Under the rule of foreign powers, Ukrainians and Jews lived for centuries in peace and cooperation. Only due to pressure from above was the mutual coexistence of the two ethnic groups destroyed, giving rise to antisemitism. The consequences of this unfree past are still felt today—particularly in the vandalistic acts of radical nationalist and racist circles, or in everyday Judeophobia. The danger of a resurgence of antisemitic ideas in a conservative-nationalist direction against the backdrop of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War makes it vital not to forget the recent manifestations of state antisemitism on Ukrainian lands.

The problem of discrimination against Jews in the Soviet Union is a well-known topic. However, most of the existing work concerns Stalin’s antisemitic campaign of the second half of the 1940s to the early 1950s, or the “Era of Stagnation” of the 1960s–80s (the persecution of dissidents and the struggle of Jews for the right to emigrate). The Khrushchev period has received incomparably less attention from researchers. Despite the relatively liberal atmosphere of the “Thaw” (compared to the previous era), in the words of historian G. V. Kostyrchenko, “if in the last years of Stalin’s rule this policy [of antisemitism – K. K.] was something akin to a blazing flame, then under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, when it was largely ‘damped down,’ it, like an invisible peat fire, only smoldered and glowed. Having limited internal resources for self-reproduction during the ‘Stagnation’ period, official antisemitism was more interconnected than ever with the course of foreign policy, especially in the Middle East, and therefore most often disguised itself as anti-Zionism” [1].

Indeed, the restrictions on Soviet citizens based on ethno-confessional grounds in the 1950s–1960s were an order of magnitude less severe, yet it is precisely for this reason that the repressions of this period have not attracted due attention. Moreover, a myth has emerged, both in public consciousness and in the humanities, of an absence of persecution during the rule of the “liberal” Khrushchev. This article aims to refute this rather established point of view.

Our focus will be directed, first and foremost, at the Kremlin’s anti-legal policy toward Jews in the Ukrainian SSR. However, to understand the problem, we cannot do without the all-Union context, to which we will return throughout this work.

“Khrushchev’s antisemitism was of a plebeian-emotional character, based on the anti-intellectualism of this personality, who flaunted his rustic-proletarian democratism and crude collective-farm humor. His distrust of Jews had a vulgar-everyday basis and was built on a predominant perception of them as fetishists of material well-being and carriers of ‘bourgeois decay’” [2]. To this should be added the personal Judeophobia (a hidden complex) of the Soviet leader, which could not but affect his entourage.

It is important to note one circumstance: in Khrushchev’s time, the Jewish question in the USSR was invariably linked to the Soviet state’s relations with Israel. This was especially true in the first years of the “Thaw”; later, the connection was present mainly through high-profile foreign policy events that had a “Jewish component,” such as the Polish and Hungarian crises, as well as the Sinai Campaign (the Anglo-French-Israeli invasion of Egypt) in the fall of 1956. From the late 1950s onward, after Tel Aviv intensified its efforts to gain international community support on the issue of the persecution of Jews in the Soviet Union (especially regarding the right to emigrate), the Jewish theme became a factor of constant irritation for the Kremlin in its bilateral dialogue with the West.

Back during the “Doctors’ Plot,” an antisemitic agitation campaign was widely launched in Ukraine in medical institutions and on public transport; Judeophobic inscriptions appeared in public places, and pogromist leaflets were distributed; Jewish children were beaten in schools. The party bodies of Ukraine and the Ministry of State Security were flooded with false anonymous denunciations about groups like “Free Israel,” an “underground anti-Soviet Zionist organization” at the Kharkiv Automobile and Road Institute, a “Jewish university” in Korsun-Shevchenkivskyi, and so on. By the end of January 1953, all Jews working in the institutions of the medical-sanitary administration of the Ministry of Health of the Ukrainian SSR were dismissed, as were some professors of the Kyiv Medical Institute; in many places, Jews, especially medical professionals, were subjected to persecution. In February-March 1953, Ya. Lvov, B. Mezhybovskyi, V. Mizrukh, Ya. Pidhaietskyi, B. Sandler, Ya. Taran, Sh. Furmanskyi, and M. Shpilberg were arrested on charges of “Jewish nationalism,” but soon, after Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953, they were all released [3].

After the death of the “father of nations,” Jews, like Soviet citizens of all other ethnicities and confessions, were touched by a wave of partial relaxations and liberalization associated with the beginning of the power struggle in Moscow, and later, the Khrushchev “Thaw.” Thus, mass repressions ceased; even during L. Beria’s time at the Kremlin’s helm, the first wave of amnesty and rehabilitation of Stalin’s victims occurred. This affected Jews primarily through the termination of the infamous “Doctors’ Plot,” which had a clearly antisemitic character. Soon, the members of the “Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee” (JAC) case, who were shot in August 1952, were also rehabilitated. The “Thaw,” although it did not lead to the political rehabilitation of previously banned ideological and political movements, did facilitate the release from prisons of many convicted in various “Jewish cases.” This concerned not only those convicted on charges of Jewish nationalism, members of the JAC (who survived), Jewish media figures, former leaders of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, etc., but also former activists of the Zionist movement in the USSR. With Stalin’s death, antisemitic publications in newspapers ceased, and many Jews who had been previously dismissed from their jobs were able to return to their former positions.

In July 1953, diplomatic relations with the State of Israel were restored (having been severed in February of the same year). Soviet Jews thus regained the opportunity to communicate with Israeli diplomats. The authorities, despite the general easing of the political climate in the country, continued to view Jews with suspicion, considering them, after the creation of Israel, as potential traitors and ideologically unreliable citizens. The mass enthusiasm shown by Jews at the creation of this state was never forgotten by the Soviet government.

Jews were, albeit with restrictions, admitted to prestigious universities [4]. However, they were virtually absent from the leadership of important institutions. The last Jew who had a real influence on the country’s policy-making—the legendary L. Kaganovich—was removed from all his posts in 1957 after the exposure of the so-called “anti-party group.”

On the other hand, during the Khrushchev period, Jews found themselves in a kind of cultural vacuum. This was characterized by the destruction of the traditional Yiddish civilization during the Holocaust, as well as the demolition of Jewish cultural institutions in 1952-1953. The physical extermination of leading Jewish writers and actors associated with the JAC was a truly irreparable loss. To this should be added the absence of Jewish educational institutions, both at the primary and higher levels.

The situation was further aggravated by the fact that the bulk of the Jewish population of the Ukrainian SSR after the war was represented by residents from the country’s interior regions. These people had, for the most part, broken with the Jewish community, received a general education, and absorbed Soviet-Russian culture. These were completely different Jews from those before the 1917 revolution [5].

According to the 1959 census, the number of Jews was determined to be 2,267,814 (1.09% of the total population of the Soviet Union), but in reality, as modern researchers believe, there could have been 15% more. They ranked 11th in number among the peoples of the USSR. About 840,000 lived in Ukraine (2% of the population), making the republic second only to the RSFSR (875,000) in this regard [6].

Ukrainian (and all Soviet) Jews were extremely urbanized. Only 30,000 of them (3.6%) lived in rural areas. A significant Jewish population was concentrated in cities such as Odesa (more than 100,000), Kharkiv (about 80,000), Dnipropetrovsk (35,000), Lviv, Chernivtsi, Zhytomyr, and Vinnytsia. The largest number lived in Kyiv—153,466 people, or 14% of the city’s population [7]. Significant communities remained in smaller towns: for example, in the Khmelnytskyi region, there were 11,600 Jews in cities of regional and district subordination (60.7% of the total Jewish population), in the Zhytomyr region—25,300 (60%), and in the Vinnytsia region—25,100 (50%). However, there was an active process of Jewish migration to the largest administrative, industrial, and scientific centers of Ukraine, Russia, and other republics of the Soviet Union.

1,733,183 Jews in the USSR (76.4% according to the 1959 census) named Russian as their native language. About 23,000 named Ukrainian as their native language, about 25,000—Georgian, and about 20,000—Tajik. Only 403,900 (about 18 percent) named Yiddish as their native language [8]. According to other data, 21.5% called Yiddish their native language (in 1897—97%) [9].

