A new page has appeared in the history of Ukrainian resistance to the Soviet regime in the Donetsk region. It is connected with the fates of a student from Kramatorsk, Hanna Yurchenko, and the teacher from Druzhkivka, Oleksa Tykhyi. And it began like this.

In the autumn of 1956, an armed uprising against the local communist government broke out in Budapest. Hungary was then part of the so-called “socialist bloc,” so Soviet troops were sent in almost immediately to suppress the rebellion. This event caused outrage not only in Europe, undermining the USSR’s reputation among Western supporters of communism, including, for example, the famous philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, but also within the Soviet country itself.

Taught by the experience of past decades, the population of the Ukrainian SSR prepared for another war. In the cities of the Stalino (Donetsk) Oblast, people bought up salt, sugar, soap, kerosene, and matches en masse. All sorts of rumors spread among the people. There were many voices supporting the actions of the rebels. However, only a few spoke out openly. Among them was a circle of students from the Kramatorsk Industrial Institute and a village teacher, who would later become a Ukrainian dissident—Oleksa Tykhyi.

It is unknown whether they acted in a coordinated manner. In any case, several students likely signed a petition against the deployment of troops to Hungary. In parallel, O. Tykhyi wrote a letter of protest to the Central Committee of the CPSU, stating that the Magyars should decide their own fate without outside interference.

Events developed quite rapidly thereafter. Hanna Yurchenko, a first-year student in the correspondence department, was arrested. Around the same time, O. Tykhyi, the head of studies at the evening school in the village of Oleksiievo-Druzhkivka, was also arrested. While some fragmentary data about Tykhyi’s trial have been preserved, almost nothing is known about Yurchenko’s case. Why Hanna in particular was arrested, and whether anyone else was involved in this case, is yet to be clarified by researchers. Hanna’s younger sister, Olena, recalls that someone scattered leaflets with the slogan “Freedom for Hanna Yurchenko!” near the personnel department of the Novokramatorsk Machine-Building Plant (NKMZ). It is rumored that these were Hanna’s friends from the institute. Soon, closed trials were held in Stalino (Donetsk). Hanzia, as her friends called her, who suffered from a heart defect, received a four-year prison sentence, while Oleksa received seven years in the camps and five years’ deprivation of civil rights.

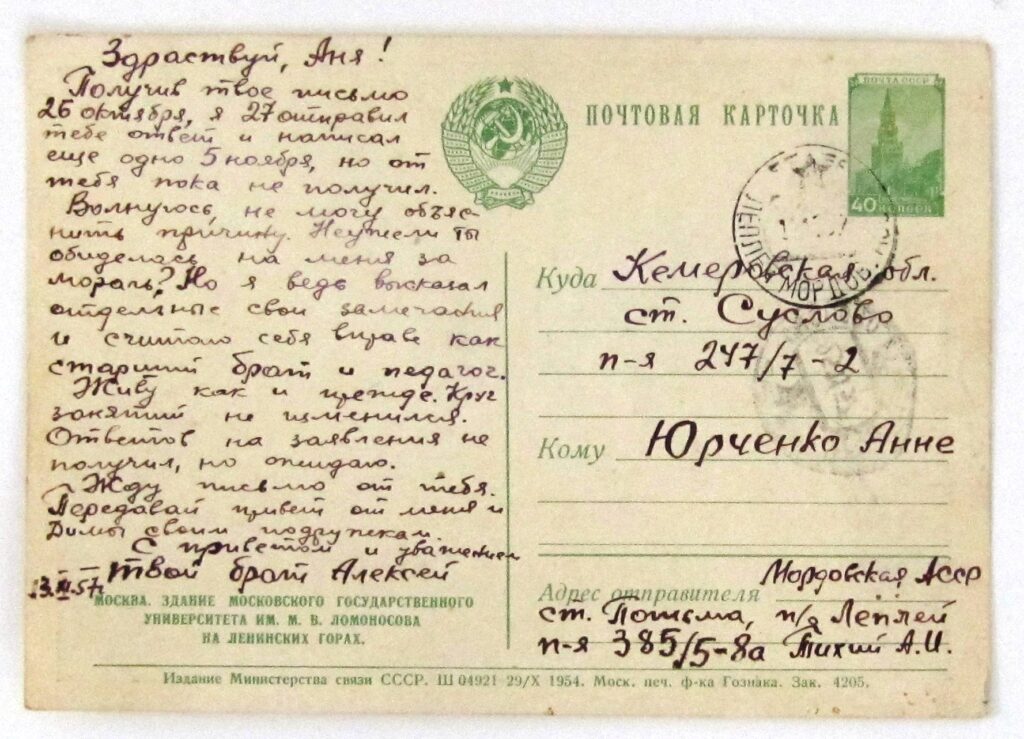

The front of the postcard written by O. Tykhyi to H. Yurchenko. From the collection of the Donetsk Regional Museum of Local Lore (DOKM)

