V.V.Ovsiyenko: On April 5, 2001, in the Prydniprovske Town, mother Nadiya Sokulska (maiden name Hryvnak), wife Orysia Vasylivna Sokulska, daughter Marichka Sokulska and his friend Serhiy Aliyev-Kovyka, who made the tombstone cross to Ivan Sokulsky, are telling about him in the khata of the mother of Ivan Sokulsky on the 3, Marshal Konev Street, and on the cemetery. Vasyl Ovsiyenko is recording.

MOTHER.

N.I.Sokulska: Nadiya Ivanivna Sokulska. My father’s last name was Hryvnak. We lived in a hamlet, 50 km from here. We moved here in 1967.

V.O.: How was the hamlet called?

N.I.Sokulska: Chervonoyarskyi.

V.O.: What region did it belong to?

N.I.Sokulska: Synelnykivsky.

V.O.: When were you born?

N.I.Sokulska: I was born on January 5, 1921.

V.O.: It fell just about Christmas?

N.I.Sokulska: Right. I am eighty years of age now. In 1967 we moved here. I had been working for 34 years at the collective farm and then I worked for 20 years here, because as a collective farmer had no right to a pension: for the length of service at the collective farm was not taken into consideration while determining a pension plan. Like so. It happened in the same year, when they did not want to take Ivan on. I must say that he finished the seven-year school here, in Mykhailivka and then studied for three years in Synelnykove and graduated from the ten-year school there.

V.O.: When did he graduate from the secondary school? He was born in 1940 he became seventeen years old in 1957 or 1958…

N.I.Sokulska: Somewhere like that. Then he went to Lviv as he wanted very much to enter the university. His agnate uncle told that he would provide funds for his education upon his graduation from the secondary school. Upon graduation from the secondary school, he hesitated what higher educational establishment to join. He went to Lviv and worked there for three years in the mines. He entered Lviv University.

V.O.: The Ukrainian philology, right?

N.I.Sokulska: He studied there for two and a half years and transferred to Dnipropetrovsk. At first, there was nothing out of the line the young people followed him and even used to come down to our hamlet once he was shown on the box. In Lviv, you know, he organized caroling on the Eve of the New Year, the groups went to congratulate the administration. And then everything went wrong, everything was off the track and in 1966 he was excluded from the Komsomol and expelled from the university.

V.O.: In what year was he?

N.I.Sokulska: He was in his third or fourth year. Most probably in the fourth. He studied here one year, and then next year he was expelled. And then he was not allowed to work in the specialty. He went on board a motor vessel and worked as a cashier did to save up some money and go somewhere. And he was arrested right there and they even did not allow him to at home. They tittle-tattled that he pasted some posters or leaflets in Kyiv, and for this he was detained. They arrived here and conducted a search always looking for God knows what they took away all written material. His investigating officer also came here it seems their names were Zhyvoder and Huslystyi. They kept sniffing out and asking me questions all the time.

Ivan was jailed here, in Dnipropetrovsk. I carried him parcels, I pestered his investigators, prosecutor, and KGB officials requesting visit permission. I told them: “You’re beating and torturing him there.” I went to my sister and she stuck to her guns: Oh, he’s put us to shame!” Has he killed anybody or stolen anything? And her husband: He is in for a rough ride. All those convicts are tarred with the same brush.” Well, you can’t be always at home, you know… So I went through channels and asked them: And you just show him to me. You’re beating and torturing him there”−“What do you mean!” they answered. “No one may hurt him there.” Nevertheless, they let me to meet him before the trial. He looked so beautiful. I carried him good parcels.

And then, they announced a secretive trial and we retained the services of lawyers from Moscow though to no avail! Only I was allowed to be present in the courtroom. Even his brother was not allowed. That’s about the size of it. I do not know what else I can say.

V.O.: And what do you remember from the trial: what was it all about?

N.I.Sokulska: What was it all about? They summoned Skoryk, Savchenko. I did think that they were guiltier than my Ivan, but it turned out otherwise, and then Ivan was sentenced and they were set free. Mykola Kulchynskyi also did his term with him. He was also sentenced for nothing: some girls told lies about him and recanted their testimony during the hearing of the case they maintained that it was nothing but their conjecture. They saw that they had accused an innocent person. Well, they gave him four years and a half and transferred him to Mordovia. Every year I used to travel to Mordovia to have a meeting with him.

V.O.: And what was the number of the zone: wasn’t it the nineteenth zone?

N.I.Sokulska: I am afraid I have forgotten, but I think it was the nineteenth.

V.O.: Lyesnoy Settlement?

N.I.Sokulska: Lyesnoy.

V.O.: later I was also kept there, from 1974.

N.I.Sokulska: Lyesnoy, Lyesnoy. It certainly was Lyesnoy, because previously there heated goods van ran that had later been replaced with the rail car. You arrive there and they tell you that the rail car run has been cancelled, and you by dint of your own haul that baggage because you have to survive on it for three days. People helped. The moment I came for a visit Huslystyi was already there: If you had told me early enough, I would have…” They never allowed giving him a parcel.

V.O.: And who was he, this Huslystyi?

N.I.Sokulska: Investigator, the one responsible for the pre-trial investigation. He stuck around there all the time. What ho.

He did his term over there and then, at the very end, he was transferred to Vladimir. I went to Vladimir when they were about to release him. He wrote to me asking to come in time for the release. And so I went. I arrived there and saw a colonel sitting there I asked him: Well, will you release Sokulsky? But they are not clued in about Ukrainian. He isn’t registered with us.”−“What do you mean? Here is his letter.” You know, my hands were shaking. “Go to the parcel control department and they will tell you about his whereabouts.” I went there the woman on duty looked at me and said: Look here, lady, and take it easy, he is in Moscow Serbsky Institute.” Well, now I had to find that institute on the very day of his release. I took 11 a.m. commuter train, because they clicked in at nine, and there was this 11 a.m. commuter train. There I saw decent people sitting I turned to them and a woman gave me a note. I asked her how I could find the institute. Usually before the trial they send a person to the institute to examine his or her ability to act and in our case they sent him to the institute after he had done his term. They said, Well, lady, it will be hard for you to find. However, I got up they got up too, took me things, went to the information desk, got the information slip and hailed a taxi for me. I had fallen into good hands with a God-given talent.

They seated me in the car, it wasn’t a long drive, we passed Kremlin, several side-streets, and there was the Serbsky Institute. The taxi drove away and I went in. I entered: a captain was sitting there. I asked: “Is Sokulsky here? He consulted the register and said: Yes, he was. He was brought in under date so and so and taken out afterwards to Butyrskaya Jail. Now I had to get my butt in gear and look for Butyrskaya Jail. I came out on the street and there was a tall blond man walking down I turned to him, he looked at me and said: “I will accompany you there, lady. So God sent me such good people. Also he took my things, we went to the subway by underground crossing, it took us a long time to train in the subway, and finally we went by trolley-bus we arrived at half past four to Butyrskaya Jail. I entered the building and saw an information desk I asked: Is Sokulsky here?”−“Yes, he has been sentenced to four years. The thought flitted across my mind that he was tried again and adjudged for some mess he had done. I said: He did four and a half years from beginning to end, they were about to release him.” She started to ring around and then said: Yes, they are filling out the discharge documents for him”. Well, at least the situation clarified and I found my son. At 18 pm he’ll be at the gate.” I kept pacing up and down there being on pins and needles. They invited me to sit there, but I was on edge, you know…

At six sharp he came out. He threw off his quilted coat and changed into clothes that I brought with me.

