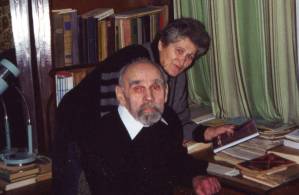

Interview given by Anna Hryhorivna Masyutko. Recorded in Dnipryany, Kherson oblast’ on 10.02.2001 in the presence of Mykhaylo Masyutko who was not capable of telling the story himself.

V.Ovsienko: It is February 10, 2001 [we are] in Dnipryany near Nova Kakhovka, in the house of Mykhaylo and Anna Masyutko. Is your name Anna Romanyshyn?

Anna Masyutko: Anna Hryhorivna Romanyshyna – it is my maiden name. My married name is Masyutko.

V.O.: Mykhaylo Masyutko’s spouse. We are in Naddnipryanska street, 87. What raion is this?

А.M.: Dnipryany fall under Nova Kakhovka jurisdiction.

V.O.: And what is your mail code?

А.М.: I have it written down here– 74987.

I, Anna Hryhorivna Masyutko., was born in 1925 in Kutkir village, close to Krasne village.

V.O And where is that Krasne?

А.М.:Near Lviv, Kutkir village, Lviv oblast’. My parents were peasants. Father worked as village council secretary. Mother took car of our household. My father’s name is Hryhoriy Romanyshyn, my mother’s name is Teklya Romanyshyn. They worked and lived together in Kutkir. In 1950 father and mother were deported to Siberia. We were left behind because we studied and lived in Lviv at the time. They did not find us, so they took only father and mother. But they kept looking for us. In 1945 my sister Maria Romanyshyn was arrested. She just turned 16. She was brought to Krasne village and interrogated there – whom she worked with, what did she do etc. But she could not confess, would not confess. Investigator Romanov was interrogating her and when he ordered her to recite “the ten commandments” she started reciting the ten commandments from the Bible. He shouted at her:” I mean not God’s commandments, but ”banderivtsy” commandments!” A man rose from the corner, and hit her in the face with his open hand, wide as a dolly. Then he continued beating her with a leg of a chair. He beat her with this stick. She would not give out a sound, did not even cry. She told me later that while he was beating her she was imagining Jesus Christ tortures and thinking that Jesus must have suffered worse than she. And she did not cry.

Then the investigator gave an order: “Hang her!” The man who had beaten her took her out into the corridor. In the corridor she saw three banderivtsy boys on the floor. They were wounded, covered in blood, but still alive, when she was passing them. She just took a look, but was not allowed to stop. She was taken into the courtyard. There she saw another banderovets, half naked, lying on the ground. She saw a cross on his chest and a soldier urinating just on it. That boy was not alive any longer. She was taken to some basement – there she saw a rope to hang her and a stool. He shouted “Get upon the stool!” She obeyed, and then waited. He put a rope around her neck and shouted: “Confess now! Did you work, did you work for banderivtsy? What information did you bring them?” She kept silent and never uttered a word. And he kept shouting and calling her obscene names, then kicked the stool and she hung from the rope. He cut the rope immediately. She fell and he poured some water on her face. When she got up, she was taken back to the same room. Again he was asking questions, but she never said a word. He said:”Take her to the cell!” And she was put into the cell. The same happened to every girl who had been caught. They were six altogether.

After that she got sick, very sick. In jail she developed pneumonia. The other girls managed to write a note on a thin piece of paper asking for a lot of butter because Marusia had pneumonia. They rolled it, put it inside small piece of bread and placed it into a trough. When mother brought them a parcel they would give away the empty jars and receive the full ones. I forgot to mention that mom was back by then – they were held in Zolochiv prison. When mom brought the jars home, grandma started washing them, the bread got wet and the note fell out. Grandma called mother “Come here, look what it is!” Mother took the note and read it. On learning that Marusia was sick they began crying and lamenting. Mom started bringing them food so that the girls could feed her, because they also mentioned that she could not get up on her own, they had to support her.

After sometime it became known that the girls were to be deported to Siberia, because Zolochiv prison was overcrowded with prisoners. And a foreign delegation was to come, and the jail was full. So they did not stand trial, but were just deported to Siberia without any verdict.

