We have already written that among the key figures of the Sixtiers movement, the investigation managed to force only Ivan Dziuba to admit his guilt and recant. On March 11–16, 1973, the Kyiv Oblast Court heard his case and sentenced him under Article 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to 5 years in labor camps and 5 years in exile. On April 6, the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR upheld the verdict. At the time, Dziuba had an open form of tuberculosis and cirrhosis of the lungs. In October 1973, he appealed to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the UkrSSR for a pardon. Taking into account his partial admission of guilt, on November 6, 1973, the Presidium pardoned Dziuba, and he was released. On the same day, he submitted a statement to the editorial office of the newspaper *Literaturna Ukrayina*, which was published on November 9 (the text is provided from its publication in the journal *Suchasnist*, 1974, no. 1, pp. 82-84).

In this statement, Ivan Dziuba admits to a “profoundly mistaken understanding of a number of national problems and of the international nature of our socialist society” in his work *Internationalism or Russification?* and, in particular, writes: “I realized that I had harmed the ideological interests of my society. It is painful for me to acknowledge this, because our socialist country is dear to me. Therefore, I came to a decision that sums up my entire internal evolution of recent years: to unequivocally condemn my mistakes, to put a final and permanent end to the falsehoods of my past. It was not a matter of this or that measure of punishment, but of something much greater, a choice for a lifetime: whether to accept the brand of an enemy of my socialist society, of my Soviet people, and to surrender myself, my past and my future, to the mercy of its enemies—or not to allow this, to affirm by my deeds my right to be called a Soviet person, to atone, at least in part, for the damage I have caused.” And further: “That ‘Ivan Dziuba,’ who allowed himself to be made a byword and who wasted years of his life on political wild-goose chases, is no more and will be no more. There is a man who is pained by the awareness of his unfortunate mistakes and wasted time and who wants one thing and thinks of one thing: to work and work, to at least somewhat make up for what was lost and to overcome what was wrong. From all that has happened, I have drawn a conclusion: one must not forget that we live in a world of fierce class, ideological, and political struggle, where there is no ‘neutral territory,’ where one cannot be ‘a little’ for Soviet power, for the policy of the Communist Party, and ‘a little’ against. Inexorable reality will sooner or later force one to make a final choice.”

In this statement, one recognizes Ivan Dziuba’s style, and its complete sincerity is noteworthy. He writes exclusively about himself and his own convictions. He was burdened by the role of leader and ideologist of the national-democratic movement that the Ukrainian intelligentsia expected of him. He wanted only to be a man of letters and not delve into politics, but this was precisely what was expected of the author of the brilliant treatise *Internationalism or Russification?*. Moreover, he genuinely leaned toward socialist views and remains so to this day. It was this inner discomfort in Ivan Dziuba that KGB investigator Major Mykhailo Kolchyk, a talented man and a subtle psychologist according to Leonid Plyushch’s observation[1], skillfully exploited, gradually leading Ivan Mykhailovych to thoughts of admitting his mistakes and the need to atone for them (for more on this investigator, see here). In doing so, Ivan Dziuba did not provide any information that would incriminate his friends; he only confirmed data that had already been obtained from other accused individuals and witnesses. His wife, Marta Volodymyrivna, also persuaded Dziuba to cooperate with the investigation, as she was certain that with his tuberculosis he would not survive the camp, and therefore the most important thing was to get him out of custody at any cost.

Ivan Dziuba’s release and statement caused bewilderment and a very painful reaction among his friends. The KGB, which was closely monitoring the Sixtiers, reported the following to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine[2].

“The official announcement of DZIUBA’s pardon and the publication of his statement in the newspaper provoked a strong reaction from nationalist-minded individuals, for whom such a turn of events was a complete surprise, causing confusion and malicious attacks on DZIUBA, up to and including accusations of ‘betrayal.’

In particular, Kotsiubynska, upon learning of Dziuba’s statement, exclaimed: ‘Horrible! Horrible! I can’t understand how he could…! This is even more shameful than Franko!… I walk around as if poisoned, I still can’t come to terms with the fact that Ivan, so loved and respected by all of us, has fallen so low. Who could have thought that something like this could happen?… after all, DZIUBA was the first and most famous representative of the nation, known throughout the world, who embodied its honor. And he trampled on that honor, renounced the most sacred thing, began to carry out the orders of the KGB, to refute what he had previously proven.’

The nationalist-minded artist Sevruk, under investigation by the KGB, said in a conversation with a close contact that she had not expected such an ‘uncompromising’ statement from DZIUBA. She said that ‘with his health, he shouldn’t have clung to the remaining crumbs of life,’ but ‘should have fought to the end’…

The nationalist-minded artist Kushnir, V.V., a resident of Kyiv, in a meeting with a former like-minded individual, called Dziuba a ‘traitor to the interests of the Ukrainian people,’ stating that ‘it would have been better if he had died in prison.’

And there are many more such reactions in the top-secret KGB memorandum. So, for a significant portion of the Sixtiers, devotion to the struggle for national revival was more important than the life of a specific person? Something in this “it would have been better if he had died in prison” echoes the Soviet demand to kill oneself rather than be taken prisoner. Whereas, according to the Bible, mercy is higher than justice. Perhaps there can be no single, uniform rule for everyone here. Everyone was pressured to recant, but those who realized they could not live with that burden, like Ivan Svitlychny, for example, refused this way out for themselves, but did not deny it to others (for more details, see here). And the camp and exile did indeed kill Ivan Svitlychny: after a stroke in exile, he could no longer work and died young.

