In an interview, Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska recalls the following episode.

“I remember an episode now. They were living on Povitroflotskyi Prospekt at the time… And so, before some trial, I think it was Svitlychny’s trial, they came to see Marta and we went for a walk toward Zhuliany. Planes were constantly taking off there, and it was so noisy that you could say whatever you wanted and no one would hear. And so I’m walking in the middle, with Lyolya Svitlychna on my right and Marta Dziuba on my left. And we’re discussing Svitlychny’s trial. Lyolya says: ‘Let him get the full sentence, just as long as he doesn’t break! It will kill him, he won’t be able to live with it!’ Marta replies: ‘Lyolya, what are you saying! He needs to be freed!’ I remember Lyolya was constantly being blackmailed—Ivan seemed terribly soft, but they were mistaken, because he was so stubborn, so firm, that you could pile anything on him, but if he knew something had to be a certain way, then that’s how it would be. And they realized this and gave him the full sentence out of spite. But there were always rumors being spread that he had broken, that he would write a recantation. And I remember Lyolya coming to me after the trial—all put together, in some black suit, with a beautiful brooch, her eyes shining: ‘The full sentence!’ You could only tell this to someone who understands, but it’s the truth, that’s how it was, I’m not making it up. There was such joy—they gave her husband 12 years, but she was radiant.”

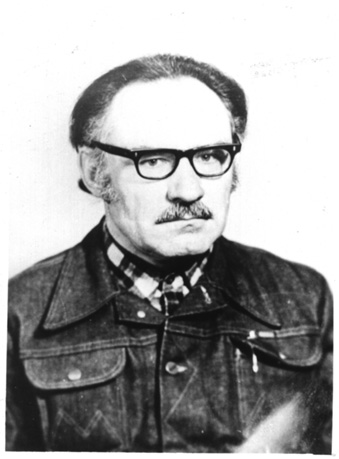

This difference in the attitudes of Ivan Svitlychny’s and Ivan Dziuba’s wives toward their husbands’ arrests and subsequent fates explains a great deal. Leonida Pavlivna Svitlychna understood that her husband would not be able to live with a recantation, that he would not forgive himself for this weakness, and so she was glad that he had held firm and received the maximum sentence—7 years in labor camps and 5 years in exile. And this sentence did indeed kill Ivan Svitlychny: after a stroke in August 1981 while in exile in the Altai, he was unable to work and died in 1992. Marta Volodymyrivna Dziuba was certain that her husband, with his severe tuberculosis, would not survive life in prison, that it would kill him, and she did everything she could to get her husband released and thereby save his life.

In my opinion, both were right.

The KGB hastened to send the issue of *Literaturna Ukrayina* containing Ivan Dziuba’s recantation to the political camps so that his friends could read it. The reaction of the Ukrainian political prisoners was overwhelmingly negative; only a few of them, including Ivan Svitlychny, refrained from accusations of betrayal. I believe this is precisely why the KGB came up with the idea of correspondence between the friends. But Svitlychny’s very first letter to Dziuba never reached its addressee and was confiscated—for obvious reasons: the KGB did not want Svitlychny’s uncomfortable questions to influence Dziuba.

Below we publish a document from the Sectoral State Archive of the SBU[1] containing Ivan Svitlychny’s letter—a brilliant document of its era. As far as we know, this document has not been published before.

[1] SSA of the SBU, f. 16, op. 3, spr. 2, t. 9, pp. 348-362.

CASE 2 VOLUME 9

TOP SECRET

Series “K”

TO THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF UKRAINE

Comrade V.V. VERBITSKY

MEMORANDUM

In addition to No. 39 of January 17, 1974, we report that the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR is continuing its operational surveillance of the behavior of DZIUBA, I.M., as well as measures for his ideological re-education and separation from the nationalist environment.

