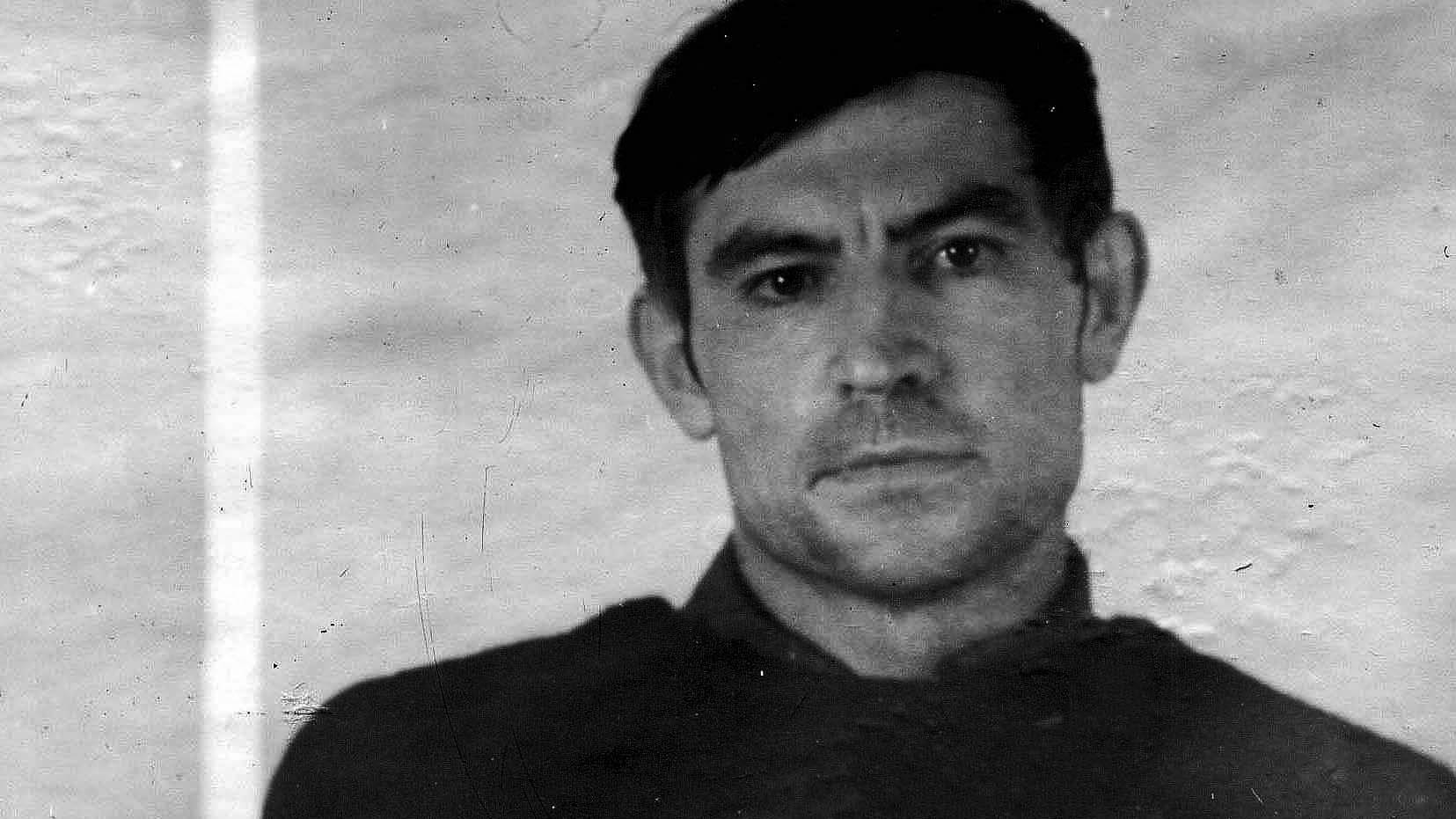

Vasyl Stus died in a punishment cell of the special-regime camp VS-389/36 (Russia). This happened 31 years ago—on September 4, 1985. Viktor Volodymyrovych Medvedchuk served as the defense attorney in the trial of the poet and dissident. Until now, no one has evaluated his work as a lawyer from a professional point of view, particularly in the context of adherence to the rules of legal ethics.

After Stus’s death, Viktor Medvedchuk headed the administration of President Leonid Kuchma; he later became the godfather to the daughter of Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin, Daryna; and he currently represents Ukraine in the Minsk negotiation process. Lawyers have studied the case archives and are ready to share their conclusions.

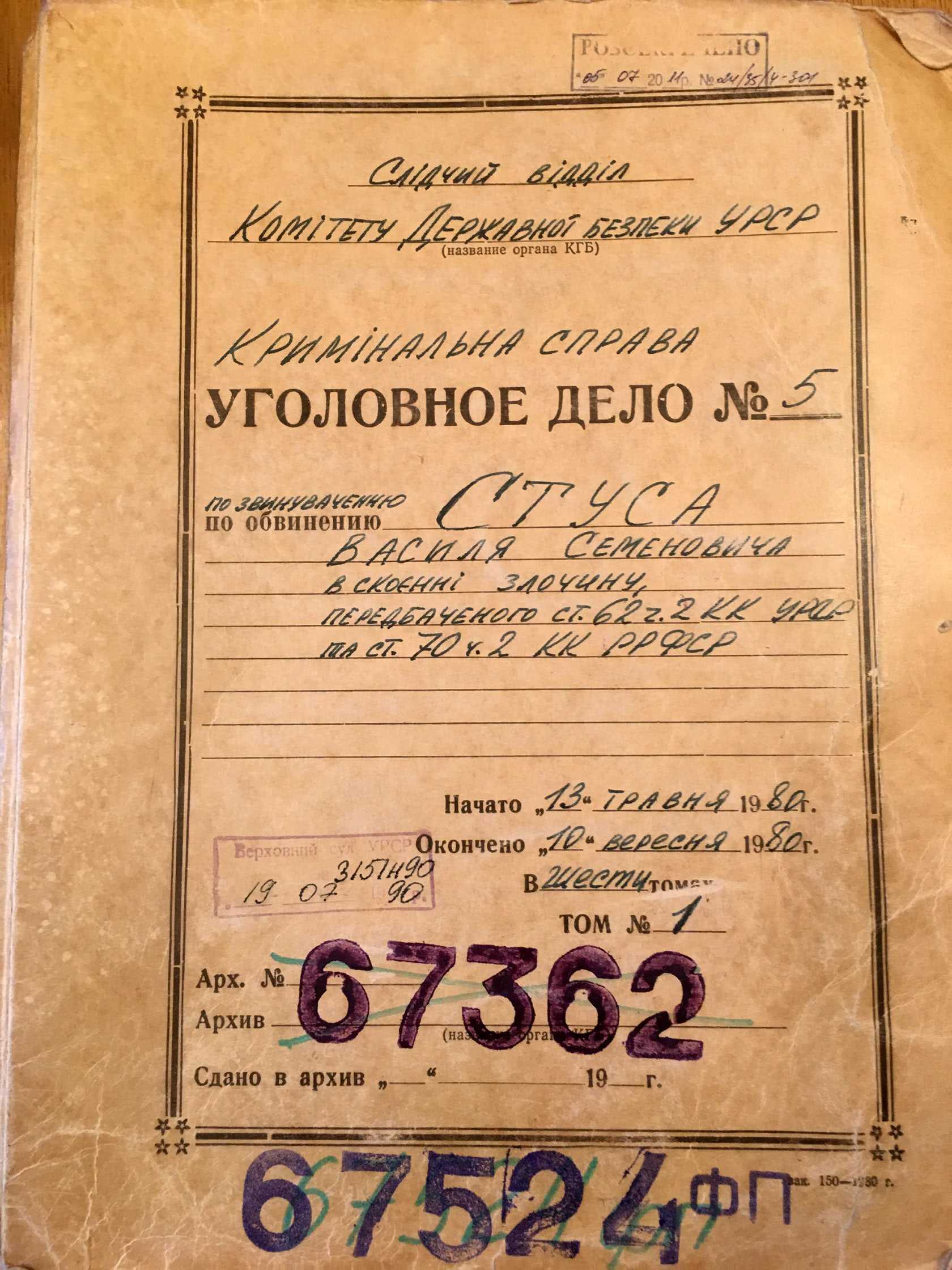

We have carefully familiarized ourselves with the archival criminal case No. 5 of the Investigative Department of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, charging Vasyl Semenovych Stus with committing a crime under Article 62, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR and Article 70, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR (“Anti-Soviet Activity and Propaganda”), as well as with the legislation that regulated legal practice at that time and the special and scholarly literature of the era.