In the interview with Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska that we recently published, she speaks, among other things, about her painful reaction to Ivan Dziuba’s recantation, the writing of a letter to him, and how that letter was intercepted by the KGB. And in the document from the Sectoral State Archive of the SBU[3], which we publish below, the same is described from the KGB’s point of view. This and other episodes described by the KGB in its memorandum to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine eloquently show how the KGB shielded Ivan Mykhailovych from the influence of his friends, how his entire life and the lives of his friends were under the “operational control” of the KGB: telephone tapping, physical surveillance, mail interception, a host of informants, interference in private life… It also describes the reactions of Ivan Mykhailovych’s other acquaintances and friends, both those who condemned him for his recantation and those who supported his position, in particular, Viktor Platonovych Nekrasov, who said that for him it did not matter what Dziuba wrote, the main thing was that he was alive and free.

We invite you to read on!

[1] Audio interview with L. Plyushch. – Conducted by Ye. Zakharov, 1996 // KHPG Archive. – P. 19.

[2] SSA of the SBU, f. 16, op. 3, spr. 2, t. 3, pp. 301-305.

[3] SSA of the SBU, f. 16, op. 3, spr. 2, t. 9, pp. 327-348.

CASE 2 VOLUME 9

Series K

TO THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF UKRAINE

Comrade V.V. SHCHERBYTSKY

MEMORANDUM

The KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR is continuing its operational surveillance of DZIUBA’s behavior and is taking measures to further separate him from the influence of his former like-minded individuals and to discredit him in the eyes of nationalist elements. To these ends, we practice meetings of an operations officer with DZIUBA, conversations with the leadership of the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR, study the reactions and intentions of his former accomplices, and pay attention to shielding DZIUBA from their undesirable influence.

According to operational data, DZIUBA, in recorded conversations with contacts and family members, does not make any negative judgments, avoids candid conversations about his future plans, is painfully experiencing his situation and the possible condemnation from nationalist-minded individuals and former like-minded persons. At the same time, his actions do not show a desire to widely restore ties with them.

Among the main subjects of the “Blok” case who remain at liberty, the attitude toward DZIUBA remains the same; his statement of repentance is sharply condemned. However, these sentiments are not advertised in the wider circle of like-minded individuals, so that their true opinion does not become known to DZIUBA. At the same time, attempts are being made to ascertain his true intentions, and recently an active desire to influence DZIUBA in the interest of keeping him in his former nationalist positions has been recorded, counting on his possible return in the future to his former anti-Soviet activities or at least preventing the publication of the book *No Third Way*.

To this end, rumors are being spread around DZIUBA’s person, inspired by nationalist elements, about his allegedly depressed state, serious illness, etc., calculated to create the appearance that DZIUBA is “punishing” himself for a rash step.

The spread of such rumors is, to a certain extent, facilitated by DZIUBA’s own behavior after his release from punishment, as well as his creative passivity.

Not yet fully free from the influence of his former nationalist views, DZIUBA still reckons with the “moral” criteria that exist among his former like-minded individuals, shows elements of solidarity with some of them, and protects them from possible measures by the KGB.

His long-standing ideological closeness and friendship with like-minded individuals to some extent bind DZIUBA; he does not dare to make a decisive break with them. Despite giving assurances to the KGB to firmly fulfill the obligations he has undertaken, he continues to show vacillation, makes contact with his former connections, and strives to “save face” in this environment.

This line of behavior gives nationalist-minded elements reason to count on possible success in their “struggle” for DZIUBA, which they have, in essence, been waging recently.

The operational materials obtained also indicate that this “struggle” is being waged purposefully, taking into account the peculiarities of DZIUBA’s character.

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine was informed that during the operational surveillance of DZIUBA, we managed to obtain from him, in a sealed envelope, an inflammatory letter from M. KOTSIUBYNSKA, passed through intermediaries. After the operations officer named the author of this letter to DZIUBA, he became nervous, persistently trying to get it back or, at the very least, have it destroyed in his presence.

Despite receiving explanations about the inadvisability of returning the letter to him, DZIUBA continued to insist on his request, expressed intentions to prepare an official statement on this matter, made his further work on essays about the construction of the “3600” rolling mill conditional on the resolution of this issue, and even, in the form of an ultimatum, told the operations officer about a possible break in contact with the KGB.

In December 1973, DZIUBA’s apartment was visited by R. DOVHAN, known among the close contacts of M. KOTSIUBYNSKA as a nationalist-minded individual, after a private meeting with whom DZIUBA told his wife that they had had a difficult conversation.

In November-December 1973, meetings were recorded between DZIUBA and the nationalist-minded writer S. PLACHYNDA, author of the ideologically flawed novel *The Unburnt Bush*; the literary translator LUKASH, who was expelled from the Union of Writers of Ukraine and publicly declared solidarity with DZIUBA, who was serving a sentence at the time, and his nationalist views; the anti-Soviet-minded writer V. NEKRASOV; the subject of the “Blok” case LEVCHUK; and other hostile elements.

Attempts by the anti-Soviet-minded former member of the Union of Writers of Ukraine, O. BERDNYK, to meet with DZIUBA have also been recorded.

There is operational data about the intentions of other nationalist-minded individuals to meet with DZIUBA for the purpose of exerting a hostile influence on him.

During meetings with such contacts, DZIUBA, as has been established, does not always adhere to a line of behavior consistent with the spirit of his official statement in the press.

Thus, in a conversation with one of his former like-minded individuals about the reasons that prompted him to make a statement of repentance, DZIUBA spoke only about the lack of objectivity of certain provisions of his treatise *Internationalism or Russification?* and about the facts of its active use in anti-Soviet propaganda in the West. At the same time, he asserted that he “never intended to be” a politician, that his main calling is literature, and it is in this field that he “dreams of doing something for his people.” In conclusion, DZIUBA said: “If I had not admitted my guilt, I would never have been able to realize this dream.”

