Jewish topics in the territory of “historic Russia” (lands that were once part of the Russian Empire/USSR) have always attracted the attention of researchers at various levels—from academic historians to journalists and human rights activists. Their research places a special emphasis on the Soviet era, particularly the Stalinist period or the “Era of Stagnation.” However, the object of study is usually the entire USSR as a whole, rather than a specific Soviet republic. Therefore, it is timely to consider the history of discrimination against Jews and their struggle for their rights in the Ukrainian SSR during the rule of L. I. Brezhnev, Y. V. Andropov, and K. U. Chernenko. It was during the “Stagnation” era that this issue became particularly acute in the Soviet Union (and in the Ukrainian SSR in particular), which will be examined in this article.

The problem of Babyn Yar had already made itself felt during Khrushchev’s time. On March 13, 1961, the Kurenivka tragedy occurred in Kyiv—a man-made disaster in which a powerful mudflow from Babyn Yar broke through a dam, flooding the Kurenivka district and causing numerous casualties. Even then, rumors of “God’s punishment,” of revenge by the Jews executed in the ravine, spread among the city’s residents—a notion the Soviet authorities denied, using the site of mass human death as a dumping ground for industrial waste.

Another landmark event in the country’s public life was the publication of Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem “Babi Yar” in *Literaturnaya Gazeta* on September 19, 1961. It was dedicated to the twentieth anniversary of the mass shooting of Jews. The author repeatedly recited this poem at various events. In it, Yevtushenko was the first to state directly that the Jewish population of Kyiv had been annihilated at Babyn Yar. This contradicted the official government version, which claimed that Soviet citizens of various nationalities were killed there. A year later, composer Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his Thirteenth Symphony based on Yevtushenko’s poem, which served as the libretto for its first movement [1].

“Babi Yar” resounded as a powerful and sincere voice of protest; its lines tore through the dense web of antisemitism that had enveloped Soviet public consciousness. The poem became iconic and was the subject of much controversy. Jews began the fight to install a memorial at Babyn Yar.

Yevtushenko’s poem found a wide response among Jews worldwide, especially in Israel. On March 8, 1963, Khrushchev spoke of the “revival of the Zionist rat” in the USSR due to the international uproar caused by “Babi Yar” and the sympathy Israelis showed for the poem [2].

Therefore, in September 1965, a closed competition for monuments was announced (and held) simultaneously for two locations: Babyn Yar and the site of the POW camp in Darnytsia [3].

The review of the projects was scheduled for September 1965, with the expectation that the monument would be built the following year. It was this competition, about which almost nothing has been published to this day, that became the stumbling block in the Babyn Yar issue.

Although the competition was closed, many architects submitted their designs. Some proposed two or even three projects. The public found the memorials proposed by the well-known Kyiv architects Iosif Karakis and Avraam Miletsky to be particularly interesting.

I. Karakis’s project depicted the seven symbolic ravines of Babyn Yar. Bridges were thrown across them (the preserved part of Babyn Yar would be turned into a sanctuary where no human foot should tread), and the bottom of the ravine would be covered with red flowers (poppies) and stones—a reminder of the sea of blood shed there by Soviet citizens. He offered three options for the central part of the monument-memorial. The first was a statue of mourning for the dead, into which images of heroism, suffering, and death were carved like unhealing wounds. The second was a concrete monument—a wall pierced by the silhouette of a person; along the right side of a ramp, on a concrete retaining wall, were mosaic panels of natural granite on the theme of Babyn Yar. The third was a group of petrified human bodies in the form of a split tree with a two-tiered memorial inside, where the main role was given to the frescoes of Zinovii Tolkachov. To the left of the entrance, beyond the ravine, was a memorial museum, partially dug into the ground.

The project proposed by A. Miletsky (whose mother and grandmother died in Babyn Yar) envisioned an entire complex that would begin with a granite block inscribed with “Babyn Yar” in several languages and end with a retaining wall featuring seven artistically designed ravines. In one of them lay the neck of a violin, in another a ball, in a third a broken baby carriage, an umbrella, and so on.

Equally striking was the monument project created by sculptor Ada Rybachuk and architect Volodymyr Melnychenko, titled “When the World is Destroyed.”

The discussion of the works was heated. Some insisted that since prisoners of war had died at Babyn Yar, they should be depicted. Others believed that the seven ravines in the projects by Miletsky and Karakis represented the Jewish menorah, which had become the emblem of Israel. The majority of officials leaned toward the view that the Jewish theme, and with it the death of the civilian population, should be removed from the memorial.

The comment book, in which antisemitic statements appeared alongside entries supporting the projects, was confiscated, and the competition was annulled. A second competition was announced under the title “The Road, Death, and the Rebirth of Life.” The Union of Architects recognized a monument depicting a figure with a flag as the best project. This project was submitted for approval to the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Petro Shelest.