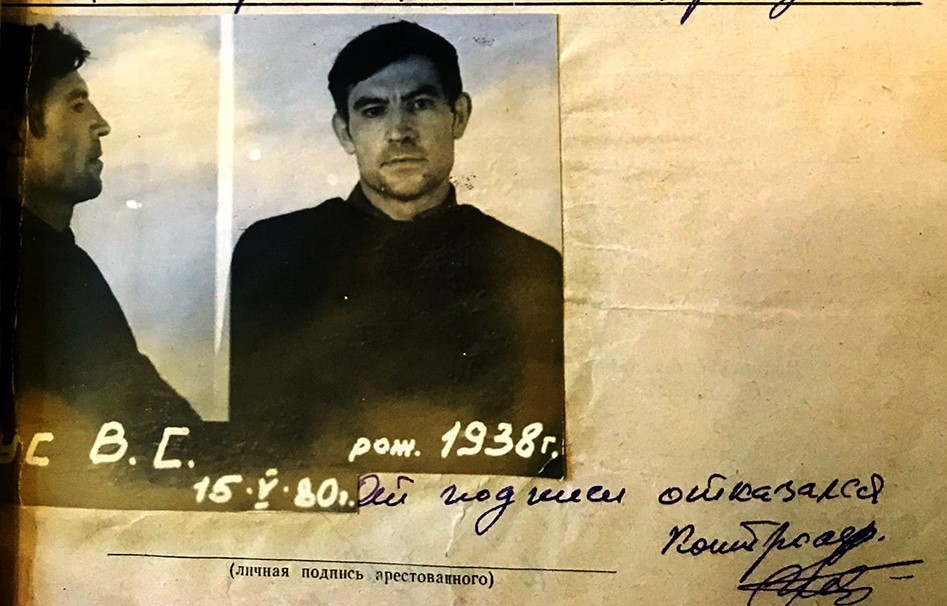

The criminal case against Stus was opened on May 13, 1980, and the preventive measure of detention was applied on May 15, 1980. The poet was accused of creating, storing, and distributing “for the purpose of undermining and weakening the Soviet government, hostile literature that slanders the Soviet state and social system,” thereby allegedly committing a crime under Article 62, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, as a person previously convicted of a particularly dangerous state crime (the indictment was drawn up on September 10, 1980, and approved by the Deputy Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR on September 12, 1980).

Stus was incriminated for, among other things, writing letters to Andrei Sakharov, Petro Hryhorenko, Levko Lukianenko, Anna-Halja Horbach from Germany, a member of “Amnesty International” Kristine Bremer, a letter to the Presidium of the Union of Writers of Ukraine, poems such as “Passportless Serf…,” “There are only two forms…,” “Here is the sun for you, said the man with the cockade,” “The wheels knock dully…,” and much more.

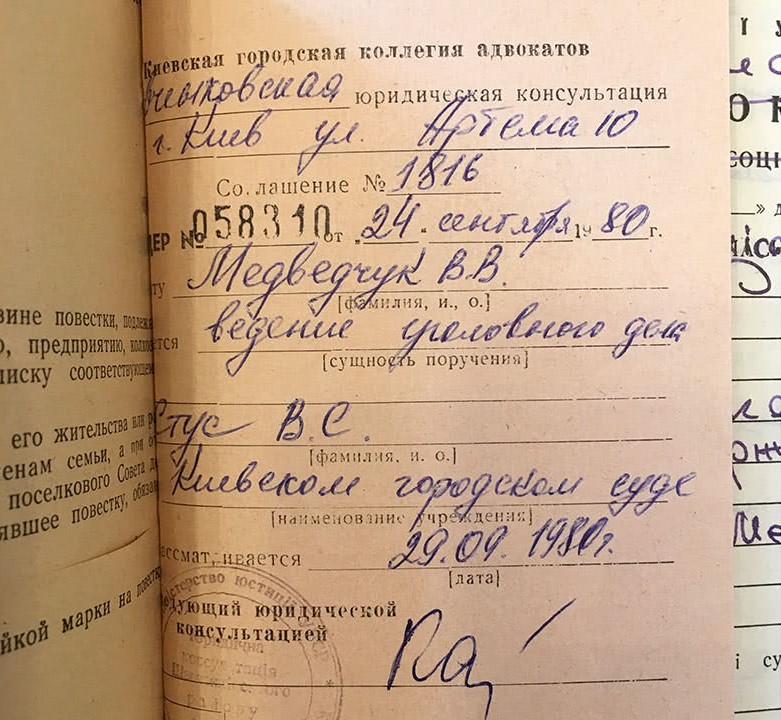

Lawyer V. V. Medvedchuk entered the case on the basis of warrant No. 058310 dated September 24, 1980, issued by the Shevchenkivska Legal Consultation of the Kyiv City Bar Association.

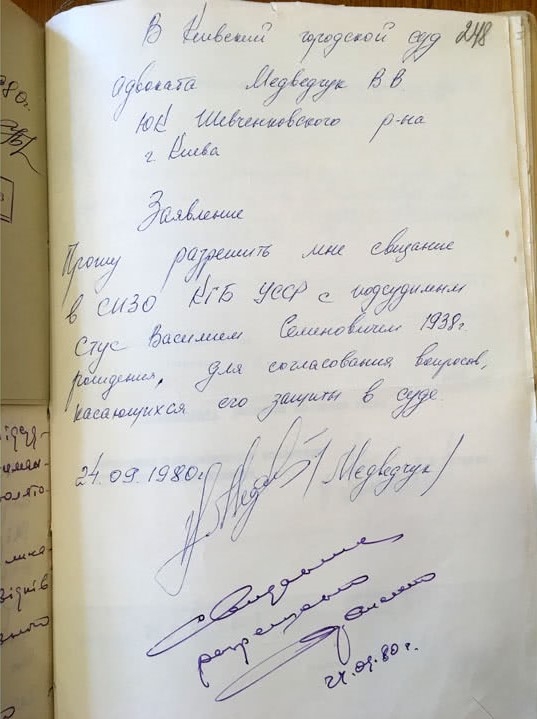

After entering the case on September 24, 1980, lawyer Medvedchuk wrote an application requesting permission for a meeting in the KGB pre-trial detention center of the UkrSSR with the defendant Stus “to coordinate matters concerning his defense in court.”

What exactly they discussed and how they coordinated their position is unknown; this information is protected by attorney-client privilege, and we will likely never know.

Although Stus’s friend, dissident Yevhen Sverstiuk, recalled:

“When Stus met his appointed lawyer, he immediately felt that Medvedchuk was a man of the aggressive Komsomol type, that he was not defending him, did not want to understand him, and, in fact, was not interested in his case. And Vasyl Stus dismissed this lawyer.” (Sverstiuk, Yevhen. “The Eternal Scenario.” Ukrainske Slovo. May 26, 2000)

Stus’s wife, Valentyna Popeliukh, has similar recollections.

Interestingly, Medvedchuk did not even familiarize himself with the criminal case and did not file such a motion—at this stage, the case was studied by another lawyer, Lyudmila Petrivna Korytchenko, who for unknown reasons refused to participate further in the trial (case sheet 179, volume 6).

Coincidentally, before defending Stus, Lyudmila Korytchenko was the lawyer in the case of another political prisoner—dissident Yurii Badzio—who was sentenced for anti-Soviet propaganda to 7 years in prison and 5 years of exile. Yurii Badzio tells the CHESNO civic movement that there was no adversarial process in court, and the essence of the defense at that time was not to deny the accusation but to mitigate the sentence.

“The authorities offered their own lawyer, and I didn’t make a problem out of it... They defended us according to one logic: to find something positive in our behavior and to contrast this with the accusation and the very idea of a crime. You see, all these trials were devoid of an adversarial element with the authorities, with the prosecutor’s office and prosecutors. It was about the lawyer interpreting the situation in such a way as to mitigate the sentence. Besides, the lawyer is the only link to one’s family. I had a good relationship with lawyer Lyudmila Petrivna, as did my wife Svitlana Kyrychenko. So I have no complaints about Lyudmila Korytchenko. She would come to see me, we would talk, she would treat me to a chocolate bar, probably from my wife. Everything was so humane.”

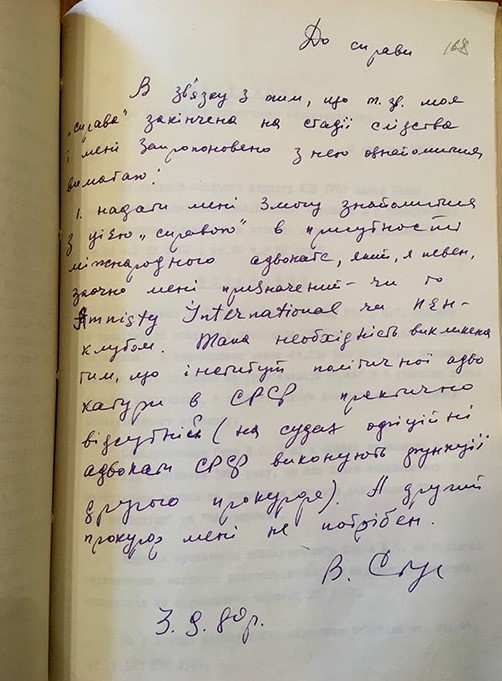

It is worth dwelling separately on Vasyl Stus’s attitude towards the bar and his defense counsel. On September 3, 1980, the accused submitted a statement in which he requested the opportunity to review the case with the help of an “international lawyer” brought in through the organization “Amnesty International” or “PEN Club,” noting that “The institute of political advocacy in the USSR is practically non-existent (in court, official USSR lawyers perform the function of a second prosecutor). And I don’t need a second prosecutor” (case sheet 168, volume 6).

As was to be expected, senior investigator Major Selyuk denied Stus an independent lawyer.

The Trial: Stus insists—he is guilty of nothing.

The lawyer admitted his client's guilt.

At 10 a.m. on September 29, 1980, the trial began in the Kyiv City Court on Volodymyrska Street.

The trial was held in closed session; even Stus’s wife, Valentyna Popeliukh, was not allowed in. It is interesting to trace lawyer Medvedchuk’s line of conduct at different stages of the trial.

In essence, Stus conducted his own defense. He moved to disqualify the entire court, beginning his motion with the words “My dear court...” Stus argued that a Soviet court by definition could not consider his case objectively.