For Ukrainian Jewry, the “Thaw” meant, first and foremost, the end of persecution and the antisemitic campaign in general, the restoration of the possibility of contact with fellow Jews abroad, and the revival of hopes for repatriation. From 1954, Israelis (diplomats, journalists, students) and Jews from other countries began to visit Ukraine. The first report in the Ukrainian Soviet press about the activities of the Israeli ambassador to the Soviet Union, Sh. Eliashiv, mentioned his visit to the Kyiv synagogue on May 1, 1954. In the autumn of 1955, the Kyiv Jewish community received a parcel from the Chief Rabbinate of Israel for the first time. In the following years, despite the authorities’ displeasure, prayer books, kosher wine, and matzah were sent to the Ukrainian SSR (the latter was divided into small pieces so that it could reach as many believers as possible).

In the summer of 1956, two delegations of American rabbis visited Kyiv and Odesa. During their stay in Ukraine, Israelis and representatives of Jewish communities from other countries raised “uncomfortable” questions for the Soviet authorities (about the absence of Jewish schools, literature, and theater, the closure of synagogues, when a monument would be erected at Babyn Yar, and what the prospects were for emigration from the Soviet Union). When meeting with Ukrainian Jews (mainly in synagogues), they passed on relatives’ addresses, letters, and various literature. The Western press began to publish fact-rich critical materials about the difficult situation of Jews in the Ukrainian SSR, particularly in Kyiv, Lviv, and Chernivtsi.

The nature of the dialogue between believers and republican and union authorities began to change: they started receiving requests for the return of religious buildings to the communities. In connection with such a request from the Kharkiv community, the state security organs reported that “the Israeli ambassador maintains contact with the active members of the believers and is undoubtedly informed by the latter about the state of affairs with the synagogue in the city of Kharkiv.” For the first time in the post-war period, the commissioner of the Council for Religious Affairs deemed it appropriate to register “societies of the Judaic faith” in Kharkiv and Vinnytsia. The activities of Jewish religious communities in Poltava, Yevpatoria, Uman, Smila, Mukachevo, Zaporizhzhia, Khmelnytskyi (Proskuriv), Stalino (Donetsk), Mariupol (Zhdanov), Dniprodzerzhynsk, Kryvyi Rih, and Stanislav (Ivano-Frankivsk) became more active [10].

The revival of Zionist life in the Ukrainian SSR mainly affected Kyiv, and to a lesser extent, Lviv, Kharkiv, Chernivtsi, and Odesa. In Kyiv, writers in Yiddish such as I. Kipnis and N. Zabira sympathized with Zionist ideas. A. Feldman, Nelli Gutina, Yevgenia Bukhina, I. Diamant, A. Gerenrot, and others took an active part in Zionist activities. The Kyiv group maintained active contacts with other similar cells, primarily with those in Riga [11].

Amateur circles gradually emerged in Chernivtsi and other cities, where they managed to secure the patronage of trade unions and other organizations. These sometimes unpretentious traveling troupes attracted thousands of listeners—old and young, many of whom did not know Yiddish. An art circle appeared in Kyiv, and a small group of Jewish actors in Chernivtsi [12]. The Yiddish singer Saul Liubimov performed in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odesa in 1955 [13].

The changes in the national-cultural policy of the authorities of Soviet Ukraine that occurred in the late 1950s and the first half of the 1960s were not very significant (for example, the demonstrative renaming of a street in a city with a large Jewish population to “Sholom Aleichem Street”); from time to time, tours were arranged for artists from other republics who performed songs or monologues in Yiddish (Hanna Guzik, Z. Shulman, Nekhama Lifshitz, B. Khaitovsky, and others), but in Ukraine itself, only Sidi Tal was allowed to perform with a similar repertoire, and even then, only rarely [14].

Basically, all statements by the Soviet leadership about the revival of Jewish culture in the USSR were aimed at the West, where the Kremlin sought to create a positive image for itself, which had been considerably tarnished after the exposure of Stalin’s personality cult.

In Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv, Lviv, Odesa, Vinnytsia, and other cities, the first Zionist circles began to emerge spontaneously. As a rule, they were created around a single family, where one of the members knew Hebrew, had been to Palestine before the revolution, or was an old Zionist who had been imprisoned under Stalin for his beliefs. Their activities were initially limited to jointly celebrating Israel’s Independence Day, studying Jewish history, and discussing information about the country obtained through various channels. Sometimes they managed to meet with Israeli diplomats. As early as 1955-1956, the first wave of arrests affected members of such groups. About 100 people were arrested [15].

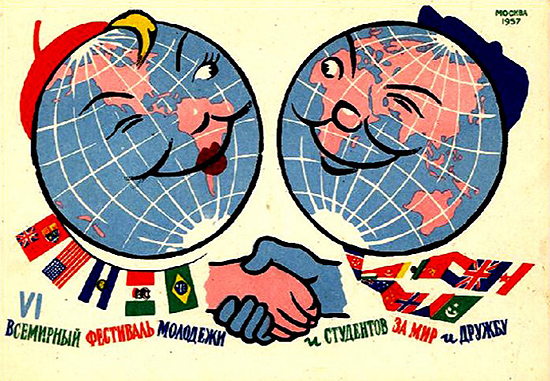

A special impetus to the Jewish national revival and the revival of Zionism in the USSR was given by the VI International Festival of Youth and Students, which took place from July 28 to August 11, 1957, in Moscow [16]. The country slightly lifted the Iron Curtain to the rest of the world for the first time.

During the festival, Soviet Jews were able to openly meet with members of the Israeli delegation for the first time, who, unlike Israeli diplomats, openly and freely made contact with them. Many of them had specifically joined the delegation to meet with Soviet Jews. After the festival, the number of Zionist groups increased, especially among the youth. Later, Hebrew began to be taught in these circles.

The arrival of the Israeli delegation at the Festival of Youth and Students caused a real stir among Soviet Jews. Many sought personal meetings with the Israelis, spoke of their desire to emigrate, and asked for materials about Israel and Hebrew textbooks. However, the Soviet authorities did not forgive their citizens for unauthorized contacts with foreigners, especially with citizens of Israel. Dozens of Zionists paid for their contacts with the Israeli delegation and members of the Israeli embassy, and for distributing materials about Israel, with their freedom, among them Baruch Vaisman, Meir Drezinin, Hirsh Remenik, and Yakiv Fridman in Kyiv.

Despite the tense atmosphere, a large Israeli delegation was still allowed to participate in the international youth festival. Soviet Jews greeted the members of the Israeli delegation with warmth and enthusiasm, which testified to their deep attachment to the reborn Jewish state. Moscow Jews and thousands of others who had specially come from the provinces enthusiastically applauded the Israelis wherever they appeared, begging for Israeli postcards, pins, matchboxes, brochures, and stamps as “souvenirs”; many invited the delegates to their homes and sent them touchingly friendly notes.

During the festivities themselves, the Soviet police did not intervene. But afterward, Soviet Jews paid dearly for this outburst of pro-Israeli feelings. As soon as the foreign delegations left, thousands of participants in the pro-Israeli demonstrations were dismissed from their jobs under various pretexts; many of them were arrested and exiled. About 120 such exiles were sent to Vorkuta for terms of 15 to 17 years.

Israeli diplomatic representatives repeatedly encountered various kinds of trouble. The attaché of the Israeli Embassy, Eliahu Hazan, was arrested in Odesa on September 7, 1957, and after a 26-hour interrogation, was expelled from the Soviet Union. In July 1960, the trade union organ *Trud* accused embassy employee Yakov Kelman of distributing “anti-Soviet literature”—in particular, the monthly *Vestnik Izrailya* (Israel Herald), published in Russian in Tel Aviv. A year later, the first secretary of the embassy, Yaakov Sharett, was accused of espionage and forced to leave the Union immediately [17].

Thus, effectively only antisemitism remained the sole factor of national identification for the Jewish population group. It can be said with a high degree of certainty that if it were not for state and everyday antisemitism in the USSR, assimilation would have become a serious problem for Soviet Jews as early as the 1960s.

In May 1957, an anti-Judaic campaign began in the USSR. It intensified even more in connection with the start of Khrushchev’s general persecution of religion. The beginning of the campaign can be considered the issuance of the secret resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU “On the note of the propaganda and agitation department of the Central Committee of the CPSU for the union republics ‘On the shortcomings of scientific-atheistic propaganda’” dated October 4, 1958. It obliged party, Komsomol, and public organizations to launch a propaganda offensive against “religious vestiges.”

