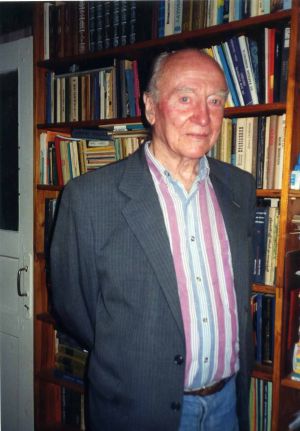

V.V.Ovsiyenko: June 4, 2001, on the second day of the Holy Trinity, in Korostyshiv, Zhytomyr Oblast, in apt. 17, still 112, Bolshevik Street, we converse with Mr. Metodyi Volynets. Vasyl Ovsiyenko is recording.

M.I.Volynets: I, Volynets Metodyi Ivanovych, was born on March 3, 1926 in the Village of Ivanivka, now Travneve, Korostyshiv Region, Zhytomyr Oblast. My father Ivan Mykhaylovych Volynets was a collective farmer until his death and my mother Yevdokiya Danylivna Volynets, maiden name Potapenko, also a collective farmer all her life. My father was born in 1889 and died in 1984. My mother was born in 1891 and died in 1976. My elder brother Kostiantyn was a teacher in his native village, he died ten years ago. My younger brother Hryhoriy graduated from an institute, he worked as an engineer and furniture maker at the furniture factory in Ichnia, Chernihiv Oblast. He died three years ago.

I went to the grade school in my Village of Ivanivka and then finished a seven-year school in the nearby Village of Berezivka (now Sadove). Before the war, one year I attended Ivan Franko Teaching School in Korostyshiv and passed exams for the first course right after the outbreak of war in 1941.

During the war, I lived on the occupied territory in my village. Then my teacher at the Teaching School got me involved in the anti-fascist underground. It was the first local guerrilla group of Volkov-Kucherenko, which later joined the formation of General Naumov. I fulfilled various tasks and traveled about the oblast.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What tasks did you carry out?

M.I.Volynets: We prevented the transportation of people to work in Germany, put vehicles out of action, threshers, and tractors in order to prevent the export of grain to Germany. In wartime we fired at German machines, put out of action military communication cable Kyiv-Zhytomyr, which the Germans laid on our territory. This was our job down to the end of the war.

For the first time the Soviet army returned to us on November 9, 1943. On November 19, they again surrendered Zhytomyr to Germans, and returned to us on 27 December.

From January to March 1944, I worked as a secretary of the Soviet of the village council and collective farm accountant.

On April 3, 1944, I was called up for military service and taken to the training regiment in Kazan. In Kazan, we stayed for three months and then were transported to a training regiment located near the Inza Station, Ulyanovsk Oblast, and then, at the end of August 1944 we were transported to the front. In early September, we arrived in Lviv. In Lviv, we suddenly unloaded and received an order, “For some time we will be stationed here. The 39th reserve infantry regiment of the 43rd Infantry Division from Siberia arrived In Lviv and we reinforced this regiment. Here we served.

From the beginning, we were sent to perform forest-harvesting operations near Bibrka (where the underground headquarters of General Shukhevych was located at the time). There we fell the age-long beeches for firewood. Then my group was sent to carry out haymaking and build up a stock of oats for the horses of our artillery unit, I served in artillery. Our group of six men went about the villages of Bibrka area (I still remember their names: Velyki Hlibovycha, Volove, Pidhorodyshche, Romaniv, Pidyarkiv, Horodyslavychi, Sholomyya) and collected from the villagers against state deliveries forage for our horses. Here the war was over for us, we did not go any further.

After the war ended in Europe the command intended to send us to the Far East. But before they managed to form a marching column, everything was settled without us and Japan surrendered. We stayed in Lviv. Then our regiment was sent to Bibrka area to protect the road against the so-called Banderivetses. And along the highway they drove cows and horses from Germany.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Why did they do it?

M.I.Volynets: Cows and horses were driven here from Germany, to the Soviet , as reparations. It was intended to restore the head of cattle, which the Germans ate and took away during the occupation. Therefore, I knew these villages very well, saw how people lived there, how they were bullied. It was obvious. I had many acquaintances there, and they are still alive. We, young guys, met local girls and corresponded with for a long time after.

Free Ukrainian Youth Association

(March 1945--April 1950)

It happened sometime in late February or early March 1945. There were three of us: Myroniuk Vasyl, he was a native of Ternopil Oblast, Kremenets Region, Mykhailo Chekeres, he sang very well, a native of Kirovohrad Oblast, and I we came to Lviv to take food for our unit. On the way back we walked down Zelena Street to the outskirts and hitched a ride. We were armed with submachine guns. At the time there were only military vehicles, there was no civilian transport. Any vehicle would give us a lift, especially security officers, for fear of attack, while we granted a sort of protection. We waved down a vehicle. In the car, there were three soldiers and a driver, a MIA lieutenant was sitting next to the driver. We had to go straight past the Village of Davydiv, but short of Davydiv Lieutenant commanded suddenly to turn left and down the dirt road we raced towards Novomyliatyn, here nearer to Vynnyky, and by way of detour we arrived in a village.

We arrived at the village and this village was surrounded. The security officers, soldiers made fires to get warm. The lieutenant simply waved from the cab and the soldiers whom he knew let us through. We came to the village and proceeded to a hut in the center, where there were many trucks, soldiers and officers. What is the matter? I jumped down from the truck and bumped into three familiar officers: Vasyl Hlotov, poet, Leonid Prusian, head of the department of the Lviv military district newspaper (there still existed Lviv District) Za Sovetskuyu Otchiznu, and the third one, a major. Well, as far as they knew me (I had been already a winner of a literary contest and they knew me well: the day before I was in their editorial board) they said, “Oh, and you were sent here. I said, We were brought here by chance, they gave us a lift.”—“Something interesting’s boiling here,” they said. Prusian introduced me to the major, Please, meet our special correspondent. This major was a delicate person and stiffly extended his hand, “Major Parsadanov from Krasnaya Zvezda. I asked him, Are you a resident correspondent of Krasnaya Zvezda?”—“No, I am on a special mission here. I asked again, Will you stay long?”—“I arrived yesterday and today I am flying away. I was wondering, what kind of special mission it was: he arrived yesterday and today is flying back?

A tall gray local villager with a big Adam’s apple was going beside me. He said that he headed the village Soviet. He led us into a khata. Inside a killed scantily clad woman was lying on the bed covered with blood. In the cradle lay a baby with an ax in its head: the baby was axed and the ax was left sticking out of its head. From under the bed they drag a seven-year-old: her head was smashed with something heavy. A captain made explanatory remarks: The Banderovetses killed her because her husband joined the Soviet Army to defend our Motherland. I asked again the head of the village Soviet, who stuck to me because I spoke Ukrainian: Was he the only man who was called up for military service?”—“Certainly not, there were about thirty of them.” I began to doubt at once: Why did they kill only this woman and her children in such an abominable way?

And it immediately got through my head who had killed them. What was the purpose of the special trip of this Major, who arrived yesterday and today runs away, why the whole bunch of correspondents and press photographers from Kyiv, Lviv, and Moscow is already here. I understood what was up. My guys saw it too. Then we said to ourselves, Guys, if we go on serving such executioners, blood of those murdered kids will fall on us as well.

After that for a long time we were thinking, talking it over and finally decided to somehow fight underground. For some reason, it did not come home to us that the UIA was near us acting underground! It got us beat, and the security agents kept us under close surveillance. We decided to our own underground organization, re-invent the wheel, and call it “ of Free Ukrainian Youth. There were three of us: Mykhailo Chekeres, Vasyl Myroniuk and I. Later Leonid Pylat joined us. Myroniuk was from Ternopil Oblast, Chekeres from Kirovohrad Oblast, Pylat from the Donbas, and I from Zhytomyr Oblast: we were from different locations. Now we had to write a program and regulations of the organization. We did not have any experience, there was nowhere to get from. At our library, we had both Komsomol and party programs (All- Leninist Young Communist League and All- Communist Party (Bolsheviks)), and I was entrusted with the task: You write something as you can on the subject. And we compiled the program and regulations. Then all of us took the oath and organized this.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: So you wrote a program… Were you not afraid to keep it?