The defendant also filed a motion to allow representatives of international organizations to be present at the trial, including “representatives of the UN Commission on Human Rights,” “representatives of the International Law Association—Amnesty International,” and others.

Stus demanded an open and public hearing of his case:

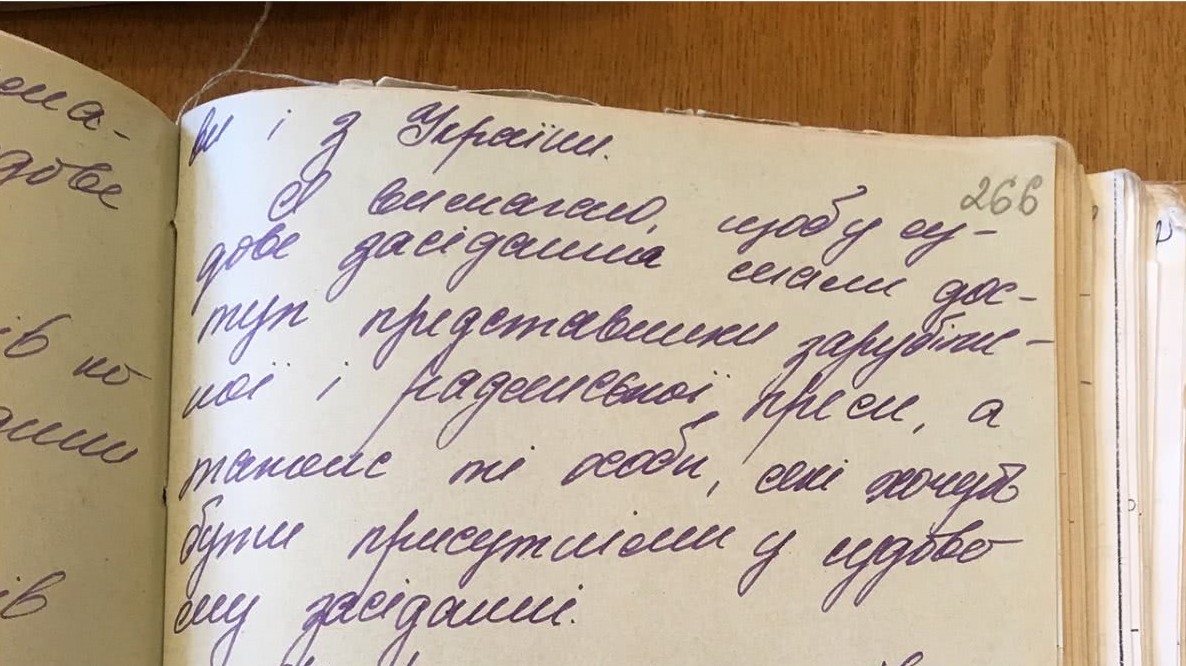

“I demand that representatives of the foreign and Soviet press, as well as those persons who wish to be present at the trial, have access to the courtroom.”

These were entirely fair demands. What was lawyer Medvedchuk’s reaction?

He supported neither the disqualification motion nor the defendant’s motion, instead stating that he relied “on the court’s consideration.”

And the court, of course, did not grant the disqualification (case sheets 259-260, volume 6), and the motion for a public trial was also effectively denied.

Stus, obviously realizing that lawyer Medvedchuk would not defend him, stated:

“I dismiss lawyer Medvedchuk and, in general, any Soviet lawyer. I demand a lawyer from an international legal organization.”

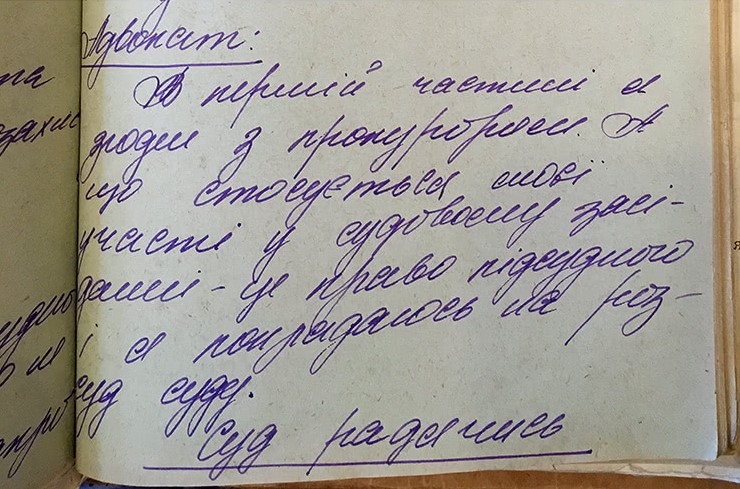

The prosecutor asked to deny Stus’s motion to involve a lawyer from an international legal organization, arguing that such participation was not provided for by Soviet legislation. In the prosecutor’s opinion, Medvedchuk’s participation in the trial was mandatory because “the defendant... does not have a legal education and cannot fully defend his interests himself.” And Medvedchuk agrees with the prosecutor, denying Stus the right to be defended by international lawyers, and as for his own candidacy’s participation in the trial, he relies on the court’s discretion:

“In the first part, I agree with the prosecutor. As for my participation in the court session—that is the defendant’s right, and I rely on the court’s discretion.”

After the rights of the accused were explained, Stus stated that he needed a translator “in case the witnesses testify in Russian” (case sheet 264, volume 6).

After the indictment was read, when asked by the presiding judge whether he understood the charge and whether he pleaded guilty, Stus replied:

“What exactly I am accused of is clear to me. But I do not plead guilty.”

We consider this position, expressed by the defendant Stus from the very beginning of the trial, to be principled and very important. Based on this, the defense attorney should have built his defense strategy. But the lawyer, as we will see, chose a different path.

Subsequently, Stus refuses to testify; he chose a tactic of silence and disregard as the court began to examine the case materials—the poet’s letters, his poems, the expert opinions, and also to question witnesses. And here the lawyer’s role is also interesting.

In particular, one of the prosecution witnesses—Mykola Ivanovych Siryk—claimed to have allegedly met the poet in the punishment cell when he was serving his previous sentence.

Mykola Siryk:

“I came to the conclusion that Stus is an outspoken enemy of the Soviet government...,” Siryk stated, claiming that Stus told him, “that Ukrainians want to get out of the ‘occupation’ of Russia. Stus proposed carrying out terrorist acts against the Soviet government,” “he called on me to conduct agitation and propaganda against the Soviet government, up to and including terror, that all means against the Soviet government are good.”

These remarks elicited open indignation from Vasyl Stus:

“I don’t know Siryk; he is a provocateur. I am not acquainted with him; I have never exchanged a single word with him.”

Medvedchuk, meanwhile, remains silent. He will not ask this witness a single question. However, during the examination of the well-known dissident movement representative Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, who, of course, gave a positive characterization of Stus, he will ask about how the witness can characterize Stus’s political views, as well as about the poet’s poems that have an anti-Soviet orientation (case sheet 300, volume 6).

The response of witness Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska to Stus's question is interesting:

“I am aware that violating the secrecy of correspondence is punishable by law. Kristine Bremer, a member of the Socialist Party of the FRG, has no connection to Ukrainian nationalism. I am not aware that physical torture was used against Stus in the KGB on August 8, 1980, but if Stus says so—then it is true.”

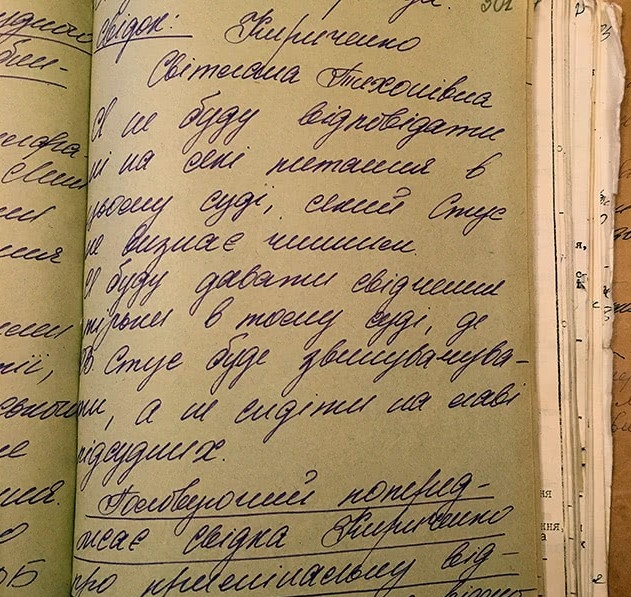

Even more vivid and interesting is the testimony of witness Svitlana Tykhonivna Kyrychenko:

“I will not answer any questions in this court, which Stus does not recognize as valid. I will only testify in a court where Vasyl Stus is the accuser, not sitting in the dock.”

The presiding judge immediately began to warn the witness about the responsibility for refusing to testify under Article 179 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR, but this did not frighten the witness; she replied: “I will not give any testimony in this court.”

The prosecutor began to demand that the court initiate a criminal case against the witness, and defense attorney Medvedchuk again stated, “I rely on the court’s decision” (case sheet 302, volume 6).

The court retired to the deliberation room and subsequently announced a decision to open a criminal case against S. T. Kyrychenko under Article 179 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR (case sheets 261-262, volume 6).

One can only admire the courage of Svitlana Tykhonivna, who stood up to the pressure of the repressive Soviet system and did not betray Stus, receiving 3 months of correctional labor and constant persecution.

Another witness, Valeriia Viktorivna Andriievska, born in 1938, also gave positive testimony regarding Vasyl Stus and stated that:

“Stus is a gifted person. In the letter that Stus wrote to his friends in Kyiv, including me, there are no anti-Soviet manifestations.”