To this end, several meetings and prophylactic conversations have been held with DZIUBA by an officer of the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR, during which he expressed satisfaction with his situation and his job at the newspaper of the Kyiv Aviation Plant. DZIUBA also reported that during the elapsed period, he had met with some former like-minded individuals, although he himself had not sought such contacts and they were of a random nature. In particular, he described a chance meeting in the city with SVITLYCHNA, L., who, citing a request from her husband (the convicted subject of the “Blok” case, SVITLYCHNY, I.A.), confirmed his home address for mail correspondence.

According to operational data, this meeting was indeed accidental, which was also confirmed in a conversation with an operations officer by DZIUBA’s wife. By operational-technical means, it was recorded that she expressed sharp dissatisfaction with this, opining that DZIUBA should have refused to speak with SVITLYCHNA, and advised him to “be on guard and not engage in such conversations.”

In a conversation with an officer of the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR, DZIUBA also expressed his negative attitude toward such meetings, but stated that he would not be able to avoid random contacts with former like-minded individuals in the future. In doing so, he expressed an unwillingness to inform the operations officer about them, as he believes that certain individuals could be caused trouble. At the same time, he declared his intention to firmly fulfill the obligations he had undertaken and assured that his decision to break with the past was final. According to DZIUBA, his views and perceptions had changed over the past two years; he had begun to see many things differently, more realistically, and had rethought a great deal. He had thought a similar process would occur in his former like-minded individuals, but after meeting with them, he became convinced that the positions of most such persons remained unchanged, and as a result, the conversations that took place only led to misunderstandings.

As a result of operational surveillance of DZIUBA’s behavior, data has been obtained indicating that within his family circle and during meetings with confidential contacts, he demonstrates restraint, avoids conversations on political topics, and does not express his attitude toward his past nationalist activities.

The attitude of his former like-minded individuals toward DZIUBA remains the same; most of them continue to condemn his statement of recantation, viewing DZIUBA’s “capitulation” as a serious blow to the “national movement.”

At the same time, it has been established that some of the subjects of the “Blok” case who remain at liberty or have been convicted have not given up hope of DZIUBA’s possible return to his former nationalist activities and continue to take measures to exert moral influence on him. Along with KOTSIUBYNSKA and NEKRASOV, who sought to influence DZIUBA in this manner, the convicted SVITLYCHNY, I.A., has begun to make similar attempts. In February of this year, he showed an interest in establishing direct correspondence with DZIUBA in order to “try to start a conversation with him.” Later, the censorship of the Skalninsky Corrective Labor Colony confiscated an inflammatory letter from SVITLYCHNY addressed to DZIUBA, in which he sought to exert moral pressure on the latter to keep him in his former nationalist positions and push him to speak out in defense of the convicted STUS, KALYNETS, and other former like-minded individuals (a copy of SVITLYCHNY’s letter to DZIUBA is attached).

It is characteristic to note that SVITLYCHNY, KOTSIUBYNSKA, and a number of DZIUBA’s other former like-minded individuals, while condemning his officially adopted position, are primarily seeking to prevent the preparation of a book refuting the treatise *Internationalism or Russification?*. In this connection, statements have been noted from nationalist-minded individuals that DZIUBA will not write such a book, because, in their opinion, he has remained in his former nationalist positions. The spread of such judgments is also facilitated by the fact that since DZIUBA’s release from punishment, no materials of his directed against Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism, other than the statement of November 9, 1973, have been published in the press.

The KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR, in supporting DZIUBA’s petition for a pardon, proceeded from the interests of his subsequent active use in measures against Ukrainian nationalists. Our considerations on these matters were reported to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine in No. 622 of November 28, 1973.

As a result of the work carried out in this direction with DZIUBA, he has completed the manuscript of the book *No Third Way*, the preparation of which was mentioned earlier in his statement published in the newspaper *Literaturna Ukrayina*. However, in the five months since DZIUBA’s pardon, only two of his essays on the construction of the “3600” rolling mill have been published, and there have been essentially no other materials in the press that convincingly testify to his revision and condemnation of his former nationalist views and his turn toward a break with nationalism.

For these reasons, the plan to use DZIUBA, as one of the former ideologists of the so-called “national movement” in Ukraine, in active measures against Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists has not yet found its practical implementation.