In the “conclusions of the KGB commission under the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR on the content of the Bible-Torah and Jewish prayer books of the Judaic religious ritual” dated February 2, 1959, in addition to the standard denigration of Zionism as a bourgeois-reactionary ideology, it was pointed out the “falsity” of the thesis of Jewish religious literature about the commonality and brotherhood of Jews worldwide, which drives a wedge between the Jewish national minority of the USSR and the socialist nations, and which could push Soviet Jews onto the path of anti-patriotism, instill the thesis of greater commonality with overseas and Israeli Jewish capitalists than with the peoples surrounding them, and turn them away from the path of communist construction [18]. The expediency of banning the publication of the Jewish prayer book was expressed; the head of the propaganda and agitation department of the Central Committee of the CPU, Khvorostianyi, characterizing the Jewish religious literature distributed among Jewish citizens of the USSR as “militantly nationalist,” recommended strengthening atheistic and anti-Zionist agitation to stop the “reactionary” and Zionist propaganda aimed at undermining the friendship of the peoples of the USSR [19].

Accordingly, the number of anti-Judaic publications in the press grew each year [20]. Initially, one might have thought that all this propaganda, undoubtedly instigated by the authorities, was rather the result of the sick imagination of people who had lived their lives under Stalin and remained faithful to the moods and spirit of that time. But it very soon became clear that this was a much more serious phenomenon. The anti-Jewish statements in the Soviet press were partly linked to traditional Soviet anti-religious propaganda. Specially created unions and organizations had been conducting systematic agitation against churches, synagogues, priests, rabbis, and so on for many years. Among the writers who conducted this propaganda in the Jewish sector in the post-war years were the well-known Moisei Bilenkyi, K. Yampilskyi, Mikhail Shakhnovich, Trokhym Kychko, and F. S. Mayatskyi.

It should be noted here that religious Jews treated this propaganda rather calmly. They did not read the books of Shakhnovich, Yampilskyi, etc., and these pseudo-scientific studies with quotes from Lenin and Stalin did not bother them.

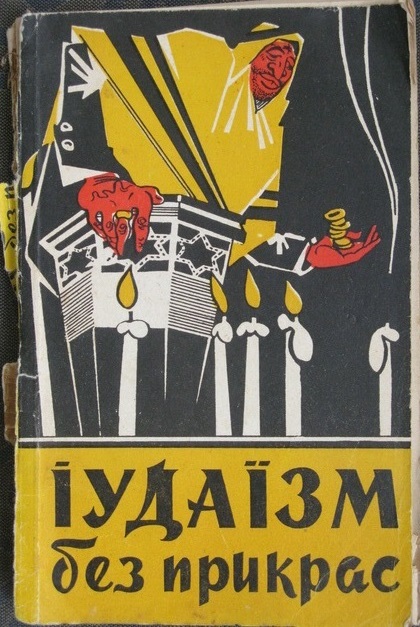

The situation changed from the late 1950s, when Soviet propagandists began to strongly emphasize the organic connection of Judaism with Zionism and at the same time portray Israel as a center of American imperialist intrigues in the Middle East. In 1963, T. Kychko’s book *Judaism Without Embellishments* was published in Ukrainian in Kyiv under the auspices of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR [21]. The cover itself states that “the author of the book reveals to the reader the main essence of the Judaic religion (Judaism)—one of the oldest religions in the world, which has absorbed and concentrated all the most reactionary and anti-human things found in the writings of various religions.” “The Talmud is imbued with contempt for labor and for working people—the common folk... The Talmud has a particularly negative attitude towards the labor of peasants” (p. 40). “One of the commandments of Judaism says ‘thou shalt not steal,’ but at the same time, as Hoshen Mishpat explains—do not steal only from your own, but from others you can steal everything, as stated in the holy scripture... Jehovah gave the Jews all the wealth of the non-Jews” (p. 92). “The morality of Judaism does not condemn hypocrisy and bribery” (p. 93). Kychko spares no space to explain to the Ukrainian reader that Jewish rabbis are essentially engaged in dirty business, fraud, labor exploitation, and are also full of hatred for foreigners—non-Jews. Kychko does not forget the synagogues, where Jews engage in all sorts of disgusting things, and connects all this with Israel and American imperialism. “Speculation with matzah, pork, theft, deception, debauchery—this is the true face of the leaders of the synagogue” (p. 96). “It is impossible to understand the history of the relationship between American capital and Zionism and Judaism if one does not take into account the affairs of the Rockefeller billionaires, who for decades have been trying to seize a part of Palestine—the Negev with its oil deposits... Israel and Zionism with Judaism are seen by American imperialists as forward positions, as a spare tool for shelling the Arab world” (pp. 171-172).

To fully appreciate Kychko’s book, one must see the caricatures that accompany the text. On the cover is a long-nosed Jew with red, bloody hands, in full prayer attire (tallit). All the caricatures, about thirty in number, seem to have been taken by the author from the Nazi propaganda organ *Der Stürmer*.

The Soviet Union had never known a book and propaganda of this nature before. Naturally, the appearance of this book was met with outrage not only among Jews in free countries, but also among broad non-Jewish public circles in Western Europe and America. The book particularly shocked those liberal intellectual circles who had previously considered any hint of antisemitism in the USSR to be a manifestation of the Cold War.

Even communists protested. The New York communist Jewish newspaper *Mornign Frayhayt* stated in an editorial that Kychko’s book “reminds everyone of the well-known caricatures of Jews in antisemitic magazines” (New York, March 24, 1964). The Jewish communist newspaper in Paris, *Naye Prese*, published an open letter sent to the Soviet news agency “Novosti,” demanding that they “inform us about this pamphlet... whether such a book really appeared in Kyiv, and if it did, what the Soviet authorities think and are doing against such antisemitic propaganda” (Paris, March 16, 1964). The chairman of the British Communist Party, J. Gollan, openly called Kychko’s book antisemitic. In Canada, the left-wing weekly *Vokhenblat* published an article titled “We are shocked” (March 19, 1964). Protests against Kychko’s book also appeared in *L'Humanité* in Paris (March 24, 1964), in the left-wing Italian newspaper *Paese Sera* (March 25, 1964), in the communist newspaper *L'Unità* (March 29, 1964), as well as in England, Sweden, and other countries [22].

Interestingly, the Kremlin was perfectly well-informed about the international scandal caused by Kychko’s antisemitic book. Officials of the CPSU Central Committee apparatus in official memorandums openly expressed the harm the brochure had caused; the international protest against “Judaism” caused particular negativity; Central Committee employees acknowledged the falsity of the assertion that the Judaic religion was the root of Jewish “bourgeois nationalism”—Zionism.

The scandal reached a diplomatic level. For example, instructions to Soviet ambassadors in Paris, London, Bern, Tel Aviv, and Vienna contained instructions on how to justify to “friends of the USSR” the “certain inaccuracies” in Kychko’s book, which, they claimed, had already been criticized in publications of the periodicals *Sovetskaya Kultura* and *Izvestia*. In a note from the secretaries of the Central Committee, L. Ilyichev and B. Ponomarev, dated March 28, 1964, it was recommended to send materials criticizing certain provisions of “Judaism” to “fraternal CPs”; to distribute the relevant articles from *Izvestia* and *Sovetskaya Kultura* abroad; and to draw the attention of party bodies, including the censorship office, to the issue of strengthening control over the content and ideological orientation of anti-religious literature.

However, Moscow’s official line was diametrically opposite. The Soviet media angrily condemned the “malicious uproar” and “broad anti-Soviet campaign” being waged over Kychko’s work, which, in principle, justly criticized Judaism (especially for its “connection” with Zionism) [23]. In short, the Kremlin’s position on “Judaism Without Embellishments” stemmed from the anti-religious campaign that was being conducted at that very time; the international outrage and Israeli pressure were, rather, an additional, aggravating factor.

Moscow initially even tried to defend the publication of “Judaism Without Embellishments,” but then, under pressure from communist circles in the West, tried to smooth over the impression made by Kychko’s book, though no one, of course, dared to publicly admit that a book of essentially Hitlerite character had been published in the Soviet Union. However, Kychko’s book, submitted for review to the ideological commission of the CPSU Central Committee, was declared erroneous and poorly prepared. The commission pointed to “a number of erroneous statements and illustrations... which could offend the feelings of believers and be interpreted in the spirit of antisemitism.” However, Kychko himself was not touched [24].

One of the manifestations of the campaign against Judaism was the mass closure of synagogues. In total, from 1957 to 1966, over 100 synagogues and prayer houses were closed in the USSR. By the end of this period, only 62 synagogues remained in the country. Moreover, in cities such as Chernivtsi, Vinnytsia, and Lviv, no synagogues were left at all.

