On September 18, artist Alla Horska would have turned 90. She left a significant mark on the history of the Ukrainian dissident movement, and her tragic death caused a considerable stir. Information about Horska’s death was tracked and recorded by the KGB, which systematically informed the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU), including its First Secretary Petro Shelest. Moreover, the case was under special control of the Prosecutor’s Office of the Ukrainian SSR.

Alla Horska was one of the driving forces behind the Ukrainian Sixtiers movement and the “Suchasnyk” (Contemporary) Club of Creative Youth in Kyiv. In her mature years, she became aware of her national identity: she learned the Ukrainian language and immersed herself with great dedication in the national and cultural revival of the 1960s. In particular, in a 1961 letter to her father, who was then head of the Odesa Film Studio, Alla Horska wrote: “You know, I always want to write in Ukrainian. You speak Ukrainian—and you start thinking in Ukrainian. I’m reading Kotsiubynsky. What a wonderful language…” At the same time, she lamented: “Memories press down with a terrible weight. Memories of the 1930s. My heart pounds horribly from the emotional pain. I want to do something, to run somewhere, to be indignant, to scream.”

In 1962, Alla Horska, along with Vasyl Symonenko and Les Tanyuk, discovered mass burial sites of NKVD victims in Bykivnia, near Kyiv. They wrote to the Kyiv City Council proposing the creation of a memorial. The Club of Creative Youth initiated an investigation. Les Tanyuk, Vasyl Symonenko, and Alla Horska began to gather information. But by 1963, pressure began to mount on them, and Vasyl Symonenko tragically died as a result of a police beating.

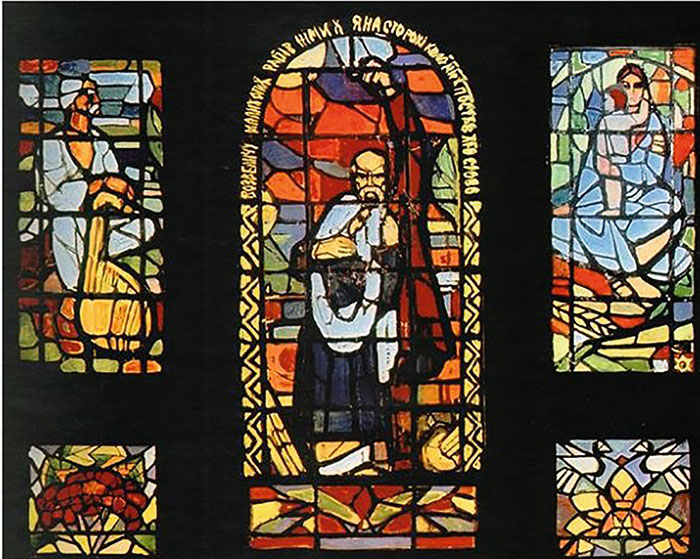

The “Stained Glass” Affair

In 1964, the destruction of a stained-glass window created for the 150th anniversary of Taras Shevchenko in the vestibule of Kyiv University, co-authored by Alla Horska, caused a major resonance. It depicted an angry Kobzar with a woman—a symbol of Mother Ukraine—clinging to him. Taras Shevchenko proclaimed the lines: “I will exalt these lowly, voiceless slaves! And I will place my word to stand on guard for them!” The stained glass was destroyed immediately after its completion as “a work deeply alien to the principles of socialist realism.” Sixtier Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska recalled: “The main vandal was the university rector, Shvets. He personally, without waiting for the commission’s conclusions, smashed the ideologically harmful stained-glass window… Why is Mother Ukraine so sad? What ‘judgment,’ what ‘punishment,’ and upon whom does Taras call? And in general, why is Ukraine behind bars?” According to a decision by the Bureau of the Kyiv Regional Board of the Union of Artists of Ukraine on April 13, 1964, it was determined: “The stained-glass window presents a grossly distorted, archaic image of T. H. Shevchenko in the style of a medieval icon, which has nothing in common with the image of the great revolutionary-democrat… The image of Kateryna in the sketch is rendered in the same icon-painting style, being nothing more than a stylized representation of the Mother of God… Shevchenko’s words, written in a Church Slavonic script (Cyrillic) in combination with the iconographically interpreted images, sound ideologically ambiguous. In the images of the stained-glass window, there is not the slightest attempt to show a Shevchenko of Soviet worldview. The images created by the artists deliberately lead into the distant past.”