V.O.: Was it in summer?

N.I.Sokulska: No, not in summer, but before the New Year.

V.O.: And four and a half years, yes.

N.I.Sokulska: Before the New Year. They gave us an escort to take us to the railroad terminal, buy us the ticket and put us on the train to prevent our going about Moscow.

V.O.: Yes, they did it on purpose.

N.I.Sokulska: Its a sort of enemy. This guy took us to the Kyivsky Railroad Terminal, rushed about for some time and then said: “Here are ten karbovanetses, get yourself a ticket.” Ivan laughed, took those ten karbovanetses, and we went to the Kursk Railroad Terminal. He also had a bag of books ht stored it in the baggage room and we went to Leningrad. A priest, his friend, stayed with him in the concentration camp. We to his mother there were his father, mother and brother. We stayed with them for a while, bought up things and went home. So that is how I was looking for my son for the first time.

V.O.: You did find him.

N.I.Sokulska: Heavens, I found him. Ivan did his term with Orysia’s brother Yaroslav Lesiv. He went there, met Orysia and married her. And so Orysia and I have been living here in harmony for 27 years now and granddaughter, my Marichka lives with us. And that’s that. What else can I say?

V.O.: What can you tell us about that period when Ivan was here at home?

N.I.Sokulska: He had many friends. Savchenko and Halyna came, Skoryk with Tetiana, Zaremba… quite a lot of them. The Kuzmenkos used to come frequently: he was on friendly terms with all three brothers. But only he was found guilty and he had to serve his term.

V.O.: Why only one? Prykhodko, Petro Rozumny and Mykola Kulchynskyi were also found guilty and sentenced.

N.I.Sokulska: Rozumny used to say: No, I will not be jailed, I am not like you.

V.O.: They jailed him, though.

N.I.Sokulska: With what did they charge him? As opposed to Ivan, they adduced a knife as evidence.

V.O.: These pros found with what. He traveled to Siberia to exiled Yevhen Sverstiuk. Yevhen had already done his term and lived in exile. Petro made two trips there. Therefore, in order to cut his visits they jailed him.

N.I.Sokulska: So, they jailed him, didn’t they? Yes, Rozumny was a constant guest.

V.O.: Now let’s get over to the second case. At the end of which year was Ivan released?

N.I.Sokulska: Ivan was released at the end of 1973, because he got married in 1974, and in 1975 Marichka was born.

Mommy, in your fabled city

the blue sky is so deep...

Youre alone and all your pity

lashes windows like a whip.

Youre alone and shades grow darker,

as the fate of son grows starker.

Mom, Ill take a ride

and meet my garden.

And each son on Whitsuntide

will lead bride alike the guardian.

All your guests are nice and witty,

the blue sky is so deep...

Youre alone and all your pity

lashes windows like a whip.

V.O.: When did Ivan wrote this to you?

N.I.Sokulska: He wrote this poem to me after the first trial… I was under impression of the trial and memorized it at once. I had a good memory then, while now I am very forgetful.

V.O.: Okay, then we will continue our conversation later, and now let’s visit the cemetery before the dark.

Orysia Sokulska and Serhiy Aliyev-Kovyka

V.O.: Mother recited this poem in the kitchen garden. Now Orysia Sokulska goes on with the story. We go to the cemetery accompanied by Serhiy Aliyev-Kovyka.

O.V.Sokulska: Oryna Sokulska is the wife of poet and political prisoner, dissident Ivan Sokulsky. I have the honor to introduce now Serhiy Aliyev-Kovyka. He is the artist who published together with Ivan nine issues of Porohy, cultural and artistic almanac of Prydniprovya[1]. Serhiy made the tomb cross as the monument to Ivan.

V.O.: Mr. Serhiy, tell us, please about the making of the monument.

S.Aliyev-Kovyka: It had to be done and I did it. This was done as the spirit moves one. I felt the significance of Ivan, thought about our relationship and it made it possible to do so. It was not made to order. It was been an extraordinary creation for me, probably the work of my life.

V.O.: What are you doing now?

S.Aliyev-Kovyka: We are making books now for example, here is Letters to Mariyechka (I.H. Sokulsky. Letters to Mariyechka: Selected Correspondence (1981 - 1987). Compiled by Oryna Sokulska, designer Serhiy Kovyka-Aliyev.—Kyiv, Smoloskyp Publishers, 2000.--92 p.--With a bouquet of dried flowers and herbs sent by his daughter Sokulsky I.H. Letters to Mariyechka: Selected Correspondence (1981 - 1987). The book is illustrated with early pictures of Mariya Sokulska. Compilation and notes by Oryna Sokulska. Designer Serhiy Kovyka -Aliyev.--Dnipropetrovsk: Sich Publishers, 2000.--87 p.)

V.O.: Did you design all of them?

S.Aliyev-Kovyka: Two editions: the first one is black and white with the use of the grass blades sent to Ivan while he was kept in the concentration camp the second one is a color edition with the pictures of Marichka. The first book of poems by Ivan Sokulsky The Definition of Liberty is a collection of poems. (I.H. Sokulsky. The Definition of Liberty: Selected Poems. Compiled by O.V.Sokulska. Designer S.Ya.Kovyka -Aliyev.--Dnipropetrovsk: Sich Publishers, 1997−351 p.). My photos and layout. Now we are working to publish the correspondence. (I.H. Sokulsky. Letters at Dawn: Bk. 1 Epistolary heritage 1980 - 1982, documents, photos. Compiled by Mariya Sokulska, designer Serhiy Kovyka-Aliyev. - Dnipropetrovsk: Sich Publishers, 2001.--517 p., Bk. 2. Epistolary heritage 1983 - 1988, documents, photos. Compiled by Mariya Sokulska, designer Serhiy Kovyka-Aliyev.--Dnipropetrovsk: Sich Publishers, 2002.--507 p.).

O.V.Sokulska: We are going now to go through the Village of Chapli, the birthplace of Valeryan Pidmohylny.

V.O.: Here is the Shyyanka River… And I know where the grave of Valeryan Pidmohylny is: it is in the area with the field name of Sandarmokh in southern Karelia. I was there last summer. In 1937, in Sandarmokh, 1111 prisoners of Solovetsky Special Purpose Jail. The Ukrainians were shot and killed there, basically, on November 3.

Already at the grave of Ivan Sokulsky: There is a Kozak cross of white stone with the inscription “Blessed are they that have been persecuted for righteousness sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” Matthew 5:10. And on the stone: The poet Ivan Sokulsky 13.07.1940−22.06.1992.”

S.Aliyev-Kovyka: I’ve already told you about the cross now I’ll tell you about this tombstone. I found this stone about six months before the death of Ivan on the far bank, in Prydniprovsk, where Ivan and I used to go in the past. Sometimes we used to build a fire and cook kulish[2]. I found this stone in the reeds. In the sand, half buried in sand. Our forefathers erected these menhirs about six to eight thousand years ago, or maybe more. These menhirs set on the banks of the Dnipro our ancestors who lived in these places. This is a historic standing stone representing almost anthropomorphic image. I told Ivan about it when he was already ill: we planned to go there, but his strength failed him. However we talked a lot about the find and discussed variants to salve it, because it could vanish forever. Somebody could take it to make foundation or it might sink in the sand in the reeds. When Ivan was gone, we decided that as far as Ivan could not come to it (it stood at one or two kilometer distance), we would put it near the grave so that it would be with Ivan forever.

