very provocative. In cases of such provocative questions I simply replied that the doctors words lacked a logic line.

Ovsienko V.V.: You mean as if you were testing him, not the other way round?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. Although, he was doing it intentionally to check me. And I was clearly aware of what he was doing and what our conversation was.

Our chat ended as he asked me: “What should I do with you then?”. And I replied: “Youre asking me? Id say you should provide a clear and true state of my mental health” – “If so, then I shall say you are absolutely healthy”. And that was it.

I was then set free but first they took me to the nursery and bandaged my arm. On my way to the train station (as I had to return back to Kiev) I re-bandaged my arm. Made a better bandage so the authorities wouldnt have incriminated me self-mutilation if they had the chance.

Upon my return home I was called up again by Nikitchenko and told that if I wont write penance letter by the next day, I would be sentenced for imprisonment. I didnt write any penance letter and in a few days had visitors in civil clothes at my home.

Ovsienko V.V.: What was the date?

Kravchenko V.O.: 17th of of December 1980. They showed me a search order and kindly offered to surrender everything which they might find interesting. I knew perfectly well what they meant because I even knew they were following me around and getting inside my apartment when I was away. I gave them my manuscript. I didnt tell anything of it yet, but that was the reason I got incriminated with art.187-1 later on. They took it and arrested me. We travelled to their headquarters on Chervonoarmiyska street in Kiev and there they interrogated me and asked to sign some papers for the prosecutors order to send me on a judicial psycho-neurological expertise. That was the moment I felt danger. At first I decided not to sign it, but then figured that the authorities might write in anything they want into that blank space. I read the paper carefully and said that a doctor in Moscow concluded me as mentally healthy to which they told me that my actions forced them to check me thoroughly so they were sending me for an expertise to a hospital for full-time. I signed the paper but next to the signature wrote that I disagree with the treatment referral and that I oblige to take the treatment on ambulatory basis. I was then transferred to Pavlov hospital, investigation department No.13. This made everything clear – I was sanctioned by the prosecutor to be under investigation and am held in custody. However, it was also clear that all this was needed because my manuscript was being checked by some authority representatives, deciding my fate.

Ovsienko V.V.: Ive also been to department No.13, yes.

Kravchenko V.O.: Ive spent two months there.

Ovsienko V.V.: Who was doing the expertise? Natalia Maksymivna Vynarska?

Kravchenko V.O.: No, there was a man in my case – Mykhailo Dmytrovych.

Ovsienko V.V.: Lifshets?

Kravchenko V.O.: Lifshets was there later, after Id left. I think I was in jail when I heard that he was killed. You should remember, he was killed by some criminal during his expertise.

Ovsienko V.V.: Yes, Ive heard of it. Lets continue our conversation about the 16th of July.

Kravchenko V.O.: I would like to return to the subject of my manuscript which made me get art. 187-1 sentence. I started it back in 1972-73, but the interesting part is how I actually came to the idea of writing it. The trick is that this nonconformity of mine was, said to be against the Communism Party ideas as such. But to be honest, the only thing which was wrong was the superiority of the Party towards Komsomol, the DOSAAF and all the sport organizations like “Zenit”, “Spartak” and others. Creation of any other party would have made the Communist Party seen as nonsense. And this idea of a second party overwhelmed me at the time. I was sure that political contestation was something we needed.

So what should have a second party looked like? From my perspective it should have been almost identical to the current Communist Party with only one difference – the leadership role. Even the political campaign should have been the same as I had nothing against it. So if I had succeeded in creating a new Party, the communists would have gained their own followers again. Historical examples tell us that different political parties were created with people of the same class and similar views, so there shouldnt have been any problem with that. And bourgeoisie, as the class of owners also had their own parties, more than one. But then I thought that it would have been ok, because even just two partied with similar interests will split the people creating political contest among those wielding power. Such contestation should have cleansed the society.

