January 12th marks the 50th anniversary of the greatest repressive action against Ukrainian dissidents, when the majority of prominent representatives of the national-democratic movement were simultaneously arrested and the so-called "general pogrom" of Ukrainian sixtiers movement began.

The primary means of struggle by the sixtiers against the totalitarian regime was samizdat. From 1965-1972, Ukrainian samizdat consisted of artistic works, documents, and journalism. It vividly reflects the history of resistance of those years, while simultaneously representing an integral part of it.

From January 1970, the first periodical publication in Ukraine began appearing in samizdat – "Ukrainian Herald" (UH), modeled after Moscow's "Chronicle of Current Events" (CCE). But unlike CCE, UH contained not only information about repressions and the situation of political prisoners, but also presented works distributed in samizdat – historical research, data on the genocide of Ukrainians, literary studies, poetry, and prose. The publication was characterized by a high professional standard.

UH was created on the initiative of Vyacheslav Chornovil, who became the chief editor of this journal. The editorial board also included Mykhailo Kosiv and Yaroslav Kendzior[1]. A large number of dissidents actively participated in distributing UH. UH was also transmitted abroad.

Attitudes toward publishing UH were ambiguous. According to Leonida Svitlychna, Ivan Svitlychny, when UH began publication, actively distributed it, but he was against the idea of publishing UH, believing that this would accelerate arrests. Subsequent events showed that he was right[2].

Vasyl Ovsiyenko recounts: "With the fifth issue, 'Ukrainian Herald' was cut short – it was stopped in mid-1971, because rumors began circulating that arrests would begin soon, and the head of the KGB of Ukraine, Vitaliy Nikitchenko himself, had a conversation with Ivan Svitlychny and said: 'As long as you weren't organized, we tolerated you. From now on, when you have a journal, we will not tolerate you.' It was decided to stop publication of the 'Ukrainian Herald,' but it was already too late"[3].

On June 28, 1971, the Central Committee of the CPSU adopted a secret resolution "On Measures to Counter the Illegal Distribution of Anti-Soviet and Other Politically Harmful Materials," which was duplicated a month later by the Central Committee of the CPU, adding local specifics. The Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU on December 30, 1971, resolved to begin an all-Union campaign against samizdat with the aim of destroying the infrastructure of its production and distribution. The party leadership of the Ukrainian SSR, headed by Petro Shelest, supported Moscow's initiative, because it actually no longer had power in the republic and was completely controlled by the Kremlin [4].

The repressions of 1972 were an empire-wide action. In Moscow and Novosibirsk, arrests took place in connection with the "CCE case." For the Ukrainian movement, a separate detective story with "spy passions" was staged – the so-called "Dobosh case".

On January 4, 1972, Belgian citizen and tourist Yaroslav Dobosh, a Ukrainian by origin, was arrested. He was "processed" and forced to confess that he had arrived "to carry out the assignment of a foreign anti-Soviet center of Banderite OUN." Many dissidents had a different opinion about this – that Dobosh had been recruited by the KGB in advance. But this assertion probably does not withstand criticism.

Here is what Vasyl Ovsiyenko recalls about this: "As is known, before the New Year 1972, Yaroslav Dobosh came to Ukraine. He was a member of SUM, from Belgium, 25 years old. He traveled through Prague. I know that my classmate Anna Kotsur, a Lemko from Slovakia, went to Prague for New Year's. She had a meeting with Dobosh there, which I learned about later. She gave him the telephone numbers of Lviv and Kyiv sixtiers, including Ivan Svitlychny. It was precisely using these telephone numbers that he called Svitlychny in Kyiv, and someone else there, and then met with Svitlychny and other people... Later, when I was arrested, I read Yaroslav Dobosh's testimony and concluded that this was probably an accidental person. I'm not sure whether he was really recruited by the KGB, or whether it was just out of his naivety that he was interested, whether he had some assignment from his superiors or not – God knows. But the KGB used him quite successfully. He told everything he knew and didn't know, made a statement on television, and that statement was published in the press. He was released, and all this became a pretext for mass arrests of Ukrainian intelligentsia"[5].

The arrests of January 1972 were somehow connected to the Y. Dobosh case. Dobosh himself, after his confession, was expelled abroad, where he refuted his testimony, but this was no longer paid attention to.