The back of the postcard, DOKM

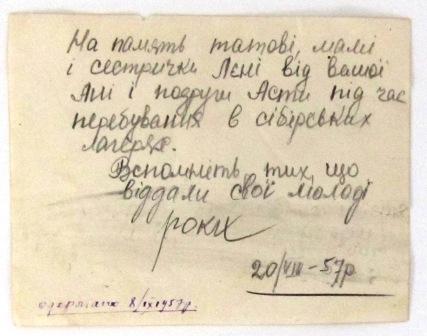

It is still not known for certain whether they communicated before their imprisonment or perhaps met at a transit prison, but a small correspondence between the prisoners Tykhyi and Yurchenko has been preserved, including a telegram and a postcard. Tykhyi wrote from the Mordovian camp in Potma to the Siberian one—in Suslovo. This was a difficult time of adaptation in the camps (the postcard is dated November 13, 1957), so Tykhyi tried to support Hanna, corresponding with her more or less regularly. Meanwhile, she had already befriended an Estonian woman, Asta; the girls supported each other and even stayed in touch for some time after their imprisonment.

In the photo, Asta (left) and Hanna (right) in Siberian camps, 1957, DOKM

The back of the photograph, DOKM

Tykhyi almost immediately plunged into organizing a camp uprising, for which he received an additional punishment in the form of a year’s detention in the strict-regime Vladimir Prison. In the Mordovian camps, he met many interesting people and became definitively committed to the Ukrainian cause. And towards the end of his term, he became acquainted with Levko Lukianenko, with whom they became true brothers-in-arms.

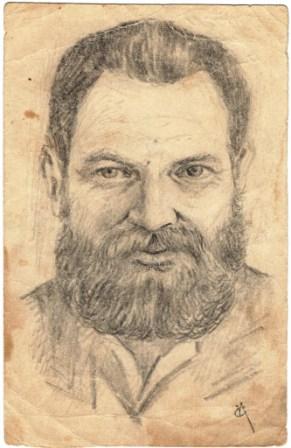

O. Tykhyi, January 1958, a drawing from the collection of the Druzhkivka Historical and Art Museum

After their release, both Hanna Yurchenko and Oleksa Tykhyi were constantly under the surveillance of the KGB. Tykhyi continued to resist the system, eventually joining the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, for which he and Mykola Rudenko were tried in Druzhkivka in the summer of 1977. After this, Tykhyi did not return alive, dying in 1984 in a prison hospital. The system killed him, but it did not break him.

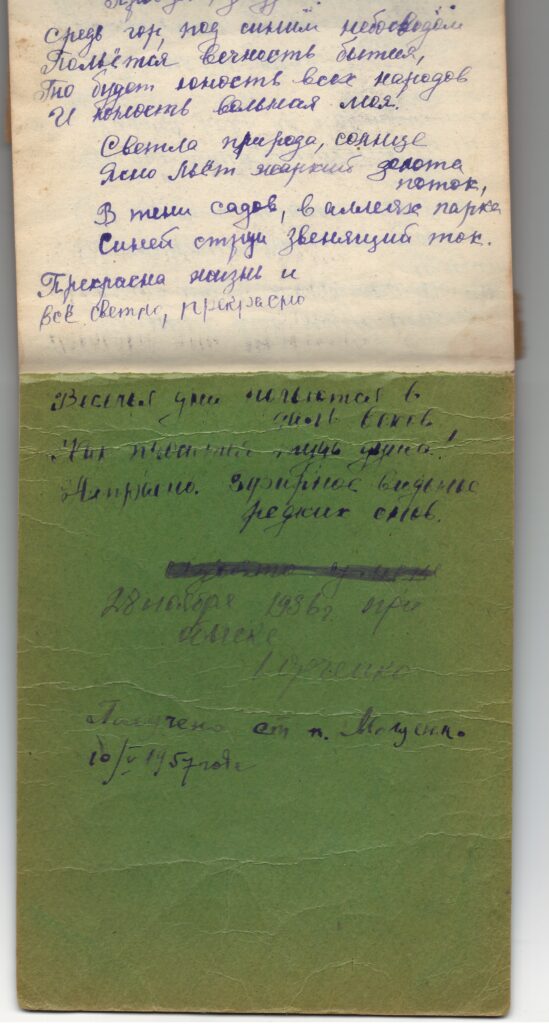

The back cover of H. Yurchenko’s notebook with a note about the 1986 search, DOKM

On the other hand, the system did not kill the girl Hanzia with a heart condition, but it broke her. After returning to Kramatorsk, she tried to forget everything and live a quiet life. She worked as a saleswoman in Kramatorsk bookstores. She lived to her retirement. She died in 2014, leaving behind numerous notebooks with her thoughts and experiences and a sick daughter. Such was the price for trying to be free in an unfree country.