These thoughts convinced me that my idea of two parties is normal and acceptable so I started formulating the actual idea. The political essence. I decided to write my thoughts down, so I could see them clearly and analyze but this didnt give any worthy result. I went to the library and took the Communism Manifest to study it and see how the thoughts in it were shaped. I read it a few times and tried to write down something of my own. This time I had a better result. I then read what I wrote but didnt really like it. I put my writings aside and returned to them later, checking, editing and adding new information. And so, step by step my manuscript was being created. After some time I came to a conclusion that I liked what I saw and that those ideas of two parties at contest for power or even of many parties doing so actually could exist.

However, after having done all that I realized that I had succeeded in walking a path on nonconformity and had become a dissident. I concluded that my thoughts should be written down, shaped into a novel. So I started writing again. It wasnt easy at first: sentences were all crooked and sharp but I kept writing.

Around 1974 I finished my work – wrote the last page. Total number of pages was around 800. That was the manuscript the authorities confiscated on 17th of December 1980.

Ovsienko V.V.: So it stayed in your apartment for all those years until your arrest without any action?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. It was first in the hostel where I lived, but my room mates didnt tell on me. I guess I chose my behavior correctly – didnt stress attention on it. I never hid it from them and always said that they could read it if they wanted, but they werent the kind of people who read a lot, so they didnt. I didnt continue writing because I got married in 1975, I was preparing to become a father so I had other things to do, even though I tried returning to this work a few times. I even found a lady (before my marriage) who lived on the left bank and agreed to print certain pages. I didnt have enough money to print them all so most of them stayed handwritten until the day of my arrest. If I had any options of publishing it anywhere, in the USSR or in the USA – I would have done it, even if it meant my imprisonment. I even offered my wife to read it but she wasnt the very into it. Its hard to read ones handwriting you know. After my rehabilitation and after the manuscript had been returned to me, she read it, yes, but only then.

Thats about everything, concerning my manuscript.

Ovsienko V.V.: So you actually retrieved it back then?

Kravchenko V.O.: I was rehabilitated around 1988, wrote an appeal to Zubets Georgiy Ivanovych, who sentenced me for imprisonment and then, as you might know, rehabilitated me (its a standard procedure – you are rehabilitated by the same judge who sentenced you).

Ovsienko V.V.: Valeriy Marchenko was rehabilitated by the same judge – Zubets.

Kravchenko V.O.: Our rehabilitation was a tough task, considering that the authorities didnt want to admit our criminal cases as their mistakes. But concerning the manuscript – I wrote to Zubets asking for my novel back because I wanted to work on it again. I thought that if I finished it then maybe I could even publish it somehow.

Zubets declined my request, of course, as did the head of Kiev City court. That was after we were rehabilitated together with Hmelevskiy Stanislav Borysovych and Anadenko Friedrich Pylypovych – they were also political prisoners. They also had something they wished to return upon their release so we tried to do it together but all failed. After all we addressed the Supreme Court of Ukraine which obliged the City court of Kiev to hand us our belongings. Zubets tried to hold us back as strongly as he could but in the end, thanks God, the Supreme Court of Ukraine influenced the events and we returned our handwritten texts. All three of us got what they wanted.

I started working on it. First I read this manuscript and made corrections to the text, but working on the text I asked my wife to make a typed version since she worked as a secretary.She did it for me and so I kept working with a printed text. The head of the Kiev regional organization of the Democratic Party, Karl Pavlovych Vasel, found a philologist at his work who edited my text. I asked her to make the corrections using a pencil. I looked it through, accepted some and didnt accept others, but in any case, this was the second step in the text work. Finally I asked Shkliar Vasil, who was once a member of the Republican Party, for help. He offered me Valeriy Nechyporenko as an editor who worked in the Economic newspaper. He was recommended as a writer and he was also a good editor. Moroz Konstantin Petrovich, a General of the Army, had a trustee – Mr. Kozak, he had a publishing house. Once we spoke with Pavlychko of my manuscript and Kozak heard it. Pavlichko talked about my manuscript in such manner that mr. Kozak became interested and offered to a computer version for me. I accepted his offer and had later acquired a computer version of the text, thus making me ready to publish it.