These attacks were particularly fierce in Ukraine, where arrests of religious Jews even began on the long-forgotten charges of “Zionist propaganda.” The “propaganda” consisted of several Jews saying “Next year in Jerusalem” in a synagogue on Passover. The authorities were especially afraid of Soviet Jews being “infected” with Zionist ideas, and consistently fought against “Israeli influence” in synagogues [25].

Legally, the repressions were justified by Article 227 of the new Criminal Code of the RSFSR, which provided for 5 years for “infringement on the person and rights of citizens under the guise of performing religious rites.” While only 5 synagogues were closed in 1958-1959, 31 were closed in 1960-1961.

In Ukraine, the Jewish communities of Poltava, Stalino, Kremenchuk, Chernihiv, Mykolaiv, Uman, Chernivtsi, Bila Tserkva, Kherson, Cherkasy, Zhmerynka, Zhytomyr, and other cities were deprived of state registration. But the persecution was most severe in Lviv, where Jews from the management of the local synagogue—G. Kantorovich and A. Sapozhnikov—were among those arrested for speculation. They were accused of using the synagogue as a “black market.” After a visit by American and Japanese diplomats on April 10, 1962, a decree was issued four days later by the executive committee of the Lviv region to de-register it for “admitting Israeli diplomats onto the territory” [26]. On October 17, 1962, the Council for Religious Affairs and Cults (CRAC) issued an order for its closure [27].

Synagogues were closed not due to a lack of congregants, but by order of the authorities. At the same time, local authorities banned minyans, i.e., prayer services that believers organized in private apartments, for example, in Kharkiv and Odesa.

This far from complete list reveals the true picture of the situation of synagogues in the Soviet Union. Synagogues were closed by local authorities under various pretexts, and in most cases without the possibility of appeal. Often, under the pretext of a decreasing number of believers, local authorities requisitioned prayer houses for Red Army clubs, the Communist Youth League, etc.

In a number of cities, the liquidation of synagogues was preceded by a press campaign—newspapers wrote that synagogues had turned into centers of the black market, drunkenness, and anti-Soviet propaganda. In parallel with this, there was a campaign of disinformation of the world community on the problem. The Soviet government’s committee on religious affairs reported that in 1960, 400 synagogues in the Soviet Union served half a million Jewish believers. Around the same time, the Soviet government officially informed the UN that there were 450 synagogues in the USSR. “The Soviet Mission Today,” the weekly bulletin of the Soviet embassy in Vienna, reported in the same year, 1960, that religious services were held in 150 synagogues throughout the Union.

Sofia Frey, from the editorial board of the only Soviet Yiddish-language newspaper, *Sovetish Heymland*, responding to a critical article in the New York *Life* (December 7, 1959), reported that synagogues existed in the Zhytomyr region (6), Poltava region (3), Vinnytsia region (5), Khmelnytskyi region (3), Chernihiv region (3), as well as in Odesa, Kherson, Mykolaiv, Berdychiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Kirovohrad, etc.

All the above figures were published in 1960, and three years later, the magazine “U.S.S.R.”, based on information received from the Moscow rabbi Y. L. Levin, reported that there were only 96 synagogues in the USSR; by 1965, 97 synagogues were functioning in the Soviet Union [28].

In 1966, only 62 synagogues remained in the USSR (8 in the Ukrainian SSR). Prayer institutions were closed in Lviv, Zhytomyr, Zhmerynka, Chernivtsi, Vinnytsia, Novoselytsia, and Rakiv [29].

According to G. V. Kostyrchenko, 28 out of 41 synagogues in Ukraine were closed—the largest absolute figure in the USSR. In the Union as a whole, out of 135 synagogues operating in 1958, 90 remained by 1965, i.e., 66% [30].

An offensive was waged against the last legal organizational stronghold of Jewish tradition—the registered Jewish communities; in 1959-1962 alone, their number in the Ukrainian SSR decreased from 41 to 15. Religious Jews had to gather for “underground” minyans, but such gatherings were often dispersed with the help of the police, whose officers threatened the mostly elderly congregants. The local and republican press took part in the persecution of believers: for example, in June 1959, *Kyivska Pravda* “branded with shame” the participants of a minyan in the town of Bohuslav, Kyiv region: I. Babich, M. Stanivskyi, I. Gomberg, I. Dychynskyi, and others. Nevertheless, spiritual resistance to the regime continued, and in Western Ukraine, attempts were even made to recreate an illegal network of Jewish education: in Uzhhorod, in the village of Serednie Vodiane in the Rakhiv district of the Zakarpattia region, and in other places, secret cheders were discovered by state security organs. Private teaching of Hebrew and even Yiddish was not allowed; Jewish children attended only Ukrainian and Russian schools (the latter were considered more prestigious).

In addition to closing synagogues, in 1959, the USSR began to practice restrictions on the baking of matzah. A group of Jews who were making matzah was arrested. In 1961, the production of matzah in bakeries at communities was banned everywhere (including in the Ukrainian SSR), except for Moscow, Leningrad, Central Asia, and Transcaucasia.

In March 1962, the Central Committee of the CPSU gave instructions for the complete liquidation of matzah production. In 1963, the bakery in Kyiv was closed, but underground production of this product intensified in Ukraine; parcels from the USA and Israel also increased [31]. However, parcels with matzah from abroad were often returned by the authorities [32].

At the same time, the authorities hindered the sending of matzah, as well as other religious products and items, from abroad to the USSR. In 1964, 20 tons of matzah sent from the USA were detained at Soviet customs. Articles appeared in the press, including some written by Jews, stating that sending items of Jewish religious worship and matzah from abroad to the Soviet Union was a form of ideological subversion [33].

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a campaign was carried out to close Jewish cemeteries. The campaign took place in Kyiv, Rivne, and other cities [34].

Thus, all these actions by the authorities objectively contributed to the assimilation of Soviet Jews, since distracting Jews from Judaism was a powerful assimilationist factor.

The antisemitic campaign of the Khrushchev period, in addition to the closure of synagogues and cemeteries, led to two other phenomena that were clearly not anticipated by its initiators: a hidden protest from well-known representatives of the intelligentsia and a spontaneous protest from the Jews themselves, which resulted in the creation of a whole series of underground Zionist circles and groups, and the revival of the underground study of the Hebrew language.

A significant event in the literary and public life of the country was the publication of Y. Yevtushenko’s poem “Babi Yar” in *Literaturnaya Gazeta*. The poem was published on September 19, 1961, and was dedicated to the twentieth anniversary of the mass shooting of Jews. The author repeatedly recited this poem at various events. In it, Yevtushenko was the first to state directly that the Jewish population of Kyiv had been annihilated at Babyn Yar. This contradicted the official version of the authorities about the destruction of Soviet citizens of various nationalities there. A year later, composer D. Shostakovich wrote his Thirteenth Symphony based on Yevtushenko’s poem—the libretto for its first part was written based on the poem [35].

“Babi Yar” resounded as a powerful and sincere voice of protest; its lines tore through the dense web of antisemitism that had enveloped Soviet public consciousness. The poem became iconic, and many disputes arose around it. Jews began the fight to install a memorial monument at Babyn Yar. Fifteen years later, in 1976, it was finally installed. But there was no mention on it of the mass shootings of Jews.

Yevtushenko’s poem found a wide response among Jews all over the world, especially in Israel. On March 8, 1963, Khrushchev spoke of the “revival of the Zionist rat” in the USSR because of the uproar that “Babi Yar” caused on the international stage and the sympathy of the Israelis for it [36].

In the “romantic” period of the revolution and Soviet power, Zionists were considered enemies because their activities distracted Jews from the urgent tasks of the revolution and the construction of socialism in the USSR, but in the 1950s-60s, Zionism, although still defined as an “accomplice of imperialism,” worried the authorities for another reason.

Obviously, the goal of Soviet Zionists was the departure of Jews from the “best country in the world—the Land of the Soviets,” a kind of “paradise on Earth,” which Soviet propaganda, with varying success, had been convincing the international community of for decades. The logic of the authorities was this: if someone flees from such a country, then he is either insane, or Soviet propaganda is lying. It was difficult to convince the whole world that people of Jewish nationality who share Zionist ideas are insane. But it was impossible to admit that the Soviet propaganda machine was lying.

Therefore, all Zionists were recorded as agents of foreign enemy intelligence services, who deliberately duped Soviet Jews with the spirit of Zionism in order to undermine the USSR’s efforts to promote socialism and the Soviet way of life.