Stained-glass window “Shevchenko. Mother.” A work by artists Halyna Sevruk, Alla Horska, Opanas Zalyvakha, Halyna Zubchenko, and Liudmyla Semykina, 1964

The authors of the stained glass were expelled from the Union of Artists of the UkrSSR for this work. Subsequently, the fate of some of them would be even more tragic: in 1965, the first wave of post-Stalinist repressions swept through Ukraine, and among its victims was the stained glass’s co-author and a close friend of Alla Horska, artist Opanas Zalyvakha. He was accused of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda and sentenced to five years in a strict-regime labor camp.

Carnations in Court

Alla Horska testified in the cases of Yaroslav Hevrych, Yevheniya Kuznetsova, Oleksandr Martynenko, and Ivan Rusyn, who were arrested for possessing Ukrainian literature banned in the USSR. When the defendants were brought to the Kyiv Regional Court for their hearing on March 25, 1966, they were surprised to be greeted with bouquets of carnations by Lina Kostenko, Alla Horska, Nadiya Svitlychna, and Ivan Dziuba.

On December 16, 1965, Horska openly accused law enforcement agencies of putting psychological pressure on the defendant Yaroslav Hevrych during interrogation, which caused him to give false testimony. Based on the then-current Constitution and laws, she cogently argued that reading a book, even one ideologically alien to the official doctrine, was not a crime. The persuasiveness of the artist’s words was disarming and infuriating. In 1967, with a group of Kyivans, she traveled to Lviv for the trial of Viacheslav Chornovil, where she signed a letter protesting the illegal conduct of the court. In 1968, Alla Horska, among 139 figures of science, literature, and art, signed a letter addressed to the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Leonid Brezhnev, the Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers Alexei Kosygin, and the Chairman of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet Nikolai Podgorny. The intellectuals stressed that “the political trials conducted in recent years are becoming a form of suppressing dissent, a form of suppressing civic activity and social criticism, which are necessary for the health of any society. They testify to the ever-stronger restoration of Stalinism. […] In Ukraine, where violations of democracy are complemented and exacerbated by distortions in the national question, the symptoms of Stalinism are even more pronounced.” The letter with signatures was delivered in April 1968, and by the end of April, the authorities began to pressure those who had signed it. Furthermore, in July 1968, along with the poet Lina Kostenko, critic Ivan Dziuba, publicist Yevhen Sverstiuk, and writer Viktor Nekrasov, Alla Horska wrote an open appeal to the newspaper “Literaturna Ukraina” in connection with a slanderous article about the “letter of 139” by the Soviet writer and KGB informant Oleksiy Poltoratsky. Later, at a meeting of the Union of Artists, when accusations were being leveled against those who had signed the protest letter, the general oppressive silence was broken by Alla Horska, who declared that all these accusations were lies and forced the text of the protest to be read aloud. The presidium of the meeting was compelled to comply with the artist’s demand. And when the protest was read, it became clear that the letter contained no hint of a state coup, only a polite demand for justice. For that speech, Alla Horska was expelled from the Union of Artists for a second time.

However, this did not stop the brave woman. In the winter of 1969, she visited Opanas Zalyvakha in the Mordovian concentration camp zone ZhKh-385. And on August 28, 1970, when he was released from prison, she actively participated in organizing a grand welcome for him at the Kyiv restaurant “Natalka.” That same year, 1970, the artist was summoned for interrogation in Ivano-Frankivsk for her support of Valentyn Moroz’s protests, but she refused to give any testimony.

The Mystery of Her Death

Alla Horska corresponded with political prisoners (systematically with the artist Opanas Zalyvakha), maintained relationships with their families, and provided them with moral and material assistance. Her home became a place where people returning from behind barbed wire would stay, and their relatives, loved ones, and acquaintances would gather. A circle of creative intellectuals rallied around the artist, listening to this courageous woman and considering her an authority. Horska was astonishingly brave, though she may have been aware of how seriously she was risking her life. She was watched, she was threatened, and listening devices aimed at her family’s apartment were installed in her neighbors’ home.