So the text is all edited and ready for publishing, and Im now looking for sponsors to publish it. Dmitry Pavlichko gave a very positive feedback on my book. By the way, I still havent told you the name – Road to dissident-ship – the name of the book. Michael Gorin read it on my request and had also given a very positive review. I remember an excerpt from that report: I do not know whether Mr. Kravchenko will succeed in publish his work, but in my opinion, this work is worth getting into the readers sight. In direct and sincere dialogues, internal monologues mr. Kravchenko managed to disclose the rebellion of a sensitive, uncorrupted soul standing against the stifling atmosphere elaborated by the communist regime just before the collapse of the worlds largest empire. And this is an excerpt from Pavlychkos response: But it is important that not only he suffered for his views, but that his views were prophetic. Today it would be very interesting to read the book by Valeriy Kravchenko in the form in which it was created. It will be a bestseller because it shows how the workers ideas lived in the darkest times which led to the collapse of unfailing Empire and the establishment of national and social justice. Ivan Zaets, Igor Yukhnovskiy, Lanovyi and Yemets Alexander, be blessed his memory, supported of the idea of publishing my book and I am very grateful to them for their support. (the book has been published: Valeriy Kravchenko. Road to dissident-ship.- K. : Yevshan zillia, 2008. - 436 p.).

Ovsienko V.V. .: But we completely omitted such an important matter as the arrest, investigation, trial and imprisonment.

Kravchenko V.O. .: As I said in the first part of my story, I was first taken to their, so to speak, office at Chervonoarmiyska street. I remember getting there in a black Volga. I remember one of the agents taking my briefcase and asking their commander about further instructions on it. “Seal it and send away to Moscow – was the answer. I think they knew of my work.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Have you ever thought of hiding it somewhere?

Kravchenko V.O. .: At first I hid it, in the beginning of my married life, but then I realized that for a long concealment I needed special conditions. For instance, burying it in a sealed package, but even then it would be getting some damage from moisture and the work would be lost. I was afraid of this and thought it best to keep it at home. Maybe it was my mistake, on one hand, but on the other hand, in the end everything was just as it should have been. This work has visited special depositories, it has stamps of the State Security Committee indicating that there are slanderous fictions against the Soviet system in it. These stamps are evidence that this manuscript hasnt been written today or yesterday. Im sure you came across situations during early freedom times when writers began showing off their works from the drawer, but the question is when were they actually put into that drawer? My manuscripts authenticity is out of question, the drawer it came from is the Kiev City Court.

Ovsienko V.V. .: And most importantly, it was well preserved there.

Kravchenko V.O. .: Well preserved, perhaps.There is no blessing in disguise. They even hemmed it there in order not to damage the manuscript.

Ovsienko V.V. .: Please tel of your arrest, the search, how did your family accept it. And the circumstances of the investigation. Accordingly, we must talk about the prison, about how you felt about it.

Kravchenko V.O. .: I was due on the second shift that day so in the morning I was at home. My wife was at work and the child was in kindergarten. So I was home alone. In the morning, around ten oclock, there was a knock on the door. I opened and saw people dressed in civil clothes, showing me search order. And then they offered me to give up everything they they might be interested in. I knew it wasnt hard to find it all so I gave it away on my own will. They calmed down after that but still confiscated my hunting rifle which I held at home on legal terms and my knives which were made by me personally. They incriminated me those knives according to art. 222 – “manufactury of weapons”.

Ovsienko V.V.: So they had some information about those knives, since they were searching for something special, right?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. But even according to their rules, if I manufactured those knives but never took them anywhere, they couldnt have been incriminated as art. 222 and so it didnt stop me getting rehabilitated later on.

So they took my briefcase and offered me to walk with them. Thats how I was arrested on 17th of December 1980. When we got out of the building I met my neighbor who was working in the same factory with me and asked him to pass on the message of my arrest. One of the agents murmured something illegible but definitely irritated. They made get into their black “Volga” and took me to their headquarters, which I told you about. After that they took me the Pavlov mental hospital. During the first few days of my imprisonment I had so many thoughts in my head that I actually got to understand why many criminal prisoners loose their minds during serving their sentences. You had your periods as a political prisoner, so you wouldnt understand.

Ovsienko V.V.: Yes, I would. I spent three years as a criminal prisoner.

