I have grown old. And slow. At my age, others are already celebrating the second or third edition of their memoirs. But I haven’t even gotten to the first. And it’s not because there’s nothing to recall or because senile dementia has taken its toll. No, no. Quite the opposite—often I, like any other normal person my age, suddenly feel the urge to remember something—“My dear friend, / do you remember? / the apple blossoms of Rzhyshchiv / and the bumblebees...”—but then I immediately catch myself. Everything somehow turns out wrong for me, not like it does for other people—it’s about the wrong thing, at the wrong time, and against the grain.

I remember this—April 1971, my first month in the historical homeland. Passover. Some public committee decided to gather the heroes of the aliyah for the first real Seder of their lives at the Western Wall, in Jerusalem. A wonderful idea, but, as always, madly executed—they gathered us from all over the country early in the morning and left us to wait on the bare plaza by the Western Wall until the evening, until the festive Seder. We had to pass the time in the long passages from Jaffa Gate to the Central Bus Station, back and forth, exchanging first impressions of our new lives and still-fresh memories of the swift exodus from our prehistoric homeland. It was a kind of leisurely stroll through a pre-holiday Jerusalem falling quiet, accompanied by the same unhurried and noncommittal chatter. And then suddenly, at some point, Ben (Itsyk Koifman)—there were three of us: Ben, Tolik Gerenrot, and I—suddenly stops and, addressing no one, raises his eyes to the sky: “Lord, just listen to him! Someday this creep is going to write his memoirs!.. Can you imagine what he’ll write about us?!..” We laughed and walked on. But that scene has remained in my memory—indeed, every time, it turns out that I remember everything differently from others. Is that a good thing? A bad thing? I don’t know. But that’s a factual fact for you. I have no need to argue with the world, but every time someone starts with “And do you remember?..,” it all ends very, very sadly. And that is why my hand will not rise to write some worthy and consistent “tale of bygone years”—instead, what flows from my pen are random, fragmented pieces. Just like this time, on the occasion of the memorial days for Babyn Yar.

Fragment One—August 1961

Babyn Yar... I was supposed to be lying there with the others. But my mother worked as an electrical engineer at the Darnytsia Silk Factory, and she was evacuated along with the plant’s equipment and workers. We returned to Kyiv in the summer of 1944. That same autumn, I went to school. Then came the institute, then I left for a job in the city of Stalinsk, Kemerovo Oblast. From there, in August 1961, I came home on vacation to Kyiv. It was then that I attended Yevtushenko’s evening at the October Palace, where he first read his poems about Babyn Yar.

My impression of these poems immediately diverged from the opinions of those around me, even back then. (I may return to this. I would not want to project my present understanding of things onto that time. But that Yevtushenko’s “Babyn Yar” caused an allergic reaction and protest in me from the very evening I first heard it is an actual and indisputable fact).

However, I owe one thing to this day to Yevtushenko and his Kyiv poems—he awakened in me the understanding that the responsibility for everything happening to me and around me—with Babyn Yar, with the Jewish people, with my Jewishness, and with everything in one way or another connected to these things—that responsibility was now on me. Not someone else, but me, precisely me—perhaps the last Jew on earth whom these things still concerned. (So it seemed to me, so I understood and felt it then). But what should follow from this? What could and should be done next? I had no answer to these questions. And so I took my camera and went to do what seemed to me at that moment to be the only possible and natural thing—to document what was happening.

I already knew then about the Warsaw Ghetto, about the brutal suppression of the ghetto uprising in April 1943. I knew that everything we know today about the Warsaw Ghetto is the work of Emmanuel Ringelblum (and his comrades-in-assistance), who collected and left for posterity (in metal boxes and milk cans) the chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto. On the eve of the uprising, they were buried in several secret locations. Neither Ringelblum nor his assistants survived the uprising. But in 1946, while clearing the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, ten boxes of the Ringelblum archive were found, and in 1950, two milk cans were also discovered (the third can, whose existence was also known, was never found).

I knew all of this in August 1961. So I took a camera and went to photograph Babyn Yar after the Kurenivka tragedy of 1961. And next to Babyn Yar, literally adjacent to it (or above it), was the old Jewish Cemetery. Ruined and looted, it made an impression no less horrifying than Babyn Yar—plowed and churned up by land-moving machines that were shifting and leveling heaps of clay, sand, and human bones breaking through this morass.

Below are a few photographs taken then, in August 1961 (source [1]).

In the background of both photographs are new buildings along the Ring Road (today Olena Teliha Street), laid over the northern edge of the filled and plowed-over Yar. If you look closely—at the feet of the people in the first picture (Photo 1) and in the lower right corner of the second—you can see elements of a skull and individual human bones (Photo 2).

Photo 1. Babyn Yar, August 1961, view from the Jewish Cemetery. [1]

Photo 2. Babyn Yar, August 1961, general view of the work area. [1]

But the true picture (a churned-up mess of human bones and soil) the camera, of course, was unable to convey. Therefore, for greater clarity, I had to resort to the method of socialist realism—the bones, extracted from the soil, were laid on top of a caterpillar track (Photo 3). Implausible, but expressive and clear. The result—not a photographic document, but a symbol. That is exactly how this photograph was later perceived (for example, by the organizers of the Second Brussels Conference in defense of Soviet Jewry in 1976—it hung above the entrance to one of their conference halls).

Photo 3. Socialist Realism, 1961. [1]

And above Babyn Yar, and slightly higher than it, were the remains of the Jewish Cemetery of the city of Kyiv. Its destruction began under the Germans, who used the grates and fences from graves as fire grates for the bonfires on which the bodies of those shot in Babyn Yar were burned (the Germans, as they retreated, tried to cover up the traces of what happened there). Under Soviet rule, it was not restored. (Photo 4).

Photo 4. The destroyed Jewish Cemetery. August 1961. [1]

Sometime in the late 60s, all interested parties were invited to transfer the graves they knew of to the new Berkovetske cemetery, but there were very few such people. Most of the unclaimed graves were cleared by bulldozers and the site was leveled for future construction (Photo 5).

Photo 5. Most of the unclaimed graves were leveled by bulldozers,

the headstones were piled up. [1]

However, let’s return to our topic—we are talking about August 1961. Here is how other eyewitnesses and contemporaries of those events describe all this today (or, let’s say, in the post-Soviet era).

Let’s start with Yevtushenko’s own recollections (published in January 2011, [2]):

“Even before my arrival in Kyiv, I was at the construction of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant and met a young writer there, Anatoly Kuznetsov, who worked for the company newspaper. He told me about Babyn Yar in great detail. ... I told him that I was about to go to Kyiv and asked him to come there so he could take me to Babyn Yar. When we arrived there, I was absolutely shocked by what I saw. I knew there was no monument there, but I expected to see some kind of memorial sign or a well-kept place. And suddenly I saw the most ordinary garbage dump, which had been turned into a sandwich of foul-smelling refuse... Before our very eyes, trucks drove up and dumped more and more piles of garbage onto the place where these victims lay....”

Other, earlier recollections of Yevgeny Alexandrovich reproduce this same text with small and insignificant variations [3], [4], [5], [6]. (Although these same events, described in his “Autobiography” in 1969, differ somewhat from their later account. But I do not have the “Autobiography” at hand, and so I will not elaborate much on this matter).

Nevertheless, Vitaly Korotich (the legendary editor of “Ogonyok” during the years of perestroika) remembers these same events quite differently [7]:

“...We met Yevgeny Yevtushenko in Kyiv in the summer of 1961, when he came to my home with the Kyiv literary critic Ivan Dzyuba.

...It was precisely during Yevtushenko’s stay in Kyiv that the dam burst, which the Kyiv authorities had created to silt up Babyn Yar, leveling the ground over it and creating a series of sports grounds on the site of mass murders and burials.

...Yevtushenko asked to be taken as close as possible to the site of the tragedy, and I, as much as I could, led him through the cordons, and then decided that he didn’t need to see the pieces of human bodies being turned up by the excavator from the mud. He had seen enough as it was and right then wrote one of his most famous poems, ‘Babyn Yar.’”

Some people who knew Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov very well assert that it was he, Nekrasov, who brought Yevtushenko to Babyn Yar then (in August 1961). (See the memoirs of film director Rafail Nakhmanovich [8] and Valentyna Bondarovska [9]).

I am not going to sort out here who remembers what now and how. I stand by my own version—in August 1961, Babyn Yar looked as it is captured in my photographs. As for all the rest—“...Well, you have your say, too!...”

Fragment Two—September 1966

The year 1966 is marked in the popular memory as the year of the first mass protest against the violence being committed upon Babyn Yar. Popular rumor has attributed, and continues to attribute, the conception and organization of this historic event to Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov.