Perhaps not catching the sycophancy of the Union of Architects, he only said: “I don’t think this is for Babyn Yar.” No monument was erected at the site of the death of tens of thousands of Kyivans by the 25th anniversary of the tragedy.

Meanwhile, in September 1966, activists of the movement for Jewish national revival made the first attempt at open resistance to the Soviet authorities’ intention to destroy the memory of Babyn Yar.

In fact, there were two such attempts—on September 24 (the anniversary of the start of the shootings at Babyn Yar according to the Jewish calendar, on the eve of Yom Kippur) and on September 29, 1966 (the anniversary according to the Gregorian calendar).

Film director Rafa Nakhmanovich wrote in his memoirs: “A friend of my wife’s came and told us that young Jewish men were planning to mark the anniversary of the shooting at Babyn Yar.”

In popular memory, the central events of the rally on September 29, 1966, were the speeches by V. P. Nekrasov, I. M. Dziuba, and Dina Pronicheva. Squeezed into the crowd, without any technical equipment (microphones or amplifiers), they were barely audible to those immediately around them, but the echo of what they said that day can still be heard today. Dziuba’s speech at that unofficial rally spread throughout Kyiv [4].

The rallies of September 1966 were a complete surprise to the Soviet authorities, but they obviously made a huge impression: on October 1, 1966, the First Secretary of the Kyiv City Party Committee, O. Botvin, wrote a detailed report on the rally to the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Shelest, and on October 12, a special meeting of the Kyiv City Party Committee was convened to discuss the event. Between these dates, Shelest sent a report on the rally to Moscow, to the Central Committee of the CPSU.

Just three weeks after the rally, a stone appeared between Dorohozhytska and Melnykova streets with the inscription: “A monument to the Soviet people—victims of the fascists’ crimes during the temporary occupation of Kyiv in 1941–1943—will be erected here.” There was no mention of the mass shootings of Jews. Two crossed lines, created by the stone’s natural structure, seemed to symbolically cross out this inscription, refuting its content. The installation of the stone, however, also had a positive significance—from then on, the location for memorial ceremonies at Babyn Yar was unequivocally defined: at the stone. The rallies and gatherings of all subsequent years would now take place there.

Another aspect of the memorial ceremonies “at the stone” appeared at the same time as its installation—the authorities no longer wanted to ignore it, and from now on, all memorial ceremonies were to be conducted according to their script and direction.

On July 2, 1976, for the 35th anniversary of the tragedy, a monument was unveiled in the upper part of Babyn Yar near Dorohozhytska Street with the inscription: “To the Soviet citizens and captured soldiers and officers of the Soviet Army, shot by the German fascists in Babyn Yar.” For a long time, it was the only reminder of the Babyn Yar tragedy [5].

In general, from the very beginning of its existence, the movement for Jewish national revival (in all its forms, including, of course, the Babyn Yar phenomenon) was under the constant surveillance of state (police, KGB) and party (the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Central Committee of the CPU) bodies—lower-level authorities did not deal with this. First and foremost, they regarded what was happening at Babyn Yar as “actions by Jewish nationalists aimed at inciting nationalist tendencies among the Jewish population of the city of Kyiv” (from Shelest’s 1966 report to Moscow). But by 1970, Andropov already knew (and reported to the Central Committee) that “under the influence of Zionist and anti-communist propaganda from abroad, a tendency toward unification and anti-Soviet actions is observed among Soviet Jews infected with nationalism, under the guise of the struggle ‘for the awakening of national self-awareness and the development of Jewish culture.’ In 1969–1970, there was a process of gradual unification of illegal Zionist groups and organizations that had emerged in different parts of the country into an underground Zionist party...”

Thus, Babyn Yar slowly but surely became a place of confrontation between the Soviet government and the democratic aspirations of the Jewish national revival.

The first open clash occurred in September 1968. As the main part of the audience present at the official rally began to disperse, Borys Kochubiyevskyi suddenly began to speak—about how outrageous it was to talk at Babyn Yar about Zionists and “Israeli aggressors” without mentioning that Babyn Yar was the place where many thousands of Jews had died. At the end of November, Kochubiyevskyi’s home was searched, and a week later, on December 4, 1968, he was arrested.

In May 1969, a trial was held at which Gerenrot, Bukhina, Koyfman, and Ozeryanskyi testified for the defense. The court rejected the defense witnesses’ evidence, stating that “all five of these people are friends of the defendant and fully supported the defendant’s Zionist views in court.” Kochubiyevskyi was sentenced to 3 years under Article 187-1 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (“Dissemination of deliberately false fabrications that defame the Soviet state and social system”). He served his sentence in Institution YAE 308/26, Zhovti Vody, Ukrainian SSR.

In a letter addressed to Shelest from the First Secretary of the Kyiv City Committee of the CPU, Botvin, dated September 16, 1969, it was stated: “As it has become known to the Kyiv City Committee of the CP of Ukraine, a certain part of the nationalistically-minded citizens of Jewish nationality intends to hold a gathering at Babyn Yar on September 29 of this year... to lay out a six-pointed star with flowers near the memorial stone.