M.I.Volynets: I will tell you how it was. I worked at the headquarters and had more free time and free discharge ticket therefore, I was hiding everything at home. When the organization size reached 14 members, it became a sizeable archive for each made a signed statement joining our of Free Ukrainian Youth. Then the reformation of military units began: some units were disbanded, some units were reinforced, men were transferred from unit to unit. For example, Leonid Pylat (he was an artist, he was partially a Jewish, he was a quick-witted guy) was born in Vinnytsia Oblast, but his parents moved to Donbas. So when faced the problem of keeping the documents in a safe place, Leonid Pylat said, I will go on vacation to my relatives, and I will hide them there. Then we will arrange everything with the command.

We arranged a furlough for him. Hardly had he left, when I was told that he was transferred to another unit and put in solitary confinement. I got a fright: where had everything disappeared? As it turned out, they imprisoned him in a basement, and there was a crack in the wall. He picked it open and fled. He was wanted by the Soviet militia, but they failed to find him. Where did he go? Later I worked in a classified department and monitored it all: he disappeared.

In November 1945, our artillery regiment was disbanded and I was transferred to a separate 12th Signal Brigade connection that maintained communication for the headquarters of Lviv Military District.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And when the organization was created? What was the admission procedure? Where did you hold your meetings?

M.I.Volynets: Our of Free Ukrainian Youth was created in March 1945. By the time our unit was disbanded, it comprised fourteen members. When the question of conspiracy arose, I found memoirs of Honorary Academician Mykola Morozov, former populist. He spent in solitary confinement in Schliesselburg fortress 25 years. He died in the 40s. He exactly depicted the procedure of conspiracy. We introduced the system of threes: I knew everybody, and not everybody knew me, only those who directly contacted me. I was responsible for organization development. I worked at the headquarters in the classified department, I had all reports at my disposal, I controlled all of it.

For a short time, I stayed in the separate 12th Signal Brigade. Here a few men joined the organization. In June 1946, this unit was also disbanded. When Lviv and Prykarpattia districts were merged, our commander Colonel-General Popov was transferred to another district and Army General Andrei Yeremenko became our commander. We were disbanded, I found myself in the headquarters of the Ninth artillery corps of ground penetration reserve of the Supreme Command. The Headquarters was station at the Zymnia Voda Railroad Station near Lviv.

After Pylat escaped, I revised all secret documents to see if there remained any traces of him there was nothing, and it calmed me down. Myroniuk was transferred to Kovel there he created his group of three. Others were transferred to Rivne, also to a signal regiment. It so happened that the members of our organization were already in Rivne Kovel, and in Lviv. Then from our location near Lviv we were transferred to the Moscow military district: at first to Gorokhovets Artillery Camp and then we stationed at the Pravda Station near Moscow.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: But let us go a little bit back. What was the goal of the of Free Ukrainian Youth and what were your concrete actions?

M.I.Volynets: Our goal was written down in the program: to gain independence of Ukraine. Including armed struggle. This was the first item. The second. Propaganda and agitation among Ukrainian youth serving in the army and living Ukraine. We set the goal to Ukrainian servicemen to thoroughly study the new military equipment, because it may be useful to fight. Also we had to disorganize SMERSH agencies[1]. One method we read in Academician Morozov’s book: infiltrate it with our informers. There they could find out places of secret meetings where they instructed their whistlers, so that we could trace their agents.

Then there was a popular book by German writer Hans Fallada Every Man Dies Alone. The hero of this novel wrote himself and dropped anti-Fascist propaganda leaflets. We did not leaflets: we sent them by mail. We sent them to higher education institutions: we obtained addresses from the reference books for the university entrants as if to make an acquaintance with the student. Then, after the war, such way of making friends came into fashion. For example, a newspaper featured an article on a front-rank worker giving her/his address: village, region, oblast and we sent this worker anti-Soviet materials. We did the same sending letters to various newspapers. The sentence also mentioned that I had sent such letters to the Pravda Daily. Such were methods of our struggle. What did we do? We distributed leaflets.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: How did you make those leaflets?

M.I.Volynets: We had a trophy German portable unregistered typewriter and we typed our materials on it. It had a Russian layout.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Did you type your leaflets in Ukrainian?

M.I.Volynets: Right, in Ukrainian. We used “1” for Ukrainian і and exclamation point for ї. Moreover, all letters were handwritten.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Were you afraid? You knew about the huge repressive machine!

M.I.Volynets: Yes, we knew, but we worked very carefully. We never sent letters from our unit[2]. We knew that they might search he region using the postmark. We sent out our letters from other cities. For example, we were stationed at the Pravda Station near Moscow, and not far away there was Zagorsk. Alternatively, we posted them in Moscow. We never sent them from our station, we had followed these rules for a long time already and were careful enough not to leave our fingerprints. At the time, all servicepersons were given sheets of paper to write autobiography in her/his own hand. We perfectly understand why: it was done for handwriting expertise, and you also left your fingerprints in the process.

At the Pravda Station, we organized refusal to eat. The whole signal battalion at the headquarters of the 9th Corps refused to eat their dinner. In addition, the 9th Artillery Corps comprised the whole artillery of Moscow Military District. In 1946 (at the year-end) and in 1947 it was a bellyaching food. We said, How long will you feed us with dishwater? Let us refuse to eat slops. The guys sided with it. Our battalion absolutely refused to have dinner. The corps political department in full force came running, an hour later Colonel Nedyelin arrived. At the time, he was the Chief of General Staff of the Soviet Army Artillery and later became the first commander of the missile troops. Nedyelin came to inspect everything by himself. After this, they stole less before in the kitchen only sergeants and master sergeants were on duty now majors, lieutenant colonels, and heads of departments replaced them. This incident caused a stir: a relevant secret order covered both the army and Moscow Military District. During six months, everything was OK and then the routine resumed its normal course.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Were they looking for instigators?

M.I.Volynets: Yes, they did something for the sake of appearances. There was evidence that the food was really bad, and they called on the carpet all sergeants and battalion officer on duty, senior lieutenant. The battalion officer on duty got a severe reprimand, master sergeants were disrated to junior sergeants, and sergeants were reduced to privates. And that was the end of it.

Then I had to run away from there.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What do you mean by running away from active service?

M.I.Volynets: I was in the army, but I had good relations with the Corps Chief of Staff. It was Colonel Ivan Andriyovych Zelinsky, a native from Vyshnia near Vinnytsia. I begged off, though he did not want to let me go, and he transferred me to Vladimir near Moscow, to the seventh Guards Artillery Division. There, in Vladimir, they also immediately took me the headquarters.

And the reason was as follows. We had one such Petro Vozniuk from Chervonoarmiyskyi Region, Rivne (now the restored name is Radyvyliv). He was also a member of the of Free Ukrainian Youth. He was in the hospital. As far as too many documents had been accumulated by the time and he had to return to his unit already, I made out a ten-day furlough for him without permission of the commander, so that he could take our archives out to his friends. He said that he had good friends there, that underground was still working, and he could hide them securely. I gave him ten days, but two months passed, the third month was elapsing but he was nowhere to be seen. He was declared the all- wanted person and five months later he was returned under guard with the document I had made for him. And I had made this document on behalf of the deputy commander of our unit Senior Lieutenant Gorshkov.

This document was presented to Gorshkov. They covered the text and showed him the signature only, Is it your signature?”—“Mine.”—“Did you sign this document?”—“I did not sign this document. There began hue-and-cry, while I served in Vladimir. They recalled me and brought me back from Vladimir. They took me to confront Petro Vozniuk (he was kept in Butyrka). For some reason the investigator went out of the cell, where the confrontation was conducted, and Petro told me that everything was fine. That is, that the documents were hidden, and I calmed down.

For this, I was given to the fullest: the guardhouse.

Therefore, they interrogated me as a witness and sent back, but not to the division headquarters but to the 26th Brigade as a private radiotelegraphist. There was a library. This library served the 7th Guards Division. The librarian’s name was Pohruzhalskyi Viktor Volodymyrovych. In fact, his first name was Vitaliy and his last name not Pohruzhalskyi but Pohurzhalskyi[3]. They purposely transferred me there because this man was their verified snitch. Is it worth telling about Pohruzhalskyi now?