“In the autumn of 1966, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the shooting of Jews in Babyn Yar, Nekrasov decided to mark this date with a rally—naturally, an unauthorized one—and invited several people from Moscow, including Vladimir Kornilov.” [10].

“On September 29, 1966, an event unsanctioned by the authorities took place in Babyn Yar, which grew into a spontaneous rally; surviving witnesses of the fascist shooting of Jews spoke. Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov also takes the podium. He knows more than others about the post-war fate of Babyn Yar. And he speaks directly, bitterly, desperately. This speech became the last straw that broke the authorities’ patience...” [11].

“He was collecting materials for a book about this tragedy of the Jewish people. He wrote about it in articles, books, in official letters addressed to Party bodies. He was the organizer of the legendary rally in Babyn Yar in 1966, timed to the 25th anniversary of the tragedy, at which, besides himself, Ukrainian writers I. Dzyuba, B. Antonenko-Davydovych, and others spoke. This rally marked a new stage in the struggle for the commemoration of the victims of Babyn Yar. At Nekrasov’s invitation, his friends, writers and human rights activists—V. Voinovich, F. Svetov, P. Yakir—came to the rally from Moscow. A group of Ukrainian filmmakers led by H. Sniehiriev and R. Nakhmanovich filmed the rally.” [12].

“And now—the main thing: a recollection of how Kyiv’s community, for the first time with such a large-scale public action (unsanctioned!), reminded the authorities that it is indecent and criminal to forget—this is from the memoirs of Ivan Mykhailovych Dzyuba, [13]—...In the last ten days of September 1966, Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov passed a note to me through common acquaintances, in which he asked me to come see him in the first half of the day on the 29th. I, of course, guessed what it was about. After all, September 29th was a special day in the lives of many Kyivans. ... At the appointed hour, I was at Viktor Platonovich’s apartment. I found him with his friends from the Kyiv documentary film studio. Together with the writer Geliy Sniehiriev, they were preparing to shoot a documentary film: it was expected that there would be more people than usual and, if not banned or dispersed, the event would be given a ritual character.

...The people were silent. But it was a demanding, questioning silence. People wanted to listen, to hear something important. But from whom? And when the rumor spread that ‘the writers have arrived,’ they rushed towards us, pulling each of us in different directions (we were also joined by Borys Dmytrovych Antonenko-Davydovych, who came on his own initiative), they surrounded us in a tight crowd and demanded: ‘Say something, at least.’ We had to improvise—although we were talking about something long-suffered and deeply felt. Someone recorded the speeches on a tape recorder, and a few days later they appeared in samizdat, which was then taking its first steps. And, of course, the ‘relevant authorities’ once again showed all their ‘vigilance’ and ‘militancy,’ undertaking ‘educational’ and administrative measures against the offenders. The first victims were the film studio employees—the film they shot was confiscated, and they themselves suffered administrative penalties. And my speech was added to the ‘criminal file’ that had already been gathered on me at the KGB—it later figured in the indictment against me as one piece of evidence of anti-Soviet activity.” [13].

“...September 28, 1966. At Viktor Nekrasov’s, the phone is busy all day. The writer was calling—and talking with cultural figures: critic Ivan Dzyuba, directors Rafa Nakhmanovich, Geliy Sniehiriev, surgeon Amosov, aircraft designer Oleg Antonov, sculptor Valya Seliber. In the evening, they went to Babyn Yar. On the brick wall of the Jewish cemetery, a poster-announcement was fixed in Russian and Jewish: ‘1941–1966,’—and an invitation to participate in a memorial rally—on September 29. ‘There were about twenty people... The moon was in my shot...’—recalls the cameraman.

At sunrise on September 29, people began to trickle through the streets of the City, alone and in groups. They walked the entire path through the streets of the City to the site of the tragedy.

By nine in the morning, about a thousand people had gathered in the wasteland where the television center and sports complex now stand. Documentary filmmakers arrived. They filmed general shots, not yet approaching the group of people who were crowding around a small rise where Ivan Dzyuba, Viktor Nekrasov... were speaking. Around half past nine, a whisper rippled through the crowd: ‘They’re already here!.. A lot of them... Writing down license plate numbers... Making lists....’ A man appeared near the documentarians: ‘Who’s in charge?’ ‘I am,’ replied director Nakhmanovich. ‘Your identification.’ ‘And yours?’ The colonel opened a small book—cameraman Eduard Timlin closed the lens. The counter read barely eighty meters...

In 1989-91, while making a film about Viktor Nekrasov, in search of photo and film documents in Kyiv, Paris, Stalingrad, Leningrad, Madrid, Mexico, and again in Moscow and Kyiv, those 80 meters were never found...” (From the memoirs of Ada Rybachuk [14]).

Despite the abundance of testimonies and recorded personal memoirs, the overall picture remains somewhat contradictory and hazy. In particular, Ada Rybachuk’s statement that “those 80 meters were never found.” As is known, in 1992, the Berlin studio ZDF released a television film by A. Rodnyansky, “Farewell, USSR. Film I. Personal,” [15]. Some part of these 80 meters (and perhaps all of them) was used in this film. This means that even before this, these 80 meters had been found and successfully identified somewhere. (The film itself, one must assume, was made even earlier, since it had already managed to win the Grand Prix for best documentary at the Duisburg German Film Festival in 1992, the same year a Special Prize at the Nyon International Documentary Film Festival and the Silver Centaur Prize at the “Message to Man” International Film Festival in 1993).

In that same year, 1992, another television film by R. Nakhmanovich and E. Timlin, “Viktor Nekrasov on ‘Svoboda’ and at Home” [16], was released, which also used a significant portion of these 80 meters.

In May 2011, for the 100th anniversary of Viktor Platonovich’s birth, the film “Viktor Nekrasov, a Whole Life in the Trenches” [17] was released on Russian television screens. It also contains parts of these same 80 meters.

And just recently, in July 2011, for the 80th birthday of Ivan Mykhailovych Dzyuba, the public could once again see these same shots in the documentary film “Conscience. The Phenomenon of Ivan Dzyuba” [18], prepared by the Dovzhenko studio to honor the jubilee.

All of this, of course, is very illustrative and convincing: The widely circulated documentary footage, filmed at that very time in that very place, the numerous quotes from the memoirs of contemporaries of that first rally. It is all remembered, of course, through the prism of past decades, and therefore some aberrations of memory and inconsistencies in the telling seem quite explainable and excusable. You, of course, have not forgotten that for almost 25 years after this event (until 1991, until the collapse of the Soviet) , any public mention of Babyn Yar was simply unthinkable. Only after many decades did public opinion begin to make the first serious attempts to reconstruct the true course of those events, thereby paying tribute to a phenomenon that undoubtedly played an exceptional role in the personal life of everyone who touched the fate of Babyn Yar then, an exceptional role in the life of a whole generation (of Soviet people) who became willing or unwilling participants in the History they were creating in those days.

I realize that History is not at all what really happened, but a myth, a tale that people like and want to tell each other. I understand and know this perfectly well. And I am aware of the futility of any attempts to resist this established order of things. Nevertheless, I calmly and persistently say to myself and to you: “It wasnt like that at all! It was—very different!”

Without refuting or disputing the stories of others, I tried back in 2006 to present my own account of the events of September of that year (1966). It was published in a supplement to the newspaper “Vesti” (“Okna,” September 28, 2006), and then reproduced on an internet site [19], [20]. However, this publication attracted no attention, and no reaction followed. I will not repeat here what has already been described once. But for the coherence of the narrative, I will reproduce (and clarify) a few key points.

In the first half of the 1960s, having awoken from the Hitlerite and Stalinist pogrom, a new generation of Soviet people—a generation of new Soviet Jews—began to enter their conscious lives and to spin their own cycle of recent (Jewish) history. Like fresh green shoots on the site of black ashes left after the recent universal fire, scattered groups of Jewish youth emerged here and there, concerned with their national identity, which by that time had been destroyed and trampled by the Soviet authorities. (Like Babyn Yar itself in those years, like the countless other mass graves left after World War II throughout the European part of the Soviet ). The realization of their continuity, the acceptance of responsibility for the oblivion and the shameful, humiliating state in which these graves were, was the first step on the path of these young people’s national self-identification and their acquisition of national self-awareness.

For future historians, it would be interesting to note here that this process was spontaneous, independent, and occurred almost simultaneously throughout the Soviet . In 1963, young Jews in Riga began to clean up the site of mass shootings in Rumbula, and in 1964 they erected a homemade plywood monument there [21]. A view of this monument is shown in Photo 6.