Kravchenko V.O.: It felt that many people there had mental deviations. I personally, as all political prisoners, was aware of getting arrested, whereas criminals... they were sure theyd evade such fate.

I had my hard moments when I thought that I gave away my freedom too cheap. I was sure that the fight against totalitarian regime should be held in conspiracy, because as soon as one does an open gesture of disagreeing, he faces a line of discriminating actions against him. Its hard to oppose openly because you are sure to get imprisoned, but conspiracy opposition provides at least pale possibility of evading punishment.

I met many different people during my imprisonment. I was arrested on 17th of December 1980, but even before the New Year, the hospital got another newcomer. Criminal prisoners told me he was also a political prisoner. I went to meet him and found out that his name was Polishchuk Mykola Kindratovych, who originated from Bila Cerkva. He was preparing for strict regime imprisonment by art. 187-1 and was held among criminal prisoners. He was a conscious Ukrainian nationalist against forced Russification and spoke only Ukrainian. I should mention here that back then I spoke no Ukrainian, only Russian. I came to him and started talking, but he interrupted me and asked back: “How is it that your mother became a stepmother to you?”, I didnt understand what he meant and asked for explanation. “You are Ukrainian, judging from your surname, but you speak Russian”. I started explaining then, that I was born in Uzbekistan and wherever I went I heard only Russian. No Ukrainian.

We made good friends later on and had many conversations. He was like a breath of fresh air during my imprisonment in the hospital. He told me of his first imprisonment among criminal prisoners, about the beating. I sure you know how the guards lead criminal prisoners, making them do what the authorities want them to do. Criminals were ordered to beat him up for his Ukrainian language but when the guards asked the criminals of the reasons they beat him up, they said” “Because he doesnt abide our laws”.

Mykola Kindratovych prepared me a bit for my imprisonment, but my idea of conspiracy fighting was still there and I told him of it. He agreed after all and we planned to meet after our release.

After some time another interesting man was brought to the hospital for psycho-neurological expertise. He also had the 187-1 art. incriminated. Originated from Vatutino town, named Buzhenko Sergiy. I talked to him too and offered him to take part in the conspiracy fight after release, but he declined my offer. He had certain problems with his logic, which might have been the case because of influence of some criminal prisoner named Vasil, if I remember correctly. He decided to make it look as if he was insane to evade prison.

After Ukraine got its independence I tried to find him, even addressed the Vatutino militia department, but got no answer. I think he might have been an agent in disguise, but who knows.

These were the two interesting people I met before the actual imprisonment. Normally two-three weeks was enough to make a conclusion on whether the person was mentally ill, healthy or simulating illnesses, but I was held there for longer so I started asking questions. I had a felling that they could plan using some punishment medications on me as I was very inconvenient for Soviet authorities.

On 25th of February 1981 the doctor called me and told that they concluded me as totally healthy but offered me a compromise. If, and only if, I agree, they can write down that I have certain, slight, mental deviations according to which I can not be imprisoned. You will then have to spend some time here with us, but I promise that you will have no injections or other medications. You will then be released and free. I analyzed his offer right there, during our conversation and declined it, as such a record might be negative for my children in future.

And so I was then taken to Bogdana Hmelnitskogo square, where the preliminary imprisonment took place. I spent just three days there and then was taken to prison in Lukianovka district, where stayed until me sentence was executed on 6th of April 1981.

Ovsienko V.V.: Were you interrogated there?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. My first investigator was Anin, but then I had to sign a paper saying that my case is too large for one person so theyre passing it on to an investigation group. In the end, after all the interrogations and investigations, my manuscript was incriminated according to art. 187-1 – “Creation and distribution of slanderous ideas”.

Ovsienko V.V.: Distribution? What distribution?

Kravchenko V.O.: There was no! Yes! But I was incriminated this article, as were many other dissidents, with no account of this small detail. The main idea was – if you think differently, you will be punished.

I confessed to be guilty and started explaining that I understood my faults. I said agreed to start changing but never said anything about repentance. But nevertheless, I served my full term, didnt get an amnesty and was released under administrative supervision. I had to come and check in, my home was getting searched from time to time. And I had to be home by 18:00.