O.V.Sokulska: It is very big.

S.Aliyev-Kovyka: Yes. The underground part is almost as big, and it widens toward the base. This is a real menhir. As far as I can professionally explain menhir, it is an anthropomorphic stele that is a hewn stone with no carved images yet. This is an archaeological term: menhir[3].

V.O.: What peoples had menhirs and what is their dating?

S.Aliyev-Kovyka: They are very ancient: starting from eight thousand years. Menhirs may be found in the steppe across Europe and in the steppe reaching China: these are menhirs, the preimage of sculptures. They were succeeded by kurgan stelae.

V.O.: It means that these menhirs are older than kurgan stelae?

S.Aliyev-Kovyka: Yes, of course, at first there were menhirs which had no anthropomorphic carvings it is stone hewn on four sides, a sort of stele.

V.O.: Thank you. When we were in Kuchino, in the Urals, Ivan was very often kept in punishment cells. Then we were transported from Kuchino to the Vsekhsvyatskaya Station. It was exactly on December 8, 1987. On this very day Gorbachev met Reagan in Reykjavik and Gorbachev had to lie at least for one day telling that they were not there already. So on this day, December 8, we were transported to Vsekhsvyatskaya. The majority of us had been kept out of cells already and Ivan remained in solitary confinement, and almost always they used to put him in the cooler. There were also Mykhailo Alexeev, Petro Ruban, Mart Niklus, and Ivan Kandyba. But Kandyba was kept there for less time.

O.V.Sokulska: Ivan liked to repeat that we went through the jails together. Ivan loved his family very much. Ivan was a sucker for life therefore he survived in solitary confinements and coolers. He knew ways how to draw himself up.

Today I want to say that I have a moral obligation to open Ivan’s entire creative legacy, all his works. I think that readers and his contemporaries must make an appraisal of his works. We dream that one day Ivan’s diaries will be out and they will tell his personality in the making and how he wended his way through life in this Russified country. You know, he started writing in Russian, and only later he came to Ukraine and came to God.

MOTHER

V.O.: We are again in Prydniprovsk, 3, Marshal Konev Street, apartment of Ivan Sokulsky’s mother Nadiya Ivanivna Sokulska. Present is Orysia Sokulsky. Present is Serhiy Aliyev-Kovyka. Please, tell us about the time when Ivan was at home after detention.

N.I.Sokulska: He went to the Carpathians, our wedding took place in 1974. At the time of second arrest, I was in the kitchen garden and was busy planting potatoes on the tenth of April (1980--V.O.). So they came up to me: Go and open your house. I went however not to open, but to tap at the window and say, Get up, because you’ve got guests. They arrived early in the morning, before 7 a.m. there was a whole carload of people. They brought all their weight to bear on the door, broke off the lock and rushed inside. I’ve got no idea what they were looking for. They went over the kitchen garden probing with rods. Did they think he might hide weapons, or what? Well what he hid?

And so without a word they took him away. Once we came to see him here, in Dnipropetrovsk. They carried out the hearing in private and said nothing either to Orysia, or me. What else can I tell you? And they sentenced him then, we were not present at the hearing and we knew nothing about the punishment itself, we came to know about it only from his letter. Orysia beat down doors but nothing could be done.

V.O.: Did you go at least once to meet him? He was in Tatarstan, or wasn’t he? In Chistopol?

N.I.Sokulska: We went not to Chistopol, but to Perm. It happened in the same year as our atomic power plant exploded…

V.O.: The Chornobyl Disaster took place on April 26, 1986.

N.I.Sokulska: So, we arrived in April and we were there on the First of May. We thought that due to the holiday we would be allowed to stay longer, but on the First of May, they drove us out. We went on foot, because then there was no transport to the commuter electric train.

V.O.: It was in the City of Perm?

N.I.Sokulska: No, it was in the zone it is not far off if you go by electric train.

V.O.: Was it in Kuchino, right?

N.I.Sokulska: Yes, in Kuchino, must be Kuchino. We traveled by train to Moscow, arrived in Perm by plane and then went by commuter electric train. We arrived there, but stayed for the night somewhere nearer here, because, unfortunately, Orysia forgot her bag in the train, but they found it and returned.

V.O.: How many days were you allowed staying with him?

N.I.Sokulska: Three-day meeting, so we stayed there for three days.

V.O.: You were with Orysia, right?

N.I.Sokulska: Orysia and Marichka, there were three of us. I never went there afterwards. She did go there, and I did not. He returned in 1988.

V.O.: Did they search you when they allowed you to meet him?

N.I.Sokulska: Yes, they did. They searched me in a perfunctory manner, while Orysia was searched very carefully as she said. When I went to visit Ivan in Tataria, they did not search me at all.

V.O.: In the jail you met him in the room for visits or you were talking across the table?

N.I.Sokulska: I spent three days with him, three days. Sometimes they called him back to work, sometimes not. Once I went with a junior son, he also took music with him, but they took it away. For three days only and the time runs fast. Once I forgot my passport: I arrived in Moscow without my passport. All people have to have passports and I had none what was to be done? So I went to the militia and asked them, said I did not know whether I had forgotten it at home or lost, or it had been stolen, I had no passport while going to see my son. However, they called and told me to come and that I would be allowed to meet my son. I arrived and went to the chief, he gave me a sort of document and for three days I had no right to go out. During other visits I could go out, I had to leave my passport at the pass-through and then could go out this time I had no passport and therefore had to stay inside for three days. Well, it did not matter the main thing was our meeting took place. There were Lithuanians who could go out and they brought us everything we needed.

V.O.: It seems to me, Ivan was released on August 3,1988…

N.I.Sokulska: Right, it was still warm.

V.O.: Did he arrive unexpectedly? Weren’t you expecting him?

N.I.Sokulska: Right, we were not expecting him. He did not write a letter, he just arrived without notification. The first time he wrote to me and asked to come.

V.O.: Do you remember how it was? When Ivan came, where were you?

N.I.Sokulska: We were at home and he came with one of our relatives. I was at home when he arrived.

… In fact, I grieved but nothing could be done. In this hopeless situation I cried day in and day out? Nothing could be done, we had to take a hold of ourselves, we also had to forgive and remember that God helps those who help themselves.

V.O.: Yes. Apparently, many a people came to you.

N.I.Sokulska: After he arrived, oh, our khata stayed open, because time and again somebody stayed for the night. There were several visitors, several friends, many people dropped in to see him.

V.O.: Where has he lived recently? At home?

N.I.Sokulska: He was in Mechnikov hospital. I wondered why highly qualified contemporary doctor and everything so advanced and they could not cure him. When the next day I came to see him, it was on Sunday, and there were his friends. He said: You see, Mom, I am already healthy. They administered him a lot of drugs for the weekend. He said: You see, I am up and going already. He was sitting there and looked chirpier. Then we took him home… At home he used the oxygenous pillow Marichka went at night to fill it. And he died in hospital. He was hospitalized again. They too upon themselves both casketing and cosseting: he lay there for three days and looked better dead as alive. All Ukraine came to pay honors during the funeral. I really could not see anyone, but a huge crowd descended there. But he is no more, and nothing could be done.