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Do us a favor, will you? Was it he, who on May 24, 1964 set fire to the department of incunables and manuscripts of the CSL in Kyiv!

M.I.Volynets: When in 1942 the Germans began to bring people by train to Germany, let us tell the whole story, the first people taken on went there almost willingly, because people did not know what it was. The Germans still did not commit atrocities in villages, and did not murder prisoners of war. Some people said, Oh, we were in German prison in 1918, and it was good there. And the youth went to Germany, almost voluntarily.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: And where did Pohruzhalskyi or Pohurzhalskyi come from?

M.I.Volynets: He was a native of the Dunayivtsi Region, Khmelnytsk Oblast, and now I cannot recall the name of his village. He went to Germany and worked in that zone, which was later liberated by the Allies. He was sent to the Soviet zone and there he was recruited. There he worked for SMERSH. And here he also worked for SMERSH. However, it was not a secret for officers, who treated me well, Major Gurov, Major Pivovarov warned me: Be on the lookout for that guy. He was also nicknamed Iudushka Golovlev[4]. The Russian literature reader for 9-10-graders, where Saltykov-Shchedrin’s works were included, contained the picture of Iudushka Golovlev by Kukryniksy[5] he looked like that character and therefore he was nicknamed Iudushka Golovlev. He followed me. I see how he approached me, what questions he put me. When I used to come to the library, he let me walk freely where I wanted. The officers were standing behind the barrier in line to order books, while I was going about freely. He asked provocative questions about Hrushevskyi and others. I perfectly understood the how and why of things. I was still staying in English department of In’Yaz (“In-Yaz” stands for the State Central Courses of Correspondence Learning of Foreign Languages[6]). I graduated from the German department there in 1947-49 and in 1950 I entered once more the English department. I strived to improve and studied math because I hoped to demobilize sometime in the future and pursue my studies. He began imitating that he wanted to learn as well and started getting on the right side of me. However, he had finished a seven-year school only. He seemed to tell the prison officer listening to information given by squealers: “I cannot speak with him because is more educated than I am.”

One evening he came to me drunk. Everybody was already asleep, and I was sitting in the office doing something. He came drunk and kept trying to hug me: “Let us kiss one another. I thought you were a scum like me. Now I know you are a nice man. But it seems easy to you: you were not in Germany and the allies did not repatriate you. Now, let us kiss!” And started crying and kept trying to hug me, drunk. I said, You know what, Viktor, who begins hugging in his cups? I do not like it. I like kissing girls, and not with guys. Go and sleep it off, then come in the morning and we will kiss. His whistle-blowing nature showed in fact, he admitted that he was a snitch, he only did not tell his conspiratorial name.

The boys began to watch him. They found out where the office of the prison officer was. The office was at the end of dark corridor opposite it there was a toilet for soldiers and a joinery. So the guys working in the joinery used to open slightly the door and furtively watched the officer’s clients. Several times, they spotted Pohruzhalskyi. Therefore, it was a sure thing.

Next time he also came inebriated and showed me a student’s card. There was a teacher training college in Vladimir. At the time, it was a two-year teacher’s institute. He flared the student card and said, Here, look, I’ve got a place at the institute, historical department”. I thought for a while, who could enroll a guy with a seven-year school diploma? The more so in February, in the middle of the school year? Obviously, he should have a pull in SMERSH. In addition, I had girl friends at the college. I still have letters from one of them. I said, Masha, I need a background info on a new freshman.” She was on good terms with the dean of the faculty and he said, Ask me harder! Ye was sent by the higher-ups.” I realized that the SMERSH pulled the strings.

I was well aware that if they would recruit someone besides Pohruzhalskyi, they would sign up a guy who slept next to me, with whom I communicated regularly even who was sitting next to me in the dining room, sharing everything, such would be their choice. There was a junior sergeant Zelisko from Chernivtsi Oblast, it seems, from Novoselytskyi Region. He studied mathematics with me physics, and different languages. When it became evident that he was my close friend, I asked him, “Ivan, do you really want to learn this or you were planted by the officer?”—“Not for the world: I would spit in his face.”—“Cool down! They will sure summon you and try their best to recruit.”—“And I will refuse,” said Ivan. “On no account you you’re your consent and then come and tell me when they recruited you and what task they set.”

Just 10-15 days later Ivan came running and said anxiously, “Mykhtod--Mykhtod was and is my name in the village--you can see through a millstone!”—“What happened?”—“I am straight from the officer.”—“Which one?”—“Captain Pichugin.”—“And what was what?” He told me… On the eve of these events we saw the dugout, but couldn’t figure out why the dugout? For what purpose was it built? “He saw me in the dugout we had seen.”—“And what about him?”—“He tried to recruit me.”—“Did you agree?”—“I did.”—“What’s your conspiratorial name now?”—“Smart.”—“Who’s your target?”—“I should keep watch on you.”—“Well. When is your next contact?”—“In a week, the same time.”—“Where?”—“Over there, in the same dugout.”—“Well,” I said, “a few days from time we will concoct the tip-off together and you will carry it to him. What questions did he ask?” He told me. I played the officer’s way and dashed off the report and Ivan simply rewrote it and carried to the officer. The next day I asked, “Well?”—“He was not very happy with the job he said they knew that you were so and so, while I reported nothing special.” Next time he wrote in my presence. Then he used to show me, I revised the text and carried it on. We were putting it across for over a year.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: You had a tamed snitch!

M.I.Volynets: Before we had a couple of such guys: Hrysha Berezhnyi from Chernihiv Oblast. He worked for a long time, from the very beginning. This time it was Ivan. Later we identified all safe houses and tracked down Pohruzhalskyi. We found 18 informants. Some of them we were beating in the dark. Then his neighbors, his countrymen rejected him. You know, they often ran to the officer and said, I do not want to because they gave me a thrashing in the dark and my countrymen rejected me.” The regulatory authorities became worried. Captain Pichugin summoned me as well and tried to recruit me, but I made a row he just said, “I’ll get even with you.” And he clenched his fist. I went away.

Arrest. Investigation. Special Council

(April 3, 1950--February 7, 1951)

The demobilization was just round the corner. It was already announced that privates born in 1926 and sergeants and privates born in 1925 would jointly depart towards Kyiv on April 5. I stayed then in the medical unit. On April 3, they discharged m from the medical unit. I came to the battery and the battery commander ordered me to fill out soldiers’ “cards of penalties and rewards”. But here came a messenger from the Staff, Private Dvorovyi, Volynets, you’re summoned to the headquarters. Well, I was often called to the staff: to draw a diagram, a secret document, they knew that I had security clearance. I went without my greatcoat as far as the staff was located on the first floor. The barrack-room was on the second floor, and the staff was down on the first. On my way, I ran into Major Khomenko, commander of the third anti-tank battery, Going to the staff? I said, Yes, sir.”—“Why are you without a greatcoat and headdress?”—“It is not that cold at the headquarters, sir. It is April now.”—“It’s me who called you, we’re going on a duty journey.”—“What do you mean by journey, sir? The day after tomorrow I am going home!”—“We’ll be there and back, we’ll return tomorrow, take your greatcoat and headdress.

I prearranged it with Ivan that if something happens to me, he will check my bag, take and destroy its contents: the program, rules, letters of application, Zelisko’s receipt. I took it just in case if he were planted to imprison me, then he would eat dirt as well. Later it played a role. He gave me a signed statement like the one he gave them. This might look later like I had provoked him.

I went and took my greatcoat and hat. “Go, go!”—“Where are we going?”—“To Horohovetski military camps. This is our summer camps. I said, “But the train leaves in the evening, why should we run there in the morning?” And he said, “They changed the train, the new one will come”. Well, I understood everything. We ran out of the stationing area, passed the control post, the checkpoint. Wow,” he looked at his wristwatch, “we shouldn’t be late. Maybe someone will give us a lift.” And looked back. I also looked back: who could give us a lift? Everything might fall into place if it were a KGB paddy wagon. Oh, our car. Maybe they’ll give a lift. And I saw a paddy wagon. I realized that this was an arrest.