However, the process had already been launched. In Zionist circles, the teaching of Hebrew became widespread. Even after the 1957 youth festival, the exchange of information between Soviet Jews, on the one hand, and Western countries and Israel, on the other, intensified.

The Israeli embassy also stepped up its information activities, providing activists of Zionist groups with books, newspapers, etc. [37].

Some contacted representatives of the embassy, despite the fact that it was risky: the Israeli delegation was under constant surveillance. At meetings, diplomatic mission staff provided printed materials of a cultural and historical nature, and Hebrew textbooks, which local Jews had been deprived of for many years. Soviet Jews could convey requests and wishes, for example, “to broadcast Israeli radio programs in simpler Hebrew so that more people could understand them.”

Members of the Israeli delegation received instructions from their government to maintain contact with the Jewish population. If before February 1953 (before the break in diplomatic relations) the Israelis visited the synagogue only on major holidays, now they went there every Saturday. In addition, there was an opportunity to visit different cities, sometimes in their own cars with an Israeli flag on the hood, which invariably attracted the attention of local Jews. Wherever the Israelis appeared, they tried to visit the local synagogue. This most often happened in Odesa, where Israeli ships loaded with citrus fruits arrived, but diplomats also visited Kyiv, Kharkiv, and many other cities.

At the Ural Polytechnic Institute (Sverdlovsk), a circle gathered around Ilya Voitovetskyi (1954). The young man grew up in the Urals, where his parents had come from Ukraine in 1941 as evacuees. He later recalled: “We had many Jews from Ukraine... They came to Sverdlovsk because in Ukraine they had no chance of getting a higher education. These guys were closer to tradition than in Russian cities” [38].

Zionist groups and circles reappeared in the country: in Odesa—that of Iosif Khorol and Oleksiy Khodorovskyi, in Kharkiv—that of Yefim Spivakovskyi. The state security organs caught the members of these groups and sent them to camps for terms of 10 to 25 years.

At the same time, even during the “Thaw,” the Soviet authorities, adhering to old stereotypes, viewed the increased socio-political activity of Jews as attempts to restore the “nationalist underground.”

In the spring of 1956, the state security organs arrested young Kyivans of Jewish origin A. M. Partashnikov, A. Sh. Feldman, M.-R. Sh. Gartsman, and the Russian V. P. Shakhmatov. They were accused of having united in the “League of Democratic Revival” back in 1951, and in early 1956, of creating the “Socialist Union for the Struggle for Freedom.” The participants distributed leaflets condemning the de facto ban in the USSR on freedom of speech, thought, creative initiative, neglect of civil rights, etc.

In June 1956, they were convicted in Kyiv for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” The members of the group, A. Partashnikov (N. Prat), A. Feldman, M. Gartsman, and their Russian comrade V. Shakhmatov, had previously formed a circle in which issues of liberalization of the regime were discussed, including the rejection of state antisemitism, and they also distributed leaflets of a corresponding content. The court sentenced them all to various terms of imprisonment from 1 to 6 years [39]. In the autumn of 1956, Kyivan K. Sternik, who had committed a similar “crime,” found himself behind bars.

In Kyiv, there was a Zionist circle grouped around B. Vaisman and Ts. Remennik. Hundreds of Soviet Jews from different cities took part in one form or another in the meetings of the reviving Zionist groups and circles. The first wave of arrests in 1955-1956 affected about a hundred people, but most were later released. The activists were charged under articles “58-1a” (treason), “58-10” (possession of nationalist literature for the purpose of conducting anti-Soviet propaganda), “58-11” (belonging to an anti-Soviet organization) and sentenced to imprisonment for terms of 3 to 10 years.

At the beginning of 1957, Baruch Vaisman, Khirsh Remennik, Meir Draznin, and Yakiv Fridman were arrested in Kyiv and accused of Zionist activity and of possessing and distributing anti-Soviet materials. On July 23, 1957, a trial of a group of “secret Zionists” took place in Kyiv, who back in 1955 had “met with a representative of the Israeli embassy” who supplied them with illegal literature. The defendants who appeared before the court were elderly people. Since 1952, Vaisman had kept a diary about the life of Jews in the USSR, the entries of which were transmitted through the Israeli embassy by agents of the special service “Nativ” to the Israeli press and to the West. Draznin was sentenced to ten years in prison, Remennik to eight, and Vaisman and Fridman received five years each (for listening to Israeli radio, slandering the Soviet Union in letters to relatives in Israel, etc.). But in 1960, Vaisman was pardoned [40].

In Odesa, Zolia Kats was arrested and after a year of investigation was sentenced to eight years in prison (“hostile nationalist propaganda”) [41]. Thus, in 1955-1957, members of a group from Kyiv and Odesa were arrested and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment (from 2 to 10 years).

Simultaneously with the start of the arrests of Jewish activists, three employees of the Israeli embassy were expelled from the Soviet Union [42]. The authorities closely monitored the correspondence of Moscow Zionists with Israelis [43]. From 1957, the formation of anti-Zionist propaganda as a separate direction began in the USSR (in accordance with the resolution of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the CPSU of October 3, 1957) [44].

Thus, the measures to suppress the Zionist movement were harsh but had a limited character.

Against this background, old and new groups of nationally oriented Jews continued to function in Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other cities. They met to discuss events in Israel, to study Jewish history and Hebrew, and to disseminate knowledge that contributed to the awakening of Jewish national consciousness.

The importance of Jewish “samizdat” increased sharply. The Moscow group of Shlomo Dolnik and Ezra Morgulis, which maintained ties with similar groups in Riga, Kyiv, and other cities, was engaged in the publication and distribution of samizdat.

In the second half of the 1950s, Jewish samizdat appeared as a separate direction. The reproduction of samizdat literature in conditions where access to duplicating equipment was carefully guarded by the state was not an easy or safe business. One of the most active distributors of Israeli literature in the 1960s was a former member of the Zhmerynka Zionist group, Meir Gelfond, who had moved to Moscow. Samizdat published the poems of H. N. Bialik, the feuilletons of Vladimir Jabotinsky, the historical works of Semyon Dubnov, as well as the books “My Glorious Brothers” by Howard Fast and “Exodus” by Leon Uris, which were secretly translated into Russian and became a kind of Bible for a whole generation of Zionists in the USSR.

The authorities’ repressions were also directed against Jewish samizdat, which had just emerged as an independent force during the “Thaw.” In the 1950s, the journalist Ya. Eidelman (father of the famous writer N. Eidelman)—a Zionist by conviction—distributed articles in samizdat about the 1956 Sinai Campaign, about Hannah Szenes, as well as the work “A and B” (The Foundations of Zionism). The leader of the Zionist circle in Moscow, E. Morgulis, released in samizdat a series of summaries of Israeli radio broadcasts, the essays “The State of Israel,” and “A Review of the Life of Jewish Communities” by M. Bergman [45].

Bergman was one of the first to translate Leon Uris’s novel “Exodus” into Russian (1960-1961). This translation, with a volume of 60 and 150 pages of typewritten text, was distributed in dozens of copies to many cities of the Soviet empire. It had a huge impact on the awakening of Jewish national self-awareness and the struggle for emigration to Israel.

Bergman also translated the book of the Polish professor, the Jew Bernard Mark, “The History of the Warsaw Ghetto,” and the most important work on the history of Zionism, the autobiography of the first Israeli president, Chaim Weizmann, which contains information about the Zionist congresses, the struggle for the “Balfour Declaration,” and other materials on the history of the Jewish state. This book was later published in two volumes by the “Biblioteka Aliya” publishing house under the title “In Search of a Way” [46].

In 1962-1964, Ezra Morgulis wrote a two-volume work, “A Review of the Life of Jewish Communities,” which numbered about 600 typewritten pages and provided a brief description of the state of Jewish communities in the diaspora, told about their culture, ties with Israel; it also detailed the situation of Soviet Jews, oppressed by the antisemitic policy of the authorities with the aim of complete assimilation.

Even earlier, in 1960, Morgulis completed the monograph “The State of Israel,” about 230 pages long, typed on a typewriter, which presented information about the agriculture, culture, science, and Armed Forces of Israel from a Zionist perspective and in a popular form. This book reached Palestine in the early 1960s.

During the years of Ezra Morgulis’s circle’s activity (1960-1966), about 40 samizdat works were translated and printed [47].