In 1966, the first memorial rally was held on the territory of the 9th Fort in Kaunas [22]. In 1969—in Minsk [23].

Photo 6. The plywood monument erected in Rumbula in 1964. [1]

In September 1966, the first rally in memory of Babyn Yar also took place in Kyiv. Which is, in fact, what this is about.

Here is how the beginning of this story looked in the memoirs of Rafail Aronovich Nakhmanovich, a director at the Kyiv Documentary Film Studio ([8]):

“A friend of my wife’s came to us and told us that some young Jewish guys were planning to commemorate the anniversary of the shooting in Babyn Yar. The next day, I asked her to put me in touch with the initiator of this matter. There were several of them, but the main instigator was one guy... I’ll say more about him later... Well, the first thing I did was go to Nekrasov, Viktor Platonovich, and tell him about it. He, of course, got fired up, as this theme—of what the Soviet government was doing in Babyn Yar—deeply concerned him.”

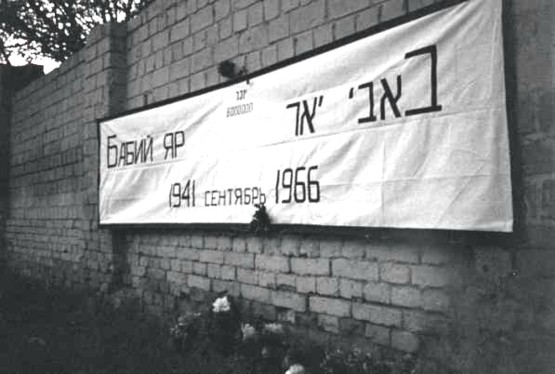

From our side, it looked a bit different: on September 24, 1966, the 25th anniversary of the shootings in Babyn Yar, we hung a banner on the surviving wall of the destroyed Jewish cemetery, located above Babyn Yar (Photo 7). You ask: “Why September 24th?” Because, although we were abysmally illiterate in national matters, we knew that Jewish dates should be observed according to the Jewish calendar (as they are observed throughout the world now, and above all, in Israel). The Nazis began their action in Babyn Yar on the eve of the Day of Atonement (the Jewish Yom Kippur). In 1941—that was September 29, in 1966—the 24th.

We announced to everyone we could possibly reach at the time that at the appointed hour we would be at the entrance to the old Jewish cemetery, and we asked everyone to join us.

And people came. By five in the evening, as agreed, about fifty or sixty people had gathered at the cemetery entrance (no one counted them then). But we, of course, did not expect such a “turnout”!

Our poster was a surprise to everyone (Photo 7). In Russian and Jewish languages, it was written there (in large letters): “Babyn Yar,” below, smaller: “September 1941-1966,” and above, in the center, very small: “Yizkor (in Hebrew—remember) 6 million.” People saw it for the first time. It correctly designated and made the meaning of the event understandable: the place was right by the road, and passengers of passing buses and trolleybuses could easily read what was written—and it was immediately clear to everyone why people had gathered in this usually deserted place (Photo 8).

Photo 7. The banner on the wall of the old Jewish Cemetery, 09/24/66.

And this is how it all looked then (see Photo 8 again): the people gathered, trolleybuses rushed along the nearby road, people from them gawked at us and read the “inscription on the wall.” And nothing more. Time passed, and we didn’t know what to do next. We hadn’t thought it through. And improvising on the spot was both unwise and inappropriate.

Photo 8. The first crowd at the entrance to the old Jewish Cemetery.

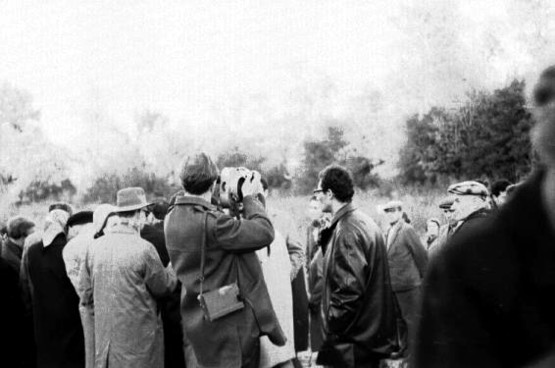

And suddenly, two passenger cars pull up. People with film equipment get out and immediately get to work—they advance on us with movie cameras! At that point, it became clear to everyone—the KGB has arrived to film and record us!

Surprisingly, they did their job with amazing dexterity—quickly and accurately picking out of the crowd precisely those who should be recorded first. And so it remained on their film: Here is Garik Goldovsky (the one on the left, in Photo 9). And here is Garik (Gdalia) Zhurabovich (Photo 10). Here is a close-up of Grisha Pipko (Photo 11). And here I am myself (Photo 12), (with a group of comrades).

Photos 9-10. Garik Zhurabovich (center); Garik Goldovsky (left in the picture).

Photo 11. Grisha Pipko (center); Photo 12. Amik Diamant (center).

Under the aim of the cameras, the crowd began to quickly disperse, and very soon there were only about fifteen of us left. We stood there, huddling together forlornly (Photo 13).

Photo 13. Standing, huddling together in doom.

And then a stranger suddenly squeezes into this group and, extending his hand to me, says: “I’m Nekrasov.” (Mute scene... We didn’t need an explanation of who Nekrasov was. But what he looked like in real life? None of us had a clue. Photo 14).

Photo 14. Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov, 09/24/1966.

Apparently, he had been here earlier (Photo 15), but due to our ignorance and lack of understanding, he went unnoticed and unrecognized. (But this is, so to speak, a note in parentheses. We will continue from here).

.

Photo 15. Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov, 09/24/1966.

(Photos 7-15 courtesy of E. L. Timlin, Kyiv)

Confused, we did not react to his words at all. Not waiting for an answer, Nekrasov, turning to me and nodding towards the banner, asked tersely:

“Did you do this?”

“No,” I replied just as briefly.

“Are you afraid?”

“Yes,” I answered monosyllabically.

The conversation wasn’t going anywhere—it was hardly the time for confessions. Nekrasov tried again to engage those present:

“Why today?”

“Because according to the Jewish calendar, it is today.”

And again a pause ensued. Nekrasov suddenly, as if saying goodbye, extended his hand to me. I felt a note in his hand: “This is my phone number. Call me. We need to talk.” He stepped out of the circle and left. We also dispersed immediately.

Of course, the very next day I called him, and we met. One thing was clear: it was not too late, and we needed to organize another, subsequent “round”—on September 29 of the same year. We quickly discussed all the details. The 29th fell on a Saturday, but we decided to keep the gathering time the same—5 p.m. Two hours until dark, we wouldn’t need more.

Viktor Platonovich was very troubled by the sad experience of our silent vigil, and he kept returning to this topic.

“We should think of something. The action should develop around some ‘center of attention’...”

Finally, he suggested:

“We need to put up a monument. Any kind. Even a temporary one, a wooden one, a plywood one, anything, but a monument.”

According to Nekrasov, his friends Ada Rybachuk and Volodia Melnychenko would agree to make such a plywood monument. They didn’t have much time, but it could be done.

The question of a suitable inscription immediately arose. Viktor Platonovich entrusted the Jewish version to me. I, not daring to take on such a responsibility, immediately rushed to the Kyiv Jewish writers for help. Hryhoriy Polianker listened to me and politely showed me the door. Itsik Kipnis, after much persuasion, agreed and wrote the necessary text. (Like all Jewish writers of that generation, Polianker and Kipnis had by that time already undergone re-education in the Karaganda camps (Kipnis) and in Vorkuta, that is, in Inta (Polianker). Although in 1949 Polianker denounced Kipnis, who had already been arrested by then, he himself was imprisoned in 1951. But he was released much earlier (in 1954) and rehabilitated (in 1955) [24], [25]. Kipnis, however, was only medically discharged on December 30, 1955, and rehabilitated only in 1957).

I calligraphically transcribed the text written by Kipnis. Its main Jewish version and its Russian and Ukrainian translations. As agreed, I took all this to Viktor Platonovich.

And while all these preparations were underway, the word was passed around the city: “Come to Babyn Yar. September 29th. Nekrasov will be there.” The name Nekrasov sounded like a password, like a call. Besides, our banner on the wall of the Jewish cemetery had been hanging for several days already, and no one took it down! For three days, passing by on their way to and from work in the morning and evening, the residents of the Shevchenkivskyi district could see it and read it, like an advertisement. All this together gave the rumors a semblance of clear legitimacy.