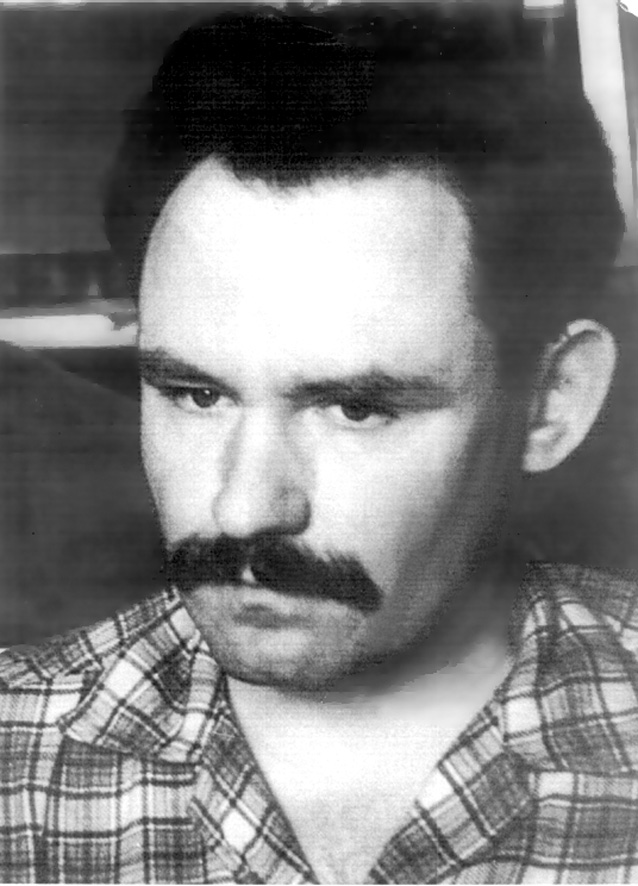

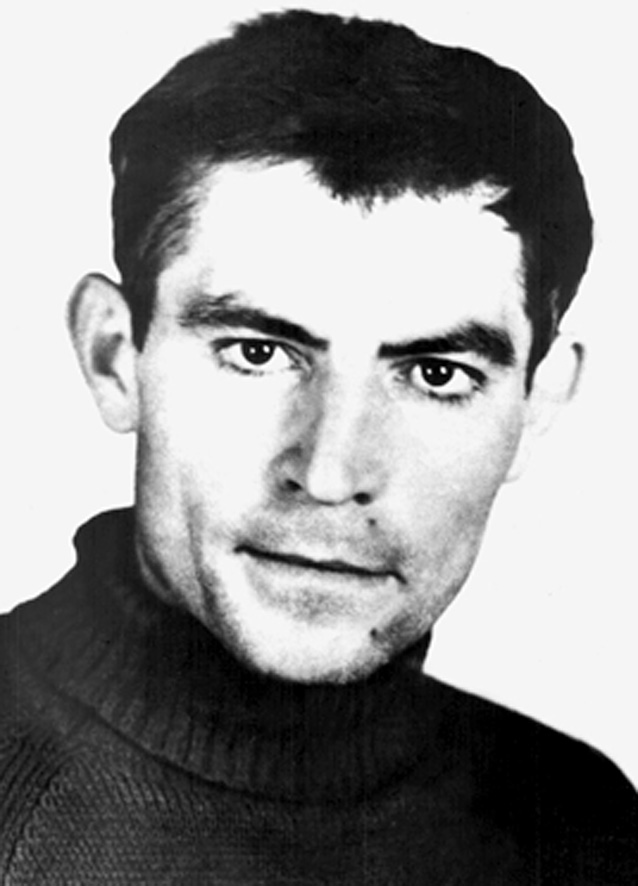

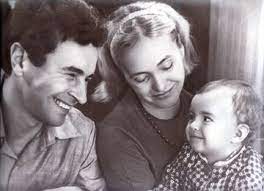

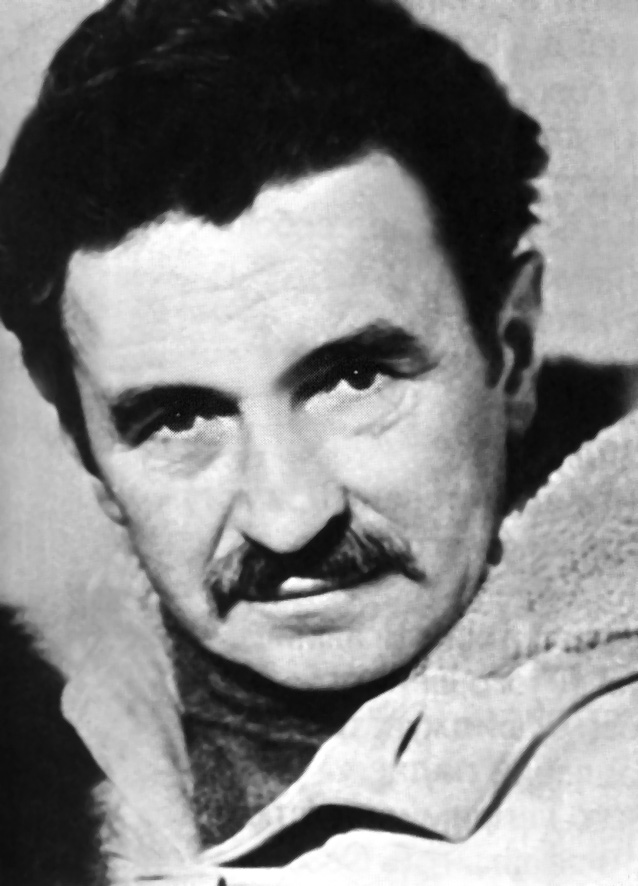

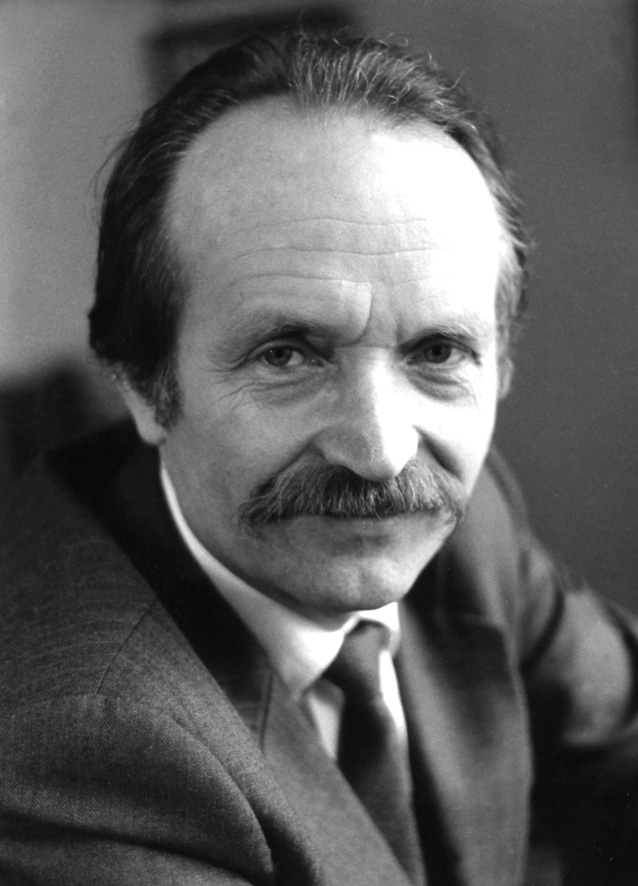

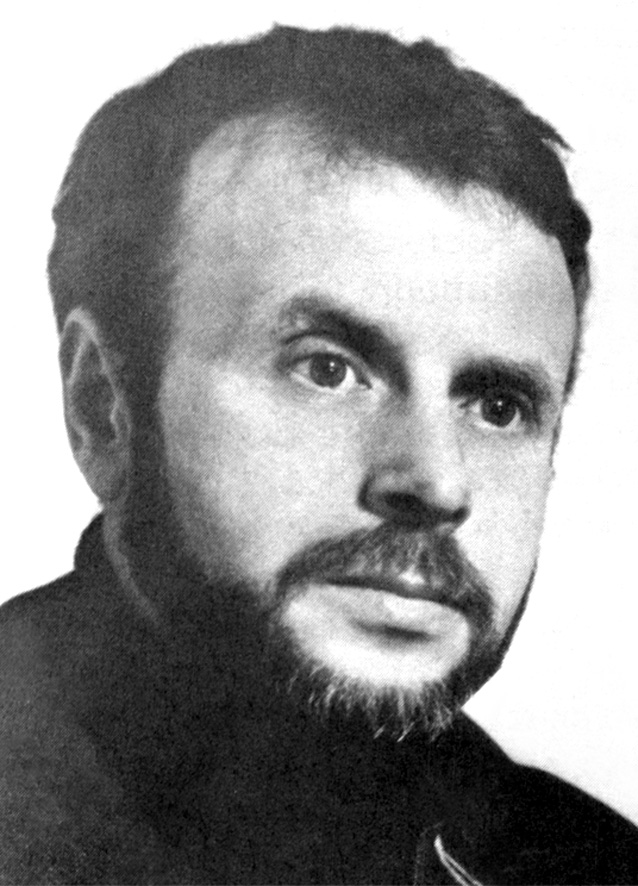

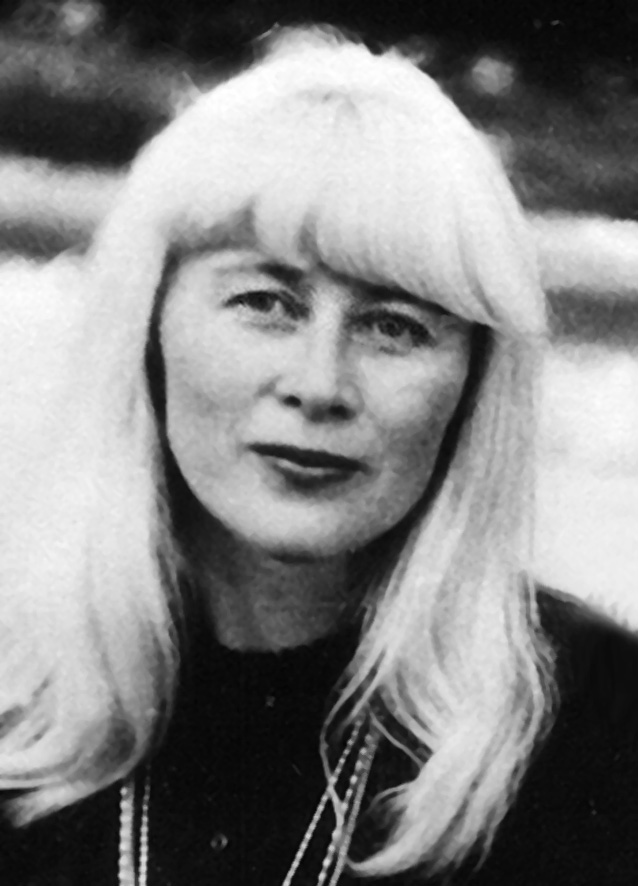

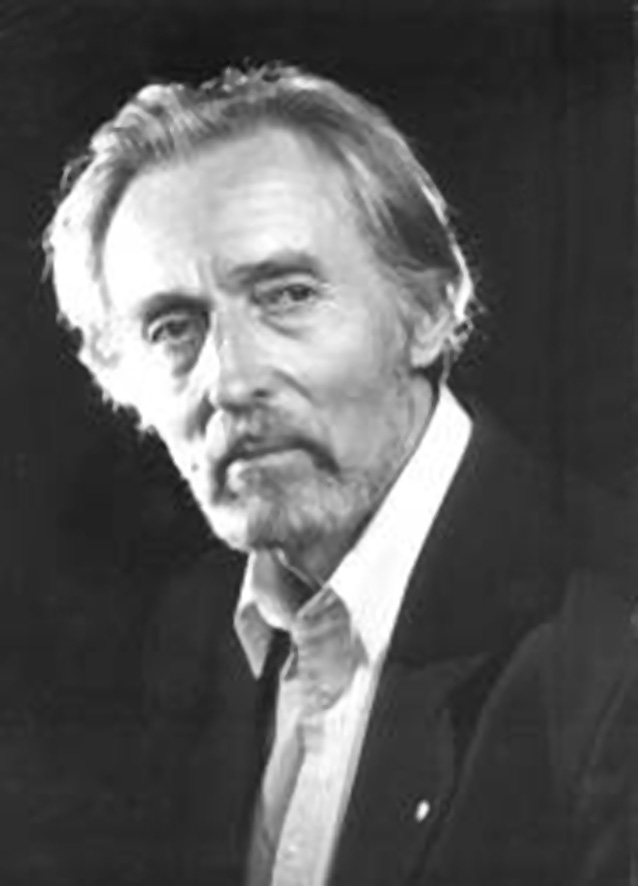

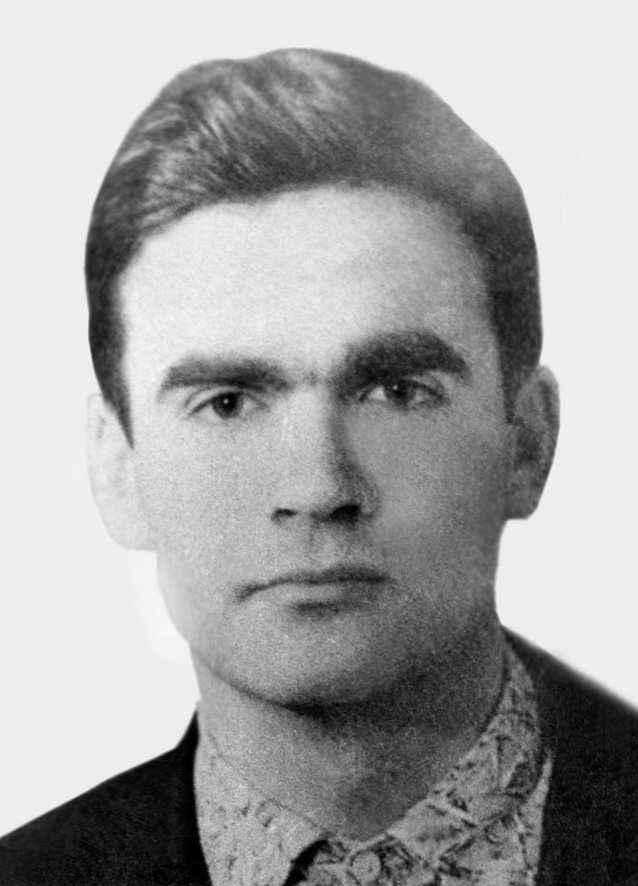

