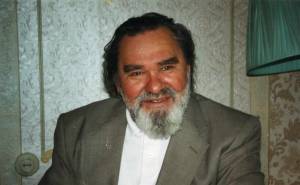

An interview given by Mykola Rudenko, Head of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, just before the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the Group (1 November 1996)

Mykola Rudenko:

This date – the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group – evokes a special feeling. That is the age of adulthood. However, leaving aside sentimentality – what was completely new here was that Ukrainian patriotic members of the intelligentsia for the first time spoke not in an underground mode, but openly, in full voice, defying official ideology, threats, not afraid of imprisonment, retribution. We stated to the whole world: we exist, we know that you will arrest us, but we will still tell the truth. This was a demonstration of courage. However it should be said that by that time the relevant preconditions had emerged.

Two worlds were in collision: the Soviet totalitarian, totally false, lying and armed to the teeth world, and that of western democracy which was developing its tactics as far as the former was concerned.

The Brezhnev leadership needed certainty that the borders which were established after World War II would not be reviewed.

It needed to assert for good the conquests of the Soviet empire. The democratic world understood that they could not allow war to break out, and it didn’t matter where the borders were. They had to demand that the Soviet empire recognize the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights from 10 December 1948 and that it commit itself to establish law-based relations in the country on that basis, i.e. that it would observe fundamental human rights. The Soviet demagogues thought to themselves: how many promises have we made before and never kept, and we always got away with it. We’ll promise again, con the West.

On 1 August 1975 in the capital of Finland, Helsinki, 33 European states, the USA and Canada signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (the Helsinki Accords) which remain in force now. The Soviet leadership had, however, miscalculated: it didn’t expect people to come forward who would tell the truth about the human rights situation in the USSR. The Moscow Helsinki Group was preceded by the Soviet group of Amnesty International which I was a member of. This was crushed. On 18 April 1975 I was detained in Moscow for three days and held in a remand cell.

The idea was to launch criminal proceedings under Article 187-1 “disseminating untrue stories which defame the Soviet State and social order”. However the 30th anniversary of the victory over Germany was approaching, and as a War veteran and invalid I would have come under the amnesty, so the case against me was abandoned. But Andrei Tverdoklebov was convicted over the same case.

Basically the same people who were members of the Moscow Group of Amnesty International in May 1976 formed the Moscow Public Group to Promote the Fulfilment of the Helsinki Accords. The initiator was Yury Orlov a professor and member of the Armenian Academy of Sciences and astronomer. The other members were: Alexander Ginsburg, Anatoly Shcharansky, Petro Grigorenko, Yelena Bonner (wife of Andrei Sakharov), Ludmila Alexeeva, Malva Landa and other human rights defenders.

The name as can be seen was declarative, as if like a shield: we are helping you, and it’s your business whether you accept our help. Petro Grigorenko who was living in Moscow and I thought that we needed to a Ukrainian group and set about this. I tried to persuade him to lead the Group, and he me. It was clear that we were heading into storm winds that could send us hurling into the abyss.

In the second half of October 1976 I had my first conversation on this subject with Oksana Meshko, former political prisoner of the Stalin camps and well-known civic figure. I was introduced to her by P. Grigorenko who passed on letters through her. We turned out to share the same views.

I was on good terms with the science fiction writer Oles Berdnyk, another former political prisoner. And we met up around 9 or 10 in the evening, in the second half of October 1976, I don’t remember the exact date, at Oksana Meshko’s place, at 16 Verboloznya St, in Kurenivtsi. We didn’t talk about that in the house since it was bugged. We went out through a hardly-lit street, up some kind of slope to the tip of some huge canyon. The moon was shining and I saw an unusual landscape. It was a massive clay quarry where clay had been obtained over centuries. (we must one day go to that place). It was like a moonlit landscape. And we were on the edge of a precipice which had its symbolism. Nobody could come up to us from below and in the moonlight we would see if anyone was approaching. We discussed the creation of a Group analogous to the Moscow Group, but it had to be entirely independent. Jumping ahead I would mention that when it was formed, Moscow journalists gave inaccurate information to the West, saying that it was a branch of the Moscow Group, but later corrected this.

We were thus with our Moscow colleagues, but quite independent. Later groups emerged in Lithuania, Georgia, Armenia and Central Europe.

The three of us agreed to approach the two lawyers Levko Lukyanenko and Ivan Kandyba who had been released in January after 16 years of imprisonment and were under administrative surveillance in Chernihiv and in Pustomyty near Lviv. They were not allowed to travel outside their area and they had to be home by 9 in the evening. We therefore had to go to them. We discussed a moral issue: these people had served 15 years each – and we were going to get them involved again? We decided that we would inform them of what we were planning, they were people who were certain, and let them decide.

A day later Berdnyk and I travelled to see Lukyanenko.

We entered his home and saw a true Cossack leader who stands firm. Clearly we weren’t going to talk inside the building. We went to some building foundations on the edge of Chernihiv where there was a large open area – we knew that the KGB had equipment that could pick up conversations over half a kilometre. Levko liked our idea. He already knew about the existence of the Moscow Helsinki Group from Radio Svoboda even though they tried to jam it. He was, he said, in full political and civic form. We told him that we would understand any decision. Levko replied: “You know what, leave me to think about it for half an hour”. Berdnyk and I walked on ahead, he remained around 30-40 metres behind. Exactly half an hour later he came up to his, took us by the hand and say “OK”. His smile was sad since he knew better than us what kind of fate was awaiting us. “Fine. I’m joining. Consider me a member of the Group. So Lukyanenko was the fourth.