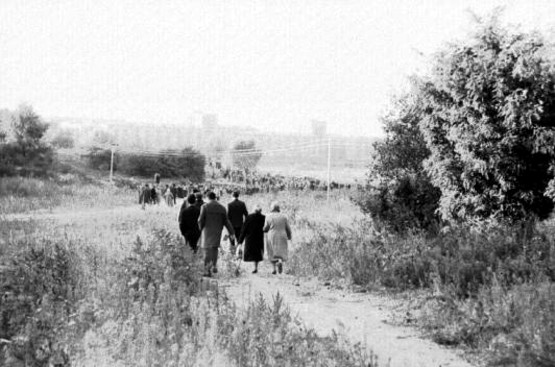

Photo 16. 09/29/66, by 5 p.m., people began to stream to Babyn Yar. [1]

On September 29, by 5 p.m., people began to stream to Babyn Yar (Photo 16). With difficulty, I managed to find Nekrasov in the crowd:

“And where is the monument?”

“There isn’t one and there won’t be...” he answered briefly.

I didn’t press him. Viktor Platonovich, as always, was somewhat drunk, and so any clarification about where and how the breakdown in our agreements had occurred was useless and pointless. (Viktor Platonovich, as is known, was a great specialist in this area. Even informants from the state security reported to their superiors: Nekrasov asserts that ‘The Soviet is a vile country... Against this background, drunkenness is its best flaw.’ [26]).

“We should gather a couple of stones to stand on to be a bit higher,” suggested Viktor Platonovich. But there were no stones to be found. Then Nekrasov and those with him moved slightly up the slope, and Viktor Platonovich began to speak. He spoke very quietly, simply, even matter-of-factly. There were no microphones or amplifiers, so only those who stood literally right next to him heard every word. He wrote down his speech much later, already in emigration. Therefore, its initial text is lost forever, and all that remains in the popular memory is the impression of it, which everyone has shared (and still shares) with others for many years. Fragments of this speech were later included in his books “Notes of a Gaper” (“Continent,” No. 4, 1975) and “A Look and Something” (“Continent,” No. 12-13, 1977).

Photo 17. Viktor Nekrasov and Ivan Dzyuba at the rally on 09/29/66. [1]

After Nekrasov, Ivan Dzyuba spoke. At that time, this name meant little to anyone. Only a few had read the samizdat version of his bold work “Internationalism or Russification?,” which he had sent to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine in 1965. Very few managed to hear Dzyuba’s live speech in Babyn Yar that day. But he wrote down his speech, and it soon appeared in samizdat. Therefore, I can reproduce some of its fragments not from memory:

“There are things, there are tragedies, before whose immensity any word is powerless and about which silence—the great silence of thousands of people—will say more. Perhaps we, too, should have done without words here and thought silently about the same thing. However, silence speaks volumes where everything that can be said has already been said. But when far from everything has been said, when nothing has yet been said—then silence becomes an accomplice to untruth and unfreedom.

...Babyn Yar is a tragedy of all humanity, but it happened on Ukrainian soil. And therefore, a Ukrainian has no right to forget it, just as a Jew does not. Babyn Yar is our common tragedy, a tragedy primarily of the Jewish and Ukrainian peoples.

...But we must not forget that fascism does not begin with Babyn Yar, nor is it exhausted by it. Fascism begins with disrespect for the individual, and it ends with the destruction of the individual, the destruction of peoples—and not necessarily only such destruction as in Babyn Yar.” [13].

No one had ever spoken such words in Babyn Yar before. And very few heard them. But they echoed through all the subsequent decades. And at that moment—the very presence of so many people who dared to come to Babyn Yar on this day and take part in this clearly anti-Soviet parade, to listen intently to these words and to be in this place at this hour—all this meant the highest degree of civil disobedience, of finding one’s own face and worldview. People today can hardly imagine what it meant in 1966 to decide to come to Babyn Yar (clearly having conspired and agreed in advance, clearly organized, although everyone later insisted that it was a spontaneous, impromptu gathering). Here is a fragment from the memoirs of one of those who did not come to Babyn Yar then:

“I knew the rally would happen, I was troubled by the memory of those hundreds of thousands of innocent people, but, obeying a ‘cowardly’ instinct, I did not go. I found an excuse for myself instantly: small children. But Leib, who was formally my senior architect in the group, of course, went.” [27].

Photo 18. The public at the rally on 09/29/66. [1]

The crowd “huddled together” as best it could, and spontaneous orators appeared here and there—spontaneously, spontaneously, uncontrollably. Some claimed that “After Dzyuba, the writer Antonenko-Davydovych spoke, who had been imprisoned in the camps under Stalin for Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism. Antonenko-Davydovych told how a group of Ukrainian writers had managed to get the anti-Semitic book by Kichko, ‘Judaism Unadorned,’ banned.” [28].

Photo 19. The public at the rally on 09/29/66. [1]

Others just as authoritatively claimed the opposite: “Regarding Antonenko-Davydovych, I want to say that he did not speak at Babyn Yar.” [29].

But the photographic film preserved the “speech” of Dina Pronicheva—one of the few who managed to escape from Babyn Yar (Photo 20). And here it would not occur to anyone to dispute the claim that Dina Pronicheva did speak (in a circle of people ready to listen to her) on September 29, 1966. (Although no one ever remembered this later. Except Anatoly Kuznetsov in the revised, published-abroad version of “Babyn Yar”).

Photo 20. Dina Pronicheva at the rally on 09/29/66. [1]

If you go back and look closely at Photo 19, you will see a young man rising above the people (in the far background), and perhaps also saying something. Perhaps this is how Leonid Belotserkovsky, an architect from the Republican Office of Geological Surveying Works, looked, whom our camera missed, but for some reason the vigilant authorities noticed, and who later had all sorts of troubles because of it (at his place of work) [27].

As for us, God had mercy, and we did not figure in this story. In Hebrew, they say: “The deeds of the righteous are done by the hands of others.” We were not great saints, but that time it turned out exactly so.

Fragment Three—It’s Not Over Yet (1966)

Undoubtedly, Babyn Yar 1966 was a fundamental, foundational event in the life of a whole generation of Soviet people (of those years, of that time, and for many years to come). It is no accident that memories of it become a mandatory part of any ceremony timed to the anniversary of those whom fate once linked with Babyn Yar.

The film for the 100th anniversary of Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov (like any other remembrance of him) necessarily contains a mention of Babyn Yar and his participation in the 1966 rally. The film for the 80th anniversary of Ivan Mykhailovych Dzyuba (and other, earlier publications of his) also contain recollections of his speech in Babyn Yar. Any other citizens—they, too, now recall this everywhere. But all of this, as mentioned above, is post-factum, reflections on events of a time long past. And people’s memory is imperfect, and people see everything, even if they are looking at the same things, completely differently.

In these conditions, photo and film documents are perhaps the most reliable and objective evidence. Although, of course, they also require close examination and reliable commentary. For example, when showing Nekrasov at the rally he organized in Babyn Yar, no one for some reason asks or explains to the viewer where Viktor Platonovich got such knowledge of the Jewish language, which adorned the banner hung on the wall of the Jewish cemetery. (But that, as they say, is by the way).

Besides photo and film documents, the most reliable and noteworthy evidence may be testimonies recorded directly or in a time relatively close to the actual events. For understandable reasons, I, although I remembered the feat of Emanuel Ringelblum (who created and preserved the archive of the Warsaw Ghetto for posterity), could not follow his example (although I tried as best I could)—in the conditions of the USSR, minimal safety rules excluded the keeping of any archival records. But the world is not without good people—after the collapse of the Soviet , the archives of Soviet institutions opened up, and some archival records of other direct participants in those events suddenly became accessible to all interested parties. I, naturally, belong to these very “interested parties,” and in this regard, I also want to tell you something.

The events in Babyn Yar took place on September 24-29, 1966. And as early as October 1, 1966, the secretary of the Kyiv City Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, O. Botvin, reported to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (and personally to Comrade Shelest P.E., the First Secretary of the CC CPU) “On the incident of holding an unorganized rally at the site of the shooting of Soviet people by the German-fascist occupiers in Babyn Yar” [30]. (The Jewish department of the 5th Directorate of the KGB is not even on the horizon yet; the 5th Department will be created from the 2nd department of the 2nd Directorate only in July 1967, and the 5th Directorate of the KGB only in 1979, [32]. Therefore, the Communist Party itself has to deal with all particularly important matters of this kind).

On October 12, 1966, the bureau of the Kyiv City Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine promptly and on the heels of the event discusses the same issue—“On the incident of an unauthorized gathering in Babyn Yar,” [29]. (At the city committee bureau, the “unorganized rally” is already called by a more accurate and familiar name—“unauthorized gathering,” [31]).