In this regard, a proposal is made to hold a rally of Kyiv’s working people at Babyn Yar on September 29, 1969, at 2 p.m., following last year’s example, dedicated to the memory of Soviet soldiers and citizens who died at the hands of the fascists during the temporary occupation of the city.

It is proposed that the rally be opened by the secretary of the city party committee, with speeches by 2-3 participants of the Great Patriotic War (of Jewish nationality), a writer, and the secretary of the city Komsomol committee.

The Shevchenkivskyi District Committee of the CP of Ukraine has been instructed to carry out preparatory work for counter-propaganda activities during the rally.”

All this was written on September 16, 1969, almost two weeks before the September 29 rally. It was planned in advance, thoroughly, and very well thought out and prepared: “Contact with the relevant administrative bodies regarding the holding of the rally has been established.”

Since then, similar rallies were held in the appointed time and in a pre-approved format for all subsequent years. A detailed report on the successfully conducted 1969 rally (including the arrest of some “nationalistically-minded citizens of Jewish nationality”) was provided by the same O. Botvin to Shelest on November 17, 1969: “The rally was held in an organized manner; there were no violations of public order. On that day, at 10 a.m., three people approached the memorial stone from D. Korotchenko Street, carrying a wreath of fresh flowers in the shape of two triangles, one on top of the other—in the form of a six-pointed star. When they attempted to lay this hexagon at the memorial stone, citizens of Jewish and other nationalities present began to express their indignation at the behavior of these people. But they still managed to lay the wreath. After that, they lit stearin candles and stood with them for several minutes.

These individuals were detained by officers of the city’s internal affairs department. As it turned out, they were: Isaak Izrailovich Koyfman, b. 1940, unemployed, higher education; Anatoliy Iosifovich Gerenrot, b. 1940, senior engineer at the Kyiv Specialized Repair and Adjustment Administration, higher education; Leonid Izrailovich Kazarovytskyi, senior engineer at Diprosilmash, higher education.

The relevant administrative bodies have carried out the necessary work with these citizens.

The party and administrative bodies of the city of Kyiv are taking measures to prevent nationalist and other anti-social manifestations in the future.”

The third person who carried the triangles to the memorial stone was Borys Ozeryanskyi, but for some reason, the “relevant administrative bodies” did not take him away. They took Leonid Kazarovytskyi, who was not seen in Jewish circles either before or after this incident. The detainees (Koyfman and Gerenrot) rightly suspected him of being a plant and behaved accordingly.

In short, as soon as the formal, official part of the ceremony ended, Jewish activists would appear “from behind the hill,” and the informal part of the event, popularly known as “Babyn Yar this year,” would begin. This usually did not end well—the police and other agencies, trained by many years of confrontation at Babyn Yar, brutally and methodically suppressed any attempts at Jewish independent activity [6].

The events of 1969 obviously left an indelible mark on their memory, so the Soviet authorities prepared for each new anniversary thoroughly and in advance (at the level of the Chairman of the KGB of Ukraine and the Central Committee of the CPU, no lower).

A report from the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR to the Central Committee of the CPU dated September 18, 1970, stated that “The republic’s Committee for State Security has received data that Jewish nationalist elements intend to organize an anti-social action in the city of Kyiv in the Babyn Yar area on September 29, 1970.

Last year on this day, they laid a Zionist star made of fresh flowers at the memorial stone on the burial site of the victims of fascism, lit candles, and distributed leaflets.

According to their plan, this year this action should be of a loyal character and not go beyond the bounds of legality.

On this matter, we are investigating H. N. Diamant, a senior researcher at the observatory of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR…”

A KGB memorandum to the Central Committee of the CPSU dated August 10, 1971, reported that “On August 1 in Kyiv, near the memorial stone in Babyn Yar, a group of 12 Zionist-minded Jews attempted to stage a ten-hour ‘hunger’ strike to protest the refusal to issue them permission to leave for Israel.

The state security organs became aware of these intentions of the Zionist elements in advance, and appropriate measures were taken to prevent them. In particular, on July 29, the said persons, invited to the OVIR of the Kyiv City Council’s UVD, were informed that the issue of leaving for Israel could be resolved positively on the condition that their families leave the USSR in full, including their parents.

The conversation held at the OVIR shook the intention of a number of individuals to gather at Babyn Yar. However, instigated by extremists, they appeared at the appointed place, having previously sent a telegram to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR with a statement declaring a strike.

The measures taken thwarted the Zionists’ plan. In coordination with the party bodies, the participants of the provocation were detained for violating public order, subjected to a fine, and arrested for 10-15 days” [7].

