Memorial has undertaken a special study to calculate the number of victims. The calculations are based on figures extracted from the official reports of punitive agencies. An analysis of the documents studied convinces us that, on the whole, the figures presented in these reports can be trusted. Based on the types of repression and the types of sources we rely on, the calculations are divided into two parts:

▪ the scale of repression “on an individual basis”

▪ the scale of administrative repression

Repression “on an individual basis” was almost always accompanied by the observance (even if only on paper) of investigative and (quasi-)judicial procedures. A separate investigative file was opened for each person arrested. Statistical records for such cases were kept systematically by state security agencies in a uniform (though periodically changing) format.

Administrative repression is repression without individual charges, applied, in most cases, on the basis of formal group characteristics (social, national, confessional, etc.). The usual punishment was the confiscation of property and forced resettlement to “remote regions” of the country, as a rule, in specially created “labor settlements.” Statistical reports are found in the files of various state departments; they were kept in connection with individual campaigns and are significantly less complete and accurate than the reports on “individual” repression. Personal files on the deportees were opened not at their place of permanent residence but only after their arrival at the place of punishment; no files were created at all for those who died en route.

1. Political Repression “on an Individual Basis”

The source for the study of repression “on an individual basis” is the reports of the Cheka-OGPU-NKVD-KGB. They have been preserved in the archive of the current FSB in a relatively complete state, beginning in 1921. We had the opportunity to study the reports for the years 1921–1953. To obtain data on the repressions of 1918–1920 and 1954–1958, we use figures from the works of V. V. Luneev.