Without the Right to a Final Word

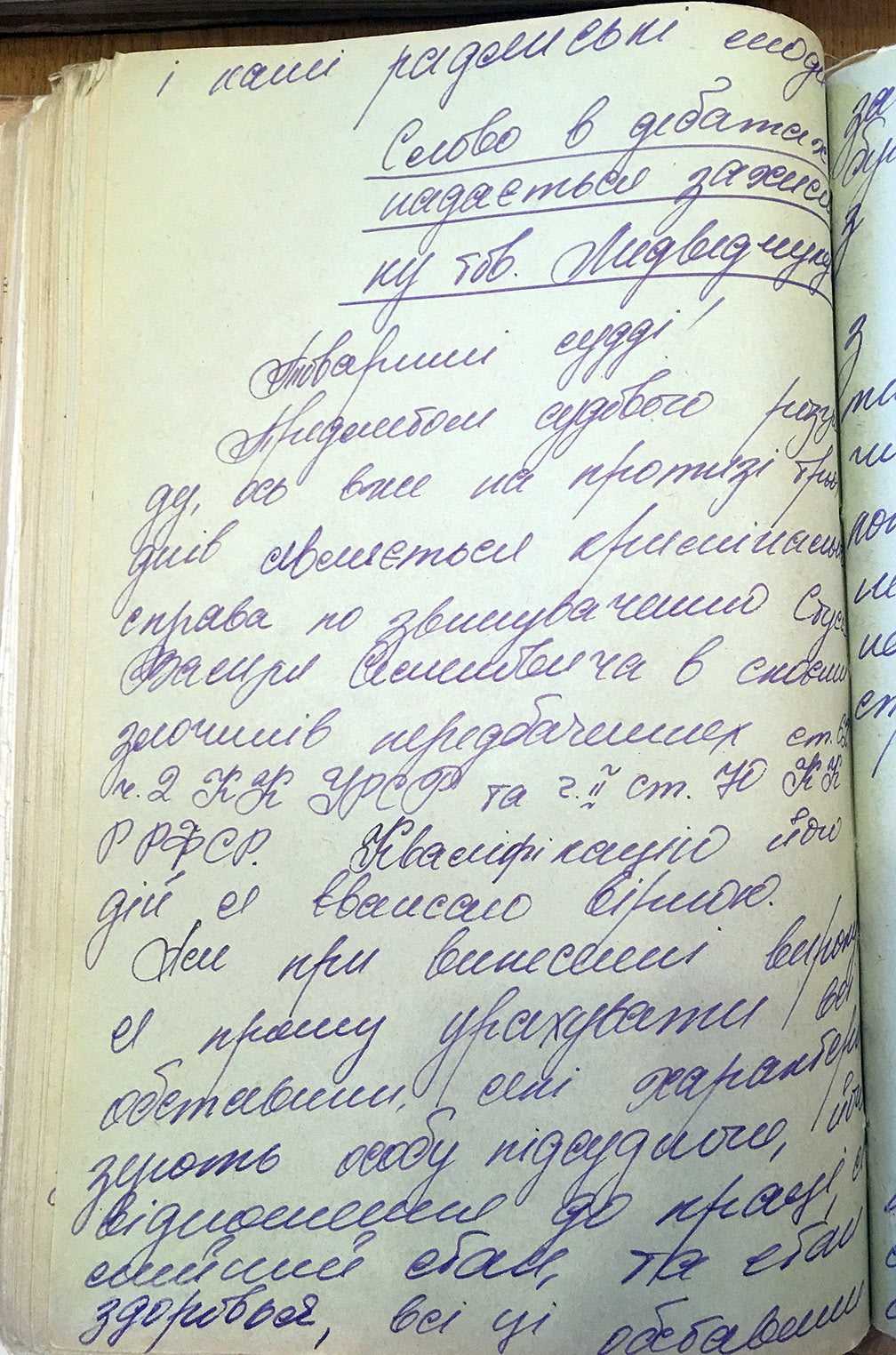

Eventually, the court moved to the closing arguments stage. After the speech by prosecutor Armasov, who requested 10 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile for the “especially dangerous recidivist” (case sheets 306-307, volume 6), came the climax of the trial: the floor was given to defense attorney Medvedchuk. His speech (remarkably brief) is worth quoting in full (case sheets 307-308, volume 6):

“Comrade judges!

The subject of this judicial review, which has now been ongoing for three days, is the criminal case charging Stus, Vasyl Semenovych, with committing crimes under Article 62, Part 2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine and Part 2, Article 70 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR. I consider the qualification of his actions to be correct.

However, when delivering the verdict, I ask you to take into account all the circumstances that characterize the defendant’s personality, his attitude to work, his physical condition, and his health; all these circumstances deserve attention and require careful study on your part.

This is connected not only with the requirement of the law but also with the fact that only by taking them into account when choosing a measure of punishment will your verdict, delivered in the deliberation room, be well-founded and just.”

It is interesting to know what Vasyl Stus said in his last word.

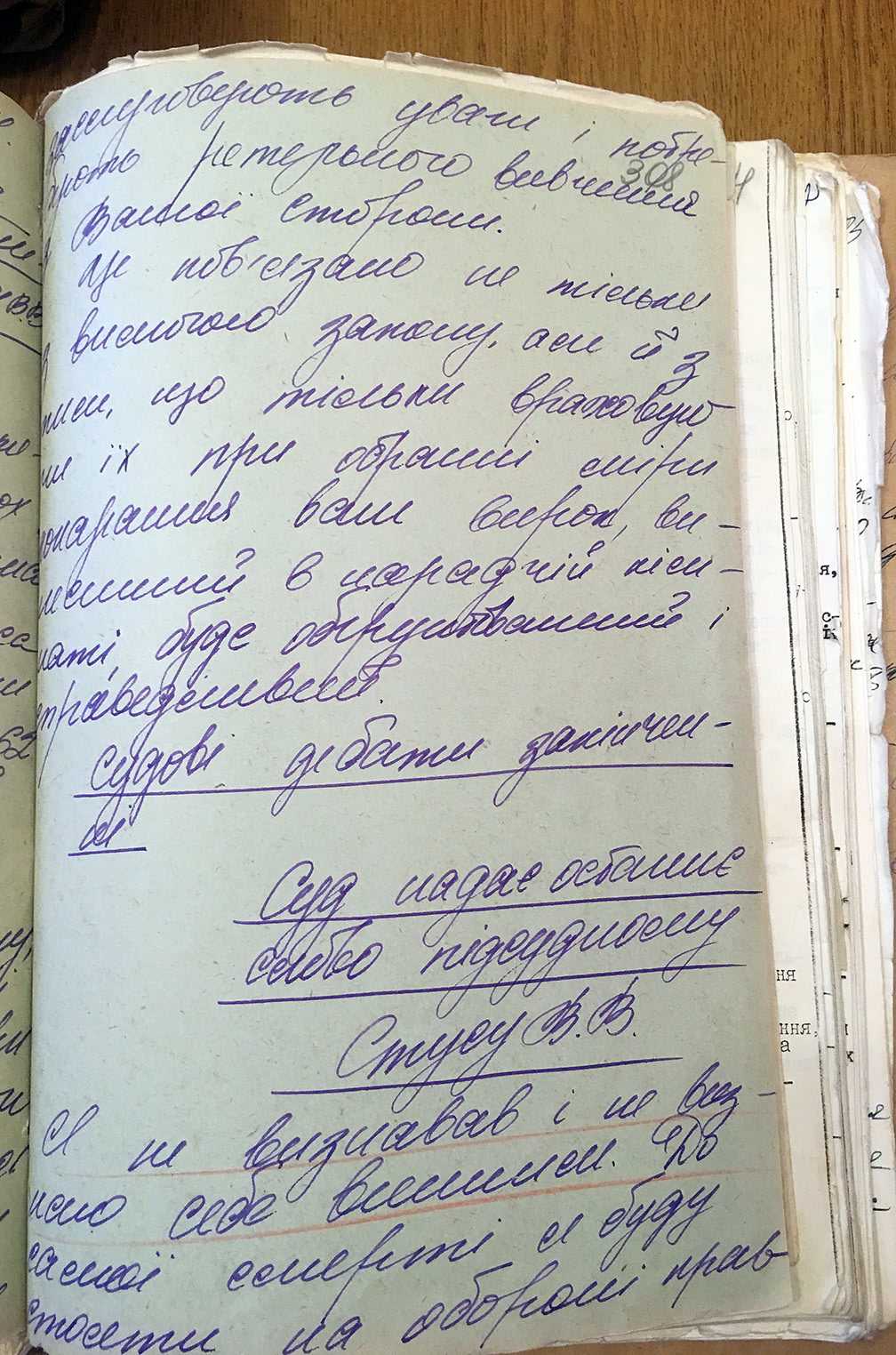

But it suddenly turns out that the court never gave Stus the opportunity to make a final statement.