In general samizdat, starting from the late 1950s, there was a whole series of publicistic works, as a rule by non-Jewish authors, describing such phenomena as the fight against cosmopolitanism, the “Doctors’ Plot,” antisemitism, and the issue of the de facto banned Jewish culture. The report “On the Problems of Antisemitism in the USSR” by B. Polevoy, the editor of the magazine “Yunost,” who first raised this issue in 1957, was distributed in samizdat, as was the speech of P. Blyakhin at the Union of Soviet Writers, in which he called on the writers’ organization to distance itself from antisemitism.

A. Amalrik in his work “Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?” (1964) argued that imperial states like the Soviet Union build their policy on the ideology of struggle against external and internal enemies. Such an external enemy could be, for example, American imperialism. Jews, however, for at least all the post-war years of Soviet history, played the role of the internal enemy, on which a part of Soviet domestic and even foreign policy was based.

Directly in Jewish samizdat, one can distinguish artistic and political directions. The latter can be divided into two parts. The first concerned Israel: starting from the late 1950s, Israeli radio broadcasts were recorded and distributed in samizdat. Jewish samizdat was, naturally, also fueled by the problems of Soviet Jews.

The most active centers of such activity in Ukraine were Kyiv, Odesa (the group of G. Shapiro), and Kharkiv. In 1966, the speech of I. Dziuba at an unauthorized rally in Babyn Yar was very widely distributed [48].

In parallel with the repressions, their legal basis was also being adjusted. On December 25, 1958, the USSR law “On Criminal Responsibility for State Crimes” was updated: the authorities removed the black mark of “enemy of the people,” and the maximum term of imprisonment was reduced from 25 to 15 years. Article 11 of the law for the first time provided for real punishment for ethnic discrimination (in hiring, for example), aimed at implementing the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” of December 10, 1948; the same applied to Article 74 of the new Criminal Code.

The new criminal code of the RSFSR was put into effect on January 1, 1961. Under the old Criminal Code of the RSFSR of 1926, Article 58-10 provided for 10 years in camps (anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation); in the new version of the Criminal Code, it was 3 years for ordinary cases and 7 years with confiscation of property “using religious and national prejudices,” and under the similar Article 70 of the new Criminal Code, people were sent to corrective labor colonies for a term of six months to 7 years, or to exile from 2 to 5 years (without “prejudices”). But for a relapse, they were already given up to 10 years. The peak of convictions under this article was in 1957-1958, after which there was a certain relaxation [49].

Against samizdat activists, the infamous Article 58 was used until 1962, one of its sub-clauses being “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” This article was applied, in particular, to the creators of the magazines “Sintaksis” and “Feniks.” After 1961, Article 62 appeared in the criminal code—“Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” (up to 7 years of imprisonment and 5 years of exile) [50].

The authorities were concerned about the growth of the Zionist movement, but they had to reckon with pressure from prominent members of left-wing movements in the West, including representatives of the communist parties of Italy, France, and Canada.

One of the main factors limiting the rights of Jews was the ban on their emigration. Having restored diplomatic relations with Tel Aviv in July 1953, Moscow did not want to raise them to the level of the late 1940s. The possibility for Jews to emigrate to Palestine decreased. Thus, while 8,163 Jews left the USSR in May 1948-1951, only 13,743 people left in 1952-1960 [51].

The “Thaw” was marked, among other things, by new attempts at Jewish emigration to Israel (53 people in 1954, 106 in 1955, and 753 in 1956). Mostly elderly people left under the pretext of “family reunification.” After the restoration of Soviet-Israeli relations, a thin trickle of Jewish emigration to Israel began. Accordingly, 54 exit visas were issued in 1953, 106 in 1955, and 753 in 1956 [52].

By the autumn of 1956, the number of applications for emigration to Israel had significantly increased: while in 1951 official authorities received only one such application, in 1955 there were 315, and in the first nine months of 1956—1,260. In Ukraine, Jewish refuseniks appeared: the authorities gave a negative answer to 616 of the 774 applications considered in 1956.

Emigration, which also affected Germans and Spaniards, was carried out under two categories: repatriation and family reunification. This meant that the Soviet leadership was in no way ready to recognize free emigration. It was only prepared for the return of foreign nationals who found themselves on Soviet territory as a result of wars and social upheavals, and for the reunification of separated families. With regard to Jews, each case was considered on an individual basis with the accumulation of serious obstacles and was accompanied by arbitrary decisions and an extremely uncertain outcome. Almost all those who emigrated during that period were pensioners who were reunited with their children in Israel. The emigration trickle was completely stopped in October 1956 as a “punishment” for Israel for its aggression against Egypt [53].

The issue of Jewish emigration was perceived at the highest level as a serious political problem. In a KGB report to the Presidium of the Central Committee of the CPSU on the content of letters from people who had left for Israel, dated December 31, 1957, the selection of messages from former Soviet citizens for propaganda purposes was extremely biased, consisting entirely of negative assessments. The corresponding resolution prepared proposed helping some to return and speak out in the press [54].

In a proposal to the Commission of the Central Committee of the CPSU on issues of ideology, culture, and international party relations, it was reported that in 1957, 1,185 applications were received from citizens of Jewish nationality with a request to leave for permanent residence in Israel. By a decision of the commission, only 100 people were given permission to emigrate [55].

In accordance with the resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU of October 3, 1957, leading Soviet newspapers, including national republican ones, published materials of an anti-Israeli and anti-emigrant nature. The Kremlin also planned to hold a press conference of Jews who had returned from Israel—former Soviet citizens—in the capitals of the USSR republics, including Kyiv; to publish relevant propaganda brochures; and to send prepared groups of tourists to Israel; responsibility for implementation was placed on the regional party committees of the CPSU, including the Kyiv one [56].

In 1960, 60 people left on Israeli visas, in 1961—202, in 1962—184, in 1963—305, and in 1964—537. In total, during the Khrushchev decade (1954-1964), 2,418 Soviet Jews emigrated to Israel [57] (according to Israeli publicist M. Shterenshis—only about 4,646 people in 1961-1964 [58]). According to the Jewish encyclopedia, in 1954-1958, 1,090 Jews emigrated from the USSR, all to Israel; in 1959-1969—9,125, also all to Palestine [59].

Thus, from the late 1950s, the confrontation between the two states on the Jewish question in the USSR and the problem of repatriation, in particular, began to grow. As declassified documents show, the KGB paid great attention to the issues of emigration to Israel, the exposure of “Zionist propaganda,” the “subversive” agitation activities of the Israeli embassy in Moscow, etc. [60]. In the understanding of the Israelis, the problem of repatriation concerned not only the Soviet Union itself, but also the countries of “people’s democracy” [61]. Tel Aviv developed considerable activity in this direction, gradually involving foreign states in the issue and bringing it up for international discussion [62]. This topic became one of the main factors in the deterioration of Soviet-Israeli relations, which ended with the severance of official diplomatic contacts in June 1967.

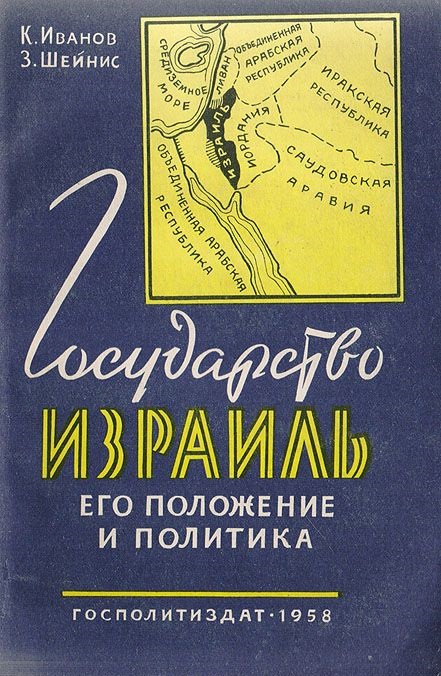

In Soviet literature and press, Israel and Zionism in all its shades were described as a real monster. A special brochure by K. Ivanov and Z. Sheinis, “The State of Israel, Its Position and Policy,” published in 1958 by Gospolitizdat, is full of numerous distortions. The brochure went through two editions and sold 150,000 copies. There is no shortage of “inaccuracies” in the chapter on Israel in the work of Yuri Basistov and Innokentiy Yanovsky, “The Countries of the Near and Middle East,” published in the same year in Tashkent. The Soviet press, both metropolitan and provincial, invariably described Israel as an “obedient tool in the hands of American and Anglo-French imperialists” (*Lvivska Pravda*, December 14, 1958). The Israeli reality is invariably painted in the darkest colors, and Soviet Jews are persistently told that the concept of the “Promised Land” is nothing more than a reactionary mirage. Grigory Plotkin, who visited Israel in July 1958 with a group of 12 Soviet tourists, even wrote a special drama on this topic, “The Promised Land,” which turned out, however, to be so talentless that even the Moscow magazine *Teatr* harshly criticized it.