Ovsienko V.V.: That early?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. I had to stay home from 18:00 to 06:00. They even allowed me to visit mother-in-law who lived out of Kiev, on one condition – I had to check in, write an appeal saying where I was going, and then I could go. I was forbidden to visit parks, restaurants or cinemas.

Ovsienko V.V.: How long did this administrative supervision last for?

Kravchenko V.O.: For a year. But then I realized that the supervision stayed but was now discreet. I found out because they came to the factory once, asking around about me and my doings.

I missed a point in my story. Upon my release I tried to get a job at the “Arsenal”, but was refused. I was, however, accepted to the “Lenin Forge”. They did it because they considered my conviction art. 206-2 – “hooliganism” as nothing too serious. They didnt pay attention to the conviction art. 187-1, so I was just a little hooligan for them.

Ovsienko V.V.: We missed the imprisonment again though. How did it go? Did you you apply for cassation appeal?

Kravchenko V.O.: I dont remember anything about the cassation appeal... I do remember though that the appeal took place and was reviewed. The imprisonment term stayed the same however.

Ovsienko V.V.: Where did they take you?

Kravchenko V.O.: I spent around a month in the so-called “trial department”. After that I was taken to the shift through Kharkiv and Luhansk to Komunarsk, to medium security prison. I stayed there for the first part of my term and worked as a turner.

Ovsienko V.V.: How did that environment take you?

Kravchenko V.O.: Well, I didnt have any difficulties because I found a job. Although I went on a hunger strike once because the guards forbid me to grow a beard. I even wrote an appeal to the court claiming my right to grow a beard as I was a political prisoner. Later I understood that it was a wrong move.

Ovsienko V.V.: Were you punished for it?

Kravchenko V.O.: No, I wasnt. I just had my beard shaved away straight after imprisonment.

Ovsienko V.V.: So that was before the prison.

Kravchenko V.O.: I think it was in the Kiev prison. I must say that all these shifts and the chronology of all situations was something I didnt give much attention to.

Ovsienko V.V.: Did you feel any special custody from the administration or some operative worker, because you were quite deviant for that camp? I guess you were unique.

Kravchenko V.O.: No special custody. However, when I came to the prison in Komunarsk I was asked by one of the soldiers: “Is true that your prison just got a new anti-soviet prisoner?” So I thought that word of me travels faster than I do.

I was then called up for conversations. Of course I was persona non grata for the local prison commander so I was being carefully watched and examined. However, after my hunger strike I was holding myself back not to do silly things.

Ovsienko V.V.: Was your relationship with others equal?

Kravchenko V.O.: I was trying to diffuse among others. I saw my location as normal for a politically inconvenient person in such society. I realized that I should simply embrace myself and go through this with minimum loss. I also came to a conclusion that all my contacts and acquaintances with American representatives had no power and no influence. SO i just felt that I needed to live it through.

So I lived like that until Brezhnevs death. We heard rumors that the prison in Lukianovka district of Kiev chanted “Hurray!” after the news. In a week or two I had been shifted again. I connected that with Brezhnevs death for myself. They moved me to Sokyriany of Chernivci region, where I stayed until the end of term inside a prison with intense regime.

I must say though: Kiev prison had awful food. In Kharkiv and Luhansk the food was better, but still, it was just ordinary skilly. In Khmelnytsk, Ivano-Frankivsk and Chernivci region – the difference was immense. There was actually some fat in the meal and sort of a first dish.

At first, they gave a turners job there, but I volunteered for the mines.

Ovsienko V.V.: What was the mine?

Kravchenko V.O.: Wall stone mines. It payed off better and I needed money to feed my wife, who had just given birth to a second child and couldnt attend work. Mines could give around 130 RUR, but the government took away a half automatically, since it was prison work.

It didnt work out in the end, but during my work at the mine I also attended electric welders courses. I learned to do that and started making gates instead of mining. Those were my doings in Sokyrniaky prison.

Ovsienko V.V.: Was it hard for you?

Kravchenko V.O.: Working in the mines was a nightmare.

Ovsienko V.V.: It must have been really dusty.