They were brought to Vorkuta. Marusia was still sick. They were assigned hard jobs. They were building the railroad. They received quilted jackets and felt boots, because it was a winter time. The pockets of the jackets were full of all sorts of metal parts, big wedges to be drawn into the rails. They were needed for construction, but not brought to the work site proper way the girls were made to carry them. She was still sick. Girls had to carry her from work, she could not walk. Then she was put to a hospital.

She was very weak by the time she was taken to the hospital, stayed in bed and could not talk, could only hear. At night an inspection came to look at the patients. They approached her bed and said: “This one can be taken away already. Bring the stretcher and at night take her to the mortuary”. She told me she heard all that but could not say anything. But God’s miracle happened – the Lord sent that man. He worked there as medical aid, a convict also, from Leningrad. While she lay there sick he used to read our letters, letters from home to her. He heard the order to take her out alongside with other corpses, but he did not obey. Instead he gave her some shots, injections of some vitamins. He was a nurse, and his father, a doctor from Leningrad, was sending him various medicines. He gave her injections and some food at his discretion. He was trying to save her.

When they came back some days later they saw her alive and asked him: “So she did not die after all?” “No” – he answered. “But what did you do?” –“I gave her shots, such and such.” – “OK, let her be then”. And so she stayed there. A Lithuanian doctor, also a convict, was a chief physician of that hospital. He also helped and eventually she started returning to health. When she could walk and talk the doctor started giving her work in the clinic. She helped him in bandaging wounds. She learned a lot of medical stuff from this doctor.

When she was already somewhat better she was ordered to take care of a guest-house where the visiting bosses stayed. She had to do the cleaning and to wash the floor every day. They were fed there and they could rest there. Once a big boss Ovpil[unclear] came, he was a very important man there. The house was warm, she got everything ready. He was eating and she stayed behind the stove, knitting socks or something else, I don’t remember.

He finished his meal, came closer to her, took her by the chin and asked: “Do you want back to you mom?” “I do, but I was brought here not to have my wishes fulfilled” – she answered. No. I can make it happen that you will be taken home”. He took her in his arms and carried her to the couch, which was there for his rest. While he was carrying her she understood everything and started struggling with all her might. Finally she became so weak she could not oppose him any longer, but he stopped insisting too. When he calmed down thinking she was an easy prey by now she managed, with one last effort, to kick him so hard that he fell upon the floor. She jumped out of the house and ran to the clinic where she had worked with the doctor. The frost was severe, very severe she had a long way to run and no coat.

When she arrived he was completely amazed: “What have you done?” He understood immediately, though, that it was about that Ivan Ivanovych, that big shot. “What have you done?” Later that Ivan Ivanovych gave an order for her to be sent to the common works to toil till she kicks the bucket”.

So she returned to the hard job. She went to a wareroom and was given clothes from someone sick. That person had diarrhea, and the pants were so dirty she was disgusted to wear them. But they gave her nothing else. The jacket, the sweatshirt and these pants. So she smartly turned them inside out, found some cord for a belt and joined the other girls to be taken to work. The girls started laughing seeing her, because she looked like a living horror. The officer in charge looked at her and ordered her to step up. She obeyed. “What is that?” “This is the clothes I was issued”. He shouted at her and sent her back to that wareroom with the order to get another set. That is how she managed to get another pair of pants.

So she worked and worked and got sick again. She barely survived. But the doctor kept helping her. He was Lithuanian, an elderly man. She kept saying he reminded her of our father.

But the end of her torment came. Eventually she received a decision on her release. Why so? Because she had not been tried or convicted.

The girl who had belonged to the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists was arrested. She was tortured terribly. They put her hands on a hot stove and kept them there till she gives out the names of other girls who worked with her. Then they put needles under her nails and she started giving out names. All the names were put down and all the girls were detained and deported, like I told you before. And during the trial at which she received 25 years, she was asked if she wanted to have a last word. And she replied:”There is only one thing I want to tell you. All the names of all the girls I’ve given to you are false. I never worked with them. I just babbled whatever came to my mind”. “Why did you do that?” – “That is why –and she showed her burnt hands – they tortured me and I talked with no grounds at all”.