DZIUBA took an even less principled position during his meeting with the aforementioned writer NEKRASOV, which took place on January 3, 1974, at the latter’s apartment. As was established by operational means, during this meeting, NEKRASOV informed DZIUBA that he had written “witness testimony for ‘posterity’” about him, with which he had already acquainted some of his close friends (a stenographic record of the “testimony” is attached).

The “testimony” was read aloud by NEKRASOV. On the whole, it is a malicious, slanderous document, replete with praise for DZIUBA’s personality, who is exalted as an outstanding “fighter” for justice, etc. In particular, NEKRASOV writes: “I am not even talking about his culture and education, not talking about his talent and intellect; on this, everyone agrees: both enemies and friends. I want to talk about something else: about the amazing decency, nobility, and uncompromisingness of this man, about his fearlessness and truthfulness…”

DZIUBA’s nationalist activities, including his public speeches of an inflammatory and slanderous nature, are presented as “heroic” deeds, “patriotism,” etc. NEKRASOV expresses full support for DZIUBA’s anti-Soviet treatise *Internationalism or Russification?*, shares the author’s political views, and praises his civic “courage.”

This manuscript by NEKRASOV also contains other slanderous fabrications, including about the trial of DZIUBA, who, according to the author, supposedly refuted all the charges brought against him, but was nevertheless convicted.

In conclusion, NEKRASOV indicates that DZIUBA “does not know how to lie, does not know how to conform, but he knows how to be a ‘banner for all that is honest, pure, selfless, and principled.’”

After hearing the content of this document, DZIUBA said that he felt a sense of shame. In turn, NEKRASOV reassured DZIUBA, saying that he had done nothing shameful in his life. Regarding DZIUBA’s recantation statement in the press, NEKRASOV said the following: “Whatever letter you wrote, you did an important thing for all of us: you stayed alive. For me personally, that is more important than all the words you wrote. For me, you have remained who you were.”

According to NEKRASOV, his friends, including SAKHAROV, hold the same opinion.

In this regard, DZIUBA spoke about how he had not expected such approval of his behavior, but, on the contrary, had anticipated condemnation from NEKRASOV’s contacts. During the further conversation, DZIUBA showed restraint; no clearly negative judgments, nor any objections to NEKRASOV, were recorded on his part.

Given the developing situation around DZIUBA, the lack of consistency in his behavior toward his former like-minded individuals, as well as his persistent demands to return or destroy M. KOTSIUBYNSKA’s letter and his related statements and intentions, a decision was made to hold another prophylactic conversation with DZIUBA at the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR on January 2, 1974.

During the conversation, DZIUBA was informed that KOTSIUBYNSKA’s letter is of a politically harmful nature, contains offensive expressions directed at him, and could cause him emotional trauma. Guided by concern for his moral equilibrium, the KGB considers it undesirable for the time being to acquaint DZIUBA with this letter. In his own interest, it was deemed inadvisable to destroy the letter, since, in the event of the illegal dissemination of this text within the republic or abroad, such actions would constitute a criminal offense, and DZIUBA could find himself in the position of failing to report it, with all the ensuing consequences.

As a result of the conversation and the explanations given, DZIUBA agreed that KOTSIUBYNSKA’s letter should remain at the disposal of the KGB, but he still persistently asked that it not be used against the author.

During the conversation, DZIUBA reported that he had finished preparing an essay about the “3600” mill for possible publication in the journal *Dnipro*. Proceeding from the need to accelerate DZIUBA’s appearance in the press with such materials, which would contribute to his separation from Ukrainian nationalists, it was recommended that he prepare a shortened version of the said essay for publication in the next issue of the newspaper *Literaturna Ukrayina*. DZIUBA agreed to this and soon, taking our comments into account, prepared such an essay. In our opinion, it requires shortening and final editing by a professional journalist.

During the conversation, DZIUBA expressed regret that in the last two months, no one from the leadership of the Union of Writers of Ukraine had met with him, while his former like-minded individuals show constant interest in his person.

In response, DZIUBA was recommended, as in the previous conversation, to take the initiative himself to meet with representatives of the Union of Writers of Ukraine and tell them about his desire to get involved in literary activities.

DZIUBA’s attention was also drawn to the need for employment. Taking into account his previously expressed wishes, he was offered assistance in finding a job as a literary employee at the newspaper of the Kyiv Aviation Plant. We had studied this issue in advance. Of the several industrial enterprises in Kyiv that had vacancies in their newspaper editorial offices, the aviation plant is the most preferable in terms of the maturity of its collective and the presence of other conditions. DZIUBA’s work in this collective will limit his opportunities for contact with his former like-minded individuals and will contribute to his re-education. It should be noted that DZIUBA accepted this offer, but did not show particular interest in its speedy resolution.

Incoming operational information about the reactions of nationalist elements to DZIUBA’s statement indicates that this event continues to arouse great interest in their midst. According to a KGB source, for the convicted Ukrainian nationalists serving sentences in the Skalninsky Corrective Labor Colony in Perm Oblast, DZIUBA’s statement “was a bolt from the blue.” Shortly after its publication, STROKATOVA, SVITLYCHNA, N., and SENYK, who were convicted of anti-Soviet activities and are serving sentences in the Dubravny Corrective Labor Colony, submitted a written application to the KGB to obtain a personal meeting with DZIUBA in connection with his repentance.