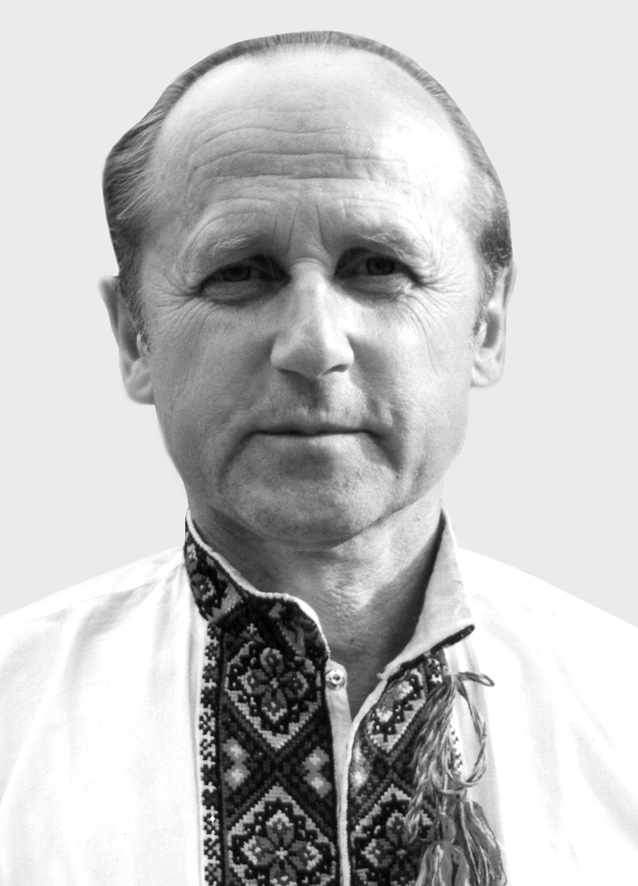

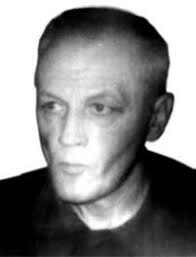

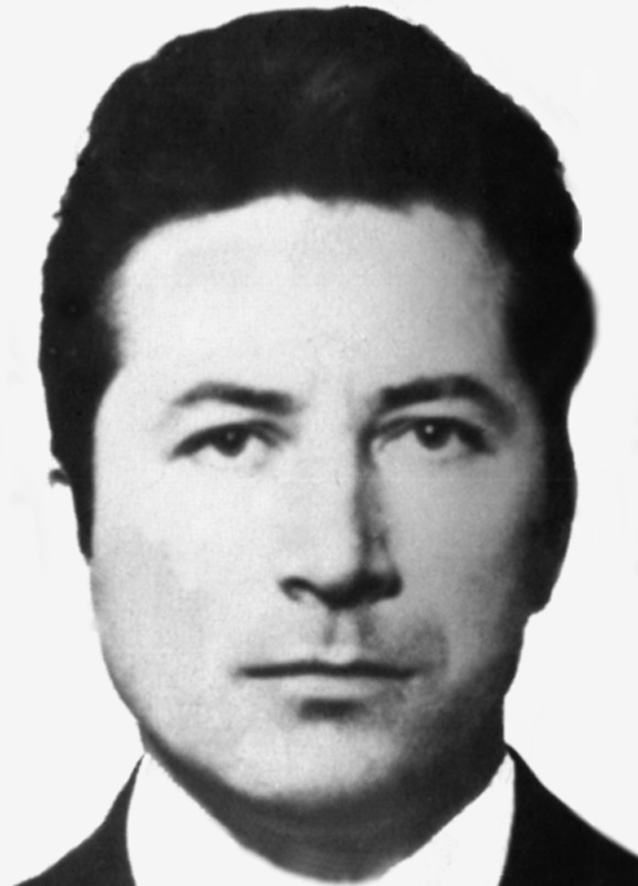

From January 12-20, 1972, prominent dissidents were arrested: in Kyiv – Ivan Svitlychny, Yevhen Sverstyuk, Vasyl Stus, Leonid Plyushch, Zinoviy Antonyuk, Mykola Plakhotnyuk, Ivan Kovalenko, Oles Serhiyenko and others; in the Kyiv region – Danylo Shumuk; in Lviv – Vyacheslav Chornovil, Mykhailo Osadchy, Ivan Hel, Iryna Stasiv-Kalynets, Stefaniya Shabatura; in Ivano-Frankivsk region – Vasyl Romanyuk (future Patriarch Volodymyr); in February, Yuriy Shukhevych and Mykola Kholodny were imprisoned. The next wave of arrests occurred in April-June 1972: Ivan Dzyuba and Nadiya Svitlychna were arrested in Kyiv, Ihor Kalynets in Lviv, Ihor Kravtsiv and Anatoliy Zdorovyy in Kharkiv, and others.