Sometime between October 1st and 12th, a letter from Comrade Shelest with a report to the CPSU Central Committee about the events in Babyn Yar was sent to Moscow. (I do not provide, as usual, references to this document here, as I do not have this reference at hand right now, but I have held a copy of this document and I dare say that it literally repeats the text of O. Botvin’s letter. Only Botvin’s text is in Ukrainian, and Shelest’s is in Russian. Incidentally, it is interesting to note that the text of Protocol No. 31 of the meeting of the Kyiv City Committee Bureau of the CPU, [31]—is also in Russian (!?!). What could this mean?).

Why do I scrutinize these documents so meticulously? First of all, because the level of discussion speaks to the exceptional importance that the discussants themselves attached to this event. Secondly, some discrepancies in the texts allow one to judge the hidden intentions and designs of their authors—the text to Moscow must reflect a deep knowledge of the subject and complete control over the situation. The text for internal discussion (at the bureau) is more accurate, with less puffing of cheeks, fewer fabricated details.

For example, it is reported to Moscow that “those present were expecting the arrival of representatives of local authorities, as well as the writers I. Ehrenburg, V. Nekrasov, and professor-surgeon N. Amosov.” At the bureau, not a word about this.

It is reported to Moscow that “members of the of Writers of Ukraine Nekrasov, Dzyuba, Antonenko-Davydovych, Belotserkovsky spoke before those present.” At the bureau, things are called by their proper names: Nekrasov and Antonenko-Davydovych are writers, Dzyuba is an employee of the Institute of Biochemistry of the Academy of Sciences of the UkrSSR, Belotserkovsky is an architect, an employee of the Republican Office of Geological Surveying Works.

To Moscow—“By order of the Kyiv City Committee of the CPU, the Party committee of the of Writers of Ukraine conducted an investigation into the motives for the appearance and behavior at the unorganized rally on September 29 of the writer-communist Nekrasov, the writers Dzyuba, Antonenko-Davydovych, Belotserkovsky. The Party committee has raised the issue of bringing the aforementioned persons to account before the Presidium of the of Writers of Ukraine.” But among themselves—“The Party organizations of the of Writers (Party bureau secretary, Com. Kozachenko), the Ukrainian Chronicle and Documentary Film Studio (Party bureau secretary, Com. Makoveev), the Institute of Botany of the UkrSSR Academy of Sciences (Party bureau secretary, Com. Pratsiuk), the Institute of Biochemistry of the UkrSSR Academy of Sciences (Party bureau secretary, Com. Kokunin), the Republican Office of Geological Surveying Works (Party bureau secretary, Com. Tankilevich) did not take effective measures...”. And therefore, they are only being urged to “resolutely improve ideological and educational work in the collectives...”.

And here is another discrepancy: It is reported to Moscow how the leadership of the Kyiv synagogue fought against instigators calling for people to go to Babyn Yar on September 29. (I have a copy of this denunciation from the synagogue addressed to the Commissioner for Religious Affairs for Kyiv and Kyiv Oblast). At the city committee bureau, of course, there is no mention of this nonsense. But there is the following message (or more likely, just boasting): “Despite a timely warning (emphasis mine), the Shevchenkivskyi district committee of the CPU (Com. Fursov) did not take mass propaganda measures to prevent the illegal gathering at Babyn Yar.” Well, well, it turns out they knew everything, but for some reason they suddenly (despite) messed up?!.

. But where they really couldnt do anything was in the story with the filmmakers. It turns out that on September 24-29, 1966, two film crews were shooting in Babyn Yar. Here is a long quote from the letters of Botvin-Shelest: “The unauthorized rally in Babyn Yar was filmed by a crew from the Ukrainian Chronicle and Documentary Film Studio consisting of director Nakhmanovich R. and Timlin E. These studio employees used state-owned equipment and film, and also went to the scene of events on their own initiative and filmed without an order or prior instruction from the film studio.

Also working at the rally site was a film crew from ‘Mosnauchfilm’ consisting of the second director of the film ‘In One Family’ (about the life of Jews in the Soviet) , Solomentsev M. G., and cameraman Lunin V. L. As M. G. Solomentsev and the director of the same film, R. Yu. Goldin, explained at the city committee of the CPU, they consider the filming of the unorganized rally in Babyn Yar necessary for the film ‘In One Family.’”

Photo 21. Cameraman V. Lunin filming at the rally on 09/29/66. [1]

The Kyiv Party bosses dealt with their own—the Ukrainian Chronicle and Documentary Film Studio—simply and quickly: “The administration of the Ukrainian Chronicle and Documentary Film Studio imposed a severe administrative penalty on director Nakhmanovich R., cameraman Timlin E. and warned them that if such offenses were repeated, they would be fired from their jobs.

The film footage of the rally has been confiscated. The question of Nakhmanovich’s and Timlin’s behavior will be discussed at a meeting of the studio’s collective.” (For other juicy details of this case, read the memoirs of Rafa Nakhmanovich [33] and Geliy Sniehiriev [34]). In reality, the crackdown at the Kyiv film studio was quite slapdash—everyone was reprimanded, the film was confiscated, but cameraman Timlin managed to hide 80 meters, which were later included (in various configurations) in a whole series of documentary films [15], [16], [17], [18].

But what to do with the Moscow filmmakers, the Kyiv Party bosses, of course, had no idea. Just in case, they reported everything to Moscow, but they themselves were very careful with them. I think they had good reasons for this—after the interrogation at the city committee of the CPU (this is mentioned in the letters) they knew exactly what was happening. But what to do with it, they had no idea. (Thats why, I think, the banner on the wall of the Jewish cemetery hung for three whole days—they obviously thought it was part of a film set).

But in reality, here’s how things stood: In 1966, the founder of Israeli cinema, Margot Klausner, reached an agreement with the Soviet authorities and received permission to make a film about the life of Jews in the Soviet . A group from “Mosnauchfilm” was assigned to help her, and she traveled with them all over the . By a strange coincidence, it was on those very days that they all (led by Margot Klausner) ended up in Babyn Yar.

The film about the Jews of the Soviet , in several versions with different titles, was later released for distribution (after 1967, after the break in relations with Israel). I have seen three versions of this film—one in Kyiv, in 1969. Another in Israel, in 1972 (Israeli television invited me then to comment on this film). A third version—“We Live Here”—I found in the Margot Klausner archive in Israel, in Herzliya. There are several shots of the events of September 24, 1966. In general, the scenes from Babyn Yar in all versions of the film became shorter and shorter over the years. What I saw in Herzliya, they did not let me copy. In Herzliya, the museum does not just hand out its archives to anyone, it only sells them, you know.

Photo 22. A still from the film in the Margot Klausner Herzliya Archive. [1]

In the end, they took pity on me and still made a few photocopies for me, having first disfigured them with marks so that these frames would no longer have any artistic value. (To hell with them, the keepers of the Herzliya archive, I have no need for their artistic value. I am quite satisfied with their priceless historical significance).

Fragment Four—Nationalists

All the documents mentioned above ended with a surprisingly monotonous conclusion: “Based on the foregoing, it can be concluded that the rally on September 29 in the Babyn Yar area was organized by Jewish and Ukrainian nationalists with the aim of inciting nationalist tendencies among the Jewish population of the city of Kyiv.”

Well, Ill be! If Nekrasov and Dzyuba could somehow be called Ukrainian nationalists (the Russian writer V. P. Nekrasov, say!), then in relation to us, the definition of “Jewish nationalists” was clearly an unfounded exaggeration. We, Jewish nationalists?! To be a nationalist, one must at least belong to some nation. Our national identity was completely exhausted by just the 5th point (in our passports). And even that was a clear misunderstanding—after all, according to Stalin’s definition of a nation [35] (and there were no other definitions in circulation in those years), Jews, as a nation, simply did not exist! What kind of nationalists could there be if they lacked even the most elementary signs of a nation? A common language? We had no Jewish language. A problem like “internationalism or Russification,” (as Dzyuba had, for example), simply did not exist for us—the Soviet government had long ago decided everything for us and without us—besides Russian, other languages were unknown to us. (We didn’t even want to know Ukrainian. We have carried our role as imperial Russifiers ever since, valiantly, steadfastly, “through worlds and ages”). Of course, in Soviet conditions, nationalism could exist without a national language—for example, Olzhas Suleimenov’s Kazakh nationalism existed and managed perfectly well without the Kazakh language; everything he needed, he expressed beautifully in Russian.

But he had his own common ancient culture (which was also considered a mandatory sign of a nation), his own akyns, sages and storytellers, philosophers and poets. We were completely deprived of all this as well—the entire flower of Jewish culture had been cut down even before the Doctors Plot. We inherited nothing of their splendor. Another mandatory (according to Stalin) sign of a nation—compact residence in a common territory. But after Hitler and the Catastrophe, this was also gone without a trace. A common economic life? And here, only the collective death sentences in the economic trials of the early 1960s could be credited to us as a nation.