The vehicle came to a stop. Deputy Head of Division Counterintelligence Major Israilev got out and invited me to get in the back seat. And this Major Khomenko also got in. They got in and the car started. We arrived on the main street of Vladimir—Moscowskaya Street. Along the street there were various stores, shops, hairdresser’s and one door was for military personnel only and no one knew what really was there. We approached the door. The door opened and it turned out that it was an entrance to the Vladimir Kremlin where the KGB counterintelligence was. Khomenko said, Comrade Major, can I be free? And I answered him instead of Israilev: You have done your job, you may be free. He cowered and ran away.

We entered, but the security guard let the major passes but not me, because I had no permit. He started persuading the guard, but the guard jibbed. So I said, “Comrade Major, if I am not permitted to go on, I may go for walk in the meantime.” I turned back to the door and major, like a kite, outstretched his hands: Where? Where? Where?” Then he arranged it on the phone and the guard let me in. There they arrested me, stripped shoulder straps, removed my belt and brought through another entrance right to the Vladimir jail.

This was on April 3, 1950.They brought me to the Vladimir jail, but not to the big political detention center hanging over Moscowskaya Street, but to a smaller transit prison not far from our unit. They brought me there and shoved into an empty cell. There were many beds in the cell, my nostrils were immediately assailed by the stench of rotten cabbage and tobacco.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Were there beds or bunks?

M.I.Volynets: No, there were separate iron bunks. And there were folklore inscriptions scratched on the walls: The incomer, cheer up, the outgoing prisoner, do not rejoice and the like. I spent the night there. The rats kept running like horses, peeped, they smelled awfully.

In the morning, Major Izrailev called me for the first examination. His first question was, Name your friends.” I grasped: if I call my close friends, especially the members of the organization, some of them may be scared and tell God knows what. The officers may give them a sound licking and they might stumble. So I named the already known men: went Pohruzhalskyi because he was in their eye and we allegedly were friends, next was Zelisko Ivan Stepanovych, then I named a few guys with whom I had served in the army and who had long been demobilized.

On the second night I was transferred to the cell with a political prisoner. His name was Penkov, he was a re-arrested former Trotskyite. For the first time he was arrested in the 30s, but then released, and now it was his second arrest. This Penkov taught me cell wisdom, how to behave. However, I already knew that. We spent only one night together. I was transported under guard to Moscow. In Moscow, directly from the railroad terminal, they drove me to Butyrka. In Butyrka, of course, they stripped me naked. And the first thing that surprised me—or maybe I would rather pass it in silence—was the command: Bend down and open your anus.” I did not know how to open it automatically and the jailer explained: Take buttocks with your hands…” Well, he looked inside and found there neither guns nor grenades. As I started to dress a sergeant came running and showed a piece of paper. Get dressed, be quick! They dressed me and shoved me into a truck like Dodge, in the past there was such US haulage truck with the truck body with canvas cover. One armed security officer sat on the front seat next to the driver while I sat on the floor and two security men guarded me with submachine guns. They said, Don’t gape about! It was 6 or 7 April in Moscow, women without outerwear… well, I gaped by stealth… Sitting in the truck body a saw everything like in a frame: Spasskaya Tower, Kremlin star, Kremlyovskaya… I was lost in guesses where I was taken. They drove me past a monument to Pushkin, Pushkin Square, and another monument--later I found out that it was a monument to Vernadskyi. They led me then through backyards, the logs lay scattered. I saw a sign: “Krasnyi Voin District Newspaper, organ of the Moscow Military District. I wondered why they brought me to the editorial office of the Krasnyi Voin. Several times, I’d sent there my poems under the pseudonym of Ivan Malakhov. There existed one such: I wrote poetry under his name and he received honorarium. I thought that they want to show them what enemy they apprehended, which had worked for them.

They led me up the stairs to an office on the second floor. Inside there sat a typist at the entrance, a chair in the corner, then the door to the next room. Those doors shook in all directions: everything rattled and somebody made the air blue. Well, I thought they swore at someone like me when they would be through with him, they would curse me. Then the door opened and out popped Lieutenant Colonel Volgin, my commander of SMERSH counter-intelligence of the 9th Artillery Corps. I had the face to say, Ivan Petrovich, how do you do? He sweat and looked at me wild-eyed, furiously waved his hand: “E-e-e and out he went. Only during the re-examination, I found out that because of me he was fired for his incompatibility with the office requirements: he overlooked me.

And here came three colonels. The first colonel seemed familiar to me, the other one went beside him, and the third stayed behind. I do not know what kind of an editorial office it was that they swore at the counterintelligence chief shouting at the top of their voice. Let us go. They led me along the corridor. All of sudden we saw other agents leading someone towards us, and my sentry started snapping fingers. At once, they turned me to face the wall. At this moment I saw their wall newspaper before my nose: “Official of Cheka. Organ of the Counter-intelligence Department of the Moscow Military District”. Then I realized what kind of the editorial office it was!

They led me to Major General Popov, who was at the time chief of counterintelligence of the Moscow Military District. They took me to the office and the colonels chose to stand as follows. The one who led the way stood beside the general, another one stood against this wall, and the third one stood four steps behind. Sit down, please. I sat down on a chair at the long T-shape table covered with red cloth where the general sat and with green cloth at my end. I was at the bottom of the table. The general was very busy, he was writing something there, but I noticed from afar a pile of my diaries and letters before the general on the table. The colonels kept silent and he went on writing. Then suddenly the general looked up sharply, “Well, tell me your story”. I calmly said, What story, Comrade General?” I still told Comrade General”. Tell me about your criminal activities!”—“I was not involved in any criminal activities, so there is nothing to tell. Ask me questions, and I’ll answer.”—“Our investigators will ask you questions.”—“Well, let them ask then, I’ll answer.”—“Well, stop playing cat-and-mouse with me. The general came up to me, and I wore three soldier’s blouses, all of them without buttons. (This was Penkov’s advice, and the sergeant major had just distributed new blouses). Therefore, he took a new tunic, Oh, the new duds, heh? And who did it?” I said, Why are you asking? The workmen did it such as our fathers and mothers.”—“That is the Soviet people? I said, “Yes, Soviet subjects. I did not say Soviet people but Soviet subjects.”—“Well, it’s no use discussing it with you. We’ve got three questions only. First. “I do not want to have anything in common with you,” and we will know how to handle you. The second question. “I want to return to our Soviet Society.” Then we might find the way out. In addition, he made such a gesture. And the third question concerns your repentance. So now what? Make your choice and speak out.” I said, These are too complex questions that must be thought over.”—“If you are not answering at once, you will tell lies.” And he turned to the colonels: conditions for him and let him think it over.”

I came out of the general’s office, and the convoy was already there: sergeant and two soldiers. They led me down into the basement of this editorial office and showed me my bare plank bed. I lay there until the evening, the soldiers gave me gruel to eat and in the evening hey transferred me in a paddy wagon it was not a usual paddy wagon jam-packed with prisoners but there were individual grated cages. You had to curl up to sit there.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: It was called a glass.

M.I.Volynets: Yes, and the light shone into your eyes through a spyhole. They brought me somewhere, stopped, I just tried to quickly count the floors: one, two, three, four… seven floors altogether. They led me somewhere. During the examination I asked where I was.—“You will be told. You will be told, no one said anything.

We took the elevator up. The polished parquet floors shined. They brought me into a corner box. There was a bench the jailers brought me two duvets and down pillows this would imitate my sleeping berth at the lights-out time. Go off to bed. I looked at the bench trying to figure how I could fit in. If I lie down on this bench, my feet will project which is very uncomfortably. I put one duvet on the floor and lay down on it. At once they opened the door and said, Get up, it is not permitted, lie down on the bench. And I had to squirm on this duvet. Well, there were many funny incidents, when they led us to a latrine…

V.V.Ovsiyenko: They call it shitter in the jail.

M.I.Volynets: I was very impressed by the fact that there were no special openings in the door for gruel dispensation. The dispenser came in a white cap and with a tray: “Your dinner, sir. At first I thought he was mistaken and did not get up to take the tray, but he repeated: This is your dinner, sir. I took and ate. Their grub was better than the fress in Vladimir. He observed me through the spyhole. When I finished eating the man in a cap came in: Dishes, please.

So I lived for five days, although I had problems with sleeping. I wanted to see the prosecutor or investigator. The investigator called me he had a big belly with fingers thick like sausages. He said, What did you make a lot of noise about? I’m your investigator, major, you see my rank, my name is Novosyolov, I’ll conduct your case.”—“Well, let it be.”—“Why did you call me?”—“Because the bedding was inadequate and I needed to sleep.”—“You are not in a cell yet you will have enough sleep there.