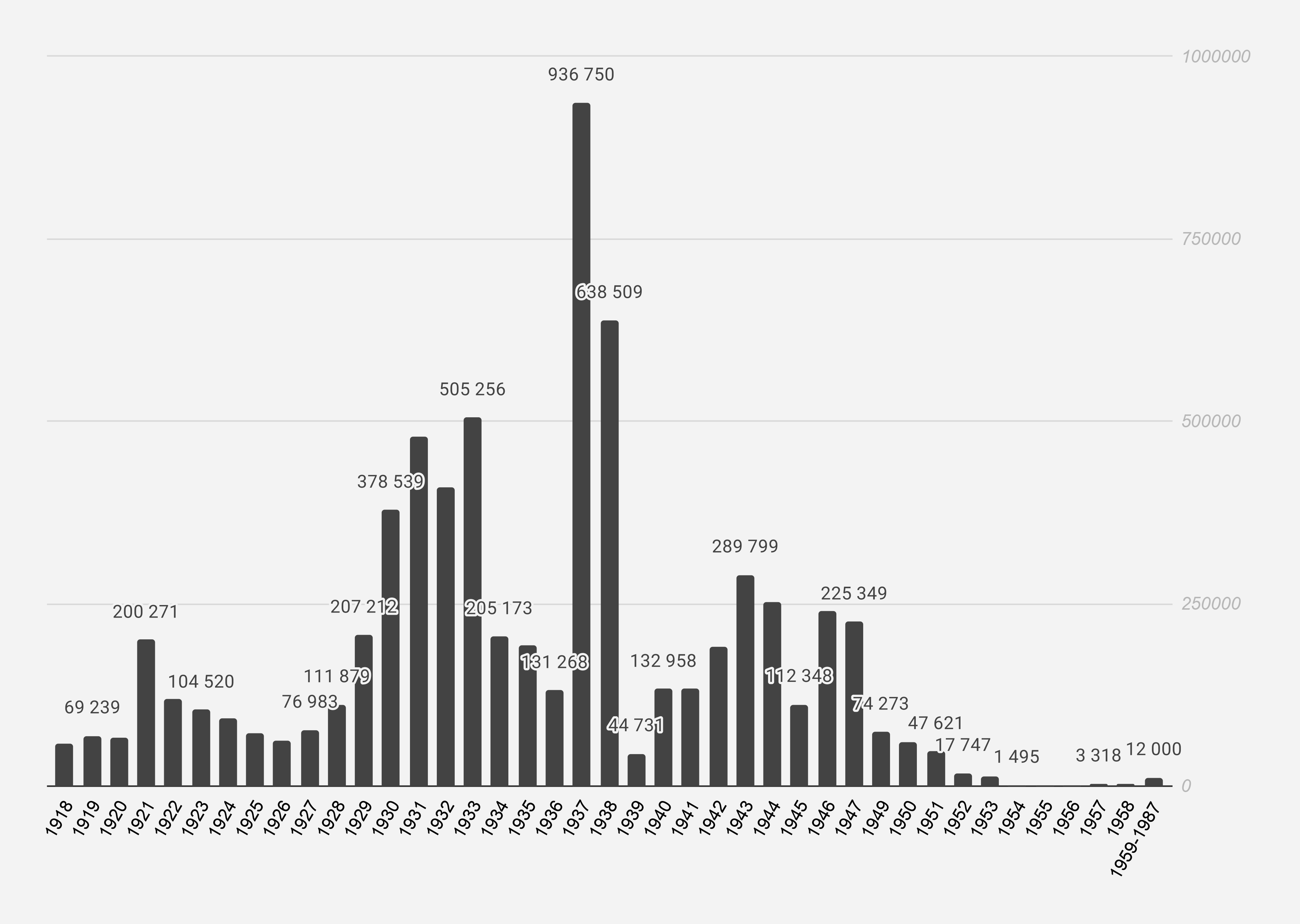

Arrests by the Cheka-OGPU-NKVD-MGB-KGB “on an individual basis,” 1918–1987.

Of course, these data are not entirely complete—for example, we are convinced that the number of victims from 1918–1920 was greater than what is indicated in the table. The same applies to the period 1937–1938, as well as 1941. However, we cannot provide any more precise, documentarily confirmed figures.

In total, we see that state security agencies arrested about 7 million people over the entire period of their existence.

At the same time, the statistical reports allow us to determine how many people were arrested each year and on what charges. Studying the figures from this perspective, we see that the special services arrested people not only on political charges, but also on charges of smuggling, speculation, theft of socialist property, malfeasance in office, murder, counterfeiting, etc. To truly determine the presence or absence of a political motive in each specific case, one would need to study the individual case files. This is practically impossible. We are forced to deal not with specific cases, but with figures in reports.

An analysis of the reports leads to the conclusion that “non-political” cases make up at least 23–25% of the total number of those arrested. Thus, we should be speaking not of 7 million victims of Soviet political terror, but of approximately 5.1–5.3 million.

However, this figure is also inaccurate, as the reports reflect not named individuals, but “statistical units.” The same person could have been arrested several times. For example, during the first two decades of Soviet power, members of pre-revolutionary political parties were arrested four or five times, and representatives of the clergy were arrested several times; many peasants first arrested in 1930–1933 were arrested a second time in 1937, and many of those released after 10-year sentences in 1947 were soon arrested again, etc. The statistical reports do not provide exact figures on this, but we estimate that there were at least 300,000–400,000 such people. Thus, the total number of people subjected to political repression on individual charges is, apparently, 4.7–5 million people.

Of these, according to our calculations, 1.0–1.1 million people were executed by verdicts of various extrajudicial and judicial bodies; the rest were sent to camps and colonies, and a small portion into exile.

Looking ahead, let us consider this figure from the perspective of the rehabilitation process of the 1950s–2000s. Of course, not all of those repressed for political reasons were subject to rehabilitation—among them were actual criminals (for example, Nazi war criminals or Soviet citizens who served in Nazi punitive squads)—but it is beyond doubt that:

▪ the overwhelming majority of these approximately 5 million people were innocent victims of the regime;

▪ each of the cases against these people should have been reviewed by the prosecutor's office and the courts for rehabilitation, and for each case, a detailed, well-founded answer should have been given as to whether the person was subject to rehabilitation or not.