Soviet newspapers, as if by special order, abound with screaming headlines on the same theme: “No, this is not paradise!” exclaims the author of an article in *Vechernyaya Moskva* on January 4, 1960; an article in the August issue (1960) of the magazine *Ogonyok* is called “A Groan from Paradise”; *Sovetskaya Moldavia* (in its issue of September 30, 1960) persuades its readers: “Do not believe the fables about an Israeli paradise”; in the Moscow political weekly *Novoye Vremya* (January 20, 1961), Zinovy Sheinis insists that “Israel has not become a paradise for the working people—the prophets of Zionism have deceived them.” This monotonously persistent exposure of the “mirage of an Israeli paradise” undoubtedly testifies to the fact that the attraction to Israel had become widespread in Soviet Jewry and that if emigration to Israel had been allowed, hundreds of thousands would have taken advantage of this opportunity.

As early as 1956, Khrushchev told the American sociologist Jerome Davis: “I am convinced that the time will come when all Jews who wish to move to Israel will be able to do so.” Khrushchev gave a similar assurance in 1958 to the president’s wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, and a year later to a group of American veterans of World War II.

As is known, one of the possible forms of legalizing Jewish emigration to Israel is “family reunification,” i.e., allowing parents, children, brothers, and sisters to join their relatives in Israel. When asked at a press conference in Vienna whether the Soviet government approved of such a procedure, Khrushchev replied that no such petitions had been received from Soviet citizens and that, on the contrary, many Russian Jews in Israel were now petitioning to return to the Soviet Union. However, Golda Meir, the Israeli Foreign Minister, established that at that time, Soviet Jews had submitted 9,236 requests for permission to go to their relatives in Israel. The vast majority of such petitions remained unanswered. *Vestnik Izrailya* printed an excerpt from a touching letter from a 58-year-old widow to her only daughter in Israel, who, at her mother’s request, had sent her three invitations: “My dear, beloved children. I must inform you of my great sorrow, that I have again been refused permission to travel to you. Now what should I do? I don’t know how I can write to you: my hands are trembling and my heart is barely holding on inside me... My dear, golden, native, beloved daughter, forgive me for writing such a letter. I didn’t want to cause you grief, but what can I do.”

Thus, four decades of Soviet rule did not lead to the eradication of the national consciousness of the Jewish minority. Even the culturally assimilated younger generation continued to feel its belonging to Jewry, and in the older circles, national traditions remained quite strong and vibrant. Israel became in the minds of broad strata of Soviet Jewry, if not a “paradise,” then a symbol of Jewish dignity and normal national life [63].

Meanwhile, the authorities failed to crush the Zionist movement with the arrests of 1957-1962. An important form of strengthening the national self-awareness and Zionist education of Soviet Jews became the mourning rallies held at the sites of mass shootings during World War II—at Babyn Yar (Kyiv) and Drobytskyi Yar (Kharkiv). The participants of the rallies fought for the right to install memorial signs that would clearly indicate that the victims were Jews, and not just “peaceful Soviet citizens,” as the authorities demanded [64].

As early as 1954, on the initiative of war invalid A. B. Kagan, after long petitions, the reburial of Jews shot in Drobytskyi Yar was carried out, and an obelisk was erected with the inscription: “To the victims of fascist terror” (without the word “Jews”). From time to time, the persecution of believers resumed; the underground religious community under the leadership of Y. Ioffe was forced to change its premises for prayers 19 times during the 1950s-1980s [65].

In the early sixties, a campaign began in the Soviet Union that stirred public opinion in the West—the fight against economic crimes. Among those convicted in these trials, almost exclusively Jewish surnames flickered. When information leaked to the West in July 1961 that, contrary to the criminal code, people were being given the death penalty for economic charges (the death penalty was provided only for treason, espionage, sabotage, terrorism, banditry, and premeditated murder with aggravating circumstances), it caused a storm of indignation [66].

As early as the spring of 1960, a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR was issued on transferring economic crimes from the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the jurisdiction of the KGB, and on May 5, 1961—on the application of the death penalty for embezzlement on an especially large scale [67]. In July 1961, the campaign against economic crimes intensified and continued until March 1963. On February 20, 1962, a decree of the Supreme Soviet was issued “On strengthening criminal liability for bribery,” up to and including execution by firing squad with confiscation of property [68].

In total, in 1960-1966, 1,061 people were brought to criminal responsibility in the USSR for illegal currency transactions, while at the same time, in 1961-1967, 497 Jews were convicted, meaning that Jews made up almost half of all those repressed [69]. Of the 163 Jews sentenced to the supreme penalty in the early 1960s for economic crimes, 80 were executed in the Ukrainian SSR [70]. In 1961-1964, 79 Jews were executed in the Ukrainian SSR (while in the RSFSR—only 39). The number of people of other nationalities among those executed was incomparably smaller [71].

The trials were widely covered in the press, even in local newspapers (for example, *Zakarpatska Pravda* on December 21, 1963, reported on workshop operators-rabbis and currency speculators-Zionists) [72]. In 1962-1964, trials against underground workshop operators and corruption took place in Lviv in the Ukrainian SSR. The local synagogue in the capital of Western Ukraine was declared a hotbed of illegal currency transactions and speculation. The apotheosis of the campaign was the case of the Lviv Regional Economic Council, in which Jews again constituted the lion’s share of the convicted [73]. In 1961-1967, 132 Jews were convicted in Lviv for economic crimes, of whom 32 were executed. In Kyiv—129 Jews, 9 were executed [74].

The economic activity of some Kharkiv Jews developed in the conditions of a state monopoly within the framework of the so-called shadow economy. As a result of a campaign launched in 1963 on Khrushchev’s initiative, 6 Kharkiv Jews were sentenced to death for minting gold coins in violation of legal norms, which caused protests from the world community; however, the sentence was carried out for three of the convicts [75].

According to incomplete data published in the West at the time, from July 1, 1961, to July 1, 1963, 140 defendants for economic crimes were sentenced to death; among them were 80 Jews [76].

In a collection of documents edited by B. Morozov, it is indicated that in the period from July 1961 to August 1963, out of 163 people sentenced to death for “economic crimes,” 88 were Jews. In parallel with this, an active antisemitic propaganda campaign unfolded in the newspapers: a large number of articles were published about Jewish currency speculators, embezzlers of state property, etc., including in *Literaturna Ukraina* on 15.10.1963 and 09.10.1964 and *Zakarpatska Pravda* on 29.12.1963 [77].

Given this entire complex of discrimination against Soviet Jews, Israel developed considerable activity on the international stage in connection with the difficult situation of its fellow Jews in the USSR [78]. In addition to Tel Aviv’s efforts, in the early 1960s, various events, organizations, and even entire movements in defense of the Jews of the Soviet Union began to emerge in Western European and North American countries. Thus, on 15.09.1960, the first international conference in support of Soviet Jews was held in Paris. In 1963, Elie Wiesel’s book “The Jews of Silence” was published in the USA. On 12.10.1963, the “Council on Soviet Anti-Semitism” was created in Cleveland (USA) with the participation of Louis Rosenblum, the future first president of the all-American organization “Union of Councils for Soviet Jews.” On 21.10.1963, a conference on the topic “The Situation of Soviet Jews” was held in New York. The organizer was Moshe Dector. In January 1964, a conference of rabbis was held in Ottawa (Canada) on a similar topic. In April 1964, a symposium on the topic “The Situation of Soviet Jews” was held in Washington. On April 4, the “American Jewish Committee on Soviet Jewry” was created in Washington, and on April 5—the American “National Conference on Soviet Jewry.” On April 29, 1964, the all-American organization “Students for Soviet Jewry” was created, and in December 1964—the Canadian branch of “Students,” headed by Irwin Cotler [79].

The Kremlin leadership was well-informed about this activity. A detailed list of such activities is contained, for example, in a report from the USSR Embassy in Canada, “The Intensification of Anti-Soviet Activities of Reactionary Jewish Organizations in Canada,” dated January 21, 1964 [80].