I spent one more night there. As a matter of fact, the investigator said, My boss wants to meet you. Colonel Afanasenko managed the investigation department of the third main directorate, his office was in the neighboring room. And this one, too, was sitting there like the general at the T-shape table. He was very busy and could not answer my “good day”. Then he raised his head, Tell it! And I, Tell what?”—“Tell about your criminal activities!”—“Ask me questions and I will answer.”—“The investigator will ask you questions.”—“Let him do it. Immediately he began intimidating me, We know everything.”—“If you do know, why are you asking me?”—“Take him away.”—“Somehow you didn’t get along with the chiefs, said Novosyolov, when we returned to his office. Why do I have to get along with them?”—“It means you’ll soon find yourself in a cell.

I was transferred to the cell, but not there, in the Lubyanka, but the paddy wagon brought me to Lefortovo where they shoved me into a cell on the third floor. There were three bunks, but I was an only prisoner. It was good in Lefortovo because the toilet sink was in the cell and there was no marching to the shitter. I was there alone for a long time. The investigator called me only once. They brought to my cell an inmate: sickly, small, in military uniform, without shoulder straps. He introduced himself: Major Alexander Ivanovich Petrov, from Krasnaya Zvezda, assistant chief of a department, something like battle training”. He asked me, Are you a reader of Krasnaya Zvezda?” I say, “I used to read it regularly when it was available.”—“Whom do you remember?”—“Lieutenant Colonel Troyanovskyi, Major Parsadanov.” I met the latter near Lviv. He: Oh, Parsadanov! We lived nearby, he used to come to me, my sonny sat on his lap, played with him and it was he who sold me out, you know? I could never even imagine it!” And I thought at the time: he had sold you out and you could sell him out as well. I did not indulge in confidence with him. Well, he started in a roundabout way telling about Kyiv, Shevchenko Boulevard, and I said, “You know, I lived near Kyiv but I never was on Shevchenko Boulevard. I used to roll by Kyiv going by train and I saw there nothing more.” He told me something about poplars, began to write poems there, asked what poets I liked. Well, I said that most of all I liked Shevchenko. “Oh, Shevchenko… it is not my scene, while Blok…” Whom else did he mention? He mentioned Bryusov and somebody else. In fact, it was not his personal preference but standard Moscow hierarchy of ranks and grades: service record of Russian poets of the twentieth century. The first like marshals. Mayakovski was generalissimo, marshals included Blok, Bryusov, Tikhonov and some more. He put them in order of rank, after the corporals and privates the rear was brought up—excuse the word—by sheer shit.” Anatoliy Safronov was among the latter. I realized that this man was not an easy meat.

And again they put in our cell a student of military institute who studied French and Farsi: Kosterin Gennadiy Alexandrovich. They both were communist party members, praised Lenin very much, were afraid to abuse Stalin, because Stalin was still alive. They highly praised all and everybody they could get on.

Then they brought master sergeant Alekseyevskiy from Yaroslavl near Moscow. He told that he was a member of the military band playing at the Teheran conference when Stalin presented Churchill with the sword from Stalingrad. And he told an anecdote how Lenin found himself in paradise. Have you heard this anecdote? Can I tell it?

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Tell it, please, if it befits the situation.

M.I.Volynets: Right, let it be… So, Lenin died. Well, he knew that he could not be admitted to the paradise for destroying churches, killing priests, he was a notorious sinner. He went straight to the hell. Once he appeared in the hell, the devils rebelled, “Out of here!” And they threw him out by the scruff of the neck. “You will arrange a revolution here, we do not need this.” And they drove him out. He sat down at the crossroads and stayed there deep in thought: What will become of me? No way to go. Here came Moshko with a bag, “Volodya, why are you sitting?”—“Well,” Lenin said. “I’ve got a sort of trouble, devils ousted me from the hell, and the road to paradise is barred to me, because I am a great sinner.”—“Let’s go now, I’ll fix it up.”—“How will you do it?”—“Get into the bag.” Lenin got into the bag, Moshko shouldered the bag, went to the gates of heaven, and knocked at the gate. Peter was already sleeping there, the door was rusty because for a long time there were no righteous men. Peter went out and saw Moshko. What do you want, Moshko?”—“Tell me, is Karl Marx here?”—“He is here and what do you want?”—“Pass him this junk,” and handed Peter the bag. Thus, Lenin found his way to paradise.

Alekseyevskiy told this anecdote, and the next day the jailers called Petrov, and a day after they called Alekseyevskiy. And Petrov told me: “You see how this scum spoke about Lenin. So everything was put in its place and Petrov lost credibility with me. And this Alekseyevskiy was taken away immediately. Later there were several newcomers, but then I was also taken out.

The investigator, who conducted my case, had already seen in my diary, how I entitled Stalin: “His Cannibalistic Majesty Joseph the First and the Last.” The investigator told me: You may be bumped off only for this”. Obviously, my investigator, Major Novosyolov already knew whereto I was attached, and therefore spilled the beans. It turned out that sometime in the past he served as a border guard together Mykyta Karatsupa. Have you ever heard about him? In the 30s, before the war, his name was in everybody’s mouth: in the Far East he nabbed more than three hundred frontier crossers. It turned out that this Novosyolov, my investigator, changed guards with Karatsupa on the state border. And he told me how Karatsupa was made a hero. I did not force him to say it, but he told it of his own volition.

They picked out this proud, but narrow-minded Khokhol, and we went with him to the same dog-breeding school to train our dogs.” The name of Karatsupa’s dog was Inhus. We changed each other. Many a man from Manchuria forded the Iman River. Many foreigners wading across the river remained unknown for us. A month later, the locals told us that there were relatives from abroad, but we had no idea about it what were we doing there on the border then, which way did we look? We should raise morale for everybody to see that the border was under lock and key. It was resolved to back Karatsupa. They brought a man from a faraway frontier post, because all locals knew us very well. They posted him on the border and issued him a following order: “Go to the City of Iman or to the theater, or to the market, any other public place.” Then they put Karatsupa with his dog on the scent. Just imagine: during the film show the duty detail burst in and the dog charged at a viewer. At the last moment, it is pulled back. The viewer raised her/his hands and everybody witnessed it: even in the market or in the theater nobody could get away! In this way they made Karatsupa a hero.”

This story I heard from Novosyolov, my investigator. There were some more interesting things.

Then I was transferred to another cell. I stayed there about a month. So they transported me from Lefortovo to Lubyanka. And this Novosyolov was on vacation or on a business trip to Ukraine. He was in Korostyshiv, in Zhytomyr, and in Kyiv. In Kyiv, he interrogated Halyna Sholina, People’s Artist of Ukraine[7], because I had a letter from her. He wanted to know whether she knew me. How could she know me? They interrogated everybody to establish whether there existed such an organization as the of Free Ukrainian Youth. However, in Kyiv and Zhytomyr everybody maintained that they were not in the know.

Meanwhile, other investigators interrogated me. Lieutenant Vartanov was the first to call me. They brought me and made me sit down on the penalty bench all of a sudden an athletic-type man in a T-shirt burst in: Hi!”—“Well, hi.”—“I was passing by and saw a man having a tedious time. I thought I could exchange idle words with you! - So he told me. And he started asking questions about my case. I said, Sorry, but I do not give evidence to a passer-by.”—“What do you mean? I am your investigator.”—“You told yourselves that you were just a passer-by.” Well, he moved about and began to wag his tongue: “Have you seen the new uniform of militiamen?” And I had already seen it: it looked like the uniform of a tsarist gorodovoi[8]. “They are introducing it now in Moscow, Leningrad, Sverdlovsk, and Baku.” And I said, I beg your pardon, but are you Azerbaijani?”—“And how do you know?”—“Everything points to that.” By the way, I had a good friend, a cohort who served in Lviv, Heydar Aliyev.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Hang on! Was he the same fellow who was a member of the Politburo of the CC of the CPSU and now is the President of Azerbaijan?