After many days of interrogation, Zinoviya Franko (granddaughter of Ivan Franko) admitted that Dobosh was an agent and that the sixtiers had contact with him. Generally, this was part of the KGB's plan – to force the granddaughter of Ivan Franko – Zinoviya Franko and the niece of Mykhailo Kotsyubynsky – Mykhaylyna Kotsyubynska to "confess" and "sincerely repent." A television appearance by these two ladies, influential in dissident circles, would have dealt a decisive blow to the sixtiers movement.

"Zenya Franko was immediately imprisoned in January 1972, and they took me on somewhere in March," – recalls Mykhaylyna Kotsyubynska. – "And I very quickly understood the plan that had matured in them. The plan was this: to combine my name with Franko and put us on television together. You can imagine how much stronger this would have sounded than just Zenya Franko's appearance on television. She was there, she was there, and I was repressed. Her letter was in 'Soviet Ukraine' – but mine wasn't"[6].

Mykhaylyna Kotsyubynska broke this plan, despite all the threats and cunning of the KGB. Neither confrontations with Z. Franko helped, nor even threats to take away her daughter and deprive M. Kotsyubynska of maternal rights.

During the investigation, the arrested were threatened with execution, physical violence, treatment in special psychiatric hospitals, and most importantly – violence against loved ones. However, among the key figures, except for Ivan Dzyuba, no one repented. Dzyuba was "broken" from April 1972 to October 1973. On March 16, 1973, he was sentenced to 5 years imprisonment and 5 years exile. On October 8, I. Dzyuba wrote a petition for pardon. The authorities satisfied the request. This was advantageous to them (one of the leaders of the resistance movement, author of the programmatic work "Internationalism or Russification?" admitted his mistakes). It should be noted that I. Dzyuba wrote exclusively about his own convictions and gave no testimony against his friends during interrogations.

On May 26, 1972, P. Shelest was dismissed from the position of First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPU, and V. Shcherbytsky took his place. In a short time, Shelest's entire "team" was removed from power in the republic. Their place was taken by chauvinist reactionaries – obedient children of Moscow.

Meanwhile, in summer and autumn 1972, court trials took place. Almost all leading figures of the sixtiers movement received the maximum sentence under the notorious Article 62 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (7 years imprisonment in strict regime camps and 5 years exile) and were transported beyond the borders of the Motherland – to Mordovia and later to Perm region. Those who gave no testimony (Mykola Plakhotnyuk, Leonid Plyushch, Borys Kovhar, Vasyl Ruban) were committed to psychiatric hospitals.

Overall in Ukraine in 1972, according to CCE data, 100 people were arrested[7]. According to Lyudmila Alekseyeva's data, 89 people were convicted. From Western Ukraine – 55 (of which 13 from Lviv). From Eastern and Central Ukraine – 48 (of which 28 from Kyiv)[8]. From 1972-1974, more than 122 people were arrested for participation in the Ukrainian national-democratic movement[9]. According to the latest data from the Kharkiv Human Rights Group, 193 people were arrested in Ukraine in 1972-1974, including 100 people for anti-Soviet propaganda and 27 people for religious beliefs. Starting from January 12, 1972, during this period in Ukraine, thousands of searches were conducted, thousands of people were terrorized by interrogations as witnesses, fired from work, expelled from universities. Isolated attempts to protest against the arrests were suppressed most ruthlessly (Vasyl Lisovy, Mykola Lukash).

The social atmosphere, unlike the atmosphere after the first wave of arrests in 1965, became oppressive. Everyone who did not give testimony against the arrested and showed the slightest signs of sympathy for them was fired from work, expelled from institutes, and had any possibilities for career advancement and creative publication (publications, exhibitions, etc.) closed to them. Just as the renaissance of the 20s is rightly called shot, so the renaissance of the 60s was strangled. Those who wanted to survive had to repent humiliatingly (Zinoviya Franko, Mykola Kholodny, Leonid Seleznenko, Ivan Dzyuba), others wrote hypocritical lampoons against their recent friends or foreign "Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists – mercenaries of foreign intelligence services," squeezed false odes out of themselves in honor of the stranglers of their homeland (Ivan Drach, Dmytro Pavlychko), some could not withstand the suffocating atmosphere and became alcoholics, committed suicide (Hryhor Tyutyunnyk), the most resilient went into long-term "internal emigration" (Lina Kostenko, Mykhaylyna Kotsyubynska, Valeriy Shevchuk), or actually emigrated to Russia (Les Tanyuk, Pavlo Movchan).

The general pogrom of 1972 stopped the development of the sixtiers movement and simultaneously became the foundation of a new era in the history of the resistance movement. In reality, the action against samizdat was only partially successful. The distribution of samizdat significantly decreased for some time. It ceased to be the main means of struggle against the totalitarian regime. At liberty after the arrests of January 1972, there were attempts to continue publishing the "Ukrainian Herald." In Lviv, issue 6 of UH appeared, prepared by Mykhailo Kosiv, Yaroslav Kendzior, and Atena Pashko. This issue of UH was called "Lviv," because almost parallel to it, in March 1972, in Kyiv, Vasyl Lisovy, Yevhen Pronyuk, and Vasyl Ovsiyenko published a special issue of UH with information about the arrests, also numbered 6. Vasyl Lisovy wrote an open letter to members of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Central Committee of the CPU, after which he was arrested, then Yevhen Pronyuk was arrested, and Vasyl Ovsiyenko was arrested 8 months later, in March 1973.