In 1971, August 1 fell on the day of “Tisha B’Av”—the day of the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, traditionally considered a day of mourning for Jews. E. Davidovich, I. Raiz, E. Rabinovich, A. Fingerman, I. Greidinger, E. Lantseter, A. Navelt, N. Remenik, S. Toverovska, and L. Toverovskyi took part in the hunger strike. They were joined, but did not fast, by 66-year-old Leichenko-Velednytska, who suffered from glaucoma. All of them were detained and taken to the Darnytsia police station, and then to the people’s court of the Shevchenkivskyi district (Kyiv). There they were sentenced for violating public order to 10-15 days of imprisonment. Leichenko-Velednytska was fined 10 rubles [8].

Note that, unlike the Ukrainian authorities, who continued to call Jewish activists “Jewish nationalists,” the KGB of the USSR called them “Zionist-minded Jews” and spoke of “the intentions of these Zionist elements.” A private event in Kyiv was being discussed at the all-Union level, at the level of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the central administration of the KGB.

Not without pressure from the security services, the resolutions of the Central Committee of the CPSU “On measures to strengthen the fight against the anti-Soviet, anti-communist activities of international Zionism” (dated February 1, 1972) were approved. On September 7, 1972, the secretariat of the Central Committee of the CPSU, with the participation of M. Suslov, F. Kulakov, P. Demichev, V. Kuznetsov, and others, approved the “Plan of basic propaganda and counter-propaganda measures in connection with the latest anti-Soviet campaign of international Zionism,” prepared by the heads of the Central Committee of the CPSU departments, Firyubin and Yakovlev. An important role in its implementation was assigned to the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the USSR, which was instructed to “take measures to identify and suppress the hostile actions of the enemy’s special services, foreign Zionist organizations, and Jewish nationalists within the country.” Thus, in addition to the already traditional propaganda measures, this and other party documents contained a number of new elements—the use of open repressions against the so-called “Jewish nationalists.”

Based on the directives of the highest political leadership of the USSR, the Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPU, V. Malanchuk, and the head of the propaganda and agitation department of the Central Committee, A. Myalovytskyi, on August 15, 1973, proposed to instruct the Prosecutor’s Office of the UkrSSR, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the UkrSSR, and the Committee for State Security under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR to “strengthen the work of exposing and bringing to criminal responsibility active propagandists of the ‘movement’ for the emigration of Jews from the USSR, and emissaries of foreign Zionist centers.” As a result, every more or less significant action by Jewish refusenik activists did not go unnoticed by the law enforcement agencies of the Ukrainian SSR [9].

An illustration of the next events of 1972 near the memorial stone in Babyn Yar can be found in O. Botvin’s report to the Central Committee of the CPU (personally to Comrade Shelest) dated April 12, 1972: “Regarding the gathering of citizens near the memorial stone to the victims of fascism in Babyn Yar, Kyiv.

The Kyiv City Committee of the CP of Ukraine reports that on April 11 of this year, at 7 p.m., an unauthorized gathering of citizens of Jewish nationality took place near the memorial stone in Babyn Yar on the occasion of the 29th anniversary of the execution of the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto.