The absence of such publications by DZIUBA is regarded by nationalist elements as a manifestation of his “firmness” and “uncompromisingness,” and gives grounds for spreading rumors that DZIUBA has remained in his former positions. It is this that allows DZIUBA’s former like-minded individuals to count on his return to their camp. Since DZIUBA himself has not yet completely renounced his nationalist convictions and is showing indecisiveness, the current situation suits him to a certain extent, as it does not require him to initiate a public break with his former like-minded individuals.

At the same time, DZIUBA has recently, in conversations with the operations officer, shown more interest in the fate of the manuscript of the book *No Third Way*, and has suggested that the book will probably not be published, which he sincerely regrets, as with this book, according to his statement, he would have confirmed his current position and freed himself from the “attention” of his former “friends.”

Unsure whether the book *No Third Way* will see the light of day, DZIUBA has prepared two articles for publication in the periodical press based on several chapters of this book, in particular, “The International Significance of the Solution to the National Question in the USSR” and “The National Culture of the Ukrainian Socialist Nation and the International Culture of the Soviet People.”

Taking the foregoing into account, we request that, pending a decision on the publication of the book *No Third Way*, the possibility of publishing the aforementioned articles in the newspaper *Visti z Ukrayiny* be considered.

The publication of these articles, even after their revision, is naturally of no scientific value; however, the very fact of DZIUBA’s appearance in print on issues of national relations from a Marxist-Leninist position will limit the ability of foreign OUN centers to use DZIUBA’s name and his treatise in anti-Soviet propaganda. At the same time, this will, in our opinion, have a politically beneficial effect on DZIUBA’s former like-minded individuals and other nationalist-minded persons, and will serve as a convincing confirmation of his condemnation of his former nationalist views.

In addition, the publication of these articles will have a beneficial effect on DZIUBA himself, who has recently begun to look skeptically on the possibility that his materials might be used in the struggle to expose the hostile ideology of nationalism and has started to pay more attention to preparing materials for the factory newspaper on current topics.

Along with further operational measures to shield and separate DZIUBA from his former like-minded individuals, we would consider it advisable to organize regular meetings and educational conversations with him by one or two representatives of the Union of Writers of Ukraine, with a view to gradually involving DZIUBA in active creative work.

For these reasons, we consider it desirable not to impede the conclusion of an agreement by DZIUBA with the “Dnipro” publishing house for the publication of his translation of the novel *Toward Life* by the Ossetian writer Ezetkhan Uruymagova, about revolutionary events in the North Caucasus in 1905–1912, which has been previously published several times in Russian.

In the opinion of the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR, DZIUBA’s intentions for a repeat trip to the “Azovstal” plant should also be supported, and assistance should be provided for the preparation of his planned book of essays on the life and labor of the Zhdanov metallurgists.

We report this for your decision.

ATTACHMENT: as per the text on “8” sheets.

CHAIRMAN OF THE COMMITTEE FOR STATE SECURITY UNDER THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS OF THE UKRAINIAN SSR

V. FEDORCHUK

LETTER FROM IVAN SVITLYCHNY

Ivan!

When they told me I could write you a letter, I was overjoyed. It seems not much time has passed since we last saw each other, but so many events have swept over our heads, so much has changed in our lives and in ourselves, that the very possibility, the very chance to exchange thoughts, to reflect together, as we used to, on our newly acquired—in some ways bitter, in others useful—experience, gladdens me. I write: me, but I hope: you as well. Our current guardians even say that it’s harder for you now than for me—and I have no reason not to believe them, from which it is easy to imagine that your need for contact with living people is no less than mine.

For me, the need for communication is exacerbated by artificial circumstances. The camp censorship, which in theory should perform narrowly specialized, strictly legally defined functions, decides the affairs of my relationships with other people according to its own taste and discretion. My letters and letters to me are confiscated, without them bothering to provide any serious justification for the confiscation. Sometimes they say: “The letter contains information you should not know,”—and in this way, they decide for me and without me what I can know and what I cannot. But more often they find some mysterious “conventions” in the letters: what that thing is—perhaps not even the Almighty knows, and to a request to explain what the censorship sees as these conventions (because one must know this, at least to avoid the risk of another confiscation), they answer even more laconically: “You know yourself.” And there is no way to verify the actions of the censorship, nor to appeal them to anyone.