More conspiratorial was Stepan Khmara's group, which also compiled UH: issues 7-9 in 1974-1975. Besides Khmara, this work was done by Oles Shevchenko, Vitaliy Shevchenko, and Vasyl Karabik. This group was even closer to the underground movement than to the sixtiers: both in the political content of materials and in conspiracy methods. Issues 7-8 reached abroad on photographic film. Stepan Khmara and others were arrested only in 1980. The general pogrom almost suspended the dissident movement in the "large zone," but only raised the spirit of resistance among the imprisoned. Some dissidents themselves recall that, strangely enough, the time spent in captivity – in the "small zone" – was the most interesting and even the best period of their lives. Mykola Horbal recounts: "When I met Svitlychny already in the Urals, then with Antonyuk, got acquainted with Valeriy [Marchenko], I was never so liberated, never had so much humor, and never laughed so much as in the camp... I gave myself my word that I would never complain to God, because God knows better which paths to lead us on. I repeat this phrase often, so that perhaps people know that one should not complain about fate. Because if such a path is determined for you, then apparently, that's how it should be. Having then a second trial, I always remembered this, having then a third trial... And this saved me. When they didn't release me from the second imprisonment for the third time, but tried me for the third time, I think to myself: God, well what is this? Well, I survived these terms – so it must be necessary. And when they put me in a cell with Semen Skalich, I even think to myself: God, to hear all this – these revelations from this man, I had to get into this cell, and to get in, I had to receive a term!"[10]Ihor Kalynets recalls about this: "In the camp it was physically difficult for us. Let's say, we were separated from our native land, from family, from the dearest ones. Communication was difficult. We were in a very dramatic situation when your elderly mother or little daughter comes to visit you, and they travel several thousand kilometers, but they don't give you that meeting, everything falls through. This was hard to bear. But on the other hand, we were somehow free, spiritually free. We, let's say, threw off that mask that we wore there, in that society, before arrest. Because there it was still necessary to pretend that you are not, so to speak, a bourgeois nationalist, that you are not an enemy of Soviet power – that you are a Soviet person, but you think that policy is not conducted correctly here in national or some other respect"[11].

After the "general pogrom," the resistance movement was reborn in the second half of the 70s, when institutionalized human rights defense became the main means of struggle against the system.

Much has changed since those times, much remains, unfortunately, unchanged, but there is no longer fear – it was destroyed by those brave people in the distant 70s-80s of the last century, who went to prison for the right to call things by their proper names. The sixtiers destroyed the utopia about "new" Soviet culture, about the "new" Soviet person and returned to words and concepts their natural understanding; they returned universal human values: faith in God, the desire for freedom, mercy, dignity. And today we must learn their main lessons: never betray our values and daily defend our freedom.