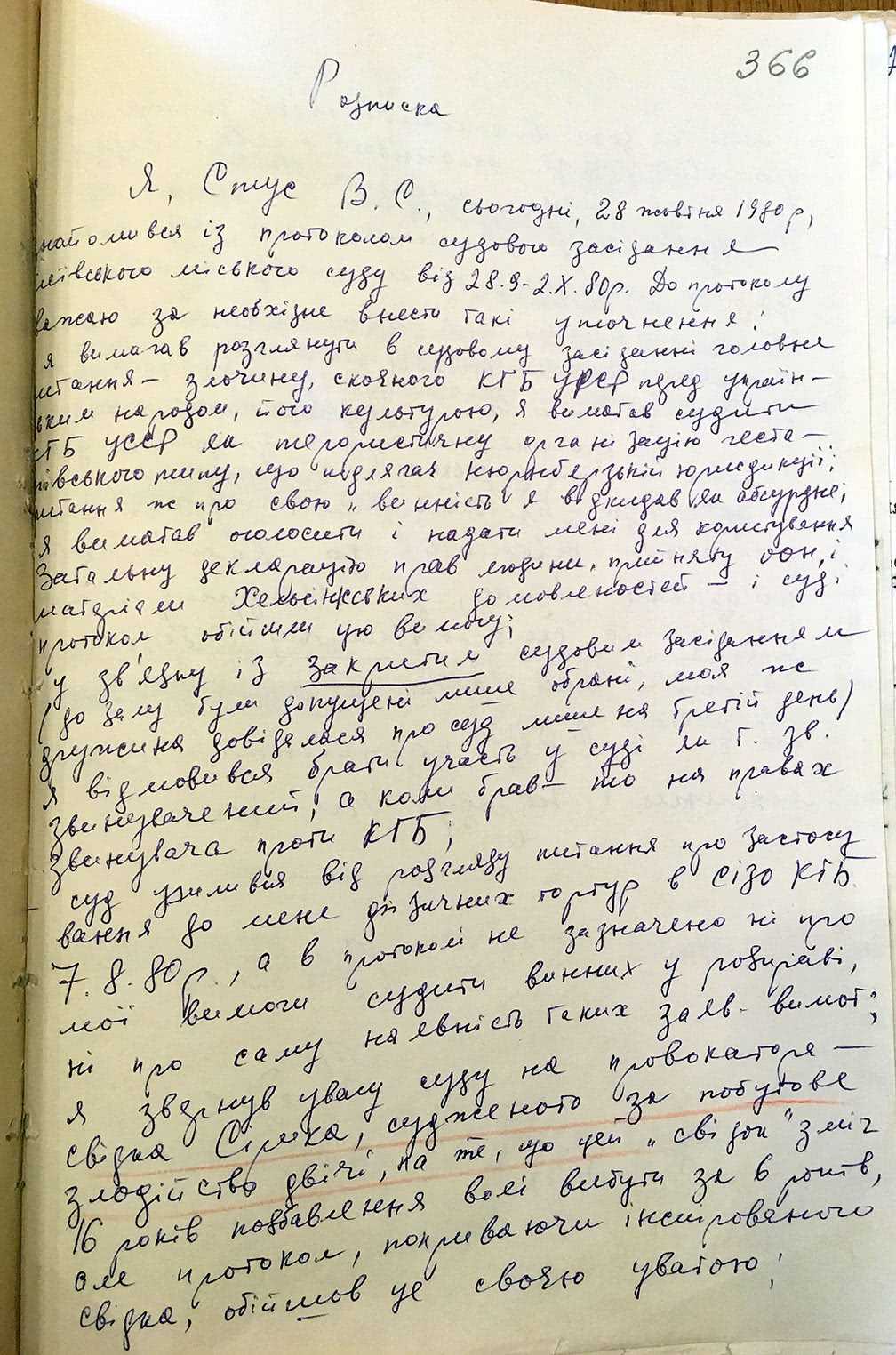

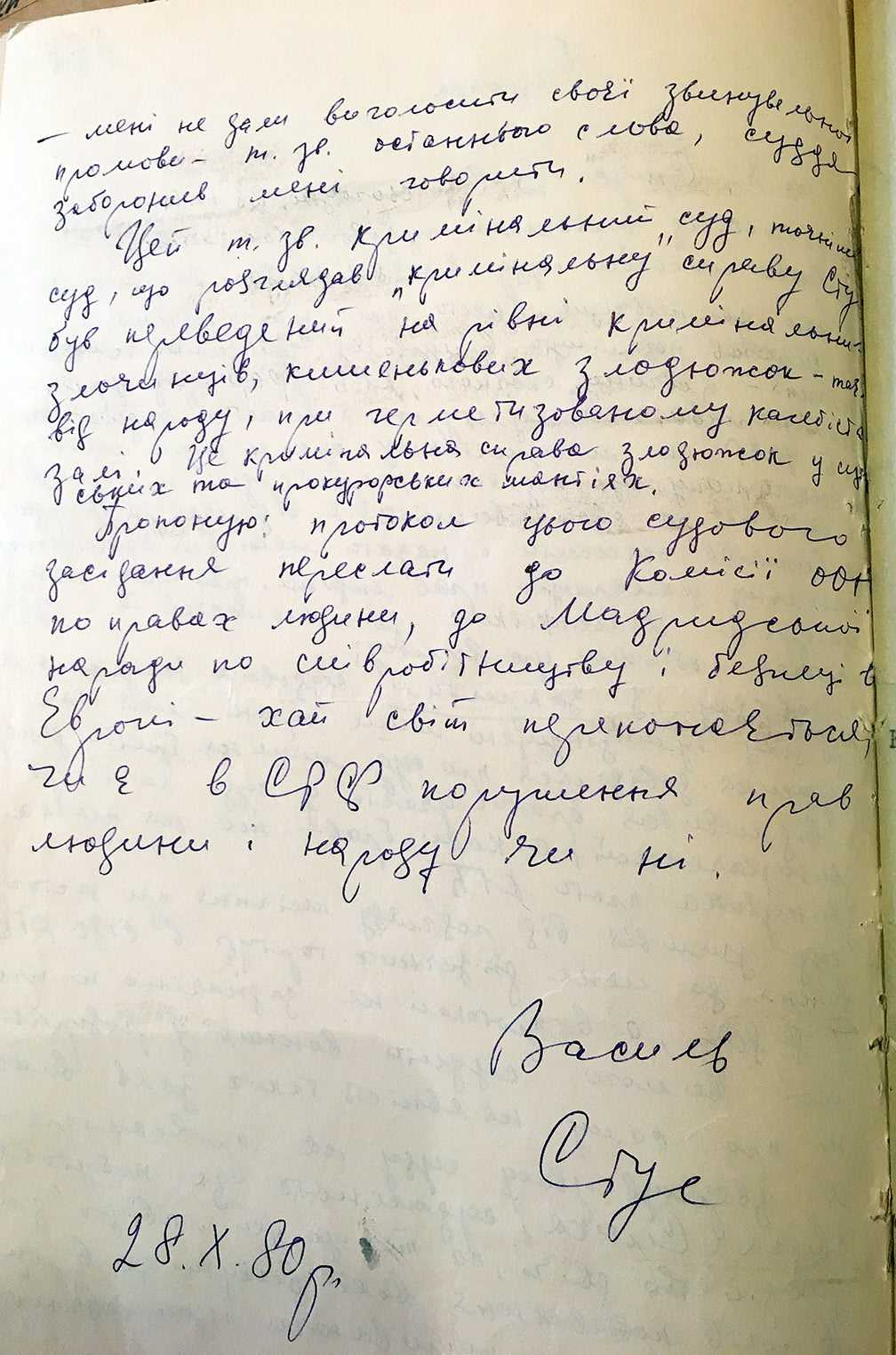

In the receipt written by the dissident after reviewing the verdict (case sheets 366-367, volume 6), we read:

“I consider it necessary to add the following clarifications to the protocol:

- I demanded that the court session consider the main issue—the crime committed by the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR against the Ukrainian people and its culture; I demanded that the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR be tried as a terrorist organization;

- I demanded that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN, and the materials of the Helsinki Accords be announced and provided to me for use—both the court and the protocol ignored these demands;

- The court evaded consideration of the issue of the use of physical torture against me in the KGB pre-trial detention center on 08/07/1980, and the protocol noted neither my demands to try those guilty of the reprisal nor the very existence of such statements—demands;

- I was not allowed to deliver my accusatory speech, the so-called final word; the judge forbade me to speak.”

Thus, according to Stus’s statement, he was not given the opportunity to deliver a final word—although the protocol states that Stus supposedly said in his final word (case sheet 308, volume 6):

“I have not and do not plead guilty. Until my death, I will stand in defense of truth against lies, of honest people against murderers,

of Jesus Christ against the devil!”

The verdict was announced the next day—October 2, 1980.

Stus decided not to appeal the verdict—he had no faith in Soviet courts.

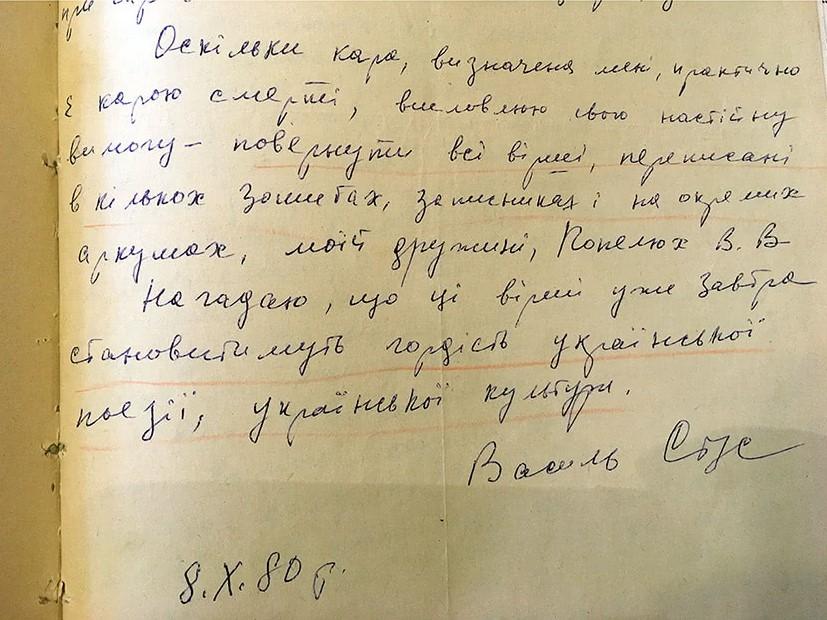

He also understood that this verdict was effectively a death sentence for him—as he would not survive another multi-year stay in the camps (case sheet 365, volume 6).