According to operational data received, a number of nationalist-minded individuals from among the citizens of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic of Ukrainian origin, who had contacts with foreign OUN centers and maintain close ties with subjects of the “Blok” case, are seriously concerned about the consequences of DZIUBA’s statement.

In particular, SHISHKOVA, R., known among the contacts of M. KOTSIUBYNSKA, told our source that everyone who is interested in the “Ukrainian problem” in the CSSR has carefully studied DZIUBA’s statement, was shocked by this event, and cannot find an explanation for it. According to SHISHKOVA, “the negative impact of DZIUBA’s act on the ‘Ukrainian movement’ is hard to overestimate.”

A similar opinion was expressed by HENYK-BEREZOVSKA, a close contact of a number of subjects of the “Blok” case, who emphasized her confidence that DZIUBA’s statement was written by him personally, as his “handwriting” and style are in every line. She believes that this step by DZIUBA is “very significant,” the scale of its effect she finds difficult to even imagine.

Recently, the foreign nationalist press has also begun to pay more attention to DZIUBA’s statement, trying to create the appearance that his repentance was a forced act, made under pressure from the KGB. Assertions are being spread that any attempts by DZIUBA to refute his treatise *Internationalism or Russification?* are doomed to failure in advance, as this book has gained wide fame abroad as a “textbook for the study of modern Ukraine.”

Some leaders of foreign OUN centers have made similar comments in the nationalist press. Thus, the Munich journal *Suchasnist* for January 1974 published the full text of DZIUBA’s statement and commentary on it by one of the leaders of the ZP UHVR, M. PROKOP, under the title “The Tragedy and Triumph of Ivan Dziuba.” In this article, PROKOP presents DZIUBA as an “outstanding national hero” who “became a banner-figure, a bearer of the new, a beacon that orients the people and points the way of struggle.”

The author believes that DZIUBA was broken only through “violence,” his illness, and weakness of character. According to PROKOP, DZIUBA was cast down from the heights on which he stood, “pushed into the abyss of darkness and forced to worship the Mephistopheles of the North…” The article indicates that DZIUBA’s like-minded individuals, whom he called to the struggle, “will receive his repentance with pain,” but will not forget him as the author of *Internationalism or Russification?*, and will take this book “as a weapon in the further struggle.”

Taking into account the materials presented, the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR has developed and is implementing necessary measures of educational influence and separation of DZIUBA from the nationalist environment, as well as creating the appearance of his close contacts with the KGB.

In our opinion, the successful resolution of these tasks will largely depend on the publication in *Literaturna Ukrayina* and the journal *Dnipro* of the essays he has prepared on the construction of the “3600” mill, as well as the publication, after revision, of DZIUBA’s book *No Third Way* or the printing of its individual parts (Introduction, the chapter “Nationalism and Nationalist Vestiges”) in the newspaper *Visti z Ukrayiny*.

For these same purposes, it is desirable to expedite DZIUBA’s employment at the newspaper of the Kyiv Aviation Plant. At the same time, through the Union of Writers of Ukraine, to provide DZIUBA with moral support in an acceptable form and to facilitate his gradual involvement in creative work.

Proposals regarding NEKRASOV will be submitted additionally.

We report this for your decision.

Attachment: as per the text on 12 sheets.

CHAIRMAN OF THE COMMITTEE FOR STATE SECURITY UNDER THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS OF THE UKRAINIAN SSR