Kravchenko V.O.: Dust is one thing, yes. But it was physically hard to cope with. My back was aching all the time from carrying 40-50 kilograms of weight every time.

Ovsienko V.V.: Why did you have to carry 40-50 kilograms in one go? Couldnt you have done it in three?

Kravchenko V.O.: The machines working there were cutting the rocks in three vertically, so all people who worked there had to take three stones in one go, because if I took only two, for example, someone had to take my third stone or it fell to the ground. So according to the technology of the process, each person had to grab three stones at a time and that was around the eight I mentioned.

Ovsienko V.V.: Could you take a rest?

Kravchenko V.O.: Basically, no. The process was built in such a way that when you dont carry stones you have to shovel sand away from the machine to keep it working. A lot of physical tension. However, those who worked in the mine had better food – meat, for example. I worked there for some time, but obly long enough to graduate from electric welding courses.

Ovsienko V.V.: I have a question, Have you ever met Josef Ziselc there? He served his sentence in the same prison until December 1981.

Kravchenko V.O.: I heard of him, yes. I even wrote him a letter, but it was my mistake.

Ovsienko V.V.: So you werent in one prison at the same time?

Kravchenko V.O.: I have a feeling that the KGB was aimed at keeping political prisoners apart in prisons. Although, criminal prisoners had told me of Josef, who was there about a year before me.

Ovsienko V.V.: So you were released on time then. Were you released straight out of the prison or after a shift home?

Kravchenko V.O.: I was released right away from the prison. I even stayed a day longer and told the administration of this fact, but they said that this happened because one day fell out during my stay at neuropsychiatric expertise back at the hospital. I decided not to quarrel about this.

Ovsienko V.V.: So, you were arrested on 17th of December 1980 and then released on 18th of December 1984?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. I first traveled to the closest town – Sokyriany where I took a freight train home, because the public train had some engine problems. During the journey a militiaman came in to check my documents, because, I guess, the train driver notified the militia of my presence, just in case I was a runaway.

Ovsienko V.V.: They didnt take you off the train?

Kravchenko V.O.: No. I got to Chernivci and had the opportunity to see how strongly was the system going down in its self destruction. A militiaman, who was in the same carriage with me got drunk and was openly flirting with the conductor lady, who was obviously of easy virtue. Then he confiscated my release notification so I had to apply for duplicate later in Kiev.

Ovsienko V.V.: Did you have civil clothes on you or were given something back at the prison?

Kravchenko V.O.: I was traveling in prison clothes.

Ovsienko V.V.: In black. So he noticed you right away.

Kravchenko V.O.: Of course.

Ovsienko V.V.: That was before Perestroika so you probably had difficulties with getting a job. You mentioned that you were declined a job at the “Arsenal” factory, yes?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes, but I should mention that the April plenum had already taken place in 1984, but that was just the beginning.

Ovsienko V.V.: Gorbachev came to power later on 2nd of April 1985.

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes, so at the time Chernenk was still the head of the Soviet.

Ovsienko V.V.: How did you feel about Perestroika? Did have any hopes for it? How did society meet it?

Kravchenko V.O.: The idea of conspiracy opposition was still there. But to be honest I started feeling the changes when “Pravda” newspaper published an article in December with light criticism of Brezhnev. And after the XIXth conference of the Party...

Ovsienko V.V.: That was after Gorbachev came to power.

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes, and that was already Yeltsins time. I felt that the changes were on and they were coming from the top, from inside the communist party. It made me think and I decided to apply for Party membership to influence the changes somehow. That was after my rehabilitation but before the Movement took place. When the movement started, however, I decided that conspiracy is no longer a good idea.

Ovsienko V.V.: So you cancelled the idea?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. I cancelled both – the conspiracy idea and rehabilitating in the Party. I came to the Writers and started looking for Yavorskiy, whose speech I heard on TV and considered him a very open and courageous person. I acquired his phone number at the s headquarters and called him. I told him who I was and said that I was very much into his idea of creating the Movement. I offered him to meet, but he didnt feel too excited about it. He said: “Why should we meet? What will we be saying to each other? Expressing gratitude on having equal ideas?”. Back then I thought he didnt want to have anything to do with a former prisoner not to have weak points in the social picture of the Movement.