Naked among wolves! That would have been the correct way to characterize us at that historical moment. And the proud definition of “Jewish nationalists” was definitely not about us. But we tried, we learned, we wanted, like others, to be and to seem like people among people. As usual in those glorious years, the main source of our national self-education was what Soviet propaganda itself brought and reviled, the great leader and teacher himself. In his work “Marxism and the National Question,” [33], Comrade Stalin utterly demolished some Otto Bauer and his idealistic assertion that “a nation is a community of fate.” Well, well, that, strangely enough, suited us just fine.

We also learned about the existence of the Jewish national idea—about the Bund or about Zionism—from the same propaganda and its harsh Marxist critique of these false doctrines. (The Bund merged with the RCP(b) in 1919, and in 1937 the Bundists who had “infiltrated the party” were successfully exposed and eliminated. Zionism was outlawed as early as 1925, and those who were not imprisoned in Siberia back then were finished off, tormented, and tortured in 1948). Therefore, the main, fundamental factor of our national self-awareness (our future Jewish nationalism) was, of course, (the only thing left to us) the Jewish graves, scattered everywhere after the war—desecrated, neglected, doomed by the Soviet government to decay and oblivion. A few years later, when the Jewish national movement would acquire some tangible forms (samizdat, circles, poems, songs, and other amateur activities), Itsyk Koifman (better known to the people as Ben Aeroflot) would write: (forgive me, but I am reproducing everything from memory, with flaws):

And we march through (blah-blah-blah) and flame,

Through (blah-blah-blah) and glimmers of fires,

And, like warriors, we kiss our banner—

The kerchief of a girl, shot in Ponary...

Ponary, Rumbula, Babyn Yar—that is what was turning (and, in the end, turned) us into a nation (and, naturally, into Jewish nationalists). It turns out that Renan already knew that “common sufferings unite more than common joys. In matters of national memory, mourning is of greater value than triumph: mourning imposes obligations, mourning incites common efforts” [36].

All the documents cited above contained another remarkable revelation: “The city’s Party and administrative bodies are taking measures to identify the instigators of the said rally and to bring its active participants to justice, as well as to prevent such cases in the future... The Kyiv City Committee of the CPU has obliged the militia to take more decisive measures to prevent and disallow gatherings and processions that have not received prior permission or are held without coordination with local Soviet authorities” [30].

The KGB is not mentioned here (its 5th departments and sub-departments have not yet been created), but the KGB is invisibly present in all these affairs. They have been fighting Ukrainian nationalists for a long time—“...only for the period 1954-1959, the (Committee for State Security under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR reported) the liquidation of 183 nationalist and anti-Soviet organizations and groups, the criminal prosecution of 1879 individuals, and the application of prophylactic measures against 1300 citizens” [37].

“No less ‘effective’ was the activity of the special services in the next four years... During this period, 219 individuals were brought to criminal responsibility under political articles,” (ibid, [37]). “...For the period from 1967 to June 1971, the KGB of Ukraine prophylactically warned over 6000 individuals. At the same time, 87 citizens were brought to criminal responsibility for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (Article 62)...” (ibid, [37]).

But they did not seem to have a “Jewish front” then. In any case, their informers acted very crudely and unprofessionally. Sometime at the end of October 1966, a good acquaintance of mine brought his good acquaintance to me:

“Ryurik Nemirovsky (a great friend of the writer Nekrasov),” he said, “very much wants to help Viktor Platonovich, and at his request is looking for the man who recently organized the rally in Babyn Yar. Do you happen to know such a person?.. And if you find out... You understand, Viktor Platonovich will be very happy....”

I, of course, was ready to immediately help Ryurik Nemirovsky (anything for Viktor Platonovich, of course), but among my acquaintances, of course, I did not know such a person. If I suddenly found out—I would certainly (through our mutual friend) let him know... (And we drank, and we ate, and we drank again, like the best and truest of friends).

But fate, of course, did not present us with such gifts often. Although, as they say, God had mercy for a time. However, what professional informers could not find, many other “interested parties” found very quickly and easily. Immediately after Babyn Yar, we were “contacted” first by one Jewish group, then another, then more and more. Unexpectedly, the circle of “Jewish nationalists” began to expand rapidly.

Ukrainian nationalists, when needed, also found us without much difficulty—in March-April 1967, during preparations for restoration work in one of the temples of the Vydubychi Monastery, they began to remove ownerless books that had been dumped there since the post-war years and forgotten by all. One fine day, some Ukrainian lads brought me a stack of burnt title pages and covers of books with Hebrew letters. It turned out that these were books from the State Jewish Library of Kyiv! (90,000 of whose books the Germans had taken to Germany in 1942. In 1946, the Americans discovered it in their occupation sector and returned it to the Soviet . Sometime around then, it was apparently sent to Kyiv and stored in one of the temples of the Vydubychi Monastery. And now, being of no use, they began to take them out and burn them. And before that, in 1964, the Ukrainian fund of the Public Library of the Academy of Sciences of the UkrSSR was burned).

I again rushed to Polianker—after all, he was then the secretary of the Jewish section of the Ukrainian of Soviet Writers. This time he did not kick me out, but, having sorted through and selected the most impressive “material evidence,” he took it all to Mykola Bazhan, an academician, Hero of Socialist Labor, chief editor of the Ukrainian Encyclopedia, the only available intercessor and defender at that moment. Bazhan was outraged, promised to intervene immediately, and told me to come back to him in a week. But neither in a week, nor in two or three weeks did he get a response from the Central Committee. And at the beginning of June, they announced: “Israel has unleashed aggression against Egypt. It is inappropriate to talk about the fate of Jewish books in these conditions.” And that was it, the whole story of how Ukrainian nationalists wanted to help Jewish nationalists prevent the destruction of the books of the Jewish State Library of the city of Kyiv. They did not succeed—everything was taken out and burned in May 1967.

Fragment Five—Zionists, Forward

The Six-Day War, in which tiny Israel inflicted a crushing defeat on the Hero of the Soviet Gamal Abdel Nasser and his Arab friends with their Soviet patrons, rendered inappropriate many other things and concepts that had previously been considered unshakable. For example, the myth of the USSR’s invincible military might, of the effectiveness of Soviet military aid, of the utility of Soviet military advisers and the latest military technology, which the USSR generously bestowed upon the “progressive regimes” of its allies. Jews walked the streets and, for some unknown reason, smiled at random and quietly rejoiced. And not only Jews—a large part of the Soviet people “with a feeling of deep satisfaction” received the news of the humiliating defeat of the Arab armies and the shameful international failure of their beloved Motherland. However, not only the Soviet people—the whole world was amused and openly rejoiced at the new order of things that had unexpectedly arisen in the world.

The Soviet , of course, could not endure all this quietly and peacefully. A deafening propaganda howl began, directed primarily against the spawn of all misfortunes and woes on earth—against the Israeli aggressors and agents of international Zionism. Once, in 1948, when the newly created (with Stalin’s blessing) State of Israel suddenly refused to become a vassal of the Great Helmsman, he responded with such a spree of antisemitism and anti-Zionism (throughout Eastern Europe) that the world had not seen since the times of the Spanish Inquisition. According to the same Jesuitical laws, in 1967, an anti-Zionist (i.e., antisemitic) campaign of unprecedented scope began. Neither the Soviet people nor the Jews themselves could be surprised by this—the concept of “Jew” had long ceased to exist in the Soviet lexicon. It was replaced by countless euphemisms—“killer doctors,” “cosmopolitans,” “agents of the Joint.” Now, “Zionist aggressors” were added to this. So what? Who was actually meant here—Soviet people needed no explanation. And without any explanations, everything was perfectly clear to everyone.

It seems it was becoming clear to Soviet Jews as well. One fine day (and by no means of their own choosing), the still-fledgling “Jewish nationalists” turned into “Israeli aggressors,” “agents of Zionism,” or simply “Zionist hawks” (of local scale). No Bundist talk of national and cultural autonomy, no promised brotherhood of peoples and their own national culture (“national in form and socialist in content”), no “coexistence of fraternal peoples,” nothing! Except for the one thing that the Soviet government had prepared and laid out for us—to become a newly minted and blatant Zionist! (Or, as a choice, to become a rootless, nationless sycophant. Quietly and forever). We accepted the alternative offered to us—and began to quickly try Zionism on for size.