What one can write about in letters—no one knows, but what one cannot—we are often told. One cannot write about one’s friends and acquaintances with whom one lives in the camp—and if I wanted to tell you something, say, about I. Kalynets, Z. Antonyuk, or V. Zakharchenko, whom you know and whose fate you might be interested in—this alone could be a sufficient “reason” for the confiscation of my letter. One cannot write about camp conditions and camp life in general, and since I see and can see no other life than camp life, what can I write about? “Write about yourself,” the mentors of various levels and ranks repeat. But what does it mean to write about oneself without mentioning the environment, living conditions, people, etc.? I am not even talking about the fact that one’s own person is not such a rewarding topic for everyone that it is worth focusing all one’s interests on it, but even about health it is better to write when it is not deteriorating, especially from camp conditions: food, medicine, etc. (the censorship elevates such a delicate topic to the level of almost state secrets). And one can understand people who sometimes completely refuse such, if I may say so, a right to correspondence and delegate these functions to the camp administration, so that it—within the legal limit—routinely informs relatives about the health of so-and-so.

This sounds wild, but it all easily fits into the general atmosphere of camp life. Everything here is imbued with incomprehensible paradoxes, with a Kafkaesque logic of “the opposite.” It would seem that, according to the norms of our society, a spirit of collectivism should be instilled or at least stimulated among the prisoners. However, it is precisely manifestations of collectivism that are feared here like the devil fears holy water. If prisoners are friends, it is considered something suspicious and dangerous, and it is counteracted under various pretexts. Officially, no one can write a statement or a complaint for his comrade. No one has the right to give a small gift, say, to his friend on his birthday. Everything here is aimed at the de-socialization of the individual, at the cultivation of separate units, of philistines who, besides their own person, should know no other living interests. How poor Makarenko must be turning in his grave from such “pedagogy”!

Now do you understand why I was overjoyed when they told me I could write you a letter? But when I took pen in hand, it turned out to be not so easy to write. Now, in these new conditions, questions arise that would have been strange before: what to write about? and—to whom to write?

Yes, yes: what about, and to whom…

The former I. Dziuba I knew, I think, quite well. I consider all sorts of exaggerations in assessing my friends to be in bad taste and will not resort to beautiful and grand words, but even without exaggeration I can say: the former I. Dziuba is associated in my mind with the image of a man and a citizen who in his actions was guided by a moral code of the highest caliber and never sacrificed any public interests for his own.

Now you have declared: “that ‘Ivan Dziuba,’ who allowed himself to be made a byword and who wasted years of his life on political wild-goose chases, is no more and will be no more. There is a man who is pained by the awareness of his unfortunate mistakes and wasted time and who wants one thing and thinks of one thing: to work and work, to at least somewhat make up for what was lost and to overcome what was wrong.”

So, the I. Dziuba I knew is gone, and there is a new I. Dziuba, and logically, before writing to him, I should learn more about my addressee.

Your “statement” partially answers this. But, unfortunately, only partially, only summarily; much—at least for me—remains unclear and unclarified, and without this I can neither imagine my new addressee, nor, much less, speak with him in the old tone. I am interested to know what exactly the new I. Dziuba has severed from the old, and what he has inherited, and how far the revaluation of values has gone: does it concern only his worldview, or has it also seized his moral principles?

You know that I am tolerant of others’ views and convictions. Yevhen even said at his trial: “cosmic tolerance”—and in his words I felt a note of reproach. I admit to such a sin, but—I am not ashamed of it. Yes, I am tolerant of others’ views, and of their evolutions, changes, revisions—even the most cardinal ones. The only faith I profess as sacred has a charming name for me: “democracy,” and its cornerstone is tolerance. And your statement, although in many ways unexpected for me, did not strike me as it did many who considered it incredible, implausible, diplomatic, and even a forgery. I do not have such a low opinion of you as to assume that “statement” was written for you, and you only lent your name to it. Nor do I want to think that the “statement” was caused by the horrors of imprisonment and the prevalence of the personal over the civic. And I cannot believe that it was a diplomatic act, calculated to achieve something desired in another, larger matter by conceding in one, smaller one. All such assumptions, offensive and humiliating, are too contrary to the image of the former I. Dziuba for me to take them seriously.