Thus, the Soviet authorities violated a whole series of articles of the then-current 1936 Constitution with regard to Jews. For example, Article 123 guaranteed the “equal rights of citizens of the USSR, irrespective of their nationality and race, in all spheres of economic, state, cultural, and socio-political life” [81] (persecution of Judaism, refusal of admission to higher educational institutions, etc.). Article 124 established “for citizens the freedom of conscience, the freedom to perform religious rites” (anti-religious campaign, closure of synagogues, ban on baking matzah, etc.). Article 125 guaranteed “freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and rallies, freedom of street processions and demonstrations” (persecution of samizdat, obstruction of synagogue attendance, etc.). Article 126 proclaimed that “the popular masses of citizens of the USSR are guaranteed the right to unite in public organizations: trade unions, cooperative associations, youth organizations, sports and defense organizations, cultural, technical and scientific societies” (persecution of Zionist circles, societies for the study of Hebrew, etc.). Article 127 guaranteed citizens of the USSR “inviolability of the person. No one may be arrested except by a court decision or with the sanction of a prosecutor” (detention and arrests of members of various Jewish organizations by KGB officers); Article 128—inviolability of the home and secrecy of correspondence (surveillance and interception of letters, correspondence of Soviet Jews with each other and with Israelis).

Thus, in the Khrushchev era, Soviet Jews were oppressed in all respects—from the persecution of Judaism to the ban on emigration. Of course, during the Thaw, antisemitism was an order of magnitude weaker than under Stalin, but it was felt very distinctly. The violation of the rights of Jews occurred both in the context of the general anti-legal policy of the Soviet authorities, which affected representatives of all ethnic groups and confessions (anti-religious campaign, ban on samizdat, activities of informal organizations, etc.), and taking into account the foreign policy factor (suspicion of sympathies for Israel and the USA, i.e., potential treason to the Motherland in the conditions of the Cold War, the activity of Jews from these countries in the struggle for the rights of their Soviet brethren). In Ukraine, the discrimination against Jews took on much harsher forms than on average in the USSR. This is explained, on the one hand, by the objective factor of the size of the Jewish population of the Ukrainian SSR in comparison with other union republics (especially in relative terms), the remnants of its rootedness and tradition (the territory of Ukraine was part of the core of Ashkenazi civilization), and on the other hand, by the classic distrust of the imperial center towards the inhabitants of Ukraine, the fear of their disloyalty and the possibility of secession of the most important republic after the RSFSR.

1. Regarding the persecution of Jews in Stalin’s time, see in more detail: Kostyrchenko, G. V. *Stalin's Secret Policy: Power and Antisemitism*. Moscow: Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 2001. 779 p.

2. Kostyrchenko, G. V. *Khrushchev's Secret Policy: Power, the Intelligentsia, the Jewish Question*. Moscow: Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 2012, p. 441.

3. Ukraine. Jews in Post-War Soviet Ukraine (1945–91) / Jewish Confederation of Ukraine.

4. For more details on discrimination in admission to higher educational institutions, see: *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)* / edited by Ya. G. Frumkin, G. Ya. Aronson, A. A. Goldenweiser. New York, Union of Russian Jews, 1968, pp. 362-365.

6. *Short Jewish Encyclopedia*. Vol. 8. Jerusalem, 1996, p. 304.

7. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 176-178.

8. Chapter 13. Soviet Jews: A Group Portrait at the Beginning of Emigration / Yuliy Kosharovsky.

9. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., p. 180.

10. Ukraine. Jews in Post-War Soviet Ukraine (1945–91) / Jewish Confederation of Ukraine.

11. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., p. 267.

12. *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)*. p. 381; *Short Jewish Encyclopedia*. p. 258.

13. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., p. 198.

14. Ukraine. Jews in Post-War Soviet Ukraine (1945–91) / Jewish Confederation of Ukraine.

16. For more on the connection between the festival and the Jewish question in the USSR, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 270-277.

17. *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)*. p. 336.

18. *Jewish Emigration in the Light of New Documents* / ed. by B. Morozov. Tel Aviv, 1998, p. 37.

19. Ibid., pp. 38-39.

20. Regarding Soviet anti-Judaic (in fact, antisemitic) publications, see also: *Short Jewish Encyclopedia*, p. 260.

21. For the scandal associated with the infamous brochure by T. Kychko, see also: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 222-230.

22. *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)*. pp. 367-368.

23. For more details on the discussion within the CPSU Central Committee, the international reaction to T. Kychko’s brochure, and the corresponding Soviet countermeasures, see: Russian State Archive of Contemporary History. F. 5. Op. 55. D. 81. L. 48-70.

24. *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)*. p. 369.

25. For more on this, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 206-211.

26. Ibid., pp. 215-219.

27. For more details on the repressions against the Lviv synagogue, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., p. 220.

28. *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)*. pp. 350-351.

29. *Short Jewish Encyclopedia*. p. 259.

30. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., p. 221.

31. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 216-217.

32. For more details on the campaign against matzah and other Jewish religious dishes, see: *Short Jewish Encyclopedia*, p. 259; *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)*, pp. 355-359.

34. *Short Jewish Encyclopedia*. p. 259.

35. For more details on the scandal related to Yevtushenko’s poem, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 351-370.

36. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 364-365.

37. Topic 19. The Jews of the USSR During the Khrushchev “Thaw” and the “Era of Stagnation” (1953-1985) / V. V. Engel, A Course of Lectures on the History of the Jews of Russia; regarding the Jewish question in the USSR in general and Israel’s activity on this issue, see in more detail: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 176-240.

38. Chapter 5. The Thaw / Yuliy Kosharovsky.

39. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., p. 77.

40. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 272-273.

41. Chapter 6. The Growth of National Activity and the Authorities’ Reaction / Yuliy Kosharovsky.

42. Chapter 5. The Thaw / Yuliy Kosharovsky.

43. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 279-280.

44. For more on this, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 284-296.

45. Iosif Zissels. Jewish Samizdat: 1960s – 1980s / Migdal.

46. Weizmann, Ch. *In Search of a Way*: in 2 books. Tel Aviv: Biblioteka-Aliya, 1990. Book 1. 230 p.; Book 2. 235 p.

47. Chapter VIII. Illegal Zionist Activity in 1960-71 / Margulis, M. D. The “Jewish” Cell of Lubyanka.

48. Iosif Zissels. Jewish Samizdat: 1960s – 1980s / Migdal.

49. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 87-88.

50. Iosif Zissels. Jewish Samizdat: 1960s – 1980s / Migdal.

51. Shterenshis, M. *Jews. History of a Nation*. Herzliya, 2011, p. 503.

52. *Jewish Emigration in the Light of New Documents*. pp. 30-31.

53. Chapter 5. The Thaw / Yuliy Kosharovsky.

54. *Jewish Emigration in the Light of New Documents*. pp. 25-26

55. Ibid., p. 27.

56. *Jewish Emigration in the Light of New Documents*. p. 28.

57. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 321-322.

58. Shterenshis, M. *History of the State of Israel*. Herzliya: ISRADON, 2005, p. 503.

59. *Short Jewish Encyclopedia*. p. 303.

60. *Jewish Emigration in the Light of New Documents*. pp. 25-52.

61. For more on repatriation from the Eastern Bloc countries, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 146-147, 163; Govrin, Y. *Israeli-Soviet Relations 1953-1967*: trans. from Hebrew. Moscow: Progress-Kultura, 1994, pp. 138-148.

62. For more on this, see: Govrin, Y. Op. cit., pp. 160-240; Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 296-322.

63. *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)*. pp. 338-340.

65. Kharkiv / Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia.

66. Chapter 8. The Jews of America Join the Struggle / Yuliy Kosharovsky.

67. For more on the campaign, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 418-437.

68. Ibid., p. 423.

69. Ibid., p. 433.

70. Ibid., p. 434.

71. *Short Jewish Encyclopedia*. p. 261

72. Ibid., p. 262.

73. For more on the Lviv trials, see: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 435-436.

74. Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., p. 435.

75. Kharkiv / Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia.

76. *A Book on Russian Jewry (1917-1967)*. pp. 370-373.

77. *Jewish Emigration in the Light of New Documents*. p. 51.

78. Regarding Tel Aviv’s international activities aimed at organizing pressure on the Kremlin on the Jewish question, see in more detail: Kostyrchenko, G. V. Op. cit., pp. 296-322; Chapter 7. Israel Joins the Struggle / Yuliy Kosharovsky; Chapter 8. The Jews of America Join the Struggle / Yuliy Kosharovsky.

79. Chronology of Events of the Zionist Movement in the Soviet Union / The Exodus of Soviet Jews.

80. *Jewish Emigration in the Light of New Documents*. pp. 44-51.