M.I.Volynets: Right, the same man. As a master sergeant, he was a deliveryman[9]. Many Azerbaijani boys were in the army. “Yes, I am from Baku.”—“Well. I saw this uniform before my arrest, but it resembles that of the tsarist gorodovoi.”—“Well, it’s a national tradition! And I said, In Moscow, in Leningrad it is a national tradition, but how can it be a national tradition in your Baku?”—“But we all are fraternal nations now!”—“Well, let it be, but all the same the nationalities are different.” He looked at me in a strange way and phoned somebody. A football match was in full swing and he ran to the stadium.

Next time Captain Malyshev called me. He had already called me two times, but this time he officially introduced himself and questioned me.

After that, they moved me to another cell. I entered the cell: again Petrov, Olexiy Mykhailovych, the second cellmate was Yerokhin Hlib, and the third one was a German with some very common name, but he kept silent. It turned out that all of them were Soviet intelligence agents. Petrov was a resident of the Main Intelligence Directorate in Prague, Yerokhin was his agent in Prague and he was recruited before the war. His father was a yesaul in Cossack army, in the 20’s he emigrated to Prague. The yesaul’s son, Hlib Fedorovych Yerokhin, was recruited as a gymnasium student. In Czechoslovakia, he rose to the rank of lieutenant of the KGB[10].

Why was I shoved among them? Moreover, all of them were partners in crime, untried… Maybe they intended to bring me around or to scare? I do not know. I stayed there for a week, and Petrov told me very interesting things. He talked my head off. I wrote about him in my memoirs. He told me how the fixed the February revolution in Czechoslovakia in 1948[11] when Gotvald replaced Beneš. This revolution was organized by the first secretary of the Soviet embassy, he was a KGB resident and Petrov was a resident of the Main Intelligence Directorate. This new first secretary showed him the document when he assumed office. The document read: issued to such-and-such who is appointed the first secretary of the embassy in Prague instead of a deceased one. And the date of appointment… it was the date, which indicated the day before the death-day of the previous secretary.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: They were convinced that he should die…

M.I.Volynets: Right, they knew for sure that he would die. He told many stories of this sort. He also told who and how engineered the outbreak of Finnish War: two colonels and general were first to shell Leningrad in 1939. Well, there were other stories he told.

However, I stayed there about a week and was moved to the corridor of death as it was called. There I spent six weeks. I knew nothing about the progress of the case. They did not even inform me that they concluded the investigation. Novosyolov said, “Well, let us sum up now.” But they did not let me read the file. They did not hold an identification lineup with Zelisko whom I recruited. He was not even mentioned in the case.

From December 1950 to February 1951, I stayed in the Lefortovo without trial on death row. In February, they took me to Butyrka and shoved into the cell with three cellmates. Two of them came to me Shenderovich and Pilitovich, officials of the Ministry of Procurement of the USSR. The third one was sitting with downcast eyes and not even looking at me. I asked why he was so indifferent? They said that he was a Frenchman. I reckoned it was a joke and asked whether he was a Berdychiv Frenchman. No, they said, he was a real Frenchman. Why is he so strange?”—“Because--they said--he did not understand Russian.” And they did not speak French. It seemed he spoke German, but they could not speak with him because they did not speak German. I was surprised that the Jews did not speak German. I came up to him and said hello in German. He sprang and grabbed my hand with his hands, tears ran from his eyes, he was trembling and answered me in German: Oh, I beg your pardon, I’m crying: I have been kept here for two years now and there is no one to exchange a few words with.” He learned in Russian only the word cabbage because they fed us with stinking cabbage. In fact, it happened when the freight elevator was operating it lifted cabbage and the Frenchman pronounced imitating Russian pronunciation “kapusta”.

I will tell no more about doings and stories told in the cell. They called me and led me down to a tiny room. There was a small table inside and a lieutenant colonel with the same yellow face, which showed that he seldom walked in the fresh air. Sit down, please,” he pointed to the opposite end of the table. “Read, please”. And he gave me an extract from the resolution of the Special Council. I read it. Below there was a signature of a secretary, the format of my sheet of paper. He was looking at me intently, and I understood why. According to the memoirs of Dyakov and others, having read the verdict the condemned always began shouting: I am not guilty, I like Stalin more than anyone else! They cried, were filled with indignation, and I smiled calmly and asked, Is that all? And he pouted as if he failed to understand me, Yes, yes. I said, “Must I sign it somewhere?”—“Yes, yes, do please.”—“But there is no place for my signature.”—“Overleaf, please. I turned it over and there was a free place and I wrote that I had read the extract and calmly asked again: “Should I also put a date?” And he looked at me incomprehensively as if he was frightened and said, Yes, yes, date it, please.” Well, I dated the document and that’s all. * (* M.Volynets was sentenced by the Special Council on February 7, 1951 under art. 58-1b, 58-10 p. 1 and 58-11 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic to 25 years in prison.—V.O.)

He buzzed the jailers, they led me to the cell, and here an unexpected error occurred: I met a woman in a dark suit. She was beautiful, tall, slender, her skirt reached barely below the knee. We met, greeted, and this old hag that escorted her, wardress, the old partlet! The woman was shoved in one direction, I was shoved in the other, and the guards there kept quarrelling for a long time trying to establish who was to blame.

They led me not to my cell but to a mass cell, where they kept the convicted prisoners.

Transportation

(March 1951)

At the beginning of March 1951, directly from Butyrka my transportation began. They led me down the stairs to the common-type paddy wagon, where a serviceman was sitting. We met, I was also in a greatcoat, though without a belt and buttons which we made of bread. We dried and sewed on these buttons of bread. This man was Davydov, a military physician from Sumy. He told me tis and we began to converse about who and where did his term and in what cells. He was also in Lefortovo. I said that I did my term with Petrov. Petrov? Scum, stoolie! I asked which Petrov he meant because I stayed with two cellmates named Petrov. “Alexander Ivanovich, from Krasnaya Zvezda. And the second one was intelligence agent Petrov.”—“That one from Krasnaya Zvezda is a scum. So he told me. Our conversation was over, because the jailers brought other convicts. They brought Rabinovich, chief of the technical department of the Ministry of Geology, Romm, communist party organization secretary of the Ministry of Geology and Alexander Zonin, writer from Leningrad. Zonin had already been doing his term in Karaganda[12] he was summoned as a witness in the case of a friend of his and now he was on his way back. They admitted me to their company. There were also several Germans with us.

Zonin told me a very interesting story. He told me privately as follows: Try to imagine: you arrive at the camp and there you see Vlasovites, Banderivetses… Do you know that lot? I thought that they reform these people that they make Soviet people out of these nationalists… In actual fact, they are rallying there, publicly oppose comrade Stalin and Soviet power. When my patience was exhausted--I was a miner, you know—when my patience gave away I went to the prison officer to hear his explanations. So, I went to the prison officer and told him about these irregularities. Just try and guess what the prison officer replied. The prison officer told me, Do you think that we do not know? We know this very well. They do as they will, and we are in the minority and cannot do anything. And here is my advice to you: when you go from me, beware lest they see you. Because I do not give you a guarantee that tomorrow, when you go down into the mine, a piece of rock will not on your head and you will not come to see me again.” This was the advice of prison officer to this Zonin Alexander Illich, the author.

In Chelyabinsk, we were separated from Zonin and others, and Romm and I proceeded to Taishet.

Chuna. Escape

(Spring 1951--August 1954)

From Taishet they transported us to the woodworking factory, to Chuna. Here was the son of General Tarnavskyi, Myron Myronovych. His team included Volodymyr Tsaryk from Lviv. He found me because he knew that I served in Lviv, and knew Lviv very well. Tarnavskyi was a team leader at the electric power station in fact, he was a chief manager of the electric power station. It was warm at the station and nobody overtoiled there it was by far not a lumbering job. They were eager to engage me but the excessive formality and routine interfered with the decision and then I was sent to the dimension-timber shop manufacturing collapsible walls for prefabricated houses. Well, we talked things over: it also was a warm conveyor work and I stayed here. If it comes to the push, you come to me and I’ll engage you,” said Tarnavskyi.

I worked here until the Kengir and Norilsk uprisings. Various rumors reached us and some witnesses came already.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: The insurgents were transported to different camps…

M.I.Volynets: So we also began to establish contacts. But how? In the shop, we could make it only through the civilians. With this end in view I went to work at the bucket shop, where freight cars and vehicles arrived I could establish contacts there. We established contacts with the women’s colony in Vikhorevka. Our people were transported there and from there the convicts were brought to us.