Medvedchuk’s Position: What Doesn’t Add Up

Medvedchuk has publicly commented on his position during that trial several times. For example, in 2012, Viktor Medvedchuk commented on his defense activities: “In those times, there was an article that provided for criminal liability for such actions. He [Stus] was convicted under this article” (Ukrainska Pravda, April 4, 2012, with reference to a video blog).

In this video blog, the lawyer confirms the fact that he admitted his client’s guilt in court. Moreover, Medvedchuk claimed that Vasyl Stus himself stated in the court session that he “always has and always will speak out against the Soviet system and Soviet power.”

However, upon detailed study of the trial transcript, we did not find such a statement in the document. There is no mention of such a position by Vasyl Stus in the case materials.

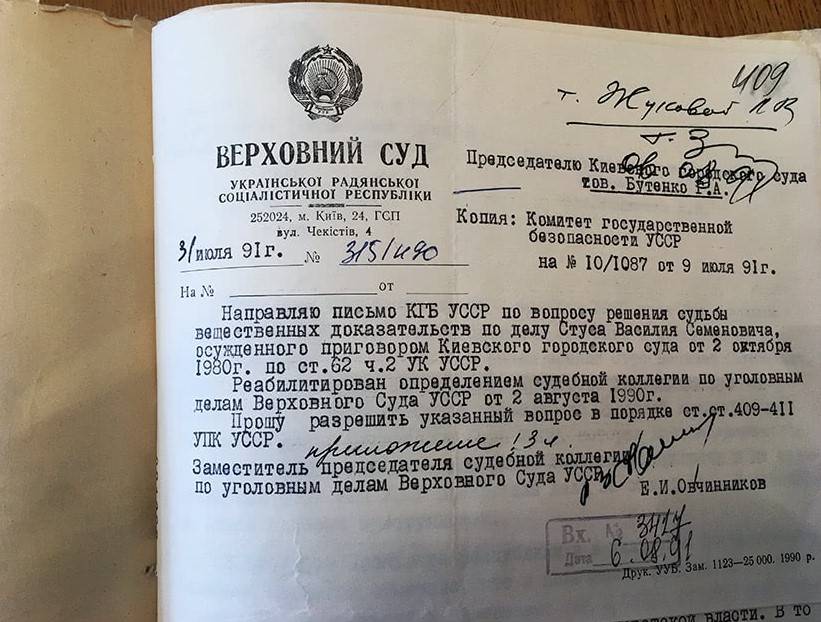

In addition, lawyer Medvedchuk claims that Stus’s sentence was overturned on the basis of the Law of Ukraine “On the Rehabilitation of Victims of Political Repression in Ukraine” of April 17, 1991, in connection with the repeal of Article 62 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR. But in fact, this article was only removed from the Criminal Code by the Law of Ukraine of June 17, 1992. And the case materials testify to something completely different.

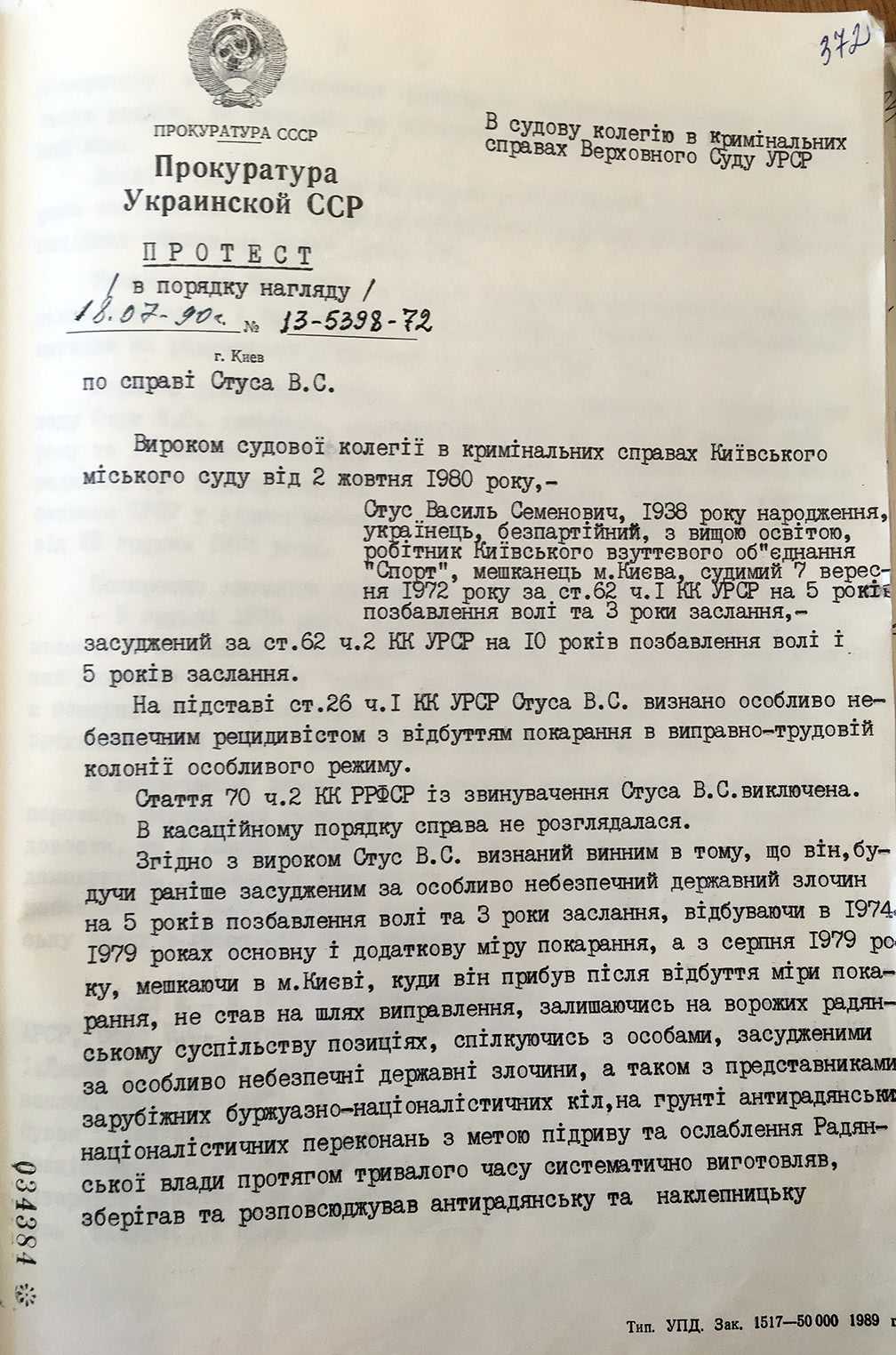

Specifically: as early as July 18, 1990, the prosecutor of the UkrSSR, M. O. Potebenko, filed a protest, citing the fact that there was no corpus delicti in Vasyl Stus’s actions at all—since he “did not make public calls for violent actions with the aim of undermining and weakening Soviet power” (case sheets 372-388, volume 6).