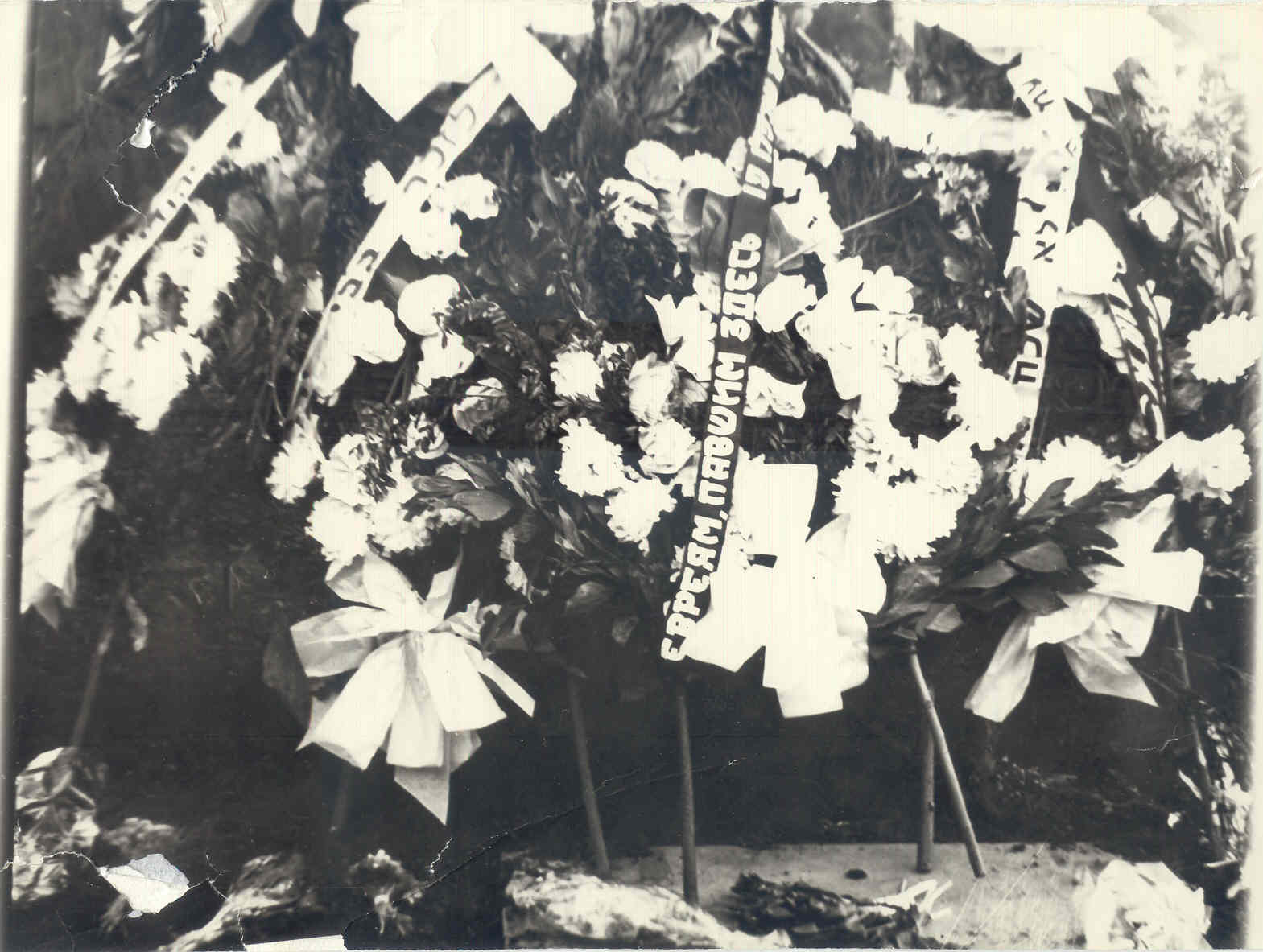

From 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m., about 200 people of Jewish nationality took part in the gathering. In addition, there were more than 200 passers-by. Four wreaths were laid at the stone with inscriptions on ribbons in Russian and Hebrew with the following content: “To the Victims of Warsaw,” “To the Heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto,” “We will not forget, we will not forgive,” “To those who did not submit.”

The ribbons with inscriptions were stylized to resemble the state flag of Israel.

The composition of the participants was diverse—there were elderly and middle-aged people, and youth. From the behavior of those present, it can be concluded that the vast majority came to truly honor the memory of relatives and loved ones who died during the Great Patriotic War, while the organizers of this gathering and the youth present were nationalistically-minded people who had fallen under the influence of Zionist propaganda and tried to use it for their provocative purposes. Some of them pinned Zionist signs to the lapels of their suits and behaved defiantly.

There was even an attempt to organize a speech before those present, but vigilantes from the motorcycle factory, including Jews, took measures to prevent a rally from being held. 7 people who did not react to the vigilantes’ remarks and disturbed the peace of those present were detained by the police and will be held administratively liable.

The gathering was preceded by organized actions of extremist-minded citizens of Jewish nationality who are using various methods to obtain permission for their departure to Israel. As it turned out, long before this, they had sent a letter to Israel stating that they had appealed to the Kyiv City Executive Committee for permission to hold a rally in honor of the victims of fascism who died in the Warsaw Ghetto. The content of the letter was broadcast to the Soviet Union on Israeli radio on April 10. The majority of those who came to the gathering responded to this broadcast.

In reality, no letter on this matter was received by the city executive committee. This was a clear provocation by Zionists who pursued the goal of misleading citizens of Jewish nationality and arousing anti-Soviet sentiments in them.

On April 11, the same radio broadcast a telegram from the mayor of New York, sent to the chairman of the Kyiv City Executive Committee. The telegram was received by the city executive committee in the afternoon of April 11…

The city party committee, together with the relevant bodies, is taking measures to strengthen the education of internationalism among citizens of Jewish nationality and to expose the insidious actions of the Zionists.”

“Educational measures” included arrests and detentions. People were detained not only near the memorial stone; they were also detained preventively, long before any anticipated event, to intimidate and create grounds for charges of malicious (repeated) violation. For example, a certificate issued to activist Yuriy Soroka, who was detained for 15 days (from 08.09.72 to 23.09.72) on the eve of the Babyn Yar anniversary (29.09.72), stated the absurd reason—“for an attempt on the life of a police officer.”

In an informational report from V. V. Fedorchuk (Chairman of the State Security Committee of the UkrSSR) to Comrade V. V. Shcherbytskyi (First Secretary of the CPU from May 25, 1972), it was stated: “On October 10, 1974, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine was informed about the measures taken to prevent the provocative action planned by Jewish extremists in the Babyn Yar area on September 29 of this year, in particular, about the exclusion of... the participation in this provocation of a number of nationalistically-minded persons who are grouped around Kagan.