When my parents were deported in 1950, we have been looked for. We were in hiding. My sister had to marry she got married and went to Lutsk. I was hiding at my friends’ places, spent each night in another house. I believed it might help me in my hiding. But it did not work out that way. After two months I came to my place, to the flat where I had lived. I came home believing they won’t come for me. But I was wrong. One night the doorbell rang they came and took me away.

They placed me in the transit prison. I spent 9 months there until they found my sister. Once she had been found and brought to Lviv transit prison we were ready for the transport. We were together by then. “Black Maria”s took us to the train station. On the train we met a young girl from the Carpathian Mountains. She was rather sick and held to her heart all the time. She would bring out a tiny bag, like 3 cm wide and 5 cm long. She managed to stash some sugar in this bag and would take it out and lick the sugar. We had something, so we tried to fortify her with more sugar and food. We asked her and she told us that she had been tortured severely in Lonsky prison. And presently she did not know where she was being taken. Such a meeting we had on the train.

The train brought us to Kiev, where we’ve been put to a cell. There was a lot of interesting details, but it is kind of secondary to my story.

We spent three days in the cell and then we were called out with all our belongings. My sister’s name was called but not mine. Anyway I stepped out with the rest of the girls. We came out the guard counted us and saw someone was redundant. He asked who it was and I said it was me. “Why did you step out?” – Because I am coming with my sister, we are being taken to our parents”. We held on to each other firmly and no matter how hard the guard tried he could not separate us. I began crying, while he took the girls downstairs, and we followed them. We stood by the wall and cried, when an old colonel with gray hair came to us. He approached us and asked: “Why are you crying, girls?” I explained that we were being separated. He reassured us, went away and returned with my file. He took some other files away, but my file remained. It meant we were together.

After Kiev we were brought to Kharkiv. I want to tell you that in Kharkiv we had the worst conditions [unclear], the worst guards, and the worst escort. On our arrival we were herded to “black Marias”, and I fell more than once on the way. The guard would catch up with me and kick our things, our bags with his foot.

We were brought to Kharkiv jail, a regular one, not the transit one. All the cells were full. So they put us right on the floor – the Hutsul girl who had been with us on a train from Lviv for the whole trip, my sister and me. They ordered us to stop in the courtyard. We stood there and saw a whole family – an older woman-mother-, a daughter, about 25 and son, about 26, maybe, stepping out of “black Maria”. We were taken upstairs and told to wait there.

They said:”You are spending the night here. All the cells are full, so you are spending the night here”. The mother with the daughter stayed with us and the son was taken to the men’s cell. It was in the morning. We stayed there till evening and then for the whole night. Next morning we saw men being taken to the toilet. It was not far from we were, on the opposite side, a bit further. The latrine was horrible. No sewage, just water and bricks on the floor, and these bricks are all covered not in water, but in urine, and people had to step over it. So the men were taken there and locked. And that guy was with them, too. Once his mother saw him she started quickly putting some food together to give him. But as they stepped out of that latrine, he was not among other men. Finally we saw him between two guys supporting him on both sides while he was barely moving his feet. His mom came to him, to give him something to eat, but the guards pushed her aside and took the men to the cell.

I’d like to mention that the corridor was divided in two by the glass doors, like a kind of glass wall. And we saw the men taken to the last cell, the boy too. We were trying to comfort his mother as best as we could.

We spent another night there. In the morning we saw these guards opening the cell – and suddenly that boy ran out and started circling around, very rapidly, quicker and quicker. One guard went away and returned with a fat “moscal” [derogatory for Russian – Ukr.], who kicked this boy below his belly, so that the boy bent in two and could not straighten up. They took him away.

Oh, how scary it was! We did not allow his mother to look. But the sister saw everything and kept silent. So he was escorted away bent like that. He never straightened up. Later a cleaning woman came to wash the floor in that corridor. My sister approached and asked her about the boy. And the woman answered: ‘He hung himself”. That was the end of it. Whether he hung himself or not…I think he could not hang himself, he had nothing. It was them who hung him. I wanted to relate this episode to you. One should have seen it. It was horrendous. [Recorder is switched off.]