On November 28, 1970, Alla Horska went to her father-in-law’s home in Vasylkiv (Kyiv Oblast) to pick up a sewing machine and never returned. On December 2, 1970, her body was found in the cellar of her husband’s father’s house, Ivan Zaretsky. Initially, the murder case was handled by the prosecutor’s office of the Vasylkiv district. However, by December 7, it was decided to entrust the investigation to V. I. Viktorov, Deputy Head of the investigative department of the Kyiv Oblast prosecutor’s office and Counselor of Justice; H. E. Baumshtein, prosecutor-criminologist; and H. Y. Strashnyi, investigator of the Kyiv-Sviatoshyn district prosecutor’s office and a first-class lawyer. According to the conclusions of the forensic medical examination, “the death of A. O. Horska occurred from a multi-fragmentary fracture of the skull bones with hemorrhaging under the brain lining.” The cause of death, according to the examination, was “blows from a blunt object with a limited impact surface”—a hammer.

From the archives. A special report from the head of the KGB of the UkrSSR, Vitaliy Fedorchuk, to the Central Committee of the CPU of the UkrSSR, 1970

On the day her body was found, Alla Horska’s husband, Viktor Zaretsky, was arrested on suspicion of murdering his wife. During interrogations, he was subjected to psychological pressure, as a result of which he confirmed the official version that his father, Ivan Zaretsky, had reasons to kill his daughter-in-law. Consequently—in the resolution “On the conclusion of the criminal case on the charge against I. A. Zaretsky under Article 94 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR”—“based on the testimony of the Horskys’ neighbor and friend, H. K. Zabrodina, O. V. Horsky (A. Horska’s father), and letters from I. A. Zaretsky to his nephew K. I. Mytsmanenko in the city of Tambov,” it was asserted that the father-in-law, “harboring hostile feelings toward A. O. Horska, murdered her on 11/28/1970, after which he committed suicide on 11/29/1970.”

However, a number of doubts about the official version have been raised, mainly by people who knew the artist well. In particular, it was pointed out that an old, physically weak man like Ivan Zaretsky could not have overpowered a physically strong woman like Alla Horska, and “no traces of dragging, struggle, or self-defense were found on the body or clothing of the deceased.” Friends, relatives of the deceased, and some researchers expressed the opinion that the artist’s death was the work of a “political assassinations department” subordinate to the USSR leadership.

The Case Is Not Closed

The resonance caused by Alla Horska’s death greatly concerned the authorities. As early as December 3, 1970, a special message signed by the head of the KGB of the UkrSSR, Vitaliy Fedorchuk, was sent to the Central Committee of the CPU: “Since A. O. Horska is known as an authoritative figure among nationalist-minded elements, it is not excluded that they may use her funeral for provocative purposes. We are taking operational measures to prevent possible undesirable actions on the part of these individuals.” It is noteworthy that this special message bore a handwritten resolution from the head of the KGB of the UkrSSR, Vitaliy Fedorchuk: “Comrade P. Y. Shelest was informed on December 4, 1970.” Furthermore, a “Secret Message” from the KGB of the UkrSSR to the Central Committee of the CPU dated December 5, 1970, emphasized: “According to data sent to the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR, nationalist-minded individuals are attempting to use the funeral of Alla Horska for purposes undesirable to us. Due to the fact that the funeral has been postponed to December 7, provocative assumptions and fabrications are being spread: an employee of the ‘Mystetstvo’ publishing house, Korohodsky, stated that this is a deliberate delay. The KGB does not want the funeral to take place on Constitution Day, lest it take on the character of a political demonstration. Certain individuals proposed to protest to the prosecutor’s office and the city council, demanding the release of the body. As a result of the measures we have taken, their intention did not find broad support.” Ivan Franko’s granddaughter, Zynoviia, had arranged for Alla Horska’s burial at the centrally located Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv on December 4, but the funeral was postponed to December 7 at the suburban Berkovetske Cemetery. The farewell to the artist took place in her studio on Filatova Street. That day, several hundred people gathered to pay their respects.