Soon after that I saw a discussion between Kravchuk and Popovych on TV and thought that it was impossible to have no need of a laborers view inside National Movement like that. So I headed to the again, seeking the Movement initiators. I must say that at first they addressed me with caution because of my Russian language. During my first visit there I saw a hive buzzing and all active, tasting revolutionary thoughts, but when I came there for the second time I clearly saw that the Central Committee of the Communist Party had already been there with advises because all the people inside the were much more quiet and calm. I asked for the initiators of the Movement and found a man named Ivan Drach. I explained who I was and as soon as I said that I worked at the “Lenin Forge” his face changed into grimace. “Are you here to join or to quarrel?” – he asked, and I understood his grimace then. I said I was there to help and he became much more friendly after that and offered me into his office. I told him of my short conversation with Yavorskiy and that I was wondering whether they even needed any support. He said they did and told me to an organization among the workers at the factory. He became very open and friendly when I agreed to that.

Ovsienko V.V.: That was after the first variant of Movements actions had been published? On 16th of January 1989 in the “Literaturna Ukraina” journal.

Kravchenko V.O.: No, that was before the publication, it was back in autumn of 1988. I started creating an organization of workers among those who worked at the “Lenin Forge”. It was obvious that people wanted changes and saw that they were needed. So we created an organization in the 12th department of the “Lenin Forge” and started openly agitating people to support us. We created a protocol on my initiative and started collecting signatures. That was the first step.

After that we conducted a gathering and created the Movements organization at the factory officially, so I started visiting other factory departments to find more followers. In two or three departments my agitation gave results. Later on the factory communist committee started calling me up to get acquainted better, as they said, but the truth was that they simply didnt know what to do. They were lost and scared.

But then, our 12th department had a visitor in the person of the chief secretary of the communist party committee of the factory. He came to gather a meeting of communists from workers and to stand against the Movements ideas.We also came to that meeting to oppose them. It was a tough run and we lost just two votes. So they kind owon their position fare and square, but we just said that they may keep their views and we will keep our views and our position.

Another significant action after that was the half-conspiracy meeting of the Movements members which the newspaper “Vechirka” wrote about. Viacheslav Briukhovetskiy was the one who wrote of it saying that it was a meeting of the National Ukrainian Movement for Perestroika. On that meeting they chose more than half of the future co-leaders of the Movement: Myroslav Popovych, Ivan Drach, Vyacheslav Briukhovetskiy, Vitaliy Donchyk, Petro Golod, Larysa Skoryk. They had also created a coordination council, whose members later became deputies. It was such a great time back then, we stayed together late in the evening, openly and passionately discussing possibilities and plans.

I also became a member of the coordination council, preparing the inaugural conference. Apart from that there were thoughts about getting me back to the “Arsenal” since I was rehabilitated and people had to see it. In addition to that, the “Lenin Forge” factory already had its Movement organization, so now it was time for me to another one at the “Arsenal”. The most important thing for me, however, was to get back in line for acquiring an apartment since I was rehabilitated and had the right.

I applied to the “Arsenal” and the HR department representative said I was all good to get in. I left the “Lenin Forge” and had a month off, because I wasnt suited for a vacation at the “Arsenal”, so I had a legal month to be free. The Movements inaugural conference took place during that month and I made a speech there as a labor class representative. It was a good speech, the TV representatives liked it and I was even shown on Ukrainian television. However, “Arsenal” administration also saw it, and when I came to them after that month, they denied me my work place.

Ovsienko V.V.: So you left one place, but were denied the other.

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes. Not a very nice situation. I addressed the court, since the changes were already happening. I decided to sue the factory, on the basis that they want to deny me job place since I was a rehabilitated prisoner. I remember that trial, the “Arsenal” representative was claiming that I missed the time gap to apply for the job, and then a deputy, Gryshchuk Valeriy Pavlovych helped me out in that situation. He used his authority and wrote a claim on his deputy blank, addressing the judge and concerning my situation. It was strange, he wrote, that there were numerous vacancy adverts of turners needed at the “Arsenal”, but for some reason the factory didnt want to take a rehabilitated turner who was ready to work. The court decided the case in my favor but the “Arsenal” still didnt want to the argument. They applied for a cassation appeal on the courts decision and the prosecutor, on his behalf applied to cancel the Kiev City Courts decision on my case.