In 1965 my husband, Mykhaylo Masyutko, was arrested [in Feodosia]. They came to the house, six big, stolid men and immediately started the search. They showed a search warrant and started the search. They took every book from the shelf and looked through it. All the books lay in a heap on the floor. They were fumbling through all the papers, no exception. And a page fell out. It was in my handwriting, I have copied a poem. I do not remember the poetess’ name, but the poem went as follows: “You won’t perish, our dear Ukraine, but rise in glory and in fame again the streams of blood which soaked your earth will resurrect your heroes, love and truth!” The page fell out and I took it when the officer did not look. I took it and put it my pocket. But he managed to read the verses. In a few minutes he turned around and asked: “Where is the paper which was here?” “I don’t know – said I –you are frisking the books, so look for it”. –“No, it was right on top”. “Keep looking…” he never found it because I hid it.

They were writing [the titles] of books, which they put aside, into the protocol. They threw some books on the heap. My husband had a lot of precious books on history. They took whatever they liked and put in their bag. They also collected his files, all his writings and took them away.

Then Daria Oleksandrivna, my mother-in-law, and I went to KGB, where he was taken by a car. We were called and asked whether we had known about his activities, about the contents of his writings against soviet power and things like that. They let us go and so we left, but first asked where they planned to take him. They told us he was being taken to Sebastopol.

He was to be taken to Sebastopol. But we went to the prison where he was kept and stood on the opposite side of the street. After long waiting the doors opened and he was taken out. He looked downwards and did not see us. But we saw him. They pushed him into the car quickly and took him away. And then we began crying and as long as I stayed there I kept crying, because on top of everything he was sick at the time. He had stomach ulcer. I was very upset.

Eventually we were informed that he had been taken by plane to Lonsky prison in Lviv. I started bringing him parcels. All those days I spent in Lviv. I left behind elderly mother who suffered terribly. I brought parcels. They won’t accept them. Very rarely they would accept. I came to investigator Volodin and asked to take a parcel. He said:”No”. – “Why not? He is sick, he needs that parcel.” – “He behaves like no one else. We will not accept the parcel”. And they didn’t. Almost every day I was there, pleading and waiting. Finally, one day I came to the window where they accepted parcels and called. A head popped out and said “Go to Berlov street”. I did not understand and asked again. “I told you, Berlov street”. He meant Brullov street. I understood, then. A woman behind me said “It is Brullov street, behind the jail”. I went there and passed everything to him, but I don’t know whether he received anything or not. So I kept bringing these parcels till the time of the trial. I stayed at home, embroidering a napkin, which I called “Tears”, I’ll show it to you. Finally they announced the trial date. It was that investigator Volodin who told me that trial would take place on such and such date.

And there was a trial. He was questioned, but stuck firmly to his beliefs and tried to convince the judge with quotes from Lenin’s works. The prosecutor Sadovsky was a bad prosecutor. He cut him in the middle of the word, interrupted him. But Masyutko managed to say what he knew and wanted to say.

He was tried and condemned to seven years with confiscation of his house in Feodosia. He submitted cassation appeal. In fact, they failed to prove his guilt, so the cassation court reduced his term by one year and repealed the confiscation. The philological evaluation to prove his authorship cost money. Nothing doing, we had to pay that. How much we paid? Seven hundred something rubles, as far as I remember, right.

So it goes. After trial he was taken to Mordovia. And then my tortuous trips to Mordovia for visits started. Visits were irregular – sometimes they were allowed and sometimes not. Once, I remember, I went to Mordovia bringing warm clothes, underwear and kersey boots. I brought it all, then waited for three days for the visit permit. We met, spent some time together. But when I wanted to leave these clothes with him, the officer said “No”. I was literally kneeling in front of him pleading him to accept “Please take it. He has no appropriate clothes. He is cold”. – “No!”