In a report signed by the head of the KGB of the UkrSSR, Vitaliy Fedorchuk, to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine dated December 11, 1970, it was mentioned: “The mysterious circumstances and causes of the murder were discussed in speeches during the funeral… In this regard, we would consider it expedient to instruct the prosecutor who handled this case to interrogate Serhienko and Hel in order to stop the spread of provocative rumors in connection with Horska’s murder.” It was also mentioned that “evaluating the version of I. A. Zaretsky’s involvement in Horska’s murder, the poet Lina Kostenko expressed herself as follows: ‘This is all too vile to be plausible.’”

Even after Alla Horska’s funeral, on December 18, 1970, a special message signed by the head of the KGB of the UkrSSR, Vitaliy Fedorchuk, was sent to the Central Committee of the CPU: “According to data sent to the Committee for State Security under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR, Olena Antoniv, the wife of Viacheslav Chornovil, who is known to the KGB for his nationalist sentiments and is a resident of Lviv, is commenting on the death of the artist Horska among her circle, spreading provocative rumors that the state security agencies now want to eliminate those among the creative intelligentsia whom they failed to get in the ‘60s. According to Antoniv’s assertion, such actions are to be carried out before the start of the XXIV Congress of the CPSU. According to her, this became known in Ukraine from Muscovites, but she did not name any specific individuals. Antoniv and her acquaintances are concerned for their future fate. The KGB under the Council of Ministers of the UkrSSR is taking measures to identify the sources of these provocative rumors.”

The artist’s son, Oleksiy Zaretsky, believed that the purpose of the crime was to intimidate, discredit, and demoralize the Ukrainian human rights movement, as well as to eliminate a person who provided significant support to her circle of like-minded people. It is also likely that further repressions were already being planned—the “great pogrom” of 1972. The case of Alla Horska was closed and, despite numerous appeals to the prosecutor’s offices of the UkrSSR, the USSR, and independent Ukraine, it remains not fully clarified to this day…

Liudmyla Semykina, a colleague of Alla Horska, a master of decorative arts, painter, Sixtier, and one of the organizers of the “Suchasnyk” Club of Creative Youth. A member of the Union of Artists of Ukraine (since 1957; expelled twice, reinstated in 1988)

Liudmyla Semykina, a colleague of Alla Horska, a master of decorative arts, painter, Sixtier, and one of the organizers of the “Suchasnyk” Club of Creative Youth. A member of the Union of Artists of Ukraine (since 1957; expelled twice, reinstated in 1988)

We were romantics, not realists. Alla Horska called me a sister-in-spirit, and when she talked with friends, she would put a hand on their shoulder. I watched her as an artist: her hands, how she stood, how she held her head. Alla was very beautiful, brilliantly educated, and intelligent. She walked proudly; she never made a single move without meaning. Alla loved art, and then herself in art, and she rejoiced for people who achieved something in art. She was poetic, philosophical in essence, and the national revival deeply touched her heart and became the meaning of her life. She was completely at ease with everyday life. Alla Horska was born for protest; she was a defender, a torch. She consciously made a sacrifice and was never afraid to speak the truth. I was frightened by her courage; I understood the danger. She was valiant, brave, and they feared her. She could break any political trial. That’s why they put her on a “blacklist” and later removed her. An assassin followed her; he studied his victim. She was lured into a trap. There is a version, recounted by Les Tanyuk, that I was supposed to travel with Alla in the car that was to bring that sewing machine from Vasylkiv. But at that time, I was working as a costume designer on the film “Zakhar Berkut.”

Serhiy Bilokin, Doctor of Historical Sciences:

Serhiy Bilokin, Doctor of Historical Sciences:

“Historians of 20th-century Ukrainian culture cannot bypass the mighty figures of Vasyl Stus and Alla Horska. Both of them perished. The archives of the Security Service of Ukraine hold documents with the signatures of such destroyers as Vitaliy Fedorchuk. It is all so simple, so unambiguous.”