Incoming operational data indicate that Kyslyk, Tsatskis, and other ‘refuseniks,’ being concerned about the passivity of the Kagan group during the events at Babyn Yar, are trying to influence it and involve it in joint active participation in extremist activities.

Thus, on October 10 of this year, Kyslyk attended a lesson on the study of the ancient Hebrew language in the ulpan managed by Kagan and Bernshtein, where he was interested in the composition of the students and their reliability, the possibility of expanding the network of ulpans and recruiting new people into them.

At the same time, he expressed his readiness to allocate several people from among the refuseniks for the leadership of the ulpan...

...After Kyslyk was brought to administrative responsibility for petty hooliganism, which was reported to the Central Committee of the CP of Ukraine on October 15 of this year, the extremists Zlobinskyi, Tsatskis, and Tartakovskyi, fearing the possible application of similar measures to them by the authorities, refused to travel to Moscow on October 18 to participate in the demonstration planned by the Zionists in defense of the Jewish nationalist Feldman, who was convicted in 1973 [to 3.5 years in a corrective labor camp, arrested immediately after the regular annual rally at Babyn Yar]. They have temporarily ceased personal contacts with their connections, avoid appearing in public places, and periodically maintain contact with each other by telephone.” [10].

The rallies continued.

To finally discourage the opposition public from approaching Babyn Yar, the authorities conceived and, in July 1976, erected their own monument in that place: “To the Soviet citizens and captured soldiers and officers of the Soviet Army, shot by the German fascists in Babyn Yar.” In front of the monument, a metal plaque was installed with an inscription in Ukrainian: “Here in 1941-1945, the German-fascist invaders shot more than one hundred thousand citizens of the city of Kyiv and prisoners of war.” As was customary, there was not a word about the Jews.

Viktor Nekrasov wrote on this occasion: “It took thirty-five years for the bronze muscles of fallen fighters and underground resistance members, calmly and confidently looking into the future under the barrels of machine guns, to appear at the place where their grandfathers and grandmothers were shot, overcoming someone’s fierce resistance” [11].

Long-time Kyiv refusenik Kim Fridman later recalled: “I would come to Babyn Yar with my whole family, I would lecture, I would lead a seminar that took place in my apartment... Volodia Kyslyk was a strong, athletic guy. The first time, he was severely beaten right after receiving his refusal, so to speak, for prevention. It happened at work; he was then a night watchman at a boat station. The second time, it almost came to a beating when he came with his friends to honor the memory of the Jews at Babyn Yar. In June 1976, he was beaten again, and warned to disband his scientific seminar. In 1977, he was accused of sending secret materials on nuclear physics abroad, and this was done through the newspaper ‘Vechirniy Kyiv.’ In March 1980, Kyslyk was threatened with arrest if he did not stop meeting with his refusenik friends or foreign guests, and for the duration of the Moscow Olympics, he was placed... in a psychiatric clinic.

...Volodymyr Kyslyk was arrested while returning from a Purim celebration, accused of attacking a woman and beating a man who tried to help her, under the article ‘malicious hooliganism.’ KGB officers who had been tailing him testified as witnesses at the trial. During the investigation and at the trial, Kyslyk refused to participate in the judicial proceedings, stating that he did not want to take part in a completely fabricated case. On May 26, he was sentenced to three years of corrective labor. He served his term in camps in the Donetsk region of Ukraine. During his sentence, he suffered two heart attacks...” [12].

By persecuting Jewish activists for their demonstrations at Babyn Yar, the Soviet authorities violated several articles of the 1936 USSR Constitution at once. For example, Article 124 guaranteed “citizens freedom of conscience, freedom to perform religious rites.” Article 125 guaranteed “freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and rallies, freedom of street processions and demonstrations.” Article 126 proclaimed that “the popular masses of citizens of the USSR are guaranteed the right to unite in public organizations: trade unions, cooperative associations, youth organizations, sports and defense organizations, cultural, technical and scientific societies.” Article 127 guaranteed citizens of the USSR “inviolability of the person. No one may be arrested except by a court decision or with the sanction of a prosecutor” [13].

The same applies to the 1977 USSR Constitution. Article 50 stated: “Citizens of the USSR are guaranteed the freedoms of: speech, press, assembly, rallies, street processions and demonstrations. The exercise of these political freedoms is ensured by providing the working people and their organizations with public buildings, streets and squares, the wide dissemination of information, and the opportunity to use the press, television and radio.” Article 51 indicated: “Citizens of the USSR have the right to associate in public organizations that contribute to the development of political activity and initiative, and the satisfaction of their diverse interests. Public organizations are guaranteed the conditions for the successful fulfillment of their statutory tasks.” Article 52 prescribed the guarantee of freedom of conscience, “that is, the right to profess any religion or to profess none, to perform religious rites or to conduct atheistic propaganda. Incitement of enmity and hatred in connection with religious beliefs is prohibited.” Article 54 affirmed that “citizens of the Soviet Union are guaranteed inviolability of the person. No one may be arrested except on the basis of a court decision or with the sanction of a prosecutor.” Article 57 ordered that “respect for the individual, protection of the rights and freedoms of citizens is the duty of all state bodies, public organizations and officials” [14].