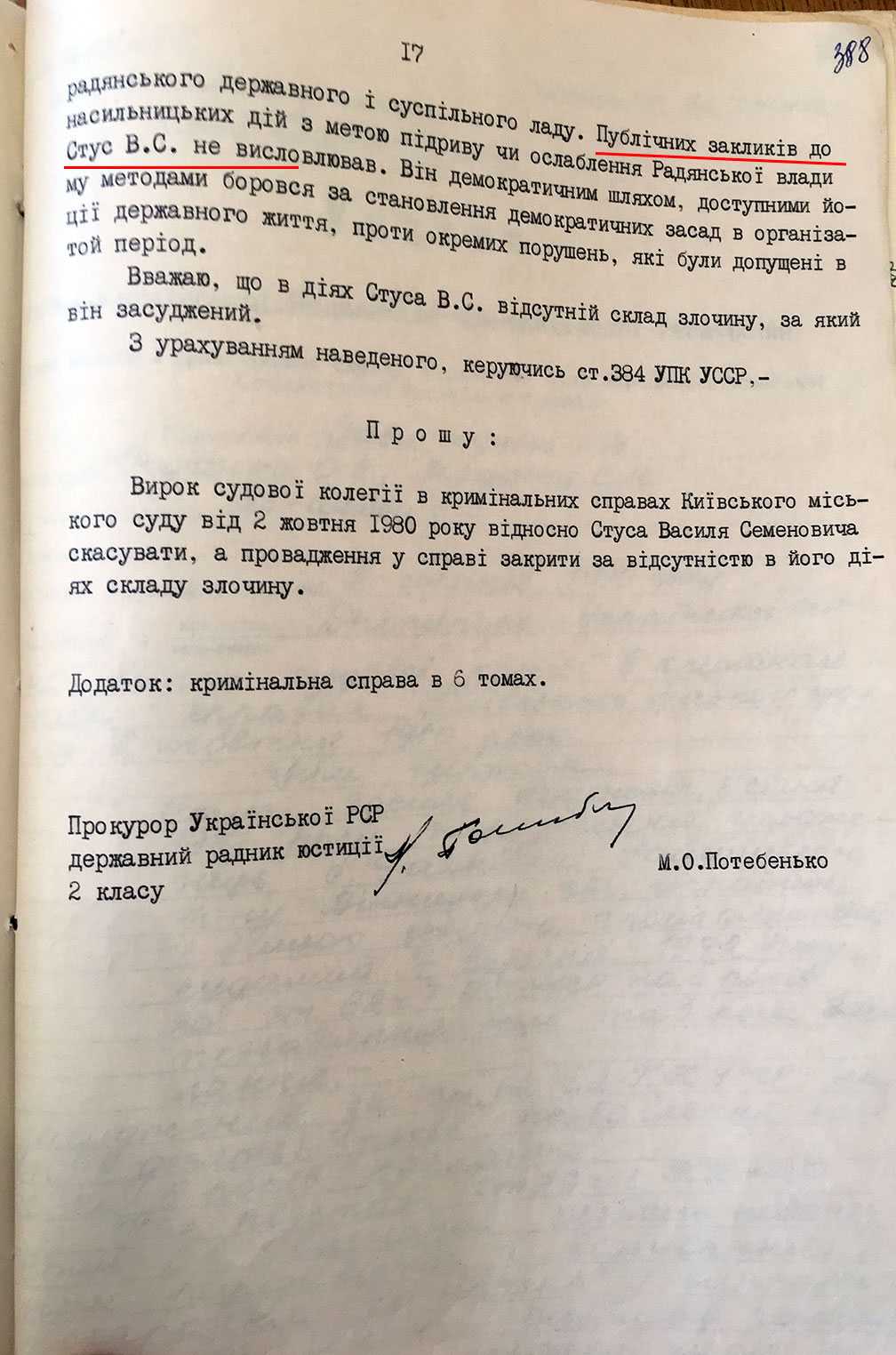

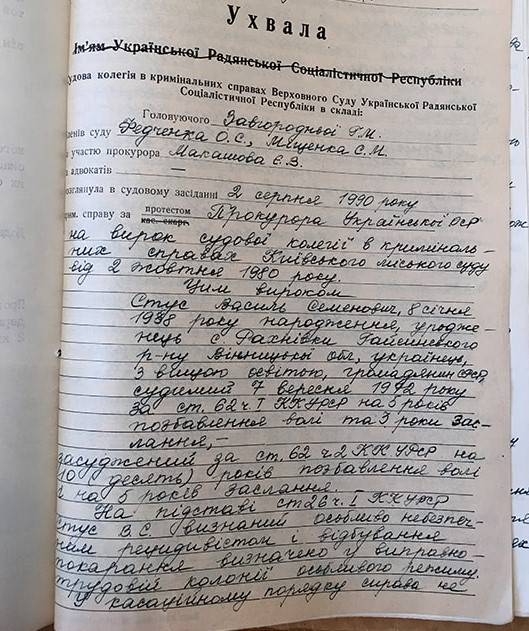

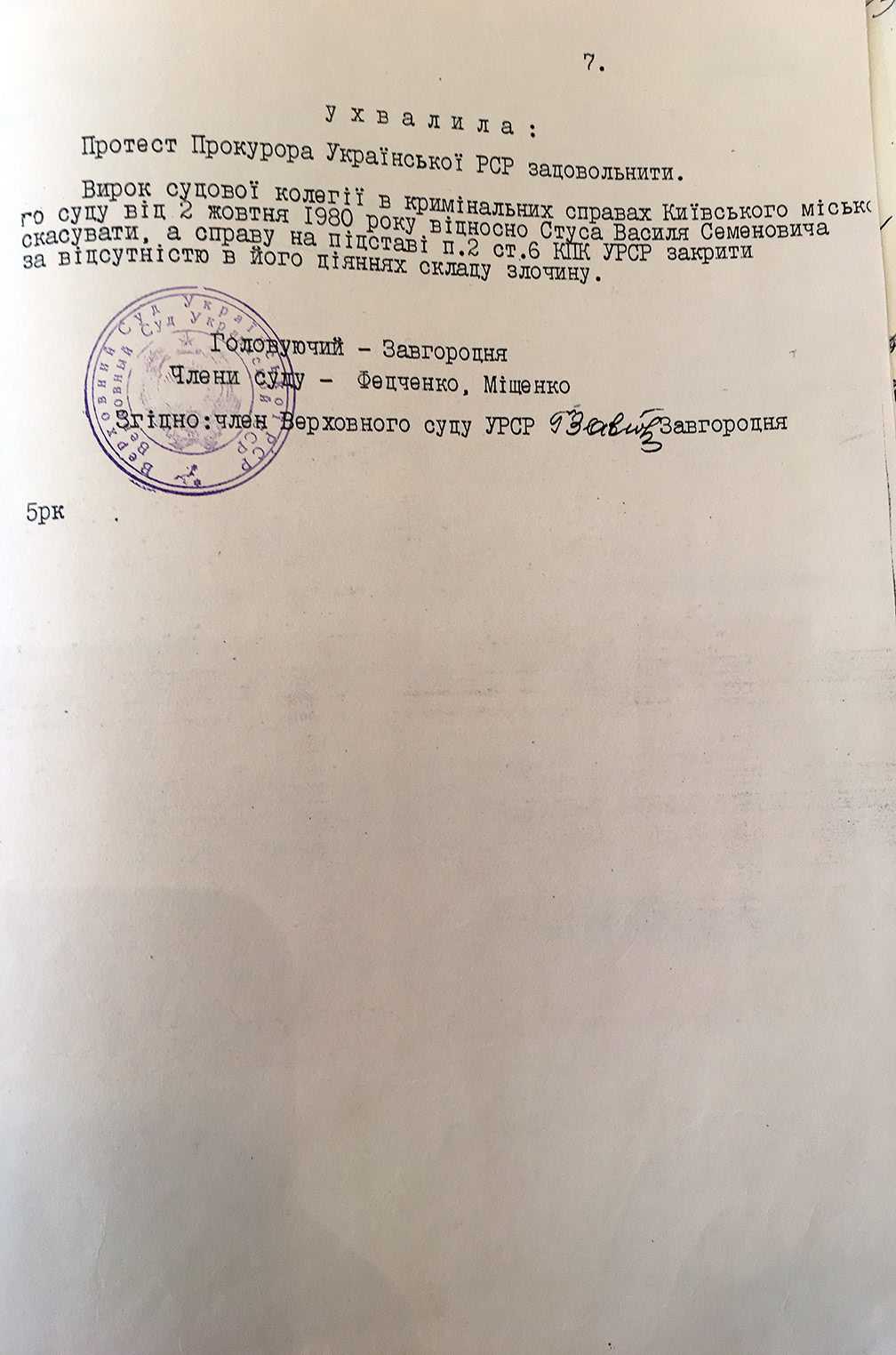

On August 2, 1990, the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR reviewed the Prosecutor’s protest and decided to grant the protest, annul the verdict, and close the case due to the absence of corpus delicti (case sheets 389-396, volume 6).