V. FEDORCHUK

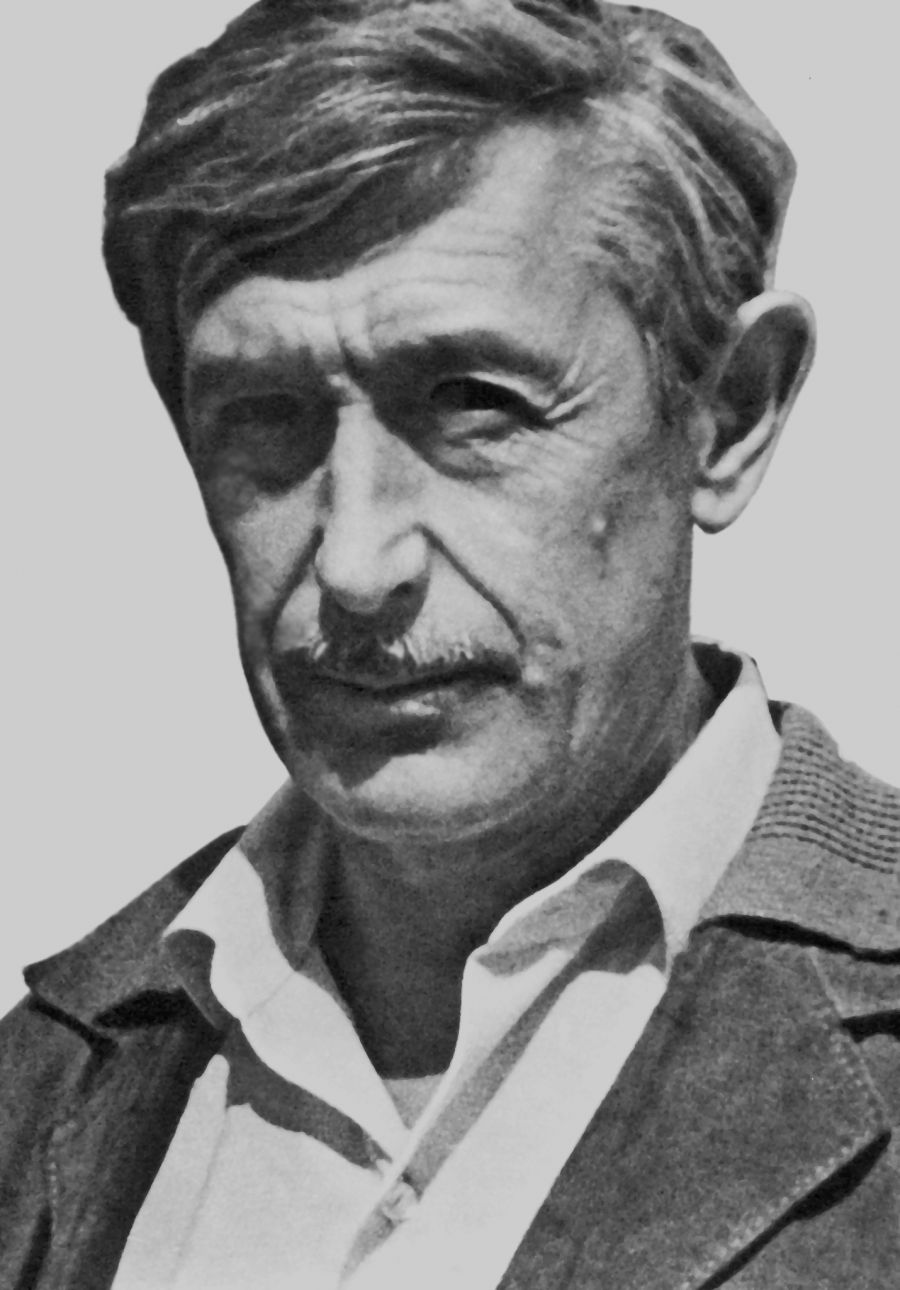

VIKTOR NEKRASOV

I did not know Ivan Dziuba during the period of his rise, his fame. I had heard of him as a talented, very educated man who respected no persons. I had not read his critical articles. Contemporary Ukrainian literature, to which his work is mainly devoted, was somehow distant from me.

Where and when we first met—I find it hard to say. The first impression, purely external. Someone pointed him out to me in a bookstore: tall, stately, in glasses, very serious, leafing through some book. Perhaps that was when we first said hello.

Then there was the episode at the “Ukraina” cinema during the premiere of Parajanov’s film “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.” This episode, not entirely ordinary in our lives, drew attention to him as a man for whom, it turns out, not only literature was dear. I was not at the premiere myself, but the next day the whole city was talking about Dziuba’s bold speech, or, in the parlance of the leaders of the Writers’ Union, his “brazen stunt.”

Disrupting the stately order of the premiere, he announced from the stage for all to hear that this great and joyful holiday (he liked the film very much) was marred by the arrests of representatives of the Ukrainian intelligentsia that had taken place in recent days. A scandal! Such things are not done here. It goes without saying that after this, Dziuba’s literary activity underwent some changes.

He had to leave the journal *Vitchyzna*, where he was head of the criticism department. He was not deprived of work as such; he became an editor first at some biological journal, then at the “Dnipro” publishing house, but they stopped publishing him; as a critic, he was struck from Ukrainian literature.

Somewhere between his speech and the beginning of his editorial work, Dziuba spent some time in the hospital, undergoing treatment for tuberculosis. It was during this period that our actual acquaintance occurred. It happened in the large hall of the October Palace of Culture at a city-wide meeting of the intelligentsia in the summer of 1963. I no longer recall what the agenda was, but the main thrust was directed against me. To use the newspaper language of those days, I was subjected to harsh criticism at various meetings and in the press. Khrushchev had publicly criticized me for my foreign essays “On Both Sides of the Ocean” and expressed doubt as to the appropriateness of my remaining in the Party. This meeting of the intelligentsia was the next step in the process of working me over. It was slightly delayed in starting. They said they were waiting for Korniychuk, who had specially arrived from Moscow just that day. When he appeared, the presidium, in a very broad composition, took its seats, and Korniychuk, as chairman, declared the meeting open. After that, everything proceeded as usual. I tried to explain something. They interrupted me, demanding that I not “equivocate,” but say directly how I felt about Comrade Khrushchev’s criticism. I again tried to explain something. They interrupted me again. It ended with me, not having satisfied the meeting, as was later written in the newspapers, stepping down from the rostrum, though, to my complete surprise, to applause.

Then Dziuba spoke, one or two speakers after me. Ascending the rostrum, he surveyed the entire presidium with a careful, cold, and calm gaze, and began to speak. I had never seen or heard anything like it. But I seem to remember that my story served him as a starting point, a springboard for reminding those present of some details of the creative biography of each member of the presidium. And in the presidium sat all the top brass.

Without hurrying, without raising his voice, without overusing emotions, and without using a single insulting or simply offensive epithet, mainly quoting from recent years’ newspapers and magazines the statements of each of those sitting at the long presidium table, he methodically, with the most elegant techniques, pinned them all, one by one, to the mat. Korniychuk, who did not escape this fate, tried to resort to his tried-and-true method—interrupting the speaker. It had no effect on Dziuba. Korniychuk turned pale, then flushed with blood, began to tap his pencil, then a glass stopper against the carafe. Nothing helped. Dziuba, having started from the left flank, was already approaching the end of the right. Then Korniychuk could not stand it, jumped up, and stripped Dziuba of the floor. He continued his execution, just pulling the microphone closer. And then I saw for the first time a flustered Korniychuk. Choking on his saliva, he suddenly yelled at the whole hall:

“Should I call the police?! Someone make a call!”