As we can see, in the 1960s, Jewish activists began to hold unofficial (i.e., not sanctioned by official authorities) rallies at Babyn Yar, marking the anniversaries of the mass murder of Kyiv’s Jews. In 1966, human rights writers spoke at such a rally: the Ukrainians I. Dziuba and B. Antonenko-Davydovych, and the Russian V. Nekrasov. The authorities unsuccessfully tried to prevent the rallies: in 1968 and 1972, many of their participants were arrested. And yet, in the late 1960s and the first half of the 1970s, the Jewish national movement in Ukraine developed on an upward trend [15].

As the Jewish movement grew, the rallies at Babyn Yar became more crowded: in 1968, 50-70 people gathered there, in 1969—300-400 people, in 1970—700-800. The authorities, trying to interfere, began to arrange an official rally on this day, where pre-prepared speakers would deliver speeches. They talked about “Israeli aggression,” but did not mention that the people buried there were Jews, killed only because they were Jews. In 1971, about a thousand people gathered in the ravine, including refuseniks from Moscow, Leningrad, Sverdlovsk, and Tbilisi. They laid wreaths with appropriate inscriptions.

Attempts to hold demonstrations, which had already become traditional, continued every year. In Babyn Yar, where official rallies on the anniversary of the Jewish shooting ceased to be held after 1977, 44 people gathered that year—Muscovites could not get to Kyiv as they were detained. In 1981, on the 40th anniversary of the shooting, Jews from different cities again arrived at Babyn Yar [16].

As the chronicles of “Vesti iz SSSR” (News from the USSR) testify, demonstrations at Babyn Yar and repressions against their participants continued. For example, issue No. 18 for 1981 stated: “On September 27, 1981, a group of Jews who intended to lay a wreath at Babyn Yar, the site of the mass murder of Jews during the fascist occupation of Kyiv, was detained at the Kyiv railway station. Two of the detainees are from Kyiv, two are from Leningrad, and one is from Moscow. 4 people were sentenced to 15 days of administrative arrest on charges of ‘hooliganism,’ the fate of the fifth is unknown” [17].

“Among those subjected to administrative arrest for 15 days for attempting to lay a wreath at Babyn Yar in Kyiv are Kyiv refuseniks Svitlana Yefanova and Volodymyr Tereshchenko” [18]. In addition, “for attempting to lay wreaths at Babyn Yar in Kyiv, in addition to Kyivans S. Yefanova and V. Tereshchenko, Muscovites Oleksiy Lorentsson and Valeriy Kanevskyi were also subjected to administrative arrest (for 15 days each), and Leningraders Mikhail Elman and Pavel Astrakhan (10 days each, arrested on September 26, 1981). Muscovites Oleg Popov and Volodymyr Magarik, who intended to travel to Kyiv to lay wreaths, were removed from the train. Muscovites E. Nartova and E. Ravich, who had already arrived in Kyiv, were sent back to Moscow. However, four people from Odesa managed to get to Kyiv, lay a wreath in the ravine, and recite the Kaddish. They left Babyn Yar without being detained” [19].

Besides Babyn Yar in Kyiv, something similar, albeit on a more modest scale, took place at another site of mass shootings of Jews during the Soviet-German war—in Drobytskyi Yar, located near Kharkiv. As participants of the pickets recalled (in particular, refusenik Itskhak Moshkovych), “On the ninth of May, we, the refuseniks, would visit Drobytskyi Yar, the site of the mass shooting of Jews in 1941. What threat to themselves or the Soviet regime did the KGB see in visiting graves? Isn’t this a case of, having burned themselves on milk, they now blow on water? And when one criminal-looking captain told me: ‘If I see you there, I’ll rip your head off!’—he understood perfectly well that he wouldn’t even rip a button off my pants. ‘If I see you on May 9 in the Drobytskyi Yar area—I’ll rip your head off!’—in this phrase I heard not a threat, but desperation. It was as if he were getting on his knees and begging me not to do it, not to go, or at least to show fear of him” [20].

In turn, the well-known long-time Soviet dissident and refusenik O. Parytskyi recalled: “During the war, about twenty thousand Jews were shot in Drobytskyi Yar on the outskirts of Kharkiv. In March 1978, we sent a letter to the regional executive committee with a proposal to organize a subbotnik there to clean up the territory on the eve of Victory Day. We were invited to a meeting with the chairman, who assured us that everything there was clean, the memorial sign had been repaired, and there was no need for a subbotnik. I replied that then we would lay flowers and wreaths to honor the memory of the victims of Nazism. The chairman’s reaction was clearly inadequate. He turned red, jumped up from his seat and shouted: ‘I forbid you to go there with flowers! You have no business there!’