I was nearly killed by such inhuman cruelty. I had to take everything back. He took the food products, but no clothes. As I started from Feodosia, where it was warm, and ended up in this cold climate, I had to wear all these warm clothes myself even my sandals were replaced with kersey boots. I was walking through the forest from that Mordovia to the train, and suddenly I felt wetness in one boot. I wondered why. I took the boot off, although I did not have much time, and saw blood. The boot rubbed my foot so sore that it even bled. I bandaged my feet and hurried to the train to Pot’ma. In Pot’ma I waited for Saratov train. I boarded it when it arrived but there were no free seats. The woman conductor told me to go the end of train and find a seat. I did as told and saw some men playing cards.

I took a seat, but both lower and upper berths were all occupied. Finally they started making beds, and I was sitting humbly. The woman conductor came and scolded them “How can you? Shame on you! A woman barely has room to sit, and you made yourself comfortable! Give her some room, at least to lean to the wall!” After she scolded them, one of the men moved a bit and so I reached Moscow.

Everything was dreary in Moscow too. At the railway station I saw a “kulak” sitting on the floor: he spread a newspaper in front of him on which he had bread, an unfinished bottle of vodka and small smoked fish on it. I was sort of surprised: people were passing right by him, and he was just nipping off his bread sitting there.

From Moscow I made it home to Feodosia. Such were my tribulations for the sake of my husband. Now it is hard for me, too, because my husband is sick. He lost his memory. He had phenomenal memory – he remembered everything. But now he does not remember a thing. That is our life now.

V.O.: Did you write letters? Your letters were confiscated, right?

А.М.: The letters were confiscated. We corresponded – I would write him and he would write back to me, but he was allowed only one letter per month. He had tough time there, performing very hard job, loading some parts of machines, some metal stuff. They were so heavy, his stomach ached.

When he returned from prison, they refused to register him, although his release form said he could return to his home in Feodosia. Every day militiamen came trying to evict him. But we tried our best we went to Kiev, although we achieved nothing there. KGB boss told us that if he allowed registration he would be detained himself the next day and taken to places from which Masyutko had just returned. So we returned with no results. Then we decided to sell the house. But we were not allowed to sell the house to the people from the outside who had offered us thirty thousand. “Sell to the locals only”.

We decided to seek an asylum somewhere else. He recollected that here, not far from Nova Kakhovka, in Dnipryany, lived his grandfather Masyutko and he used to come there as little boy. KGB gave permit for registration there. We got registered and went to visit his aunt. His uncle was killed leaving his wife behind. So we visited that aunt. First she stayed with her sister. The squalor was unfathomable. She was an elderly lonely woman. She received a pension of ten rubles a year and was almost a beggar. But she helped us in finding an apartment, and that is where we lived, not far from her. We lived in that apartment till 1977. My old mother in Feodosia rented our house and sent this meager money to us.

But there was no peace for us. He was a retiree already, but I still had to work. They summoned me to the village council:”What are the sources of your income?” – “What do you mean? We had some savings.” –“What savings? What kind of savings can you have? Aren’t you ashamed to go to a store, and buy bread while people have to earn this bread and you just go and buy it?” “But I buy it for money, I am not given it for free” – I retorted. That was our conversation. And when my husband entered the room he shouted: “And what do you want? Away with you!” And his tone of voice…It was terrible.

We had to go through all that. Quickly I found a job. There were no jobs, but I remembered I had studied at the applied art school in Lviv, class of textile. I specialized in textiles. I was taken out of the institute. I just entered the institute, but was arrested right away. I am textile design specialist, but there was no work for me anywhere. And we were given a deadline – if I don’t find a job within one week, I’ll have to go to court. We looked through all the job announcements. Finally we found one – that of a janitor. i.e. to work as a caretaker. We went there. It turned out to be a kindergarten. The manager agreed to hire me. But when I came the next day she said: “ No, you know, the position is filled already, a young girl got the job”. Three days later we were passing the kindergarten and my husband told me: “Go and check how she is copying with the job maybe they have another cleaning position.” The manager said:”Oh, I am glad you came. The girl does not want to work because she does not want to take a medical test.” And so I started working there with my husband helping me. It was in autumn and leaves kept falling and falling. We swept them, then my husband buried them and that was our “janitoring”.