Dziuba, without batting an eye, brought his thought to its conclusion. He neatly folded his papers and descended from the rostrum. Accompanied by applause, he, without quickening his pace, walked down the aisle, left the hall, and took a trolleybus back to the hospital, where he may have even received a reprimand for being absent without leave, though I doubt it. Except for the Writers’ Union, he enjoys only love and respect everywhere.

From then on, we began to meet. Not often, not for long, not visiting each other’s homes, but feeling for each other, at least on my part, a growing attraction. I was drawn to him by a rare combination in one person of qualities infinitely dear to my heart. I am not even talking about his culture and education, not talking about his talent and intellect: on this, everyone agrees—both enemies and friends. I want to talk about something else: about the amazing decency, nobility, and uncompromisingness of this man, about his fearlessness, his truthfulness. And at the same time, a striking gentleness and delicacy, the latter, alas, now encountered less and less, especially in people not bypassed by fame. And all this with a complete absence of egocentrism and categorical, declarative pronouncements, especially in relation to people.

“You know,” he said to me right after the meeting of the presidium of the Writers’ Union where he was unanimously expelled, “I don’t even despise them. I just pity them, and in some ways, I even understand them. I read it in their eyes, not all of them of course, but the majority:

“‘Understand us! We can’t do otherwise! If we had acted differently, they would have dealt with us the same way they’re dealing with you!’

“And I don’t condemn them. I understand them.”

Of course, he both despises and condemns them, and says he pities them. Using the same root, let’s say, he finds them pitiable. But out of pity, he says that he pities them.

“After all, maybe,” he continued, “only three or four of all those gathered had not, at one time or another, shaken my hand and thanked me in the most enthusiastic terms for my letter to the Central Committee. But here, at the meeting, with one voice, they said they hadn’t read it.”

And these were, I will add, people considered to be the chosen few, who, like no one else, understand matters of ethics and morality and are endowed with the right to teach this very thing to others. These were intelligent, well-read people. People who know they are lying not only to others but also to themselves, who know that with their lies, with every word, they are bringing the one they have slandered closer to the fate they themselves mortally fear.

A little earlier I mentioned delicacy as an almost forgotten quality. And I want to begin with it, sketching a portrait of a man whose specialty is criticism, and whose calling is the struggle for truth and for an idea. By the concept of delicacy, I mean attentiveness to others, the ability to listen to the end without interrupting, the desire to understand and not just to object, never to overtake the one walking alongside. An organic hatred of rudeness in all its manifestations: whether on a tram, on the street, or somewhere else.

A tiny detail. In conversation with a Russian, Dziuba always speaks Russian, although the ever-decreasing use of the Ukrainian language in everyday life is one of his most painful wounds. In these cases, I always want to switch to Ukrainian.

For some reason, the most positive human virtues are now considered to be: energy, assertiveness, purposefulness, demandingness, firmness, diligence, the presence of organizational skills, a strong will. In the obituaries of deceased leaders, sensitivity and responsiveness also appear, it’s true. But I think that’s only in obituaries.

But such concepts as decency, nobility, tolerance, kindness, gentleness, mercy, generosity, and, well, the aforementioned delicacy, have been completely dropped from our vocabulary of positive and approved qualities. Well, in Ivan Dziuba, they are all there. It is precisely they that enrage people who are deprived of them. However, in Dziuba they are combined with principled, established character traits—purposefulness, demandingness, mainly toward himself.

Dziuba’s enemies love to call him a cunning and experienced demagogue. This is always said about people who are not so much cunning as they are intelligent, with whom it is difficult to fight using logical categories, since logic is on their side. Therefore, they are called demagogues. Dziuba is not a demagogue. He has always fought with an open visor. But truth is dearest of all. Sometimes he may even use the enemy’s weapon, though never smearing it with poison. He fences well enough to do without it. He can also offend. And offend deeply, but always deservedly.

What a rage Dziuba’s words induced in the participants of that shameful presidium meeting, when, looking them over with his calm gaze, he said:

“I am guilty only of the fact that you want to eat. And oh, how you want to eat!”

In order not to lose the contents of the feeding trough for the chosen, they are ready to choke on more than just Dziuba. And yet, sitting at that tribunal were people who truly understood what Dziuba was and what they were condemning him to. A month and a half later, they put him in prison. It is curious that some of them, I don’t want to name names, later—God forbid, not themselves, but through their wives—offered him material assistance. I have no words to describe the rage that seizes his enemies at the mere mention of his name. In all my Party affairs, they brought up Dziuba to me every time, my friendly relations with him. At the mere word “Dziuba,” my interlocutors’ faces changed. My sins were forgotten, and Dziuba’s grew to incredible proportions. The CIA, the FBI, the State Department all figured in. And the undried ink of all possible intelligence agencies. And in one of the accusations, printed, if I’m not mistaken, in the magazine *Perets*, it was simply stated that Dziuba, with his slanderous “works,” was supporting the shaky front of the puppet Thieu. Moscow simply roared with laughter when I told them.

In the conclusions of my personal case by the Party commission of the Leninsky district, it was written in black and white that I maintain contact with a saboteur and a prostitute who had inveigled his way into the Writers’ Union by deceit. I wanted to copy it down, but I’ll remember it. “What is the cause of such fury? A real hatred of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists, of whom Dziuba is considered the leader?! Or the fact that he demands the ‘secession’ of Ukraine from the Soviet Union?! The unification of Zionists with these bourgeois nationalists? Or simply a call to fight against the Communist Party by all legal and illegal means?!” Yes, this was always said, all this was said to me. At any rate, this is exactly how my Party investigator in the Leninsky district committee explained the essence of Dziuba’s letter to the Central Committee to me. Why, one asks, such an escalation of lies, such a collection of crimes pulled out of thin air! Is it really impossible to do without all these shaken thrones and undrying inks?! It turns out, it’s not. There is nothing to cover it with except lies and slander.