2. Political Repression via “Administrative Measures”

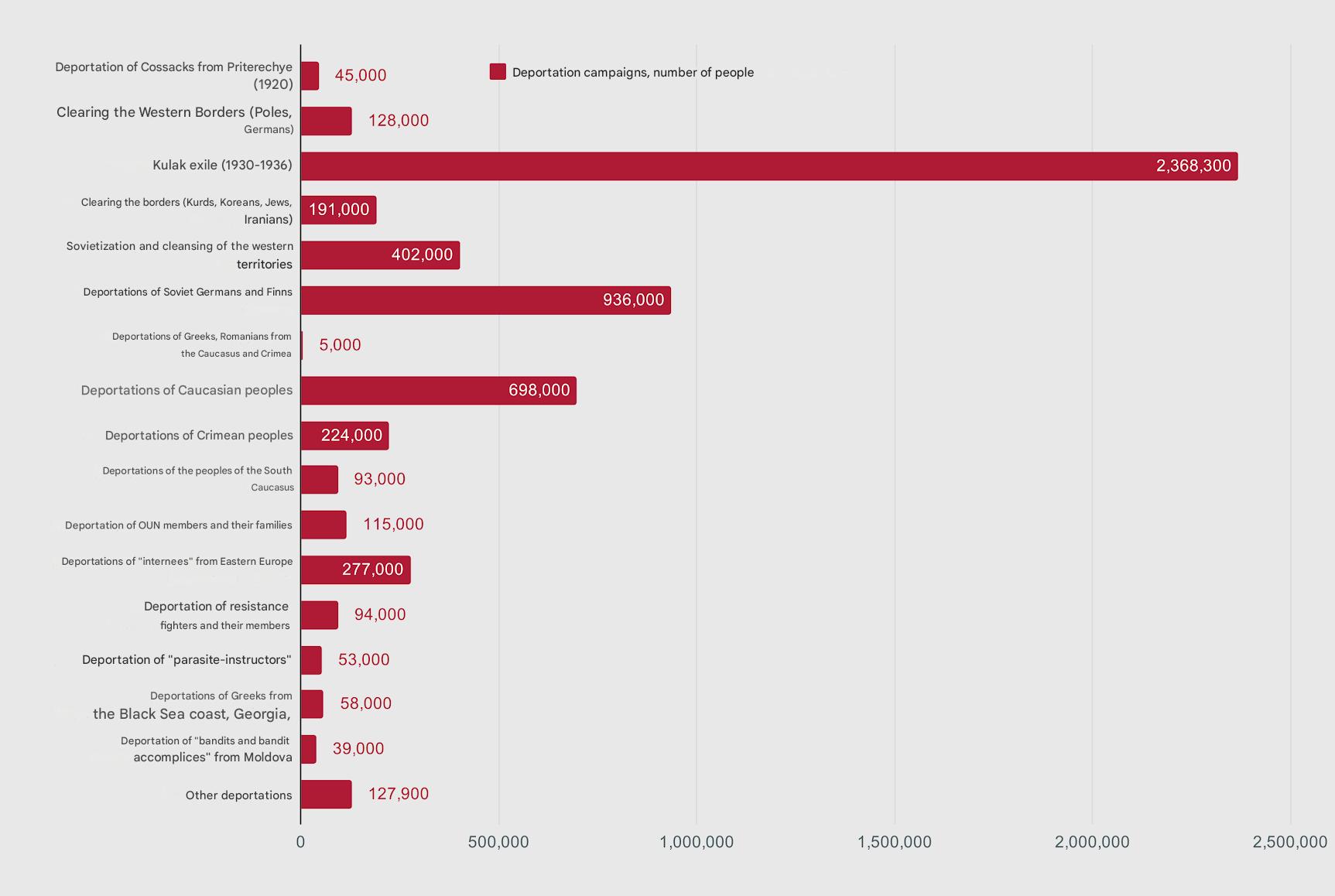

Administrative repression was carried out by decisions of a wide variety of bodies: Party, Soviet, and state. The documents allow us to identify the main repressive campaigns (or “flows”) with the approximate (more or less accurate) number of victims for each. Unlike individual repression, we can consider all victims of these repressions (deportations) to be victims for political reasons—this motive is explicitly stated in almost all state decisions regarding each specific campaign.

The most massive deportations were the exile of peasants during the era of “collectivization” (1930–1933), the deportation of “socially dangerous” Poles and Polish citizens, as well as citizens of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Moldova after the forced incorporation of Eastern Poland, the Baltics, and Bessarabia into the USSR (1940–1941), the preventive deportations of Soviet Germans and Finns (1941–1942) after the start of the Soviet-German War, and the total deportations (1943–1944) of the “punished peoples” of the North Caucasus and Crimea (Karachays, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Crimean Tatars, and others).

In determining the number of deportees, Memorial relies on contemporary research, in which we have partly participated.

Deportation campaigns, 1920s–1950s. According to research by Pavel Polian et al.

Due to the lack of precise figures, the above list omits a whole series of victims of administrative repression: those who were “dekulakized” without being exiled (i.e., stripped of their homes and property and resettled within their own regions) during collectivization; former Soviet prisoners of war who, after “filtration,” were forcibly sent to “labor battalions” after the war; and a whole series of other, numerically less significant flows (the 1921 exile of Kulak-Cossacks from the Semirechensk, Syr-Darya, Fergana, and Samarkand oblasts beyond the Turkestan Krai, particularly to the European part of Russia; the 1942 deportation of Germans, Ingrian Finns, and other “socially dangerous” elements from the border districts of the Leningrad Oblast; the 1948 deportation of Crimean Tatars and Greeks from the Krasnodar and Stavropol Krais, and many others). Also not counted here are children born in exile who remained with their parents in special settlements. In total, according to various estimates, there were at least 6 million victims of deportation (most likely 6.3–6.7 million).

In total, approximately 11–11.5 million people were repressed for political reasons across the entire USSR. The question of rehabilitation should have been decided for this number of people.