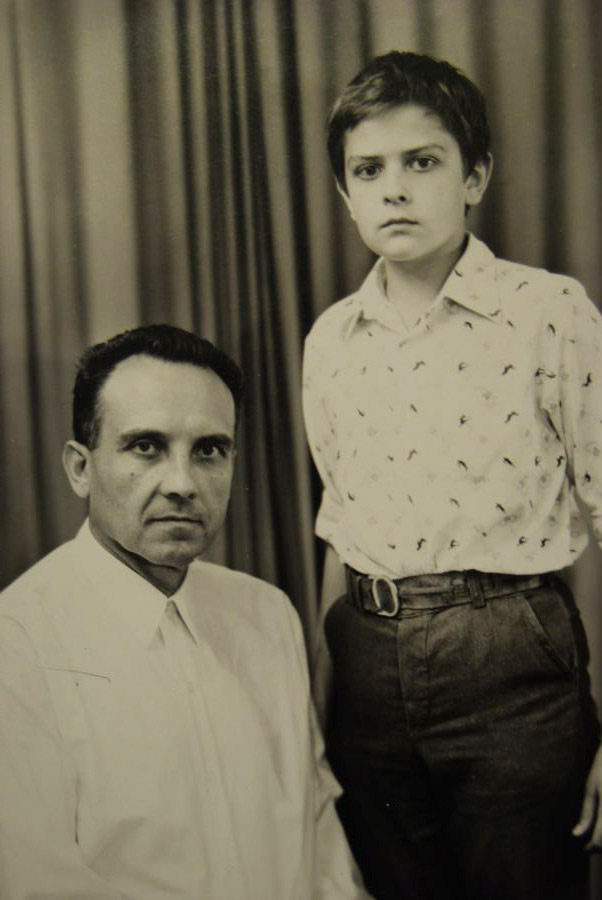

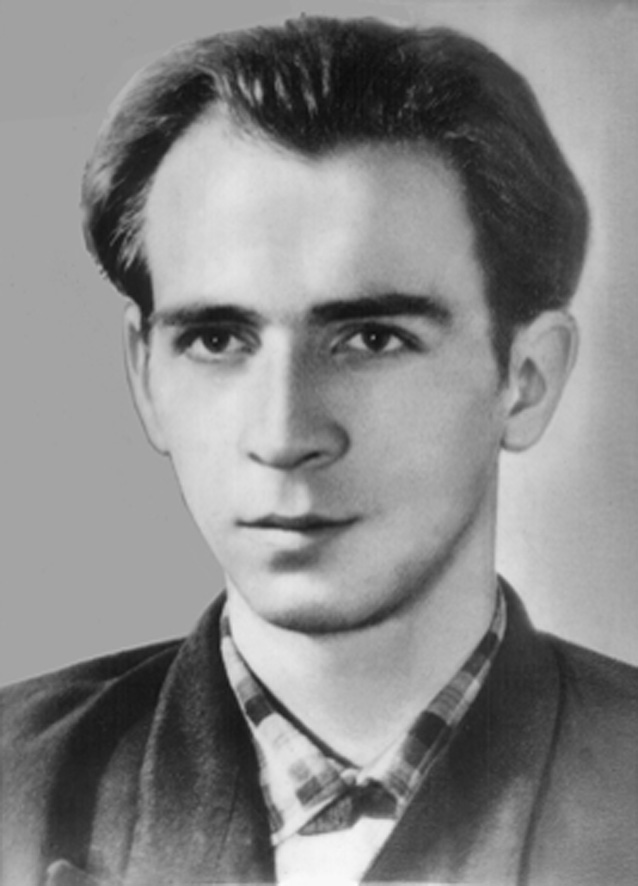

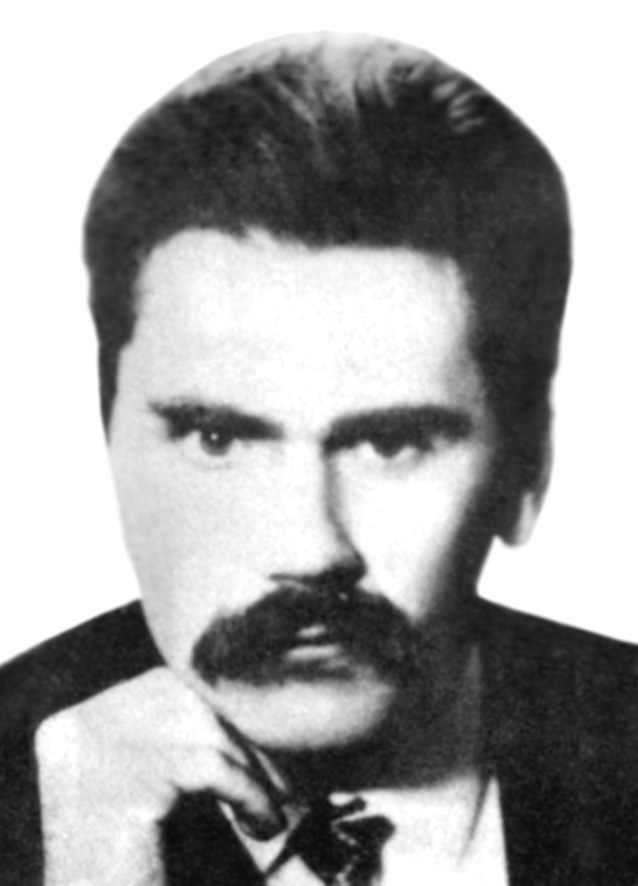

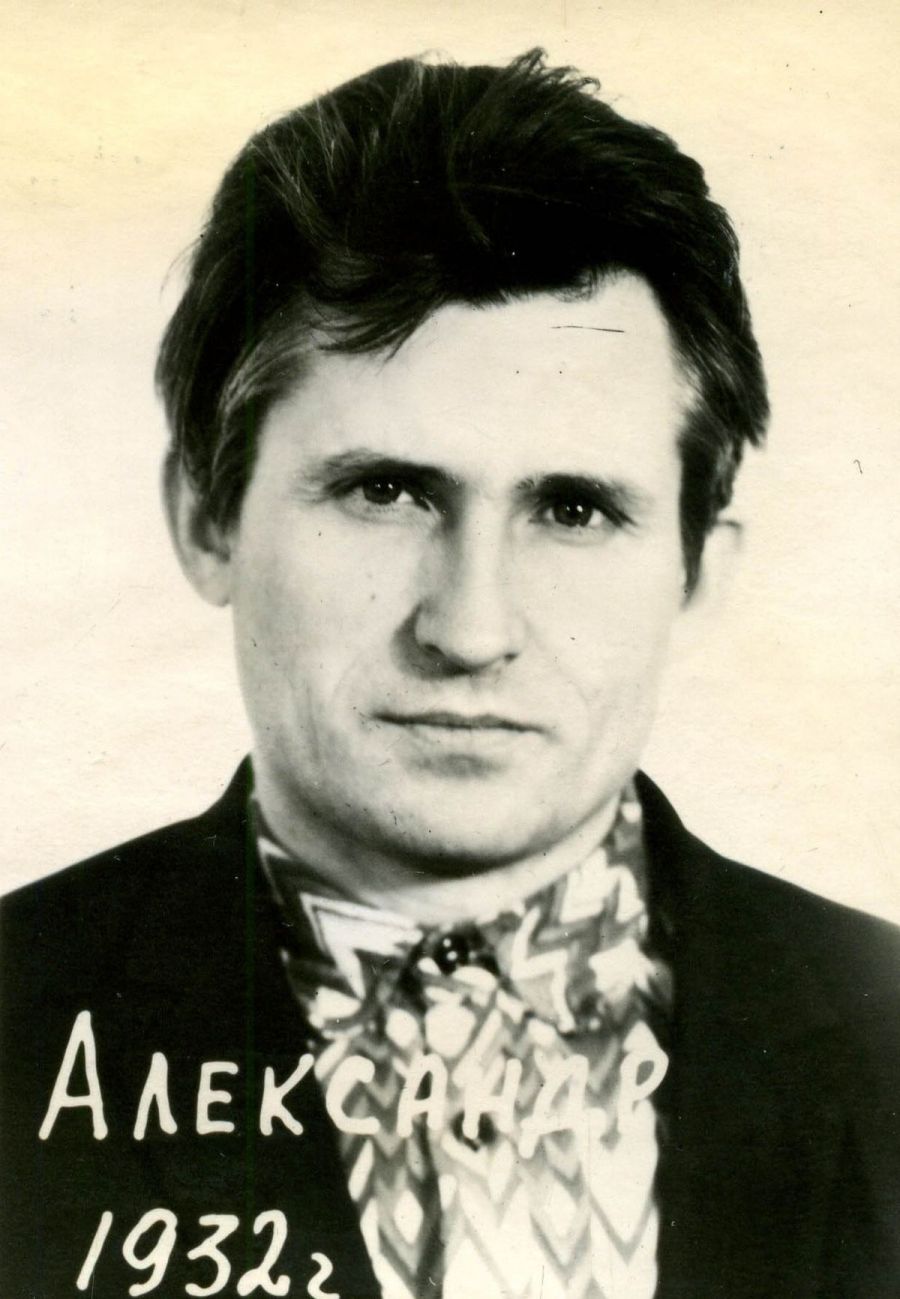

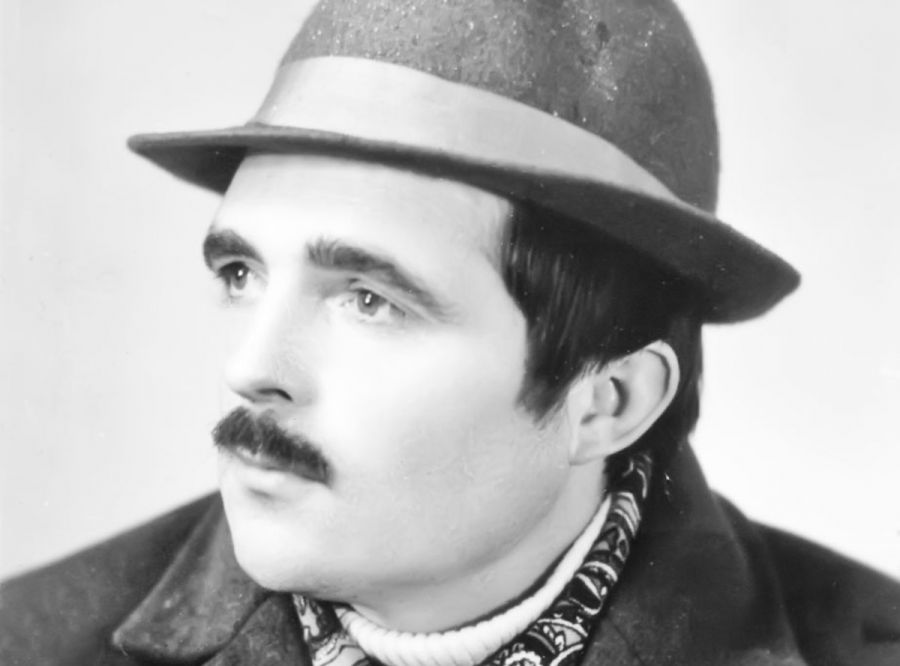

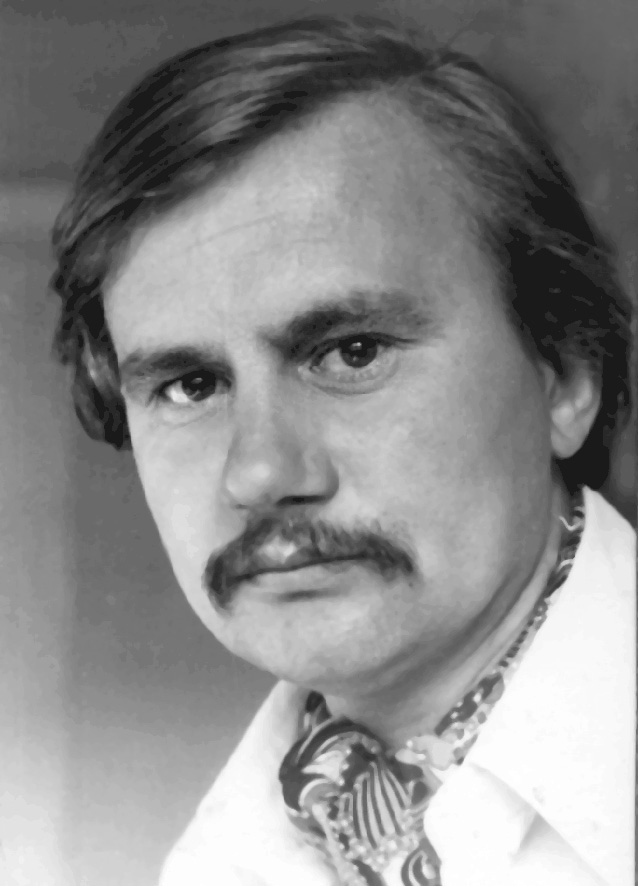

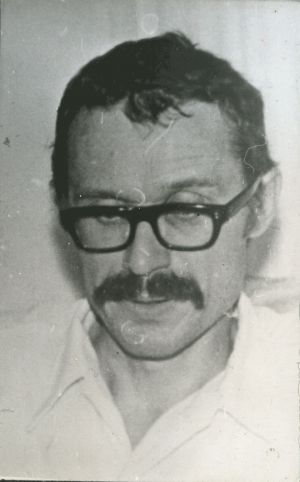

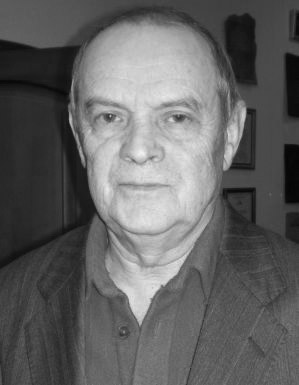

Photographs from the archive of the Kharkiv Human Rights Group, biographies of most of the people mentioned here and interviews with them can be found on this website.

[1] Касьянов Г. Незгодні: українська інтелігенція в русі опору 1960-1980-х років. – К.: Либідь, 1995. – С. 117.

[2] Захаров Є. Дисидентський рух в Україні (1954–1987) https://museum.khpg.org/1256737855

[3] Аудіоінтерв’ю з В. Овсієнком. – Взяте Б. Захаровим, 1997 // Архів ХПГ. – С. 5.

[4] Касьянов Г. Цит. праця. – С. 121.

[5] Аудіоінтерв’ю з В. Овсієнком. – Взяте Б. Захаровим, 1997 // Архів ХПГ. – С. 5.

[6] Аудіоінтерв’ю з М. Коцюбинською. – Взяте Є. Захаровим, 1997 // Архів ХПГ. – С. 6.

[7] ХТС, вып. 28. – Нью-Йорк: «Хроника», 1974. – С. 18-24.

[8] Алексеева Л. История инакомыслия в СССР. Новейший период. – М.: ЗАО РИЦ «Зацепа», 2001. – С. 25.

[9] Там само. – С. 24.

[10] Аудіоінтерв’ю з М. Горбалем. – Взяте В. Овсієнком, 1998 // Архів ХПГ. – С. 12-13.

[11] Аудіоінтерв’ю з І. Калинцем. – Взяте Б. Захаровим, 1997 // Архів ХПГ. – С. 8.