This happened surprisingly painlessly and easily—we had no past burden (no Jewish bourgeois nationalism) behind us. No past cultural and historical attributes of national existence weighed us down. Well, nothing, absolutely nothing. Except for one thing—except for Babyn Yar. But that was already like a birthmark—you couldn’t powder it, or burn it out, or erase it—it was with us forever.

The tale is told quickly—but in reality, all this happened much more slowly and painfully. No special events were planned for Babyn Yar in 1967. The public came, but unorganized, wandering around the area where the “unauthorized gathering” had taken place the previous year. The stone that the authorities had hastily installed back in October 1966 (immediately after the “unauthorized rally”) was placed to the side, across the road from the site of the previous year’s gathering, and so many simply did not know about it. Therefore, those who accidentally discovered the stone just loitered around it. And at the same time, others wandered aimlessly on the other side of the road (and therefore could not see the stone from the low ground).

Nevertheless, despite the external disorganization, intense internal work was underway within the “Jewish collective.” The Zionist idea, being embraced by the masses, demanded a revision of all previous speculative constructs and definitions. Painfully, but steadily, an understanding of our new goals and tasks was being developed:

· It is self-evident that the continuation of the natural existence of the Jewish people is possible only in an independent Jewish state, in Israel.

· The building of a Jewish state in Israel and the extraordinary conditions in which this construction is taking place today require the efforts of each and every person who agrees with the point stated above. This means that our place is now in Israel, and the struggle for the right to leave for Israel becomes the main direction of our efforts and our activity.

· Our movement for emigration to Israel must be a mass movement, and therefore it must be legal, public, coordinated, and agreed upon with the Soviet authorities.

· In this regard, our relations with the Ukrainian national movement and the all- democratic movement remain friendly and trusting, but we will no longer fight for a change in the existing system of government in this country; that is not part of our tasks. Our goal is to leave this country and go to our historical homeland, to Israel.

This is approximately how the Zionist program of the Jewish national movement looked at that moment. (Naturally, we did not keep any minutes at that time, and therefore I cannot provide documentary confirmation of these provisions. In one of my previous publications [39] I have already touched on this issue, so I will only quote a few excerpts from Yu. V. Andropov:

“Under the influence of Zionist and anti-communist propaganda from abroad, a tendency towards unification and anti-Soviet actions is observed among Soviet Jews infected with nationalism, under the guise of a struggle for the ‘awakening of national self-awareness’ and the ‘development of Jewish culture’... In 1969-1970, there was a process of gradual unification of illegal Zionist groups and organizations that had emerged in various parts of the country into an underground Zionist party... Through operational and investigative means, it was established that in August 1969, a meeting of representatives of Zionist groups from Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv, Riga, and Tbilisi took place in Moscow, at which an agreement was reached to a so-called ‘All- Coordinating Committee’ (VKK) to coordinate Zionist activity... The Committee for State Security is closely monitoring the negative processes taking place among the Jewish intelligentsia and youth, studying the causes of their emergence, and taking measures to prevent harmful consequences. The focus of the KGB is the work to suppress the hostile, especially organized, activity of Jewish nationalists, with the main method being the decomposition, disunity, and splitting of groups, the discrediting of their inspirers and leaders, and the detachment of misguided individuals from them...”

And another quote (from Andropov):

“The main tasks of the organization are:

- inciting emigration sentiments and persuading Jews to leave for Israel,

- propagating Zionist ideology among persons of Jewish nationality by producing and distributing Zionist and nationalist literature,

- organizing the collection of signatures for an appeal to the UN from persons who have been refused permission to leave for Israel,

- creating courses (‘ulpans’) for the study of the Hebrew language and the education of students in a pro-Israel spirit,

- increasing the financial resources (treasury) of the organization through contributions from its participants and the sale of printed materials.”

I will not review the history of the struggle for emigration to Israel that unfolded—I have already done that once, and so particularly meticulous readers can refer to my previous publications [39]. There, using Israeli documents, I describe and show how this process began and developed. Now that the Kyiv archives have been opened and become accessible, I thought I would supplement this story with new data. But it was not to be—getting to the necessary material, it turns out, is not so simple. I managed to gather only small crumbs. “In the second half of the 1960s, 5,762 Jews living in Ukraine submitted applications for departure” [38] (i.e., I will add myself, almost half of those who were applying for departure throughout the entire Soviet at the same time [39]). Applying, of course, did not mean that it would be followed by permission to leave, and, naturally, no one (or more precisely—very few) received such permission then, but the documented numbers of refusals allow us to judge the scale and dynamics of the process: “If in 1968, 28 Jews were refused the right to emigrate, then in 1969—1,079, in 1970—1,439” (reference to the MVD archive [38]. Although the geography of applications/refusals is not indicated anywhere).

In this atmosphere, the events related to Babyn Yar began to acquire a new, previously unknown coloring. Trying to maintain control over the situation, the Kyiv city authorities decided to take the mourning events in Babyn Yar into their own hands. In 1968, it was first announced that an organized rally of workers would be held in Babyn Yar. At it, the best people of the Shevchenkivskyi district (including Jews) were to decisively expose and condemn the Israeli aggressors and their hirelings (and, if you will, inspirers)—the agents of international Zionism—from a crimson-draped rostrum near the stone. From 1968, this form of conducting mourning ceremonies in Babyn Yar became standard. The proposals of the Kyiv City Committee of the CPU (Comrade O. Botvin), sent on this matter to the CC CPU (Comrade P. Shelest), looked like this: “It is proposed that the rally be opened by the secretary of the city party committee, and that 2-3 participants of the Great Patriotic War (of Jewish nationality), a writer, and the secretary of the city committee of the Komsomol also speak” [40].

Photo 23. Rally of workers of the Shevchenkivskyi district in Babyn Yar [1]

And so it was—the rostrum, the speakers, the officers of various agencies (in uniform and without), and the volunteer police with the militia—look closely at Photo 23, and you will find and see it all there.

What you wont see is what began to happen after the official ceremony. In 1968, when the main, invited part of the public had already dispersed, and only a small group of uninvited Jews remained, wandering aimlessly around the vile pagan altar, Boris Kochubievsky suddenly began to speak. About how it was outrageous to talk about Zionists and Israeli aggressors in Babyn Yar without mentioning that Babyn Yar is the place of death of many thousands of Jews. And specifically Jews. A few do-gooders who happened to be nearby entered into an argument with him, clearly egging him on and provoking him, but he persistently repeated his point.

At the end of November, Kochubievsky’s home was searched, and a week later, on December 4, 1968, he was arrested and charged under Article 187-1 of the Ukrainian Criminal Code [42].

In March 1969, the “Kyiv activists” had to figure out how we should behave in the current situation and how to react to what was happening. Opinions were divided—Zhenya Bukhina and Anatoliy Gerenrot believed it was unacceptable and immoral—in 1969, a Jew is being tried in Kyiv for Zionism, and we are silent. That is, everything is happening without our resolute opposition, that is, with our silent connivance. Alik Feldman and I were against open protests in defense of Kochubievsky. All possible help and support for his family—yes. An open protest in his defense—no. (Because such a protest could yield nothing but exposing ourselves to the authorities. We were already coming out of the underground—invitations from Israel were about to start arriving, the KGB would find out about it even before we did. But to voluntarily expose ourselves and reveal to them “who is who” in our midst—was, in our opinion, senseless frondeurism). Besides, Kochubievsky hardly deserved such self-sacrifice—in the summer of 1968, Gerenrot had already met with him, proposing interaction and cooperation, but Kochubievsky refused. He didn’t want to hear about any interaction or cooperation—he had no need for an article “for organized actions and group activity.”

Coordinated actions have never been our strong suit (neither then nor now). In May 1969, Gerenrot, Bukhina, Koifman, and Ozeriansky testified as defense witnesses at the Kochubievsky trial. These testimonies made no impression on the court, on the KGB public gathered in the hall, or even on Kochubievsky himself (according to his memoirs). “The Chronicle of Current Events” reported on this in sparse words: “On one of the main episodes of the accusation, Babyn Yar, 8 witnesses testified—of them, only three supported the prosecutions position... The court rejected the evidence of the defense witnesses, stating that all these five people are friends of the defendant and fully supported the ‘Zionist views’ of the defendant in court” [43]. (There were not 5 defense witnesses, but 4, but that doesn’t change things. Kochubievsky does not even remember the fact that defense witnesses testified in his favor, he was never interested in it—so he told me during our conversation on June 23, 2011). The Kyiv Jewish community also learned little about this testimony in defense of Kochubievsky).