Meanwhile we were looking for another job. And we found it – making wreaths in a funeral home. I did not know much about wreath-making. But then the director came and asked me if I could write a line on a ribbon, and I could. She brought the mourning band and I wrote the line in question. She was fascinated: “Oh, how wonderful! You will be writing inscriptions on the bands”. –“All right, I will.” So due to this band I was hired as an artist for the communal services agency. I didn’t know the fonts, but as my husband had studied in the polygraphy institute he taught me all that stuff and I learned quickly. With his help I painted all sorts of boards and slogans.

And thus we lived till 1977, under surveillance all the time. I mean, my husband, not me. The KGB officer used to come regularly to talk. He was smart man and in course of conversation he would say:” Mykhayko Savych, please don’t misjudge me I wish you nothing wrong, I just want to talk to you as you are a clever man”. And why did I call him smart? Because once he brought an officer from Kherson KGB and this latter also tried to persuade my husband to work together. “You will be writing”, like. Well, my husband responded so unambiguously, that they did not try any more. At the end of the conversation they asked: “So, how are your lemons doing?” My husband kept a hothouse where he had planted oranges and lemons. My husband answered: “Not bad - they are growing. Recently they blossomed.” And the officer asked the permission to have a look at them. “Why not? Sure you can”. – “So let us go and take a look!” I was following them both – the officer from Nova Kakhovka and the one from Kherson. My husband was showing the way. And our KGB boss, Borsuk by name, asked “May I speak Russian?” (in general he spoke Ukrainian). And Masyutko replied: “Speak whatever you will, Ukraine is not free yet.” And the guy from Kherson turned abruptly and said: “And will never be”. They took a look at the lemons, sat on veranda and then went away.

So we were under surveillance till the very independence of Ukraine. But the KGB man did bother us a lot. He used to come along, ask something, tell us some news and be on his way. Because his dacha was not far away. He even brought us water-melons, so well-disposed he was.

In 1977 mother moved in with us in Dnipryany, and we started looking for a house. We found one. We sold our property in Feodosia for twelve thousand and bought a miserable hut in Dnipryany for the same twelve thousand. It is where we are living right now.

In 1984 mother died. She was a seer and before her death she said: “Mykhayle, it will be all right” “What will be all right, mother?” – asked Mykhaylo. “It will be all right for all of us”, she answered. These were her words. Now we know what she meant, probably she sensed something. Anyway, these were her words.

V.О.: And how did Mykhaylo work upon his book? Since when?

А.М.: He was working on his book while we were still in the rented flat. Our room was pretty spacious. I divided it in two with the curtain and he worked behind it. There was a small couch on his side, a little table, so he was writing, bit by bit, but with great caution, because the other half of the house was occupied by the party members. Their daughter married a militiaman and the whole family lived in the other half. More than once her husband would open the door without knocking and ask:”Mykhaylo Savych, what are you doing?” Well, by then Mykhaylo Savych was ready, he would come out and ask the man what he wanted. Thus, clandestinely, he was writing.

V.О.: Did he write or type it on a typewriter?

А.М.:It was handwritten, all the way. Later when we had our own home he would type or have someone type it for him. And all the time he was covering and hiding it. It was well-hidden, and he managed to finish it. By that time his brother dealt in publishing business. The brother, Vadym.

Mykhaylo Masyutko: That was the way a writer had to work in the Soviet.

V.О.: First you earn a good story in prison and then you put it down.

А.М.: Well, what else can you say? Now, when my husband can do nothing, because he is sick, all the home chores are on my shoulders. I even have to cut the wood for the stove. It is very hard on me, but nothing can be done about it. My sister who lives in Lutsk is asking us to join her there. The house is difficult to sell, but we are trying. We hope to sell it and move to Lutsk, to my sister, to spend our late years, because she is lonely, too.

V.О.: Do you know the address?

А.М.:She lives in Lutsk, Romanyuk st. 1, apt. 5.

V.О.: And what is her name?

А.М.:Maria Novosad, my sister.