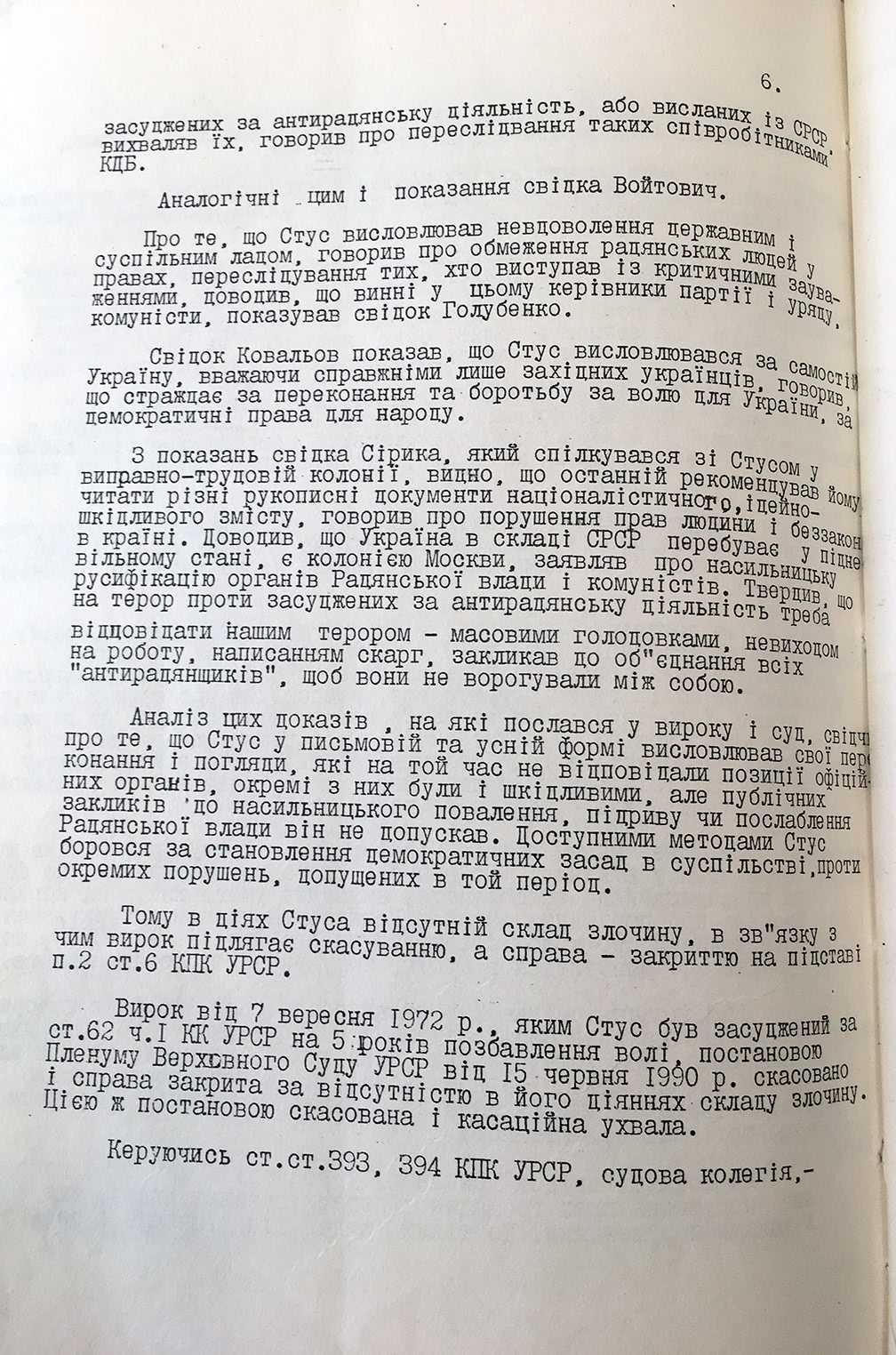

The reasons why the Supreme Court of the UkrSSR annulled the verdict were as follows:

“...he did not make public calls for the violent overthrow, undermining, or weakening of Soviet power. Stus fought by permissible methods for the establishment of democratic principles in society, against individual violations committed during that period.”

Thus, the Supreme Court of the Ukrainian SSR back in 1990 (while the relevant article of the Criminal Code was still in force and almost a year before the adoption of the law on the rehabilitation of victims of political repression) directly confirmed the position that Stus held in court. The fact that Stus was acquitted by a Soviet court (!) under existing Soviet legislation (!!) undoubtedly confirms that the lawyer had all legal grounds to contest and not admit Stus's guilt in the Kyiv City Court. So much for “relying on the court's consideration”...

This is precisely why the question arises: did lawyer Medvedchuk properly defend his client?

Legislation and Legal Ethics in the Soviet Era: Lawyer Medvedchuk Had No Right to Take Such a Position

To sort this issue out, let’s turn to the legislation and specialized literature of that time.

According to Article 23 of the Fundamentals of Criminal Procedure of the USSR of December 25, 1958:

Firstly, “A defense attorney is obligated to use all means and methods of defense specified in the law in order to clarify circumstances that exonerate the accused or mitigate his responsibility, and to provide the accused with necessary legal assistance.

From the moment of being admitted to participate in the case, the defense attorney has the right: to have a meeting with the accused; to familiarize himself with all materials of the case and to copy necessary information from it; to present evidence; to file motions; to participate in the judicial proceedings; to file challenges; to appeal against the actions and decisions of the investigator, prosecutor, and court. In addition, with the permission of the investigator, the defense attorney may be present during the interrogations of the accused and during other investigative actions carried out at the request of the accused or his defense attorney.”

And here the question arises: did lawyer Medvedchuk fulfill his legally established duty—did he use all means and methods to clarify the circumstances of the case that would exonerate the accused?!

The case materials show that lawyer Medvedchuk did not file a single protest or motion, did not familiarize himself with the case materials, did not file a single complaint, explanation, piece of evidence, etc.!

This could be called inaction, but the lawyer might argue that he independently determines the defense strategy. But what about a lawyer admitting a client's guilt when the client denies it? Does (did) a defense attorney have the right to do that?

The current Law of Ukraine “On the Bar and Practice of Law” directly prohibits a lawyer from taking a position in a case contrary to the client’s will (para. 3, part 2, art. 21), but perhaps there were different rules and prohibitions for lawyers in the Soviet era?

It turns out there were not. The general purpose of a lawyer's activity precludes the possibility of admitting a client’s guilt. According to Article 7 of the Law of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics “On the Bar in the USSR” of November 30, 1979, “a lawyer is obligated in his activity to strictly and unwaveringly observe the requirements of current legislation, to use all means and methods provided by law for the defense of the rights and legitimate interests of citizens and organizations who have sought his legal assistance.”

Soviet legal scholars also wrote about this. For example, M.S. Strogoivch (Course of Soviet Criminal Procedure, vol. 1, pp. 247-248): “If the accused has not pleaded guilty, denies the charge against him, then the lawyer under no circumstances can take a different position in the case; he is obliged to prove the innocence of his client.”

Legal literature of that time also stated: “A lawyer's admission of the defendant's guilt when the latter denies it should be considered a violation of professional duty, a veiled form of refusal of defense, and consequently, a gross violation of the right to defense” (Ginzburg G.A., Polyak A.G., Samsonov V.A. — “The Soviet Lawyer” M., Yuridicheskaya Literatura, 1968, p. 8).

At the same time, some authors in their professional publications indicated that if the client's guilt is proven, and there is not the slightest doubt as to the proof of his guilt, the lawyer has the right, after obtaining the client's consent, to admit his guilt, and if the client does not give such consent, the lawyer is obliged to withdraw from the case if he does not agree with the accused's position (Petrukhin I. Evidence of Innocence and the Lawyer's Position in Court. — “Sovetskaya Yustitsiya,” 1972, No. 10).

The aforementioned M. S. Strogoivch (Course of Soviet Criminal Procedure, vol. 1, pp. 247-248), by the way, essentially described the situation that arose in Stus's case, only the lawyer's position here should have been different: “If the defendant denies his guilt, and the defense attorney asserts that the defendant is guilty but deserves leniency, this means that the defense attorney is contesting the exculpatory evidence presented by the accused..., and this is an accusatory activity, not a defensive one.”

In summary, we arrive at two main conclusions:

- V. Medvedchuk, as a lawyer defending V. Stus, did not use all means and methods to clarify the circumstances of the case in order to exonerate the accused, and did not provide the latter with proper legal assistance, thereby violating the requirements of Art. 23 of the Fundamentals of Criminal Procedure of the USSR of December 25, 1958 (the normative act in force at the time of the case consideration).

- By admitting the guilt of his client Stus in court (while the client himself denied his guilt), lawyer Medvedchuk violated his professional duty, effectively refused to defend Stus, thereby grossly violating the latter’s right to a defense in court.

Ultimately, such actions by lawyer Medvedchuk created the groundwork for and contributed to the adoption of an unlawful court decision (which was later confirmed by a higher court), the execution of which, under the realities of the Soviet repressive system, unfortunately, led to the death of Vasyl Semenovych Stus.

Some Worldview Conclusions: Personal Position of the Authors

We—the Ukrainian Bar, which historically and by many signs is the successor to the Soviet bar that produced lawyer Medvedchuk—must apologize to the citizens of Ukraine, a country that now, as in the last century, is fighting for its independence.

Apologize for the venality, unprofessionalism, and collaboration of representatives of the profession with the imperial anti-Ukrainian regime.

The legal profession in Ukraine is currently going through difficult times. Ukrainian society is also going through difficult times.

Many lawyers who devotedly defended the rights of detained citizens during the Maidan and bravely, risking their lives, fought against the repressive machine, now represent the interests of judges suspected of committing crimes—issuing unjust decisions, which caused, among other things, death, loss of health, and violation of the dignity of the people against whom they pronounced these unjust decisions.

However, the essence of the legal calling is to defend the rights of the client. Lawyers do their job. Professionally. With dignity. And no one, as far as we know, admits the guilt of their clients. Even in such difficult, and sometimes obvious, cases.

When you familiarize yourself with the materials of the KGB of the UkrSSR case against Stus, you understand the moods in society. Those who worked and lived during the Soviet era understand this perfectly. There was no and could be no mass opposition of society against the government. The value of freedom of speech and the right to one’s own opinion, the right to the development of the nation were scorched out by the Soviet (Moscow) government for decades—through war, repression, the Holodomor.

There were very few who could resist with words, and even fewer who acted. However, lawyer Medvedchuk was not required to become a dissident like his client, to make loud statements, to give speeches, to conflict with the repressive imperial apparatus. His professional duty was to do his job—qualitatively, professionally, in accordance with the requirements of the current legislation. This alone—as the higher court later confirmed—could have led to the acquittal of Vasyl Stus, or at least to the imposition of a more lenient punishment. A person’s life was at stake. Unfortunately, the lawyer failed to fulfill his duty. Moreover, defense attorney Medvedchuk effectively became an accomplice of the prosecution, acting contrary to both the norms of law and the requirements of professional ethics.

Restoring historical justice, establishing the truth, and acknowledging shortcomings are the key to the development of the legal profession in Ukraine.

We call on the Ukrainian Bar, both personally each lawyer and in the person of the representative bodies of the bar, in particular the Ukrainian National Bar Association, to publicly recognize the violation of the rights of his client Vasyl Stus to a defense by lawyer Viktor Medvedchuk.

Glory to Ukraine!

Epilogue

“How good it is that I do not fear death

and do not ask if my cross is heavy,

that before you, judges, I do not bow

in anticipation of unknown miles,

that I lived, loved, and did not gather filth,

hatred, curses, or remorse.

My people, I will yet return to you,

when in death I turn back to life

with my suffering and my unembittered face.

As a son, I will bow low to you

and look honestly into your honest eyes,

and in death, I will become one with my native land.”

Vasyl Stus.