Then the time of change set in in Moscow, Stalin died. It was rumored that the government commissions for re-examination of the cases would be created.

We decided to run away, but there remained the team to burn down this woodworking enterprise. They did set fire to it, but something went wrong and soon the firemen put out the fire. Yefim, a Mordvin, organized the arson. And we—I, Leonid Kotenko, Anatoliy Kuralin, who did his term in Dubrovlag afterwards--we went after the breakout. The five of us went along the duct three of us managed to reach the end of it< while Dmytro Movcharuk and Petro from Volyn buried under the debris. Somehow, they managed to get out and return back leaving their things there.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What kind of duct it was?

M.I.Volynets: Our prisoners were building a club in the zone for free employees and garrison. The central heating was provided by boiler-house system in the zone. The heating pipes were sheathed with planks that formed a duct where there remained enough space for a man to struggle forward. Under the overpass, we made a secret passage and tested whether we could crawl there. The total distance to cover reached up to 300--400 meters. Three of us made it, but Kotenko, who brought up the rear, blocked up the entry way and the two guys following him had to return they had but to leave their things because they could not rescue them. So they hurried to come back during the interval between night shifts. They left their belongings. And we need to know about those things not to give them away because the officers tried to find out from us who accompanied us.

They caught us when we tried to ford the River Chuna. We held on to the raft, which the rapid current crashed against a barrier invisible in the dark and Kotenko cried out, Save us!” We were surrounded by the boats with armed locals incited by the KGB officers they apprehended us and handed over to secret agents. They brought us back to this column and put us into the medium security barrack. Well, I went on a hunger strike. Seven days I went without food and imitated that I could not even stand up. They sent a medical orderly, brought me to the medical unit, where they injected me glucose, gave food to me and two days later they had to transport us to a Taishet prison for trial. The guys from the zone besieged the medical unit and through the window passed five bags of products for all of us. They also provided winter clothes for our group so we went to Taishet with excellent outfit.

We were tried (on August 25, 1954.—V.O.) by the Irkutsk Circuit Court. Under art. 82, p. 1, of the Code of Russian Federation they added three years to each of us.

Ozerlag

(1954 - 1956)

We were sent to the penalty 43rd zone even near Bratsk, where the Anzyoba Station was being built. There we refused to go to work.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: What kind of work was it?

M.I.Volynets: We had to go and build urban settlement Anzyoba near Bratsk[13]. So we only went to the zone, but did nothing there. We tried to size up possibilities for escape.

On the way, I met a Macedonian, who lived in Greece. He served in the army of General Marcos: the Communist Party organized an army that fought until the 50s[14]. In the army of General Marcos he was deputy brigade commander in charge of policy and educational work. He is a poet, I still have a poem in his handwriting his name is Petro Rakowski. He was a delegate to the First Congress in Defense of Peace held in Paris and Prague: those who were refused visas to Paris gathered in Prague[15]. He was in Prague and told me about it. He joined us and he did not go to work too.

We found out that from all Ozerlag they brought all foreign nationals to the colony no. 43 and all subjects of the Soviet were sent to other prison camp sites. Before I had never seen Ukrainians from the eastern diaspora--from Manchuria and China--and now I saw two men. The name of one of them was Pavlo Yakhno he was also a member of the government of the Transbaikal People’s Republic[16]. He served his term in Chita in 1920[17], where he was put by Cheka agents. Then they fled he headed the Ukrainian Prosvita in Kharbin[18]. The second one was Mykola Odynets, professor, he was an adviser to Puyi, Emperor of Manchuria[19]. I wanted to come to know them and to talk with them. So when I was called to be transported under guard, I told the orderly that such-and-such was going to work.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Mr. Volynets Metodyi continues on June 4, 2001.

M.I.Volynets: When the jailers came again and called my name, all and everybody shouted in unison: Why do you bother us? He went to work. During three days, I conversed with Yakhno and Professor Odynets. They told me about the Trans-Baikal People’s Republic, about developments in the Zeleny Klyn in 1918-20, told about their work in Manchuria, and about Prosvita. It was very interesting for me, because I saw Ukrainian immigrants from the Far East for the first time. After that I went to the administration on my own initiative and told that I’d remained alone one among foreigners, and I was sent to the 06th colony to work in a brickyard.

Here, at the brick factory, I was assigned to remove recently fired bricks through the outside door of the Hoffmann kiln at the temperature of 70-80 degrees. The workers wore felt boots, quilted trousers, fur caps with earflaps and special glasses to see everything. The prisoners worked there in turns. I immediately said, “Chief, I won’t be able to work here for 25 years, I will not go there.”

The guys helped me immediately. There were many people from Ukraine. Foreman Petro Shkurynov, Belarusian journalist from Mazyr engaged me as an assistant fireman for firing bricks and molding. And so I worked there as an assistant fireman.

There was a more organized underground group already. Ivan Vasyliovych Dolishniy[20] was the man of authority. He was a supra-regional OUN leader of Zhydachiv supra-region he was taken prisoner unconscious, wounded. Then they damaged him one eye. Subsequently, this colony was closed as unprofitable and the transferred me to the same woodworking enterprise, where I started my penal servitude on Chuna. But these were the other times. New people were arriving who had already done two years in the maximum-security jails, after Kenhir, after Norilsk. Ivan Hryshyn-Hryshchuk--also a writer, he now lives in Vyzhnytsia--came from Vladimir maximum-security jail, Yurko Sakharov came. He lost his arm in Norilsk, he was a known chess player, master of sports, before the war he was many times Champion of Ukraine[21].

We began working to close ranks of prisoners, but the jailers did not know the first thing about it. When the administration called someone, he took a minimum of two witnesses with him to let people know what he was asked and what he was answering. The informers were taken away from the zone, because there were big furnaces at the electric power station, where they burnt sawdust, once the convicts caught one such Bukharov with the report to the authorities and another former KGB officer, team leader, who did his term in our colony, and they disappeared without leaving a trace. So they were all afraid.

I worked as a ledger clerk in the accounts department and the chief accountant was free. His son, captain, served in the operational group he used to say, It beats me: my security officer complains all the time that we know nothing. What’s boiling here by the way?” I said, Mykhailo Ivanovych, it’s good when they know nothing.

We made it so that our free team leader or superintendent knew nothing about the disposition of the labor. We figured out ourselves who would work the night shift, who the second, and who the first. We arranged that the man worked the night shift not during the whole week, as previously, but two or three nights. In short, we controlled the daily routine. Without our consent the administration could not arrest anyone, for the moment they arrested somebody the whistle sounded, everyone stopped working, and they had to release the convict into the zone.

Commission. Re-investigation

(1956 - 1957)

In Chuna, the state commission for post-conviction review had already started working. It was already in 1956. This work began in June. The release of convicts was carried out on a mass scale: each day they called about 30-40 people and released almost all of them.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: How many convicts were there in your zone?

M.I.Volynets: There were close to 2,000 people. They released them on a mass scale. The plant was not fulfilling the plan already, therefore they brought people from all neighboring zones.

In September 1956, this commission did not release me and made no decision in my case I had to stay. I was repressed by the Special Council, and the General Prosecutor’s Office appealed against all decisions of the Special Council. Therefore, at the beginning of October 1956 they summoned me for re-investigation at the Lubyanka. Around October 7 - 8 the investigator told me that Ostap Vyshnia had died.

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Ostap Vyshnia died on September 28, 1956.

M.I.Volynets: Right, in 1956. This re-investigation lasted until June 1957. The investigator was again Yevhen, but the first time it was Novosyolov, and now Yevhen Zernov. Prosecutor Arakcheyev was the chief military prosecutor. I even joked: In my case all people have names according to Pushkin. The investigator asked, Why? I know Arakcheyev, but who is Zernov? I told him Pushkin’s epigram[22]: Romanov and Zernov, you’ve hit a snag, you two are of a kind: Zernov, you’ve got a lame leg, Romanov’s out of mind.”—“Oh, you know Pushkin!”—“Yes, but I studied in the Soviet school.