V.O.: I know that Mykhailo Horyn was at the funeral.

N.I.Sokulska: There was Horyn and there was his brother as well.

V.O.: Bohdan Horyn, Levko Horokhivskiy, Mykola Horbal, Mykola Samiylenko.

N.I.Sokulska: There were many, many people and the burial was very well arranged. They wanted to perform the funeral service for him in the cathedral, but you know those Katsaps… We had to pay, without payment we were not let in and the funeral service was carried out on the steps of the porch of the cathedral.

V.O.: Really?

N.I.Sokulska: Then they carried his coffin past the Mechnikov Hospital and down the streets of the town. It was a well-orchestrated funeral, but alas he is no more… And now many friends come in memory of him: they come to commemorate his birthday and on Remembrance Day. I am very grateful to his many friends they have published his book, there was a telecast and they remember him in radio broadcasts.

V.O.: I have visited many people here in Dnipropetrovsk, and everyone has a good word to say about him, they mention him with reverence. By God, they commemorate him as a holy man.

N.I.Sokulska: Thank goodness! When he was doing his term his cousins repudiated him. Thats the way the mop flops, they were afraid, for if the officers found as much as our address, they summoned the person to the KGB: both nephews, and cousins, everybody. Therefore they were afraid. I told him repeatedly: My beloved son, son, why aren’t you grooving on reality?” I am scared even to remember the collectivization…

Well, what sort of life was this? We were brought from Khmelnytsk Oblast: four small kids. Petro was eight, but he already had to go and till land together with his parents, because fifteen hundred square meters of land needed cultivating. And three other kids stayed at home: I was five, Fedir was three and Olena six months. Just imagine leaving three naughty kids at home! If they had taken us with them, the swarm of midges would have stung us all over… Therefore I used to tell Ivan : Sonny, why aren’t you grooving on reality? And then there was the collective farm, dispossession of kurkuls, sell-out… Lord forbid! Then our father took us to Zaporizhzhia, we overwintered there and returned to the village. So, I know my life very well and I’ve seen nothing good in it. Well, I thought that I would spend my old days at ease and with no worry but everything went wrong. In 1938, I married, in 1941 the war was levied Ivan’s father was enlisted for the army. At the time Ivan was still a baby. He wrote letters from time to time. He felt good he worked as a material man at a property stock. There were ten or fifteen were letters and then bombardment followed and he disappeared.

V.O.: In what year did he disappear?

N.I.Sokulska: The officials wrote that in 1943, and nobody knows for a certainty. I wrote to Moscow, from Moscow they sent me a notification. Now you see what were made of! Why haven’t we turned to us?”−“Because its as broad as its long and you won’t lift your finger all the same, but I still want to know where my husband is.” Therefore they wrote that he was missing. And this is life.

And Ivan grew up a very cheerful and a sensitive boy and, oh, he studied well. He finished seven-year school in Mykhailivka, where my brother was the principal. He fought in the war went and returned, and my junior… They were driven to Zaporizhzhia and were not even given a uniform and all of them were killed in action in 1943. Such is my life and there is nothing for it. One should take a hold of oneself, and−God grant it!—not to take to one’s bed. Everything is smack on, but my blood sugar level is high. And I have no daughter now, my daughter-in-laws are good, with Orysia I lived 27 years. Its a long way to travel together, isn’t it?

V.O.: Thank you.

N.I.Sokulska: Thank you and thank you for your trouble, I am grateful to all his friends who are still calling on me. Serhiy has manufactured a beautiful cross with his hammer.

V.O.: Yes, a nice cross.

N.I.Sokulska: Over there in the kitchen garden.

V.O.: Did he hammer it here in the kitchen garden?

N.I.Sokulska: Then they brought it to the graveyard and erected there.

V.O.: Thank you, now I’ll go over to Orysia and talk with her.

N.I.Sokulska: Thank you. It’s a heartbreak, but that’s that, we must take a hold of ourselves, ask God to never have a day’s illness, not to take to bed, but try and walk I am eighty already. Thank you, thank you, go to Orysia now.

WIFE

V.O.: Finally, Ms. Orysia will speak.

O.V.Sokulska: I always thought that our history would be put on paper when all of us would have passed away. But there are still his flesh and blood: wife, daughter, mother and I thank Mr. Vasyl Ovsiyenko for his interest in this issue, and I thank those who collect memories.

If I may plunge into history, in the past, I would say that I was ready to live as fate willed. Due to the fact that I was born in the Carpathians, my father was involved in insurgent resistance, my khata in the Carpathians was a place where people used to gather and discuss all topical issues. And we, children, listened with half an ear to those talks I, my late brother Yaroslav Lesiv, my sister Anna were hiding somewhere deep on the sleeping ledge, when our mother urged us, Its time to go to bed. Bye-bye!. And when I came to Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, I met Sokulsky and I knew what Ivan was doing, what he wanted, I was a nationally-minded person. I was hardened by Carpathian Mountains and my family.

V.O.: What was your home village?

O.V.Sokulska: My native village was Luzhky, Dolyna Region, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Yaroslav Lesiv and I, Oryna Sokulska were born there.

V.O.: When were you born?

O.V.Sokulska: I was born on March 10, 1952. Not far from us lived Zynoviy Krasivskyi. He lived in the nearby Village of Vytvytsia, where I finished high school. He was a very close friend of our family, Zynoviy Krasivskyi. Yaroslav Lesiv, Zynoviy Krasivskyi, Panas Zalyvakha, Ivan Sokulsky used to come together in the intimate circle. Yaroslav got down to politics in real earnest, he was busy reviving the Greek Catholic Church, as well as Zynoviy Krasivskyi. Panas Zalyvakha was preoccupied with his artwork he was a man of art. Ivan Sokulsky was an East-West man in Dnipropetrovsk, but fate bound us. Zynoviy Krasivskyi once spoke of a Japanese garden, which he dreamed to somewhere in Hoshiv, where all intellectuals could come together, where all honored retired people could stay, where they would be able to a small academy and conduct open discussions.

This was the circle of my friends recently. Although during democratic perestroika we found ourselves in different circumstances. Ivan was a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki , then the Ukrainian Republican Party, and I, so to speak, picked up the baton from him. I was in the Ukrainian Republican Party until a new wind of changes began to blow. I took a walk, when they proposed KGB General Marchuk as a presidential candidate. I could not line behind this candidate. All of our family was persecuted, exterminated, and killed by the KGB and suddenly they start to bull me that this man is beautiful, kind and democratic. I had no reason for complaints concerning him as a man, but he was a KGB general, and this fact told its own tale.

Such were our differences. Apparently, it is a sort of inconsequent reasoning… I was a village girl from the mountains, and then, perhaps, I should say honestly and frankly that Im happy that fate brought me here.

V.O.: Was it your brother Yaroslav who acquainted you with Ivan, right?

O.V.Sokulska: Yes, they did their time together in Mordovia. I remember the last letter of my brother, where he wrote that he had a good friend there, who would come to visit him at home. And it was a miracle: Ivan arrived in 1974 to visit Yaroslav in the Carpathians. Everything happened with lightning speed, there was good chemistry on us and he soon made a proposal of marriage to me. Perhaps he was looking for a kind of me, and I may have needed exactly this person.