In a word, I proceed from the fact that you wrote the “statement” yourself and, as they say, in your right mind and with a sound judgment. Despite all this, I repeat, I am tolerant of your revision of your own convictions, that is, I recognize your full right to such a revision and do not think that we have nothing left to talk about. The only thing I want to clarify, before our epistolary relations begin (if they are indeed possible), is the question of the nature and limits of your revision. I am tolerant of any and all convictions, even those absolutely unacceptable to me. Few understand or justify my tolerance, and even the person closest to me—my wife—often reproached me when I entered into contact and engaged in arguments with people whose worldview was alien, or even hostile, to me. I, however, often derived great pleasure and benefit from such contacts and disputes, sometimes more than from communicating with my like-minded friends and allies.

And I have always considered and still consider the recognition of others’ right to think differently from me to be the first commandment not only of all disputes, but of life relations in general. I am tolerant of all kinds of views, except those that deny my right to my own convictions, that is, are based on the principle of intolerance toward others. For if one thinks carefully, this is not about convictions, not about worldview, but about morality, about the attitude toward the human person, about the recognition or denial of their right to be a person, and “ordinary fascism,” as is known, begins precisely with such intolerance and is based on it. I am tolerant, but remember: when V. Moroz came out against you with his “Among the Snows,” I was on your side, largely because in Moroz’s article there were palpable notes of intolerance toward dissenters. And so, before entering into epistolary relations with you, I want to clarify just this: have you changed only your views, or also your morals? Do you grant others the right to think differently from you, or does that alone make a person your personal enemy, unworthy of your high attention?

I have not only purely logical grounds for asking you this question. It would be ridiculous to ask the former I. Dziuba this: the most notable quality of the former I. Dziuba was his tolerance for people—a tolerance no less, and perhaps even greater, than that of your humble servant. Now, however, after your “statement,” after the “revaluation and rethinking of your positions and views,” I do not know what remains of your former tolerance either.

“From all that has happened,” you write, “I have drawn a conclusion: one must not forget that we live in a world of fierce class, ideological, and political struggle, where there is no ‘neutral territory,’ where one cannot be ‘a little’ for Soviet power, for the policy of the Communist Party, and ‘a little’ against. Inexorable reality will sooner or later force one to make a final choice.”

If these words are taken in general, abstractly, only in the context of your “statement,” but outside the context of our social life, one can hardly say anything of substance against them; in any case, they do not evoke any polemical emotions in me. It is only strange that you have drawn such a banal conclusion only now, and as a result of what you call a “great civic and personal tragedy.” What a need to endure tragedies for such axioms! This is alarming and leads to another, ultimately also simple and banal thought: the thought that the most abstract banalities and the most banal axioms do not exist in themselves, without life connections and contexts, and when your words are placed in such connections and contexts, they sound somewhat different.

What does it mean to be “a little” for and “a little” against?

Here it would be appropriate to recall the tragedy of people who saw all those outrages that were later called the cult of personality and did not remain silent: were they also, not understanding banal truths, “a little” for and “a little” against, and in the heat of battle sought “neutral territory,” or was the “little bit” attached to them an act of political speculation? Here it would be appropriate to recall how Khrushchev turned the abstractly innocent formula of “for” and “against” into a political cudgel with which he very indelicately taught artists to create artistic values. Here it would be appropriate to recall that both Molotov’s group, and later Khrushchev himself, left the political arena not so much because of personal factors as because of different understandings of what communism and Soviet power are and how they could best be served. Here it would be… But let’s not touch high politics, especially contemporary: it is persona non grata for us, and its ambitions cost us mere mortals too dearly. We, men of letters, have more than enough examples in our own field of how the sacramental “a little” grew out of an absolute “nothing,” and when needed, easily turned into a menacing “anti.” Were M. Rylsky or Yu. Yanovsky really “a little” against when they were accused of all the mortal sins of bourgeois nationalism? And what, besides the desire, was needed to see seditious “little bits” in V. Sosyura when he came out with his “Love Ukraine?”