I read Dziuba’s letter to the First Secretary of the Central Committee of Ukraine, Shelest. This serious work, numbering no less than 200 typewritten pages, entitled *Internationalism or Russification?*, is indeed a work. A work written by a man to whom the literature, culture, and traditions of his homeland—Ukraine—are not indifferent. Yes, he loves Ukraine. He loves all things Ukrainian. He loves the language, the art, the history, he loves its landscapes, its songs, its poplars, the Dnipro, Kyiv, he loves Shevchenko and Skovoroda, and for this, he loves Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Pushkin, Marina Tsvetaeva, Akhmatova, Pasternak no less. Yes, he loves and highly values Russian culture, the Russian language!

But when, due to irreversible circumstances, the Ukrainian language begins to wither, when, in the fight against foreign influence, against Polonisms, they begin to Russify it, when Kyivan Rus begins to be called ancient Rus, when the number of Ukrainian schools in cities steadily decreases, when to this day libraries do not issue books by M. Hrushevsky, a historian of world stature, when not a single film script, be it about beetles or the dangers of drunkenness, can be put into production without Moscow’s approval, then one involuntarily wants to turn to someone, to expect an answer from someone.

And Dziuba turned to the Central Committee of the Party. A crime? It turns out, yes. True, the punishment was 5 years in a strict-regime camp after this. Seven years after the crime itself was committed. The Party leadership changed, and the methods of combating dissent changed with it.

But, if we look at what happened more broadly, the matter is by no means in the crime itself. Not even in the fact that some facts became public knowledge worldwide. Dziuba, in the end, only summarized and concretized what was already known. The matter is in Dziuba himself, in his existence. Judge for yourself. How peacefully and calmly the process of development of Ukrainian Soviet literature proceeds. The writers, it is true, as always, are in debt to our demanding readers, in particular, to the working class, the full depth of whose consciousness and achievements they cannot yet fully comprehend and analyze. But they—the writers—are on the right path. And feeling the support of that same working class and its vanguard, honing their craft year after year, they achieve more and more success.

It doesn’t matter that the thousands-strong print runs of the book about “The Man in the Star-Bearing Kremlin” and another, “Who Was With Us at the Front and in Labor,” have disappeared from the shelves and library stacks. What matters is something else. The writer is always with the people in all moments of their lives, in joy and in sorrow. And new books come from their pens and are published in the same multi-thousand-copy runs. One-, two-, and six-volume editions are reissued. And the people, supposedly, read them. And films are made based on them. And at plenums and congresses of writers, long lists of authors of “interesting, topical, ideologically oriented short stories, novellas, and novels” are read out.

And in vain do some malicious critics there talk about the writers’ detachment from life. On the contrary. They can only dream of peace. They visit miners, go down into the mines wearing helmets. On a collective farm, they are presented with bread and salt, shown the pigsties. Then the poets and prose writers read their works, and the collective farmers talk about their successes. And the border guards, and the steelworkers, the cotton growers, the fishermen, the defenders of the sea borders? Where does the writer not look? Everywhere he is welcome, everywhere they applaud. Everywhere they ask him to write about them even more and even better.

And then a Dziuba appears who, for some reason, is not thrilled by this. For some reason, he recalls that someone, sometime, informed on his fellow writer and for some reason even calls it a denunciation, puts some unknown young poets on a pedestal, asserting that they, you see, have their own voice. Their very own.

We know this, we’ve seen it before. And in general, Comrade Dziuba, you are still young to be teaching us. You’ve started swinging too early. It wouldn’t hurt you to learn a thing or two yourself, to gain some sense.

And so, instead of heeding sensible advice, of listening to his more experienced elders, Dziuba, you see, dared to prove the unprovable, to try to cast a shadow on the fence. And to put it bluntly, to slander the most sacred thing—the policy of the Party. With unclean hands, wielding some statistical data, juggling articles of the Constitution and cherry-picked quotes from Lenin, he tried, clearly pouring water on the enemy’s mill, to blacken our national policy, the clarity and consistency of which are known to the whole world. His, forgive the expression, “work,” or more simply—a slanderous opus, odiously titled *Internationalism or Russification?*, is obsequiously placed by him on the table of the most inveterate enemies of the Soviet Union, the surviving Petliurites and Banderites, and they just rub their hands together.

I made up the entire tirade above, but I ask you to believe me: it is but a faint reflection of what was written and repeated from the rostrum or in confidential conversations about Dziuba. In a word, “so that he wouldn’t be so clever.”

To my great regret, I was unable to get into Dziuba’s trial. Our so-called open trials—and the trial was open—are distinguished by the fact that the tiny rooms in which they are held turn out to be already overcrowded before the doors even open. And anyway, where are you going? But I know what happened there. Even Dziuba’s enemies—and a place was found for them—were forced to admit that he behaved with such dignity, spoke so convincingly, that it seemed as if the court was about to release him from custody and see him off with applause. That did not happen, but the verdict, they say, was heard in dead silence, and those present (and what a presence it was?) then dispersed, not looking each other in the eye.

It is curious that not a single one of the witnesses—and they were selected by the prosecution with more than strictness—dared to say a single bad word about the defendant. They only confirmed, which Dziuba did not deny, that he had given them his manuscript to read. This fact was assessed by the court as the fact of disseminating the manuscript.

Not one of them called him a nationalist, or a slanderer, much less an anti-Soviet or an enemy.