V.O.: Mysterious are the ways of the Lord.

O.V.Sokulska: I think its my destiny, and thank God that I have settled down. I would not say that Ivan was easy to get on with, but it was never dull with him. He was a very extraordinary man.

I cannot tell about his first imprisonment, because we were not married yet. By 1974, he did four and a half years. But about the second stage I can tell a day-by-day story, because I know all pains, all blackmail that were used against him, against me, against the family, even against my child. The second term as regards the Ukrainian Helsinki Group I take upon myself as well because it was my life.

V.O.: May you be more specific, please, about the events from the first and till the second imprisonment.

O.V.Sokulska: I came here in 1974. We got married, I became a wedded wife of Ivan. We got married in the Carpathians, in the Village of Lypa, where Vasyl Kulynyn had been born.

V.O.: I have recently spoken with Vasyl Kulynyn in Kherson Oblast.

O.V.Sokulska: We got married on August 4, 1974. After that we moved to Dnipropetrovsk. Ivan had to work as a fitter at the Pivdenmash[4], not far from here. Then the vicissitudes set in and he began changing jobs. Two or three years went by more or less peacefully, although it was difficult to remain calm because he had to report to the militia, because he was sentenced to one year of administrative supervision. Occasionally the bodies of power used to summon him for talks and interviews. But when the Ukrainian Helsinki Group began to emerge, we clearly decided that it should be supported. Ivan and I wrote an application of entry into the Group. In 1979 we went to the Carpathians, gathered in Luzhky and discussed our situation.

V.O.: Who was there?

O.V.Sokulska: Mykhailo Horyn, Olga Horyn, Zynoviy Krasivskyi, Ivan Sokulsky Yaroslav Lesiv, and, of course, Mariya Hel and I gathered in Luzhky. Petro Rozumnyi was late for the meeting. We gathered to whoop it up for the New Year in the Carpathians, in the mountains, in the forest. In this way we celebrated the new 1979. There was also Chornovil’s son, Taras looked like a little Chornovil, Taras and Oksana of Mykhailo Horyn. It’s a pity, Olena Antoniv failed to come. I remember how Yaroslav, Ivan, Zynoviy and we all went to the mountains. We stood on a small island rounded by a river. Everything was covered with deep snow, so we were crawling waist-deep in snow. We were dancing, we were singing… In fact, over there a new composition of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group was forming. Yaroslav and Ivan had already put in applications for admission. (The applications of Yaroslav Lesiv, Zynoviy Krasivskyi, Ivan Sokulsky for admission to the UHG were dated October 1979--V.O.). Then we decided that women… Yaroslav and Ivan and Mykhailo said, Well, Orysia, we may be arrested, and you have kids…”

After the meeting we went to Lviv, to Olena Antoniv, Chornovils wife. There was Petro Rozumnyi. This was our last celebration with friends. For after all these celebrations troubles began brewing. (P.Rozumnyi was arrested on 8.10.1979, Ya.Lesiv on 15.11.1979, Z.Krasivskyi on 12.03. 1980, I.Sokulskyi on 11.04.1980, M. Horyn on 11.03.1981.--V.O.). The massive problems. The harassment at work set in. Recently he worked as a guard in a vocational school. The officers carried out searches there, and then they conducted searches at his home. Now I want to tell about the last search. It was performed on April 11. It was the last search during Ivan’s arrest.

Mariyechka, so it was in 1980, wasn’t it?

M.I.Sokulska: In 1980 he was behind bars already.

O.V.Sokulska: He found himself behind bars later: on April 11, 1980. We lived very modestly, at the time we had not this couch we are sitting on with you, there was nothing of the kind. Marichka slept on a cot.

V.O.: When was Marichka born?

O.V.Sokulska: Marichka was born on October 29, 1975. She was not five years old yet. Mother was either weeding a potato plot on the dam or working in the kitchen garden, and suddenly she came running and began tapping at the window and then said, They are coming to search you!” They did not wait for us to open the door, they began to break in. So, they forced the door and smashed in.

We were getting ready for the search, but we were short of time to do everything: we managed to hide Ivan’s poetry, however there were heaps of materials and we did not make it. So we were sleeping, we had one more room there, this is our bedroom, bed, my mother is tapping at the window and says, Get up, they are about to search you”. Well, of course, I rushed, Marichka slept here, there was a cot, they broke in, there was a whole bunch of them, perhaps a dozen men. Suddenly I caught sight of a piece of paper with something scribbled on it, it just stuck out there. I grabbed that piece of paper…

V.O.: Did you do it in full view of everybody?

O.V.Sokulska: Right, in full view of everybody. They rushed at me, but there was no managing me: the woman was chewing a piece of paper. I chewed it and cast a glance at Ivan, Ivan was laughing, and I asked him: What I ate? He answered: My poetry. The day before they searched all people who knew Ivan. They seized Ivan’s pocketbook and used it to carry out searches to the East of the Carpathians. If I dont miss my guess, they searched about fifty-seven people.

They used all kinds of techniques from picking the wall to sticking the ground in the kitchen garden. But I must say, they behaved very tolerant and did not go beyond the limits. You know, I was overwhelmed with aggressive emotion when I saw that Marichka woke up, sat down and began to cry, while I tried to dress her on her bed… I had to reassure the child somehow. In the khata they turned everything upside down, but they behaved more or less decently.

V.O.: Was Ivan arrested the same day?

O.V.Sokulska: Ivan was arrested on April 11. They got Ivan in one car, got me in another, and brought us to the KGB. I remember it as if it were today: the grandmother led Marichka on the street and she stood there and waved until the car was out of sight. Paddy wagon… I got in that car and thought: Why did I get in? I sure was guilty of this and that. I thought, They may lock me up for good! They brought me there, gave me an official document and released.

It was already late: about eight hours, maybe nine. I returned home like to a burnt house: everything was scattered about, a sort of spiritual desert, feeling of emptiness.

Then our Chistopol drudgery set in… He was sent to the Tatar Autonomous Republic.

V.O.: Were you summoned for examination during this investigation?

O.V.Sokulska: I was a witness in the case of Ivan Sokulsky. What did it look like? I know nothing, I saw nothing.” During the interrogations I was reminded once and again that they may imprison me.

V.O.: Was it talked about you and Ivan or you instead of Ivan?

O.V.Sokulska: At first they talked about jailing me and not Ivan and then about jailing both of us.

What provoked the arrest of Ivan? At first they imprisoned Petro Rozumnyi. You know, in his case they fabricated a sort of domestic crime. Ivan was able to attend the trial of Petro Rozumnyi as it was a domestic crime. They somehow failed to pattern their behavior in due time and admitted him. And Ivan wrote an article (Mr. Vasyl, they have recently returned it to me and Ill scan it for you). This article “Material evidence: Stalin Troika at work.” This article about the trial of Petro Rozumnyi was typed on four pages. Ivan depicted the whole judicial process. They used this article to incriminate Ivan.

There was a time when I, so to speak, supported Hryhoriy Prykhodko, Ivan Sokulsky, Petro Rozumnyi, Yaroslav Lesiv and an Evangelical Baptists, who was kept in a psychiatric hospital, I mean Synhayivskyi. This support included subscription to periodicals and corresponding. I knew what it was about. I realized that it wasn’t me who they needed in the first place, but they needed to correspond, have connections with the world, information which prevented their total isolation.