Ovsienko V.V.: Its interesting, what arguments did they use?

Kravchenko V.O.: One of them was that the factory didnt want an active Movement member as their worker.

Ovsienko V.V.: Officially?

Kravchenko V.O.: Well, of course they didnt tell me this. But that was a real reason, since they saw me on TV. The absurd of this situation was that the Supreme Court of Ukraine was dealing with an appeal concerning a worker who wanted to work at a factory. The Prosecutors office, together with the Supreme Court decided the case in my favor, this should be mentioned. Besides, I prepared for the trial very thoroughly. I collected all the documents, read everything needed to understand the way the trial goes. I was well prepared, as aI said, so all the lunges of Pashenko – the “Arsenals” defender, were easily parried by me during the hearing.

As a result of his little lie and my reply, I one the hearing from A to Z. I was given everything I asked for including a job, and compensation for the inconvenience.

On the first working day I was all surrounded by people asking me about the hearing and the administration only stood aside silently looking at Kravchenko all surrounded by people and victorious.

What happened later was even better, because a few people approached me and asked to come to their department and tell of the Movements ideas and plans. Of course, I agreed. I came to the needed department and read my sentence to them, about the situation which took place at the Red Square, about the trial on my imprisonment. The “Arsenals” administration was listening to this all scared and not knowing what to do.

As a result of this, we created the Movements organization at the “Arsenal” too.

Ovsienko V.V.: That was after the Movements gathering?

Kravchenko V.O.: Yes.

Ovsienko V.V.: It took place on 8th-10th of September 1989.

Kravchenko V.O.: I wouldnt tell as I dont remember. So, there was an organization at the “Arsenal” after that and I was one of the co-leaders of the Movement, together with Pavlichenko and Golovatiy. And thats my story.

Ovsienko V.V.: A very interesting story that is. Could you sum it up to modern days? Just in short.

Kravchenko V.O.: Ok. Mass protests, hunger strikes of Polytechnic Institute students, that was during my membership in the Movement. It was all very scary for the communists. I remember the article called “Two views at one problem” overviewing the thoughts of Ivan Drach on one side and Leonid Kravchuk on the other. I remember that Drach was asked whether the Movement was the next Party, to which he answered that this organization was of too many different colors. It had former communists in it, political prisoners, members of the Ukrainian Helsinki human rights Group, so it was highly doubtable that it could actually become a political party. It was just a wave, a public organization, which couldnt have become a party.

The first idea of a party came up with the name of Democratic party of Ukraine. Then there was the idea of the Ukrainian Republican party. But I personally think it would have been better to a Democratic party, but again, thats just a personal opinion. When talks of creating a party got louder I had an image of a party containing central Movements representatives in it – something in the middle between communists and radicals. I imagined that Drach, Briukhovetskiy, Popvych, Horyn, Lukianenko, you, Horbal – all those I already knew by that time, will all be in one political party.

So I started taking part in the creation of the Democratic party of Ukraine. I addressed the “Arsenals” Movement members for support and some of them agreed. We created the party in its initial form, without any materials yet, and started working on its creation. I couldnt be present at the first official gathering of the Democratic party of Ukraine because my father was dying right then, so I went to be with him. He died on the 12th of December and I stayed for his funeral. In my absence they chose me to be part of the Natinoal council of the party, thus making the Democratic party of Ukraine a part of my life. Thats the way it has been for the last 20 years.

Ovsienko V.V.: So you still work there, even after you stopped working at the factory?

Kravchenko V.O.: I stopped working at the factory back in 1992.

Ovsienko V.V.: If you could name your wifes name and you childrens names, it sould be really nice.

Kravchenko V.O.: My oldest son was born on 14th of May 1976, named Oleksiy. Younger son – Andriy, was born after my arrest, on 25th of June 1981.

Ovsienko V.V.: And you wife?