Over the next week, we were summoned to the KGB and warned not to go to the ravine on May 8. In return, they promised to help us get exit visas. The guys came to me and said, well, you know, sorry, but we’re not going to stick our necks out. I didn’t reproach them. But for myself, I decided that this would be my personal demonstration. Polia [his wife] categorically stated that she would never let me go alone. But we didn’t set off as a pair, but as a trio—we were joined by my former colleague from the Institute of Metrology, Lyonya Gugel.

It was raining on the morning of May eighth. In Drobytskyi Yar, located three kilometers from the final tram stop, we headed straight across a field, struggling to pull our feet out of the sticky mud. As soon as we began to descend the slippery slope of the ravine, a line of people in raincoats emerged from behind the curtain of rain. There were three of us, and about twenty of them.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked.

‘And where are you headed?’

‘We are going to lay flowers at the memorial sign.’

‘Passage there is forbidden!’

‘Thousands of people killed by the Nazis are buried here. We came to honor their memory and we will do it!’—The response was:

‘Stop! Don’t move!’

Lyonya and I jumped over the stream that flowed along the bottom of the ravine and helped Polia cross to the other side. Then we took a few steps up the eastern slope and scattered the flowers on the ground. The people in raincoats stood silently opposite, almost right up against us. I didn’t notice any personal feeling in their identical faces. They were ordered—they obeyed” [21].

Thus, even before the emergence of an organized Jewish movement, a tradition of honoring the deceased with a memorial prayer and the laying of wreaths on the anniversary of their deaths had developed in some cities where mass shootings of Jews had taken place during the war. The most famous of these places is Babyn Yar in Kyiv. For many years, relatives and loved ones of those shot gathered there on September 29. With the beginning of the Jewish movement for emigration to Israel, Kyiv refuseniks and even activists from other cities began to come there on this day. Something similar happened at Drobytskyi Yar near Kharkiv.

As we can see, the de facto ban on honoring the victims of the Holocaust on the territory of the UkrSSR fully coincided with the assimilationist policy of the Soviet authorities in other aspects. Moreover, the sites of mass Jewish deaths during World War II somehow became places of activity for the Jewish-Zionist movement, which demanded from the Kremlin the restoration of Jewish national-cultural life and permission for repatriation to Israel. Therefore, the communist authorities tried to nullify as much as possible all the socio-political efforts of refuseniks, dissidents, and other opposition elements. They more or less succeeded in this throughout the “Era of Stagnation,” until Gorbachev’s perestroika in the second half of the 1980s removed the issue of persecution of dissenters from the agenda.

1. For more details on the scandal related to Yevtushenko’s poem, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. *Khrushchev's Secret Policy: Power, the Intelligentsia, the Jewish Question*. Moscow: Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 2012, pp. 351-370.

2. Ibid., pp. 364-365.

3. Part 3. The 1965 Monument Exhibition / Hadashot.

4. Zissels, I. Jewish Samizdat: 1960s – 1980s / Migdal.

5. Yevstafieva, T. On the History of the Establishment of the Babyn Yar Monument / Yevreiskii Obozrevatel.

6. Part 5. Babyn Yar – The Soviet Way, By Default / Hadashot.

7. *Jewish Emigration in the Light of New Documents*, ed. by B. Morozov. Tel Aviv, 1998, p. 113.

8. Ibid., p. 114.

9. Bazhan, O. “Repressive Measures of the Soviet Authorities Against Citizens of Jewish Nationality in the UkrSSR (1960s – 1980s).” *From the Archives of the VChK-GPU-NKVD-KGB*. 2004, no. 22, pp. 115-116.

10. Part 6. Babyn Yar – An Outpost of Zionism / Hadashot.

11. Part 5. Babyn Yar – The Soviet Way, By Default / Hadashot.

12. Kosharovsky, Y. Chapter 44. The Wave of Repression 1980 – 1983 / We Are Jews Again.

13. Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Approved by the Extraordinary VIII Congress of Soviets of the USSR on December 5, 1936 (with subsequent amendments and additions)

14. Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Adopted at the extraordinary seventh session of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of the ninth convocation on October 7, 1977.

15. Ukraine. Jews in Post-War Soviet Ukraine (1945–91) / Jewish Confederation of Ukraine.

16. Alekseeva, L. A History of Dissent in the USSR. The Jewish Movement for Emigration to Israel / Jewish World of Ukraine.

17. September 30, 1981 (N 18) / News from the USSR. Human Rights Violations in the Soviet Union.

18. October 15, 1981 (N 19) / News from the USSR. Human Rights Violations in the Soviet Union.

19. October 31, 1981 (N 20) / News from the USSR. Human Rights Violations in the Soviet Union.

20. Moshkovich, I. Dissidents and Refuseniks / From the History of the Jewish Movement.

21. Parytskyi, A. Confrontation / “Zametki po evreiskoi istorii” online portal.