V.O.: Stefaniya Petrash-Sichko had a similar destiny when at one and the same time her husband and two sons were jailed she struggled to cope with three jails and also to support Vasyl Striltsiv.

O.V.Sokulska: I also supported Yaroslav Lesiv who did his term in the zone for domestic criminals. Ivan, Petro Rozumnyi, whom I was not allowed to visit because he was not my relative, but when he did his term working at chemicals plant in Nikopol, in Zhovti Vody, I visited him. They did not allow me to see Hryhoriy Prykhodko, nevertheless I subscribed to newspapers and magazines. It was my life. Now I reread Ivan’s letter from completely different point of view, I read the letters of Yaroslav, of Mr. Petro Rozumnyi, when he was out there in the Zeleny Klyn. I then had the program: my every week was not a bowl of cherries I had to write three letters weekly to my husband, one letter weekly to write to my brother, to write something for Mr. Petro and Prykhodko as well.

It was my life, I did it, and I say this before God with a clear conscience. Finally, Ivan was condemned to five years imprisonment in Chistopol jail: we went through tough times. We used to go there with Marichka Marichka was five or six years old. Marichka, perhaps, remembers and recalls how we stayed in those Chistopol hotels. We put up at a hotel, but they tried to break the door of our room out, we lurked somewhere on the second or third floor and we were afraid to venture out of this hotel.

In Chistopol prison we communicated with him through the glass. Marichka recalls her first time coming there when she was still a child. She said, Mom, where have we come to? To the menagerie? Ivan, you know, wanting to somehow protect Mariyka against the reality, said: I work here at the menagerie, we have animals here and cages, we take care of animals. Such was the dialogue between them in their letters. Then Mary arrived and asked, Dad, wheres are the cells, and where are the animals? I want to see animals.”−“They are not domesticated yet, Mariyechka, they cannot freely go to people yet.

I always went with Mariyechka to see him. The mother went to Chistopol when they began to fabricate the third term for Ivan. I remember this day very clearly when I started writing a strongly-worded appeal to Gorbachev. I went out of my khata Marichka somehow pressed herself against me, hugged me and said, Mom, will you come back? Well, I told the child that I would definitely be back, but I told mother that I did not know whether I would be back.

I went to the Chistopol public prosecutors office, to the jail: it was all over and done with and they condemned Ivan to another term after five years in prison (3.04.1985--V.O.). Say anything you like, but it nothing but a provocation. I found lawyer Rybalko (I still remember his name) in the prosecutors office in Tatarstan. The Muscovites gave me the address… who was it who gave me it then?--Petro Starchyk. We used to stop at his apartment in Tyoply Stan District in Moscow. He gave me the address. He seemed to be a more or less normal lawyer. When the lawyer familiarized himself with all materials of the case, he said: Orysia Vasylivna, I do not want to take your money, because I will not be able to help you in this case. It is a frame-up in black and white. Anyway, he was a decent man.

Then I went to Naberezhnye Chelny, because the investigator was there. I failed to find the Investigator out. There is nothing unusual about it: you make frequent trips and find nobody, find no investigator. I went back to Kazan, in Kazan I went to the prosecutor, I had an appointment with the prosecutor. I came to the prosecutor and he said to me: Why don’t you write letters to your husband in Russian? I said, I am Ukrainian. The Ukrainian Republic is a part of the USSR, and I have the right under the Constitution to write in my native language.”−“I am also a Tatar, but I speak Russian. And I let fall: You are not good Tartar, because if you were good Tartar, you would speak your native tongue. Then high words about Ivan’s case followed, I descended the stairs from the fourth floor of the prosecutors office, went out and−it was just psychological pressure exerted by prosecution−there was an ambulance near the entrance and there stood strappers in white overalls, they opened the door and grabbed my hand. It seemed that they were about to lock me up. I thought nothing could be done in this situation. Well, they are here to lock me up, so let it be, however I should behave with dignity. A kind of inner response.

V.O.: Dignity is our last argument.

O.V.Sokulska: I was thinking: If they are to lock me up, let them do it. So I pushed away the orderly’s hand. I do not understand, said I. He gazed at me incomprehensibly… I then gave them the go-by: Comrades, Make way and let me pass. They had no order to apprehend me. I passed on. I went ten meters or so down the street, I became week in the knees and a thought haunted me: They may follow me. I looked back and saw ambulance parked there and orderlies stopped dead in their tracks. I have no idea whether it was an order or just a coincidence, but I do not think it was a pure accident.

It was the end of the line and I went home. Then mother went to Chistopol. Maybe mother did not tell you how she went to Chistopol and Ivan went hunger strike and he was transferred to Kazan where he underwent surgical operation.

V.O.: What was the diagnosis??

O.V.Sokulska: Hernia. I knew that they would not allow his mother to see him, but it was important that Ivan knew that people worried about him and wanted to see him. I think that it was very important for Ivan at this point because Ivan was in a crisis. When they fabricated the article Insight, his mother was not allowed to see him, and she returned home, and Ivan was sentenced to three more years of imprisonment, he was sent to the Urals.

After that for nine months there were no letters from him. Ivan was informed that his wife had deserted him, his daughter had deserted him, and they had left for the Carpathians. Many a man called me to tell that he did not want to write me because I had behaved myself in a wrong way. For nine months they played with this situation. Ivan had already been in the Perm Oblast, he had been sentenced to solitary confinement and coolers, and I still had no information. Only then Olga Stokotelna went to visit Mykola Horbal. She called me from Kyiv and said: Orysia, save Ivan, he is in a very difficult situation, they are finishing Ivan. then I wrote an application to General Secretary Gorbachev and started preparing for a hunger strike without limit. I understood that it should not be done in Dnipropetrovsk and I contacted Starchyk in Moscow. For five days at home I fasted and stood the test moreover I had to cook for a child and survived, therefore I thought I could endure five-day hunger strike there as well. I sent a cable (it was in 1986) and demand to be allowed to see Ivan. At first they answered that I was denied the appointment legally, and then I received the telegram that he had been illegally put in the cell. At the time they preplanned the meeting of Reagan with our human rights activists. I knew that Ivan was on the list, and began to act more openly and insistently. Then they allowed me to see him and informed that he was kept in a solitary confinement illegally. They recalled their resolution and allowed me to see him. Three of us were going to meet him: me, Marichka and his mother. This first visit ever, on April 26, on the day of explosion at Chornobyl.

V.O.: On that same day?

O.V.Sokulska: On that very day we went to see him and they permitted us to stay with him for three days in a row: on the 26th we were there, and on the 27th, 28th and 29th we stayed with him. On our way back, only in Moscow we learned that Chornobyl exploded.

V.O.: Did your meeting take place in Kuchino?