Then I went to Lviv and found Mykhailo Horyn. He was going through a difficult period. He said that at that time he wasn’t prepared to become a member of the Group but that he would support it (and after our arrest he took upon himself a huge part of the work). We knew his position, and we were intending to ask Ivan Kandyba.

In Pustomyty neighbours showed us the booth at a market where Ivan Kandyba repaired irons. That was how the lawyer earned a living. He treated me with some suspicion., but was polite with me. We went to his home. I took a bottle of horilka [vodka] but Ivan didn’t even touch it. I dozed a little because I was very tired. Poverty in the hut, and you couldn’t talk … Later we went by train to some kind of forest, to a clearing. I could feel that something was holding him back. He said no.

Nina Strokatova, wife of political prisoner Svyatoslav Karavansky who had herself just served out a four-year sentence and was now living in Tarusya in the Kaluga region passed on via Ginsburg that she also agreed because she couldn’t stand on the sideline.

There were no foreign journalists in Kyiv so I had to go to Moscow where on 9 November I announced the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. I stayed the night with the Grigorenkos. And in the morning Ludmila Alexeeva phoned to say that my wife Raisa had reported that our flat in Koncha-Zaspa near Kyiv had been devastated. As soon as the broadcast from Radio Svoboda was made, between about 11 and 12 in the evening, a military horde surged out of the forest. There may have been a lot of them, since in one moment, or in a matter of seconds they showered bricks on our flat on the second floor. Since there was netting against mosquitoes on the windows, not so much actually got into the flat. But you could have picked up half a wagonload of them. Oksana Yakivna Meshko was staying in the flat, together with my wife Raisa. They were already in bed so immediately covered themselves with blankets and pillows. Oksana Yakivna was hit on the shoulder. That was the “salute” from the Committee for State Security’ [the KGB] to mark the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

Obviously I immediately added that information to be broadcasted to the world. Ivan Kandyba heard about the formation of the Group, realized that I wasn’t a KGB agent and phoned me in Kyiv. He apologized, saying “I thought somebody else had turned up pretending to be you”, and he joined the Group.

Two other young men came as well – Myroslav Marynovych and Mykola Matusevych. Marynovych was such a rosy-cheeked and blossoming young man, who looked very young. Matusevych was the Cossack type, honest, direct, a bit impulsive, but firm, and it was clear that he wouldn’t let betray you, that he’d withstand the test. And indeed that’s how it was. I remember Marynovych’s words: “We want to be witnesses of the fall of the empire and take part in those events”. That was already nine people.

We were brought a lot of information. We drew up a list of political prisoners, around 100 people who were in the labour camps, prisons, psychiatric hospitals or in exile. I wrote Memorandum No. 1.

We defined the treatment of Ukraine as genocide. That needed some daring. I also wrote the Declaration of Principles. Armed with those drafts, I visited Lukyanenko. A man dropped in, cultured, upright-looking and neatly dressed. Levko introduced us. His name was Oleksa Tykhy. They were on informal “ty” terms [Ukrainian has two forms for “you” – translator], like brothers, they shared a labour camp past. Levko had given Oleksa our documents, saying read them and join us if you like. Oleksa added that there’d been a search made of his place, and a colonel had hit him. The KGB were very bothered when their names appeared in such documents. Oleksa Tykhy became the tenth founding member of the Group. Later I met him in December in Alchevsk in the Luhansk region, at my sister’s place. We spent about a day together, and I understood the stature of the man. We were both arrested on 5 February 1977, and then met in the defendants’ seats.

That was a strong surge of the national spirit. On 5 February 1977 they arrested Oleksa Tykhy and myself, and then almost all the first ten, only Petro Grigorenko was thrown out of the country, and they didn’t sent Nina Strokata to the camps again. However after us, one after another new people joined the Group, although they could see that a person who declared his or her membership of the Group did not remain at liberty for long.

The members of the Group were not the whole Group. There was a circle, a second level which collected information, transported it, typed it out, like my wife Raisa, the informal secretary of the Group – she served 5 years and exile for that.

I should mention that the Ukrainian Helsinki Group did not fall apart or dissolve itslef. The Moscow Group – some were arrested, some “thrown out” of the country, some fell silent, and in 1982 it folded. Ours however, for all that it was totally paralyzed by arrests (Ukrainians were not thrown out of the country), nonetheless held out.

… In the camps there were people who were there for having formed underground groups, for distributing two or three dozen leaflets, for samizdat. They got the same sentences as us but nobody knew about them. I value highly their heroism, but new times demanded new methods. We decided on principle not to engage in underground activities. We would go with open shields, place our signatures and addresses on documents, i.e. here we are, we are telling the truth, and you do what you want with us.

The regime was thrown off balance, they didn’t know what to do with us. Do you know that I was arrested on the decision of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU? We found out after the CPSU was disbanded. They found documents: the Prosecutor General of the USSR Rudenko and the Head of the KGB Andropov applied for permission to arrest me, Ginsburg, Orlov and the head of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group Ventslovy. The Politburo approved this. The proposal read that Rudenko had to be tried by the Donetsk Regional Court, and for that “there are procedural grounds”. That meant I had to be tried together with Oleksa Tykhy who lived in the Donetsk region. And Tykhy only signed the documents, he didn’t have time to do any more. Well, with him it was easier for the authorities, he was a former political prisoner, whereas I was a War veteran and invalid.

The Russian President Boris Yeltsin once said that the Moscow Helsinki Group had played a huge role in the moral renewal of Russia. In Ukraine the role of the Helsinki movement is still hushed up.

The interview was taken by Vasyl Ovsiyenko, who was himself later a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group