I told you earlier how my sister and I were deported to Irkutsk oblast’ to join our parents there. Our parents lived there. They were assigned a tiny hut. We cleaned it up and lived there. My sister’s husband came to join her in Irkutsk oblast’. The settlement was called Kukulyonovka. But her husband had an advantage of finding a better job, because he had come as a free man. He found a job in a store. They had a small store there. So he worked there as a shop assistant. They had a spare room in the store, and that is where they lived.

But my mom would not go to work on principle. She did not work there even a single day. And somehow no one made her work. She was an older woman. But my father and I worked in menial jobs. I weeded potatoes and grain fields, rammed soil with the special machine I carried bags, till I’ve developed radiculitis. But prior to it we worked, and father worked very well.

My father and mother used to sing in a church choir. So when anyone died they were invited to recite the prayer. They knew all the rituals and they sang, and so people respected them - to such extent that when he would come to the office to get the job order for the day, the scum, the jail-birds sitting there did not dare to use profanities in his presence, although they could not say a word without obscenities. That is how it was. Father was respected. He never declined any work. Whatever the brigade-leader would order him to do, he did it. Both the brigade leader and the kolkhoz head used to say in the club: “Had everyone worked like old Romanyshyn and his daughter Anna the kolkhoz would be doing much better”.

And thus we worked till Stalin’s death. When he died in 1953 my father immediately wrote a petition to Moscow, asking for release of his children, i.e. us. Malenkov ruled at that time and very soon we were released. The arrangements were made for us to go to Lviv from Siberia. My sister had place to return, so she went to Lutsk together with her husband, to her father-in-law. And I went to my colleague in Lviv.

Two years later, in 1956 father and mother returned. In Kutkir village people respected father also. Father asked [the authorities] to give him his house back. But another man was living there, by name of Dykyi. He did not want to free the place. He started taking off the roof which was made out of white zinc. He was building a hut and wanted zinc for the roof. Mother went to talk to him and ask him to give the house back, but he said he could only sell it to them. “So, man, how much do you want for it?” – mother asked. “I want two and a half thousand”. –“This is too much, where can we get such money?” And he said: “It is not too much. A single sheet of tin cost so much”. Then mom retorted: “Did you buy these sheets? You received the house free, and it is all ruined”. Anyway, mother did not come to see him again. But he was trying to sell the house. People would arrive and go to him to bargain. But the local people, aware of what was going on, would warn potential buyers: “Don’t go there, guys. This house is unlucky. People came from Siberia and want their house back and he would not sell it to them. The buyers would turn their horses and ride away. But then a man came, negotiated with him and they were preparing contract already. He learnt the price, and, I believe, they agreed on one thousand eight hundred.

When this man came out into the street, the locals met him and said: “What are you doing? You are buying the house of the unhappy people who got back from Siberia”. “I did not know” – he answered. Turned out these people were members of a religious sect and they wanted to talk to mom and dad. The man said: “I will sell the house back to you, because I have almost bought it”. So my parents had no choice. And people in the village somehow managed to collect some money. We also sold some things. Marusya and her husband Yurko borrowed more money in Lutsk and finally we bought the house back. The hut was all ruined, everything broken, windows broken, no stable, no shed. Father started putting things in order, but fell ill. My sister and her husband came and took my father and mother to Lutsk.

In Lutsk she took care of them. Father stayed in bed, could not get up, so she raised him to treat bedsores.

In 1977 father died. Then her husband became seriously sick. He was war veteran and disabled. He developed wet pleurisy, and in the year seventy [sic – B.V.] he died. After the funeral they remained just two of them – mother and she. She worked in a store, as an assistant, as a cashier, and at many other jobs, but at least she stayed at one place. It was just mother and she.

A year after her husband died a friend of his proposed to her. She married him. He was a dentist. Her life improved after that, because it was hard to fare on her own. He had a weak heart. Soon after mother’s death (in 1982), he died too. And she took care of them all, helped them all and had four people die on her hands. And now she is asking us to come and live our last years together. That is it.

V.О.: Thank you.

[The end of recording. Mykhaylo Masyutko died in Lutsk on November 18, 2001 and his wife Anna – on May 24, 2006. They are buried in suburban cemetery “Harazdzha” - V.O. ]