O.V.Sokulska: Yes, it did. Mr. Vasyl, from this meeting I smuggled a statement on five pages of cigarette paper. I will not dwell on how women carried those statements and how they were written. We were given a room, and a kitchenette, a sort of small room. For Marichka with his mother stayed in the room while we all night sat in the kitchenette with a gas stove and the gas was burning there. Ivan had already prepared some materials. I was able to smuggle an ampoule, with which one could write. We already had the experience to do it. I smuggled away a statement written on five pages of cigarette paper. They searched all of us performing gynecological examination as well, but I managed to carry the pages out. I arrived in Moscow. All radio stations broadcasted the statement. I sent my people back home from Moscow and told mother and Marichka saying goodbye to them, If I don’t follow you, then this will be the will of God. I asked mother to take my child with her. Petro Starchyk met me in Moscow and this statement was passed on to all channels: BBC, Voice of America, and Liberty all of them broadcasted the statement. The statement listed all names of butchers at the zone VS-389/36. I have preserved that statement written on scraps of cigarette paper maybe you need to copy it.

Of course, those statements drew a wide response. But Ivan’s situation was not alleviated, but on the contrary it aggravated: now they began putting him in solitary cells. Then we set off, so to speak, on the new round. Then Ivan assumed the political prisoner status. There were no visits permitted, but the letters came in regularly during this period, I must say. After the beginning of perestroika and talks with Reagan held in Moscow, the jailers did their best to deliver letters in time.

I was not allowed to meet Ivan, but all the same I went to see him, though he was punished for breach of order in solitary confinement. In fact, the breach of order is a broad concept: the prisoner might put on socks in a non-standard way, or fasten the wrong button, or get up at a wrong time. At the time Valia−Valentyna Stus−was going to her husband’s grave and Olia Stokotelna was going to see Mykola Horbal. And I also went to visit Ivan. At the time they started publishing Ukrayinskyi Visnyk Monthly in Lviv, and Pavlo Skochok representing Ukrayinskyi Visnyk Monthly had to go with us. Pavlo Skochok was apprehended in Kyiv and he was not allowed to board the plane.

It was a terrible period. It was a sort of tragedy of my soul, and not only mine I do think that Valentyna Stus and Olga Stokotelna felt in the same way. Desponded, I was going to see Ivan, though the visit was not permitted. But before that I sent round a lot of applications to all instances I knew at the time, and, despite the fact that Ivan had switched over to the status of political prisoner together with the guys and despite the fact that Reagan was on his way to Moscow, I was allowed to meet Ivan for thirty minutes.

V.O.: Where did it take place? In Vsekhsvyatskaya?

O.V.Sokulska: Usually I met him in a meeting room in his zone. Well, Vsekhsvyatskaya…

V.O.: On December 8, 1987 we were transferred from Kuchino to Vsekhsvyatskaya.

O.V.Sokulska: Right, in Vsekhsvyatskaya I was allowed to see him. Ivan was brought into the room… Our meeting took place in the information room, for the record. There was a coffee table and something else. I brought some food with me. Ivan told me: I will not eat, I am on the hunger strike, I cannot eat anything. We began talking with him…

Olia was allowed to see Horbal. Well, it is clear that Valentyna remained there on the grave, Olga Stokotelna went to see Horbal. At first I got a refusal and hopelessly sat in silence there, I already knew about refusal, but they loved such intrigues and suddenly permitted me to see Ivan.

V.O.: Thirty-minutes visit?

O.V.Sokulska: Right, thirty minutes, no more, but I realized that those 30 minutes were also not legal. In four or six weeks Reagan’s meeting with our human rights activists had to be held in Moscow. I told Ivan about it and the jailers cut time of our meeting. As Ivan could not eat because he was on hunger strike, I thought that I had nothing to lose. May it be ten or fifteen minutes… it was important for me to have a quick glimpse of Ivan, to see the way he felt, what his mood was. I told him with a farewell nod: “Ivan, hang on to your hat! I do not know whether it is a good idea to go on a hunger strike,” those were my words. He says, You have your perestroika there, while here they are slowly killing us one by one.”

This was my last meeting with him in Vsekhsvyatskaya. In Vsekhsvyatskaya I had two meetings: one lasted three days and another thirty minutes. Of course, Mr. Vasyl, when they allowed me a short visit, some officers pointed the finger of blame on me: this is the one that smuggled the statement. I was clearly identified and labeled.

V.O.: Did the first meeting take place in Kuchino during the Chornobyl disaster?

O.V.Sokulska: Right, in Kuchino.

V.O.: And the other one took place in Vsekhsvyatskaya? Do you remember the date? You say the dandelion blossomed?

O.V.Sokulska: Yes, it was spring. I do not remember the date, but I have notes, telegrams, I’ll handle it all later.

V.O.: This happened in May 1988, when Reagan was expected to meet with human rights activists. But was Ivan released soon after that?

O.V.Sokulska: Ivan was released in 1988, on the third of August. On the fifth August he had to come here. But he was included into the last party transported: there was Kandyba…

V.O.: No, Kandyba, Horbal and I were transported on 12 August. We were brought to the Perm jail and then one by one we were carried home by air. I was released on August 21 in Zhytomyr, Mykola Horbal on August 23 in Kyiv, and Ivan Kandyba as late as on September 9 in Lviv.

O.V.Sokulska: And Ivan was discharged on August 3. But we were already preparing an action at the time. The Ukrainian Culturological Club had been working already. Mr. Mykhailo Horyn, Vyacheslav Chornovil, Hryhoriy Prykhodko had been already at large. They, Oles Shevchenko and we had been preparing the first political rally in support of political prisoners. It was to be held at the General Post Office. But the day before a Colonel Honchar met Prykhodko and me it seems Prykhodko arrived in Kyiv before me.

V.O.: Honchar, oh yes.

O.V.Sokulska: He found me in Rusanivka Housing Area, I stopped at Oles Shevchenko’s apartment. Prykhodko and I were walking along the Rusanivka Canal. Honchar came up and said, Mrs. Sokulska, you’d rather forebear from rallying: your husband was released on August 3. I said, Where are the guarantees? He said: I pledge my word. I said: It’s next to nothing. Prykhodko and I were sitting on a bench Honchar said: And Mr. Hryhoriy can confirm. And Hryhoriy laughed, saying, Yeah, Mr. Potter, I know your ways. I said, I do not believe you.”−“Ms. Orysia, I beg you not to take any action we’ve been informed already that things are off to a good start Ivan Hryhorovych will be free before long. I said, will I believe you, when Ivan Hryhorovych is at home.

Of course, we went on with preparing our protests, we had met the day before, the hunger strike continued. Do you know what the upshot of our protests was? They drove us away without looking where. For example, they drove me beyond the bounds of Myronivka and dumped in the steppe. Only Mr. Mykhailo was put onboard the liner because he had a political meeting in a Baltic State. Vyacheslav Chornovil was on the phone, and all the rest were scattered any old way: Naboka was driven in one direction, Skachko in another, and I was taken to Myronivka and put off somewhere in the wooded steppe. It took a long time to gather us all once more.

V.O.: Do you remember the date of the accident?

O.V.Sokulska: I do not remember the exact date. It happened on the fourth or fifth of August. They scattered us helter-skelter.

Ivan was released, and then the creative process, public and political life gained strength. A number of organizations began emerging, including Prosvita, various NGOs, Ukrainian Helsinki , Rukh, Ukrainian Republican Party Ivan died being a member of the latter, and I remained in the party for a long time supporting its traditions. Our khata was at the hub of activity. There were a lot of devices working in these rooms here we were at the center of things. And then the disintegration set in somehow: the Ukrainian Republican Party and the Peoples Rukh came into being. And Ivan began cracking up. As it turned out later, Ivan survived three heart attacks, none of which had ever been registered. In 1990 we had the Ukrayinske Slovo newspaper. We picketed in support of the independence of Ukraine. And then Ivan was beaten. It happened on May 1 or 2, 1990.