My relationships with the investigator were not very friendly, I did not bow and scrape before him. Therefore, they played a trick on me. They summoned me to a separate cell by my count, fourteen people were sitting there. The major general presided the lot. There were also my prosecutor Arakcheyev, my investigator Zernov, several colonels, lieutenant colonels, and majors. One of them asked a question and didn’t wait for my answer, when the second officer present hastily asked his question. However, I was a tough customer and I said, Wait, please, I will answer the first question, then I will answer you. Arakcheyev showed me a letter from an Odesa University student. They did not find her because she wrote under the pseudonym Larionova Larysa Larionivna or “L cubed”, it was her alternative signature. They failed to find her. I wrote in Ukrainian and she wrote in Russian. So, you are a nationalist, she wrote in her letter. The prosecutor said, “Look here: “nationalist”, you make a clean breast of it.”—“I beg your pardon, citizen prosecutor, it is not my letter. You interrogate the author of the letter and find out her motives to say so. And secondly--I told him--decent persons do not read other people’s letters. The prosecutor jumped as if he were stung: Decent persons do not write anti-Soviet propaganda in their letters.”—“Show me my letter, please. It’s not my letter why do you accuse me based on someone else’s letter? However, the general said, Arakcheyev, won’t you sit down?” He was a lieutenant colonel, this Arakcheyev. The general took him down a peg they did not tell me anything and took me to the cell.

You may know that immediately after Stalin’s death there were several processes: allegedly, they caught Karavanskyi, who was sent to Moldova[23].

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Yes, Svyatoslav Karavanskyi was imprisoned immediately after the war[24]…

M.I.Volynets: No, it was a different man. In Norway, Halai and Skvortsov were caught. So, I met this Halai over here. The regulations allowed sleeping to your heart’s content in the afternoon. Everybody was left to himself. Then the students began arriving who protested in Moscow against the occupation of Hungary, sons of big wigs. For some time I had a cellmate, Anatoliy, son of the head of agitation and propaganda department of the CC of the CPSU Alexandrov.

The officers took me to the identification parade. They brought three of us, seated on chairs, there was even one civilian sitting he had to identify who was who. He recognized his brother: there was one such Rybak from the Stavropol Krai, who served in the Soviet Army in Germany and fled to the British zone and lived in London. After Stalin’s death, the Soviet embassy there published propaganda newspapers: Come back, your Fatherland is waiting for you!

V.V.Ovsiyenko: Your Motherland will forgive.

M.I.Volynets: So, he left there his family and came here to visit his mother. Meanwhile the death sentence awaited him here, and then they reduced it to ten years.

There was also one serviceman and Barykin, developer of firearms. He invented a new rifle or something, and presented it to the Ministry of Defense for patenting his invention. They turned down his invention and issued a document that it was of no interest to them. So he sold it to the French. Then they imprisoned him: you yielded the French a new weapon! This was the fourth time that he was taken to court and he told them: here’s the expert’s report.

And this Volodymyr Halai, which was extradited from Norway, told how he escaped from Austria to the American zone, where he graduated from the American intelligence school. His teacher was a major of the Soviet Army, who had crossed the border 12 times in both directions and then became an instructor at their school. His mother lived in Gelendzhik, Krasnodar Krai, near Novorossiysk, and his father lived in Irpin near Kyiv. This Volodymyr Halai did his term in Dubrovlag. The officers brought him albums with photos of those abroad who were of interest for the intelligence. He thumbed through these albums to see if there were the pics of his acquaintances. In the cell, he was given newspapers to read (he was a convict). When the jailers shoved me into this cell, they used to take him away to read newspapers in another cell. Lieutenant Colonel Krotov used to come to our cell--later he signed my release—and we told him, “Lieutenant colonel, sir, he comes back to the cell and tells me all the news. What is the point in taking him to another cell? Krotov said, You’re right. Even before he finished his cells round on our floor, the jailers brought us Izvestia Daily. Halai had camp albums with songs and poems, and I wrote in it in a verse form a letter to my future wife. He subsequently sent her my letter from Dubrovlag. I also received from him three letters from Dubrovlag.

I was tried by the Court of Moscow City Military Garrison. The presiding judge was Lieutenant Colonel Sikachov, Arakcheyev was my prosecutor. The supervisor said, Oh, thirty minutes drive there and then we’ll go back.” Well, let it be: the sooner the better. They again summoned to witness this Pohruzhalskyi and Nina Antoshchenko, Zelisko they brought from Karaganda (at the time, I jotted in my loose-leaf memo book: 1, Peschanaya Street). The adjournment. The first day of trial ended.

On the second day, the prosecutor insisted to give me time to the fullest, not to grant pardon. Honestly, my attorney at law there was neither one thing nor the other. By the way, I waived the lawyer, because I hated this procedure. The judges went to the decision room. This room looked like this: the scene and the booth for judges. They filled the place with smoke and opened the door. The supervisor said, Well, it will take 5-10 minutes more and we will go to dinner.” However the chewed the fat for thirty minutes… one hour… no end in sight. The door opened and among many different voices I heard Lieutenant Colonel Sikachov summing up: If the prosecutor lodges the protest (he certainly spoke in Russian), we will lodge the counter-protest that there is evidence past and current, secondly, everything is proved by documents, thirdly, the analysis of his criminal activity was carried out based on his diaries.” I heard it all myself and decided to lodge a protest as well. The meeting of the judges lasted four hours.

I returned to my cell and said, Guys, eight years. I had already done more than seven years and they took into account a couple of months subtracted from my term. In a week or so the eight-year term expires, exact calculation. The guys said, We will wait and see. * (* On May 16, 1957 the military tribunal of Moscow garrison reviewed the case of M.Volynets and passed a new sentence under articles 58-10 and 58-11 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR: eight years of corrective labor camps and deprivation of rights for three years (art. 31). This sentence also absorbed the unserved part of the sentence of Irkutsk Oblast Court from 25.08.1954. Since the beginning of the term was counted from the date of the first arrest on April 3, 1950, it meant discharge.--V.O.).

On the second or third day I was summoned by Lieutenant Colonel Krotov: The prosecutor has lodged a protest against the decision of the tribunal. Will you put in an application?”—“I will.”—“How many sheets of paper do you need?”—“Two sheets, please.”—“will it suffice?”—“I won’t draw a picture, you know.” He opened a separate cell: an ink well was on the table. I just repeated the counter arguments of the presiding judge addressed to the prosecutor.

At large

(June 22, 1957--September 19, 1980)

Nearly two weeks passed by and on June 22, 1957 * (* The certificate issued by the KGB prison under the Council of Ministers of the USSR about the release was dated June 21, 1957.--V.O.) I was summoned with my things to go nobody knew where. God knows whether I would go home or would be taken back to the camp. There were students of the Bauman Moscow Institute of Technology doing their terms for protests against the occupation of Hungary, and this Rybak. I said, Let’s make an agreement. I leave here my toothpaste and toothbrush. If they intend to transport me under guard, I will say that I have forgotten them and you will bring me them, because there is nowhere to get them. But if I go home, I will not need them.” And we settled on that.

They brought me to Lieutenant Colonel Krotov, Deputy Head of Lubyanka prison: “What is your station of destination? I said, “Zhytomyr. He: Your travel documents to Zhytomyr station are ready.” He gave me per diem expenses for two days: two karbovanetses and a few kopecks, eighty-five or something. He issued me per diem and an order for a ticket. They led me through four doors and let me out from the KGB, but not here, onto the Dzerzhinsky Street, but on the back of beyond, on a side street. They showed me where to go: there you will find the underground station Dzerzhinskiy and from there you go to Kievskaya station. I went out of the underground station and got lost. I also had this suitcase, you know…

V.V.Ovsiyenko: A wooden trunk, probably.

M.I.Volynets: Yes, a wooden trunk with angle pieces and braided handle the guys did their best to manufacture it and varnish. I met an approaching passer-by, said hello, and said, Please tell me, where is the underground station Dzerzhinskiy?”—“Dzerzhinskiy? He looked so scared and then pointed with his finger: “Over there”. I looked in that direction and saw a black arch: Dzerzhinskiy. I went to the station. Arrived at the underground station Kievskaya, went to the railroad terminal, and then saw enormous lines… I started asking people, they said that they had been waiting there for three days already because the tickets were not available for sale.