And have such “little bits” diminished in our time? If the matter of choosing a life position has been simplified for you to the point that no “little bits” remain, I will allow myself to ask: who did more for the development of Soviet society—A. Solzhenitsyn, who with his works awakened in us a civic conscience and a sense of responsibility for all that we do and what is done around us, or V. Kochetov, to whom everything that happened after the 20th Congress of the CPSU seemed to be moral and political degradation, and the way out and salvation was seen in the restoration of Stalinism? How do you imagine those “little bits” that characterize the socio-literary confrontation of the Tvardovskys and Nekrasovs with the Gribachovs and Korniychuks?

Or do you remember what a celebration it was when—after a long poetic lethargy—the “Sixtiers” entered literature—Lina Kostenko, M. Vinhranovsky, I. Drach—and what hopes were placed on them? And what came of it? Lina has been living with a gag in her mouth for more than ten years, and I. Drach stays in literature with poems that admirers of his talent are ashamed to read—ashamed for I. Drach, ashamed for poetry, ashamed for their own hopes and expectations. But the “Sixtiers” were at least lucky enough to enter literature, their names are at least known to readers, but M. Vorobiov, V. Kordun, V. Holoborodko, V. Stus—poets whose talents are not inferior to the “Sixtiers,” and sometimes even surpass them—did not even experience such happiness. And V. Shevchuk? And V. Drozd? How many unpublished—and better—works remained in their desks and in editorial portfolios? And XXXXXX that they irritated high politics: in the poetry, say, of the same M. Vorobiov or V. Holoborodko, pure politics never even spent the night. And I don’t have to tell you how our literature was bled dry by this “artistic genocide.”

Now tell me, can you call the defense of these artists that “little bit” against which you now consider impossible for yourself? And do you agree that our mutual friend V. Stus, who, with anxiety and pain for our literature, for its truly catastrophic state, appealed to the official public, thereby became a particularly dangerous state criminal and his severe punishment is fully deserved? Do you see any crime at all in the poetry of I. Kalynets, who was convicted precisely for his artistic work?

These are the questions to which I would like to have an answer before entering into epistolary relations with you. I would like to maintain such relations (while others are impossible) and I hope that they can be useful for both of us, but if your “statement” is not only a belated discovery of elementary truths, but is also intended to be the gag with which literary speculators and hacks will silence the Kostenkos and Shevchuks, the Vorobiovs and Holoborodkos, finding various “little bits,” and if necessary “a lot,” wherever their instinct for self-preservation and career leads them—then we are talking not only about the “revaluation and rethinking of your positions and views,” but also about a revision of your moral principles, about a declaration of militant philistinism, combined with no less militant intolerance for all who think differently from you, and then—alas, to my great regret!—we will have nothing to talk about.

In a word, no revaluation and rethinking of my convictions worries me as long as they are based on the firm foundations of an unblemished, pure morality. During the investigation, as it seems to me from your case (and I do not know it in its entirety), you apparently did not cross these boundaries and did not disgrace yourself, like P. Yakir or Z. Franko, with the desire to save your own skin at the expense of others—this gives me grounds to hope for the maintenance of our former relations. If, however, in a revisionist fervor, you have gone so far as to make your moral principles a bargaining chip (and I would not want to believe this), then I will mourn for the repose of the soul of a former friend, and I will [perceive] the new I. Dziuba as a person who, instead of choosing an appropriate pseudonym, is shamelessly speculating with someone else’s name.

Beyond all that, I would like to know how you are feeling, what you are doing, how your anti-*Internationalism or Russification?* is going, whom you have seen, whether you are satisfied with yourself, and in general—what is new with you and around you, in our best of all possible worlds?

I await your reply.

I. SVITLYCHNY