V.O.: Where did it take place?

O.V.Sokulska: Near the General Post Office over there where you entered my office at the of Ukrainian Women, in front of those doors. They have made the door now, once there was Ukrayinske Slovo newspaper published by Prosvita.

The “Evening with Sokulsky” Event was in two or three days and he appeared in all his glory in dark glasses. It was his first poetic reading event in Dnipropetrovsk.

After his discharge, on a tight timetable from 1988 till his death in 1992 Ivan published nine issues of cultural and artistic almanac Porohy, prepared his first collection Determination of Freedom, and delivered speeches at various conferences and rallies. I think all of them will be included in a new book. I think it will contain all his speeches, journalism published in Porohy and remembrances of his contemporaries. Today I am editing the third book: selected correspondence, epistolary heritage, very valuable letters to his mother from the zone and to me. They are not simply letters as such to me and his mother but the philosophical treatises on language, cultural environment in our land and the ways of its development. These are very interesting documents and let the reader estimate them.

V.O.: Thank you.

DAUGHTER

V.O.: Now Marichka Sokulsky will be speaking. What is the official variant of your name? Maria?

M.I.Sokulska: Mariya. The memories of my childhood include my fathers arrest. That is, even now, when I recall my father, I think first thing of his arrest, about which my mother had already told you. There were many people in our khata and then they led my dad to the patrol wagon. The next time I saw my dad when I was 13 years old, that is nine years later.

V.O.: Really?

M.I.Sokulska: Of course, we went to met him, but those were galloping episodes. I was a little bit shocked by those through-the-glass meetings in Chistopol jail. I remember one occasion when the jailers allowed me to run to the other side and sit on daddys knees. After that some officers appeared and I was chucked out. It was a violation of instructions.

I was growing up and I cannot say that my father is associated with a certain period of my life. So, these were short-term visits when I saw him. When he came back, I really felt that he was my father, that he had returned, and that I really had father, because earlier I saw his letters only. It was quite different. The letters could not contain dialogs although he tried his best to make dialogues. One time he imagined me a little girl although I had grown up already, the other time it was vice versa.

V.O.: Stus also wrote something like this in a poem about his son: “You’re still a boy of five for me.”

M.I.Sokulska: By the way, in our case it was about the same, too I now reread his letters where he was surprised (the letter was in Russian): Why Marichka is not growing up? In my dreams she always appears as a little girl.” He wrote some letters in Russian so that they could reach addressee sooner. He wrote that I was ten years old, but he always dreamed that I was four or five. That mental vision failed to compensate for the lack of communication. So he remembered me like I was when he left me.

V.O.: How did your relationship form when he came back?

M.I.Sokulska: Well, basically, ok. Indeed, everything was fine. That is, it was not idyllic, because I was already a big girl. I suspect that maybe my father found in me something he was not ready to deal with. It was not necessarily anything bad, maybe just something different and something he did not expect to meet with. I think for him it was difficult as well because his daughter a big girl, whom he, in fact, knew little about. it could not happen otherwise under such conditions. So for both of us it was, by and large, so to speak, coming to know each other.

V.O.: I again appeal to Stus: when Stus returned, his Dmytro was already 14 years old. He said that it was very difficult to get accustomed to one another. That period lasted only nine months.

M.I.Sokulska: Well, in our case it was the same. He returned from the zone and had certain acquired habits doing such term a man cannot but fall into certain habits, some routine, and sort of ritual. He tried to recreate a home, may be unwittingly, his acquired frame of mind. I think that both we and he were exposed to difficulties because all conditions had changed drastically.

V.O.: I attended the presentation in Kyiv of the little book Letters to Mariyechka and took a picture. I have given it to Ivan’s mother and I will give you one as well, and I have one too, de bene esse to ensure against its loss. I wanted to photograph all of you together here. May you sit down, please…

Now we will look attentively at the photo. This is you, right? This is Ivan’s mother? These are works of Zalyvakha, right?

O.V.Sokulska: Yes, all of them were painted by Panas Zalyvakha. This is his early work it is, in principle, uncharacteristic for him, for he started like an avant-garde artist, perhaps. All these works are his, including that woodcarving, and those works over there are also his.

V.O.: And this one here was it also painted by Zalyvakha?

M.I.Sokulska: No, no, its our Dnipropetrovsk artist.

V.O.: No, it does not look like his picture. And that one was painted by Zalyvakha.

M.I.Sokulska: It was painted by Zalyvakha. The manner is his, except one detail, and I point to it at once, because it seems unusual for him, but if you take a closer look… There were these three friends Lesiv, Zalyvakha and Krasivskyi. And Sokulsky to add. I remember how they came together, when my father came back. Certainly, no one expected that that this event would be prophetic in some sense, that it would become a reality in a short-term. The man joked saying that life is short, of course when we die, guys, and come together in the kingdom of God and start dancing there the Lord Himself will dance to our rhythms… And soon they were all dead. Thank God, Zalyvakha is still here with us. For Krasivskyi, Lesiv and Sokulsky passed away soon (Z.Krasivskyi died 20.09.1991, Ya.Lesiv 10.10.1991, I.Sokulskyi 22.06.1992, P.Zalyvaha 23.04.2007.--V.O.). Often recollecting the tragedy of their deaths, I at the same time remember his intrepid, radiant and starry look and I begin to feel better.

V.O.: Recently we attended in Kyiv Mykhailo Soroka’s Evening Event observing his Ninety’s Anniversary. Many a speaker told about him as a subtle psychologist. Once a young insurgent from Kuban whom Soroka befriended was sentenced to death and it was a final sentence. And how did Soroka reassure him so that this guy would not be afraid of death? Its not that bad we all will be there and we will plant flowers, cultivate orchids, we will be watering them…

M.I.Sokulska: That is the continuation of earthly life, only more idyll one. Well, it may be a way out, when soothing a man, so to speak. I do not know for how long such words may tranquilize a man, but perhaps for a certain period ...

V.O.: Thank you. It was Marichka Sokulska, April 5, 2001.

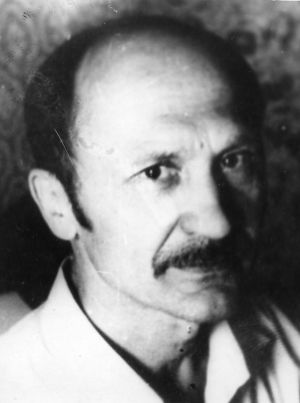

On the V.Ovsiyenko’s photos: Orysia Sokulska mother Nadiya Ivanivna Sokulska wife Orysia and daughter Marichka Sokulska, friend Serhiy Aliyev-Kovyka Kozak cross on the grave of I.Sokulskyi (author S.Aliyev-Kovyka) menhir near the grave of I.Sokulskyi S.Aliyev-Kovyka is standing nearby. Portrait of Ivan Sokulsky painted by Panas Zalyvakha. Two old photos of Ivan Sokulsky.

[1] The name of the historical territory of Ukraine, including central and northern its oblasts (translator’s note).

[2] Kulish or kulesha is a kind of Ukrainian field hot cereal (translator’s note).

[3] See also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menhir (translator’s note).

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuzhmash (translator’s note).