Fragment Six—A Chronicle of Current Events

In the autumn of 1969, the VKK (All- Coordinating Committee) was created (see above and [39]). The presence of Zionists in Kyiv had also been declared—witnesses at the Kochubievsky trial and the submission of the first applications for emigration in the summer of that year had already happened. For all these reasons, Babyn Yar in 1969 was clearly colored by Zionist presence and Zionist colors. I once described the details of this event [20], and therefore will not repeat myself. I will only quote an excerpt from the correspondence between O. Botvin and P. Shelest on this matter:

“As it has become known to the Kyiv City Committee of the CPU, a certain part of nationalistically-minded citizens of Jewish nationality intends to hold a gathering at Babyn Yar on September 29 of this year, to lay out a six-pointed star with flowers near the memorial stone, and so on. In this connection, it is proposed that on September 29, 1969, at 2 p.m., a rally of representatives of Kyivs working people be held in Babyn Yar, following the example of last year...” and so on [40].

As always, archival documents require commentary. First of all, pay attention to the date of the letter—September 16, 1969. This means that the informers among us worked tirelessly, and the Kyiv authorities knew that on September 29, 1969, a Zionist Star of David was to appear in Babyn Yar. In this regard, they requested permission to take measures to prevent (this). And in the meantime, they reported: “Contacts with the relevant administrative bodies regarding the rally have been established” [40]. What does this mean? It means that on the morning of September 29, not one, but three gray “Volga” cars were waiting for me at the exit of my building. And yet, at 6 p.m. that same day, three young men (Gerenrot, Koifman, and Ozeriansky) brought two large triangles (each side—2 meters), one woven with white flowers, the other with blue, to the stone and unfurled them at the foot of the stone to form a Magen David. A brief scuffle, as some (men in plain clothes) try to move and destroy the triangles, while others (the public present) try to prevent them. In the end, Gerenrot, Koifman, and someone else, a third person (who would later turn out to be a “stool pigeon,” “their man”), are taken away by the authorities, and the public lights pre-prepared candles and stands in silence until dispersed by the militia. In a report [41], the Kyiv City Committee of the CPU reports to the Central Committee on the successfully conducted event. (All this together means that the level of interest in our presence in Babyn Yar continues to be extremely high).

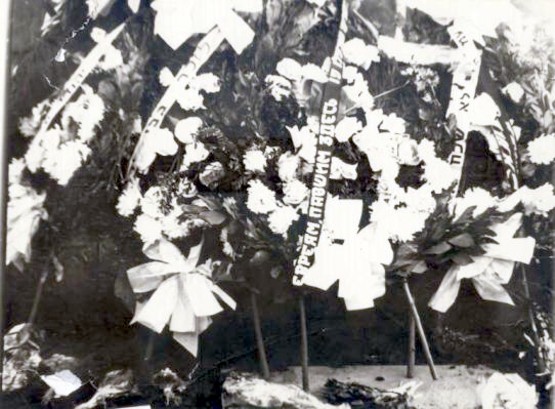

In 1970, the Kyiv public witnessed a new “Zionist provocation” in Babyn Yar—wreaths with Jewish inscriptions in Yiddish and Hebrew were laid at the stone. Again, as in 1969, the authorities knew something about what was to come, but not everything—the scale and organizational forms of what was happening clearly caught them by surprise. (In any case, after 1970, it was never again possible to lay wreaths at the stone in such a format, although such attempts were repeated many times). You can see a fragment of the picture of the laid wreaths in Photo 24.

Photo 24. Wreaths at the stone in Babyn Yar, 1970. [1]

In March 1971, completely unexpectedly for everyone, the exodus of Jews from the Soviet began. Public, permitted, coordinated with the authorities. Departure—by personal, very polite, and very urgent invitation from the relevant state agencies. Inspired by what was happening, the Jewish people rushed to demonstrate their solidarity with their Jewishness—for the memorial ceremony in Babyn Yar that year, 50 representatives from different cities of the came. But the authorities already knew what to do about it: “the KGB men, of whom there were very many that day, got to work. They tore the mourning ribbons from the wreaths. Kippahs were torn from our heads, mourning armbands from our arms... When we approached the final destination, there were no ‘identifying’ Jewish signs either on us or on our wreaths. Everything had been torn off, thrown away, ‘confiscated’”—this is how Yosif Begun (a Muscovite, former activist of the Jewish movement, prisoner of the GULAG) remembers that Babyn Yar [44].

The year 1972 was marked by two decrees, the existence of which Jewish activists knew nothing about, but very soon felt their effects. On February 1, the Central Committee of the CPSU adopted a resolution “On measures to intensify the struggle against the anti-Soviet and anti-communist activities of international Zionism,” and on September 7, 1972, the Secretariat of the CPSU Central Committee approved the “Plan of main propaganda and counter-propaganda measures in connection with the latest anti-Soviet campaign of international Zionism” (quoting from an article by O. Bazhan [45]).

And further, ibid: “Thus, in addition to the already traditional propaganda measures, these party documents contained a number of new elements—the application of repressions to the so-called ‘Jewish nationalists’... ...Active participants in the movement for emigration to Israel were punished not only under political articles. Very often they were charged with criminal offenses” [45].

For Jewish activists, Babyn Yar becomes a symbol of Jewish defiance, Jewish pride, Jewish history, part of a grim Jewish “today” and a future Jewish “tomorrow.” The stone at Babyn Yar becomes a place for Jewish memorial events of the widest spectrum—from religious ritual ceremonies to civil political actions. (In the late 70s and all of the 80s, Babyn Yar even becomes an element of the wedding ceremony—Jewish newlyweds come here to lay flowers and take a commemorative photograph).

In full accordance with these new phenomena—“In 1972, on the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Jews—Krasny B., Rodomyslsky M., Remennik S., Mandel I.—were summoned to the Kyiv city council. In a conversation with them, the city council secretary V. Zernetsky stated that holding a rally in Babyn Yar is prohibited because not only Jews are buried there” [46].

Photo 25. An action at the stone in Babyn Yar, 1972 (most likely, this is the Ninth of Av). [1]

“The Chronicle of Current Events” reported: “On September 7, 1972, a group of Kyiv Jews tried to lay a wreath and flowers at the gravestone in Babyn Yar in memory of the 11 Israeli athletes killed in Munich. The participants of the mourning ceremony were awaited by militia detachments, KGB officers in plain clothes (among them, already long familiar to many Jews, were operational workers of the UKGB for Kyiv Oblast, Smirnov, Bryukhanov, and others, who had more than once participated in various actions against Jews, particularly at the Kyiv synagogue). In addition to militia and KGB cars, there were several oblast committee cars. They detained those who approached with flowers or refused to ‘disperse.’ In total, 27 people were detained, of whom 5 were fined 25 rubles, 11 were sentenced to 15 days of administrative arrest on false testimony, and for each a different ‘corpus delicti’ was invented. Arrested: Yuri Soroko, Basya Soroko (wife), Simcha Remennik, Zinoviy Melamed, Mark Yampolsky, Yuri Tartakovsky, Dmitry Dobrenko, Vladimir Vernikov, Vsevolod Rukhman, David Miretsky, Yan Monastyrsky.

A day before the end of the term, B. Soroko was released on the protest of the prosecutor for supervision of places of detention, due to the fact that she and Y. Soroko have a minor child. All the arrestees were released at different times and in different places, to prevent them from meeting. Friends and relatives of the arrested, who gathered near the prison, were dispersed by the militia. Y. Soroko and Z. Melamed were taken directly from prison to the UKGB for Kyiv Oblast, where they were ‘conversed with’ in a threatening tone by KGB officer Davidenko. He stated that ‘circumstances have changed,’ that the KGB now has its ‘hands untied,’ and next time they face a much longer sentence (Yuri Soroko and Mark Yampolsky were arrested for 15 days in February-March 1972 for visiting the Kyiv synagogue)” [47].

And further, in the same place—“The Chronicle of Current Events,” issue 27, October 15, 1972:

On this day (meaning September 29, 1972), “as usual, wreaths and flowers were laid at the gravestone in Babyn Yar. Later than usual (at 6 p.m.) the official rally began. The speaker focused attention on the Israeli aggression against the Arabs. It was further stated about the multinational Soviet state and that during the tragedy that unfolded in Babyn Yar, many Soviet people of various nationalities perished. Residents of Kyiv came to Babyn Yar to honor the memory of their fallen brothers with wreaths and flowers (several hundred people). The sidewalks were cordoned off by numerous militia detachments. It was permitted to lay wreaths only with red and black ribbons and inscriptions not in the Jewish language (‘its not clear what is written’); white and blue ribbons were ordered to be removed (the color of the Israeli flag). At 7 p.m., militia detachments began to clear the street, by 8 p.m. everything was empty, the light at the gravestone was extinguished” [47].