A touching detail. One of the witnesses, a young, aspiring writer, was asked: “Did Dziuba express any anti-Soviet thoughts in his presence?” “What are you talking about!” the young man replied indignantly. “On the contrary. When I once told Ivan Mykhailovych that I was planning to do something not very approved of, he tried with all his might to convince me not to do it.”

Here Dziuba took the floor. It must be said that he was not once interrupted during the trial, and in general it proceeded with the utmost correctness. He tried with all his might to convince the court that the young poet was not planning to do anything forbidden. That he was exaggerating all this, mistaken, or had simply forgotten.

After the trial ended, rumors, clearly inspired, reached me that at the trial, Dziuba had supposedly admitted everything and even expressed gratitude to the investigative bodies. This is all nonsense. What could he have admitted? That he wrote an anti-Soviet, slanderous piece, that he sent it to Shelest for cover, but was actually writing for Canadian nationalists? Or that he had twisted Lenin, falsified all the data? No. At the trial, he said directly that what he had written was not a scholarly work, but an emotional piece, to some extent provoked by the wave of arrests among the Ukrainian intelligentsia. And we had grown unaccustomed to that. He said just that at the trial, that the selection of negative phenomena in his work was done completely consciously, something he would never have allowed himself if he were writing for a wide readership. But here he was appealing to the highest possible authority, wishing to draw attention precisely to the negative, to distortions and excesses.

He also spoke of the fact that, if he were to sit down to write this letter now, he might perhaps write it differently. Any writer or critic, concerning their work, always or almost always says just that. As for the gratitude he expressed to the investigative bodies, yes, he did indeed say that he was grateful to the investigation for providing him with special literature, which gave him the opportunity to refute all the accusations brought against him concerning the allegedly anti-Soviet platform he had written.

As a result, he managed to refute all the accusations of an expert examination that proved to be subpar. That is how things really stood, which, however, did not prevent the court from delivering its verdict—5 years of strict regime.

Dziuba’s enemies—and they are all mainly in the leadership of the Union—now very much want to portray him as malicious, bloodthirsty, ungrateful. The Soviet government gave him, a man from a simple Donbas family, an education, made him a cultured person, and he, you see, instead of gratitude, slings mud at it. He was entrusted with a most important section of our literature—criticism, and he, using his position as head of the criticism department of the most respectable journal, *Vitchyzna*, began to settle personal scores, not shying away from any methods. He was repeatedly warned, they had friendly, consultative conversations with him: he wouldn’t even listen, he went on the counterattack. And all his talent and intellect—this cannot be denied him—instead of giving to the Motherland, he gave to the enemies. He became a banner for all those who hate with a fierce hatred all that is advanced and progressive, who slander their Motherland, not wanting to see all the beautiful things of which it is justly proud.

Perhaps it is difficult, or rather, useless to explain to these people that there are people for whom something is dearer than the positions they hold, that there is such a feeling as pain, and such a concept as conscience, that for a certain category of people the word “duty” is not just a combination of consonants and vowels, but something more. He is sure that a person who dares to openly criticize anything, first of all, risks his well-being, if not his head. It cannot be explained. I tried. It’s useless. It’s useless because those on whom the fate of a man whose place is in the front ranks of Ukrainian culture depends, understand everything perfectly well.

And, being fully aware of everything, they, at best, silently raised their hands for the next decision that appeared after this one. “For the production and dissemination of deliberately slanderous and anti-Soviet materials, used by our enemies against the Soviet Union and the Communist Party, Dziuba, I.M., is to be expelled from the Union of Writers of Ukraine.”

Not a single vote against, not a single abstention, not one of these people, these writers, each of whom had probably written in their books about courage and valor, steadfastness and principle, found in himself even a hundredth part of these qualities to stand up and say:

“Come to your senses!! What are you doing!!! Remember the fate of Rylsky, Sosyura, Yanovsky. You yourselves will be ashamed!!”

No, such a person was not found. And no one will be ashamed. There is no shame. It has been forgotten. When Dziuba spoke at Babyn Yar on the 25th anniversary of the massacre, many cried. I myself had difficulty holding back tears. They cried because a man was speaking about the feeling of shame he experiences, seeing that the enmity and mistrust of one people toward another—Ukrainian toward Jewish, Jewish toward Ukrainian—have not yet been fully eradicated. He spoke of this with pain and did not hide his shame. This is how an honest man acts. This truth, however, did not in the least prevent a dishonest person from later saying:

“He called at Babyn Yar for nationalists to unite with Zionists against the Soviet Union.”

I don’t know, maybe there is another Ivan Dziuba, with Petliurite tridents tattooed on his chest, in an embroidered shirt, in Zaporozhian trousers, with a “yellow-and-blue banner” in one hand and a sawed-off shotgun in the other. I saw something similar in that same magazine, *Perets*.

But the one I know and love is different. He is gentle and tender. It’s enough to see him next to his little daughter. Or when he presented his sick mother with the obligatory bouquet of lilies of the valley—and at the same time he is firm and unbending in his convictions, though attentive and responsive. Once, in difficult times for me, I found an envelope in my mailbox with a small sum of money, “more, unfortunately, I don’t have right now.”

At the same time, he knows how to strike a mortal blow. His blows are accurate and the wounds do not heal. He, as they say, wouldn’t hurt a fly, even the guards said of him: “A holy man.” But he will humiliate a scoundrel without any pity and trample him into the mud. How many more await such a fate. I wait—I can’t wait.

He does not know how to lie, he does not know how to conform, he does not know how to threaten. No, he will never sit in a big office, with a big desk and multicolored telephones. He is not fit for that. But a banner—forgive the word—he can be. A banner for all that is honest, pure, selfless, and principled.